Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Data Set

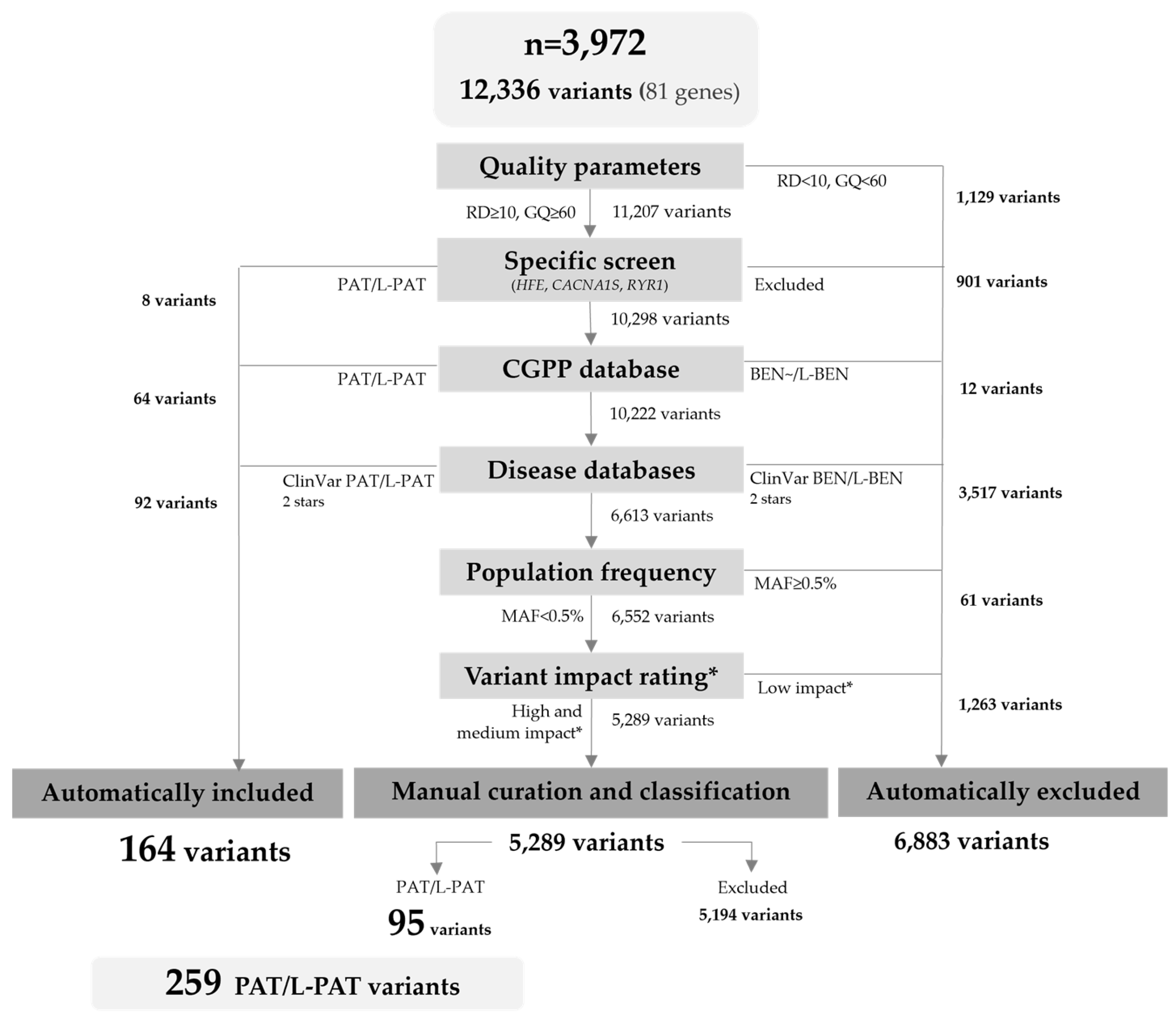

2.2. Variant Filtering and Curation

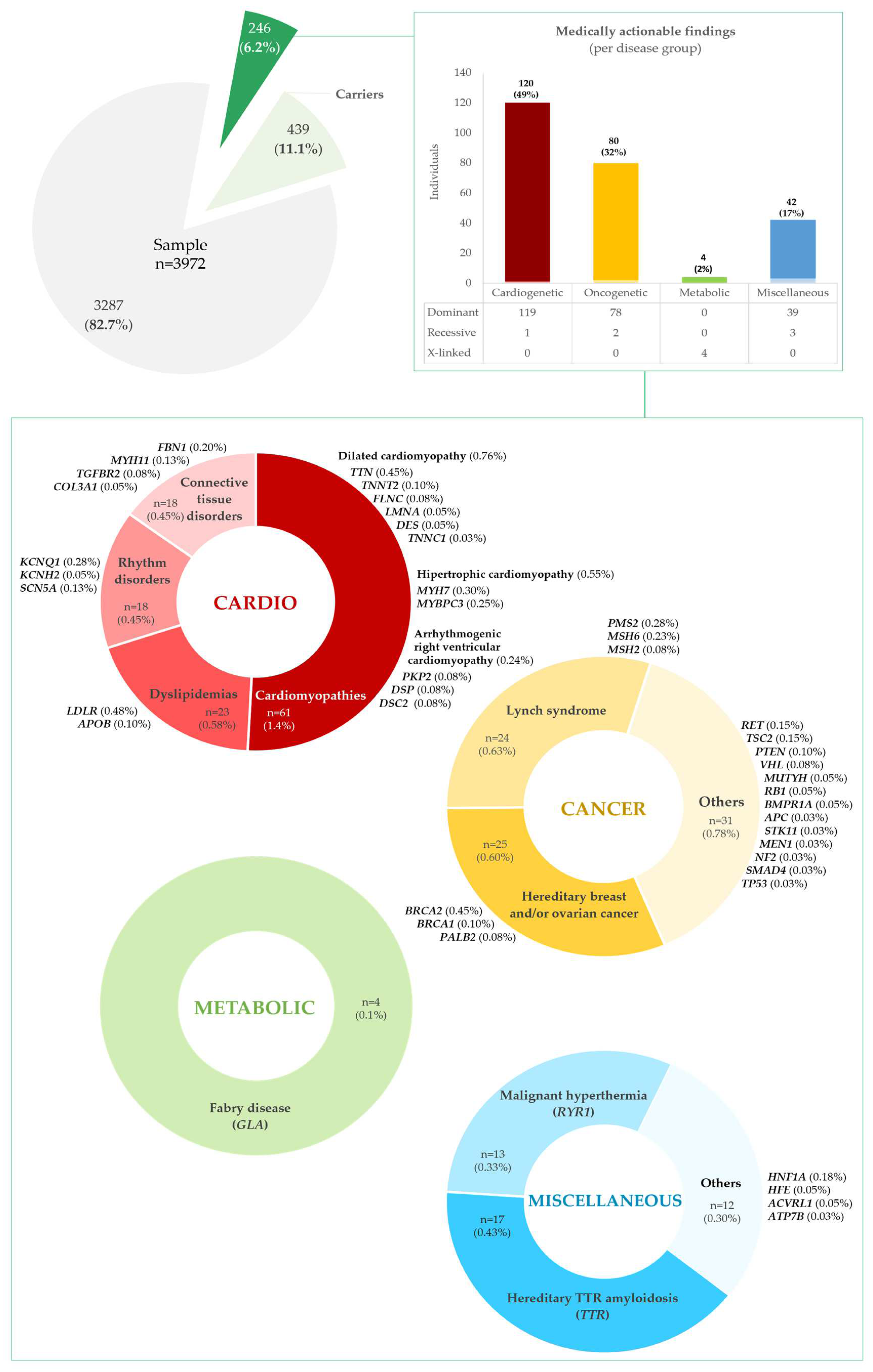

2.3. Medically Actionable Findings and Carriers

2.3.1. Frequency of Medically Actionable Findings

| Disease | Gene |

Disease Inheritance |

Nr. of variants per gene | Allele count | Allelic frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Hom. | Het. | |||||

| Cancer phenotype group | |||||||

| Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) | APC | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 |

| Familial medullary thyroid cancer | RET | AD | 3 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0.076 |

| Hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer | BRCA1 | AD | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 |

| BRCA2 | AD | 16 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0.227 | |

| PALB2 | AD | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.050 | |

| Hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndrome | SDHD | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 |

| SDHAF2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |

| SDHC | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |

| SDHB | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |

| MAX | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |

| TMEM127 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |

| Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) | BMPR1A | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 |

| Juvenile polyposis syndrome / hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia syndrome | SMAD4 | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 |

| Li–Fraumeni syndrome | TP53 | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 |

| Disease | Gene |

Disease Inheritance |

Nr. of variants per gene | Allele count | Allelic frequency (%) | |||||||

| Total | Hom. | Het. | ||||||||||

| Lynch syndrome (HNPCC) | MLH1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| MSH2 | AD | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.050 | ||||||

| MSH6 | AD | 8 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0.113 | ||||||

| PMS2 | AD | 6 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0.138 | ||||||

| Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 | MEN1 | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 | |||||

| MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) | MUTYH | AR | 17 | 95 | 4 | 91 | 1.196 | |||||

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | NF2 | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 | |||||

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) | STK11 | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 | |||||

| PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome | PTEN | AD | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.050 | |||||

| Retinoblastoma | RB1 | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 | |||||

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | TSC1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| TSC2 | AD | 6 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0.076 | ||||||

