Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Area

2.2. Satellite Data

2.3. In-Situ Measurements

2.4. Electromagnetic Models

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Furtak, K., & Wolińska, A. (2023). The impact of extreme weather events as a consequence of climate change on the soil moisture and on the quality of the soil environment and agriculture–A review. Catena, 231, 107378. [CrossRef]

- Donati, I. I. M., Viaggi, D., Srdjevic, Z., Srdjevic, B., Di Fonzo, A., Del Giudice, T., Cimino, O., Martelli, A., Dalla Marta, A., Henke, R., & Altobelli, F. (2023). An analysis of preference weights and setting priorities by irrigation advisory services users based on the analytic hierarchy process. Agriculture, 13(8), 1545. [CrossRef]

- Della Rocca, F., De Feis, I., Masiello, G., Pasquariello, P., & Serio, C. (2023, October). Comparison of the IASI water deficit index and other vegetation indices: the case study of the intense 2022 drought over the Po Valley. In Remote Sensing of Clouds and the Atmosphere XXVIII (Vol. 12730, pp. 94-107). SPIE.

- Farooq, A., Farooq, N., Akbar, H., Hassan, Z. U., & Gheewala, S. H. (2023). A critical review of climate change impact at a global scale on cereal crop production. Agronomy, 13(1), 162. [CrossRef]

- Ramat, G., Santi, E., Paloscia, S., Fontanelli, G., Pettinato, S., Santurri, L., Souissi, N., Da Ponte, E., Abdel Wahab, M.M., Khalil, A.A., Essa Y.H., Ouessar, M., Dhaou, H., Sghaier, A., Kassouk, Z. & Lili Chabaane, Z. (2023). Remote sensing techniques for water management and climate change monitoring in drought areas: case studies in Egypt and Tunisia. European Journal of Remote Sensing, 56(1), 2157335. [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2023. FAO publications catalogue 2023. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Tian, J., Zhang, Z., Philpot, W. D., Tian, Q., Zhan, W., Xi, Y., Wang, Y & Zhu, C. (2023). Simultaneous estimation of fractional cover of photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic vegetation using visible-near infrared satellite imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment, 290, 113549. [CrossRef]

- Thenkabail, P. S., Smith, R. B., & De Pauw, E. (2000). Hyperspectral vegetation indices and their relationships with agricultural crop characteristics. Remote sensing of Environment, 71(2), 158-182.

- Harries, J., Carli, B., Rizzi, R., Serio, C., Mlynczak, M., Palchetti, L., ì.Maestri, T., Brindley, H., & Masiello, G. (2008). The far-infrared Earth. Reviews of Geophysics, 46(4).

- Wolanin, A., Camps-Valls, G., Gómez-Chova, L., Mateo-García, G., van der Tol, C., Zhang, Y., & Guanter, L. (2019). Estimating crop primary productivity with Sentinel-2 and Landsat 8 using machine learning methods trained with radiative transfer simulations. Remote sensing of environment, 225, 441-457. [CrossRef]

- Murino, L., Amato, U., Carfora, M. F., Antoniadis, A., Huang, B., Menzel, W. P., & Serio, C. (2014). Cloud detection of MODIS multispectral images. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 31(2), 347-365. [CrossRef]

- Paloscia, S., Santi, E., Fontanelli, G., Montomoli, F., Brogioni, M., Macelloni, G., Pampaloni, P., & Pettinato, S. (2014). The sensitivity of COSMO-SkyMed backscatter to agricultural crop type and vegetation parameters. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 7(7), 2856-2868. [CrossRef]

- Santi, E., Paloscia, S., Pettinato, S., Fontanelli, G., Mura, M., Zolli, C., Maselli, F.,Chiesi, M., Bottai, L., & Chirici, G. (2017). The potential of multifrequency SAR images for estimating forest biomass in Mediterranean areas. Remote Sensing of Environment, 200, 63-73. [CrossRef]

- Macelloni, G., Paloscia, S., Pampaloni, P., Marliani, F., & Gai, M. (2001). The relationship between the backscattering coefficient and the biomass of narrow and broad leaf crops. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 39(4), 873-884. [CrossRef]

- Paloscia, S., Pettinato, S., Santi, E., Notarnicola, C., Pasolli, L., & Reppucci, A. J. R. S. O. E. (2013). Soil moisture mapping using Sentinel-1 images: Algorithm and preliminary validation. Remote Sensing of Environment, 134, 234-248. [CrossRef]

