Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

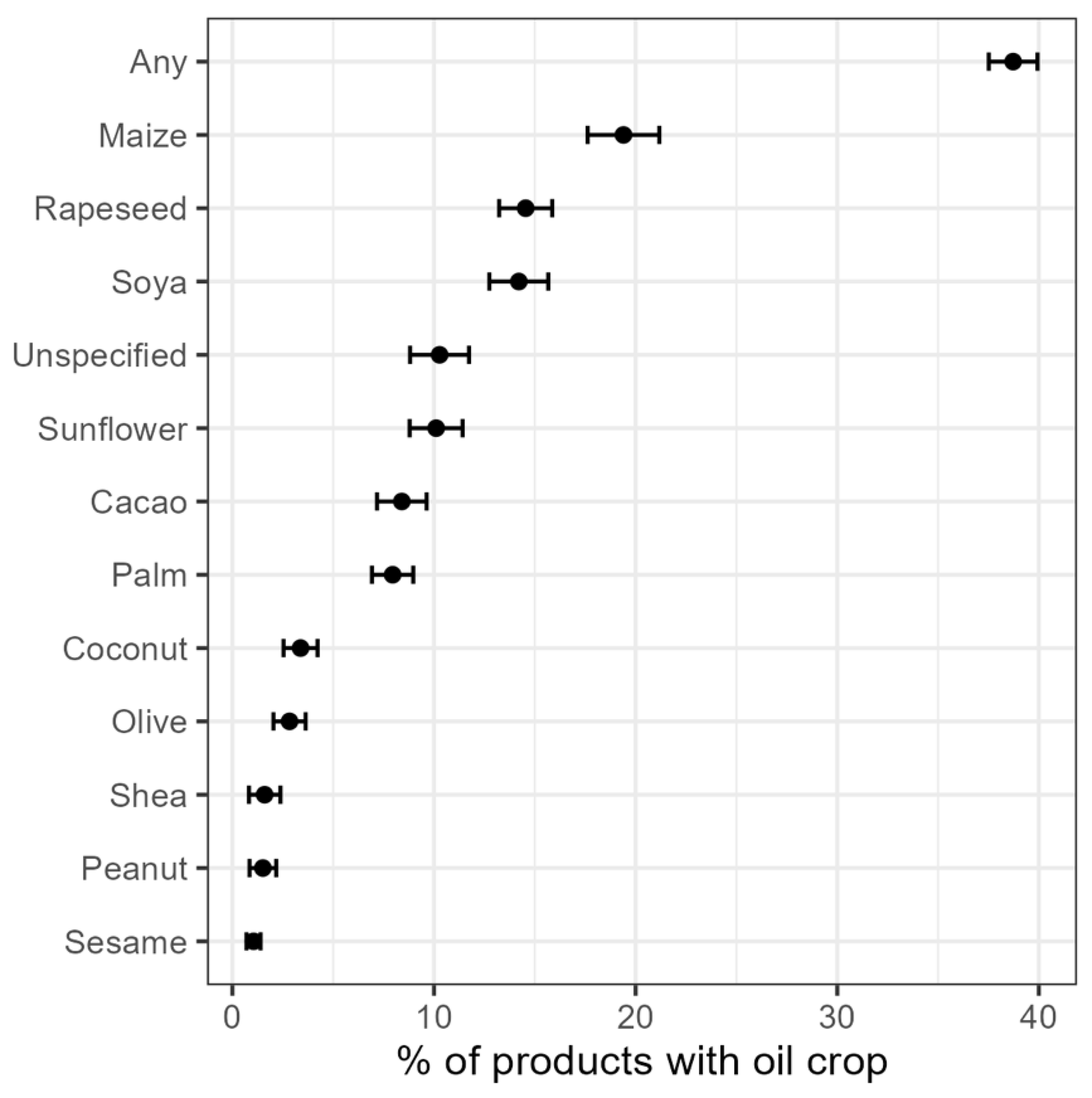

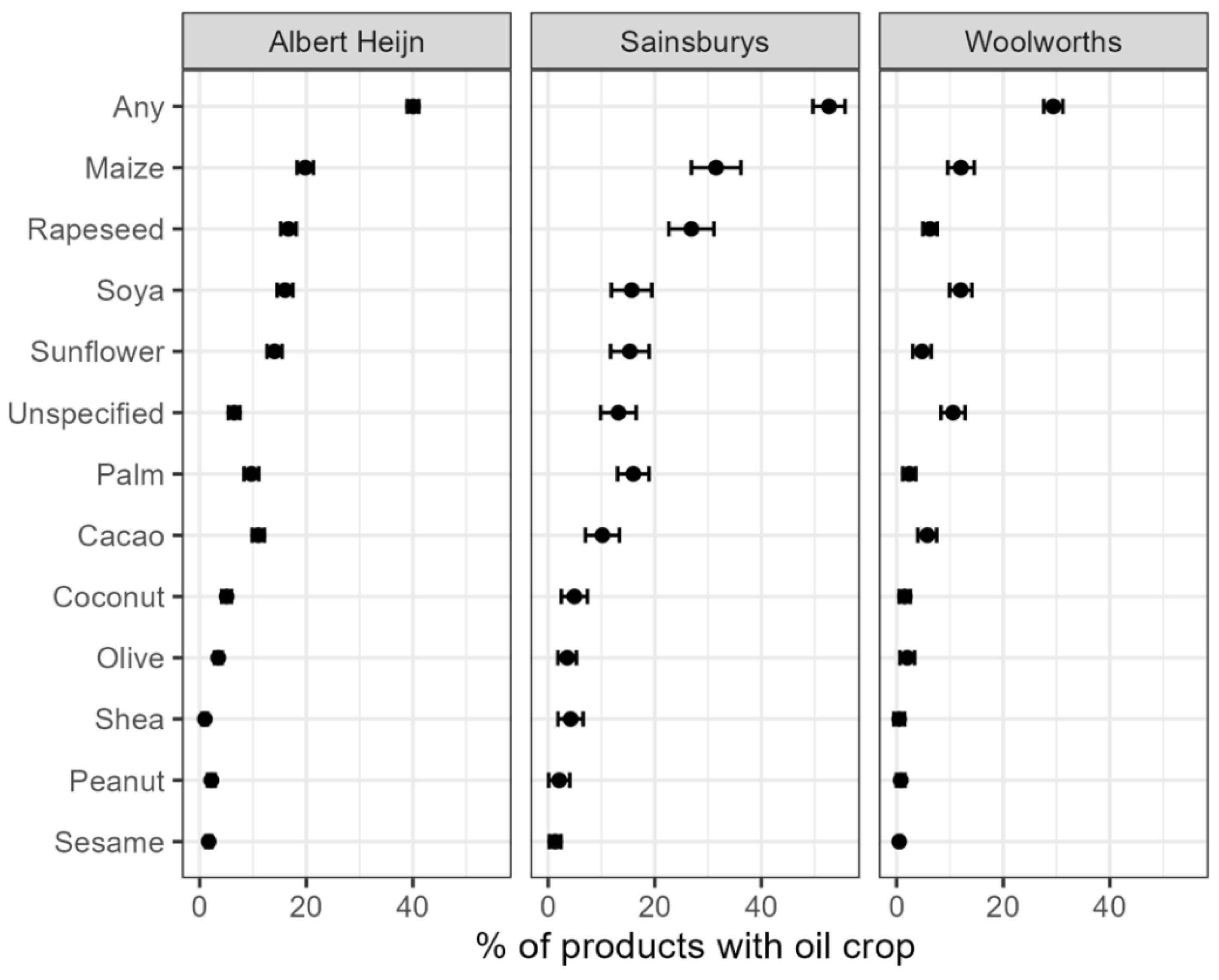

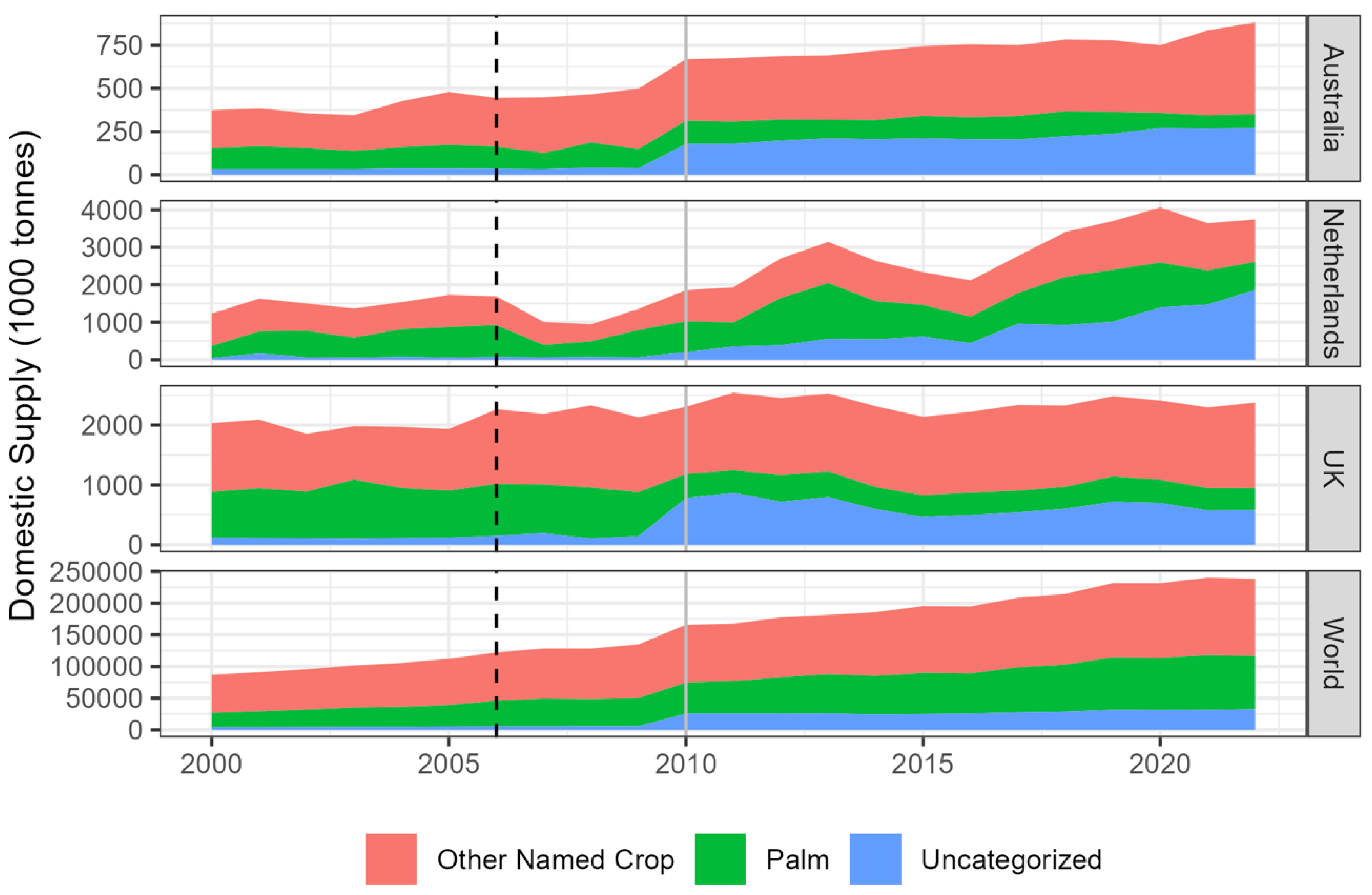

The claim that 50% of supermarket products contain palm oil is widely cited and repeated to underscore the relevance of activist campaigns and sustainability efforts in the oil palm sector. Yet evidence supporting this claim has never been publicly available. We investigated the accuracy of this claim at three large supermarket chains across three countries, where adequate online product and ingredient data were available. We compiled and analysed ingredient lists from approximately 1,600 food products from three supermarkets in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Australia to evaluate the prevalence of palm and palm kernel oil, as well as other major vegetable oil crops. Across these supermarkets, palm and/or palm kernel oil were explicitly listed in 7.9% (95% CI [6.9%, 9.0%]) of products, whereas maize (19% [18%, 21%]), rapeseed (15% [13%, 16%]), and soya (14% [13%, 16%]) were more prevalent. Up to 40% (95% CI [37%, 43%]) of products at these supermarkets may contain palm oil through unspecified vegetable oils or oleochemicals, which were found in about 18% of all sampled products. This underscores a broader challenge: modern processed foods are part of complex global supply chains that rely on interchangeable commodities such as palm oil. While traceability mechanisms like those promoted by the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) aim to enhance upstream accountability, consumer-facing labelling transparency remains inadequate. We emphasise the need for clearer food labelling and broader systems-level impact assessments if consumers are to make fully informed choices to align with their values and goals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Claim Tracing