| von Hippel-Lindau syndrome | VHL | AD | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 | |||||

| WT1-related Wilms tumor | WT1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| Cardiovascular phenotype group | ||||||||||||

| Aortopathies | FBN1 | AD | 8 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0.101 | |||||

| TGFBR1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| TGFBR2 | AD | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 | ||||||

| SMAD3 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| ACTA2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| MYH11 | AD | 3 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.063 | ||||||

| Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (a subcategory of ACM) | PKP2 | AD | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 | |||||

| DSP | AD | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 | ||||||

| DSC2 | AD | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 | ||||||

| TMEM43 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| DSG2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia | RYR2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| CASQ2 | AR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| TRDN | AR | 6 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0.151 | ||||||

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | TNNT2 | AD | 3 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.050 | |||||

| LMNA | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 | ||||||

| FLNC | AD | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.038 | ||||||

| TTN | AD | 18 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0.227 | ||||||

| BAG3 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| DES | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 | ||||||

| RBM20 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| TNNC1 | AD | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.013 | ||||||

| Disease | Gene |

Disease Inheritance |

Nr. of variants per gene | Allele count | Allelic frequency (%) | |||||||

| Total | Hom. | Het. | ||||||||||

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. vascular type | COL3A1 | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 | |||||

| Familial hypercholesterolemia | LDLR | AD | 15 | 19 | 0 | 19 | 0.239 | |||||

| APOB | AD | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.050 | ||||||

| PCSK9 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | MYH7 | AD | 8 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0.151 | |||||

| MYBPC3 | AD | 10 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0.126 | ||||||

| TNNI3 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| TPM1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| MYL3 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| ACTC1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| PRKAG2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| MYL2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Long QT syndrome types 1 and 2 | KCNQ1 | AD | 6 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 0.151 | |||||

