Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

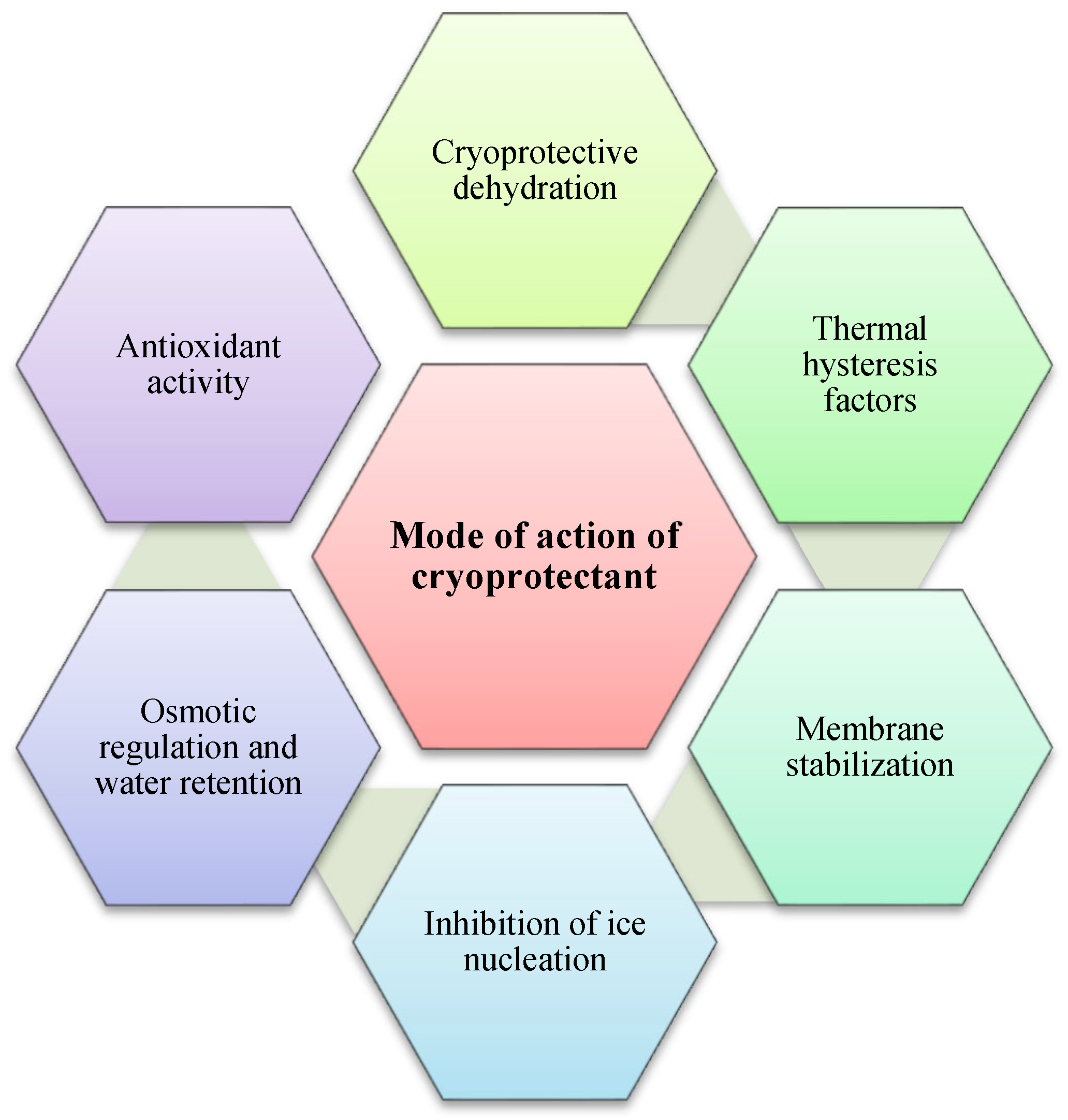

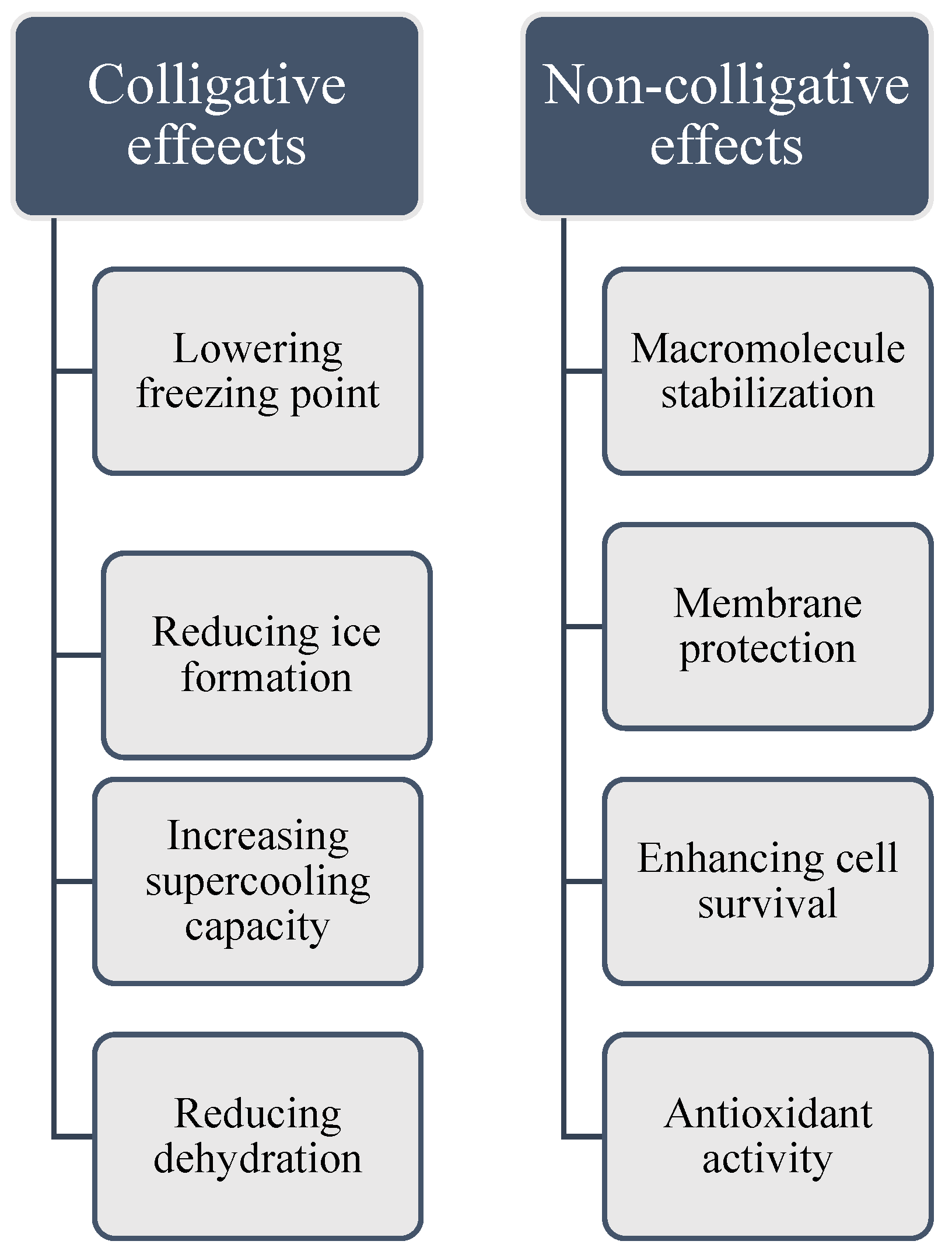

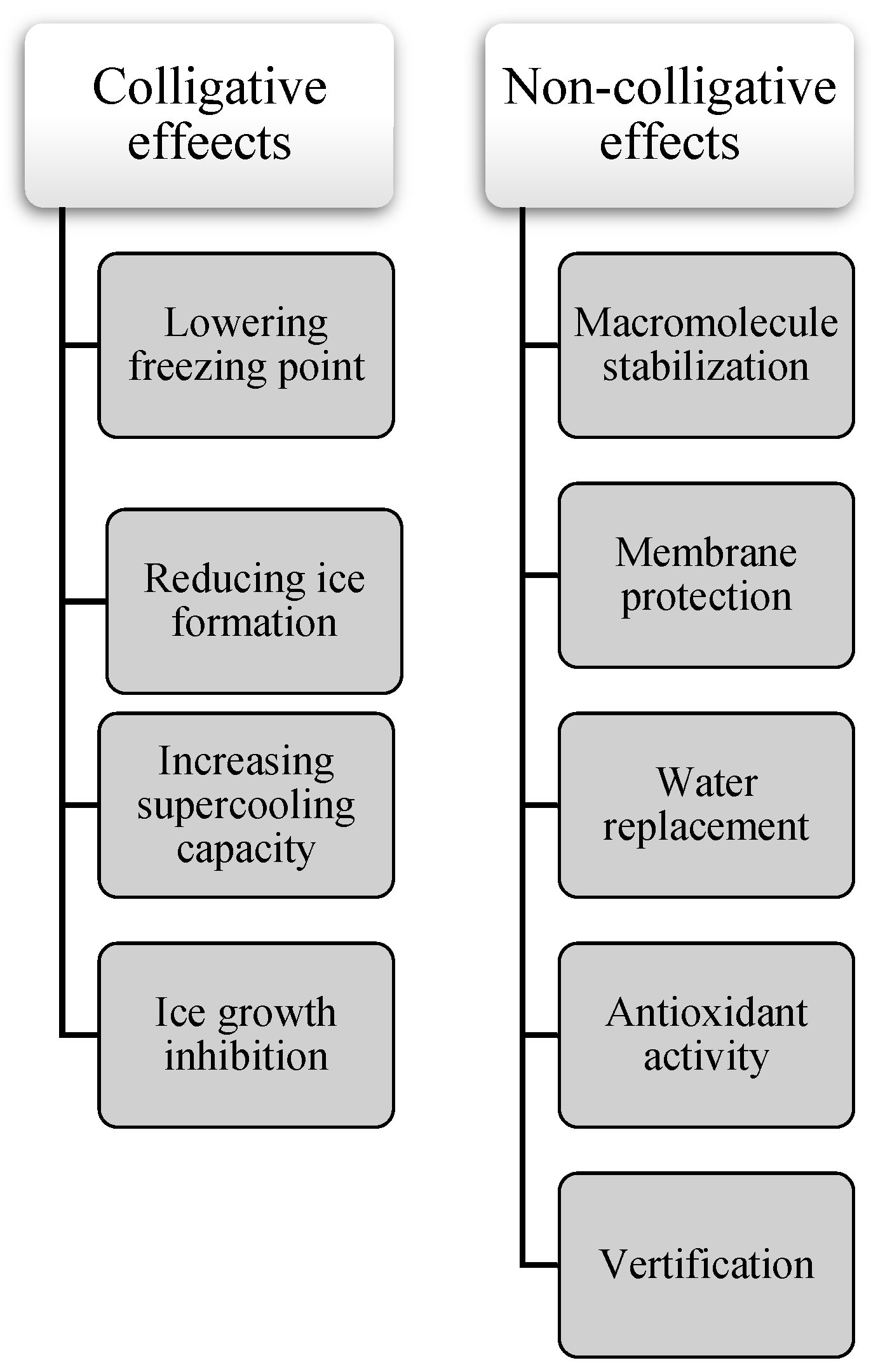

