Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Concrete Mix Preparation Procedure

Measurement

3. Results & Discussion

Concrete Properties

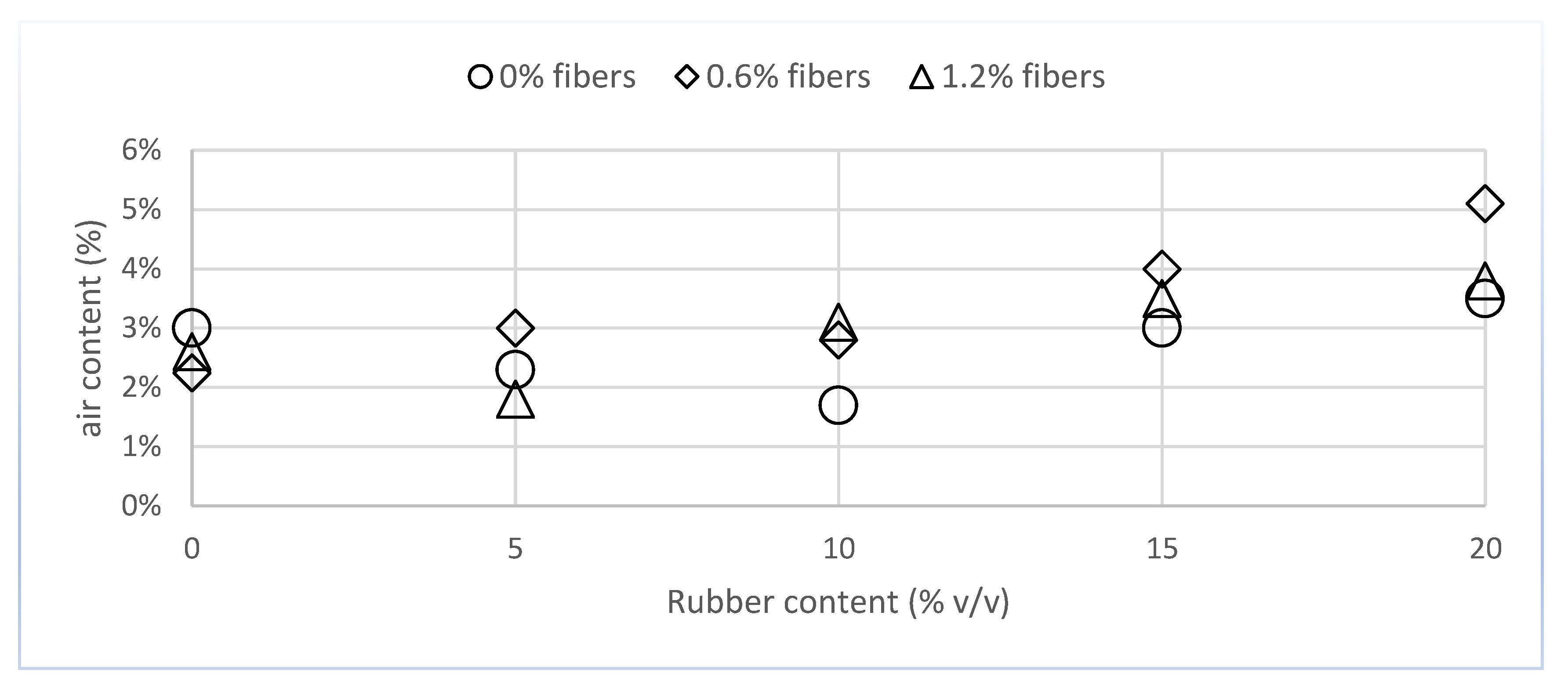

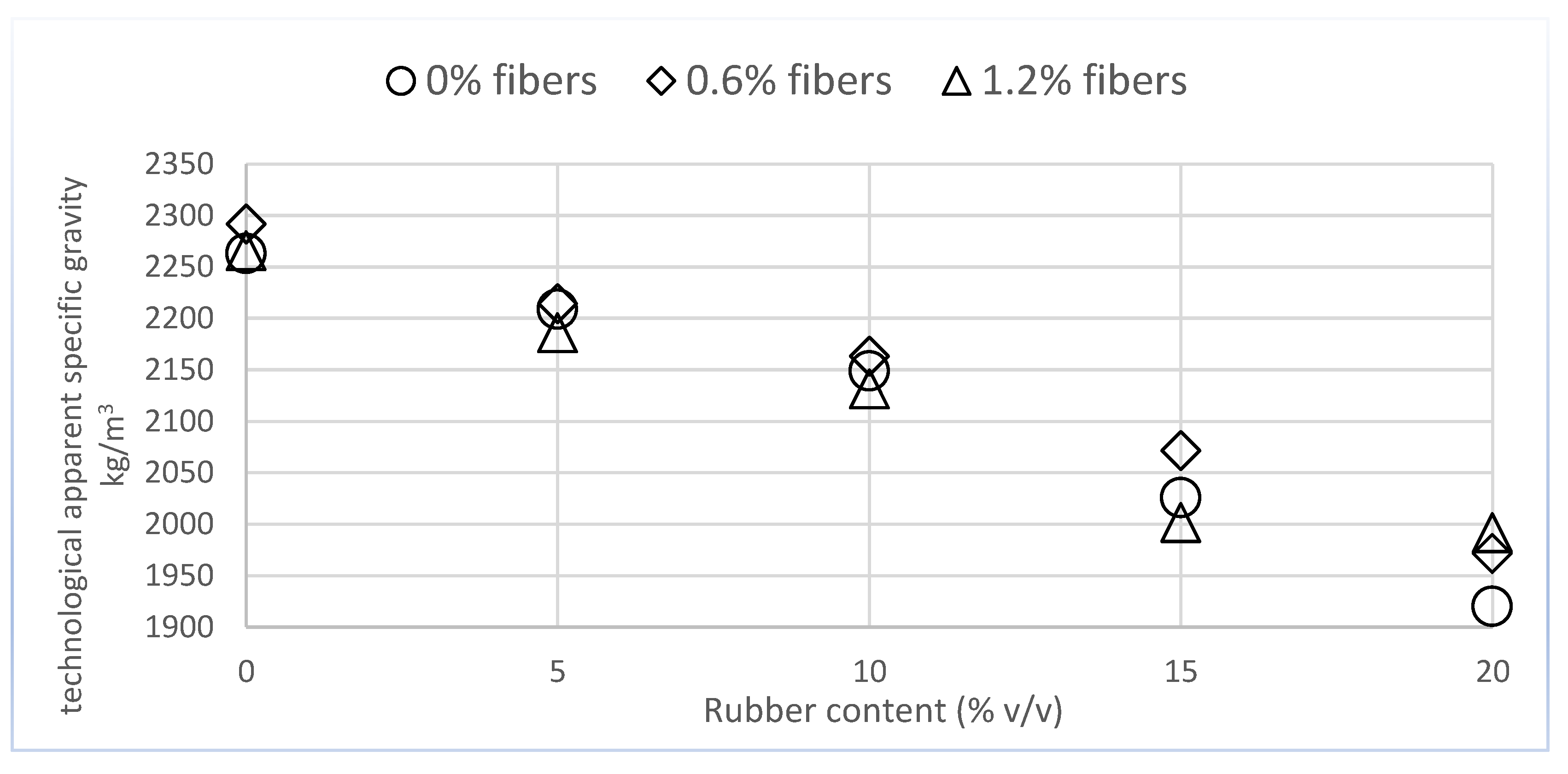