| KCNH2 | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 | ||||||

| Long QT syndrome 3. Brugada syndrome | SCN5A | AD | 4 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.063 | |||||

| Long QT syndrome types 14-16 | CALM1 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| CALM2 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| CALM3 | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Inborn errors of metabolism phenotype group | ||||||||||||

| Biotinidase deficiency | BTD | AR | 10 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0.189 | |||||

| Fabry disease | GLA | XL | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0.063 | |||||

| Pompe disease | GAA | AR | 9 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 0.252 | |||||

| Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency | OTC | XL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | |||||

| Miscellaneous phenotype group | ||||||||||||

| Hereditary hemochromatosis | HFE | AR | 1 | 211 | 4 | 207 | 2.656 | |||||

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | ACVRL1 | AD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.025 | |||||

| ENG | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Malignant hyperthermia | RYR1 | AD | 7 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 0.164 | |||||

| CACNA1S | AD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Maturity-onset of diabetes of the young | HNF1A | AD | 3 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0.088 | |||||

| RPE65-related retinopathy | RPE65 | AR | 11 | 21 | 0 | 21 | 0.264 | |||||

| Wilson disease | ATP7B | AR | 24 | 75 | 2 | 73 | 0.944 | |||||

| Hereditary TTR-related amyloidosis | TTR | AD | 2 | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0.214 | |||||

2.3.2. Carrier Frequencies

2.3.3. Novel Variant Findings

| Gene |

cDNA (HGVS) |

Predicted Splicing Impact (Y / N) |

Protein change (HGVS) |

Freq. (gnomAD 4.1) (%) |

ClinVar ID (2025-01-02) |

||

| BMPR1A | NM_004329.3:c.231-2A>T | Y | - | - | 2866138 | ||

| NM_004329.3:c.231-1G>T | Y | - | - | 567998 | |||

| BRCA1 | NM_007294.4:c.109A>G | N | NP_009225.1:p.Thr37Ala | - | 868146 | ||

| BRCA2 | NM_000059.4:c.2974A>T | N | NP_000050.3:p.Lys992* | - | - | ||

| NM_000059.4:c.4933A>T | N | NP_000050.3:p.Lys1645* | - | 51744 | |||

| NM_000059.4:c.7258delG | N | NP_000050.3:p.Glu2420Asnfs*47 | - | - | |||

| MEN1 | NM_130799.3:c.467G>C | N | NP_570711.2:p.Gly156Ala | - | - | ||

| MSH2 | NM_000251.3:c.2084T>G | N | NP_000242.1:p.Val695Gly | - | - | ||

| MSH6 | NM_000179.3:c.195_199delACCGC | N | NP_000170.1:p.Pro66Glnfs*22 | 0.0001 | - | ||

| NM_000179.3:c.198_199insTT | N | NP_000170.1:p.Pro67Phefs*15 | - | - | |||

| NM_000179.3:c.841G>T | N | NP_000170.1:p.Gly281* | - | 2673649 | |||

| NM_000179.3:c.2437A>T | N | NP_000170.1:p.Lys813* | 0.0001 | 1791241 | |||

| NM_000179.3:c.3682_3698del | N | NP_000170.1:p.Ala1228Argfs*4 | - | - | |||

| MUTYH | NM_001128425.2:c.788+2_788+4delTAG | Y | - | - | - | ||

| NM_001128425.2:c.785_786insG | N | NP_001121897.1:p.Trp263Leufs*66 | - | - | |||

| NM_001128425.2:c.781delC | N | NP_001121897.1:p.Gln261Serfs*5 | - | - | |||

| Gene |

cDNA (HGVS) |

Predicted Splicing Impact (Y / N |

Protein change (HGVS) |

Freq. (gnomAD 4.1) (%) |

ClinVar ID (2025-01-02) |

| PTEN | NM_000314.8:c.802-1_805delGGACA | N | NP_000305.3:p.? | - | - |

| NM_000314.8:c.804_805insTTTTT | N | NP_000305.3:p.Lys269Phefs*9 | - | - | |

| RB1 | NM_000321.3:c.1422-2A>T | Y | - | 0.0004 | - |

| SMAD4 | NM_005359.6:c.904+1_904+2ins(45) | Y | - | 0.0053 | - |

| TSC2 | NM_000548.5:c.264_265delGT | N | NP_000539.2:p.Leu89Alafs*36 | 0.0160 | 45485999 |

| NM_000548.5:c.340G>T | N | NP_000539.2:p.Glu114* | - | 65033 | |

| NM_000548.5:c.775-2A>C | Y | - | - | - | |

| NM_000548.5:c.2340_2341ins(37) | N | NP_000539.2:p.Asp781Phefs*12 | - | - | |

| APOB | NM_000384.3:c.9743_9744insG | N | NP_000375.3:p.Ile3248Metfs*12 | - | - |

| NM_000384.3:c.9735delC | N | NP_000375.3:p.Gln3247Lysfs*19 | - | - | |

| NM_000384.3:c.2297_2298delAA | N | NP_000375.3:p.Lys766Ilefs*25 | - | 1553385715 | |

| COL3A1 | NM_000090.4:c.1429G>A | N | NP_000081.2:p.Gly477Arg | - | - |

| NM_000090.4:c.2229+1G>A | Y | - | - | 640856 | |

| DES | NM_001927.4:c.75_76insAG | N | NP_001918.3:p.Leu26Serfs*6 | - | - |

| DSC2 | NM_024422.6:c.1044_1047dupAAAT | N | NP_077740.1:p.Asp350Lysfs*2 | - | - |