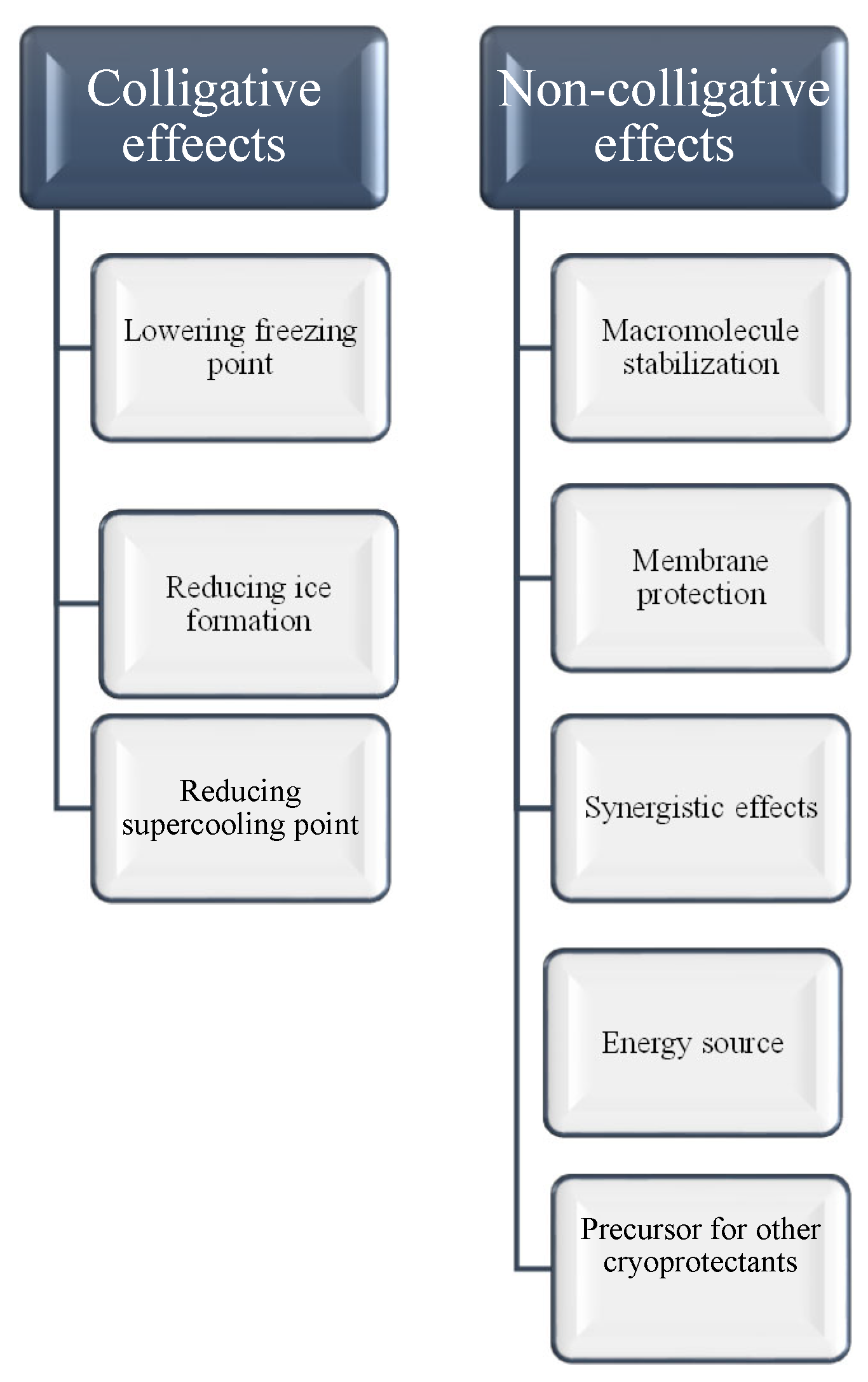

2. Mode of Action of Cryoprotectants

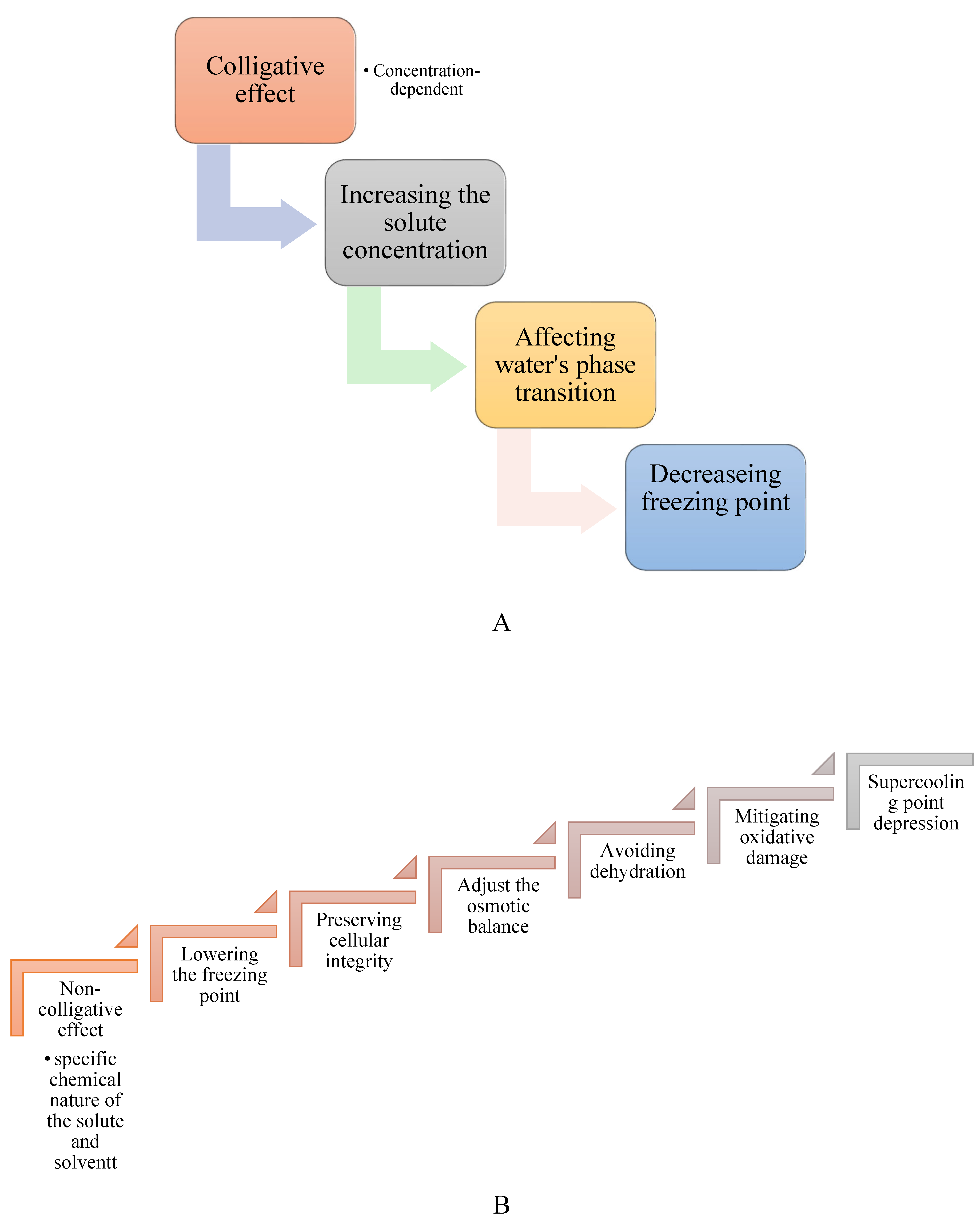

Colligative Effects (Concentration-Dependent) and Non-Colligative Cryoprotective Function

