Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

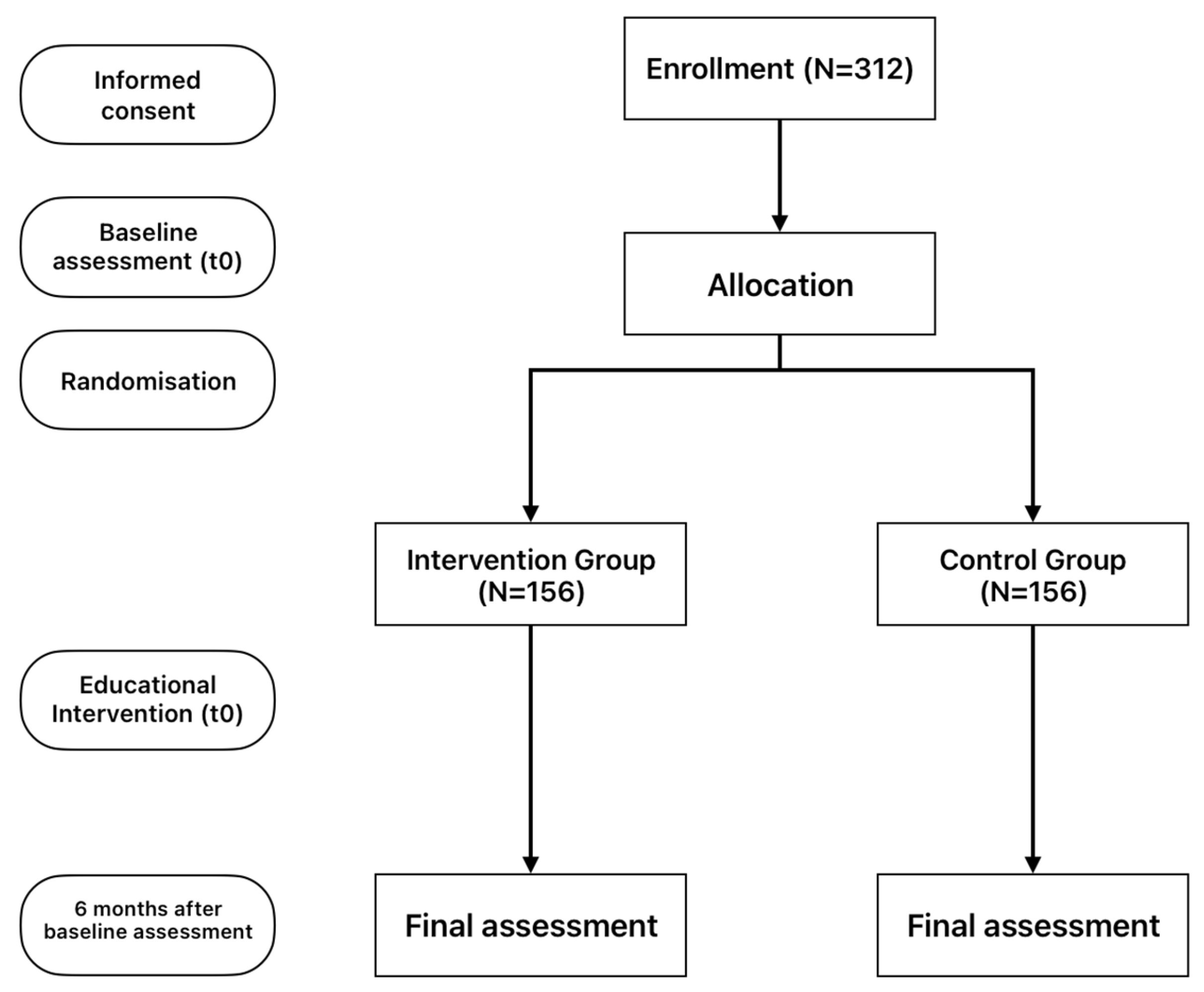

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Description of this study’s Intervention

