Introduction

Dementia is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive deterioration of multiple cognitive functions beyond the effects of normal aging, leading to a loss of functionality and independence. With an aging population, it has become an increasingly significant public health concern. Enhanced recognition of neuropsychiatric symptoms may improve both patient management and the quality of life for caregivers [

1].

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is a disorder of emotional expression characterized by involuntary episodes of crying or laughing that are inappropriate to the social context [

2,

3]. PBA can occur in various neurological conditions, including traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, brain tumors, stroke, cerebellar disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases such a Parkinson's disease and dementia [

4]. The negative impacts of PBA on social interactions and quality of life contribute to both the disease burden and the burden on caregivers [

1]. Additionally, PBA can cause embarrassing and distressing situations for patients and their families [

5]. However, patients and their relatives often struggle to recognize the condition unless clinicians specifically inquire about it.

This study aimed to achieve three main objectives: to determine the prevalence of PBA among individuals with dementia, to explore its relationship with factors such as depression, anxiety, cognitive abilities, and apathy, and to assess whether PBA occurrence differs across various types of dementia.

Participants

This study was designed as a single-center, cross-sectional investigation. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee. A total of 108 dementia patients and 53 healthy volunteers without central neurological pathology were included. Dementia diagnoses were made based on established criteria: the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) criteria for Alzheimer's disease [

6], the International Behavioral Variant FTD Criteria Consortium (FTDC) for frontotemporal dementia [

7], the International Society for Vascular Behavioral and Cognitive Disorders criteria for vascular dementia [

8], and McKeith et al.'s 2017 criteria for Lewy body dementia [

9].

Patients in stages I and II of dementia were included regardless of age or gender, with no distinction made between dementia subtypes. The distribution of patients was comparable to community prevalence rates for each dementia type. Patients who had experienced metabolic or infection-related events leading to delirium within the past three months were excluded from the study.

Procedure

All patients were informed about the study, and consent was obtained from either the patient or their legal guardian. Demographic data were recorded, and both the patient and healthy control groups completed the CNS-LS scale. The MMSE, GDS, GAS, and AES scales were administered exclusively to the patient group.

Caregivers were asked whether their patients experienced laughing or crying episodes (yes/no), and the total percentage was calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Frequency analysis was performed to examine the demographic characteristics of the participants. Scores from the MMSE, GDS, GAS, AES, and CNS-LS scales were calculated, and relevant descriptive statistics were presented. A cut-off score of 13 was established for the CNS-LS, with individuals scoring 13 or higher classified as having PBA [

15]. Mean comparison tests were conducted, and normality was assessed using skewness and kurtosis values. Independent sample t- tests and one-way ANOVA were used for group comparisons. Pearson’s chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were applied to categorical variables. Correlations were visualized using the ggcorrplot package in R. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0.05. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 27.

Results

Among the total 212 (110 females) patients included in the study. The distribution of dementia subtypes was as follows: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was the most common subtype, accounting for 52 patients (24.53%), followed by Vascular dementia (VD) with 45 patients (21.23%). Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) was observed in 30 patients (14.15%), while Lewy body dementia (LBD) was present in 32 patients (15.09%). Additionally, a healthy control group consisted of 53 individuals (25.00%). These findings indicate a diverse representation of dementia subtypes, allowing for comparative analysis across different clinical presentations. The mean age of the dementia group was 74.03 ± 8.20 years, while the mean age of the healthy control group was 58.77 ± 14.30 years.The numerical distribution of the study group according to dementia subtypes and the mean CNS-LS scores are presented in

Table 1.

