1. Introduction

Aphids are among the most economically important pests in cereal crops due to their role in vectoring plant viruses [

1]. Bird cherry-oat aphid (

Rhopalosiphum padi L.; Hemiptera: Aphididae) and English grain aphid (

Sitobion avenae Fabricius; Hemiptera: Aphididae) vector barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) in cereal crops. Estimates suggest that BYDV may be responsible for yield losses of up to 84% in wheat and 64% in barley. The impact on yield is mainly as a result of reduced grain number [

2]. Current BYDV management strategies include foliar pyrethroid insecticide applications and delayed sowing to avoid peak aphid migration events [

3]. However, insecticide use is associated with negative impacts on non-target organisms and the evolution of resistance in the target organism to active ingredients that reduces the efficacy of key plant protection products [e.g. 4,5]. Meanwhile, delayed sowing can result in reduced yields [

6]. Reduced yields are due to low temperatures during crop vegetative growth and shortened duration of various phases of crop development.

Exploiting the genetic diversity found within different wheat varieties offers an alternative to current controls for managing both aphid pests and virus transmission [

7,

8]. Host plant genetics influence insect performance parameters, which may reduce aphid infestations through increased resistance [

9]. Aphid performance typically focuses on mean relative growth rate (MRGR) and intrinsic rate of increase (

rm) for individual aphids to assess relative resistance/susceptibility across host plants [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Intrinsic rate of increase describes the rate at which a population changes size per unit of time in the absence of limiting factors such as predation or resource competition [

14]. The

rm value integrates both reproductive output and survival probabilities to provide a comprehensive measure of population growth, which is strongly influenced by the nutritional quality of the host plant [

15,

16]. On the other hand, MRGR focuses on biomass changes in individual aphids over a specific period by calculating the increase in an individual's weight relative to its initial size over time [

17]. Thus, MRGR is a measure of how efficiently an individual aphid grows, which can influence developmental speed and, consequently, reproductive timing, indirectly affecting population growth.

Confining individual aphids onto specific plant parts using a clip-cages is a common practice in aphid performance studies to facilitate data collection and avoid losing individuals during experiments [

7,

18,

19]. Although effective at containing aphids, clip cages have unintended consequences on their biology that may impact any conclusions drawn from performance studies [

20]. For instance, as clip cages are designed to restrict aphid movement it prevents an individual from choosing a feeding site. This is important as each aphid species may preferentially feed on specific plant parts [

21]. Attaching and detaching clip cages during data collection may also damage plant tissue and upregulate defence responses in the host plant, indirectly affecting aphid development or limit plant physiology in other ways [

22,

23]. To address the effects of confinement and wheat variety on aphid performance, the present study measured the intrinsic rate of increase and mean relative growth rate of the bird cherry-oat aphid and English grain aphid on five different wheat varieties and one barley variety using two different confinement methods. Through this study, we aim to determine the importance of methods used for aphid research investigating host plant resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Plants were grown under glasshouse conditions at Harper Adams University (52.777385, -2.427895) (mean temperature: 20 ± 5 °C/10 ± 5 °C day/night; 16h:8h light:dark photoperiod). Wheat (

Triticum aestivum L.) and spring barley (

Hordeum vulgare L.) seeds from each tested variety were sown 1 cm deep into 9 x 9 cm pots (Teku, Poeppelmann GmbH, Lohne, Germany) filled with peat-free John Innes No. 2 compost (Sylva Grow®, Melcourt, Tetbury, UK). Plants were grown in 60 x 60 x 60 cm fine nylon mesh (160 μm) cages (BugDorm-6E Insect Rearing Cage, Taichung, Taiwan) with a tray (58 x 58 cm) placed underneath the pots for watering until the plants had reached BBCH Growth Stage 12 (GS12) [

24] before being used for experiments. The wheat varieties used in this study were selected to include a range of end uses and parental lineages (

Table 1). Spring barley (var. Planet) was used to rear all aphid populations and included in experiments as a control to account for possible influence of previous generations feeding experience [

25].