| NM_024422.6:c.631-1G>A | Y | - | 0.0001 | 2775190 | |

| DSP | NM_004415.4:c.107delG | N | NP_004406.2:p.Gly36Alafs*12 | - | - |

| NM_004415.4:c.1258G>T | N | NP_004406.2:p.Glu420* | - | - | |

| NM_004415.4:c.2572delG | N | NP_004406.2:p.Glu858Lysfs*6 | - | - | |

| FBN1 | NM_000138.5:c.4282C>T | N | NP_000129.3:p.Arg1428Cys | 0.0007 | - |

| NM_000138.5:c.4015_4016insTG | N | NP_000129.3:p.Cys1339Leufs*75 | - | - | |

| FLNC | NM_001458.5:c.502delT | N | NP_001449.3:p.Trp168Glyfs*84 | - | - |

| NM_001458.5:c.2550+1G>A | Y | - | - | - | |

| KCNH2 | NM_000238.4:c.1621C>T | N | NP_000229.1:p.Arg541Cys | 0.0004 | 937094 |

| LDLR | NM_000527.5:c.1315A>T | N | NP_000518.1:p.Asn439Tyr | - | 375813 |

| MYBPC3 | NM_000256.3:c.2995-2A>G | Y | - | 0.0001 | - |

| MYH7 | NM_000257.4:c.1756G>A | N | NP_000248.2:p.Val586Met | 0.0004 | 1172186 |

| PKP2 | NM_004572.4:c.1489C>T | N | NP_004563.2:p.Arg497* | 0.0003 | 78974 |

| NM_004572.4:c.328delA | N | NP_004563.2:p.Met110Cysfs*2 | - | - | |

| SCN5A | NM_198056.3:c.5306C>T | N | NP_932173.1:p.Ala1769Val | 0.0001 | - |

| TGFBR2 | NM_003242.6:c.760C>T | N | NP_001020018.1:p.Arg279Cys | 0.0001 | 213942 |

| TNNT2 | NM_001276345.2:c.87_88delGG | N | NP_001263274.1:p.Asp30Argfs*13 | - | - |

| NM_001276345.2:c.80G>A | N | NP_001263274.1:p.Trp27* | - | - | |

| Gene |

cDNA (HGVS) |

Predicted Splicing Impact (Y / N |

Protein change (HGVS) |

Freq. (gnomAD 4.1) (%) |

ClinVar ID (2025-01-02) |

| TRDN | NM_006073.4:c.1831+1G>A | Y | - | - | - |

| NM_006073.4:c.1155delA | N | NP_006064.2:p.Lys385Asnfs*5 | 0.0013 | - | |

| NM_001256021.2:c.601_610delCTGGCGAAAG | N | NP_001242950.1:p.Leu201Asnfs*19 | 0.0029 | - | |

| NM_001256021.2:c.439_440delAA | N | NP_001242950.1:p.Lys147Aspfs*2 | 0.0001 | 2114339116 | |

| TTN | NM_001267550.2:c.107409_107410insCC | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Leu35804Profs*2 | - | - |

| NM_001267550.2:c.97573_97574insTC | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Asp32525Valfs*8 | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.95576_95577delAA | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Lys31859Argfs*6 | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.93623_93626dupAGCC | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Gln31210Alafs*8 | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.84525G>A | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Trp28175* | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.79811dupT | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Arg26605Lysfs*19 | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.70971_70972insT | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Leu23658Serfs*18 | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.64266delA | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Asp21423Ilefs*2 | 0.0001 | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.58709C>G | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Ser19570* | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.52975_52976delCA | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Gln17659Thrfs*6 | 0.0001 | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.41845dupA | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Ile13949Asnfs*2 | - | - | |

| NM_001267550.2:c.13184delT | N | NP_001254479.2:p.Leu4395Argfs*25 | - | - | |

| ACVRL1 | NM_000020.3:c.830C>T | N | NP_000011.2:p.Thr277Met | 0.0004 | 2731545 |

| ATP7B | NM_000053.4:c.3959G>C | N | NP_000044.2:p.Arg1320Thr | 0.0010 | 1479012 |

| RPE65 | NM_000329.3:c.1544G>A | N | NP_000320.1:p.Arg515Gln | 0.0015 | 1052287 |

3. Discussion

- Lab cohort bias. Our sample was derived from cases ascertained for genetic diagnosis of various Mendelian disorders; therefore, a few persons in the cohort may already be affected by a disease attributable to one of the genes in the ACMG list. Despite this, when excluding L-PAT/PAT variants listed as primary diagnosis in the genetic test reports of these patients, the overall frequency did not differ significantly (only 0.6%);

- Gene list. We limited our analysis to the current set of the ACMG genes. We did not consider other clinically relevant genes, as those curated by the ClinGen Actionability Working Group, for instance. Inclusion of additional conditions, some of specific impact in the Portuguese population, should be considered in future studies, what might increase the overall frequency of actionable findings;

- Study design. In order to minimize impact of data used, our project protocol prevented us from including individual-level information regarding ethnic background, age, gender, reason for referral for WES, or phenotype. Additionally, genotypes obtained were related to the whole cohort, not the patient. Consequently, we were not able to estimate compound heterozygosity, or the number of findings per individual;

- Technical limitations. Methodologies used may have led to missed variants due to: (i) intrinsic WES limitation to detect deep intronic, triplet repeats expansion, and structural variants; (ii) use of different capture kits along time within this cohort; (iii) incomplete coverage in some regions; (iv) not considering structural variants, including copy number variants (CNVs); and (v) MAF cut-off;