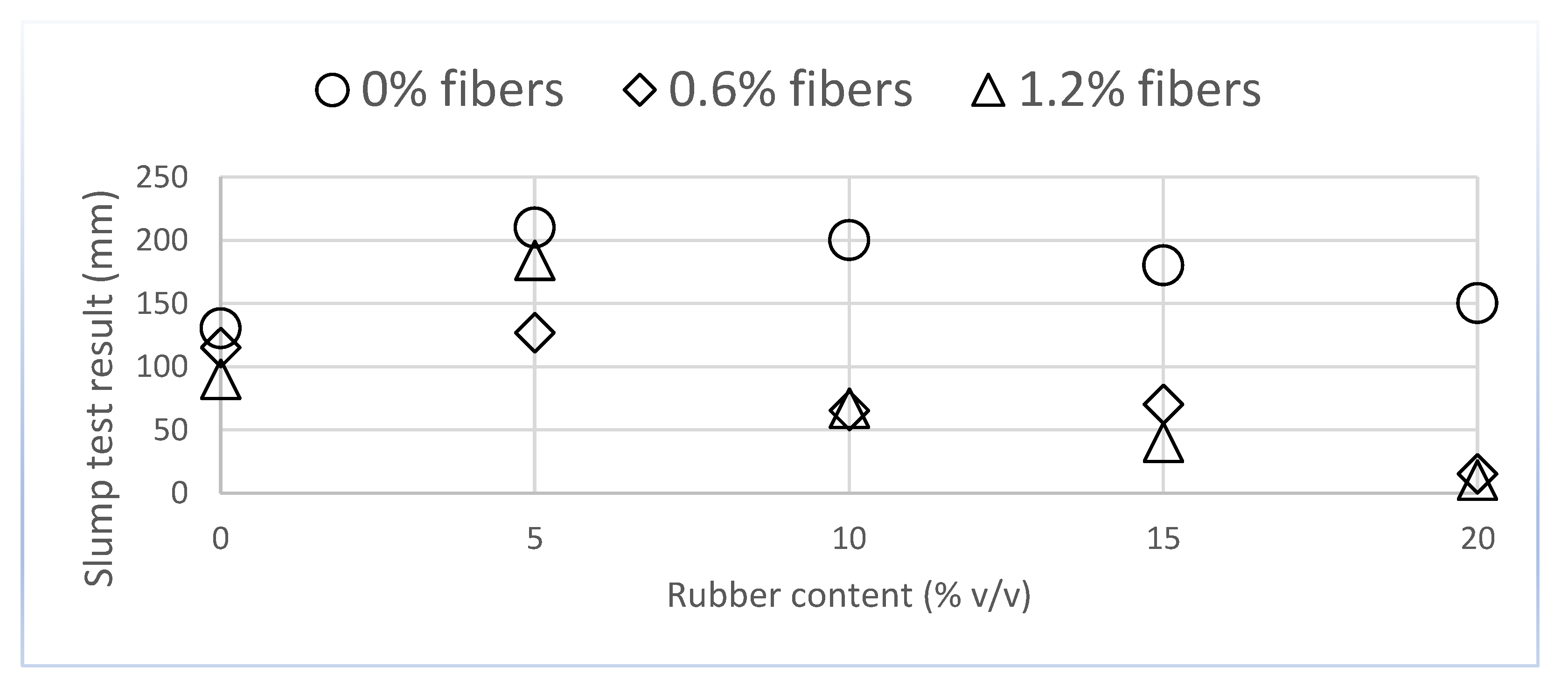

Fresh Concrete

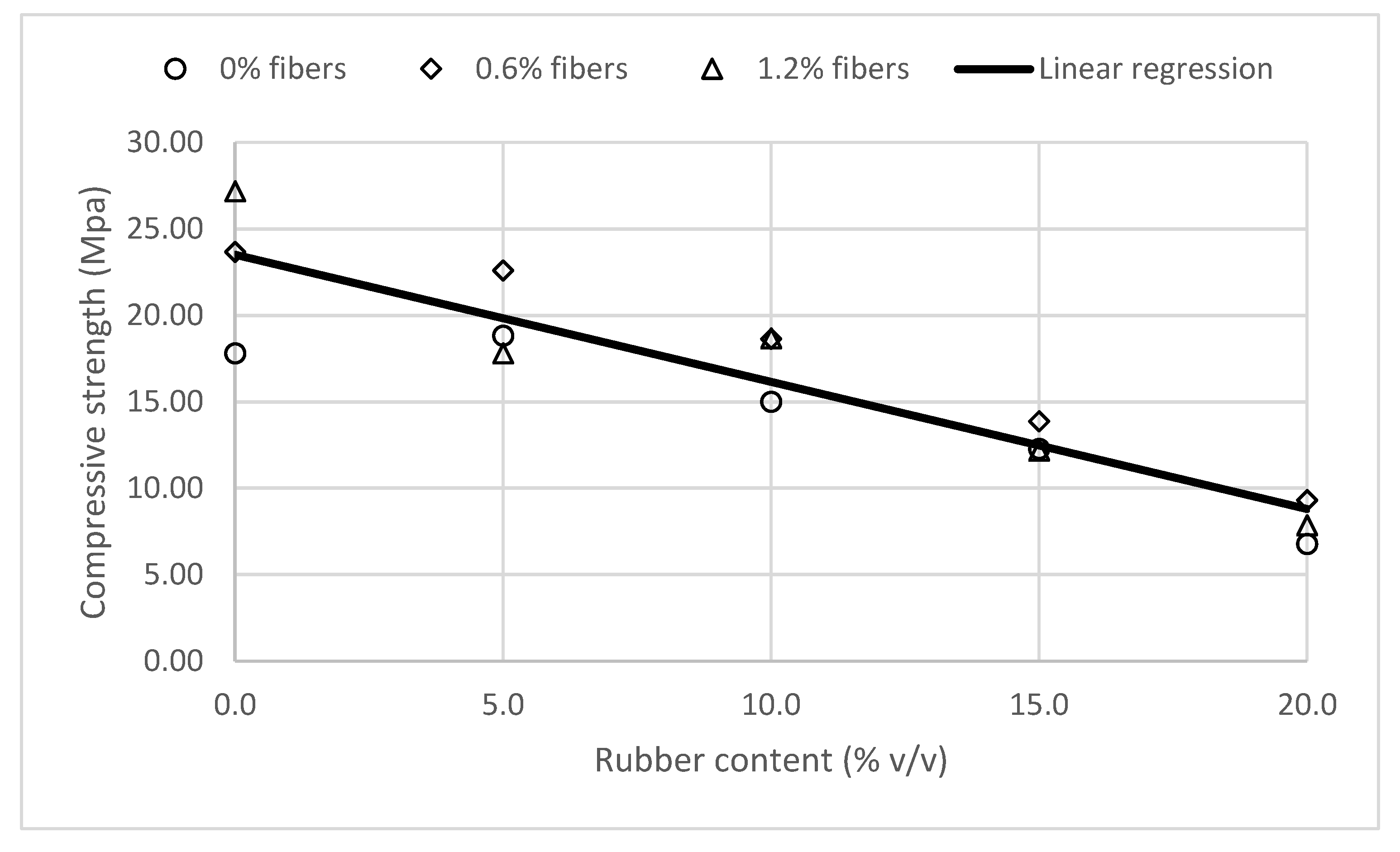

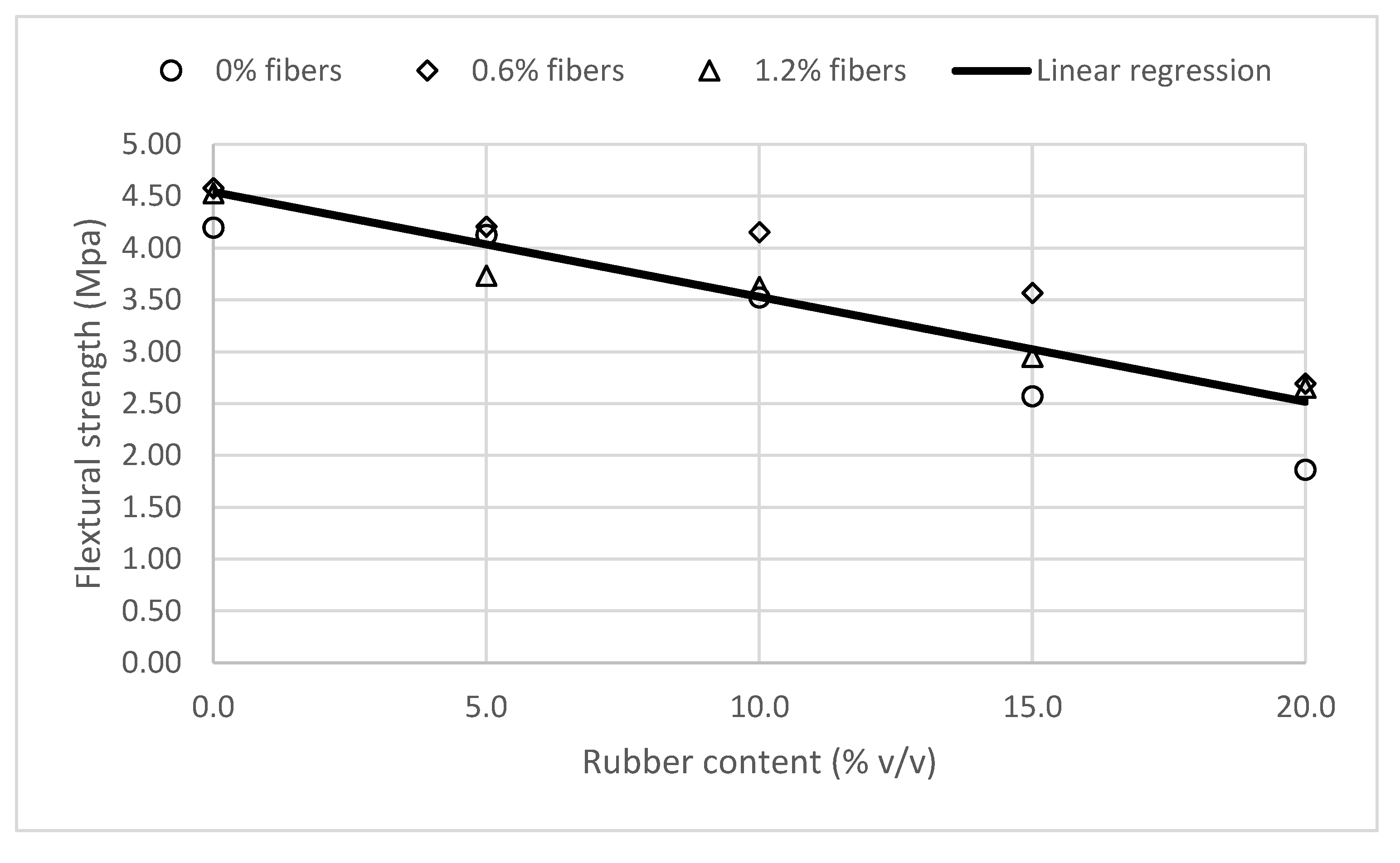

Harden Concrete

Energy to Failure

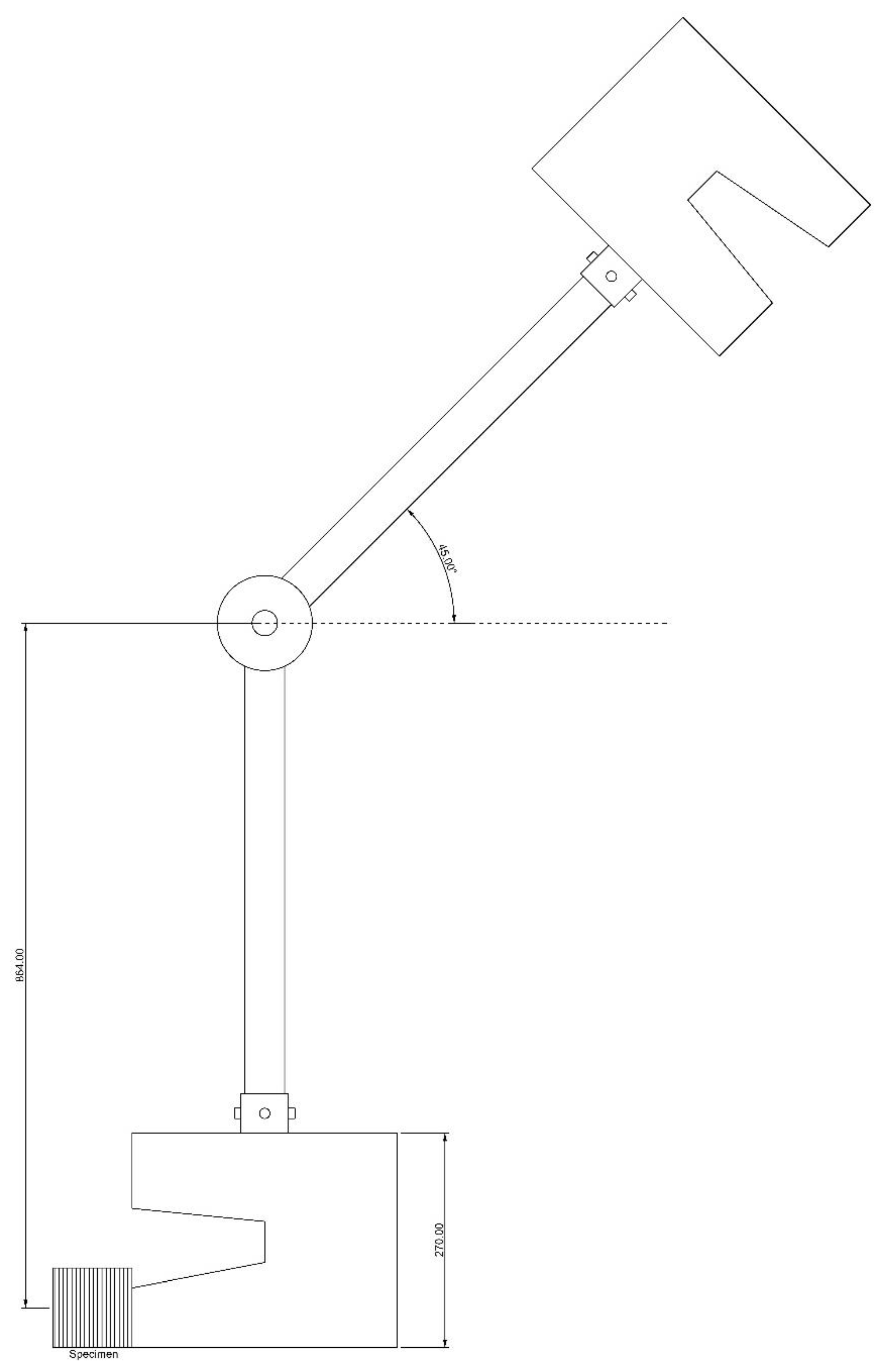