2.2. Aphid Populations and Age-Synchronised Cohorts

English grain aphid (Sitobion avenae) and bird cherry oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi) were established by collecting 10 individuals of each species from cereal fields located at Harper Adams University and transferring them to potted spring barley (var. Planet) seedlings. Aphid infested barley plants were then placed in insect cages (47.5 x 47.5 x 47.5 cm) (Bugdorm-4 Insect Rearing Cage, Taichung, Taiwan) separated by species and housed in a plant growth room (Fitotron® Weiss Technik, Loughborough, UK) maintained at 18 °C and 60 % relative humidity under a 16:8 light:dark photoperiod. Population maintenance was carried out on a weekly basis by replacing heavily infested barley plants with clean plants. Each population of aphids was maintained in this way for over 10 generations before being used in experiments (i.e., approximately 10 to 12 weeks).

Age-synchronised aphid cohorts were produced prior to use in experiments in order to standardise the fitness of aphids at the start of each experiment. Aphid cohorts were established by transferring 20 adult aphids from the stock populations to clean barley plants (var. Planet) at BBCH GS12 in a new cage (47.5 x 47.5 x 47.5 cm) and left to larviposit for 24 hours. Adult aphids were then removed and only first instar nymphs were left to develop under the same conditions as stock populations until they had become adults.