2.2. Supermarket Selection

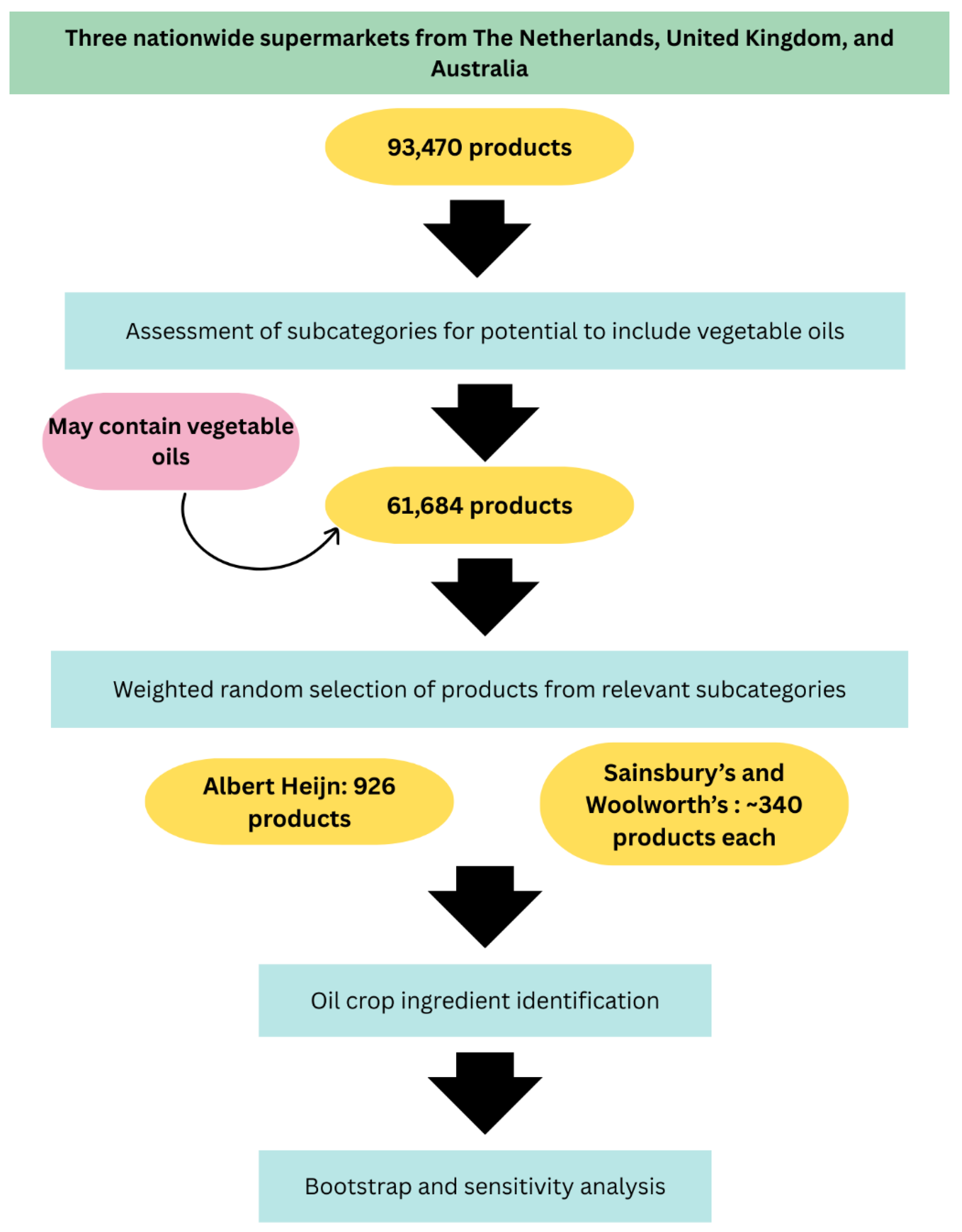

2.3. Product Sampling Strategy

2.4. Ingredient Data

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interests

References

- Van Rijswijk, W.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer needs and requirements for food and ingredient traceability information. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 36, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, G.; Padfield, R.; Kraamwinkel, D. Contested representations: A comparative analysis of palm oil sustainability in Malaysian and Dutch media. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candellone E, Aleta A, Ferraz de Arruda H, Meijaard E, Moreno Y 2024 Understanding the vegetable oil debate and its implications for sustainability through social media. Comms. Earth Env. 5 391. [CrossRef]

- Gassler, B.; Spiller, A. Is it all in the MIX? Consumer preferences for segregated and mass balance certified sustainable palm oil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPorte, P.S.; Meijaard, E.; Carlson, K.M. The impact of reading a synthesis report on perceptions of palm oil in the global conservation community. PLOS Sustain. Transform. 2025, 4, e0000183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Brooks, T.M.; Carlson, K.M.; Slade, E.M.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Lee, J.S.H.; Santika, T.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Struebig, M.J.; et al. The environmental impacts of palm oil in context. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard E, Virah-Sawmy M, Newing H S, Ingram V, Holle M J M, Pasmans T, et al 2024 Exploring the future of vegetable oils. Oil crop implications - fats, forests, forecasts, and futures. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN and SNSB. 186 p.