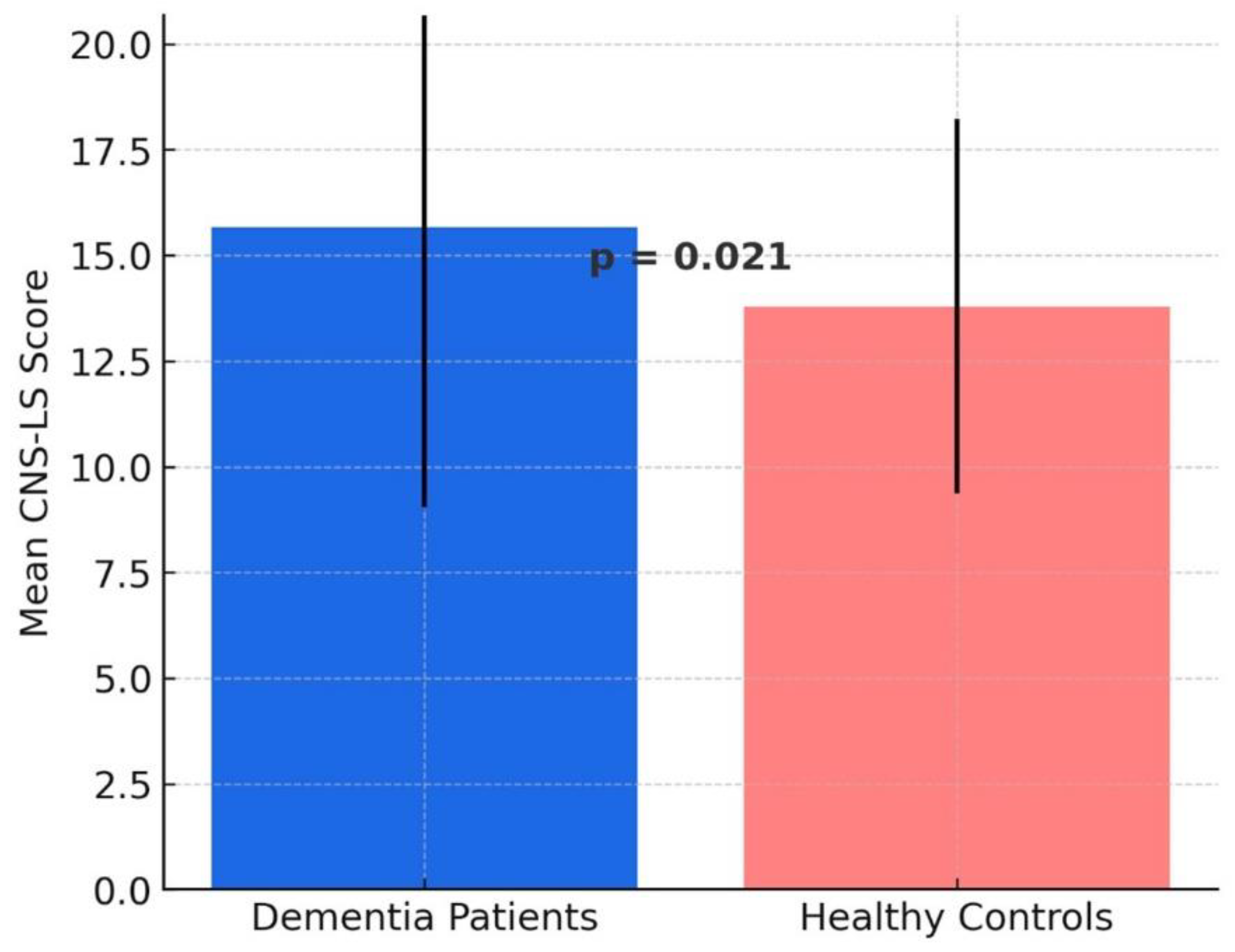

When comparing the total patient group (including AD, FTD, VD, and LBD) with the healthy control group, the mean CNS-LS score was found to be higher in the patient group (

15.67 ± 6.62) compared to the healthy controls (

13.79 ± 4.43). A two-sample t-test revealed a statistically significant difference between the total dementia group and the healthy controls (

p = 0.021), indicating that individuals with dementia exhibit higher CNS-LS scores compared to cognitively healthy individuals (

Figure 1).

The mean CNS-LS scores varied across the groups, with the highest mean score observed in the

VD group (18.55 ± 7.38), followed by FTD (17.00 ± 5.59), AD (14.98 ± 7.21), LBD (13.89 ± 5.04), and the lowest in the Healthy Control group (12.87 ± 4.37). One-way ANOVA analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in CNS-LS scores among the dementia subtypes (p < 0.001) (

Table 1)

Pairwise comparisons demonstrated that VD patients had significantly higher CNS-LS scores compared to AD (p = 0.0002), LBD (p = 0.0001), and the Healthy Control group (p = 0.0001). Similarly, FTD patients exhibited significantly higher CNS-LS scores compared to AD (p = 0.0058), LBD (p = 0.0031), and the Healthy Control group (p = 0.0045). However, there was no significant difference in CNS-LS scores between AD and LBD (p = 0.9401) or between AD and the Healthy Control group (p = 0.7297) (

Table 2)

These results suggest that CNS-LS scores differ among dementia subtypes, with VD and FTD patients exhibiting the highest scores, while AD and LBD patients showed similar scores to the Healthy Control group.

Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between PBA scores (CNS-LS) and other commonly used scales in dementia treatment (

Table 3). According to the analysis in

Table 3, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) showed borderline significant negative correlations with other scales. The correlations between MMSE and GDS (-0.182, p = 0.054), GAS (- 0.181, p = 0.059), and CNS-LS (-0.171, p = 0.057) were close to statistical significance, suggesting that as cognitive function declines, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PBA may become more pronounced. A strong positive correlation was observed between the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and the Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS) (r = 0.675, p < 0.001), indicating that patients with higher levels of depression also tend to have increased anxiety. Additionally, a weaker but significant positive correlation was found between GDS and PBA (CNS-LS) (r = 0.236, p = 0.011), suggesting that higher depression scores may be associated with more severe PBA symptoms. Similarly, a significant positive correlation was observed between GAS and CNS-LS (r = 0.369, p < 0.001), indicating that PBA symptoms are more strongly associated with anxiety than with depression. These findings suggest that while PBA is linked to mood disturbances, its association with cognitive impairment appears to be weaker or borderline significant.

Among patients with CNS-LS scores of 13 and above, 45.95% had depression and 39.19% had anxiety.

Caregivers responded 'yes' in 70% of cases when asked about the presence of laughing/crying episodes in a yes/no format.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the incidence of PBA in dementia patients compared to healthy individuals and examined its relationship with depression, anxiety, cognitive functions, and apathy. Additionally, we investigated whether PBA prevalence varies across different dementia subtypes. Our findings revealed that dementia patients had significantly higher CNS-LS scores than healthy controls, suggesting that PBA is a prevalent condition among individuals with dementia.

The diagnosis of PBA is based on clinical history and neurological examination. Diagnostic criteria include emotional responses inappropriate to the situation, a lack of correlation between emotional experience and expression, inability to control the duration and intensity of episodes, emotional expression not providing a sense of relief, divergence from previous emotional responses, absence of specific triggers, significant social or occupational distress, and exclusion of other neurological or psychiatric conditions independent of substance use [

17].

Differences in PBA Across Dementia Subtypes

In the literature, the prevalence of PBA among dementia patients ranges from 5% to 50% [

2,

3,

17]. In our study, this rate was found to be 53%, aligning with prior reports. Specifically, the prevalence of PBA in AD patients was 57.45%, which is considerably higher than the 16.4% prevalence reported in a previous meta-analysis [

18]. This discrepancy may be due to differences in screening methods. In our study, CNS-LS scores above 13 were classified as subclinical PBA, potentially leading to the identification of a broader patient population.

In our study, PBA scores in AD and LBD patients were similar to those in the healthy control group, with no significant differences observed. This finding differs from some previous studies.

A key aspect of our study was the assessment of PBA prevalence across different dementia subtypes. Our findings demonstrated that PBA scores varied significantly among dementia subtypes. The highest CNS-LS scores were observed in VD and FTD patients, with both groups exhibiting significantly higher PBA scores compared to AD, LBD, and healthy controls. Previous research has reported frequent emotional regulation impairments in FTD patients and an increased risk of PBA in VD patients due to frontal-subcortical dysfunction. Our study supports these findings [

2].

Clinical Associations of PBA and Dementia

Consistent with previous studies, we identified a significant positive correlation between CNS-LS scores and both depression and anxiety. This finding further supports the frequent co-occurrence of PBA with these mood disorders. In our study, 45.95% of patients with CNS-LS scores ≥13 had depression, while 39.19% had anxiety, in agreement with prior research highlighting the strong association between PBA and psychiatric symptoms [

5,

19].

However, no significant correlation was found between PBA and apathy.

Additionally, we observed a borderline significant negative correlation between CNS-LS and MMSE scores, which aligns with previous studies suggesting that PBA symptoms become more pronounced as cognitive decline progresses [

20]. This finding suggests that PBA may be more prevalent in advanced stages of dementia or in individuals with more severe cognitive impairment.

Underrecognition and Clinical Significance of PBA

Despite its high prevalence, PBA remains frequently underdiagnosed in clinical practice. As reported in previous studies [

3], our study also found that many patients meeting CNS-LS criteria for PBA had not previously been diagnosed. This suggests that PBA is often overlooked during routine clinical assessments, especially when specific screening is not performed.

Caregivers often misinterpret PBA symptoms as general emotional sensitivity or a natural consequence of the disease, rather than as a distinct emotional dysregulation disorder. This misinterpretation reduces clinical awareness of PBA and may hinder access to appropriate treatment. In our study, 70% of patients reported experiencing crying episodes. Previous research has indicated that pathological crying is more common than pathological laughing [

21]. However, this distinction was not specifically assessed in our study.

PBA is a disinhibition syndrome that can be mistaken for mood disorders [

2]. However, there are important distinctions between PBA and depression. PBA episodes are typically shorter than depressive episodes, and the mismatch between mood and emotional expression is not characteristic of depression. Furthermore, neurovegetative symptoms such as sleep disturbances and appetite changes, commonly seen in depression, are absent in PBA. Patients with PBA often cannot suppress these emotional reactions, and their expressions are disproportionate to their actual emotional state [

22].