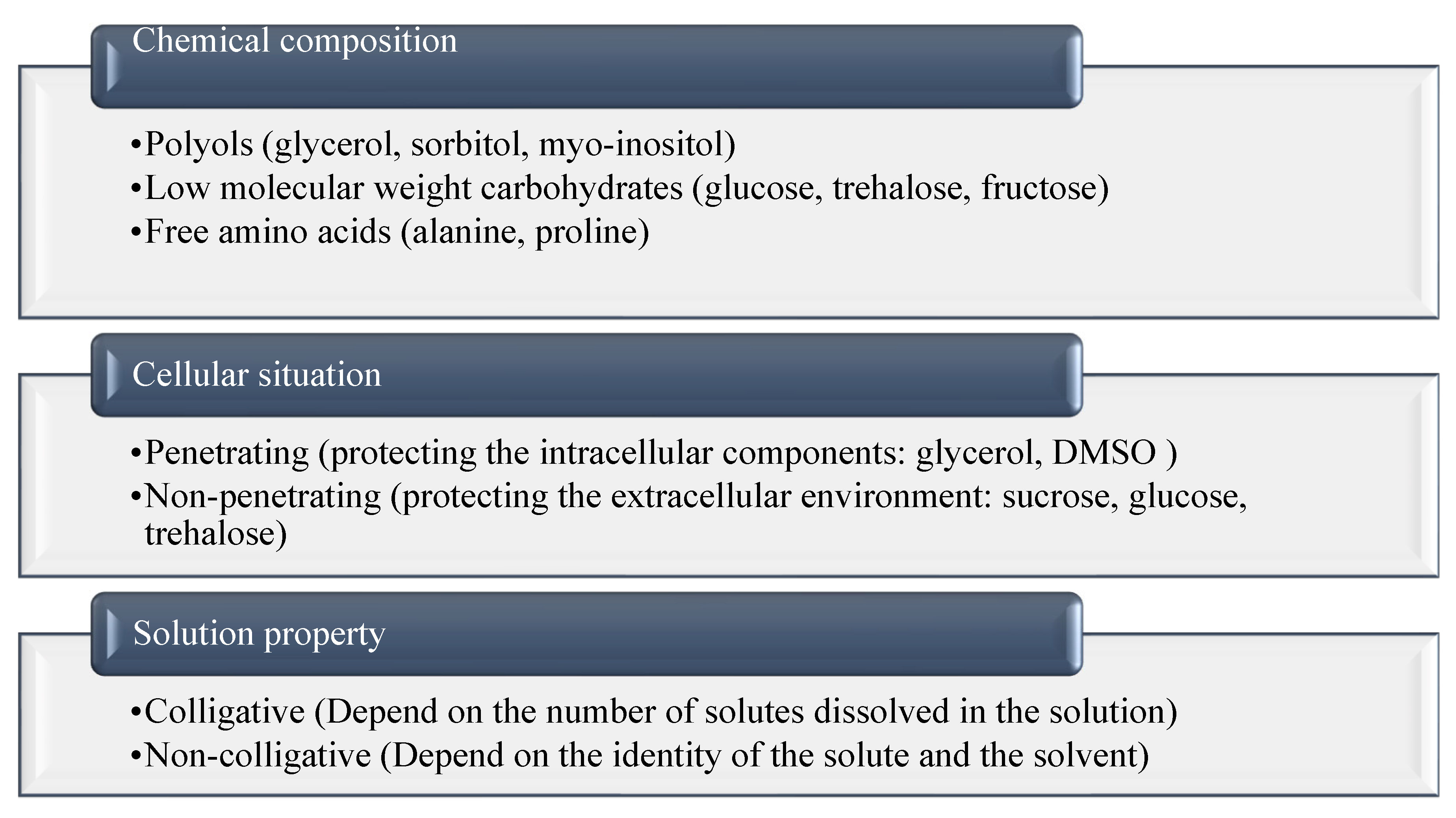

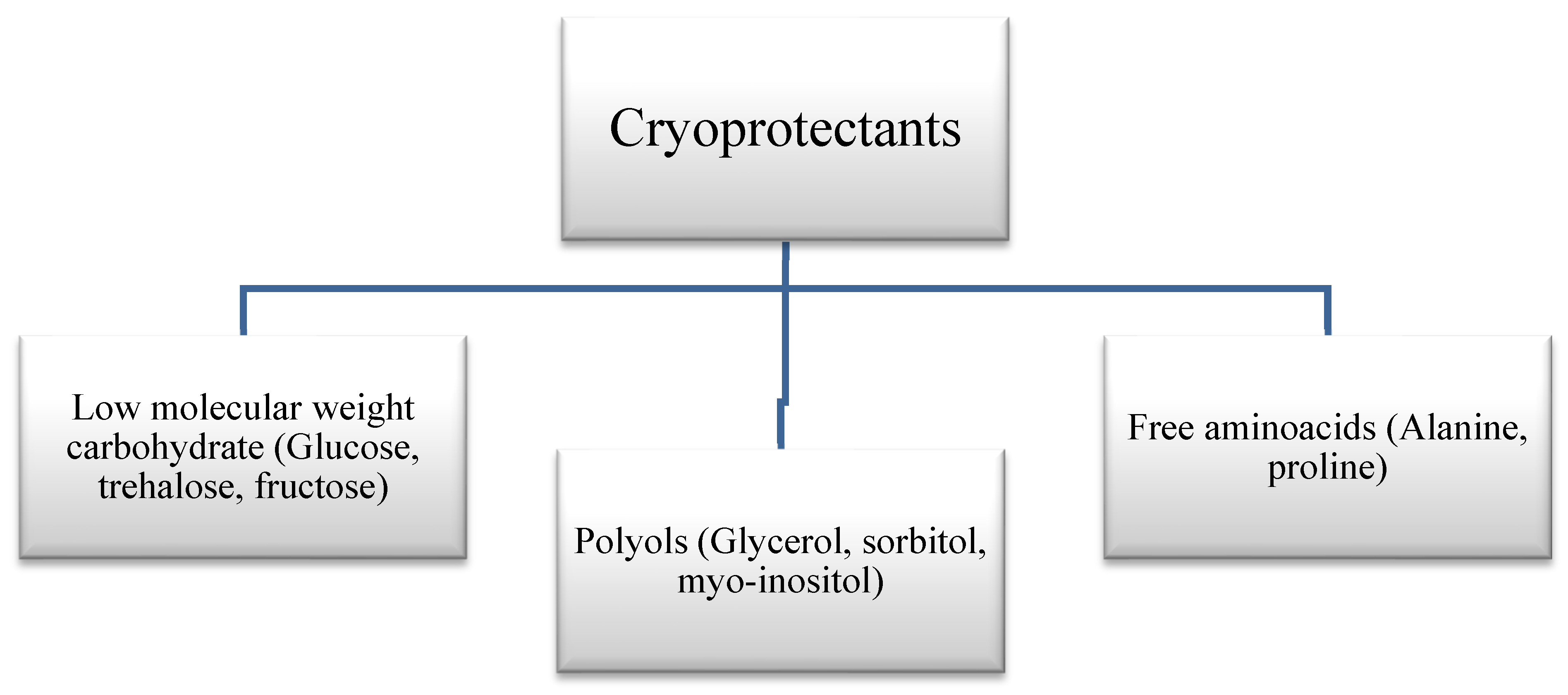

3. Cryoprotectant Classification

3.1. Chemical Composition

3.2. Permeability and Cellular Situation

3.3. Solution Property

4. Predominant Cryoprotectants of Insects

4.1. Polyols

4.1.1. Mode of Action of Glycerol as a Cryoprotectant

4.1.2. Mode of Action of Trehalose as a Cryoprotectant

4.1.3. Mode of Action of Glucose as a Cryoprotectant

4.1.4. Mode of Action of Myo-Inositol as a Cryoprotectant

4.1.5. Mode of Action of Sorbitol as a Cryoprotectant

4.1.6. Mode of Action of Fructose as a Cryoprotectant

4.2. Amino Acids as Cryoprotectants

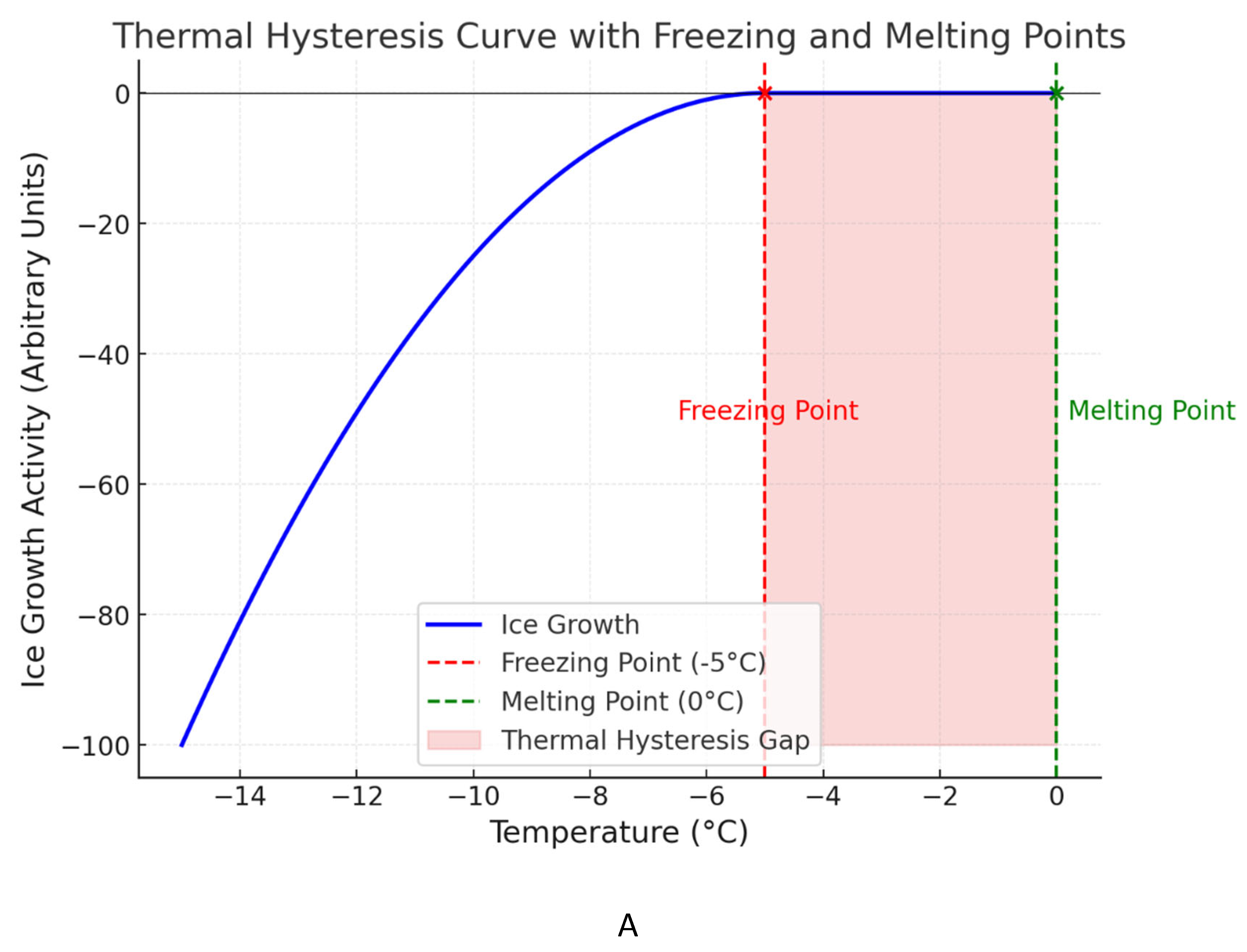

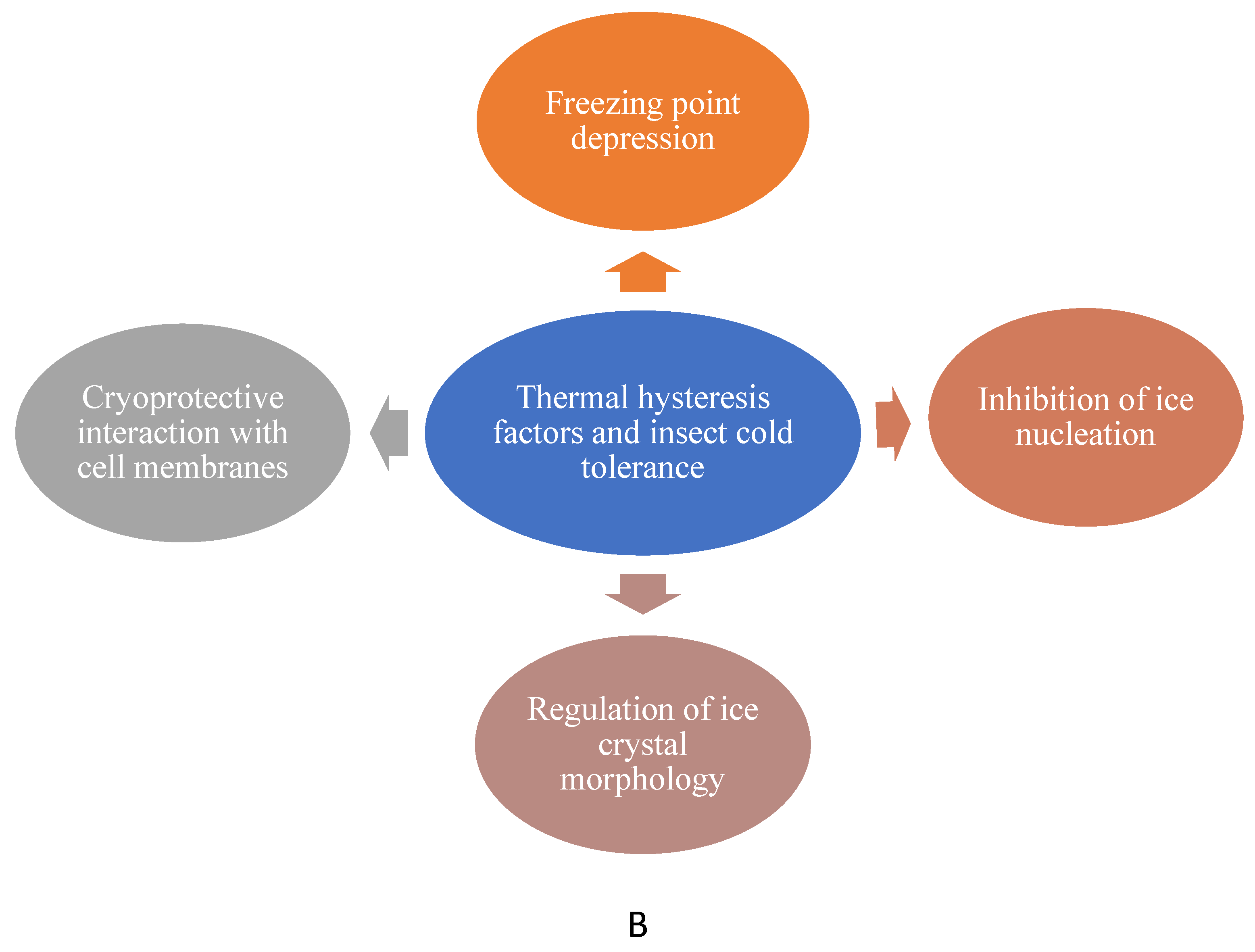

4.3. Thermal Hysteresis Factors

4.4. Ice Nucleating Proteins (INPs)

5. Insect Strategies for Accumulating Cryoprotectants

5.1. Accumulation of a Single Cryoprotectant in Large Quantities

5.2. Accumulation of Two Primary Cryoprotectants at High Levels

5.3. Combination of Different Cryoprotectants

6. Accumulation of Cryoprotectants Over Time

6.1. Rapid Accumulation Before Cold Exposure

6.2. Incremental Accumulation During Cold Exposure

6.3. Basal Accumulation Throughout Life

7. Cryoprotectant Accumulation Processes

8. Cryoprotectant Accumulation in Other Ectotherms

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Logan, J.D.; Wolesensky, W.; Joern, A. Temperature-Dependent Phenology and Predation in Arthropod Systems. Ecol Modell 2006, 196, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Rudolf, V.H.W. Phenology, Ontogeny and the Effects of Climate Change on the Timing of Species Interactions. Ecol Lett 2010, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Régnière, J.; St-Amant, R.; Duval, P. Predicting Insect Distributions under Climate Change from Physiological Responses: Spruce Budworm as an Example. Biol Invasions 2012, 14, 1571–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, B.J.; Coello Alvarado, L.E.; Ferguson, L. V. An Invitation to Measure Insect Cold Tolerance: Methods, Approaches, and Workflow. J Therm Biol 2015, 53, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Zong, S. Cold Hardiness of Overwintering Larvae of Sphenoptera Sp. (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in Western China. J Econ Entomol 2018, 111, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, B.J.; Vernon, P.; Klok, C.J.; Chown, S.L. Insects at Low Temperatures: An Ecological Perspective. Trends Ecol Evol 2003, 18, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Kikawada, T.; Minagawa, N.; Yukuhiro, F.; Okuda, T. Mechanism Allowing an Insect to Survive Complete Dehydration and Extreme Temperatures. J Exp Biol 2002, 205, 2799–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, J.S.; Gerday, C.; Parker, A.; Marahiel, M.A.; Shanks, I.A.; Davies, P.L.; Warren, G. Insects and Low Temperatures: From Molecular Biology to Distributions and Abundance. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2002, 357, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemani, M.; Izadi, H.; Mahdian, K.; Khani, A.; Amin samih, M. Study on the Physiology of Diapause, Cold Hardiness and Supercooling Point of Overwintering Pupae of the Pistachio Fruit Hull Borer, Arimania Comaroffi. J Insect Physiol 2012, 58, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemani, M.; Izadi, H.; Mahdian, K.; Khani, A.; Amin samih, M. Study on the Physiology of Diapause, Cold Hardiness and Supercooling Point of Overwintering Pupae of the Pistachio Fruit Hull Borer, Arimania Comaroffi. J Insect Physiol 2012, 58, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudmagham, A.; Izadi, H.; Mohammadzadeh, M. Expanded Supercooling Capacity