2.3. Experimental Design

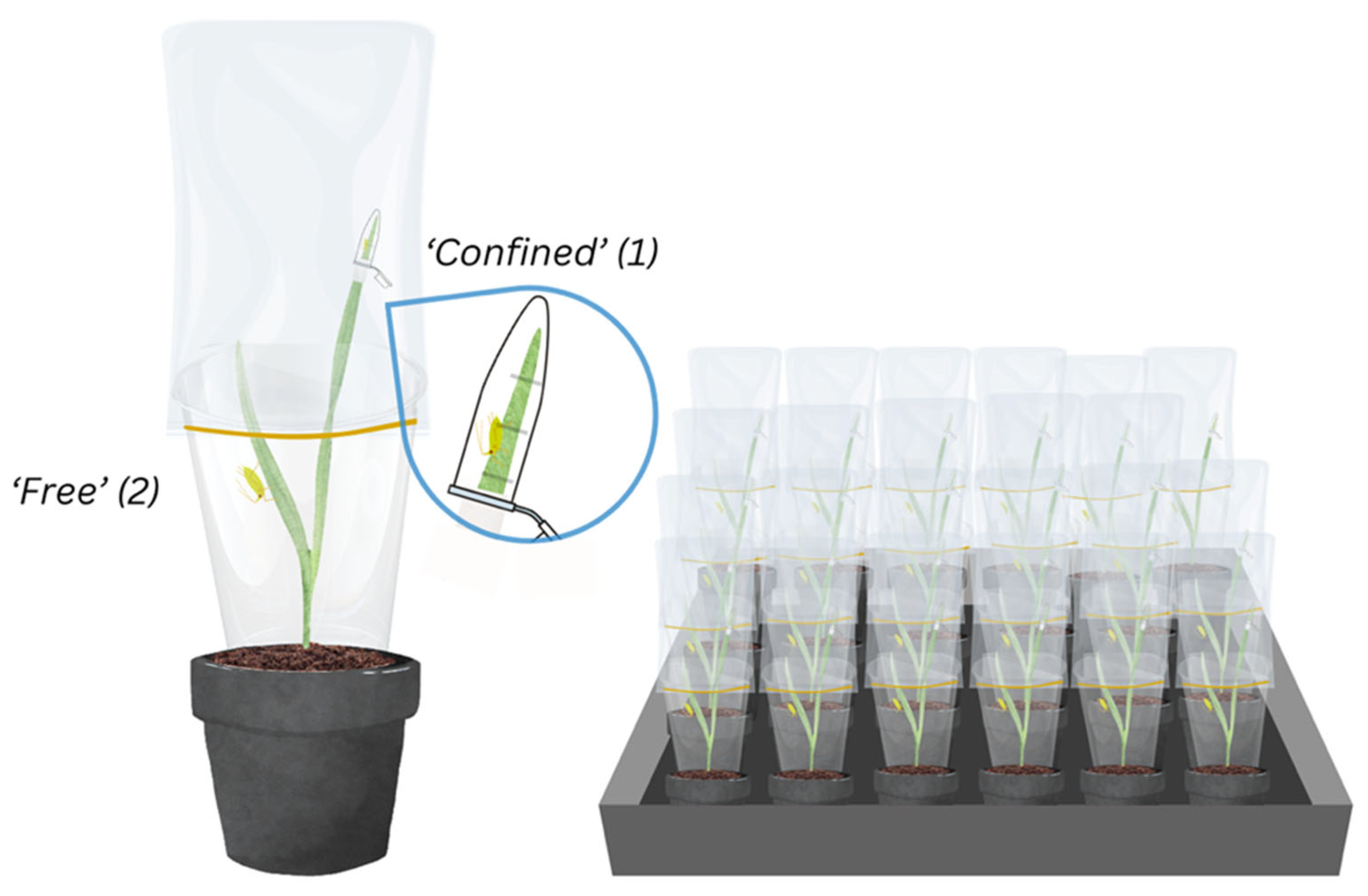

Each aphid species These aphid cohorts was studied separately in consecutive experiments to avoid cross contamination and both experiments were completed in a plant growth room (Fitotron® Weiss Technik, Loughborough, UK) maintained at 20°C and 60 % relative humidity under a 16:8 light:dark photoperiod. Two confinement methods, (‘confined’ and ‘free’) were simultaneously tested on each experimental plant to facilitate direct comparison. Adults from the age-synchronised cohorts were individually placed on each experimental plant, confined to a leaf section inside an open 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) sealed with ¼ of a cotton pad (‘confined’) or placed on whole plants covered with a clear plastic cylinder (13 cm in height, 7 cm in diameter at the top, and 5.5 cm in diameter at the bottom) mounted with a fine mesh organza bag at the top (18 x 13 cm) (‘free’) (

Figure 1). The leaf used for aphid confinement was randomly selected for each plant using a random number generator. Adults were left to larviposit for a 24-hour period on experimental plant and after 24-hours the adult aphids and all but one first instar nymph was removed from each plant. Nymphs removed from these plants were weighed (XPR10/M Microbalance, Mettler Toledo, Columbus, USA) in groups of ten to obtain a mean first-instar nymph weight. Each experimental nymph was carefully removed from the plant using a fine paintbrush (size 000) on day five, individually weighed and then returned to the same plant and position from which it was taken. These aphids were monitored every day to track their development using exuviae. After reaching adulthood, each aphid was monitored every one to two days for a period equal to its development time, and the number of offspring was recorded and removed periodically. To evaluate aphid performance in the different host plants and confinement conditions, multiple biological parameters were measured and are described in

Table 2, adapted from [

25,

26]. Five blocks with six replicates per treatment (variety) and two methods was carried out using a complete randomised block design for each aphid species.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were first checked for normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and homoscedasticity (Levene’s). Because all datasets satisfied these assumptions, or were sufficiently close, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) were fitted using the lme4 package [

29], with ‘Replicate’ as a random effect and ‘Variety’ and ‘Method’ as fixed effects. Separate models were fitted for each response variable (MRGR and

rm), initially including the Variety × Method interaction. Likelihood-ratio tests compared the full (interaction) model against the reduced (no-interaction) model, which was non-significant in all cases and so final inferences were based on the reduced models. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were carried out using the emmeans package with Sidak adjustment [

30]. All analyses were carried out using R (version 4.4.1).