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that PBA is more prevalent in dementia patients, particularly in VD and FTD subtypes. The strong association between PBA, depression, and anxiety highlights the need for comprehensive neuropsychiatric assessment in dementia patients. The underrecognition of PBA may limit access to appropriate treatment, negatively impacting patients’ quality of life. Therefore, raising clinical awareness and implementing systematic screening methods may improve the accurate diagnosis and management of PBA. Further research is needed to better understand the pathophysiological mechanisms of PBA across different dementia subtypes.

Limitations of the Study

This study did not include imaging findings, which limits its ability to explore structural or functional neurological correlates of PBA. Additionally, the cross-sectional design prevents observation of changes over time. Future studies should examine the relationship between PBA and quality of life and investigate whether pathological crying or laughing is more prevalent. Including quality of life assessments and daily living conditions could provide clearer insights.

Suggestions for Further Studies

Elucidating the pathophysiology of PBA through functional imaging methods or biomarkers may improve diagnosis. Investigating the impact of PBA on quality of life can provide valuable information on its daily burden. Increased knowledge of PBA may also facilitate the development of more targeted treatments. Prospective studies could offer a better understanding of how neuropsychiatric symptoms progress in different dementia types.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who helped with the study.

Ethical Approval

University of Health Sciences, Hamidiye Faculty of Medicine, Sancaktepe Sehit Prof. Dr. Ilhan Varank SUAM Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (date: 20.02.2024, number: 2024/30).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Use of AI for Writing Assistance

Not used.

Financial Disclosure

None.

References

- Goldin, D.S. Pseudobulbar Affect: An Overview. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2020, 58, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Simmons, Z. Pseudobulbar affect: prevalence and management. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2013, 9, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.; Pratt, H.; Schiffer, R.B. Pseudobulbar affect: the spectrum of clinical presentations, etiologies and treatments. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvé, W.M. Recognizing and treating pseudobulbar affect. CNS Spectr. 2016, 21, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateno, A.; Jorge, R.E.; Robinson, R.G. Pathological laughing and crying following traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascovsky, K.; Hodges, J.R.; Knopman, D.; Mendez, M.F.; Kramer, J.H.; Neuhaus, J.; van Swieten, J.C.; Seelaar, H.; Dopper, E.G.P.; Onyike, C.U.; et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011, 134, 2456–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, P.; Kalaria, R.; O’Brien, J.; Skoog, I.; Alladi, S.; Black, S.E.; Blacker, D.; Blazer, D.G.; Chen, C.; Chui, H.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2014, 28, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.-P.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; Attems, J.; Ballard, C.G.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngen, C.; Ertan, T.; Eker, E.; Yaşar, R.; Engin, F. Reliability and validity of the standardized Mini Mental State Examination in the diagnosis of mild dementia in Turkish population. Turk. Psikiyatr. Derg. 2002, 13, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pifer, M.A.; Segal, D.L. Geriatric Anxiety Scale: Development and Preliminary Validation of a Long-Term Care Anxiety Assessment Measure. Clin. Gerontol. 2020, 43, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, R.S.; Biedrzycki, R.C.; Firinciogullari, S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991, 38, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.A.; Berg, J.E.; Pope, L.E.; Callahan, J.D.; Wynn, D.; Thisted, R.A. Validation of the CNS emotional lability scale for pseudobulbar affect (pathological laughing and crying) in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. 2004, 10, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togrol, R.E.; Demir, S. Reliability, validity and validation of the CNS emotional lability scale for pseudobulbar affect on multiple sclerosis in Turkish patients. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, S.; Moore, M.; Gawel, M.; Feinstein, A. Pathological laughing and crying in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an association with prefrontal cognitive dysfunction. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 169, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabizadeh, F.; Nikfarjam, M.; Azami, M.; Sharifkazemi, H.; Sodeifian, F. Pseudobulbar affect in neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review and meta- analysis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 100, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkstein, S.E.; Migliorelli, R.; Tesón, A.; Petracca, G.; Chemerinsky, E.; Manes, F.; Leiguarda, R. Prevalence and clinical correlates of pathological affective display in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1995, 59, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karve, S.J.; Ringman, J.M.; Lee, A.S.; Juarez, K.O.; Mendez, M.F. Comparison of clinical characteristics between familial and non-familial early onset Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. 2012, 259, 2182–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Murai, T.; Bauer-Wittmund, T.; von Cramon, D.Y. Paroxetine versus citalopram treatment of pathological crying after brain injury. Brain Inj. 1999, 13, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.R.; Reiss, J.P. The epidemiology and pathophysiology of pseudobulbar affect and its association with neurodegeneration. Degener. Neurol. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2013, 3, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).