With No Cryoprotectant Accumulation Underlies Cold Tolerance of the European Grapevine Moth. J Econ Entomol 2021, 114, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.E.; Lee Richard E, Jr.; Lee, R.E.; Lee Jr., R. E. Insect Cold-Hardiness: To Freeze or Not to Freeze. Bioscience 1989, 39, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milonas, P.G.; Savopoulou-Soultani, M. Cold Hardiness in Diapause and Non-Diapause Larvae of the Summer Fruit Tortrix, Adoxophyes Orana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Eur J Entomol 1999, 96, 183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh, M.; Izadi, H. Cooling Rate and Starvation Affect Supercooling Point and Cold Tolerance of the Khapra Beetle, Trogoderma Granarium Everts Fourth Instar Larvae (Coleoptera: Dermestidae). J Therm Biol 2018, 71, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockton, D.; Wallingford, A.; Rendon, D.; Fanning, P.; Green, C.K.; Diepenbrock, L.; Ballman, E.; Walton, V.M.; Isaacs, R.; Leach, H.; et al. Interactions between Biotic and Abiotic Factors Affect Survival in Overwintering Drosophila Suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Environ Entomol 2019, 48, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariassen, K.E. Physiology of Cold Tolerance in Insects. Physiol. Rev. 1985, 65, 799–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K.E.; Sinclair, B.J. The Impacts of Repeated Cold Exposure on Insects. Journal of Experimental Biology 2012, 215, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colinet, H.; Sinclair, B.J.; Vernon, P.; Renault, D. Insects in Fluctuating Thermal Environments. Annu Rev Entomol 2015, 60, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Zhao, R.-N.; Li, Y.; Li, H.-P.; Xie, M.-H.; Liu, J.-F.; Yang, M.-F.; Wu, C.-X. Cold Tolerance Strategy and Cryoprotectants of Megabruchidius Dorsalis in Different Temperature and Time Stresses. Front Physiol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxopeus, J.; Sinclair, B.J. Mechanisms Underlying Insect Freeze Tolerance. Biological Reviews 2018, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankit, J. Joshi A Review and Application of Cryoprotectant: The Science of Cryonics. PharmaTutor 2016, 4, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marcantonini, G.; Zatini, L.; Costa, S.; Passerini, M.; Rende, M.; Luca, G.; Basta, G.; Murdolo, G.; Calafiore, R.; Galli, F. Natural Cryoprotective and Cytoprotective Agents in Cryopreservation: A Focus on Melatonin. Molecules 2022, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.-Q.; Tan, P.-C.; Gao, Y.-M.; Zhang, X.-J.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, D.-N.; Zhou, S.-B.; Li, Q.-F. The Effect of Glycerol as a Cryoprotective Agent in the Cryopreservation of Adipose Tissue. Stem Cell Res Ther 2022, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B.J. Cryoprotectants: The Essential Antifreezes to Protect Life in the Frozen State. Cryo-Letters 2004, 25, 375–388. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, K.B.; Storey, J.M. Biochemistry of Cryoprotectants. Insects at Low Temperature 1991, 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincha, D.K.; Schmidt, J.E.; Heber, U.; Schmitt, J.M. Colligative and Non-Colligative Freezing Damage to Thylakoid Membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1984, 769, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, E.E. Cryopreservation Theory. In Plant Cryopreservation: A Practical Guide; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2008; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.E. A Primer on Insect Cold-Tolerance. In Low Temperature Biology of Insects; 2010 ISBN 9780511675997.