3. Results

3.1. English Grain Aphid

3.1.1. Mean Relative Growth Rate (MRGR)

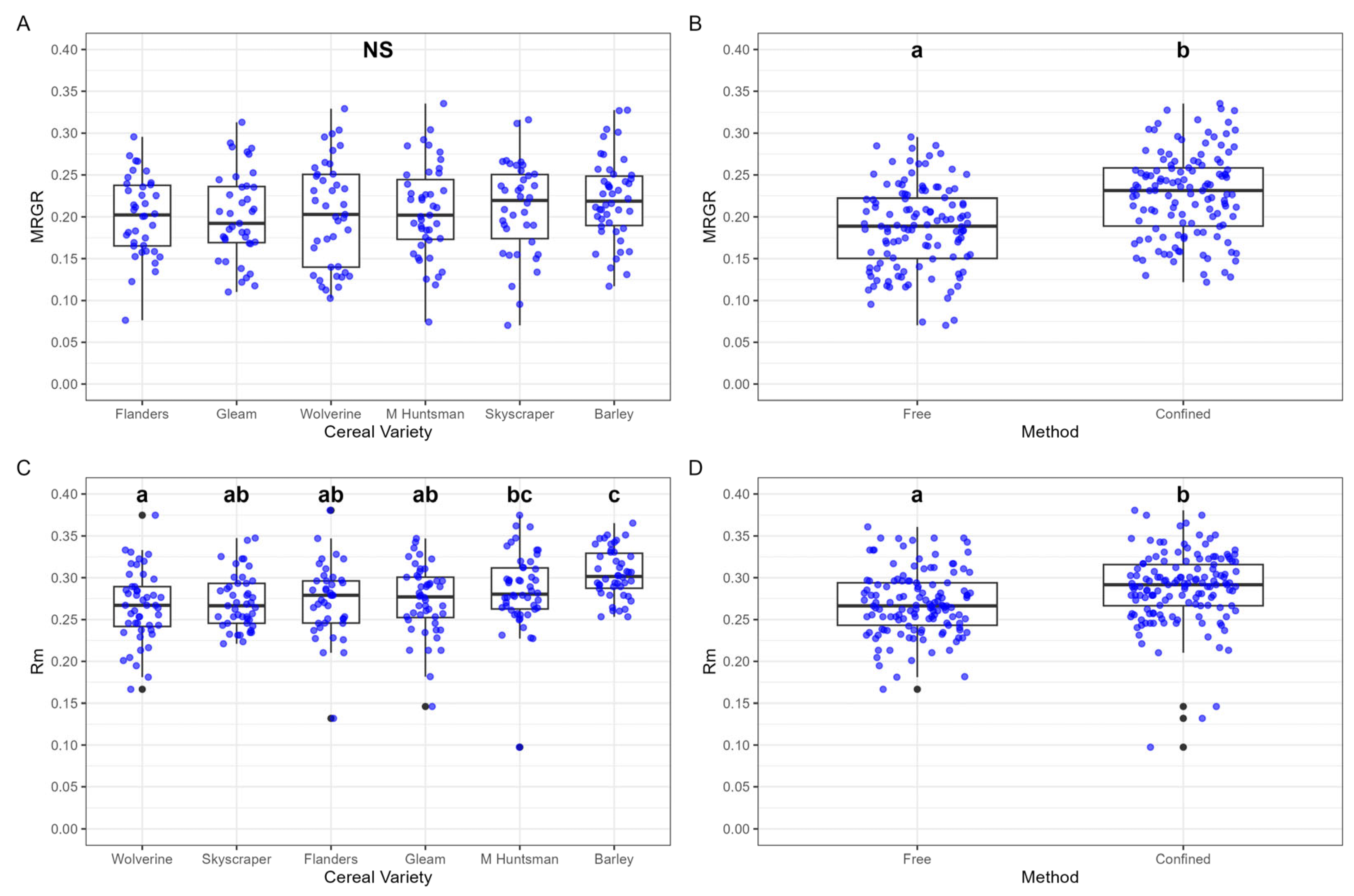

No differences were found in MRGR between cereal varieties (

Figure 2A). Confinement method, however, had a significant effect, with a higher MRGR recorded for ‘confined’ aphids MRGR (0.227 ± 0.008) compared to ‘free’ aphids (0.185 ± 0.008) (

Figure 2B).

3.1.2. Intrinsic Rate of Increase (rm)

Significant differences were observed between cereal varieties. The highest

rm (0.305 ± 0.004) was recorded for aphids feeding on barley, whilst the lowest

rm (0.266 ± 0.006) was recorded on Wolverine (

Figure 2C). Confinement also had a significant effect on

rm, with higher values recorded for ‘confined’ aphids (0.288 ± 0.003) compared to ‘free’ aphids (0.268 ± 0.003).

