Submitted:

16 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Bovine tuberculosis (bTB) is a zoonotic infectious disease and a chronic wasting illness. However, detecting and eradicating bTB remains a significant challenge in South Korea. This study evalu-ated the efficacy of a modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol for de-tecting bTB in cattle. The protocol included two ELISA tests: one performed on the day of puri-fied protein derivative (PPD) inoculation and another seven days post-inoculation. Results showed a significant increase in ELISA detection rates, from 11% to 76%, particularly in cattle that tested positive for the tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) assays (p < 0.0001). Notably, some cattle that were negative or had doubtful results in TST and IFN-γ as-says transitioned to ELISA-positive post-PPD inoculation. Additionally, some cattle identified as positive only by ELISA (S/P value ≥ 0.3) were confirmed to have bTB through gross examination or real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR). The proposed protocol was validated in bTB outbreak farms using S/P thresholds of 0.3 (PPD day) and 0.5 (seven days post-PPD), enabling the detection of infected cattle missed by TST and IFN-γ assays. Implement-ing this approach successfully eradicated bTB in outbreak farms with minimal culling. These findings highlight the potential of incorporating sequential ELISA tests to enhance bTB detection and support eradication efforts.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diagnostic Procedures Section

2.1.1. Tuberculin Skin Test (TST)

2.1.2. Interferon-Gamma Assay ( IFN-γ)

2.1.3. ELISA

2.1.4. Tissue Sample Collection & rRT- PCR(Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction)

2.1.5. Statistical Analyses

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Surveillance Period and Target Farms

2.2.2. Selection of the ELISA-Only Positive Cattle in a bTB Outbreak Farm and PCR Confirmation

2.2.3. Change of the ELISA Results 7 Days After PPD in TST and/or IFN-γ Positive Cattle

2.2.4. Changes in the ELISA Antibody Level 7 Days After PPD Inoculation in the Cattle Which Were All Negative for TST, IFN-γ Assay, and ELISA