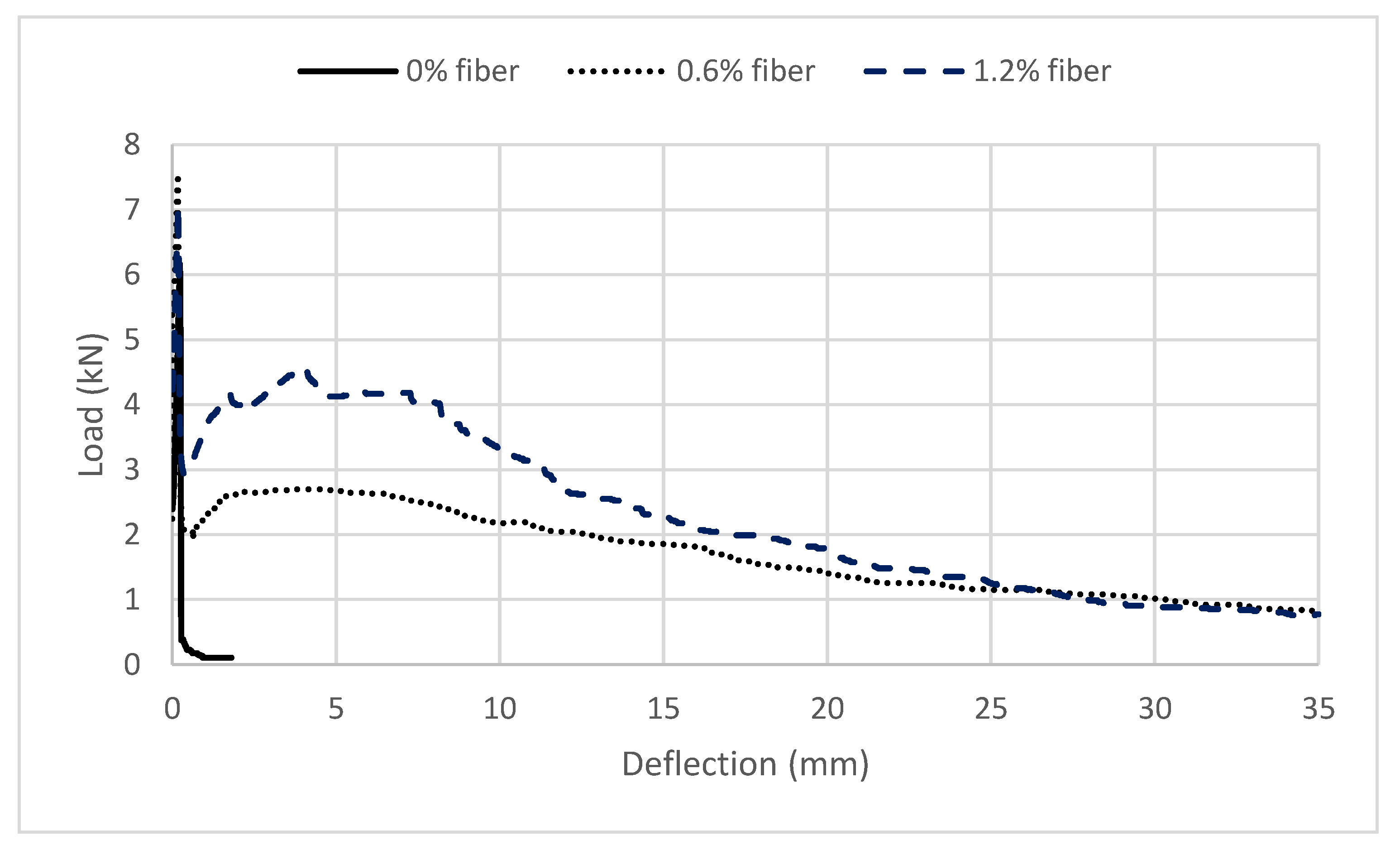

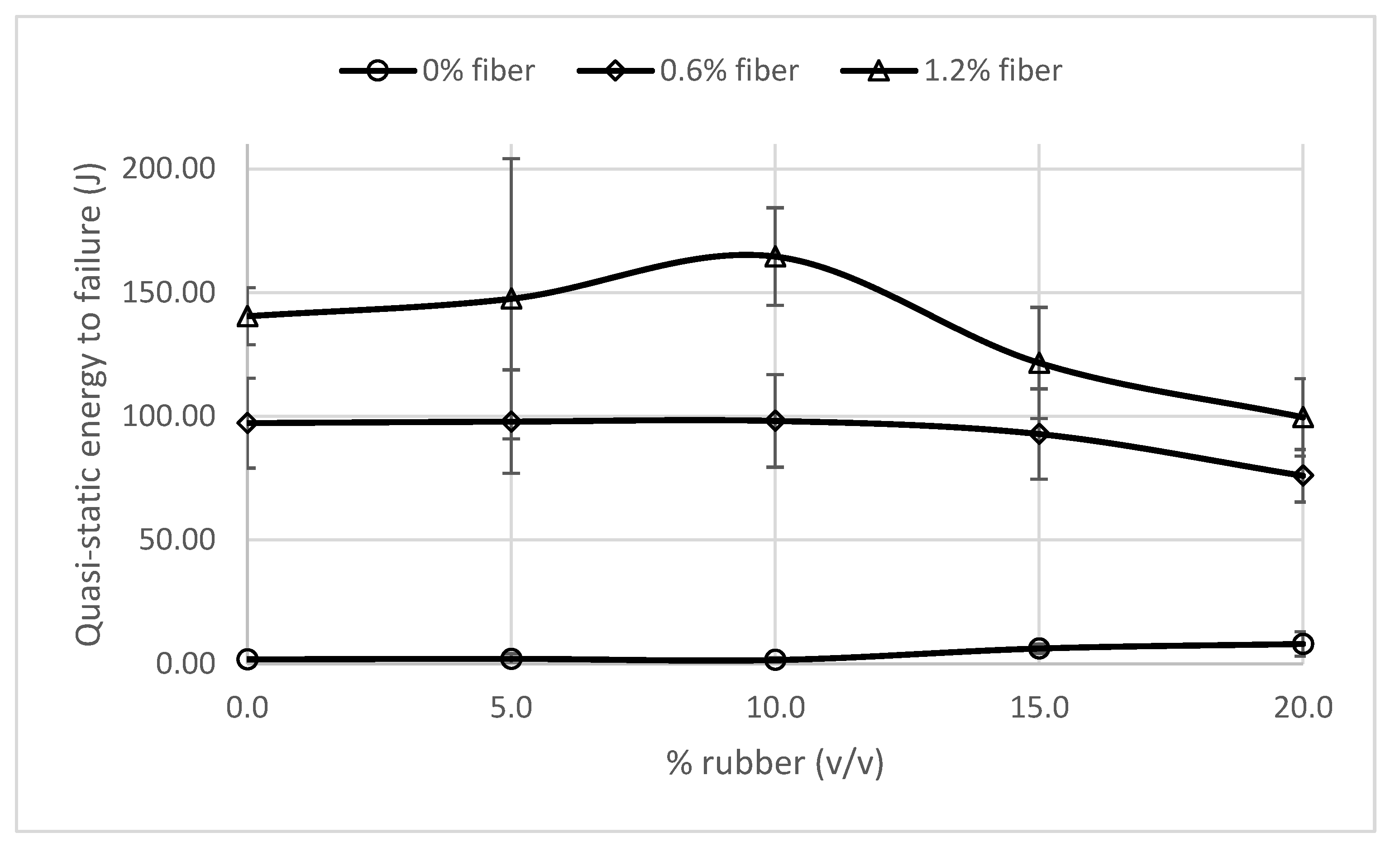

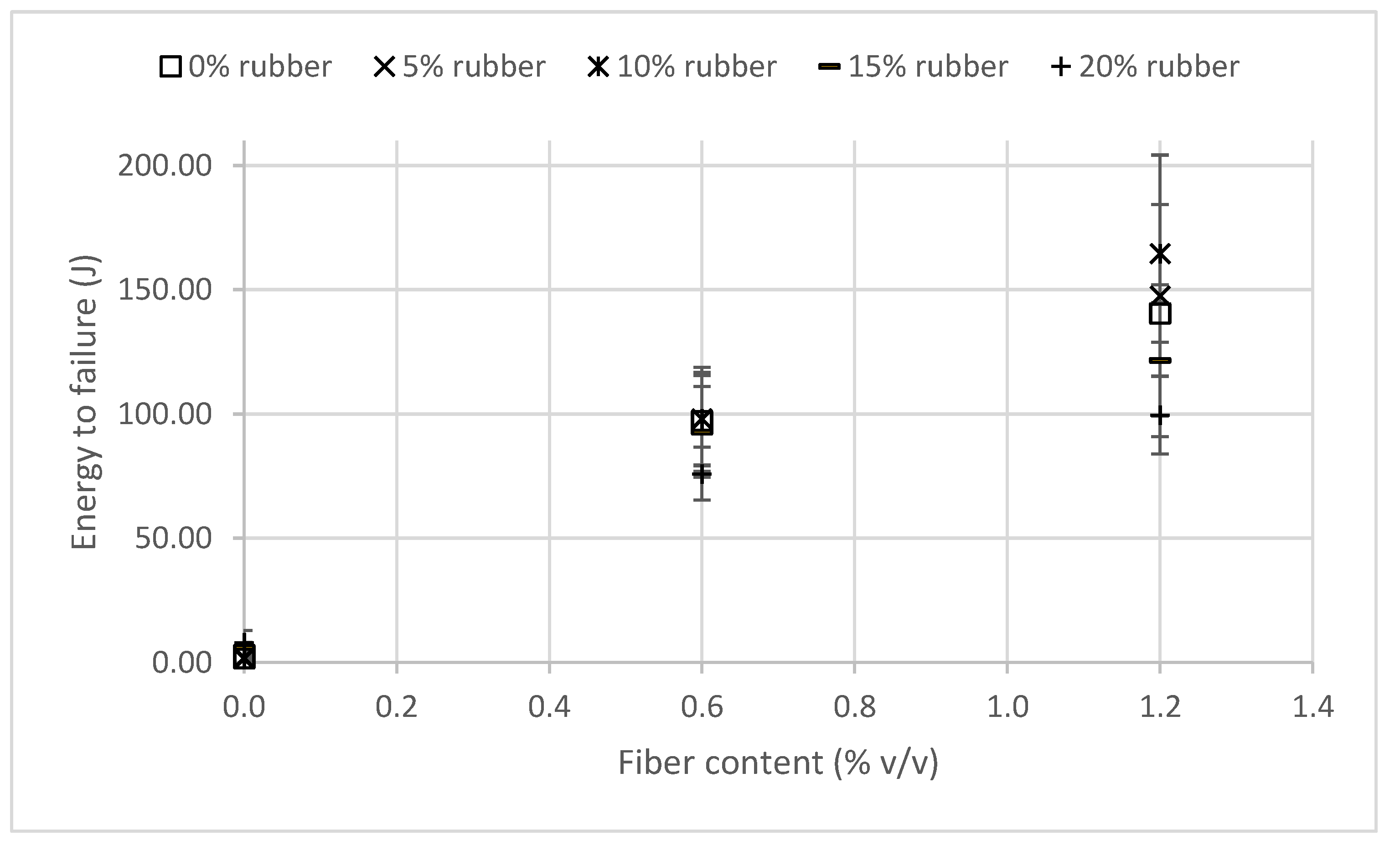

Quasi-Static

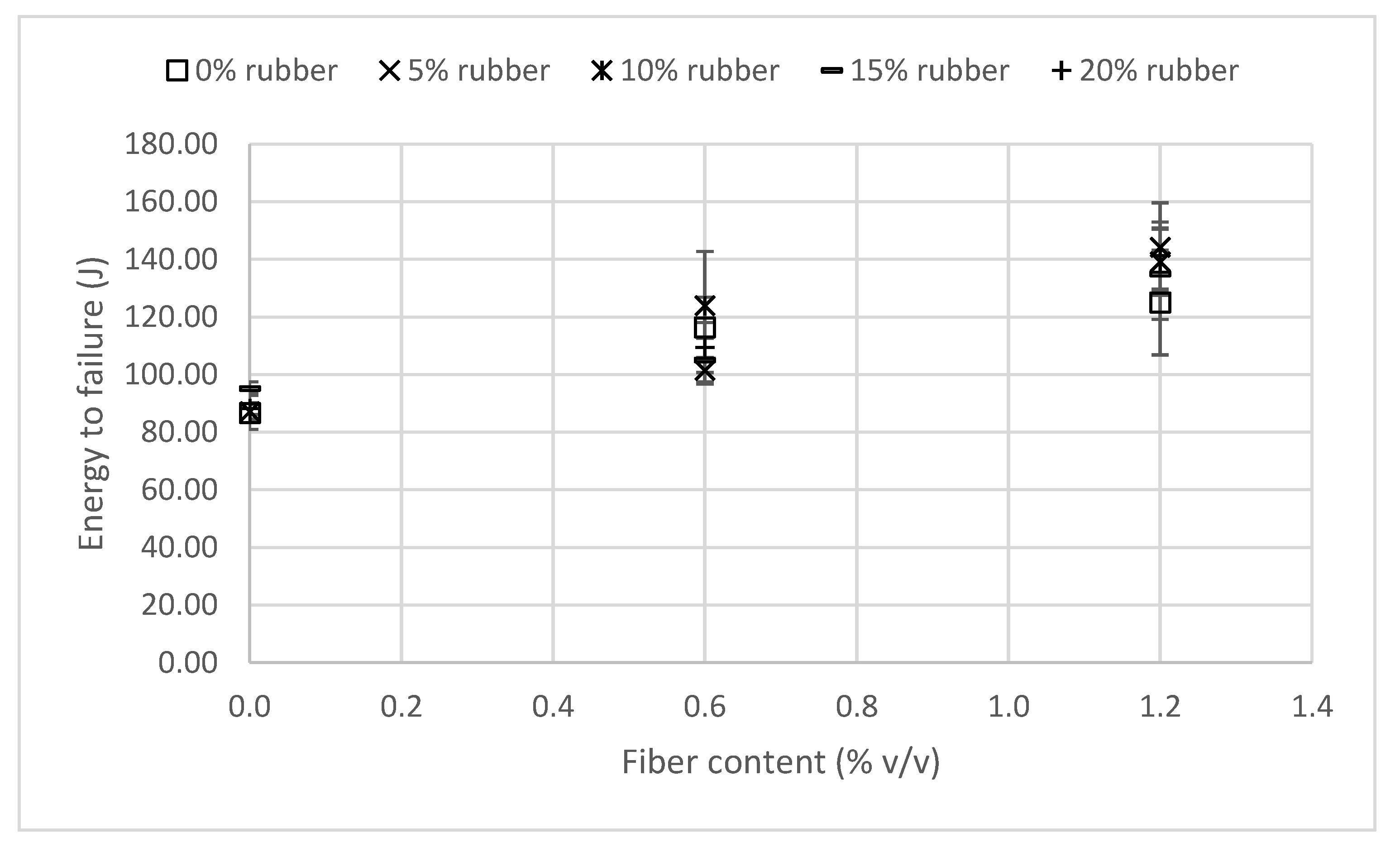

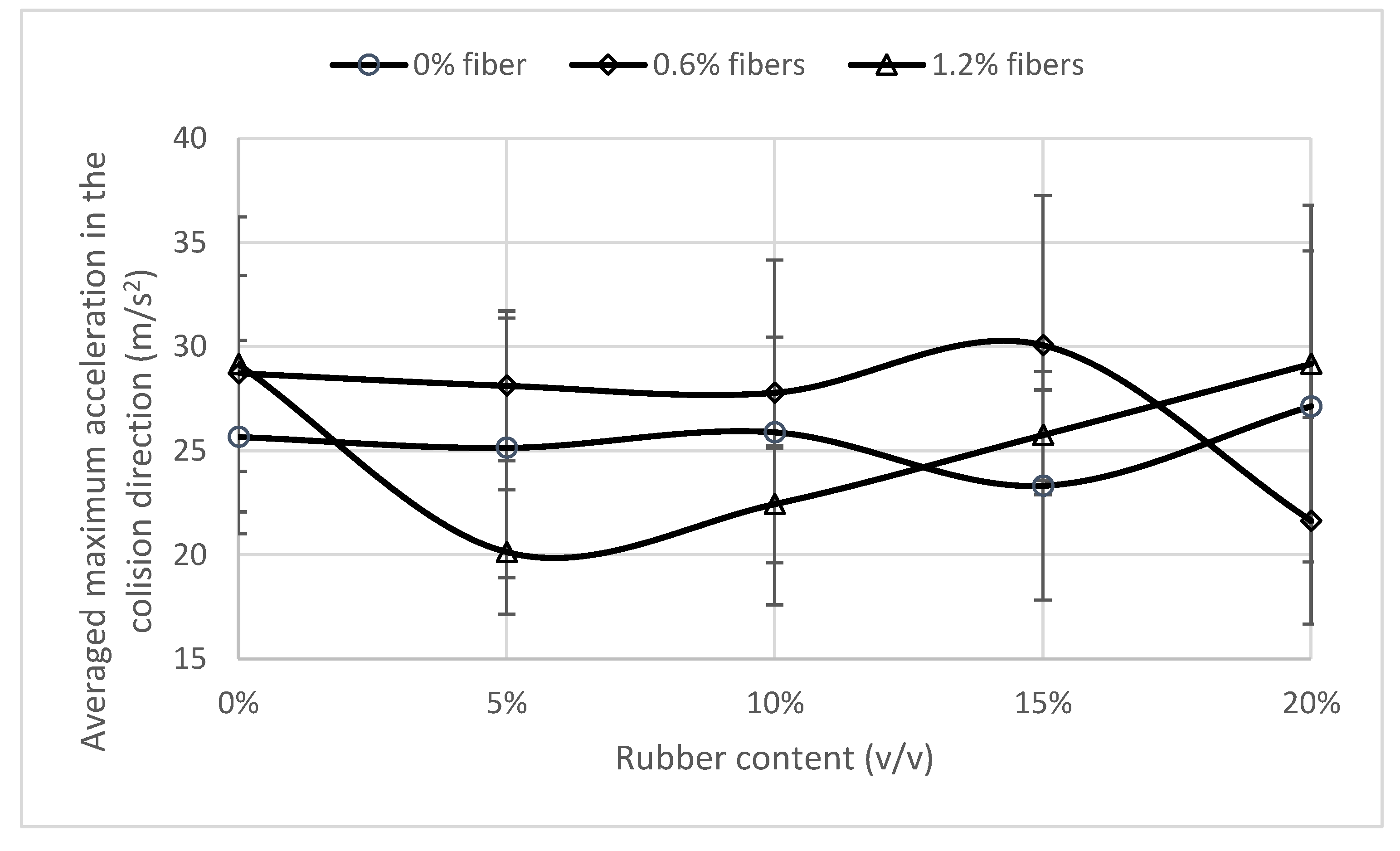