- Khati, U., Lavalle, M., & Singh, G. (2021). The role of time-series L-band SAR and GEDI in mapping sub-tropical above-ground biomass. Frontiers in Earth Science, 9, 752254. [CrossRef]

- Hensley, S., Van Zyl, J., Lavalle, M., Neumann, M., Michel, T., Muellerschoen, R., Pinto N., Simard, M., & Moghaddam, M. (2015, October). L-band and P-band studies of vegetation at JPL. In 2015 IEEE Radar Conference (pp. 516-520). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Potin, P., Rosich, B., Grimont, P., Miranda, N., Shurmer, I., O'Connell, A., Torres, R., & Krassenburg, M. (2016, June). Sentinel-1 mission status. In Proceedings of EUSAR 2016: 11th European conference on synthetic aperture radar (pp. 1-6). VDE.

- Segarra, J., Buchaillot, M. L., Araus, J. L., & Kefauver, S. C. (2020). Remote sensing for precision agriculture: Sentinel-2 improved features and applications. Agronomy, 10(5), 641. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J., & Su, B. (2017). Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. Journal of sensors, 2017(1), 1353691. [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J. A., Penuelas, J., & Field, C. B. (1992). A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes in photosynthetic efficiency. Remote Sensing of environment, 41(1), 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J., Filella, I., & Gamon, J. A. (1995). Assessment of photosynthetic radiation-use efficiency with spectral reflectance. New Phytologist, 131(3), 291-296. [CrossRef]

- Garbulsky, M. F., Peñuelas, J., Gamon, J., Inoue, Y., & Filella, I. (2011). The photochemical reflectance index (PRI) and the remote sensing of leaf, canopy and ecosystem radiation use efficiencies: A review and meta-analysis. Remote sensing of environment, 115(2), 281-297.

- Zhang, C., Filella, I., Garbulsky, M. F., & Peñuelas, J. (2016). Affecting factors and recent improvements of the photochemical reflectance index (PRI) for remotely sensing foliar, canopy and ecosystemic radiation-use efficiencies. Remote Sensing, 8(9), 677. [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J. A., Kovalchuck, O., Wong, C. Y. S., Harris, A., & Garrity, S. R. (2015). Monitoring seasonal and diurnal changes in photosynthetic pigments with automated PRI and NDVI sensors. Biogeosciences, 12(13), 4149-4159. [CrossRef]

- Garbulsky, M. F. (2007). Remote estimation of carbon dioxide uptake of terrestrial ecosystems. Nature Precedings, 1-1.

- Zarco-Tejada, P. J., Hornero, A., Hernández-Clemente, R., & Beck, P. S. A. (2018). Understanding the temporal dimension of the red-edge spectral region for forest decline detection using high-resolution hyperspectral and Sentinel-2a imagery. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 137, 134-148. [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Sanchis, A., Piles, M., Muñoz-Marí, J., Adsuara, J. E., Pérez-Suay, A., & Camps-Valls, G. (2019). Synergistic integration of optical and microwave satellite data for crop yield estimation. Remote sensing of environment, 234, 111460. [CrossRef]

- Attema, E. P. W., & Ulaby, F. T. (1978). Vegetation modeled as a water cloud. Radio science, 13(2), 357-364. [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N., El Hajj, M., Zribi, M., & Bousbih, S. (2017). Calibration of the water cloud model at C-band for winter crop fields and grasslands. Remote Sensing, 9(9), 969. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q., Zribi, M., Escorihuela, M. J., & Baghdadi, N. (2017). Synergetic use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data for soil moisture mapping at 100 m resolution. Sensors,17(9), 1966. [CrossRef]

- Bao, X., Zhang, R., He, X., Shama, A., Yin, G., Chen, J., Zhang, H., & Liu, G. (2024). An Integrated Time-Series Relative Soil Moisture Monitoring Method Based on a SAR Backscattering Model. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing. [CrossRef]

- Santi, E., Paloscia, S., Pettinato, S., Entekhabi, D., Alemohammad, S. H., & Konings, A. G. (2016, July). Integration of passive and active microwave data from SMAP, AMSR2 and Sentinel-1 for Soil Moisture monitoring. In 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS) (pp. 5252-5255). IEEE.

- Fung, A. K. (1994). Microwave scattering and emission models and their applications.