- Potential for false-positive interpretation of variants. Variants accurately classified as PAT/L-PAT, based on available evidence, may not be in fact disease causing, due to incomplete penetrance or variable expressivity. This is exacerbated when genetic testing is performed in the context of population screening;

- Actionability. The term “actionable” is highly subjective and its application may fluctuate. The ClinGen Actionability Working Group is addressing this issue by curating the actionability of several gene-disease groups, including those listed by the ACMG. We took this into consideration; however, some gene-disease groups are not yet curated and others are classified as actionable depending on individual-level information, such as age and sex, which were not considered due to our study protocol.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Data Set of Exomes

4.2. Resampling from CGPP-IBMC Clinical Database

4.3. Selection of Genes for Which Reporting of Secondary Findings Are Recommended

4.4. Data Processing

4.5. Variant Annotation

4.6. Variant Filtering

4.7. Manual Variant Curation, Classification, and Actionability

4.8. Frequency of Actionable Findings Calculation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, R.C.; Berg, J.S.; Grody, W.W.; Kalia, S.S.; Korf, B.R.; Martin, C.L.; McGuire, A.L.; Nussbaum, R.L.; O’Daniel, J.M.; Ormond, K.E.; et al. ACMG Recommendations for Reporting of Incidental Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing. Genet. Med. 2013, 15, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.S.; Adelman, K.; Bale, S.J.; Chung, W.K.; Eng, C.; Evans, J.P.; Herman, G.E.; Hufnagel, S.B.; Klein, T.E.; Korf, B.R.; et al. Recommendations for Reporting of Secondary Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing, 2016 Update (ACMG SF v2.0): A Policy Statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesecker, L.G. ACMG Secondary Findings 2.0. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Gordon, A.S.; Amendola, L.M.; Adelman, K.; Bale, S.J.; Chung, W.K.; Gollob, M.H.; Harrison, S.M.; Herman, G.E.; et al. Recommendations for Reporting of Secondary Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing, 2021 Update: A Policy Statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Chung, W.K.; Gordon, A.S.; Herman, G.E.; Klein, T.E.; Stewart, D.R.; Amendola, L.M.; Adelman, K.; Bale, S.J.; et al. ACMG SF v3.0 List for Reporting of Secondary Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing: A Policy Statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Abul-Husn, N.S.; Amendola, L.M.; Brothers, K.; Chung, W.K.; Gollob, M.H.; Gordon, A.S.; Harrison, S.M.; Hershberger, R.E.; et al. ACMG SF v3.1 List for Reporting of Secondary Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing: A Policy Statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.T.; Lee, K.; Abul-Husn, N.S.; Amendola, L.M.; Brothers, K.; Chung, W.K.; Gollob, M.H.; Gordon, A.S.; Harrison, S.M.; Hershberger, R.E.; et al. ACMG SF v3.2 List for Reporting of Secondary Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing: A Policy Statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genetics in Medicine 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van El, C.G.; Cornel, M.C.; Borry, P.; Hastings, R.J.; Fellmann, F.; Hodgson, S.V.; Howard, H.C.; Cambon-Thomsen, A.; Knoppers, B.M.; Meijers-Heijboer, H.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing in Health Care. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wert, G.; Dondorp, W.; Clarke, A.; Dequeker, E.M.C.; Cordier, C.; Deans, Z.; van El, C.G.; Fellmann, F.; Hastings, R.; Hentze, S.; et al. Opportunistic Genomic Screening. Recommendations of the European Society of Human Genetics. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 29, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfatih, A.; Mohammed, I.; Abdelrahman, D.; Mifsud, B. Frequency and Management of Medically Actionable Incidental Findings from Genome and Exome Sequencing Data: A Systematic Review. Physiol Genom. 2021, 53, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorschner, M.O.; Amendola, L.M.; Turner, E.H.; Robertson, P.D.; Shirts, B.H.; Gallego, C.J.; Bennett, R.L.; Jones, K.L.; Tokita, M.J.; Bennett, J.T.; et al. Actionable, Pathogenic Incidental Findings in 1,000 Participants’ Exomes. Am J Hum Genet 2013, 93, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, L.; Sincan, M.; Markello, T.; Adams, D.R.; Gill, F.; Godfrey, R.; Golas, G.; Groden, C.; Landis, D.; Nehrebecky, M.; et al. The Implications of Familial Incidental Findings from Exome Sequencing: The NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program Experience. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, L.M.; Dorschner, M.O.; Robertson, P.D.; Salama, J.S.; Hart, R.; Shirts, B.H.; Murray, M.L.; Tokita, M.J.; Gallego, C.J.; Kim, D.S.; et al. Actionable Exomic Incidental Findings in 6503 Participants: Challenges of Variant Classification. Genome Res 2015, 25, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfson, E.; Cottrell, C.E.; Davidson, N.O.; Gurnett, C.A.; Heusel, J.W.; Stitziel, N.O.; Chen, L.S.; Hartz, S.; Nagarajan, R.; Saccone, N.L.; et al. Identification of Medically Actionable Secondary Findings in the 1000 Genomes. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Muzny, D.M.; Xia, F.; Niu, Z.; Person, R.; Ding, Y.; Ward, P.; Braxton, A.; Wang, M.; Buhay, C.; et al. Molecular Findings among Patients Referred for Clinical Whole-Exome Sequencing. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014, 312, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, F.E.; Murray, M.F.; Overton, J.D.; Habegger, L.; Leader, J.B.; Fetterolf, S.N.; O’Dushlaine, C.; Van Hout, C.V.; Staples, J.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, C.; et al. Distribution and Clinical Impact of Functional Variants in 50,726 Whole-Exome Sequences from the DiscovEHR Study. Science (1979) 2016, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, J.; Ling, H.; Hetrick, K.; Pugh, E.; Schiettecatte, F.; Doheny, K.; Hamosh, A.; Avramopoulos, D.; Valle, D.; Sobreira, N. Assessment of Incidental Findings in 232 Whole-Exome Sequences from the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K.A.; Gonzaga-Jauregui, C.; Brigatti, K.W.; Williams, K.B.; King, A.K.; Van Hout, C.; Robinson, D.L.; Young, M.; Praveen, K.; Heaps, A.D.; et al. Genomic Diagnostics within a Medically Underserved Population: Efficacy and Implications. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Gandhi, S.; Koshy, R.; Scaria, V. Incidental and Clinically Actionable Genetic Variants in 1005 Whole Exomes and Genomes from Qatar. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2018, 293, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, S.; Dagan-Rosenfeld, O.; Zhou, W.; Reza Sailani, M.; Limcaoco, P.; Colbert, E.; Avina, M.; Wheeler, J.; Craig, C.; Salins, D.; et al. High-Frequency Actionable Pathogenic Exome Variants in an Average-Risk Cohort. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S. man; Dattani, S.; So, M. ting; Cherny, S.S.; Tam, P.K.H.; Sham, P.C.; Garcia-Barcelo, M.M. Actionable Secondary Findings from Whole-Genome Sequencing of 954 East Asians. Hum Genet 2018, 137, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.L.; Finnila, C.R.; Bowling, K.M.; Brothers, K.B.; Neu, M.B.; Amaral, M.D.; Hiatt, S.M.; East, K.M.; Gray, D.E.; Lawlor, J.M.J.; et al. Genomic Sequencing Identifies Secondary Findings in a Cohort of Parent Study Participants. Genet. Med. 2018, 20, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yehia, L.; Ni, Y.; Sesock, K.; Niazi, F.; Fletcher, B.; Chen, H.J.L.; LaFramboise, T.; Eng, C. Unexpected Cancer-Predisposition Gene Variants in Cowden Syndrome and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba Syndrome Patients without Underlying Germline PTEN Mutations. PLoS Genet 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haer-Wigman, L.; van der Schoot, V.; Feenstra, I.; Vulto-van Silfhout, A.T.; Gilissen, C.; Brunner, H.G.; Vissers, L.E.L.M.; Yntema, H.G. 1 in 38 Individuals at Risk of a Dominant Medically Actionable Disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragan Hart, M.; Biesecker, B.B.; Blout, C.L.; Christensen, K.D.; Amendola, L.M.; Bergstrom, K.L.; Biswas, S.; Bowling, K.M.; Brothers, K.B.; Conlin, L.K.; et al. Secondary Findings from Clinical Genomic Sequencing: Prevalence, Patient Perspectives, Family History Assessment, and Health-Care Costs from a Multisite Study. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, K.A.; White, M.; Allen, N.M.; Byrne, S.; Carton, R.; Comerford, E.; Costello, D.; Doherty, C.; Dunleavey, B.; El-Naggar, H.; et al. A Comparison of Genomic Diagnostics in Adults and Children with Epilepsy and Comorbid Intellectual Disability. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 1066–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkh, N.; Mehawej, C.; Chouery, E. Actionable Exomic Secondary Findings in 280 Lebanese Participants. Front Genet 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.W.; Hwu, W.L.; Chien, Y.H.; Hsu, C.; Hung, M.Z.; Lin, I.L.; Lai, F.; Lee, N.C. Frequency and Spectrum of Actionable Pathogenic Secondary Findings in Taiwanese Exomes. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, J.; Arp, P.; Broer, L.; Verlouw, J.; Van Rooij, F.; Kraaij, R.; Uitterlinden, A.; Verkerk, A.J.M.H. Reduced Penetrance of Pathogenic ACMG Variants in a Deeply Phenotyped Cohort Study and Evaluation of ClinVar Classification over Time. Genetics in Medicine 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.H.; Chae, J.; Choi, S.; Kim, M.J.; Choi, M.; Chae, J.H.; Cho, E.H.; Hwang, T.J.; Jang, S.S.; Kim, J. Il; et al. Findings of a 1303 Korean Whole-Exome Sequencing Study. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi-Kabata, Y.; Yasuda, J.; Tanabe, O.; Suzuki, Y.; Kawame, H.; Fuse, N.; Nagasaki, M.; Kawai, Y.; Kojima, K.; Katsuoka, F.; et al. Evaluation of Reported Pathogenic Variants and Their Frequencies in a Japanese Population Based on a Whole-Genome Reference Panel of 2049 Individuals Article. J Hum Genet 2018, 63, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.S.; Zouk, H.; Venner, E.; Eng, C.M.; Funke, B.H.; Amendola, L.M.; Carrell, D.S.; Chisholm, R.L.; Chung, W.K.; Denny, J.C.; et al. Frequency of Genomic Secondary Findings among 21,915 EMERGE Network Participants. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan Ateş, E.; Türkyilmaz, A.; Yıldırım, Ö.; Alavanda, C.; Polat, H.; Demir, Ş.; Çebi, A.H.; Geçkinli, B.B.; Güney, A.İ.; Ata, P.; et al. Secondary Findings in 622 Turkish Clinical Exome Sequencing Data. J Hum Genet 2021, 66, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfatih, A.; Mifsud, B.; Syed, N.; Badii, R.; Mbarek, H.; Abbaszadeh, F.; Estivill, X.; Ismail, S.; Al-Muftah, W.; Badji, R.; et al. Actionable Genomic Variants in 6045 Participants from the Qatar Genome Program. Hum Mutat 2021, 42, 1584–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schoot, V.; Haer-Wigman, L.; Feenstra, I.; Tammer, F.; Oerlemans, A.J.M.; van Koolwijk, M.P.A.; van Agt, F.; Arens, Y.H.J.M.; Brunner, H.G.; Vissers, L.E.L.M.; et al. Lessons Learned from Unsolicited Findings in Clinical Exome Sequencing of 16,482 Individuals. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Salgado, L.E.; Silva-Aldana, C.T.; Medina-Méndez, E.; Bareño-Silva, J.; Arcos-Burgos, M.; Silgado-Guzmán, D.F.; Restrepo, C.M. Frequency of Actionable Exomic Secondary Findings in 160 Colombian Patients: Impact in the Healthcare System. Gene 2022, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, B.; Shi, J.; Zhao, S.; Xu, K.; Sun, L.; Chen, N.; Tian, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, N. Landscape of Secondary Findings in Chinese Population: A Practice of ACMG SF v3.0 List. 0 List. J Pers Med 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martone, S.; Buonagura, A.T.; Marra, R.; Rosato, B.E.; Del Giudice, F.; Bonfiglio, F.; Capasso, M.; Iolascon, A.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R. Clinical Exome-Based Panel Testing for Medically Actionable Secondary Findings in a Cohort of 383 Italian Participants. Front Genet 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasak, L.; Lillepea, K.; Nagirnaja, L.; Aston, K.I.; Schlegel, P.N.; Gonçalves, J.; Carvalho, F.; Moreno-Mendoza, D.; Almstrup, K.; Eisenberg, M.L.; et al. Actionable Secondary Findings Following Exome Sequencing of 836 Non-Obstructive Azoospermia Cases and Their Value in Patient Management. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 1652–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershberger, R.E.; Morales, A.; Siegfried, J.D. Clinical and Genetic Issues in Dilated Cardiomyopathy: A Review for Genetics Professionals. Genet. Med. 2010, 12, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, B.; Gardin, J.; Flack, J.; Gidding, SS.; Kurosaki, TT.; Bild DE Prevalence of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in a General Population of Young Adults. Echocardiographic Analysis of 4111 Subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation 1995, 92, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabib, A.; Loire, R.; Chalabreysse, L.; Meyronnet, D.; Miras, A.; Malicier, D.; Thivolet, F.; Chevalier, P.; Bouvagnet, P. Circumstances of Death and Gross and Microscopic Observations in a Series of 200 Cases of Sudden Death Associated with Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy and/or Dysplasia. Circulation 2003, 108, 3000–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.J.; Stramba-Badiale, M.; Crotti, L.; Pedrazzini, M.; Besana, A.; Bosi, G.; Gabbarini, F.; Goulene, K.; Insolia, R.; Mannarino, S.; et al. Prevalence of the Congenital Long-QT Syndrome. Circulation 2009, 120, 1761–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akioyamen, L.E.; Genest, J.; Shan, S.D.; Reel, R.L.; Albaum, J.M.; Chu, A.; Tu, J.V. Estimating the Prevalence of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, H. FBN1-Related Marfan Syndrome - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelf Available online:. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1335/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Milewicz, D. Heritable Thoracic Aortic Disease Overview - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelf Available online:. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1120/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Loeys-Dietz Syndrome - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelf Available online:. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1133/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Byers, P. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome - GeneReviews® - NCBI Bookshelf Available online:. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1494/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Ponder, B.; Pharoah, P.D.P.; Ponder, B.A.J.; Lipscombe, J.M.; Basham, V.; Gregory, J.; Gayther, S.; Dunning, A. Prevalence and Penetrance of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in a Population-Based Series of Breast Cancer Cases. Br J Cancer 2000, 83, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teugels, E.; De Brakeleer, S.; Goelen, G.; Lissens, W.; Sermijn, E.; De Grève, J. De Novo Alu Element Insertions Targeted to a Sequence Common to the BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genes. Hum Mutat 2005, 26, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, A.K.; Jenkins, M.A.; Dowty, J.G.; Antoniou, A.C.; Lee, A.; Giles, G.G.; Buchanan, D.D.; Clendenning, M.; Rosty, C.; Ahnen, D.J.; et al. Prevalence and Penetrance of Major Genes and Polygenes for Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. A Peculiar Form of Peripheral Neuropathy; Familiar Atypical Generalized Amyloidosis with Special Involvement of the Peripheral Nerves. Brain 1952, 75, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.; Coelho, T.; Barros, J.; Sequeiros, J. Genetic Epidemiology of Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy (FAP)-Type I in Póvoa Do Varzim and Vila Do Conde (North of Portugal). Am. J. Med. Genet. (Neuropsychiatr. Genet. ) 1995, 60, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, M.; Coelho, T.; Conceição, I.; Duarte-Ramos, F.; de Carvalho, M.; Costa, J. Epidemiology of Transthyretin Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy in Portugal: A Nationwide Study. Neuroendocrinology 2018, 51, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, T.; Maurer, M.S.; Suhr, O.B. THAOS - The Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey: Initial Report on Clinical Manifestations in Patients with Hereditary and Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Curr Med Res Opin 2013, 29, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungunsukh, O.; Deuster, P.; Muldoon, S.; O’Connor, F.; Sambuughin, N. Estimating Prevalence of Malignant Hyperthermia Susceptibility through Population Genomics Data. Br J Anaesth 2019, 123, e461–e463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fridriksdottir, R.; Jonsson, A.J.; Jensson, B.O.; Sverrisson, K.O.; Arnadottir, G.A.; Skarphedinsdottir, S.J.; Katrinardottir, H.; Snaebjornsdottir, S.; Jonsson, H.; Eiriksson, O.; et al. Sequence Variants in Malignant Hyperthermia Genes in Iceland: Classification and Actionable Findings in a Population Database. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 29, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, M.; Pagliardini, S.; Yasuda, M.; Tukel, T.; Thiagarajan, G.; Sakuraba, H.; Ponzone, A.; Desnick, R.J. High Incidence of Later-Onset Fabry Disease Revealed by Newborn Screening. Am J Hum Genet 2006, 79, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Kido, J.; Yoshida, S.; Sugawara, K.; Momosaki, K.; Inoue, T.; Tajima, G.; Sawada, H.; Mastumoto, S.; Endo, F.; et al. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in the Western Region of Japan. Mol Genet Metab Rep 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, B.K.; Charrow, J.; Hoganson, G.E.; Waggoner, D.; Tinkle, B.; Braddock, S.R.; Schneider, M.; Grange, D.K.; Nash, C.; Shryock, H.; et al. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders in Illinois: The Initial 15-Month Experience. J. Pediatr. 2017, 190, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwu, W.L.; Chien, Y.H.; Lee, N.C.; Chiang, S.C.; Dobrovolny, R.; Huang, A.C.; Yeh, H.Y.; Chao, M.C.; Lin, S.J.; Kitagawa, T.; et al. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in Taiwan Reveals a High Incidence of the Later-Onset GLA Mutation c.936+919G>A (IVS4+919G>A). Hum Mutat 2009, 30, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, M.; Casanova, F.; Tyrrell, J.S.; Cannon, S.; Wood, A.R.; Fife, N.; Young, K.; Oram, R.A.; Weedon, M.N. Prevalence of Fabry Disease-Causing Variants in the UK Biobank. J Med Genet 2023, 60, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, O.; Gal, A.; Faria, R.; Gaspar, P.; Miltenberger-Miltenyi, G.; Gago, M.F.; Dias, F.; Martins, A.; Rodrigues, J.; Reimão, P.; et al. Founder Effect of Fabry Disease Due to p.F113L Mutation: Clinical Profile of a Late-Onset Phenotype. Mol Genet Metab 2020, 129, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Ricci, R.; Widmer, U.; Dehout, F.; Garcia De Lorenzo, A.; Kampmann, C.; Linhart, A.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Ries, M.; Beck, M. Fabry Disease Defined: Baseline Clinical Manifestations of 366 Patients in the Fabry Outcome Survey. Eur J Clin Invest 2004, 34, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E.H.; Imperatore, G.; Burke, W. HFE Gene and Hereditary Hemochromatosis: A HuGE Review. Human Genome Epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2001, 154, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phatak, P.D.; Sham, R.L.; Raubertas, R.F.; Dunnigan, K.; O’leary, T.; Braggins, C.; Cappuccio, J.D. Prevalence of Hereditary Hemochromatosis in 16031 Primary Care Patients. 1998, 129, 954–961. [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.C.; Reboussin, D.M.; Barton, J.C.; Mclaren, C.E.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Mclaren, G.D.; Dawkins, F.W.; Acton, R.T.; Harris, E.L.; Gordeuk, V.R.; et al. Hemochromatosis and Iron-Overload Screening in a Racially Diverse Population. New Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, R.; McCabe, P.; Fell, G.; Russell, R. Wilson’s Disease in Scotland. Gut 1991, 32, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, A.J.; Durkie, M.; Hague, S.; McLay, K.; Emmerson, J.; Lo, C.; Klaffke, S.; Joyce, C.J.; Dhawan, A.; Hadzic, N.; et al. A Genetic Study of Wilson’s Disease in the United Kingdom. Brain 2013, 136, 1476–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, R.; Caseiro, C.; Lemos, M.; Lopes, L.; Fontes, A.; Ribeiro, H.; Pinto, E.; Silva, E.; Rocha, S.; Marcão, A.; et al. Prevalence of Lysosomal Storage Diseases in Portugal. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 12, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, B. Worldwide Survey of Neonatal Screening for Biotinidase Deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis 1991, 14, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, S.; Biggio, J.R.; Saller, D.N.; Giardine, R. Committee Opinion Number 432; 2017; Vol. 129;