Dynamic

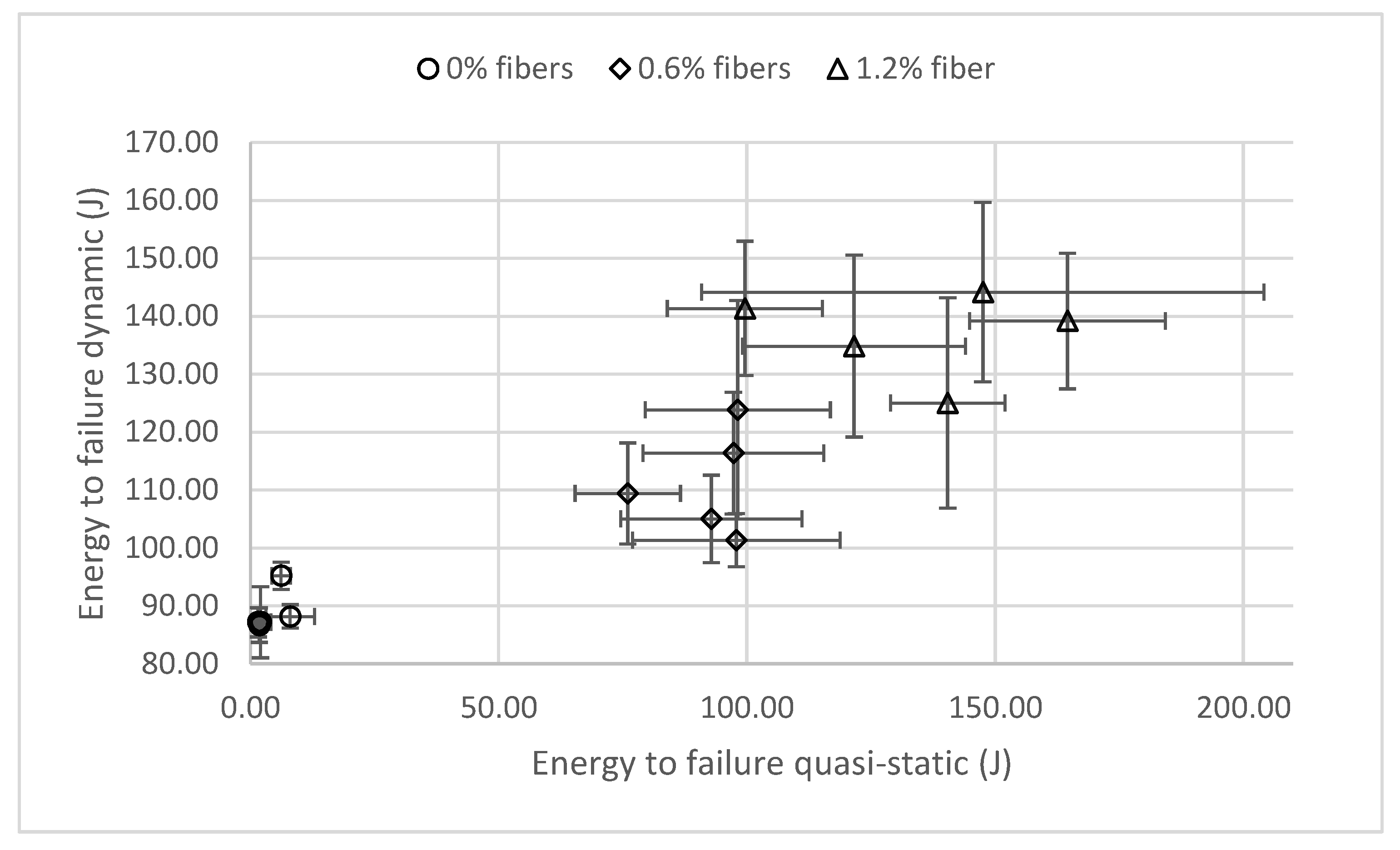

Dynamic vs. Quasi-Static

4. Conclusions

- Recycled tiers’ rubber aggregate contribution to energy absorption in bending load is negligible relative to the fiber contribution.