2.3. Data Collection and Instruments

2.3.1. European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire 16 (HLS-EU-16)

2.3.2. The Patient Activation Measure - 13 (PAM-13)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006, 90, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, R.N.; Aung, T.; Medeiros, F.A. The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Glaucoma: A Review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1901–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W.; Wolf, M.S.; Feinglass, J.; Thompson, J.A.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Huang, J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, K.W.; Lee, P.P. Health literacy and ophthalmic patient education. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2010, 55, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.S.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Baker, D.W. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.K.; Homme, R.P.; Stanisic, D.; Tyagi, S.C.; Singh, M. Protecting the aging eye with hydrogen sulfide. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 99, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.C.; McClure, C.A.; Ramos, S.E.; Schlundt, D.G.; Pichert, J.W. Compliance barriers in glaucoma: A systematic classification. J. Glaucoma 2003, 12, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.C.; Cheng, C.Y. Associations between chronic systemic diseases and primary open angle glaucoma: An epidemiological perspective. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2017, 45, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DS, F. Doctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma. Results from the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, N.; You, W. Design and fault diagnosis of DCS sintering furnace's temperature control system for edge computing. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, M.D.; Aiken, L.H.; Kurtzman, E.T.; Olds, D.M.; Hirschman, K.B. The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011, 30, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.R.; Stockard, J.; Tusler, M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv. Res. 2005, 40, 1918–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleath, B.; Carpenter, D.M.; Blalock, S.J.; Sayner, R.; Muir, K.W.; Slota, C.; Giangiacomo, A.L.; Hartnett, M.E.; Tudor, G.; Robin, A.L. Applying the resources and supports in self-management framework to examine ophthalmologist-patient communication and glaucoma medication adherence. Health Educ. Res. 2015, 30, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geitona, M.; Latsou, D.; Toska, A.; Saridi, M. Polypharmacy and Adherence Among Diabetic Patients in Greece. Consult. Pharm. 2018, 33, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliarou, M.; Bakola, E.; Nikolentzos, A.; Sarafis, P. Reliability and validity of the Greek translation of the patient assessment of chronic illness care + (PACIC-PLUS GR) survey. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilleos, M.; Merkouris, A.; Charalambous, A.; Papastavrou, E. Medication adherence, self-efficacy and health literacy among patients with glaucoma: A mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e039788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, P.J.; Buhrmann, R.; Quigley, H.A.; Johnson, G.J. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2002, 86, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.N.; Bowd, C.; Medeiros, F.A.; Weinreb, R.N.; Sample, P.A.; Hoffmann, E.M.; Zangwill, L.M. Combining structural and functional testing for detection of glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The Health Belief Model as an Explanatory Framework in Communication Research: Exploring Parallel, Serial, and Moderated Mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finset, A. Patients’ values and preferences and communication about life expectancy: Combining honesty and hope. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efthymiou, A.; Middleton, N.; Charalambous, A.; Papastavrou, E. The Association of Health Literacy and Electronic Health Literacy With Self-Efficacy, Coping, and Caregiving Perceptions Among Carers of People With Dementia: Research Protocol for a Descriptive Correlational Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pelikan, J.M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsichla, L.; Patelarou, E.; Detorakis, E.; Tsilimparis, M.; Skatharoudi, C.; Kalaitzaki, M.; Garedaki, Ε.; Giakoumidakis, K. Translation and Validation of the Greek Version of the Patient Activation Measure-13 in Glaucoma Patients. Hell. J. Nurs. 2024, 63, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Moljord, I.E.; Lara-Cabrera, M.L.; Perestelo-Perez, L.; Rivero-Santana, A.; Eriksen, L.; Linaker, O.M. Psychometric properties of the Patient Activation Measure-13 among out-patients waiting for mental health treatment: A validation study in Norway. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insignia Health, L. Patient Activation Measure (PAM) 13 License Materials. 2011.