- Oh, Y., Sarabandi, K., & Ulaby, F. T. (1992). An empirical model and an inversion technique for radar scattering from bare soil surfaces. IEEE transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 30(2), 370-381. [CrossRef]

- Dobson, M. C., Ulaby, F. T., Hallikainen, M. T., & El-Rayes, M. A. (1985). Microwave dielectric behavior of wet soil-Part II: Dielectric mixing models. IEEE Transactions on geoscience and remote sensing, (1), 35-46. [CrossRef]

- Pilia, S., Fontanelli, G., Santurri, L., Ramat, G., Baroni, F., Santi, E., Lapini, A., Pettinato, S., & Paloscia, S. (2023, November). Data integration of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 for evaluating vegetation biomass and water status. In 2023 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor) (pp. 694-698). IEEE.

- Pilia, S., Baroni, F., Fontanelli, G., Ramat, G., Palchetti, E., Paloscia, S., Pettinato, S., Santi, E., Santurri, L. (2024, July). Soil and Vegetation Water Status Monitoring by Integrating Optical and Microwave Satellite Data. In IGARSS 2024-2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (pp. 1470-1473). IEEE.

- https://world-soils.com/.

- https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-1/Mission_ends_for_Copernicus_Sentinel-1B_satellite.

- Barnes, E. M., Clarke, T. R., Richards, S. E., Colaizzi, P. D., Haberland, J., Kostrzewski, M., Waller, P., Choi, C., Riley, E., Thompson, T., Lascano, R.J., Li, H., Moran, M. S. (2000, July). Coincident detection of crop water stress, nitrogen status and canopy density using ground based multispectral data. In Proceedings of the fifth international conference on precision agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA (Vol. 1619, No. 6).

- Gamon, J. A., & Surfus, J. S. (1999). Assessing leaf pigment content and activity with a reflectometer. The New Phytologist, 143(1), 105-117. [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak, M. N., Gitelson, A. A., Chivkunova, O. B., & Rakitin, V. Y. (1999). Non-destructive optical detection of pigment changes during leaf senescence and fruit ripening. Physiologia plantarum, 106(1), 135-141. [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J., Baret, F., & Filella, I. (1995). Semi-empirical indices to assess carotenoids/chlorophyll a ratio from leaf spectral reflectance. Photosynthetica, 31(2), 221-230.

- Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D., & Moore, R. (2017). Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote sensing of Environment, 202, 18-27. [CrossRef]

- Clemente, J. P., Fontanelli, G., Ovando, G. G., Roa, Y. L. B., Lapini, A., & Santi, E. (2020, March). Google Earth Engine: Application of algorithms for remote sensing of crops in Tuscany (Italy). In 2020 IEEE Latin American GRSS & ISPRS Remote Sensing Conference (LAGIRS) (pp. 195-200). IEEE.

- Cai, Y., Zhang, M., & Lin, H. (2020). Estimating the urban fractional vegetation cover using an object-based mixture analysis method and Sentinel-2 MSI imagery. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 13, 341-350. [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, D., Gianelle, D., Scotton, M., & Dalponte, M. (2022). Estimating grassland vegetation cover with remote sensing: A comparison between Landsat-8, Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope imagery. Ecological Indicators, 141, 109102. [CrossRef]

- https://www.specmeters.com/FieldScout-TDR350-Soil-Moisture-Meter.

- https://handheld.psi.cz/products/plantpen-ndvi-and-pri/.

- Konings, A. G., Rao, K., & Steele-Dunne, S. C. (2019). Macro to micro: microwave remote sensing of plant water content for physiology and ecology. New Phytologist, 223(3), 1166-1172. [CrossRef]

- Ulaby, F. T., Moore, R. K., & Fung, A. K. (1982). Microwave remote sensing: Active and passive. Volume 2-Radar remote sensing and surface scattering and emission theory.

- https://www.lamma.toscana.it/meteo/osservazioni-e-dati/dati-stazioni.

- Takala, T. L., & Mõttus, M. (2016). Spatial variation of canopy PRI with shadow fraction caused by leaf-level irradiation conditions. Remote Sensing of Environment, 182, 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Ouaadi, N., Jarlan, L., Ezzahar, J., Khabba, S., Le Dantec, V., Rafi, Z., Zribi, M., & Frison, P. L. (2020, March). Water stress detection over irrigated wheat crops in semi-arid areas using the diurnal differences of Sentinel-1 backscatter. In 2020 Mediterranean and Middle-East Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (M2GARSS) (pp. 306-309). IEEE.

- Rockström, J., Karlberg, L., Wani, S. P., Barron, J., Hatibu, N., Oweis, T., Bruggeman A., Farahani J., & Qiang, Z. (2010). Managing water in rainfed agriculture—The need for a paradigm shift. Agricultural Water Management, 97(4), 543-550. [CrossRef]

- https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/european-and-global-drought-observatories/current-drought-situation-europe_en.