- The contribution of the fibers to the energy absorbance was not linear with fiber content. Doubling the fiber dose increased the energy absorbance less than the first dose.

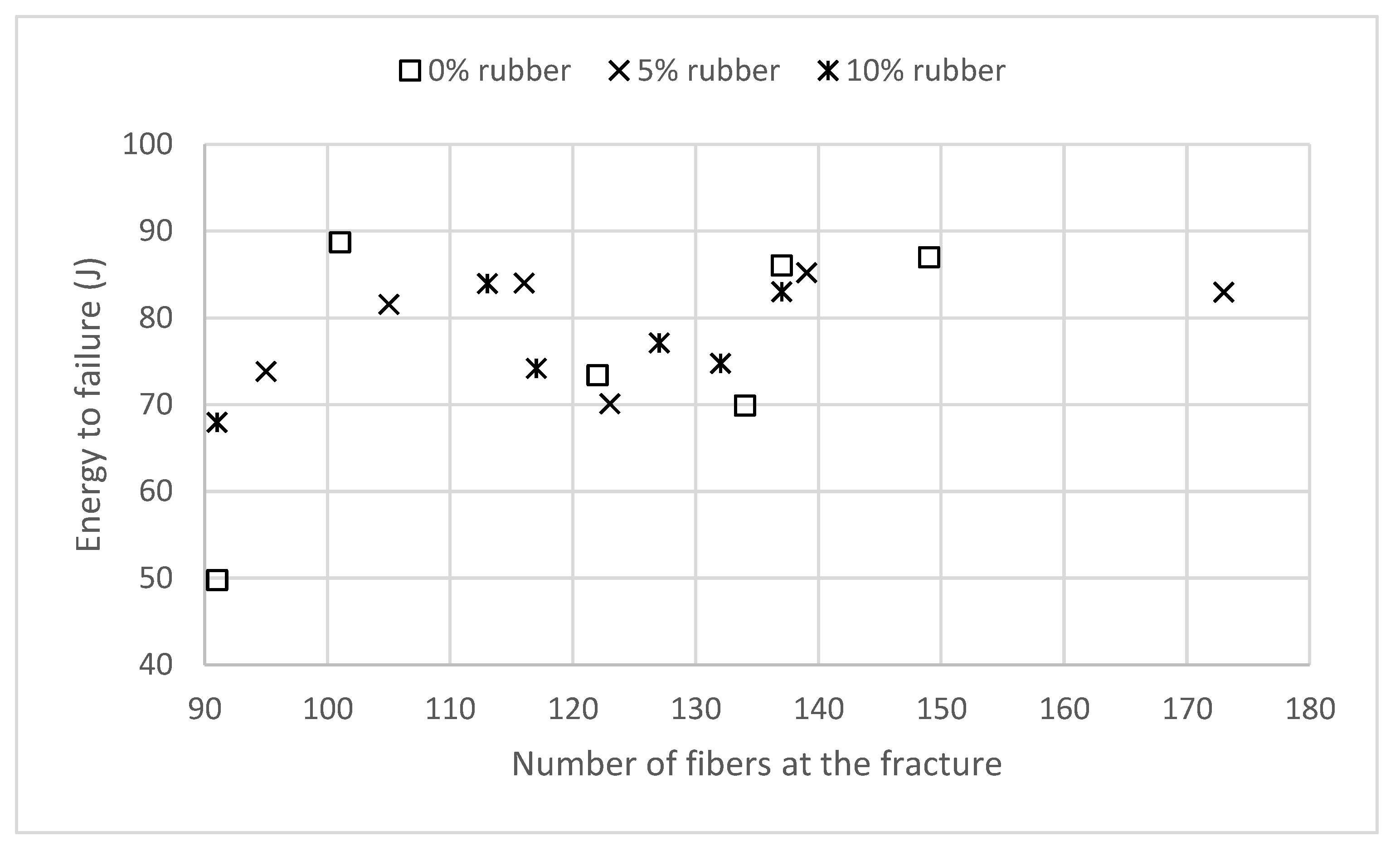

- The main factor contributing to the energy absorbance of fiber-reinforced beams was the number of fibers in the fracture surface. hence, the improvement of energy absorbance by fibers depends on its distribution in the concrete.

