Submitted:

16 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Sigmoid vaginoplasty has become a preferred technique for gender affirmation surgery in transgender women due to its ability to provide adequate vaginal width and depth, intrinsic mucosal lubrication, and resistance to postoperative shrinkage. However, despite its advantages, this technique is associated with rare but potentially severe complications, including neovaginal perforation. Objective: This review aims to comprehensively analyze neovaginal perforation following sigmoid vaginoplasty, highlighting its incidence, underlying mechanisms, clinical presentation, management strategies, and preventive measures. Methods: A systematic review of existing literature was conducted to evaluate reported cases of neovaginal perforation, its etiology, and treatment outcomes. Additionally, we present a representative case from our institution, providing further insights into the clinical course and management of this complication. Results: Neovaginal perforation, though uncommon, can lead to serious consequences such as abscess formation, peritonitis, and sepsis if not promptly diagnosed and treated. The primary contributing factors include improper postoperative vaginal dilation techniques, vascular compromise due to stenosis or ischemia, and tissue fragility of the sigmoid neovagina. Management strategies vary from conservative treatment with antibiotics and drainage to surgical intervention in severe cases. Conclusion: While sigmoid vaginoplasty remains a valuable technique for gender affirmation surgery, awareness of its potential complications—particularly neovaginal perforation—is crucial. Early recognition, appropriate management, and adherence to postoperative care protocols, including proper dilation techniques, are essential in preventing this rare but serious complication. A multidisciplinary approach involving plastic surgeons, colorectal surgeons, and gynecologists is key to optimizing patient outcomes and minimizing risks.

Keywords:

Introduction

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical Presentation and Case Reports

Reported Cases

- Liguori et al. (2001) documented a case of acute peritonitis secondary to introital stenosis, leading to perforation of a neovagina constructed from a bowel segment [16].

- Amirian et al. (2011) reported a patient who presented with lower abdominal pain and fever. CT imaging revealed free air in the retroperitoneum, and a leak through the vaginal apex was confirmed via vaginal contrast examination. This patient was successfully managed with conservative antibiotic therapy [17].

- Shimamura et al. (2015) described a case of neovaginal perforation complicated by an intra-abdominal abscess, where clinical symptoms and radiologic findings were incongruent. Surgical intraperitoneal drainage was performed due to concerns that the abscess might not resolve with antibiotics alone [15].

- Matthew et al. reported two cases involving diffuse stenosis of unknown etiology, leading to ischemia and subsequent perforation of the sigmoid conduit. One patient underwent midline laparotomy and was found to have multiple interloop abscesses, requiring prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy. The second patient, who developed vaginal stenosis secondary to a high-riding perineum, required laparoscopic sigmoid conduit resection, followed by a midline incision and internal suturing of the colon flap one month postoperatively [1].