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public. Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Lorig, K.; Holman, H.; Grumbach, K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jama 2002, 288, 2469–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, A.; Cronin, C.; Cook, G.; Whitehead, A. Developing Coaches’ Knowledge of the Athlete–Coach Relationship Through Formal Coach Education: The Perceptions of Football Association Coach Developers. Int. Sport. Coach. J. 2023, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, C.Y.; Cavanaugh, K.; Wallston, K.A.; Rothman, R.L. Self-efficacy links health literacy and numeracy to glycemic control. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15 Suppl. 2, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xia, H.; Zhang, X.; Fontes-Garfias, C.R.; Swanson, K.A.; Cai, H.; Sarkar, R.; Chen, W.; Cutler, M.; et al. Neutralizing Activity of BNT162b2-Elicited Serum. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1466–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.C. A comprehensive perspective on patient adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, S30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briesen, S.; Geneau, R.; Roberts, H.; Opiyo, J.; Courtright, P. Understanding why patients with cataract refuse free surgery: The influence of rumours in Kenya. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2010, 15, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; European, C.H.L.P. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide, I.; Uiters, E.; Sørensen, K.; Röthlin, F.; Pelikan, J.; Rademakers, J.; Boshuizen, H.; consortium, E. Health literacy in Europe: The development and validation of health literacy prediction models. Eur. J. Public. Health 2016, 26, 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Thombs, B.D.; Schmid, M.R. The Swiss Health Literacy Survey: Development and psychometric properties of a multidimensional instrument to assess competencies for health. Health Expect. 2014, 17, 396–417. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.A.; O’Donoghue, A.C.; Sullivan, H.W.; Willoughby, J.F.; Squire, C.; Parvanta, S.; Betts, K.R. Communicating efficacy information based on composite scores in direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 583–590. [Google Scholar]

- Pelikan, J.M.; Ganahl, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Sørensen, K. Measuring health literacy in Europe: Introducing the European health literacy survey questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). In International handbook of health literacy; Policy Press: 2019; pp. 115–138.

- Nutbeam, D.; Muscat, D.M. Health promotion glossary 2021. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 1578–1598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bonetti, L.; Tolotti, A.; Anderson, G.; Nania, T.; Vignaduzzo, C.; Sari, D.; Barello, S. Nursing interventions to promote patient engagement in cancer care: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 133, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryvicker, M.; Feldman, P.H.; Chiu, Y.L.; Gerber, L.M. The role of patient activation in improving blood pressure outcomes in Black patients receiving home care. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2013, 70, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, A.L.; Novack, G.D.; Covert, D.W.; Crockett, R.S.; Marcic, T.S. Adherence in glaucoma: Objective measurements of once-daily and adjunctive medication use. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprioli, J.; Coleman, A.L. Intraocular pressure fluctuation a risk factor for visual field progression at low intraocular pressures in the advanced glaucoma intervention study. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1123–1129.e1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrani, S.; Zeimer, R.; Wilensky, J.; Gieser, D.; Vitale, S.; Lindenmuth, K. Large diurnal fluctuations in intraocular pressure are an independent risk factor in patients with glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2000, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman-Casey, P.A.; Blachley, T.; Lee, P.P.; Heisler, M.; Farris, K.B.; Stein, J.D. Patterns of Glaucoma Medication Adherence over Four Years of Follow-Up. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 2010–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uji, A.; Yoshimura, N. Application of extended field imaging to optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1272–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Intervention-parts | Short Description | Methods/Tools | Expected Outcomes |

| Training Session | A 15-minute session conducted by the first researcher, covering the disease, its treatment, and long-term management. | Researcher-led informational presentation, and active participant discussion. | Enhanced patient understanding of the disease and treatment options. |