- The energy absorbance under dynamic load is higher than under quasi-static load. But, as the fiber content increased, the results became more similar. Therefore, a quasi-static test of fiber-reinforced concrete can be used to assess the fiber-reinforced concrete behavior under the impact load of a car crashing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Shojaati, Correlation between injury risk and impact severity index ASI, Swiss Transport Research Conference (2003).

- H.E.M. Sallam, A.S. Sherbini, M.H. Seleem, M.M. Balaha, IMPACT RESISTANCE OF RUBBERIZED CONCRETE, ERJ. Engineering Research Journal 31 (2008). [CrossRef]

- J.L. Lok Guan, Y.Y. Too, B.J.W. Teh, Y.J. Kum, Characterisation of Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete: Ductility and Service Life, CONSTRUCTION 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- T. Polydorou, K. Neocleous, R. Illampas, N. Kyriakides, A. Alsaif, C. Chrysostomou, K. Pilakoutas, D. Hadjimitsis, Steel fibre-reinforced rubberised concrete barriers as forgiving infrastructure, in: FIB 2018 - Proceedings for the 2018 Fib Congress: Better, Smarter, Stronger, 2019.

- L. Pan, H. Hao, J. Cui, T.M. Pham, Numerical study on impact resistance of rubberised concrete roadside barrier, Advances in Structural Engineering 26 (2023). [CrossRef]

- A.O. Atahan, U.K. Sevim, Testing and comparison of concrete barriers containing shredded waste tire chips, Mater Lett 62 (2008) 3754–3757. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Aiello, F. Leuzzi, Waste tyre rubberized concrete: Properties at fresh and hardened state, Waste Management 30 (2010) 1696–1704. [CrossRef]

- K.B. Najim, M.R. Hall, A review of the fresh/hardened properties and applications for plain- (PRC) and self-compacting rubberised concrete (SCRC), Constr Build Mater 24 (2010) 2043–2051. [CrossRef]

- V. Corinaldesi, J. Donnini, Waste rubber aggregates, in: New Trends in Eco-Efficient and Recycled Concrete, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N.F. Medina, R. Garcia, I. Hajirasouliha, K. Pilakoutas, M. Guadagnini, S. Raffoul, Composites with recycled rubber aggregates: Properties and opportunities in construction, Constr Build Mater 188 (2018). [CrossRef]

- M.M.R. Taha, A.S. El-Dieb, M.A.A. El-Wahab, M.E. Abdel-Hameed, Mechanical, Fracture, and Microstructural Investigations of Rubber Concrete, Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 20 (2008) 640–649.

- T.M. Pham, X. Zhang, M. Elchalakani, A. Karrech, H. Hao, A. Ryan, Dynamic response of rubberized concrete columns with and without FRP confinement subjected to lateral impact, Constr Build Mater 186 (2018). [CrossRef]

- A.M. Rashad, A comprehensive overview about recycling rubber as fine aggregate replacement in traditional cementitious materials, International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 5 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Y.C. Guo, J.H. Zhang, G. Chen, G.M. Chen, Z.H. Xie, Fracture behaviors of a new steel fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete with crumb rubber, Constr Build Mater 53 (2014) 32–39. [CrossRef]

- A.R. Khaloo, M. Dehestani, P. Rahmatabadi, Mechanical properties of concrete containing a high volume of tire-rubber particles, Waste Management 28 (2008) 2472–2482. [CrossRef]

- S.A.A. Gillani, M.R. Riaz, R. Hameed, A. Qamar, A. Toumi, A. Turatsinze, Fracture energy of fiber-reinforced and rubberized cement-based composites: A sustainable approach towards recycling of waste scrap tires, Energy and Environment (2022). [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Han, M. Chen, X. Wang, Z. Wang, T. Guo, Mechanical and stress-strain behavior of basalt fiber reinforced rubberized recycled coarse aggregate concrete, Constr Build Mater 260 (2020) 119888. [CrossRef]

- N. Segre, I. Joekes, A.D. Galves, J.A. Rodrigues, Rubber-mortar composites: Effect of composition on properties, J Mater Sci 39 (2004). [CrossRef]

- D. Cui, L. Wang, C. Zhang, H. Xue, D. Gao, F. Chen, Dynamic Splitting Performance and Energy Dissipation of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete under Impact Loading, Materials 17 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y.F. Li, G.K. Ramanathan, J.Y. Syu, C.H. Huang, Y.K. Tsai, Mechanical behavior of different fiber lengths mix-proportions carbon fiber reinforced concrete subjected to static, impact, and blast loading, International Journal of Protective Structures 15 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, H. Tu, Y. Li, Y. Weng, Effect of fiber content and fiber length on the dynamic compressive properties of strain-hardening ultra-high performance concrete, Constr Build Mater 328 (2022) 127024. [CrossRef]

- S. Yan, Q. Dong, X. Chen, J. Li, X. Wang, B. Shi, An experimental and numerical study on the hybrid effect of basalt fiber and polypropylene fiber on the impact toughness of fiber reinforced concrete, Constr Build Mater 411 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Mohamed, H. Elemam, M.H. Seleem, H.E.D.M. Sallam, Effect of fiber addition on strength and toughness of rubberized concretes, Sci Rep 14 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D.Y. Yoo, M.J. Kim, High energy absorbent ultra-high-performance concrete with hybrid steel and polyethylene fibers, Constr Build Mater 209 (2019). [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, X. Shi, S. Zhang, H. Chen, J. Zhou, Z. Yu, P. Huang, Fiber-reinforced cemented paste backfill: The effect of fiber on strength properties and estimation of strength using nonlinear models, Materials 13 (2020). [CrossRef]

- P. Konrád, R. Sovják, Energy-Based Approach for Studying Fibre-Reinforced Concrete Subjected to Impact Loading, Int J Concr Struct Mater 16 (2022) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- H. Taghipoor, A. Sadeghian, Experimental investigation of single and hybrid-fiber reinforced concrete under drop weight test, Structures 43 (2022). [CrossRef]

- H. Guo, C. Du, Y. Chen, D. Li, W. Hu, X. Lv, Study on protective performance of impact-resistant polyurea and its coated concrete under impact loading, Constr Build Mater 340 (2022) 127749. [CrossRef]

- J. Xie, J. Zhao, J. Wang, C. Fang, B. Yuan, Y. Wu, Impact behaviour of fly ash and slag-based geopolymeric concrete: The effects of recycled aggregate content, water-binder ratio and curing age, Constr Build Mater 331 (2022) 127359. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, H. Tu, Y. Li, Y. Weng, Effect of fiber content and fiber length on the dynamic compressive properties of strain-hardening ultra-high performance concrete, Constr Build Mater 328 (2022) 127024. [CrossRef]

- Y.B. Guo, G.F. Gao, L. Jing, V.P.W. Shim, Response of high-strength concrete to dynamic compressive loading, Int J Impact Eng 108 (2017) 114–135. [CrossRef]

- Y. Su, J. Li, C. Wu, P. Wu, Z.X. Li, Influences of nano-particles on dynamic strength of ultra-high performance concrete, Compos B Eng 91 (2016) 595–609. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hao, H. Hao, Dynamic compressive behaviour of spiral steel fibre reinforced concrete in split Hopkinson pressure bar tests, Constr Build Mater 48 (2013) 521–532. [CrossRef]

- H. Su, J. Xu, Dynamic compressive behavior of ceramic fiber reinforced concrete under impact load, Constr Build Mater 45 (2013) 306–313. [CrossRef]

- Y. Su, J. Li, C. Wu, P. Wu, Z.X. Li, Effects of steel fibres on dynamic strength of UHPC, Constr Build Mater 114 (2016) 708–718. [CrossRef]

- G. Gary, P. Bailly, Behaviour of a quasi-brittle material at high strain rate. Experiment and modelling Experiment and modelling, European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids 17 (1998) 403–420. [CrossRef]

- M.B. Shkolnikov, Strain rates in crashworthiness, Proceedings of 8th International LS-Dyna Users Conference, Troy, MI, USA (2004).