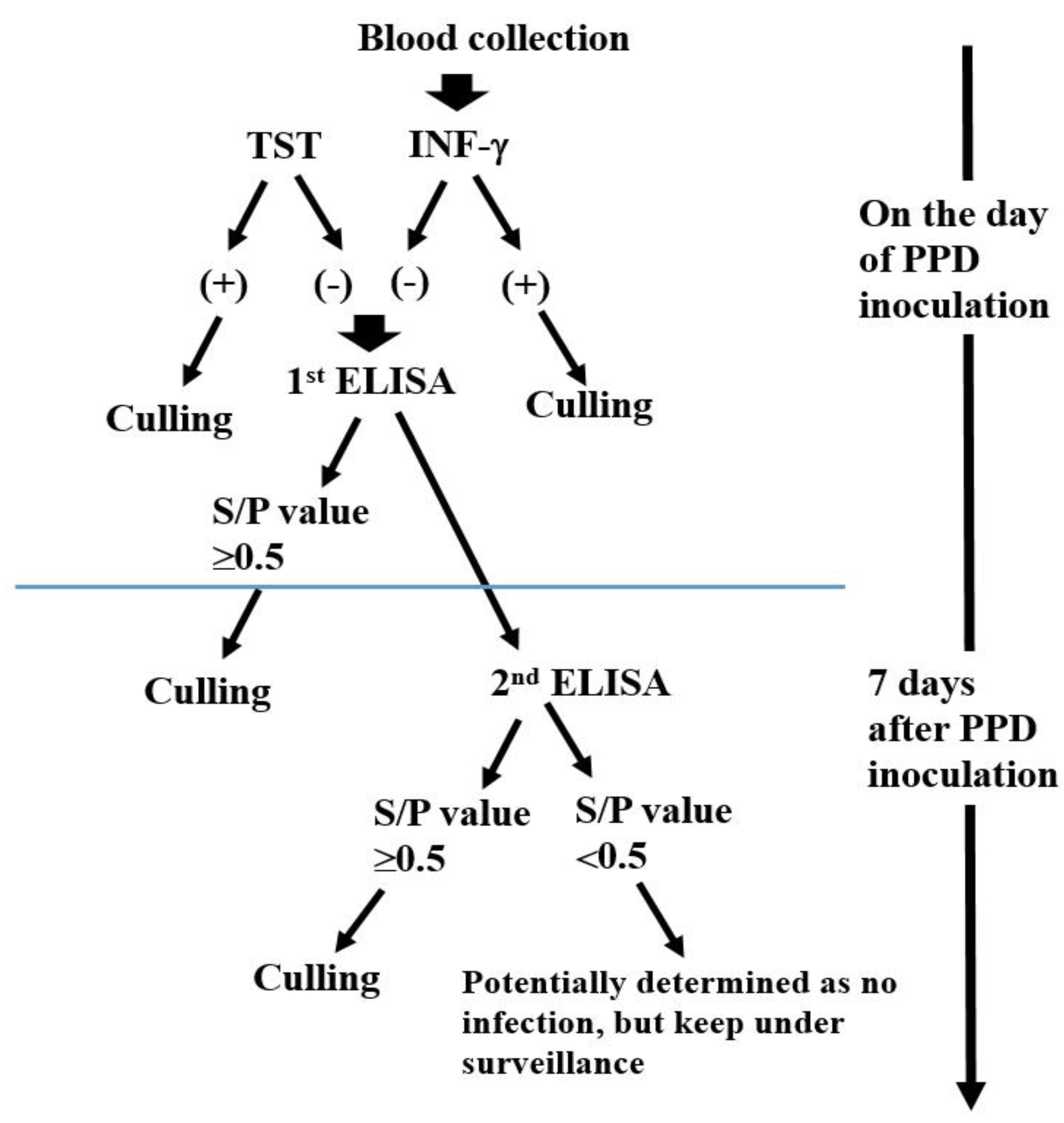

2.2.5. Application of ELISA for Eradication of bTB in the Chronic Outbreak Farms

Results

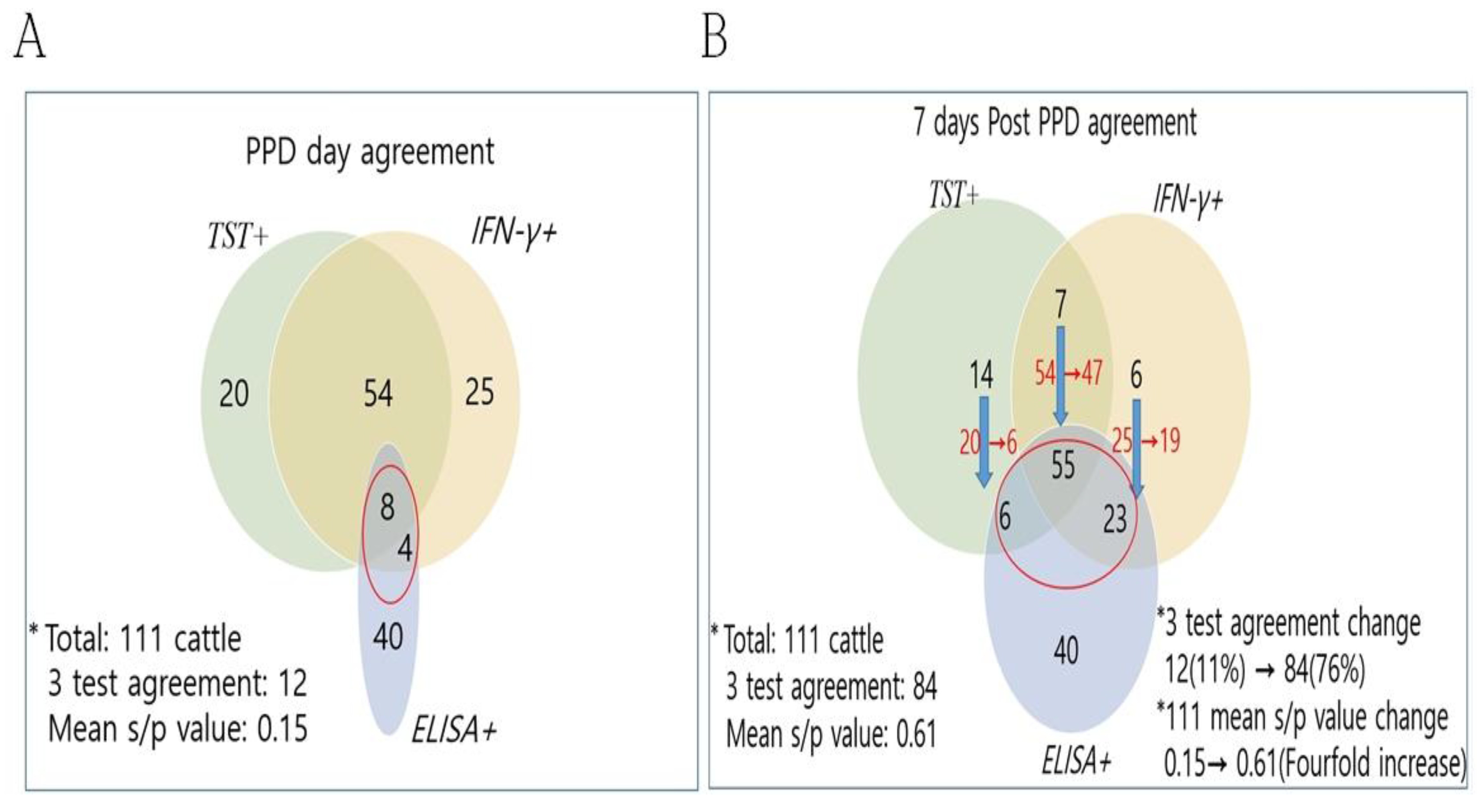

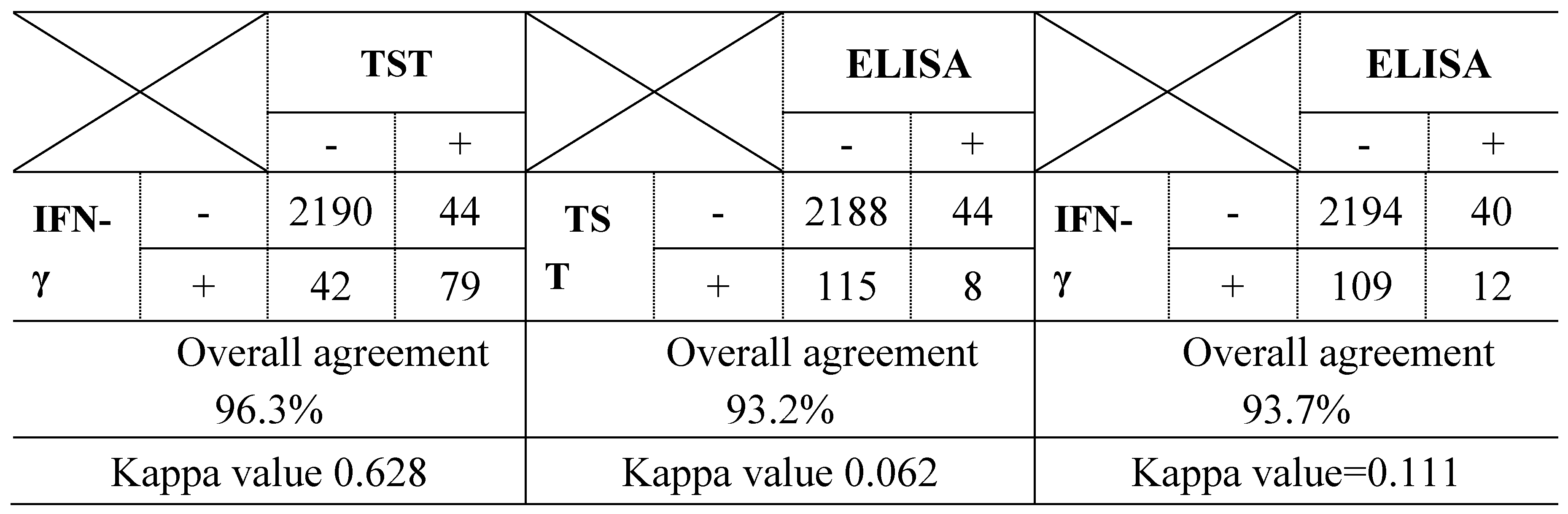

3.1. Detection Rate and Agreement of 3 Diagnostic Methods in 32 bTB Outbreak Farms

3.2. The ELISA -Only Positive 12 Cattle in bTB Chronic Outbreak Farms

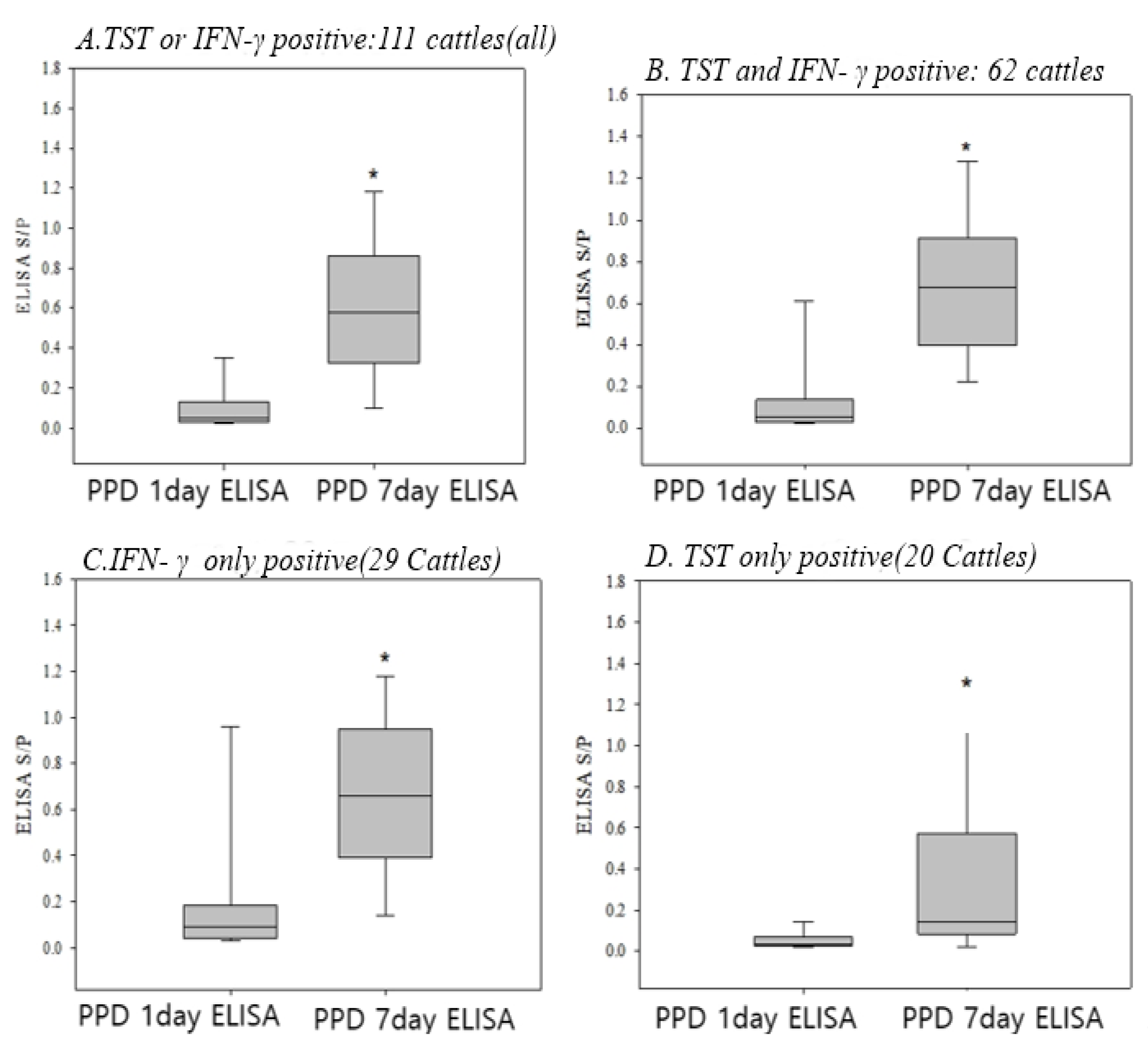

3.3. Change of the ELISA Results 7 Days After PPD in the TST and/or IFN-γ Positive Cattle

3.4. Conversion to Positive in the ELISA Results 7 Days After PPD in All Negative Cattle for TST, IFN-γ, and ELISA