- Amiri, M. A., & Gocic, M. (2023). Analysis of temporal and spatial variations of drought over Serbia by investigating the applicability of precipitation-based drought indices. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 154(1), 261-274. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B., Gray, M., & Hunter, B. (2019). The social and economic impacts of drought. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 54(1), 22-31.

| S-1 Orbit | Angle of incidence [deg] | Overpass time [UTC] |

|---|---|---|

| 117-Ascending | 34.20 | 17:06 |

| 15-Ascending | 43.82 | 17:14 |

| 95-Descending | 43.18 | 05:19 |

| 168-Descending | 33.20 | 05:27 |

| Index | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NDRE | [41] | |

| RGR | [42] | |

| PSRI | [43] | |

| SIPI | [44] |

| Date S-1 | Date S-2 | Type of orbit |

|---|---|---|

| 07/07/2022 | 07/07/2022 | Descending |

| 14/07/2022 | 12/07/2022 | Descending |

| 19/07/2022 | 17/07/2022 | Descending |

| 20/07/2022 | 22/07/2022 | Ascending |

| 27/07/2022 | 27/07/2022 | Ascending |

| 01/08/2022 | 01/08/2022 | Ascending |

| 08/08/2022 | 06/08/2022 | Ascending |

| 13/08/2022 | 16/08/2022 | Ascending |

| 25/08/2022 | 26/08/2022 | Ascending |

| 31/08/2022 | 31/08/2022 | Descending |

| 27/07/2023 | 27/07/2023 | Ascending |

| 15/08/2023 | 16/08/2023 | Ascending |

| 26/08/2023 | 26/08/2023 | Descending |

| 07/09/2023 | 05/09/2023 | Descending |

| 12/09/2023 | 10/09/2023 | Descending |

| 13/09/2023 | 15/09/2023 | Ascending |

| 25/09/2023 | 25/09/2023 | Ascending |

| 01/10/2023 | 30/09/2023 | Descending |

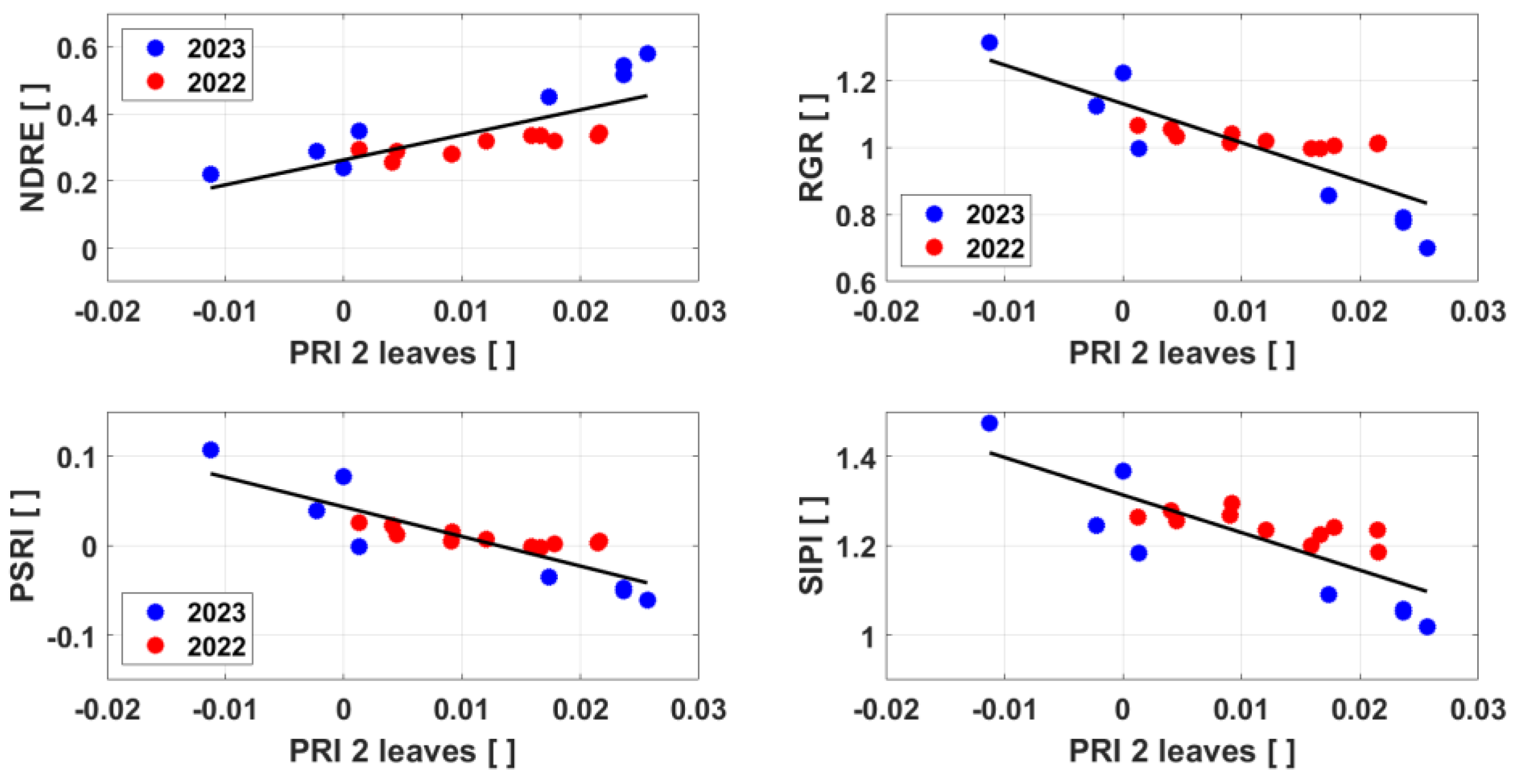

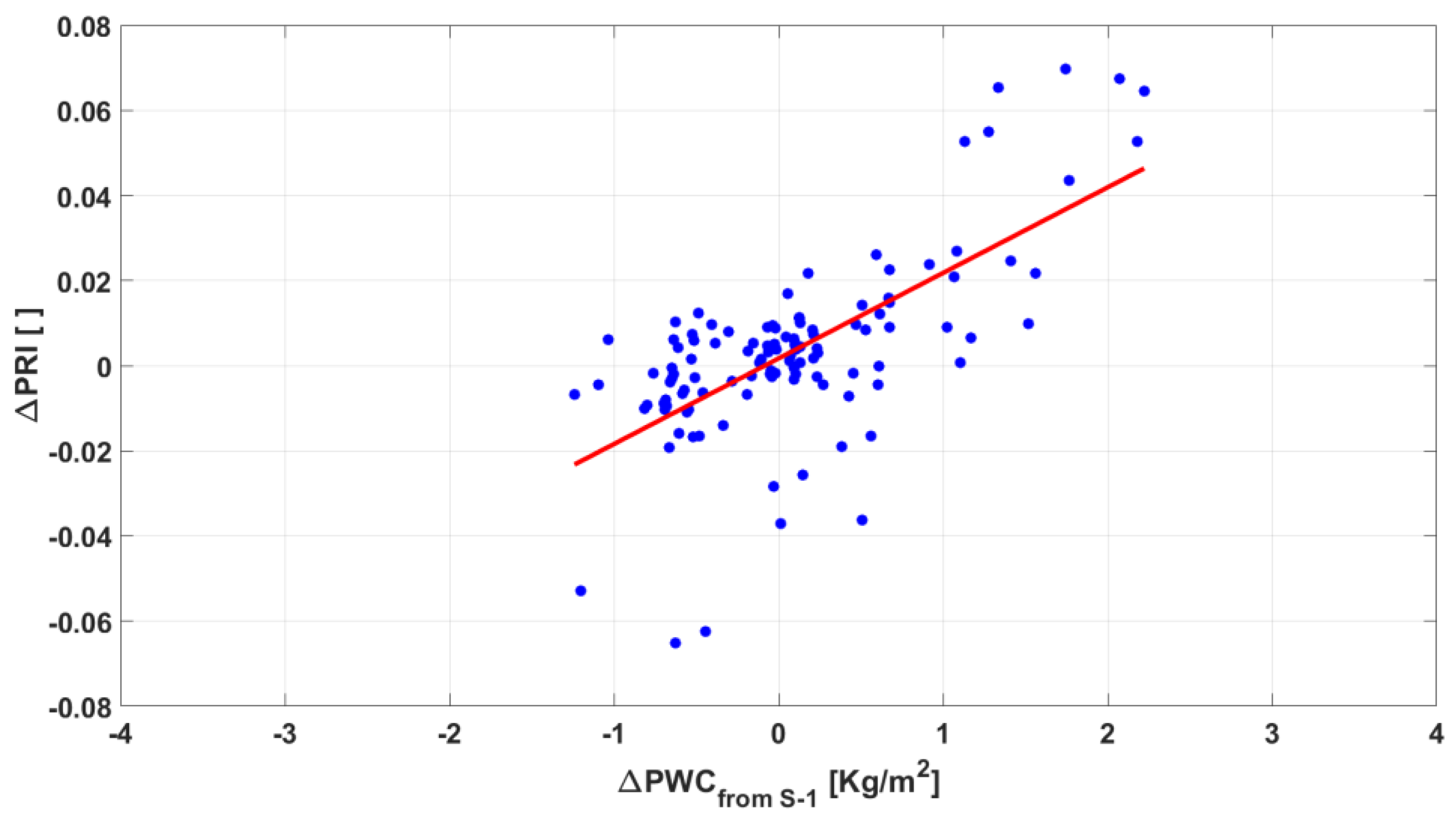

| Index | Regressions | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| NDRE | PRI + 0.2634 | 0.58 |