- Marcantonini, G.; Bartolini, D.; Zatini, L.; Costa, S.; Passerini, M.; Rende, M.; Luca, G.; Basta, G.; Murdolo, G.; Calafiore, R.; et al. Natural Cryoprotective and Cytoprotective Agents in Cryopreservation: A Focus on Melatonin. Molecules 2022, 27, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariassen, K.E. The Mechanism of the Cryoprotective Effect of Glycerol in Beetles Tolerant to Freezing. J Insect Physiol 1979, 25, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toxopeus, J.; Koštál, V.; Sinclair, B.J. Evidence for Non-Colligative Function of Small Cryoprotectants in a Freeze-Tolerant Insect. proceedings of the royal society B 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worland, M.R.; Grubor-Lajšić, G.; Purać, J.; Thorne, M.A.S.; Clark, M.S. Cryoprotective Dehydration: Clues from an Insect. In Topics in Current Genetics; 2010; Vol. 21, pp. 147–163 ISBN 9783642124211.

- Olsson, T.; MacMillan, H.A.; Nyberg, N.; Staerk, D.; Malmendal, A.; Overgaard, J. Hemolymph Metabolites and Osmolality Are Tightly Linked to Cold Tolerance of Drosophila Species: A Comparative Study. Journal of Experimental Biology 2016, 219, 2504–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grgac, R.; Rozsypal, J.; Des Marteaux, L.; Štětina, T.; Koštál, V. Stabilization of Insect Cell Membranes and Soluble Enzymes by Accumulated Cryoprotectants during Freezing Stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolph, A.S.; Crowe, J.H. Membrane Stabilization during Freezing: The Role of Two Natural Cryoprotectants, Trehalose and Proline. Cryobiology 1985, 22, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K. E., Z.; E., K. Ice Nucleation and Antinucleation in Nature. Cryobiology 2000, 41, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.E.; Costanzo, J.P.; Mugnano, J.A. Regulation of Supercooling and Ice Nucleation in Insects. Eur J Entomol 1996, 93, 405–418. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.E.; Costanzo, J.P. Biological Ice Nucleation and Ice Distribution in Cold-Hardy Ectothermic Animals. Annu Rev Physiol 1998, 60, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberg, K.V.; Denholm, B. Mechanisms of Systemic Osmoregulation in Insects. Annu Rev Entomol 2024, 69, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chown, S.L.; Nicolson, S.W. Water Balance Physiology. In Insect Physiological Ecology; Oxford University Press, 2004; pp. 87–114.

- Miao, Z.Q.; Tu, Y.Q.; Guo, P.Y.; He, W.; Jing, T.X.; Wang, J.J.; Wei, D.D. Antioxidant Enzymes and Heat Shock Protein Genes from Liposcelis Bostrychophila Are Involved in Stress Defense upon Heat Shock. Insects 2020, 11, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sformo, T.; Walters, K.; Jeannet, K.; Wowk, B.; Fahy, G.M.; Barnes, B.M.; Duman, J.G. Deep Supercooling, Vitrification and Limited Survival to -100 C in the Alaskan Beetle Cucujus Clavipes Puniceus (Coleoptera: Cucujidae) Larvae. Journal of Experimental Biology 2010, 213, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, D.A. Supercooling and Freezing Tolerant Animals. Supercooling 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sømme, L. Supercooling and Winter Survival in Terrestrial Arthropods. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 1982, 73, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, J.G. Animal Ice-Binding (Antifreeze) Proteins and Glycolipids: An Overview with Emphasis on Physiological Function. Journal of Experimental Biology 2015, 218, 1846–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danks, H.V. Insect Adaptations to Cold and Changing Environments. Can Entomol 2009, 138, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, S.; Li, Y.; Nakano, K.; Tsumuki, H.; Goto, M. Seasonal Changes in Glycerol Content and Cold Hardiness in Two Ecotypes of the Rice Stem Borer, Chilo Suppressalis, Exposed to the Environment in the Shonai District, Japan. J Insect Physiol 2007, 53, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, L.; Overgaard, J. Cold Tolerance Is Linked to Osmoregulatory Function of the Hindgut in Locusta Migratoria. Journal of Experimental Biology 2018, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, K.B.; Storey, J.M. Freeze Tolerance: Constraining Forces, Adaptive Mechanisms. Can J Zool 1988, 66, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G.D.; Wang, S.; Fuller, B.J. Cryoprotectants: A Review of the Actions and Applications of Cryoprotective Solutes That Modulate Cell Recovery from Ultra-Low Temperatures. Cryobiology 2017, 76, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolac, L.K.; Lowe, J.L.; Koustas, G.; Grupen, C.G.; Sjöblom, C. Effect of Different Penetrating and Non-penetrating Cryoprotectants and Media Temperature on the Cryosurvival of Vitrified in Vitro Produced Porcine Blastocysts. Animal Science Journal 2018, 89, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, R.; Clulow, S.; Colyvas, K.; Mahony, M.; Clulow, J. Paradigm Shift in Frog Sperm Cryopreservation: Reduced Role for Non-Penetrating Cryoprotectants. Reproduction 2023, 165, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Li, P.H. Classification of Plant Cell Cryoprotectants. J Theor Biol 1986, 123, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.N.; Vagga, A. Cryopreservation: A Review Article. Cureus 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegg, D.E. Principles of Cryopreservation. In; 2007; pp. 39–57.

- Košťál, V.; Šimek, P. Overwintering Strategy in Pyrrhocoris Apterus (Heteroptera): The Relations between Life-Cycle, Chill Tolerance and Physiological Adjustments. J Insect Physiol 2000, 46, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Košt’ál, V.; Šlachta, M.; Šimek, P. Cryoprotective Role of Polyols Independent of the Increase in Supercooling Capacity in Diapausing Adults of Pyrrhocoris Apterus (Heteroptera: Insecta). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - B Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2001, 130, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towey, J.J.; Dougan, L. Structural Examination of the Impact of Glycerol on Water Structure. J Phys Chem B 2012, 116, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieme, H.; Oldenhof, H.; Wolkers, W.F. Mode of Action of Cryoprotectants for Sperm Preservation. Anim Reprod Sci 2016, 169, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, A.M.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Israelachvili, J.N.; Han, S. Communication: Contrasting Effects of Glycerol and DMSO on Lipid Membrane Surface Hydration Dynamics and Forces. J Chem Phys 2016, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick Williams, W.; Quinn, P.J.; Tsonev, L.I.; Koynova, R.D. The Effects of Glycerol on the Phase Behaviour of Hydrated Distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine and Its Possible Relation to the Mode of Action of Cryoprotectants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1991, 1062, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Roy, I. Trehalose and Protein Stability. Curr Protoc Protein Sci 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.G.; Wang, H.J.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cui, S.Y. Invertebrate Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase Gene: Genetic Architecture, Biochemistry, Physiological Function, and Potential Applications. Front Physiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.N. Trehalose - The Insect “Blood” Sugar. Adv In Insect Phys 2003, 31, 205–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, M.B.; Kotkar, H.M.; Joshi, R.S. Regulation of Trehalose Metabolism in Insects: From Genes to the Metabolite Window. Glycobiology 2023, 33, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-J. Mechanism of Neuroprotection by Trehalose: Controversy Surrounding Autophagy Induction. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corradini, D.; Strekalova, E.G.; Stanley, H.E.; Gallo, P. Microscopic Mechanism of Protein Cryopreservation in an Aqueous Solution with Trehalose. Sci Rep 2013, 3, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.S.; Thorne, M.A.S.; Purać, J.; Burns, G.; Hillyard, G.; Popović, Ž.D.; Grubor-Lajšić, G.; Worland, M.R. Surviving the Cold: Molecular Analyses of Insect Cryoprotective Dehydration in the Arctic Springtail Megaphorura Arctica (Tullberg). BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L.H.; Brockbank, K.G.M. Comparison of Electroporation and ChariotTM for Delivery of β-Galactosidase into Mammalian Cells: Strategies to Use Trehalose in Cell Preservation. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2011, 47, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Wang, S.; Duman, J.G.; Arifin, J.F.; Juwita, V.; Goddard, W.A.; Rios, A.; Liu, F.; Kim, S.-K.; Abrol, R.; et al. Antifreeze Proteins Govern the Precipitation of Trehalose in a Freezing-Avoiding Insect at Low Temperature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 6683–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyssa, R. Stephens Biochemistry of Trehalose Accumulation in the Spring Field Cricket, Gryllus Veletis, The University of Western Ontario, 2022.