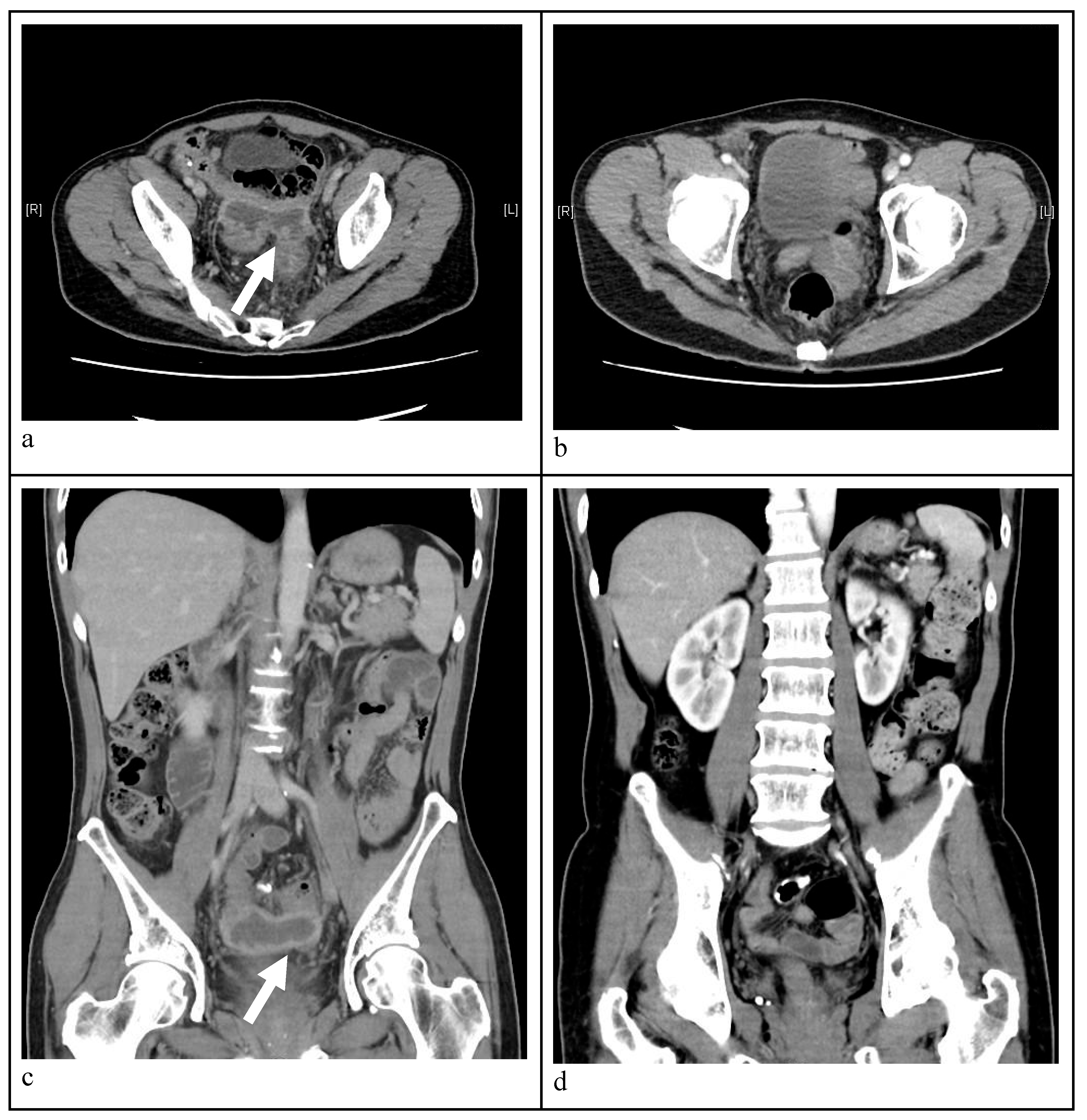

- Axial view CT image indicating a massive abscess occupying a significant portion of the intra-abdominal cavity. A well-circumscribed abscess fluid collection with enhanced walls is seen as pointed by the white arrows.

- Follow-up CT image disclosing no abscess and patent neovagina without perforation six months post-treatment.

- Sagittal view abdominal CT image demonstrating a intra-abdominal abscess. A well-circumscribed abscess fluid collection with enhanced walls is seen as pointed by the white arrow.

- Follow-up CT image disclosing no abscess and patent neovagina without perforation six months post-treatment.