3.5. Eradication of bTB in the Outbreak Farms Using the ELISA Test 7 Days After PPD Inoculation

3. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pollock, J.M.; Neill, S.D. Pollock, J.M.; Neill, S.D. Mycobacterium bovis infection and tuberculosis in cattle. Vet. J. 2002, 163(2), 115-127. [CrossRef]

- World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). Bovine tuberculosis. OIE Terrestrial Manual 2018, Chapter 3.4.6.

- Jang, Y.H.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, T.W.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, Y.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, E.J.; Yoon, S.S. Jang, Y.H.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, T.W.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, Y.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, E.J.; Yoon, S.S. Research on risk factors for transmission and bio-security measures associated with bovine tuberculosis breakdowns. QIA Research. 2019, 1442–1485.

- Waters, W.R.; Buddle, B.M.; Vordermeier, H.M.; Gormley, E.; Palmer, M.V.; Thacker, T.C.; Bannantine, J.P.; Stabel, J.R.; Linscott, R.; Martel, E.; Milian, F.; Foshaug, W.; Lawrence, J.C. Waters, W.R.; Buddle, B.M.; Vordermeier, H.M.; Gormley, E.; Palmer, M.V.; Thacker, T.C.; Bannantine, J.P.; Stabel, J.R.; Linscott, R.; Martel, E.; Milian, F.; Foshaug, W.; Lawrence, J.C. Development and evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for use in the detection of bovine tuberculosis in cattle. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18(11), 1882-1888. [CrossRef]

- Plackett, P.; Ripper, J.; Corner, L.A.; Small, K.; de Witte, K.; Melville, L.; Hides, S.; Wood, P.R. Plackett, P.; Ripper, J.; Corner, L.A.; Small, K.; de Witte, K.; Melville, L.; Hides, S.; Wood, P.R. An ELISA for the detection of anergic tuberculous cattle. Aust Vet J. 1989, 66(1), 15-19.