| RGR | PRI + 1.1308 | 0.70 |

| PSRI | PRI + 0.0434 | 0.73 |

| SIPI | PRI + 1.3135 | 0.64 |

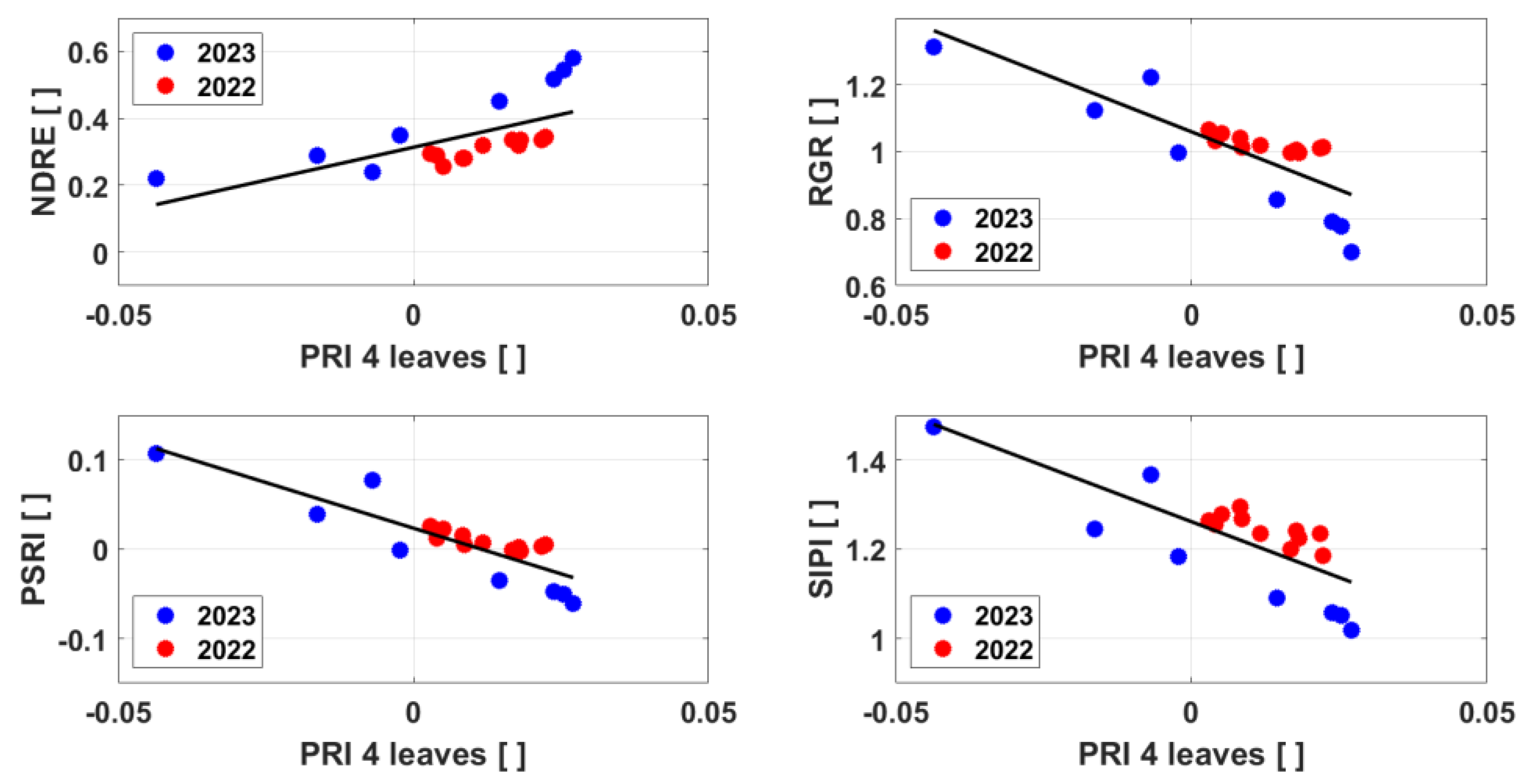