- Ostfeld, R.; Howarth, D.; Reiner, D.; Krasny, P. Peeling back the label—exploring sustainable palm oil ecolabelling and consumption in the United Kingdom. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Singh, G.A. From Stimulus to Response: Understanding the Causes and Outcomes of Consumer Activism. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 24, 820–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Wwf palm oil buyers’ scorecard 2009. How ‘green’ is the palm oil purchased by european companies? Gland, Switzerland: WWF International/Forest Conversion Programme; 2009.

- RSPO. Factsheet on home and personal care sector. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil; 2021.

- Gupta A, Mason M. A transparency turn in global environmental governance. In: Gupta A, Mason M, editors. Transparency in global environmental governance: Critical perspectives. Earth system governance. Cambridge MA, USA: MIT Press; 2014. p. 3-38.

- Meijaard, E.; Sheil, D. The Moral Minefield of Ethical Oil Palm and Sustainable Development. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2019, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainforest Foundation Norway 2012 The day the norwegians rejected palm oil and deforestation. Https://www.Regnskog.No/en/long-reads-about-life-in-the-rainforest/the-day-the-norwegians-rejected-palm-oil-and-deforestation-1. Accessed on 30 july 2025.

- Crothers L 2019 Norway sees sharp drop in palm oil biofuel consumption after ban on government purchasing. Https://news.Mongabay.Com/2019/06/norway-sees-sharp-drop-in-palm-oil-biofuel-consumption-after-ban-on-government-purchasing/?Utm_source=chatgpt.Com, accessed on 5 august 2025.

- Ferrero 2024 Palm oil charter.

- Mackay H 2019 Iceland removed own label from 17 products rather than palm oil. Https://www.Bbc.Com/news/uk-46984349. Accessed on 20 may 2025.

- Sheargold E, Mitchell A D 2011 Oils ain’t oils: Product labelling, palm oil and the wto. Melbourne J. Int. Law. 12 [148]-70.

- Pacheco, P.; Schoneveld, G.; Dermawan, A.; Komarudin, H.; Djama, M. Governing sustainable palm oil supply: Disconnects, complementarities, and antagonisms between state regulations and private standards. Regul. Gov. 2018, 14, 568–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard E, Sheil D, Virah-Sawmy M 2025 No oil crop is inherently bad — but our thinking might be. Cell Rep. Sust. [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Gardner, T.A.; Meyfroidt, P.; Persson, U.M.; Adams, J.; Azevedo, T.; Lima, M.G.B.; Baumann, M.; Curtis, P.G.; De Sy, V.; et al. Disentangling the numbers behind agriculture-driven tropical deforestation. Science 2022, 377, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, M.W.; French, R.; Jones, B.; Fischer, A.; Holland, A.; Roybal, I.; White, T.; Steibl, S.; Anderegg, L.D.L.; Young, H.; et al. Satellite imagery reveals widespread coconut plantations on Pacific atolls. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 124095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, E.D.; Weisse, M.; Harris, N.; Schneider, M. Estimating the Role of Seven Commodities in Agriculture-Linked Deforestation: Oil Palm, Soy, Cattle, Wood Fiber, Cocoa, Coffee, and Rubber. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.-P.; Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.; Adusei, B.; Pickering, J.; Adami, M.; Lima, A.; Zalles, V.; Stehman, S.V.; Di Bella, C.M.; et al. Massive soybean expansion in South America since 2000 and implications for conservation. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathilake, H.M.; Prescott, G.W.; Carrasco, L.R.; Rao, M.; Symes, W.S. Drivers of deforestation and degradation for 28 tropical conservation landscapes. AMBIO 2020, 50, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Abrams, J.F.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Voigt, M.; Sheil, D. Coconut oil, conservation and the conscientious consumer. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R757–R758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AllergyUK 2022 Your quick guide to: Your quick guide to: Soya (soy) allergy. Version 3. Https://www.Allergyuk.Org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/soya-allergy.Pdf. Accessed on 17 september 2025.