- Welsh, M.D.; Cunningham, R.T.; Corbett, D.M.; Girvin, R.M.; McNair, J.; Skuce, R.A.; Bryson, D.G.; Pollock, J.M. Welsh, M.D.; Cunningham, R.T.; Corbett, D.M.; Girvin, R.M.; McNair, J.; Skuce, R.A.; Bryson, D.G.; Pollock, J.M. Influence of pathological progression on the balance between cellular and humoral immune responses in bovine tuberculosis. Immunology 2005, 114, 101–111. [CrossRef]

- Koni, A.; Juma, A.; Morini, M.; Nardelli, S.; Connor, R.; Koleci, X. Koni, A.; Juma, A.; Morini, M.; Nardelli, S.; Connor, R.; Koleci, X. Assessment of an ELISA method to support surveillance of bovine tuberculosis in Albania. Ir. Vet. J. 2016, 69, 11. [CrossRef]

- Choi KY, Choi ES. A comparison study of tuberculin, IFN-γ, and antibody ELISA assay for the diagnosis of bovintuberculosis. Graduation Thesis, College of Veterinary Medicine, Chonbuk National University.2014. http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T13576874&outLink=K.

- Jeong C, Yun GR, Ra DK, Kim KM, Lee JG, Kim KH, Lee SM. 2014. Case of bovine tuberculosis diagnosis in a slaugterhouse confirmed as PPD negative. Korean J Vet Serv, 2014, 37(2), 131-136 ISSN 1225-6552, eISSN 2287-7630. [CrossRef]

- Harboe, M.; Wiker, H.G.; Duncan, J.R.; Garcia, M.M.; Dukes, T.W.; Brooks, B.W.; Turcotte, C.; Nagai, S. Harboe, M.; Wiker, H.G.; Duncan, J.R.; Garcia, M.M.; Dukes, T.W.; Brooks, B.W.; Turcotte, C.; Nagai, S. Protein G-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for anti-MPB70 antibodies in bovine tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 913–921. [CrossRef]

- Harboe, M.; Nagai, S.; Wiker, H.G.; Sletten, K.; Haga, S. Harboe, M.; Nagai, S.; Wiker, H.G.; Sletten, K.; Haga, S. Homology between the MPB70 and MPB83 proteins of Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Scand. J. Immunol. 1995, 42, 46–51. [CrossRef]

- Lyashchenko, K.; Whelan, A.O.; Greenwald, R.; Pollock, J.M.; Andersen, P.; Hewinson, R.G.; Vordermeier, H.M. Lyashchenko, K.; Whelan, A.O.; Greenwald, R.; Pollock, J.M.; Andersen, P.; Hewinson, R.G.; Vordermeier, H.M. Association of tuberculin-boosted antibody responses with pathology and cell-mediated immunity in cattle vaccinated with Mycobacterium bovis BCG and infected with M. bovis. Infect.Immun. 2004, 72, 2462–2467. [CrossRef]

- Waters, W.R.; Palmer, M.V.; Stafne, M.R.; Bass, K.E.; Maggioli, M.F.; Thacker, T.C.; Linscott, R.; Lawrence, J.C.; Nelson, J.T.; Esfandiari, J.; Greenwald, R.; Lyashchenko, K.P. Waters, W.R.; Palmer, M.V.; Stafne, M.R.; Bass, K.E.; Maggioli, M.F.; Thacker, T.C.; Linscott, R.; Lawrence, J.C.; Nelson, J.T.; Esfandiari, J.; Greenwald, R.; Lyashchenko, K.P. Effects of serial skin testing with purified protein derivative on the level and quality of antibodies to complex and defined antigens in Mycobacterium bovis-infected cattle. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2015, 22, 641–649. [CrossRef]

- Palmer MV, Waters WR, Thacker TC, et al. 2006. Effects of different tuberculin skin-testing regimens on gamma interferon and antibody responses in cattle experimentally infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 13(3):377–384.

- Silva, E. Silva, E. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in the diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 2001, 78, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- de la Rua-Domenech, R.; Goodchild, A.T.; Vordermeier, H.M.; Hewinson, R.G.; Christiansen, K.H.; Clifton-Hadley, R.S. de la Rua-Domenech, R.; Goodchild, A.T.; Vordermeier, H.M.; Hewinson, R.G.; Christiansen, K.H.; Clifton-Hadley, R.S. Ante mortem diagnosis of tuberculosis in cattle: a review of the tuberculin tests, gamma-interferon assay and other ancillary diagnostic techniques. Res. Vet. Sci. 2006, 81, 190–210. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.S. Lee, J.J.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.S. A Comparative Study on the Diagnosis of ELISA Test and PPD Test of the Bovine Tuberculosis. Korean J. Vet. Serv. 2010, 33, 335–340.

