1. Introduction

Glaucoma, one of the most important chronic diseases, is a major public health problem because of its serious impact on the vision and quality of life of patients [

1]. It is characterized by progressive loss of vision and increased intraocular pressure, making early diagnosis and proper management essential. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology (2021), early and effective self-management of the disease outside hospitals can slow the progression of the disease and reduce its negative impact on patients’ daily lives. This includes adherence to medication, early recognition of symptoms, regular visits to the ophthalmologist, and proper use of eye drops [

2]. However, many patients find it difficult to adequately manage their condition due to several factors, including health literacy and patient activation [

3].

Health literacy plays a key role in managing chronic diseases[

4]. Moreover, comprehensive daily disease management requires patients to be able to find, understand, and use relevant health information [

5]. The literature highlights that health literacy is not only a matter of individual skills. Still, it is also highly dependent on the accessibility of health systems, the communication skills of health professionals, and the level of complexity of health information [

4]. Patients with a high level of health literacy are better able to understand healthcare professionals’ instructions, read and understand drug labels, follow treatment plans correctly, and make informed health decisions, whereas patients with a low level of health literacy have difficulties in understanding healthcare professionals instructions, make mistakes in taking medications, and face worse health outcomes, such as increased hospitalization rates and increased mortality [

6].

The level of patient activation is an equally important factor in the management of chronic conditions. According to Hibbard et al. (2005), patient activation refers to the extent to which patients have the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage their health [

1]. More specifically, patients with higher activation levels are more likely to adhere to treatment instructions, adopt healthy behaviors, and avoid unnecessary hospitalization [

7]. On the other hand, patients with lower levels of activation tend to be more passive and have greater difficulty in self-managing their health. Therefore, interventions designed to enhance patient activation involve educating, providing clear and accessible information, empowering patients with support, and equipping them with self-management tools[

8].

In Greece, the levels of health literacy and patient activation remain low [

9], which makes it difficult to manage chronic diseases, such as glaucoma [

10]. According to a recent study, the lack of appropriate education and support programs for patients with chronic diseases has led to increased rates of noncompliance with treatment guidelines and worsening health outcomes [

11].

This study aimed to assess the health literacy and self-management activation levels of glaucoma patients in outpatient clinics, as well as to explore the relationship between these factors. Despite extensive research, there is still a significant gap in the literature on the interaction between health literacy and patients’ level of activation in glaucoma management[

12]This study intends to contribute new insights to the existing body of knowledge.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study Design and Variables

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 312 patients with glaucoma from an outpatient clinic of a University Hospital, in Heraklion, Crete, Greece. In the present study, the dependent variables were the level of health literacy and the level of activity of glaucoma patients, and the independent variables were biological sex, age, educational level, and comorbidity. The population of the present study consisted of patients diagnosed with glaucoma. The diagnosis of glaucoma was based on already published diagnostic criteria: a) high intraocular pressure, b) optic-nerve atrophy, and c) deficits in the visual fields [

13]. The diagnosis of glaucoma was confirmed based on published criteria, indicating that the disease is not in an early stage, as evidenced by extensive visual field defects ( MD > -8,5 dB) [

14].

2.2. Participants and Sample

The sample was obtained through convenience sampling of glaucoma patients who attended the outpatient clinic of the Ophthalmology Department of the University Hospital of Heraklion (Crete, Greece) between November 2023 and May 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) age ≥ 18 years, ii) informed written consent to participate in the study, iii) adequate knowledge of the Greek language (writing and reading), and iv) diagnosis of the condition. Patients with incomplete information in their health records or those who provided incomplete information were excluded.

2.3. Data Collection and Instruments

Data were collected using three questionnaires: a self-report questionnaire for demographic characteristics (biological sex, age, educational level, and comorbidities) specifically designed for this study, the Greek version of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire 16, and the Greek version of the Patient Activation Measure 13. It should be noted that written permission was obtained to use each questionnaire from each developer.

2.3.1. European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire 16 (HLS-EU-16)

The European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire 16 (HLS-EU-16) [

15] was used to assess participants’ health literacy with written permission obtained from its creators. Additionally, this tool has been translated into the Greek language and validated within the Greek population [

16]. This questionnaire is available in three versions, depending on the number of questions (47, 16, or 6). The version used for this study was developed based on the Rasch model [

15]. It includes 16 questions, each of which is answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very easy”) to 4 (“very difficult”). Answers “very easy” and “easy” receive a point, while answers “very difficult” and “difficult” do not receive a point [

15]. To calculate the total score of the questionnaire, the score for each answer is added, with the final score having a range of 0-16 [

15]. Participants are then categorized based on their scores, specifically, scores between 0-8 indicate inadequate health literacy, 9-12 suggest problematic health literacy, and 13-16 indicate sufficient health literacy [

15].