3.2. Bird Cherry-Oat Aphid

3.2.1. Mean Relative Growth Rate (MRGR)

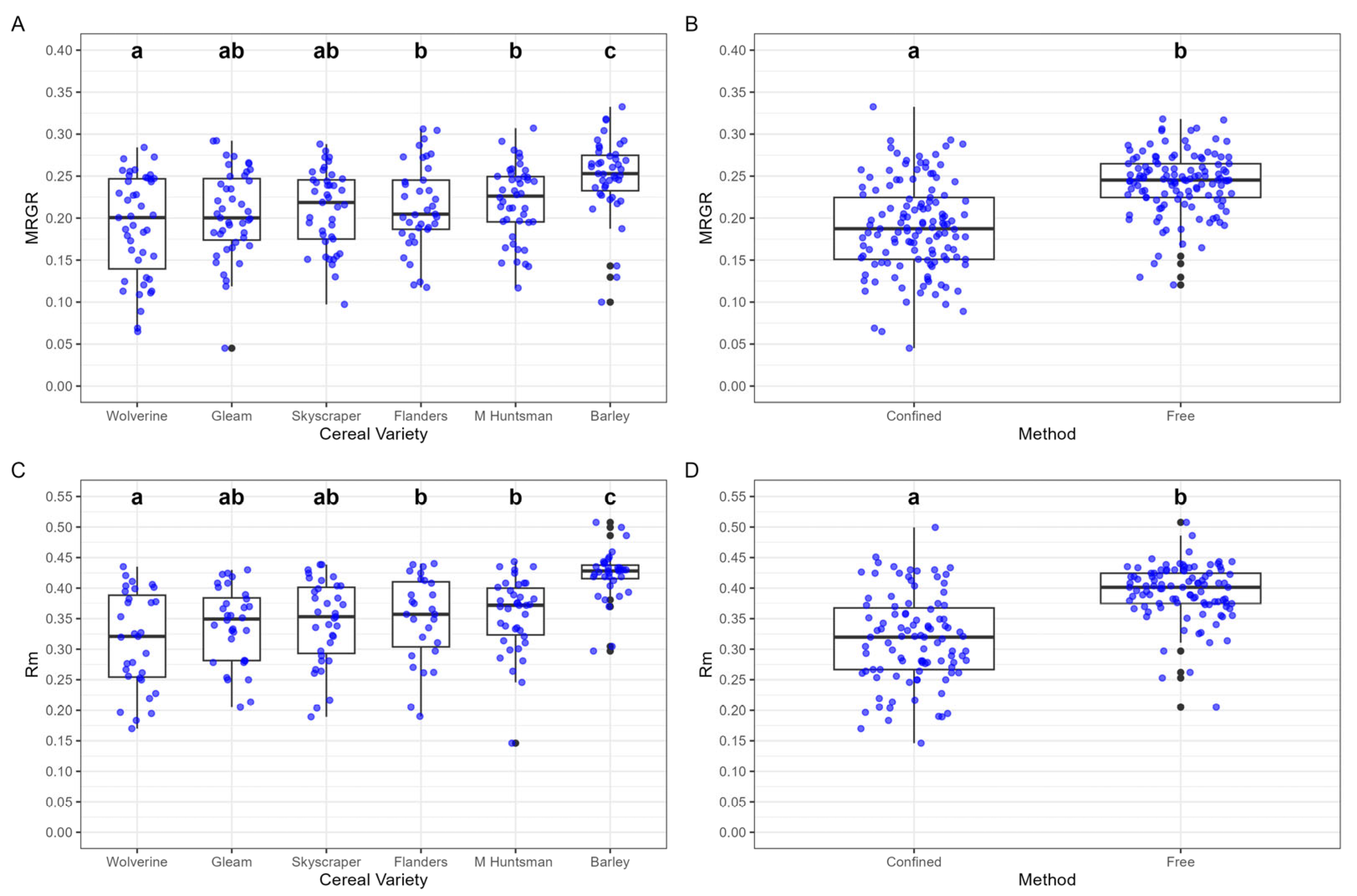

A significant effect of cereal variety was found on bird cherry-oat aphid MRGR, but no significant interaction with confinement method was identified. The highest MRGR was recorded for aphids feeding on barley (0.250 ± 0.007), while the lowest was on Wolverine (0.191 ± 0.009) (

Figure 3A). Wolverine-fed aphids exhibited significantly lower MRGR than those on the older wheat varieties Flanders (0.214 ± 0.008) and Maris Huntsman (0.219 ± 0.007) (

Figure 3A). Confinement significantly reduced MRGR, with confined aphids exhibiting a lower growth rate (0.189 ± 0.005) compared to free aphids (0.242 ± 0.003, n = 122), indicating that the restriction negatively impacted aphid growth (

Figure 3B).

3.2.2. Intrinsic Rate of Increase (rm)

There were significant differences in bird cherry-oat aphid

rₘ across cereal varieties and confinement methods. Among varieties, aphids feeding on barley exhibited the highest

rₘ (0.422 ± 0.007), while those on Wolverine had the lowest (0.315 ± 0.014) (

Figure 3C). Confinement had a significant negative effect on rₘ, with confined aphids having a lower intrinsic rate of increase (0.317 ± 0.007) compared to free aphids (0.394 ± 0.005), demonstrating a strong negative impact of restricted movement on aphid reproductive potential (

Figure 3D).