- Jang, Y.H.; Kim, T.W.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, Y.J.; Ryoo, S.; Park, C.H.; Kang, S.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Yoon, S.S.; Kim, J.M. Jang, Y.H.; Kim, T.W.; Jeong, M.K.; Seo, Y.J.; Ryoo, S.; Park, C.H.; Kang, S.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Yoon, S.S.; Kim, J.M. Introduction and application of the interferon-γ assay in the national bovine tuberculosis control program in South Korea. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 222. [CrossRef]

- Klepp, L.I.; Blanco, F.C.; Bigi, M.M.; Vázquez, C.L.; García, E.A.; Sabio y García, J.; Bigi, F. Klepp, L.I.; Blanco, F.C.; Bigi, M.M.; Vázquez, C.L.; García, E.A.; Sabio y García, J.; Bigi, F. B Cell and Antibody Responses in Bovine Tuberculosis. Antibodies 2024, 13, 84. [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, A.V.; Clifton-Hadley, R.S. Goodchild, A.V.; Clifton-Hadley, R.S. Cattle-to-cattle transmission of Mycobacterium bovis. Tuberculosis. 2001, 81, 23–41. [CrossRef]

- Chu, G.S.; et al. Chu, G.S.; et al. Epidemiological study on bovine tuberculosis outbreaks in endemic areas. Korean J. Vet. Serv. 2009, 32, 119–124.

- Chai, J.; Wang, Q.; Qin, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Shahid, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, W. Chai, J.; Wang, Q.; Qin, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Shahid, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, W. Association of NOS2A gen polymorphisms with susceptibility to bovine tuberculosis in Chinese Holstein cattle. PLoS One 2021, 16(6), e0253339. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Gandham, S.; Rana, A.; Maity, H.K.; Sarkar, U.; Dey, B. Kumar, R.; Gandham, S.; Rana, A.; Maity, H.K.; Sarkar, U.; Dey, B. Divergent proinflammatory immune responses associated with the differential susceptibility of cattle breeds to tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1199092. [CrossRef]

- Raphaka, K.; Matika, O.; Sánchez-Molano, E.; Mrode, R.; Coffey, M.P.; Riggio, V.; Glass, E.J.; Woolliams, J.A.; Bishop, S.C.; Banos, G. Raphaka, K.; Matika, O.; Sánchez-Molano, E.; Mrode, R.; Coffey, M.P.; Riggio, V.; Glass, E.J.; Woolliams, J.A.; Bishop, S.C.; Banos, G. Genomic regions underlying susceptibility to bovine tuberculosis in Holstein-Friesian cattle. BMC Genet. 2017, 18(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Schiller, I.; Oesch, B.; Vordermeier, H.M.; Palmer, M.V.; Harris, B.N.; Orloski, K.A.; Buddle, B.M.; Thacker, T.C.; Lyashchenko, K.P.; Waters, W.R. Schiller, I.; Oesch, B.; Vordermeier, H.M.; Palmer, M.V.; Harris, B.N.; Orloski, K.A.; Buddle, B.M.; Thacker, T.C.; Lyashchenko, K.P.; Waters, W.R. Bovine tuberculosis: A review of current and emerging diagnostic techniques in view of their relevance for disease control and eradication. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2010, 57, 205–220. [CrossRef]

| Group | Positivity for bovine tuberculosis | No. of cattle (%) | No. of positive cattle for each method (detection rate, %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST | IFN-γ | ELISA | TST | IFN-γ | ELISA | ||