- Yang, H.-J.; Cui, M.-Y.; Zhao, X.-H.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Hu, Y.-S.; Fan, D. Trehalose-6-Phosphate Synthase Regulates Chitin Synthesis in Mythimna Separata. Front Physiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Pan, Y.; Feng, Y.; Li, D.; Man, J.; Feng, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, H.; Chen, H. Role of Glucose in the Repair of Cell Membrane Damage during Squeeze Distortion of Erythrocytes in Microfluidic Capillaries. Lab Chip 2021, 21, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, K.P.; Templeton, G.H.; Hagler, H.K.; Willerson, J.T.; Buja, L.M. Effect of Glucose Availability on Functional Membrane Integrity, Ultrastructure and Contractile Performance Following Hypoxia and Reoxygenation in Isolated Feline Cardiac Muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1980, 12, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornwittawat, N.; Wang, S.; Banatlao, J.; Chung, M.; Velasco, E.; Duman, J.G.; Wen, X. Effects of Polyhydroxy Compounds on Beetle Antifreeze Protein Activity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 2009, 1794, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokulanathan, A.; Mo, H.; Park, Y. Glucose Influence Cold Tolerance in the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera Frugiperda via Trehalase Gene Expression. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 27334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STEINER, A.A.; PETENUSCI, S.O.; BRENTEGANI, L.G.; BRANCO, L.G.S. The Importance of Glucose for the Freezing Tolerance/Intolerance of the Anuran Amphibians Rana Catesbeiana and Bufo Paracnemis. Rev Bras Biol 2000, 60, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakó, I.; Pusztai, L.; Pothoczki, S. Outstanding Properties of the Hydration Shell around β- <scp>d</Scp> -Glucose: A Computational Study. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 20331–20337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesala, L.; Salminen, T.S.; Kostál, V.; Zahradníĉková, H.; Hoikkala, A. Myo-Inositol as a Main Metabolite in Overwintering Flies: Seasonal Metabolomic Profiles and Cold Stress Tolerance in a Northern Drosophilid Fly. Journal of Experimental Biology 2012, 215, 2891–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S. Cryopretectants and Their Usage in Cryopreservation Process. In Cryopreservation Biotechnology in Biomedical and Biological Sciences; IntechOpen, 2018.

- Watanabe, M. Cold Tolerance and Myo-Inositol Accumulation in Overwintering Adults of a Lady Beetle, Harmonia Axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Eur J Entomol 2002, 99, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, G.R.; Hendrix, D.L.; Salvucci, M.E. A Thermoprotective Role for Sorbitol in the Silverleaf Whitefly, Bemisia Argentifolii. J Insect Physiol 1998, 44, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, K.R.; Pan, Q.; Serianni, A.S.; Duman, J.G. Cryoprotectant Biosynthesis and the Selective Accumulation of Threitol in the Freeze-Tolerant Alaskan Beetle, Upis Ceramboides. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 16822–16831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.K.; Smith, J.S. Production of Threitol and Sorbitol by an Adult Insect: Association with Freezing Tolerance. Nature 1975, 258, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helou, B.; Ritchie, M.W.; MacMillan, H.A.; Andersen, M.K. Dietary Potassium and Cold Acclimation Additively Increase Cold Tolerance in Drosophila Melanogaster. J Insect Physiol 2024, 159, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, N.; Qin, D.; Xiao, C.; Lu, Y.; Guo, Z. Rapid Cold Hardening and Cold Acclimation Promote Cold Tolerance of Oriental Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel) by Physiological Substances Transformation and Cryoprotectants Accumulation. Bull Entomol Res 2023, 113, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, H.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Mehrabian, M. Cold Tolerance of the Tribolium Castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), under Different Thermal Regimes: Impact of Cold Acclimation. J Econ Entomol 2019, 112, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, G.; Zhang, R.; Dai, L.; Chen, H. Metabolism and Cold Tolerance of Chinese White Pine Beetle Dendroctonus Armandi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) during the Overwintering Period. Agric For Entomol 2017, 19, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Ji, R.; Ye, X. Physiological Characteristics and Cold Tolerance of Overwintering Eggs in Gomphocerus Sibiricus L. (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2021, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kučera, L.; Moos, M.; Štětina, T.; Korbelová, J.; Vodrážka, P.; Des Marteaux, L.; Grgac, R.; Hůla, P.; Rozsypal, J.; Faltus, M.; et al. A Mixture of Innate Cryoprotectants Is Key for Freeze Tolerance and Cryopreservation of a Drosophilid Fly Larva. Journal of Experimental Biology 2022, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanvand, H.; Izadi, H.; Mohammadzadeh, M. Overwintering Physiology and Cold Tolerance of the Sunn Pest, Eurygaster Integriceps, an Emphasis on the Role of Cryoprotectants. Front Physiol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, J.G. Thermal-Hysteresis-Factors in Overwintering Insects. J Insect Physiol 1979, 25, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.L.; Duman, J.G. The Role of the Thermal Hysteresis Factor in Tenebrio Molitor Larvae. Journal of Experimental Biology 1978, 74, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorv, J.S.H.; Rose, D.R.; Glick, B.R. Bacterial Ice Crystal Controlling Proteins. Scientifica (Cairo) 2014, 2014, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, B.S.; Glukhova, K.A.; Sokolova (Voronova), E.A.; Balalaeva, I. V.; Garbuzynskiy, S.O.; Finkelstein, A. V. Physics of Ice Nucleation and Antinucleation: Action of Ice-Binding Proteins. Biomolecules 2023, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeters, S.J.; Golbek, T.W.; Bregnhøj, M.; Drace, T.; Alamdari, S.; Roseboom, W.; Kramer, G.; Šantl-Temkiv, T.; Finster, K.; Pfaendtner, J.; et al. Ice-Nucleating Proteins Are Activated by Low Temperatures to Control the Structure of Interfacial Water. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białkowska, A.; Majewska, E.; Olczak, A.; Twarda-Clapa, A. Ice Binding Proteins: Diverse Biological Roles and Applications in Different Types of Industry. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John G Duman Antifreeze and Ice Nucleator Proteins in Terrestrial Arthropods. Annu Rev Physiol 2001, 63, 327–357. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, J.G. The Role of Macromolecular Antifreeze in the Darkling Beetle,Meracantha Contracta. Journal of Comparative Physiology ? B 1977, 115, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, J.G. Subzero Temperature Tolerance in Spiders: The Role of Thermal-Hysteresis-Factors. Journal of Comparative Physiology ? B 1979, 131, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baust, J.G.; Nishino, M. Freezing Tolerance in the Goldenrod Gall Fly (Eurosta Solidaginis). In Insects at Low Temperature; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1991; pp. 260–275. [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez, T.; Colinet, H. Cold Acclimation Triggers Lipidomic and Metabolic Adjustments in the Spotted Wing Drosophila Drosophila Suzukii (Matsumara). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2019, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, W. Cold Tolerance of Insects and Other Arthropods. Philosophical Transactions - Royal Society of London, B 1990, 326, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, N.; Moharramipour, S. Long-Term Cold Response in Overwintering Adults of Ladybird Hippodamia Variegata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). J Crop Prot 2013, 2, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hamedi, N.; Moharramipour, S.; Barzegar, M. Temperature-Dependent Chemical Components Accumulation in Hippodamia Variegata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) during Overwintering. Environ Entomol 2013, 42, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Izadi, H. Effects of Seasonal Acclimation on Cold Tolerance and Biochemical Status of the Carob Moth, Ectomyelois Ceratoniae Zeller, Last Instar Larvae. Bull Entomol Res 2014, 104, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajehoseini Saleh Abad, M.; Khani, A.; Izadi, H.; Sahebzadeh, N.; Samih, M.-A. Seasonal Changes in Supercooling Capacity and Main Polyols in Overwintering Adults of Acrosternum Millierei (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Int J Pest Manag 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabir, M.; Izadi, H.; Mahdian, K. The Supercooling Point Depression Is the Leading Cold Tolerance Strategy for the Variegated Ladybug, [Hippodamia Variegata (Goezel)]. Front Physiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, R.; Depciuch, J.; Kapusta, I.; Kisała, J.; Durak, T. Changes in Chemical Composition and Accumulation of Cryoprotectants as the Adaptation of Anholocyclic Aphid Cinara Tujafilina to Overwintering. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Iqbal, J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-W.; Hu, J.; Du, Y.-Z. Integrated Transcriptional and Biochemical Profiling Suggests Mechanisms Associated with Rapid Cold Hardening in Adult Liriomyza Trifolii (Burgess). Sci Rep 2024, 14, 24033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, N.; Qin, D.; Xiao, C.; Lu, Y.; Guo, Z. Rapid Cold Hardening and Cold Acclimation Promote Cold Tolerance of Oriental Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Dorsalis (Hendel) by Physiological Substances Transformation and Cryoprotectants Accumulation. Bull Entomol Res 2023, 113, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayari, S. Cryoprotectants in Overwintering Larvae of Leopard Moth, Zeuzera Pyrina (Lepidoptera: Cossidae), Collected from Northwestern Iran. J Crop Prot 2022, 11, 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Teets, N.M.; Denlinger, D.L. Physiological Mechanisms of Seasonal and Rapid Cold-Hardening in Insects. Physiol Entomol 2013, 38, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teets, N.M.; Gantz, J.D.; Kawarasaki, Y. Rapid Cold Hardening: Ecological Relevance, Physiological Mechanisms and New Perspectives. J Exp Biol 2020, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhu, D.-H. Effects of Rapid Cold-Hardening and Cold Acclimation on Egg Survival and Cryoprotectant Contents in Ceracris Kiangsu (Orthoptera: Arcypteridae). Ann Entomol Soc Am 2023, 116, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.E.; Chen, C.-P.; Denlinger, D.L. A Rapid Cold-Hardening Process in Insects. Science (1979) 1987, 238, 1415–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaei, M.; Izadi, H.; Šimek, P.; Koštál, V. Overwintering Biology and Limits of Cold Tolerance in Larvae of Pistachio Twig Borer, Kermania Pistaciella. Bull Entomol Res 2016, 106, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poikela, N.; Tyukmaeva, V.; Hoikkala, A.; Kankare, M. Multiple Paths to Cold Tolerance: The Role of Environmental Cues, Morphological Traits and the Circadian Clock Gene Vrille. BMC Ecol Evol 2021, 21, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Burg, K.R.L.; Bozorgi, Y.; Gyte, K.; Roe, A.D.; Marshall, K.E. Plasticity in Cryoprotectant Synthesis Involves Coordinated Shunting Away from Pyruvate Production 2024.