4. Discussion

Results from this study show that use of clip cages decreased bird cherry-oat aphid performance in terms of both MRGR and

rm, regardless of host plant or variety. As this aphid species typically feeds at the base of the plant stem [

31], confinement to a leaf section is likely to compromise nutrient availability for this species. Similar findings have been reported in other aphid species, where confinement to non-preferred feeding sites alters growth and reproduction [

32]. Other factors involving the microclimate formed in a confined space, such as increased humidity, may also play a role in aphid life-history traits [

32,

33]. In contrast, the use of confinement increased the performance of English grain aphid. An earlier study investigating the potential of a modified lightweight clip cage reported that the performance of this species was similar when confined to this clip cage or left free on the plant [

34]. While it is not possible to directly compare between the two studies, the contrasting confinement methods used further supports the conclusion that experimental method influences aphid performance recorded. However, the fact that these studies indicate a similar or increase in aphid performance when confined is likely to be in part at least due to the fact that this species typically feeds on leaves and so the position of the confinement apparatus would have had a reduced effect on feeding behaviour.

Several studies have investigated resistance to both English grain aphid and bird cherry-oat aphid in wheat lines [e.g. 7,34,35]. However, none of these studies have considered the impact that confinement may have on aphid performance of both aphid species. This is likely to be most important where wheat collections, such as the Watkins and Gediflux collections, are screened [

35] and presence of partial plant resistance is masked by the impact of the experimental technique. Missing the presence of partial plant resistance will have the impact of delaying and possibly preventing useful traits from being introgressed into elite breeding lines. The impact on aphid performance across cereal varieties highlights the role of plant genotype in shaping aphid population dynamics. Resistance mechanisms may include antixenosis, where aphids avoid specific varieties, and antibiosis, where host plant properties negatively impact aphid development and reproduction [

36]. Previous work has reported significant variation in aphid performance when feeding on different lines within wheat collections [

35]. The fact that here we report reduced aphid performance on commercial varieties, such as Wolverine, suggests that selective breeding, such as the inclusion of the Bdv2 gene to confer resistance to BYDV-PAV, may have unintentionally introduced traits that confer partial resistance to these pests [

35]. This is important because recent work has shown that mixtures of wheat varieties have the potential to reduce the performance of English grain aphid [

37]. However, the combination of varieties appears to be important in achieving this effect, therefore, an understanding of aphid performance on and behavioural response to each wheat variety included in a mixture are likely to be important factors in determining the success of this approach. Further considerations could include the use of wheat varieties known to reduce the transmission of BYDV by aphids [

26,

38]. Indeed, on this final point, it is interesting to note that the lowest performance of both species of aphid in this study was recorded when aphids were feeding on the BYDV resistant variety Wolverine.

The higher performance of both aphid species on barley is consistent with findings from previous studies, where host plant suitability was linked to aphid fecundity and growth rates [

18,

39]. This may be attributed to nutritional factors, such as variations in plant secondary metabolites and amino acid profiles, which have been shown to influence aphid development [

40]. The suitability of barley to both aphid species is likely to also reflect the rearing history of aphid populations on this host and is likely due to maternal effects. Maternal effects represent the impact of environmental variation in previous generations on phenotypic variations in the offspring generation. When reproducing parthenogenetically, asexual mother aphids develop telescoping generations (embryos within embryos) so that granddaughters are present inside the bodies of their grandmothers. As a result, aphids have strong maternal and transgenerational effects that can extend for three or more generations [

41,

42].

5. Conclusions

Intrinsic crop resistance is a fundamental basis for functional IPM [

42]. Differences in aphid performance among cereal varieties highlight the potential to identify resistance traits but the experimental methods used to identify such resistance must be given full consideration as these may impact aphid fitness. This knowledge could accelerate resistance breeding programs aimed at developing aphid-resistant lines by enabling the development of molecular markers for aphid susceptibility, thereby aiding plant breeders in selecting for resistant traits more efficiently and reducing reliance on chemical control. Furthermore, an understanding of how varieties vary in susceptibility to

S. avenae and

R. padi may enable development of varietal mixtures that reduce the performance and spread of aphid vectors of BYDV [

37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.D.A.L., J.M.R., E.T.D. and T.W.P.; methodology, M.E.D.A.L., J.M.R., E.T.D. and T.W.P., data acquisition, M.E.D.A.L., data analysis, M.E.D.A.L. and J.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.D.A.L., writing—review and editing, J.M.R., E.T.D. and T.W.P.; supervision, J.M.R., ET.D. and T.W.P.; project administration, T.W.P.; funding acquisition, T.W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AHDB, grant number 21120186.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dedryver, C.-A., Le Ralec, A. and Fabre, F. The conflicting relationships between aphids and men: a review of aphid damage and control strategies. C. R. - Biol. 2010, 333, 539–553.