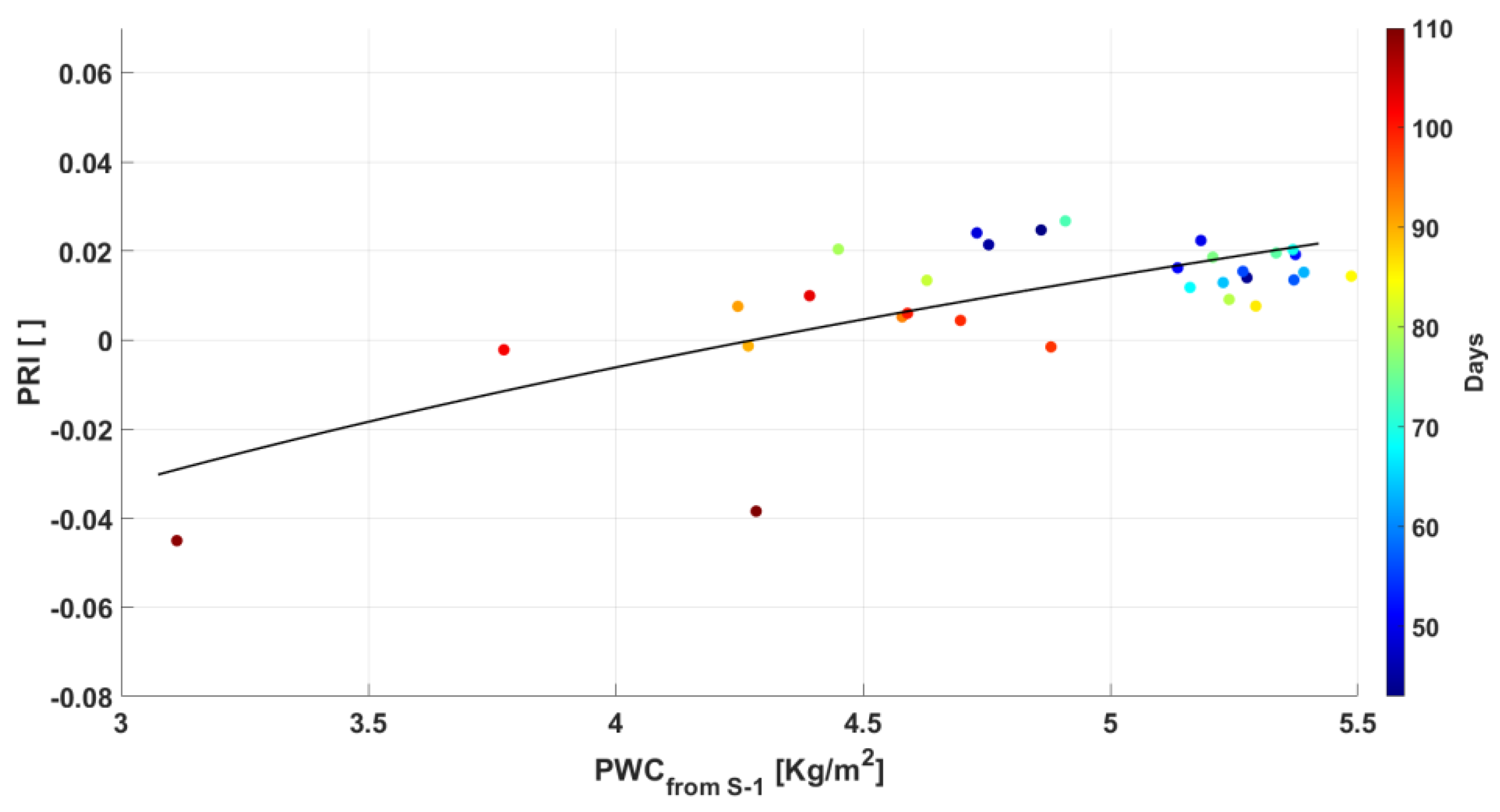

| Index | Fitting | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| NDRE | PRI + 0.3136 | 0.43 |