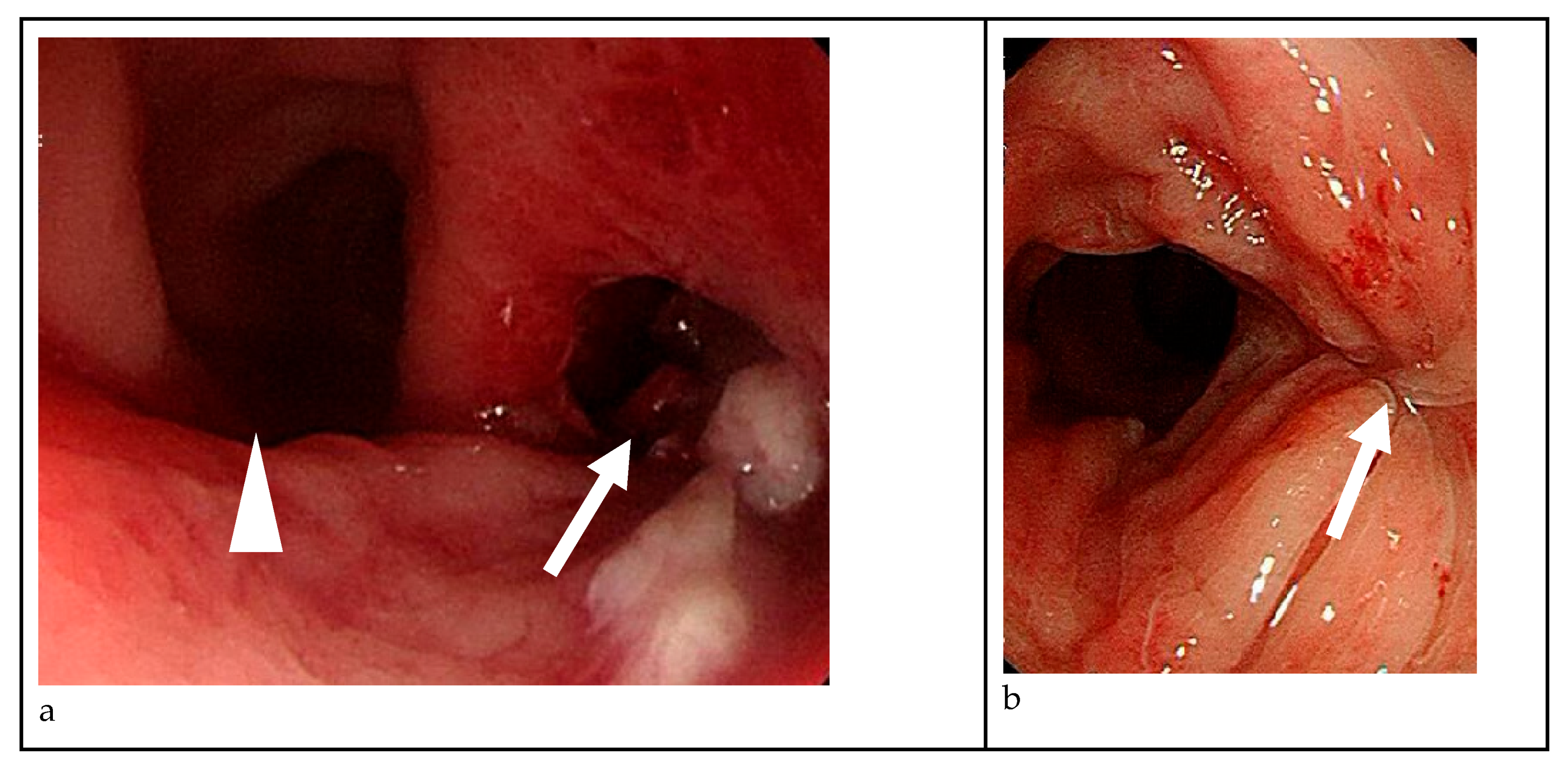

- On colonoscopy, a perforation was found at 10 cm level above vaginal orifice and in the 4-5 o'clock direction(white arrow), whereas the left-hand side lies the neovagina, as pointed by the white arrow head.

- The previous perforation site on the right-hand side was healed well and no further perforation was found after three months post-treatment, as pointed by the white arrows.

Diagnosis

Management Strategies

Future Directions

Conclusion

References

- Meece MS, Weber LE, Hernandez AE, Danker SJ, Paluvoi NV. Major complications of sigmoid vaginoplasty: a case series. J Surg Case Rep 2023;2023:rjad333. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin JF. XIV. The Formation of an Artificial Vagina by Intestinal Trransplantation. Ann Surg 1904;40:398–403.