- Nancarrow, N., Aftab, M., Hollaway, G., Rodoni, B. and Trębicki, P. Yield losses caused by barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV infection in wheat and barley: A three-year field study in South-Eastern Australia. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 645.

- McNamara, L., Lacey, S., Kildea, S., Schughart, M., Walsh, L., Doyle, D. and Gaffney, M.T. Barley yellow dwarf virus in winter barley: Control in light of resistance issues and loss of neonicotinoid insecticides. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021, 186, 132-142.

- Foster, S.P., Paul, V.L., Slater, R., Warren, A., Denholm, I., Field, L.M. and Williamson, M.S. A mutation (L1014F) in the voltage-gated sodium channel of the grain aphid, Sitobion avenae, is associated with resistance to pyrethroid insecticides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 1249–1253.

- Walsh, L., Ferrari, E., Foster, S. and Gaffney, M.T. Evidence of pyrethroid tolerance in the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi in Ireland. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2020, 31, 5-9.

- Shah, F., Coulter, J.A., Ye, C. and Wu, W. Yield penalty due to delayed sowing of winter wheat and the mitigatory role of increased seeding rate. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 119, 126120.

- Greenslade, A.F.C., Ward, J.L., Martin, J.L., Corol, D.I., Clark, S.J., Smart, L.E. and Aradottir, G.I. Triticum monococcum lines with distinct metabolic phenotypes and phloem-based partial resistance to the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2016, 168, 435–449.

- Reynolds, M.P. and Borlaug, N.E. Impacts of breeding on international collaborative wheat improvement. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 3–17.

- Awmack, C.S. and Leather, S.R. Host plant quality and fecundity in herbivorous insects. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 2002, 47, 817–844.

- Wojciechowicz-Zytko, E. and van Emden, H.F. Are aphid mean relative growth rate and intrinsic rate of increase likely to show a correlation in plant resistance studies? J. Appl. Entomol. 1995, 119, 405–409.

- Khan, M. and Port, G. Performance of clones and morphs of two cereal aphids on wheat plants with high and low nitrogen content. Entomol. Sci. 2008, 11, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, I. and Ninkovic, V. Aphid performance and population development on their host plants is affected by weed-crop interactions, J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50 1281–1288.

- Moreno-Delafuente, A. Viñuela, E., Fereres, A., Medina, P. and Trębicki, P. Simultaneous increase in co2 and temperature alters wheat growth and aphid performance differently depending on virus infection. Insects, 2020, 11, 459.

- Birch, L. The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J. Anim. Ecol. 1948, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, L.M. and Quisenberry, S.S. Categorization of six wheat plant introduction lines for resistance to the Russian wheat aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae), J. Econ. Entomol. 1997, 90, 1408–1413.

- Fiebig, M. , Poehling, H.M. and Borgemeister, C. Barley yellow dwarf virus, wheat, and Sitobion avenae: A case of trilateral interactions’, Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2004, 110, 11–21.

- Leather, S.R. and Dixon, A.F.G. Aphid growth and reproductive rates. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1984, 35, 137-140.

- Klueken, A.M. , Poehling, H.-M. and Hau, B. Attractiveness and host suitability of winter wheat cultivars for cereal aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae)’, J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2008, 115, 114–121.

- Sotherton, N.W. and Emden, H.F.V. Laboratory assessments of resistance to the aphids Sitobion avenae and Metopolophium dirhodum in three Triticum species and two modern wheat cultivars. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1982, 101, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Chavez, L.M. , Roberts, J.M., Karley, A.J., Shaw, B. and Pope, T.W. The clip cage conundrum: Assessing the interplay of confinement method and aphid genotype in fitness studies. Insect Sci. 2024, 31, 1591-1602.

- Nalam, V.J., Han, J., Pitt, W.J., Acharya, S.R., Nachappa, P. Location, location, location: Feeding site affects aphid performance by altering access and quality of nutrients. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0245380.