| RGR | PRI + 1.06 | 0.67 |

| PSRI | PRI + 0.0236 | 0.75 |

| SIPI | PRI + 1.2618 | 0.61 |

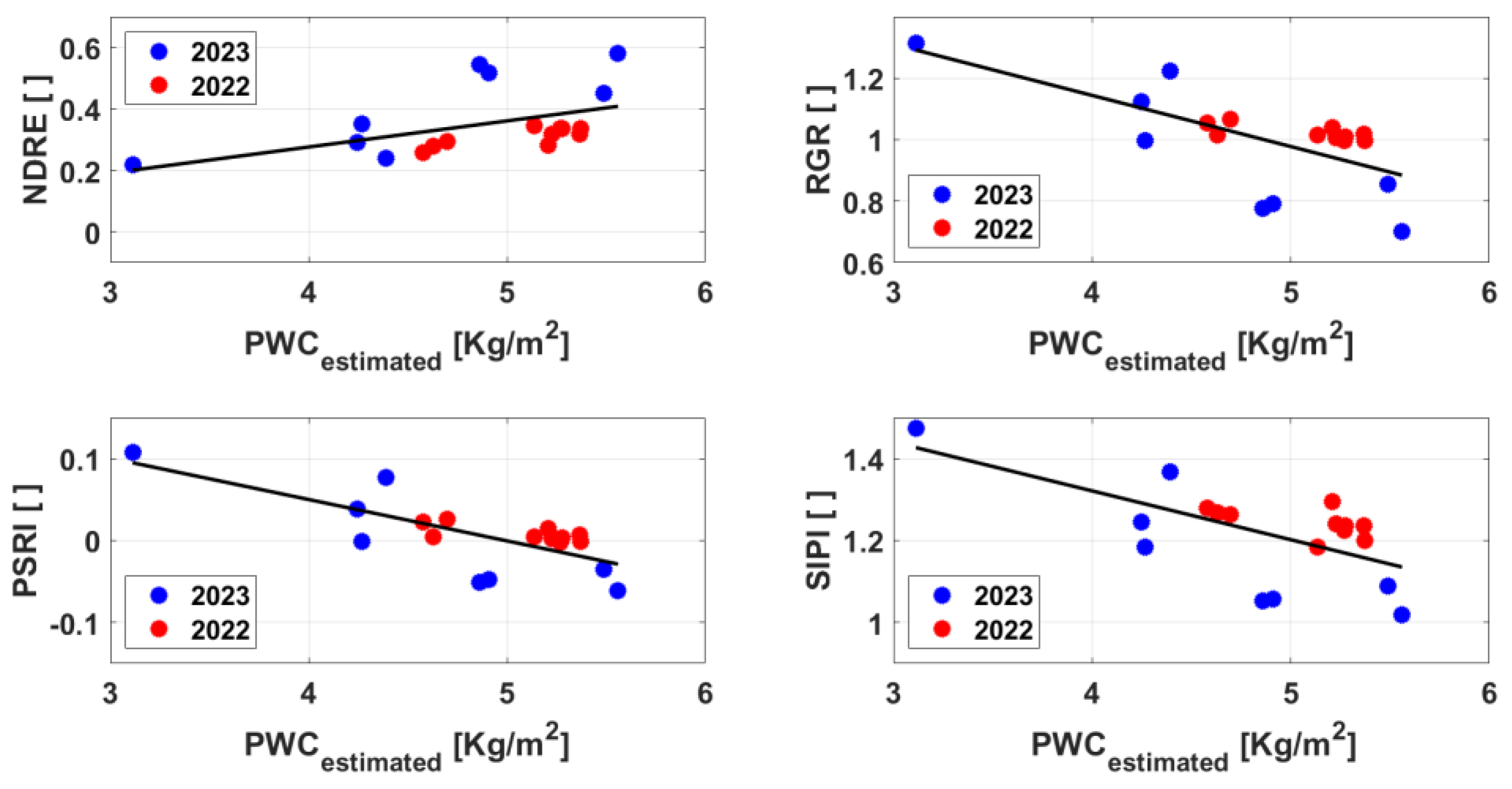

| Index | Fitting | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| NDRE | 0.0849·PWC - 0.0634 | 0.24 |

| RGR | -0.1664·PWC + 1.8097 | 0.46 |

| PSRI | -0.0505·PWC + 0.2521 | 0.54 |

| SIPI | -0.1191·PWC + 1.7976 | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).