2.3.2. The Patient Activation Measure - 13 (PAM-13)

The Patient Activation Measure-13 (PAM-13) questionnaire was used to assess the patient’s activity level [

18]. Additionally, this tool has been translated into the Greek language and validated within the Greek population [

18]. It was created by Hibbard JH [

19], a short version of the original questionnaire with 22 questions[

1]. The PAM-13 includes 13 questions, each of which is answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”), with the additional option “not applicable”. To calculate the total score of the questionnaire, the score of each answer is summed and the sum is divided by the number of answers given by the study participant, excluding the “not applicable” answers [

18]. This calculation results in a raw score, ranging from 13 to 52. This raw score is then algebraically transformed to a standardized score between 0 and 100. Higher PAM score values are indicative of higher patient activity levels [

20,

21]. Furthermore, patients based on their scores are classified into four levels of activity: a) Level 1 with a score of ≤ 47.0 (“disengaged &overwhelmed”), b) Level 2 with a score of 47.1-55.1 (becoming aware but still struggling), c) Level 3 with a score of 55.2-67.0 (taking action & gaining control), and d) Level 4 with a score ≥ 67.1 (maintaining behavior & pushing further). Moreover, it has been used primarily in patients with chronic diseases but also at the level of primary health care. More specifically, it has been evaluated in a series of patients with chronic diseases, elderly patients with comorbidities, surgical health problems, and patients suffering from neurological diseases, diabetes mellitus, and osteoarthritis [

20].