- Crafts-Brandner, S.J. and Chu, C.C. Insect clip cages rapidly alter photosynthetic traits of leaves. Crop Sci. 1999, 39, 1896–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, J., Lozano, E.R. and Poppy, G.M. A simple, light clip-cage for experiments with aphids. Agric. For. Entomol. 2018, 20, 589–592.

- Zadoks, J.C. , Chang, T.T. and Konzak, C.F. A decimal code for the growth stages of cereals. Weed Res. 1974, 14, 415–421.

- Hu, X.S. Zhang, Z. F., Zhu, T.Y., Song, Y., Wu, L.J., Liu, X.F., Zhao, H.Y. and Liu, T.X. Maternal effects of the English grain aphids feeding on the wheat varieties with different resistance traits. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7344. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Martïnez, E.S. Bosque-Pérez, N.A., Berger, P.H. and Zemetra, R.S. Life history of the bird cherry-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi (Homoptera: Aphididae), on transgenic and untransformed wheat challenged with barley yellow dwarf virus. J. Econ. Entomol. 2004, 97, 203–212.

- Thieme, T. and Heimbach, U. Development and reproductive potential of cereal aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) on winter wheat cultivars. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 1996, 19, 1-18.

- Wyatt, I.J. and White, P.F. Simple estimation of intrinsic increase rates for aphids and tetranychid mites. J. Appl. Ecol. 1977, 14, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D. , Mächler, M., Bolker, B., and Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48.

- Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.10.7-100002. Available online: https://rvlenth.github.io/emmeans/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Leather, S.R. and Dixon, A.F.G. (1981) The effect of cereal growth stage and feeding site on the reproductive activity of the bird-cherry aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi. Ann. App. Biol. 1981, 97, 135–141.

- Yin, W. Xue, Q., Su, L., Feng, X., Feng, X., Zheng, Y. and Hoffmann, A. Microhabitat separation between the pest aphids Rhopalosiphum padi and Sitobion avenae: food resource or microclimate selection? J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94 795–804.

- Ma, G. Behavioural thermoregulation alters microhabitat utilization and demographic rates in ectothermic invertebrates. Anim. Behav. 2018, 142, 49–57.

- Kou, X. , Bai, S., Luo, Y., Yu, J., Guo, H., Wang, C., Zhang, H., Chen, C., Liu, X. and Ji, W. Construction of a modified clip cage and its effects on the life-history parameters of Sitobion avenae (Fabricius) and defense responses of Triticum aestivum. Insects. 2022, 13, 777.

- Aradottir, G.I., Martin, J.L., Clark, S.J., Pickett, J.A. and Smart, L.E. Searching for wheat resistance to aphids and wheat bulb fly in the historical Watkins and Gediflux wheat collections. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2017, 170, 179-188.

- Stout, M.J. Reevaluating the conceptual framework for applied research on host-plant resistance. Insect Sci. 2013, 20, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tous-Fandos, A., Gallinger, J., Enting, A., Chamorro-Lorenzo, L., Sans, F.X. and Ninkovic, V. Effect of plant identity in wheat mixtures on English grain aphid (Sitobion avenae) control. J. Appl. Entomol. 2025, 149, 132-140.

- Tanguy, S. and Dedryver, C.-A. Reduced BYDV-PAV transmission by the grain aphid in a Triticum monoccum line. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 123, 281-289.

-

Migui, S.M. and Lamb, S.J. Patterns of resistance to three cereal aphids among wheats in the genus Triticum (Poaceae). Bull. Ent. Res. 2003, 93, 323 – 333.

- Eleftherianos, I., Vamvatsikos, P., Ward, D. and Gravanis, F. (2006) Changes in the levels of plant total phenols and free amino acids induced by two cereal aphids and effects on aphid fecundity. J. Appl. Entomol. 2006, 130, 15-19.

- Dingle, H. Maternal effects in insect life histories. Annu. Rev. Entomol, 1991, 36, 1–34.

- Hales, D.F. , Wilson, A.C.C., Sloane, M.A., Simon, J.-S., le Gallic, J.-F., Sunnucks, P. Lack of detectable genetic recombination on the X chromosome during the parthenogenetic production of female and male aphids. Genet. Res. 2002, 79, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, K.K., Stenberg, J.A. and Lankinen, A. Making sense of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in the light of evolution. Evol. Appl. 2020, 13, 1791–1805.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).