- Woolworths. Policy - sustainable palm oil sourcing for woodworths own brand food and formulated non-food products. Pol.022. Woolworths Group Limited; 2023.

- Albert Heijn 2024 Duurzame keurmerken. Https://www.Ah.Nl/inspiratie/duurzaamheid/duurzame-keurmerken. Accessed on 19 february 2025.

- Sainsbury 2024 Sustainable palm oil. Https://www.About.Sainsburys.Co.Uk/sustainability/plan-for-better/our-stories/2023/palm-oil. Dated 24 june 2024. Accessed 18 february 2025.

- Maganja, D.; Davies, T.; Sanavio, L.; Louie, J.C.Y.; Huffman, M.D.; Trieu, K.; Wu, J.H.Y. Current food labelling practices in online supermarkets in Australia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olzenak, K.; French, S.; Sherwood, N.; Redden, J.P.; Harnack, L. How Online Grocery Stores Support Consumer Nutrition Information Needs. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K. Fats and oils as oleochemical raw materials. Pure Appl. Chem. 2000, 72, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.; Raikova, S.; Chuck, C.J. The viability and desirability of replacing palm oil. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Http://www.R-project.Org/. Vienna, Austria; 2024.

- Lumley T 2024 Survey: Analysis of complex survey samples. R package version 4.4.

- Schneider B 2023 Svrep: Tools for creating, updating, and analyzing survey replicate weights. R package version 0.6.0.

- SASPO. Guide to sustainable palm oil for singapore companies: Economic opportunities and sourcing guidelines. Singapore: SASPO,; 2018.

- FAO 2020 Faostat. Food balances (-2013, old methodology and population). Metadata. Https://www.Fao.Org/faostat/en/#data/fbsh/metadata.

- FAO 2024 Food balances (2010-). Metadata. Https://www.Fao.Org/faostat/en/#data/fbs/metadata.

- Rainforest Foundation Norway 2014 Running a successful palm oil campaign. Https://www.Regnskog.No/en/what-we-do/how-we-create-political-change/running-a-successful-palm-oil-campaign?Utm_source=chatgpt.Com. Accessed on 31 july 2025.

- Trygg Mat 2025 Palmeolje: Disse matvarene inneholder palmeolje. Https://www.Tryggmat.App/tilsetninger/palmeolje. Accessed on 5 august 2025.

- Butler S 2022 Iceland reverts to palm oil ‘with regret’ as ukraine war hits food prices. Https://www.Theguardian.Com/business/2022/mar/28/iceland-reverts-to-palm-oil-with-regret-as-ukraine-war-hits-food-prices. Accessed on 5 february 2025.

- Retail Detail 2025 Expansion earns albert heijn market share growth despite tobacco ban. Dated 21 january 2025. Accessed 26 february 2025. Https://www.Retaildetail.Eu/news/food/expansion-earns-albert-heijn-market-share-growth-despite-tobacco-ban/.

- Statista 2024 Market share of grocery stores in great britain from january 2017 to november 2024. Dated 4 december 2024. Accessed 26 february 2025. Https://www.Statista.Com/statistics/280208/grocery-market-share-in-the-united-kingdom-uk/.

- Statista 2024 Market share of grocery retailers in australia in financial year 2023. Dated 31 may 2024. Accessed 26 february 2025. Https://www.Statista.Com/statistics/994601/grocery-retailer-market-share-australia/.

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet,.

- Shah, U.A.; Merlo, G. Personal and Planetary Health—The Connection With Dietary Choices. JAMA 2023, 329, 1823–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Talsma, E.F.; Chang, Z.; Wen, X.; Fan, S.; Veer, P.V.; Biesbroek, S. Health outcomes, environmental impacts, and diet costs of adherence to the EAT-Lancet Diet in China in 1997–2015: a health and nutrition survey. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2024, 8, e1030–e1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriacò, M.V.; Galli, N.; Latella, M.; Rulli, M.C. Pressure on Global Forests: Implications of Rising Vegetable Oils Consumption Under the EAT-Lancet Diet. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2025, 31, e70077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Open Food Facts 2025 Https://world.Openfoodfacts.Org/. Accessed on 17 september 2025.

- Grunert, K.G.; Wills, J.M. A review of European research on consumer response to nutrition information on food labels. J. Public Health 2007, 15, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, n.d. Regulation on deforestation-free products. Https://environment.Ec.Europa.Eu/topics/forests/deforestation/regulation-deforestation-free-products_en. Accessed on 17 september 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).