- Moos, M.; Korbelová, J.; Štětina, T.; Opekar, S.; Šimek, P.; Grgac, R.; Koštál, V. Cryoprotective Metabolites Are Sourced from Both External Diet and Internal Macromolecular Reserves during Metabolic Reprogramming for Freeze Tolerance in Drosophilid Fly. Metabolites 2022, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.D.; Bonnett, T.R.; Keeling, C.I.; Huber, D.P.W. Seasonal Shifts in Accumulation of Glycerol Biosynthetic Gene Transcripts in Mountain Pine Beetle, Dendroctonus Ponderosae Hopkins (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), Larvae. PeerJ 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.G. Cryoprotectant Systems and Cold Tolerance of Insects Inhabiting Central Yakutia (Russian Far East). Eur J Entomol 2016, 113, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Wharton, D.A. Infective Juveniles of the Entomopathogenic Nematode, Steinernema Feltiae Produce Cryoprotectants in Response to Freezing and Cold Acclimation. PLoS One 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, P.; Paakkonen, T.; Eerilä, H.; Puukka, K.; Riikonen, J.; Lehto, V.; Mustonen, A. Freezing Tolerance and Low Molecular Weight Cryoprotectants in an Invasive Parasitic Fly, the Deer Ked ( Lipoptena Cervi ). J Exp Zool A Ecol Genet Physiol 2012, 317A, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, M.; Izadi, H. Cold Acclimation of Trogoderma Granarium Everts Is Tightly Linked to Regulation of Enzyme Activity, Energy Content and Ion Concentration. bioRxiv 2018. [CrossRef]

- Soudi, Sh.; Moharramipour, S. Cold Tolerance and Supercooling Capacity in Overwintering Adults of Elm Leaf Beetle Xanthogaleruca Luteola (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Environ Entomol 2012, 40, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudi, S. , Moharramipour, S., Barzegar, M., Atapour, M. Cryoprotectant Contents of Overwintering Elm Leaf Beetle Xanthogaleruca Luteola. J. Entomol. Soc. Iran 2011, 31, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Soudi, S.; Moharramipour, S. Seasonal Patterns of the Thermal Response in Relation to Sugar and Polyol Accumulation in Overwintering Adults of Elm Leaf Beetle, Xanthogaleruca Luteola (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J Therm Biol 2012, 37, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.S.; Rasmann, S.; Li, M.; Guo, J.Y.; Chen, H.S.; Wan, F.H. Cold Temperatures Increase Cold Hardiness in the Next Generation Ophraella Communa Beetles. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boychuk, E.C.; Smiley, J.T.; Dahlhoff, E.P.; Bernards, M.A.; Rank, N.E.; Sinclair, B.J. Cold Tolerance of the Montane Sierra Leaf Beetle, Chrysomela Aeneicollis. J Insect Physiol 2015, 81, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Tanaka, K. Cold Tolerance Strategy of the Freeze-Intolerant Chrysomelid, Aulacophora Nigripennis (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), in Warm-Temperate Regions. Eur J Entomol 1999, 96, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Saeidi, M.; Moharramipour, S. Physiology of Cold Hardiness, Seasonal Fluctuations, and Cryoprotectant Contents in Overwintering Adults of Hypera Postica (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ Entomol 2017, 46, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koštál, V.; Miklas, B.; Doležal, P.; Rozsypal, J.; Zahradníčková, H. Physiology of Cold Tolerance in the Bark Beetle, Pityogenes Chalcographus and Its Overwintering in Spruce Stands. J Insect Physiol 2014, 63, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Chang, Y.D.; Kim, Y.G. Trehalose, a Major Sugar Cryoprotectant of the Overwintering Rice Water Weevil, Lissorhoptrus Oryzophilus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J Asia Pac Entomol 2002, 5, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnot, G.; Peypelut, L.; Gérard Febvay; Lavenseau, L. ; Fleurat-Lessard, F.; Fields, P.G. The Effect of Cold Acclimation and Deacclimation on Cold Tolerance, Trehalose and Free Amino Acid Levels in Sitophilus Granarius and Cryptolestes Ferrugineus (Coleoptera). J Insect Physiol 1998, 44, 955–965. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, J.A.; Bonnett, T.; Pitt, C.; Spooner, L.J.; Fraser, J.; Yuen, M.M.S.; Keeling, C.I.; Bohlmann, J.; Huber, D.P.W. Gene Expression Analysis of Overwintering Mountain Pine Beetle Larvae Suggests Multiple Systems Involved in Overwintering Stress, Cold Hardiness, and Preparation for Spring Development. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Pei, J.; Chen, X.; Shi, F.; Bao, Z.; Hou, Q.; Zhi, L.; Zong, S.; Tao, J. Cold Tolerance and Metabolism of Red-Haired Pine Bark Beetle Hylurgus Ligniperda (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) during the Overwintering Period. J Econ Entomol 2024, 117, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, R.A.; Tesar, D. Cold-Hardiness of the Arctic Beetle, Pytho Americanus Kirby Coleoptera, Pythidae (Salpingidae). J Insect Physiol 1980, 26, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosthwaite, J.C.; Sobek, S.; Lyons, D.B.; Bernards, M.A.; Sinclair, B.J. The Overwintering Physiology of the Emerald Ash Borer, Agrilus Planipennis Fairmaire (Coleoptera: Buprestidae). J Insect Physiol 2011, 57, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xu, L.; Tian, B.; Tao, J.; Wang, J.; Zong, S. Cold Hardiness of Asian Longhorned Beetle (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Larvae in Different Populations. Environ Entomol 2014, 43, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Košťál, V.; Šimek, P. Dynamics of Cold Hardiness, Supercooling and Cryoprotectants in Diapausing and Non-Diapausing Pupae of the Cabbage Root Fly, Delia Radicum L. J Insect Physiol 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, N.L.; Moqueet, N.; Shapiro, C.A. Evidence for a Novel Cryoprotective Protein from Freeze-Tolerant Larvae of the Goldenrod Gall Fly Eurosta Solidaginis. Cryobiology 2007, 54, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, K.E.; Sinclair, B.J. Repeated Freezing Induces a Trade-off between Cryoprotection and Egg Production in the Goldenrod Gall Fly, Eurosta Solidaginis. Journal of Experimental Biology 2018, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.A.; Benoit, J.B.; Denlinger, D.L.; Rivers, D.B. Stress-Induced Accumulation of Glycerol in the Flesh Fly, Sarcophaga Bullata: Evidence Indicating Anti-Desiccant and Cryoprotectant Functions of This Polyol and a Role for the Brain in Coordinating the Response. J Insect Physiol 2006, 52, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, S.; Bubacco, L.; Beltramini, M. SEASONAL VARIATION OF TREHALOSE AND GLYCEROL CONCENTRATIONS IN WINTER SNOW-ACTIVE INSECTS; 2008; Vol. 29;

- BLOCK, W.; ERZINCLIOGLU, Y.Z.; WORLAND, M.R. Cold Resistance in All Life Stages of Two Blowfly Species (Diptera, Calliphoridae). Med Vet Entomol 1990, 4, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, M.; Park, Y. Cold Tolerance Strategies of the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera Frugiperda (Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, M.; Sajjadian, S.M.; Park, Y. Glycerol Biosynthesis Plays an Essential Role in Mediating Cold Tolerance the Red Imported Fire Ant, Solenopsis Invicta. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2022, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.H.; Lee, D. Suppression of Glycerol Biosynthesis-related Genes Decreases the Effect of Rapid Cold Hardening in <scp> Helicoverpa Assulta </Scp>. Entomol Res 2022, 52, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atapour, M.; Moharramipour, S. Cold Hardiness Process of Beet Armyworm Larvae, Spodoptera Exigua ( Lepidoptera : Noctuidae ). 2014, 3, 147–158.