2.4. Statistical analysis

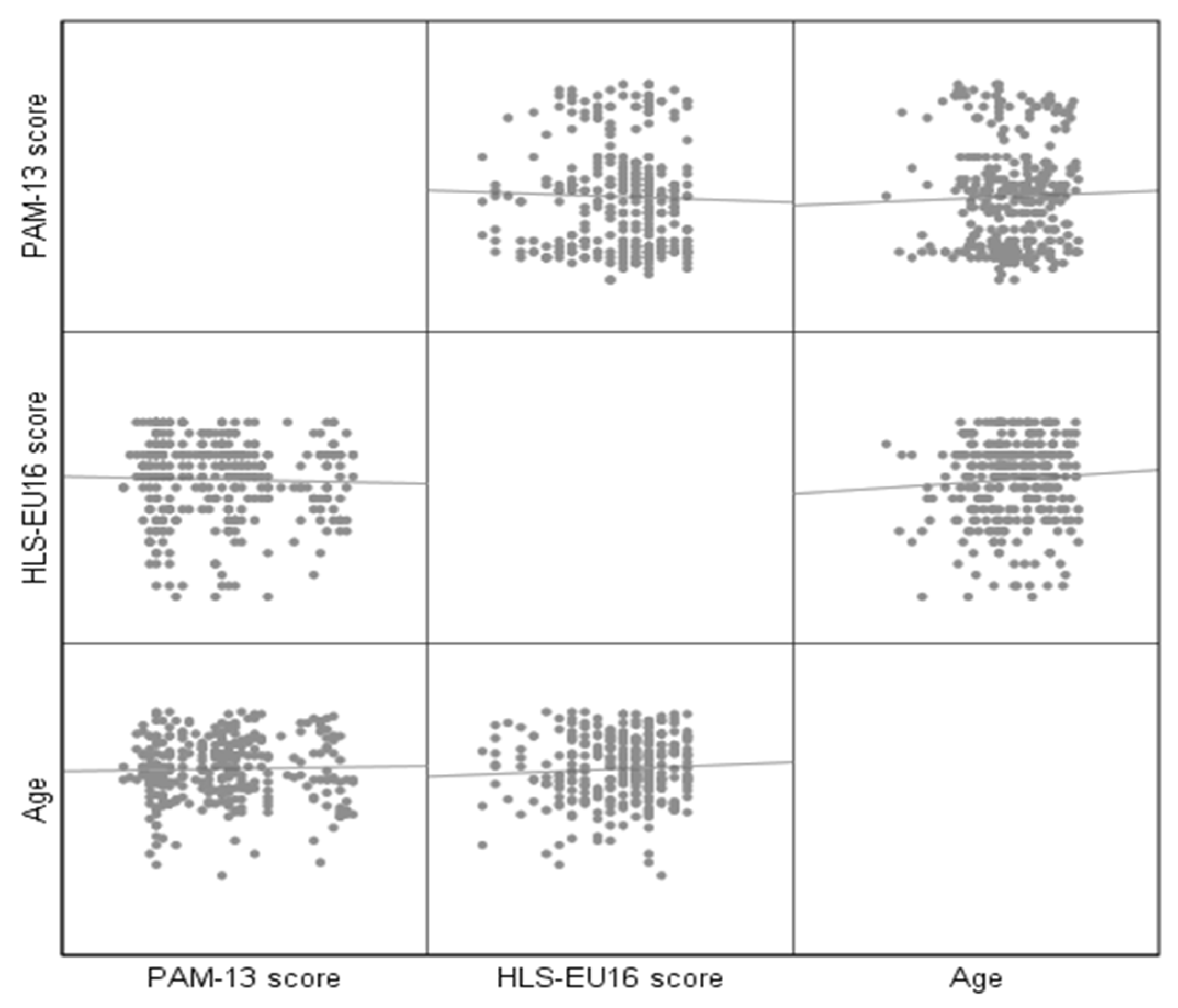

We performed the statistical analysis using ΙΒΜSPSS version 26.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were expressed by frequency and percentage. Internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s α coefficient >0.7 indicates acceptable reliability, and that the items are interdependent and homogeneous in terms of the construct they measure. To test the condition of normality, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used as well as the “Normal Q-Q plot”, “Detrended Normal Q-Q plot”, and “Box Plot” graphs. To correlate two continuous variables, we used the Pearson coefficient (r). Spearman’s correlation index (ρ) was used to investigate the relationship between a continuous and an ordinal variable. To investigate the relationship between a continuous and a dichotomous variable, we used the Point-Biserial coefficient (pbs). Moreover, a matrix of scatter plots matrix was created to illustrate the bivariate relationships among various combinations of variables. Each scatter plot within the matrix depicts the correlation between a specific pair of variables, thereby facilitating the examination of multiple relationships within a single visual representation. For all tests, statistical differences were determined to be significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

The study sample consisted of 312 patients, 134 women (42.9%) and 178 men (57.1%), mean age of 63.9±14.4 years. The 228 patients (73.1%) had primary, 44 (14.1%) secondary, and 40 (12.8%) tertiary educational levels. Two hundred eighty-seven patients (92 %) had concomitant disease (

Table 1). Cronbach’s alphas for HLS-EU16 and PAM-13 were 0.88 and 0.95, respectively.

Regarding the activity level of the patients, the mean value of the PAM-13 questionnaire was calculated as 40.7 out of 100 (±23.9). As shown in

Table 2, 211 patients (67.6%) were classified as level 1(disengaged & overwhelmed), 29 (9.3%) as level 2 (becoming aware but still struggling), 17 (5.4%) as level 3 (taking action & gaining control), and 55 (17.6%) as level 4 (maintaining behavior & pushing further).

There was no statistically significant correlation between the HLS-EU16 and PAM-13 (r (312) =-0.030, p = 0.602), as depicted in

Table 3. Additionally, there was no statistically significant correlation between PAM-13 and age, r (312) = 0.028, p = 0.617. However, there was a statistically significant, though low, positive correlation between PAM-13 and educational level, ρ(312) = 0.122, p = 0.031. No significant correlation was found between PAM-13 and comorbidity, pbs(312) = -0.039, p = 0.492. Additionally, HLS-EU16 showed no statistically significant correlation with biological sex [pbs(312) = 0.007, p = 0.903] and age [r(312) = 0.060, p = 0.291] (

Table 4).

The participants’ average health literacy level was 10.7 out of 16 (SD: ±3.7). As highlighted in

Table 5, of the participants, 79 (25.3%) had inadequate health literacy, 109 (34.9%) had problematic literacy levels, and 124 (39.7%) demonstrated sufficient literacy.

Figure 1 shows, by pairs, the relationship between the 3 variables: Age, PAM 13, and HLS.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to assess the health literacy and self-management activation levels of glaucoma patients in outpatient clinics and explored the relationship between these two factors. Our findings suggest that most participants had low levels of patient activation and health literacy that ranged from insufficient to problematic. Notably, there was no significant correlation between health literacy and self-management activation. Moreover, no significant associations were found between patient activation and demographic factors such as sex or age, suggesting that these variables do not influence activation levels. However, we did observe a statistically significant, though weak, positive correlation between patient activation (PAM-13) and educational level.