| Online Videos | Appropriately selected YouTube videos focusing on disease education, treatment, and self-management techniques (with Greek Subtitles). | Videos from the World Glaucoma Association, including: "Understanding Glaucoma; World Glaucoma Week 2022; & "Patient Education Movie - World Glaucoma Week 2021" | Increased patient understanding of disease management through visual content. |

| Printed Material (Brochure) | Provision of a brochure containing essential information about glaucoma, treatment options, and self-management tips. | Printed brochure with text and graphics for patient education. | Improved patient knowledge regarding glaucoma and self-management strategies. |

| GROUP | |||||||

| Control | Intervention | Total | |||||

| Count | N % | Count | N % | Count | N % | ||

| Biological sex | Female | 63 | 40.1% | 71 | 45.8% | 134 | 42.9% |

| Male | 94 | 59.9% | 84 | 54.2% | 178 | 57.1% | |

| Education level | Primary | 113 | 72.0% | 115 | 74.2% | 228 | 73.1% |

| Secondary | 20 | 12.7% | 24 | 15.5% | 44 | 14.1% | |

| Tertiary | 24 | 15.3% | 16 | 10.3% | 40 | 12.8% | |

| Comorbidity | No | 13 | 8.3% | 12 | 7.7% | 25 | 8.0% |

| Yes | 144 | 91.7% | 143 | 92.3% | 287 | 92.0% | |

| Group | p-value | ||

| Control | Intervention | ||

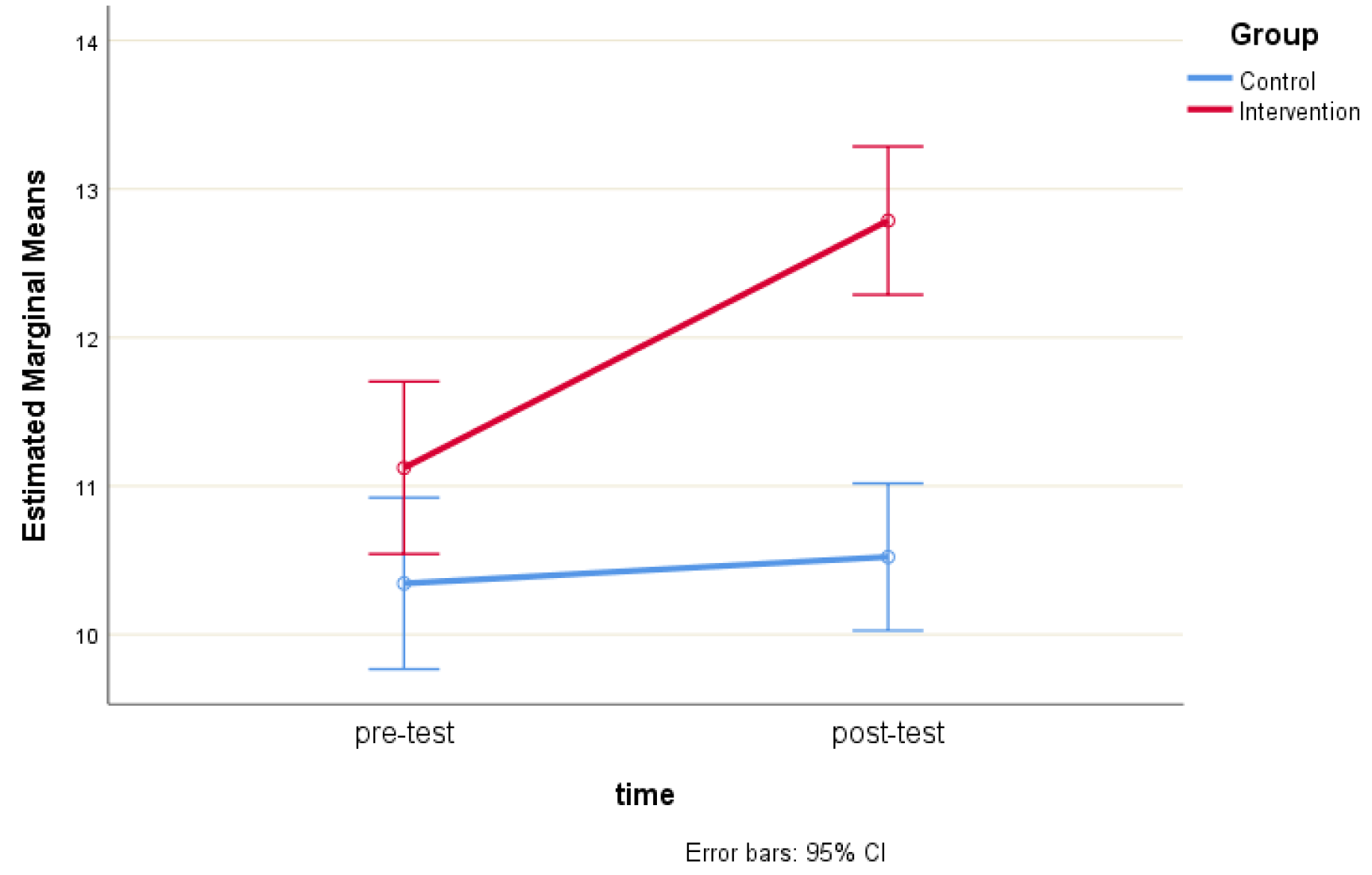

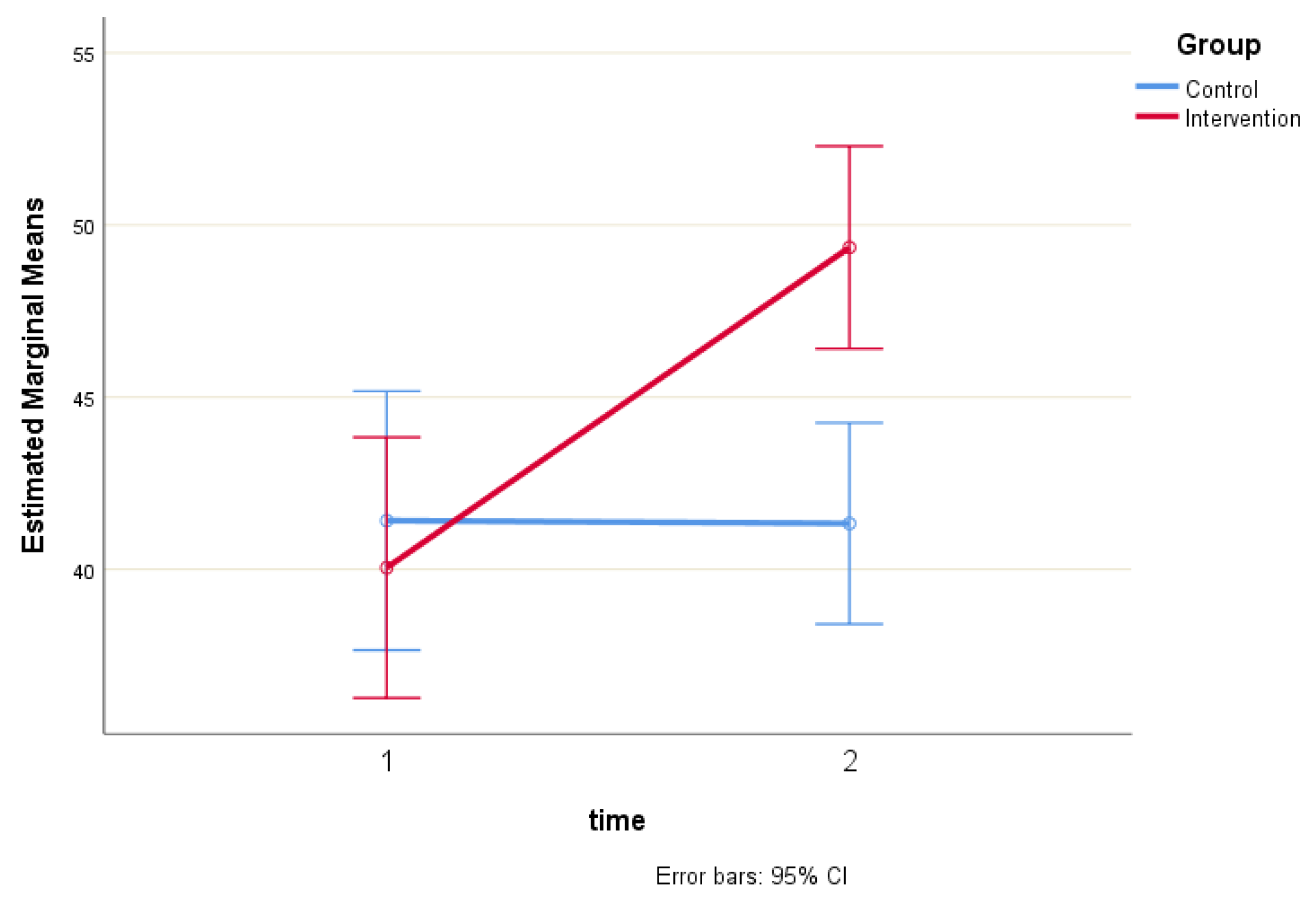

| PAM-13 score (pre) | 41.4 ± 24.2 | 40.1 ± 23.7 | p < 0.001 |

| PAM-13 score (post) | 41.3 ± 24.1 | 49.3 ± 10. 4 | |

| HLS-EU16 score (pre) | 10.3 ± 3.8 | 11.1 ± 3.5 | p < 0.001 |

| HLS-EU16 score (post) | 10.5 ± 3.6 | 12.8 ± 2.6 | |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95,0% Confidence Interval for B | Collinearity Statistics | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant) | -2.113 | 8.847 | -.239 | .811 | -19.521 | 15.296 | |||

| HLS-EU16 score (pre) | 3.307 | .318 | .510 | 10.391 | .000 | 2.681 | 3.933 | .974 | 1.026 |

| Group | -3.772 | 2.337 | -.079 | -1.614 | .108 | -8.370 | .826 | .981 | 1.019 |

| Biological sex | -.900 | 2.351 | -.019 | -.383 | .702 | -5.526 | 3.726 | .989 | 1.011 |