- Sun, M.; Tang, X.-T.; Lu, M.-X.; Yan, W.-F.; Du, Y.-Z. Cold Tolerance Characteristics and Overwintering Strategy of Sesamia Inferens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Florida Entomologist 2014, 97, 1544–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillyboeuf, N.; Anglade, P.; Lavenseau, L.; Peypelut, L. Cold Hardiness and Overwintering Strategy of the Pink Maize Stalk Borer, Sesamia Nonagrioides Lef (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae). Oecologia 1994, 99, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreadis, S.S.; Vryzas, Z.; Papadopoulou-Mourkidou, E.; Savopoulou-Soultani, M. Cold Tolerance of Field-Collected and Laboratory Reared Larvae of Sesamia Nonagrioides (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Cryo-Letters 2011, 32, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- PULLIN, A.S.; BALE, J.S.; FONTAINE, X.L.R. Physiological Aspects of Diapause and Cold Tolerance during Overwintering in Pieris Brassicae. Physiol Entomol 1991, 16, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanic, B.; Jovanovic-Galovic, A.; Blagojevic, D.P.; Grubor-Lajsic, G.; Worland, R.; Spasic, M.B. Cold Hardiness in Ostrinia Nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae): Glycerol Content, Hexose Monophosphate Shunt Activity, and Antioxidative Defense System. Eur J Entomol 2004, 101, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadis, S.S.; Vryzas, Z.; Papadopoulou-Mourkidou, E.; Savopoulou-Soultani, M. Age-Dependent Changes in Tolerance to Cold and Accumulation of Cryoprotectants in Overwintering and Non-Overwintering Larvae of European Corn Borer Ostrinia Nubilalis. Physiol Entomol 2008, 33, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojić, D.; Popović, Ž.D.; Orčić, D.; Purać, J.; Orčić, S.; Vukašinović, E.L.; Nikolić, T. V.; Blagojević, D.P. The Influence of Low Temperature and Diapause Phase on Sugar and Polyol Content in the European Corn Borer Ostrinia Nubilalis (Hbn.). J Insect Physiol 2018, 109, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, A.; Moharramipour, S.; Barzegar, M. Cold Tolerance and Trehalose Accumulation in Overwintering Larvae of the Codling Moth, Cydia Pomonella (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Eur J Entomol 2007, 104, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozsypal, J.; Koštál, V.; Zahradníčková, H.; Šimek, P. Overwintering Strategy and Mechanisms of Cold Tolerance in the Codling Moth (Cydia Pomonella). PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.G. Relationships between Cold Hardiness, and Ice Nucleating Activity, Glycerol and Protein Contents in the Hemolymph of Caterpillars, Aporia Crataegi L. Cryo-Letters 2012, 33, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, K.E.; Sinclair, B.J. The Relative Importance of Number, Duration and Intensity of Cold Stress Events in Determining Survival and Energetics of an Overwintering Insect. Funct Ecol 2015, 29, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassmann, J.E.; Lee, R.E.; Rojas, R.R.; Baust, J.G. Caste and Sex Differences in Cold-Hardiness in the Social Wasps,Polistes Annularis AndP. Exclamans (Hymenoptera: Vespidae). Insectes Soc 1984, 31, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sømme, L. EFFECTS OF GLYCEROL ON COLD-HARDINESS IN INSECTS. Can J Zool 1964, 42, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Ji, R.; Ye, X. Physiological Characteristics and Cold Tolerance of Overwintering Eggs in Gomphocerus Sibiricus L. (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 2021, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toxopeus, J.; Lebenzon, J.E.; McKinnon, A.H.; Sinclair, B.J. Freeze Tolerance of Cyphoderris Monstrosa (Orthoptera: Prophalangopsidae). Canadian Entomologist 2016, 148, 668–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, F.; Moharramipour, S.; Barzegar, M. Seasonal Patterns of Cold Hardiness and Cryoprotectant Profiles in <I>Brevicoryne Brassicae</I> (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Environ Entomol 2012, 41, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Diaz, R.; Laine, R.A. Physiology of Crapemyrtle Bark Scale, Acanthococcus Lagerstroemiae (Kuwana), Associated with Seasonally Altered Cold Tolerance. J Insect Physiol 2019, 112, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, R.; Izadi, H.; Mahdian, K. Energy Allocation Changes in Overwintering Adults of the Common Pistachio Psylla, Agonoscena Pistaciae Burckhardt & Lauterer (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Neotrop Entomol 2012, 41, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B.J. Cryoprotectants: The Essential Antifreezes to Protect Life in the Frozen State. Cryo-Letters 2004, 25, 375–388. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, G.D.; Wang, S.; Fuller, B.J. Cryoprotectants: A Review of the Actions and Applications of Cryoprotective Solutes That Modulate Cell Recovery from Ultra-Low Temperatures. Cryobiology 2017, 76, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Cold tolerance | Cold hardiness |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The ability of insects to survive and function at low temperatures in the short term. | The ability to resist long-term exposure to low temperatures and survive freezing temperatures |

| Freezing | May or may not involve freezing | Necessarily involves dealing with freezing |

| Mechanisms | Behavioral and physiological (supercooling and cryoprotectants) adaptations. | Involves specialized adaptations such as cold acclimation, rapid cold hardening freeze avoidance, and freeze tolerance |

| Feature | Ice nucleating proteins (INPs) | Antifreeze proteins (AFPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary function | Induce ice formation | Prevent ice formation |

| Mechanism of action | Promote nucleation at high subzero temperatures | Bind to existing ice crystals to inhibit growth |

| Role in cold tolerance | Control location and timing of ice formation | Stabilize cells and prevent recrystallization |

| Adaptation strategy | Essential for freeze-tolerant species | Common in freeze-avoiding species |

| Seasonal variation | May be removed or masked during winter | Often expressed year-round to prevent freezing |

| Order | Family | Species | Predominant cryoprotectant | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coleoptera | Dermestidae | Trogoderma granarium | Trehalose, sorbitol, myo-inositol, glucose | [125] |

| Chrysomelidae | Xanthogaleruca luteola | Myo-inositol, trehalose, glucose | [126,127,128] | |

| Ophraella communa | Glycerol | [129] | ||

| Chrysomela aeneicollis | Glycerol | [130] | ||

| Aulacophora nigripennis | Myo-inositol | [131] | ||

| Galerucella nymphaea | Glycerol | [122] | ||

| Chrysolina graminis | Glycerol | |||

| Curculionidae | Hypera postica | Sorbitol, glycerol, glucose, trehalose | [132] | |

| Pityogenes chalcographus | Glycerol | [133] | ||

| Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus | Trehalose | [134] | ||

| Sitophilus granarius | Trehalose | [135] | ||

| Dendroctonus ponderosae | Glycerol | [136] | ||

| Upis ceramboides | Sorbitol, threitol | [83] | ||

| Hylurgus ligniperda | Sorbitol, trehalose, glycerol | [137] | ||

| Tenebrionidae | Tribolium castaneum | Trehalose, myo-inositol | [87] | |

| Pythidae | Pytho depressus | Glycerol | [30] | |

| P. americanus | Glycerol | [138] | ||

| Buprestidae | Agrilus planipennis | Glycerol | [139] | |

| Laemophloeidae | Cryptolestes ferrugineus | Trehalose | [135] | |

| Cerambycidae | Anoplophora glabripennis | Glycerol, glucose, sorbitol, trehalose | [140] | |

| Coccinellidae | Hippodamia variegata | Trehalose, glucose, myo-inositol | [104,105] | |

| Harmonia axyridis | Myo-inositol | [81] | ||

| Diptera | Anthomyiidae | Delia antiqua | Trehalose, glucose, myo-inositol | [141] |

| Drosophilidae | Drosophila melanogaster | Myo-inositol, proline | [79] | |

| Tephritidae | Eurosta solidagnis | Carbohydrates and proteins | [142,143] | |

| Sarchophagidae | Sarcophaga bullata | Glycerol | [144] | |

| Limoniidae | Chionea sp. | Trehalose | [145] | |

| Tephritidae | Bactrocera dorsalis | Proteins, glycerol, trehalose | [86] | |

| Hippoboscidae | Lipoptena cervi | Proline, arginine, asparagine, cystine, glutamate, glutamine | [124] | |

| Sarcophagidae | Sarcophaga bullata | Glycerol | [144] | |

| Calliphoridae | Calliphora vicina | Glucose | [146] | |

| C. vomitoria | ||||

| Lepidoptera | Noctuidae | Spodoptera frugiperda | Glycerol | [147,148] |

| Chilo suppressalis | Glycerol | [31] | ||

| Helicoverpa assulta | Glycerol | [149] | ||

| Ectomyelois ceratoniae | Trehalose, myo-inositol | [106] | ||

| Arimania comaroffi | Trehalose, myo-inositol, sorbitol | [9] | ||

| Spodoptera exigua | Trehalose, glycerol, myo-inositol | [150] | ||

| Sesamia inferens | Trehalose, glycerol, glucose, fructose, myo-inositol | [151] | ||

| S. nonagrioides | Trehalose, glycerol | [152,153] | ||

| Pieris brassicae | Trehalose, myo-inositol, sorbitol | [154] | ||

| Ostrinia nubilalis | Trehalose, glycerol | [155,156,157] | ||

| Cydia pomonella | Trehalose, glucose, glycerol, | [158,159] | ||

| Aporia crataegi | Glycerol | [160] | ||

| Choristoneura fumiferana | Glycerol | [161] | ||

| Hymenoptera | Formicidae | Solenopsis invicta | Glycerol | [147,148] |

| Polistes exclamans | Glycerol | [31,162] | ||

| Braconidae | Bracon cephi | Glycerol | [163] | |

| Orthoptera | Gryllidae | Gryllus veletis | Glycerol7 | [31,162] |

| Acrididae | Gomphocerus sibiricus | Glycerol, fructose, sorbitol, amino acids | [164] | |

| Prophalangopsidae | Cyphoderris monstrosa | Trehalose, proline | [165] | |

| Heteroptera | Aphididae | Schizaphis graminum | Trehalose, glucose | [166] |

| Eriococcidae | Acanthococcus lagerstroemiae | D-mannitol | [167] | |

| Scutelleridae | Eurygaster integriceps | Glycerol, trehalose | [91] | |

| Psyllidae | Agonoscena pistaciae | Trehalose, myoinositol, sorbitol | [168] | |

| Aphididae | Cinara tujafilina | Glucose, trehalose, mannitol, myo-inositol, glycerol | [109] |

| Strategy | Trigger | Example Species | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid (Anticipatory) | Photoperiod/temperature | Goldenrod gall fly, Eurosta solidaginis, Fire-colored beetle, Dendroides canadensis | Temperate seasonal |

| Incremental (Acclimatory) | Gradual cooling | Woolly bear caterpillar, Pyrrharctia isabella, Lady beetle, Coccinella septempunctata | Unpredictable cold |

| Basal (Constitutive) | Genetic adaptation | Antarctic midge, Belgica antarctica, Arctic springtail, Megaphorura arctica | Polar/alpine |

| Feature | Insects | Other ectotherms |

|---|---|---|

| Cryoprotectant diversity | High (polyols, amino acids, sugars) | Moderate (mainly glycerol, glucose) |

| Freeze tolerance mechanism | Intracellular freezing (select species) | Extracellular freezing only |

| Cryoprotectant sources | Internal reserves and dietary intake | Predominantly glycogen-derived |

| Adaptation | Rapid accumulation, diapause-linked | Gradual accumulation, seasonal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).