A major finding of the present study was that patients with glaucoma exhibited insufficient and problematic levels of health literacy. Alongside, their activation levels were categorized at the lowest stage, level 1, indicating that they were disengaged and overwhelmed. This suggests that these patients may not adequately understand the information provided to them regarding their condition and its management. Health literacy is a crucial public health goal as it directly affects individuals’ ability to manage their health and make informed decisions [

22]. The lack of this literacy can seriously affect patients’ health, leading to poor adherence to medical instructions, which worsens their health condition [

23].

Another major finding of the present study was that patients’ activation levels were at the lowest level, characterized by disengagement and feeling overwhelmed. This is problematic, since, patients with low activation levels are more likely to feel overwhelmed and less likely to engage actively in their healthcare [

24]. This means that these patients feel powerless in the face of their illness and do not take appropriate initiatives to manage their condition. These findings suggest the need for better education and support for patients with glaucoma to improve their health literacy and activation levels. Increasing patient activation levels can reduce healthcare costs and better health outcomes [

25]. It may be necessary to develop personalized programs that help patients better understand their condition and become more actively involved in managing their health [

19].

As previously mentioned, another key finding of this study was the absence of a significant association between the patient’s health literacy level and their activation level. Some might expect a rational relationship between these two variables, given that improved health literacy typically leads to better knowledge and understanding of the disease. This is a crucial foundation for developing self-management and self-care behaviors, both of which inherently involve the connotation of acting. Conversely and in line with our results, the literature describes studies that do not show a clear relationship or dependence between health literacy and patient activation levels[

26]. It seems that while health literacy is crucial, it does not always translate into higher patient activation. However, studies that have evaluated the association between health literacy and patient activation are limited or contradictory regarding the association between these two factors[

27]. Additionally, a review highlighted that the relationship between health literacy and patient activation is not always straightforward and may be influenced by other factors, such as socioeconomic conditions and support from the healthcare system[

28]. A potential explanation for this could be that other factor, such as cultural differences or the quality of information provided, could have a more important influence on the understanding and use of health information. In addition, patients’ low activation despite adequate health literacy may suggest the need for further education and support to enhance their involvement in disease management. Support programs, expert guidance, and the provision of specific strategies can enhance activation [

29].

The finding that health literacy did not show a statistically significant correlation with education level contrasts with older studies, which often indicate that education enhances an individual’s ability to understand and use health information [

11,

28]. However, more recent studies show that the complexity of health information can be a barrier even for people with higher education, as specialized medical terminology and concepts can be a challenge, regardless of the general level of education [

30]. Additionally, a study has suggested that cultural, linguistic, and contextual factors can significantly impact health literacy [

31]. For instance, individuals with higher education, but who are not proficient in the language of healthcare materials may have lower health literacy [

32]. Moreover, the relationship between educational level and patient activation is consistent with the literature, which suggests that more educated patients are generally more engaged in managing their health. Studies show that patients with higher levels of education are more likely to be active and involved in their healthcare [

24] and that patient activation, influenced by education level, is associated with better health outcomes [

33]. Although knowledge of health information does not always mean that patients apply this knowledge to their daily decisions, due to a gap between understanding health information and being able or willing to take action based on that knowledge [

34], the association mentioned above is reasonable. A higher education level is more likely to be associated with better patient activation, as individuals with more education may be better equipped to engage in self-care and manage their health effectively. Furthermore, patients may have the required knowledge but not the tools or support to translate that knowledge into action.

Patient activation levels and comorbidities were not significantly associated in our study, this could suggest that glaucoma patients, due to the severe comorbidities, often have reduced compliance or interest in managing their glaucoma. This may lead to inertia in terms of monitoring and treating the condition, thereby increasing the risk of ocular health deterioration. In addition, the lack of a significant association between health literacy levels and comorbidities may suggest the need for patients to be better informed due to the complexity of their condition. Moreover, it suggests the need for targeted nursing educational interventions in outpatient clinics for glaucoma patients that consider the presence of comorbidities and the complex nature of health management in these patients. Furthermore, the lack of a statistically significant correlation between health literacy and demographic factors in this study echoes findings from other studies, which also highlight that health literacy alone may not address all barriers to effective patient engagement [

35,

36].