| Age | .104 | .090 | .062 | 1.156 | .249 | -.073 | .281 | .804 | 1.243 |

| Education level | 3.863 | 1.844 | .114 | 2.095 | .037 | .235 | 7.492 | .794 | 1.259 |

| Comorbidity | -2.495 | 4.271 | -.028 | -.584 | .560 | -10.900 | 5.910 | .996 | 1.004 |

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | Collinearity Statistics | ||||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| (Constant) | 11.868 | 8.453 | 1.404 | 0.161 | -4.765 | 28.501 | ||||

| HLS-EU16 score (post) | 1.261 | 0.330 | 0.222 | 3.818 | 0.000 | 0.611 | 1.912 | 0.870 | 1.150 | |

| Group | 5.356 | 2.198 | 0.141 | 2.437 | 0.015 | 1.031 | 9.682 | 0.879 | 1.137 | |

| Biological sex | 1.187 | 2.100 | 0.031 | .565 | 0.572 | -2.946 | 5.320 | 0.983 | 1.018 | |

| Age | 0.093 | .080 | 0.070 | 1.165 | 0.245 | -.064 | .250 | 0.810 | 1.235 | |

| Education level | 2.736 | 1.636 | 0.102 | 1.673 | 0.095 | -.482 | 5.955 | 0.801 | 1.249 | |

| Comorbidity | 0.312 | 3.811 | 0.004 | .082 | 0.935 | -7.187 | 7.810 | 0.992 | 1.008 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).