- Salgado CJ, Nugent A, Kuhn J, Janette M, Bahna, H. Primary Sigmoid Vaginoplasty in Transwomen: Technique and Outcomes. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:4907208. [CrossRef]

- Hendren WH, Atala, A. Use of bowel for vaginal reconstruction. J Urol 1994;152:752–5; discussion 756–7. [CrossRef]

- Markland, C., Hastings D. Vaginal reconstruction using cecal and sigmoid bowel segments in transsexual patients. J Urol 1974;111:217–9. [CrossRef]

- Wedler V, Meuli-Simmen C, Guggenheim M, Schneller-Gustafsson, M., Künzi, W. Laparoscopic technique for secondary vaginoplasty in male to female transsexuals using a modified vascularized pedicled sigmoid. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2004;57:181–5. [CrossRef]

- Kim C, Campbell B, Ferrer, F. Robotic sigmoid vaginoplasty: a novel technique. Urology 2008;72:847–9. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik N, Jindal O, Bhardwaj DK. Sigma-lead male-to-female gender affirmation surgery: Blending cosmesis with functionality. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2019;7:e2169. [CrossRef]

- Nowier, A., Esmat M., Hamza RT. Surgical and functional outcomes of sigmoid vaginoplasty among patients with variants of disorders of sex development. Int Braz J Urol 2012;38:380–6;discussions387–8. [CrossRef]

- Kwun Kim S, Hoon Park J, Cheol Lee K, Min Park J, Tae Kim, J., Chan Kim, M. Long-term results in patients after rectosigmoid vaginoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;112:143–51. [CrossRef]

- Parsons JK, Gearhart SL, Gearhart JP. Vaginal reconstruction utilizing sigmoid colon: Complications and long-term results. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:629–33. [CrossRef]

- Tran S, Guillot-Tantay C, Sabbagh P, Vidart A, Bosset P-O., Lebret, T., et al. Systematic review of neovaginal prolapse after vaginoplasty in trans women. Eur Urol Open Sci 2024;66:101–11. [CrossRef]

- Bouman M-B, van Zeijl MCT, Buncamper ME, Meijerink WJHJ, van Bodegraven AA, Mullender MG. Intestinal vaginoplasty revisited: a review of surgical techniques, complications, and sexual function. J Sex Med 2014;11:1835–47. [CrossRef]

- Manrique OJ, Adabi K, Martinez-Jorge J, Ciudad P, Nicoli F, Kiranantawat, K. Complications and patient-reported outcomes in male-to-female vaginoplasty-where we are today: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Plast Surg 2018;80:684–91. [CrossRef]

- Shimamura Y, Fujikawa A, Kubota K, Ishii N, Fujita Y, Ohta, K. Perforation of the neovagina in a male-to-female transsexual: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2015;9:24. [CrossRef]

- Liguori G, Trombetta C, Buttazzi, L., Belgrano, E. Acute peritonitis due to introital stenosis and perforation of a bowel neovagina in a transsexual. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:828–9. [CrossRef]

- Amirian I, Gögenur I, Rosenberg, J. Conservatively treated perforation of the neovagina in a male to female transsexual patient. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:bcr0820103241–bcr0820103241. [CrossRef]

| 2001 Liguori et al. |

2011 Amirian et al. |

2015 Shimamura et al. |

2023 Matthew et al |

2023 Matthew et al. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early complication after surgery |

Total introital stenosis of the neovagina | no | Mild stenosis of the neovagina | Cellulitis and prolonged urinary retention on post-operative Days 19 and 20 |

Vaginal stenosis secondary to a high riding perineum |

| Symptom | Colicky abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and vomiting | Lower abdominal pain and fever | Persistent abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting | Abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, , large volume mucinous discharge, and an inability to dilate |

Abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting |

| Onset | 1 year post-operatively | Unknown | Unknown | 1 year post-operatively | 3 years post-operatively |

| Image findings | a large amount of fetid mucus in the abdominal cavity via laparoscopy |

|

CT: a massive abscess occupying a significant portion of the intra-abdominal cavity |

|

|

| Management | Exploratory laparotomy with primary repair | Intravenous antibiotics only | Exploratory laparotomy with primary repair | Midline laparotomy and resection of the necrotic sigmoid conduit | Laparoscopic resection of the sigmoid conduit |

| Prognosis | Recurrent total stenosis of the neovaginal introitus | Fair and no complications noted | No complications related to the surgery | Without further complication | Without further complication |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).