These findings have important implications for patients and healthcare professionals. For example, healthcare professionals could encourage their patients to more actively participate in their healthcare, and seek more information, and education about their condition. Moreover, patients need support to overcome the challenges of treatment adherence and actively participate in making decisions about their health. Nurses could develop approaches that consider cultural differences and the qualitative content of health information. Individualizing educational interventions according to each patient’s needs and level of understanding is also critical. Nurses can play a key role in boosting patients’ confidence and providing tools to improve their treatment adherence. Physicians should enhance communication with their patients to ensure that patients fully understand their condition and treatment options and should closely monitor patient compliance with treatment and adjust treatment plans according to patient’s individual needs. However, healthcare professionals may need additional education and support to empower patients in managing their diseases. Nevertheless, all the above could be made possible through targeted educational interventions and educational programs that take into account the comorbidities and complexities of health management, especially for patients with chronic conditions, such as glaucoma.

Limitations

This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first study that examines the health literacy and patient activation levels and their potential association in patients with glaucoma in Greece. While it contributes to existing literature, there are a few limitations worth mentioning. First, the cross-sectional design of the study did not allow causal conclusions to be drawn. Second, the study focused on a specific geographical and socioeconomic group, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings and conditions. Finally, the assessment of activation and health literacy was based on self-reported data, which may contain biases. The participants may not always respond with complete accuracy or honesty. Future studies could broaden the sample range to include different geographical and socio-economic contexts to increase the generalizability of the results. Conducting longitudinal studies would allow for the examination of causal relationships between health literacy, patient activation, and other factors. The use of objective assessment methods, combined with self-reported data, could reduce the risk of bias and provide more accurate measurements.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of the present study suggest that patients with glaucoma had moderate to low levels of health literacy and patient activation. However, and surprisingly, there was no association between health literacy status and patient activation levels. Additionally, these two parameters did not show significant associations with other variables, except for education level, which exhibited a weak correlation with patients’ activation levels. Healthcare managers and policy makers could utilize our findings and improve the health literacy and patient activation of patients with glaucoma. Moreover, healthcare professionals could improve chronic disease outcomes, such as glaucoma by providing patients with higher quality of information, boosting their confidence, and encouraging them to adhere to their treatment plans, this could improve their satisfaction with care and reduce hospitalizations. Furthermore, nurse-led patient education intervention could be implemented to enhance the patient activation and health literacy of patients with glaucoma in outpatient clinics. Such interventions could promote self-management and self-care behaviors, which are crucial for improved healthcare outcomes.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., and K.G.; methodology, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., and K.G.; software, L.T., E.P., E.D., A.C., EL.D, and K.G.; validation, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., A.C., EL.D, and K.G.; formal analysis, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., and K.G.; investigation, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., A.C., and K.G.; resources, L.T., E.P., E.D., and K.G.; data curation, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.C., EL.D, and K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., A.C., EL.D, and K.G.; writing—review and editing, L.T., E.P., E.D., M.T., A.P., A.C., EL.D, and K.G.; visualization, L.T., E.P., and K.G.; supervision, E.P., and K.G.; project administration, L.T., E.P., E.D., and K.G; . All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the research ethics committees of both the Hellenic Mediterranean University (3/6/21, March 2023) and the University Hospital of Heraklion (103 (142)/8 April 2023 and 10744/30 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Precautions were taken to protect participants’ privacy and anonymity, as well as the confidentiality of their data. Furthermore, participants were provided with and signed a relevant informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their voluntary participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hibbard, J.H.; Stockard, J.; Mahoney, E.R.; Tusler, M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health services research 2004, 39, 1005–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Wilczynski, N.; Navarro, T.; Hobson, N.; Jeffery, R.; Keepanasseril, A.; Agoritsas, T.; Mistry, N.; Iorio, A.; Jack, S. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, H.A.; Broman, A.T. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. British journal of ophthalmology 2006, 90, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, M.S.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Baker, D.W. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Archives of internal medicine 2005, 165, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.K.; Homme, R.P.; Stanisic, D.; Tyagi, S.C.; Singh, M. Protecting the aging eye with hydrogen sulfide. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 2021, 99, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.C.; Cheng, C.Y. Associations between chronic systemic diseases and primary open angle glaucoma: An epidemiological perspective. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 2017, 45, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DS, F. Doctor-patient communication, health-related beliefs, and adherence in glaucoma. Results from the Glaucoma Adherence and Persistency Study. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J.C.; McClure, C.A.; Ramos, S.E.; Schlundt, D.G.; Pichert, J.W. Compliance barriers in glaucoma: A systematic classification. Journal of glaucoma 2003, 12, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geitona, M.; Latsou, D.; Toska, A.; Saridi, M. Polypharmacy and adherence among diabetic patients in Greece. The Consultant Pharmacist® 2018, 33, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliarou, M.; Bakola, E.; Nikolentzos, A.; Sarafis, P. Reliability and validity of the Greek translation of the patient assessment of chronic illness care+(PACIC-PLUS GR) survey. BMC Family Practice 2020, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilleos, M.; Merkouris, A.; Charalambous, A.; Papastavrou, E. Medication adherence, self-efficacy and health literacy among patients with glaucoma: A mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ open 2021, 11, e039788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, K.W.; Lee, P.P. Health literacy and ophthalmic patient education. Survey of ophthalmology 2010, 55, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, P.J.; Buhrmann, R.; Quigley, H.A.; Johnson, G.J. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. British journal of ophthalmology 2002, 86, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, P.J.; Buhrmann, R.; Quigley, H.A.; Johnson, G.J. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol 2002, 86, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pelikan, J.M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC public health 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, A.; Middleton, N.; Charalambous, A.; Papastavrou, E. The association of health literacy and electronic health literacy with self-efficacy, coping, and caregiving perceptions among carers of people with dementia: Research protocol for a descriptive correlational study. JMIR research protocols 2017, 6, e8080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikan, J.; Ganahl, K. Die Europäische Gesundheitskompetenz-Studie: Konzept. Instrument und ausgewählte Ergebnisse 2017.