- W. Borkowski, Z. Hryciów, P. Rybak, J. Wysocki, Numerical simulation of the standard TB11 and TB32 tests for a concrete safety barrier, Journal of KONES Vol. 17, No. 4 (2010) 63–71.

- R.R. Neves, H. Fransplass, M. Langseth, L. Driemeier, M. Alves, Performance of Some Basic Types of Road Barriers Subjected to the Collision of a Light Vehicle, (n.d.).

- E. Ganjian, M. Khorami, A.A. Maghsoudi, Scrap-tyre-rubber replacement for aggregate and filler in concrete, Constr Build Mater 23 (2009) 1828–1836. [CrossRef]

- F. Liu, W. Zheng, L. Li, W. Feng, G. Ning, Mechanical and fatigue performance of rubber concrete, Constr Build Mater 47 (2013) 711–719. [CrossRef]

- S. Raffoul, R. Garcia, K. Pilakoutas, M. Guadagnini, N.F. Medina, Optimisation of rubberised concrete with high rubber content: An experimental investigation, Constr Build Mater 124 (2016). [CrossRef]

- A.O. Atahan, A.Ö. Yücel, Crumb rubber in concrete: Static and dynamic evaluation, Constr Build Mater 36 (2012) 617–622. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Aliabdo, A.E.M. Abd Elmoaty, M.M. Abdelbaset, Utilization of waste rubber in non-structural applications, Constr Build Mater 91 (2015) 195–207. [CrossRef]

- G. Girskas, D. Nagrockienė, Crushed rubber waste impact of concrete basic properties, Constr Build Mater 140 (2017) 36–42. [CrossRef]

- Marie, Zones of weakness of rubberized concrete behavior using the UPV, J Clean Prod 116 (2016) 217–222. [CrossRef]

- L. Lavagna, R. Nisticò, M. Sarasso, M. Pavese, An Analytical Mini-Review on the Compression Strength of Rubberized Concrete as a Function of the Amount of Recycled Tires Crumb Rubber, Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 1234 13 (2020) 1234. [CrossRef]

- M. Hsie, C. Tu, P.S. Song, Mechanical properties of polypropylene hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete, Materials Science and Engineering: A 494 (2008) 153–157. [CrossRef]

- X. Shi, P. Park, Y. Rew, K. Huang, C. Sim, Constitutive behaviors of steel fiber reinforced concrete under uniaxial compression and tension, Constr Build Mater 233 (2020) 117316. [CrossRef]

- LÖFGREN, Fibre-reinforced Concrete for Industrial Construction - - a fracture mechanics approach to material testing and structural analysis, CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, 2005.

- H.A. Toutanji, The use of rubber tire particles in concrete to replace mineral aggregates, Cem Concr Compos 18 (1996) 135–139. [CrossRef]

- H. Su, J. Yang, T.C. Ling, G.S. Ghataora, S. Dirar, Properties of concrete prepared with waste tyre rubber particles of uniform and varying sizes, J Clean Prod 91 (2015) 288–296. [CrossRef]

- K.B. Najim, M.R. Hall, Mechanical and dynamic properties of self-compacting crumb rubber modified concrete, Constr Build Mater 27 (2012) 521–530. [CrossRef]

- B.S. Thomas, R.C. Gupta, V. John Panicker, Experimental and modelling studies on high strength concrete containing waste tire rubber, Sustain Cities Soc 19 (2015) 68–73. [CrossRef]

- B.S. Thomas, R.C. Gupta, Long term behaviour of cement concrete containing discarded tire rubber, J Clean Prod 102 (2015) 78–87. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Al-Tayeb, B.H. Abu Bakar, H. Ismail, H. Md Akil, Effect of partial replacement of sand by fine crumb rubber on impact load behavior of concrete beam: Experiment and nonlinear dynamic analysis, Materials and Structures/Materiaux et Constructions 46 (2013) 1299–1307. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Al-Tayeb, B.H. Abu Bakar, H. Ismail, H.M. Akil, Effect of partial replacement of sand by recycled fine crumb rubber on the performance of hybrid rubberized-normal concrete under impact load: experiment and simulation, J Clean Prod 59 (2013) 284–289. [CrossRef]

- R. Yang, Y. Xu, P. Chen, J. Wang, Experimental study on dynamic mechanics and energy evolution of rubber concrete under cyclic impact loading and dynamic splitting tension, Constr Build Mater 262 (2020) 120071. [CrossRef]

- W. Feng, F. Liu, F. Yang, L. Jing, L. Li, H. Li, L. Chen, Compressive behaviour and fragment size distribution model for failure mode prediction of rubber concrete under impact loads, Constr Build Mater 273 (2021) 121767. [CrossRef]

- A.A.H. Beiram, H.M.K. Al-Mutairee, The effect of chip rubber on the properties of concrete, Mater Today Proc 60 (2022) 1981–1988. [CrossRef]

- I.B. Topçu, N. Avcular, Collision behaviours of rubberized concrete, Cem Concr Res 27 (1997) 1893–1898. [CrossRef]

- J.K. Huang, P.W. Jiang, Y. Di Qian, P. Cheng, R. Lou, X. Luo, Research on Mechanical Property and Impact Performance of Composite Rubber Hybrid Fiber Concrete, Arab J Sci Eng (2022) 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Senthil, A.P. Singh, Evaluation of concrete bricks with crumb rubber and polypropylene fibres under impact loading, Constr Build Mater 315 (2022) 125752. [CrossRef]

- F.M.Z. Hossain, M. Shahjalal, K. Islam, M. Tiznobaik, M.S. Alam, Mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete containing crumb rubber and polypropylene fiber, Constr Build Mater 225 (2019) 983–996. [CrossRef]

- Y. Geng, C.K.Y. Leung, A microstructural study of fibre/mortar interfaces during fibre debonding and pull-out, Journal of Materials Science 1996 31:5 31 (1996) 1285–1294. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L., Li, L. Shen, C.S. Poon, Compressive behaviour of recycled aggregate concrete under impact loading, Cem Concr Res (2015). [CrossRef]

- W. Li, Z. Luo, C. Long, C. Wu, W.H. Duan, S.P. Shah, Effects of nanoparticle on the dynamic behaviors of recycled aggregate concrete under impact loading, Mater Des (2016). [CrossRef]

| Aggregate name | Material | Grain size (mm) | Apparent specific gravity (SSD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine | Quartz | 0-4.75 | 2.62 |

| Medium | Dolomite | 9.5-14 | 2.641 |

| Coarse | Dolomite | 14-19 | 2.663 |

| Rubber | Rubber | 2.36-4.75 | 1.082 |

| Mix # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Fiber (%) | 0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| Cement | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 | 286 |

| Water | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Coarse | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 | 541 |

| Medium | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 | 272 |

| Fine | 958 | 942 | 927 | 831 | 815 | 800 | 704 | 689 | 673 | 577 | 562 | 546 | 450 | 435 | 420 |

| Rubber | 0 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 165 | 165 | 165 | 220 | 220 | 220 |

| Fibers | 0 | 5.5 | 11 | 0 | 5.5 | 11 | 0 | 5.5 | 11 | 0 | 5.5 | 11 | 0 | 5.5 | 11 |

| Antifoam agent | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).