| Negative | - | - | - | 2150(91.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TST only | + | - | - | 44(1.9) | 44 | 0 | 0 |

| IFN-γ only | - | + | - | 38(1.6) | 0 | 38 | 0 |

| ELISA only | - | - | + | 40(1.7) | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| TST & IFN-γ | + | + | - | 79(3.4) | 79 | 79 | - |

| TST & ELISA | + | - | + | 8(0.3) | 8 | - | 8 |

| IFN-γ & ELISA | - | + | + | 12(0.5) | - | 12 | 12 |

| TST& IFN-γ& ELISA | + | + | + | 8(0.3) | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Total positivity | 205(8.7)* | 2355(100)* | 123(5.2)* | 121(5.1)* | 52(2.2)* | ||

|

| Animal ID | TST | IFN-γ | ELISA* | Range of the ELISA S/P values | ELISA Mean S/P value | rRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | - | - | + | 0.68~1.62 | 1.17 | + |

| H12 | - | - | + | 0.81~1.12 | 1.04 | + |

| H5 | - | - | + | 0.53~1.27 | 0.95 | + |

| H39 | - | - | + | 0.67~1.12 | 0.91 | + |

| H20 | - | - | + | 0.74~0.98 | 0.88 | + |

| H14 | - | - | + | 0.33~0.81 | 0.61 | + |

| H1 | - | - | + | 0.49~0.70 | 0.60 | + |

| H9 | - | - | + | 0.32~0.68 | 0.55 | + |

| H38 | - | - | + | 0.35~0.71 | 0.54 | + |

| H17 | - | - | ± | 0.36~0.67 | 0.42 | + |

| H22 | - | - | ± | 0.31~0.66 | 0.41 | + |

| H54 | - | - | ± | 0.3~0.74 | 0.39 | + |

| Total | - | - | 12 | 0.3~1.62 | 0.71 | 12 positive |

| Farm ID | Positive cattle Age | TST result | IFN-γ result | ELISA S/P value (PPD inoculation day) | ELISA S/P value (7 days after PPD) | rRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J○○ | 89 month | - | - | 0.47 | 1.11(+) | + |

| L○○ | 48 month | - | - | 0.36 | 1.21(+) | + |

| L○○ | 15 month | - | - | 0.49 | 0.77(+) | + |

| Y○○ | 35 month | - | - | 0.29 | 0.51(+) | + |

| U○○ | 69 month | - | - | 0.02 | 1.33(+) | + |

| U○○ | 65 month | - | - | 0.01 | 0.67(+) | + |

| K○○ | 54 month | - | - | 0.03 | 0.97(+) | + |

| Study period | Area | Farm ID | Breed | Herd size | No. of bTB-cattle | Application protocol | No. of bTB recurrences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~2013.11 | HS-1 | U** | Hanwoo | 71 | 38 | TST only confirm (ELISA monitoring) |

8 |

| P** | 69 | 18 | 5 | ||||

| 2013.12 ~ 2015. 11 |

HC | J* | 74 | 3 | 3 | ||

| HC | J* | 16 | 7 | Simultaneous 3 Test TST, IFN-γ, ELISA (7days post-PPD) |

4 | ||

| J** | 34 | 22 | 4 | ||||

| HS-2 | S** | Dairy cow | 42 | 8 | 4 | ||

| SUM | 306 | 96 | MEAN | 4.7 | |||

| 2015.12 ~ 2017. 06 |

HC | J** | Hanwoo | 124 | 8 | Simultaneous 3 Test TST, IFN-γ, ELISA (7days post-PPD) |

2 |

| HS-2 | B** | 75 | 6 | 1 | |||

| Y** | 66 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| U** | 157 | 19 | 2 | ||||

| HS-3 | L** | 142 | 43 | 2 | |||

| HS-4 | K** | 47 | 34 | 2 | |||

| SUM | 611 | 114 | MEAN | 1.7 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).