- Tsichla, L.; Patelarou, E.; Detorakis, E.; Tsilimparis, M.; Skatharoudi, C.; Kalaitzaki, M.; Garedaki, Ε.; Giakoumidakis, K. Translation and Validation of the Greek Version of the Patient Activation Measure-13 in Glaucoma Patients. Hellenic Journal of Nursing, 2024, 63, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Mahoney, E.R.; Stockard, J.; Tusler, M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health services research 2005, 40, 1918–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moljord, I.E.O.; Lara-Cabrera, M.L.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Rivero-Santana, A.; Eriksen, L.; Linaker, O.M. Psychometric properties of the Patient Activation Measure-13 among out-patients waiting for mental health treatment: A validation study in Norway. Patient Education and Counseling 2015, 98, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insignia Health, L. Patient Activation Measure (PAM) 13 License Materials. 2011.

- Hernandez, L.; French, M.; Parker, R. Roundtable on health literacy: Issues and impact. In Health Literacy; IOS Press: 2017; pp. 169–185.

- Chen, X.; Zhong, Y.-L.; Chen, Q.; Tao, Y.-J.; Yang, W.-Y.; Niu, Z.-Q.; Zhong, H.; Cun, Q. Knowledge of glaucoma and associated factors among primary glaucoma patients in Kunming, China. BMC ophthalmology 2022, 22, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. Journal of general internal medicine 2012, 27, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.; Rega, M.L.; Casasanta, D.; Graffigna, G.; Damiani, G.; Barello, S. The association between patient activation and healthcare resources utilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2022, 210, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; European, C.H.L.P. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC public health 2012, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledford, C.J.; Cafferty, L.A.; Russell, T.C. The influence of health literacy and patient activation on patient information seeking and sharing. Journal of health communication 2015, 20, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, R.E.; Moeykens, B.A.; Colton, T.C. Health and Literacy: A Review of Medical and Public Health Literature. Office of Educational Research and Improvement 1999. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, D. Helping people help themselves: A review of the evidence considering whether it is worthwhile to support self-management; Health Foundation: 2011.

- Mackert, M.; Mabry-Flynn, A.; Champlin, S.; Donovan, E.E.; Pounders, K. Health literacy and health information technology adoption: The potential for a new digital divide. Journal of medical Internet research 2016, 18, e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantwill, S.; Diviani, N. Health literacy and health disparities: A global perspective. In International Handbook of Health Literacy; Policy Press: 2019; pp. 139–152.

- McCleary-Jones, V. Health literacy and its association with diabetes knowledge, self-efficacy and disease self-management among African Americans with diabetes mellitus. ABNF Journal 2011, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: Better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health affairs 2013, 32, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health promotion international 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.S.; Feinglass, J.; Thompson, J.; Baker, D.W. In search of ‘low health literacy’: Threshold vs. gradient effect of literacy on health status and mortality. Social science & medicine 2010, 70, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersten, R.; Baker, S.K.; Shanahan, T.; Linan-Thompson, S.; Collins, P.; Scarcella, R. Effective Literacy and English Language Instruction for English Learners in the Elementary Grades. IES Practice Guide. NCEE 2007-4011. What Works Clearinghouse 2007.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).