- Board of Directors, A. The Use of ACMG Secondary Findings Recommendations for General Population Screening: A Policy Statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1467–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, S.; Ribeiro, M.; Schnur, J.; Alves, F.; Moniz, N.; Seelow, D.; Freixo, J.P.; Silva, P.F.; Oliveira, J. Analysis of Regions of Homozygosity: Revisited Through New Bioinformatic Approaches. BioMedInformatics 2024, 4, 2374–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- População Residente Por Município Segundo Os Censos | Pordata. Available online: Https://Www.Pordata.Pt/Municipios/Populacao+residente+segundo+os+censos+total+e+por+sexo-17 (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best Practice Guidelines - The Association for Clinical Genomic Science Available online:. Available online: https://www.acgs.uk.com/quality/best-practice-guidelines/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Criteria Specification Registry Available online:. Available online: https://cspec.genome.network/cspec/ui/svi/ (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- CanVIG-UK Consensus Specifications | CanGene-CanVar Available online:. Available online: https://www.cangene-canvaruk.org/canvig-uk-guidance (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Hayesmoore, J.B.; Bhuiyan, Z.A.; Coviello, D.A.; du Sart, D.; Edwards, M.; Iascone, M.; Morris-Rosendahl, D.J.; Sheils, K.; van Slegtenhorst, M.; Thomson, K.L. EMQN: Recommendations for Genetic Testing in Inherited Cardiomyopathies and Arrhythmias. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).