1. Introduction

Recently, magnitude of 2.0 or more earthquakes on the Richter scale have occurred in South Korea, including the Gyeong-Ju earthquake (September 12, 2016) and Po-Hang magnitude of 5.4 Richter scale earthquake (November 15, 2017), the largest observed earthquakes in South Korea [

1,

2]. Based on the Earthquake and Disaster Countermeasures Act enacted in 2009, the 2017 earthquake-resistance design standards were revised in South Korea, and their application to all structures was announced. However, the social infrastructure structures built before the enforcement decree were still vulnerable to seismic load. The necessity for maintenance and reinforcement of earthquake-vulnerable RC structures is increasing [

3]. The seismic resistance effect of newly developed stiff-type polyurea (STPU) for the maintenance and reinforcement of RC structures was verified through experiments [

4].

Research on the reinforcement performance evaluation of structures enhanced with Polyurea has been conducted by on experiments and FEM simulations. Samiee et al. (2013) examined the explosive load resistance of a steel plate reinforced with PU using the LS-DYNA explicit finite element analysis program [

5]. When the coating thickness of PU exceeded 2 mm, better reinforcing effects were achieved when PU reinforcement was applied to the other side of a steel plate subjected to explosive loads. Parniani and Toutanji (2015) performed a flexural load test and evaluated the fatigue performance of PU-coated RC beams. In the flexural load test, the PU 5 mm-coated RC beam (P-B-M-2), PU 2.5 mm-coated RC beam (P-B-M-1), and the uncoated RC beam (C-M-B) demonstrated superior performance in that order, validating the reinforcing effect of PU for flexural loads. The difference in fatigue performance between PU with thicknesses of 2.5 mm and 5 mm was not significant, indicating that both thicknesses have almost identical behavior under fatigue load conditions [

6]. Wang et al. (2017) evaluated the blast resistance of masonry walls reinforced with PU. PU reinforcement enhanced blast resistance by 4.5–11 times [

7]. Song et al. (2020) reinforced RC columns using glass fiber-reinforced polyurea (GFRPU) and measured the shear strength under quasistatic cyclic loading. The shear strength of the GFRPU-reinforced columns was approximately 8.7% greater than that of the unreinforced RC columns [

8].

In this paper, FE model is constructed for RC columns reinforced with STPU using the experimental data from Lee et al. (2022) paper. Building FE modelling in dynamic inelastic analysis is an important tool for the evaluation of the performance of RC structures under strong earthquakes. FE modelling. FE analysis allow for reducing the cost associated with experiments and enables the identification of other factors that may not have been observable during experimentation [

9]. In this paper, 3D FE model was constructed using ABAQUS, and calibration of the FE model was conducted using the experimental data from Lee et al. (2022) paper. With the calibrated model, the extent of damage for each specimen was assessed to compare and analyze the reinforcement performance under seismic load.

Lee et al. (2022) presented the seismic performance evaluation of RC column retrofitted by STPU through pseudo-dynamic and shaking table tests. In this paper, the seismic reinforcement performance of STPU was evaluated by developing a 3D FE model based on the experimental results. All the notations from the Lee et al. (2022) paper will be retained.

3. Verification of Numerical Analysis Results

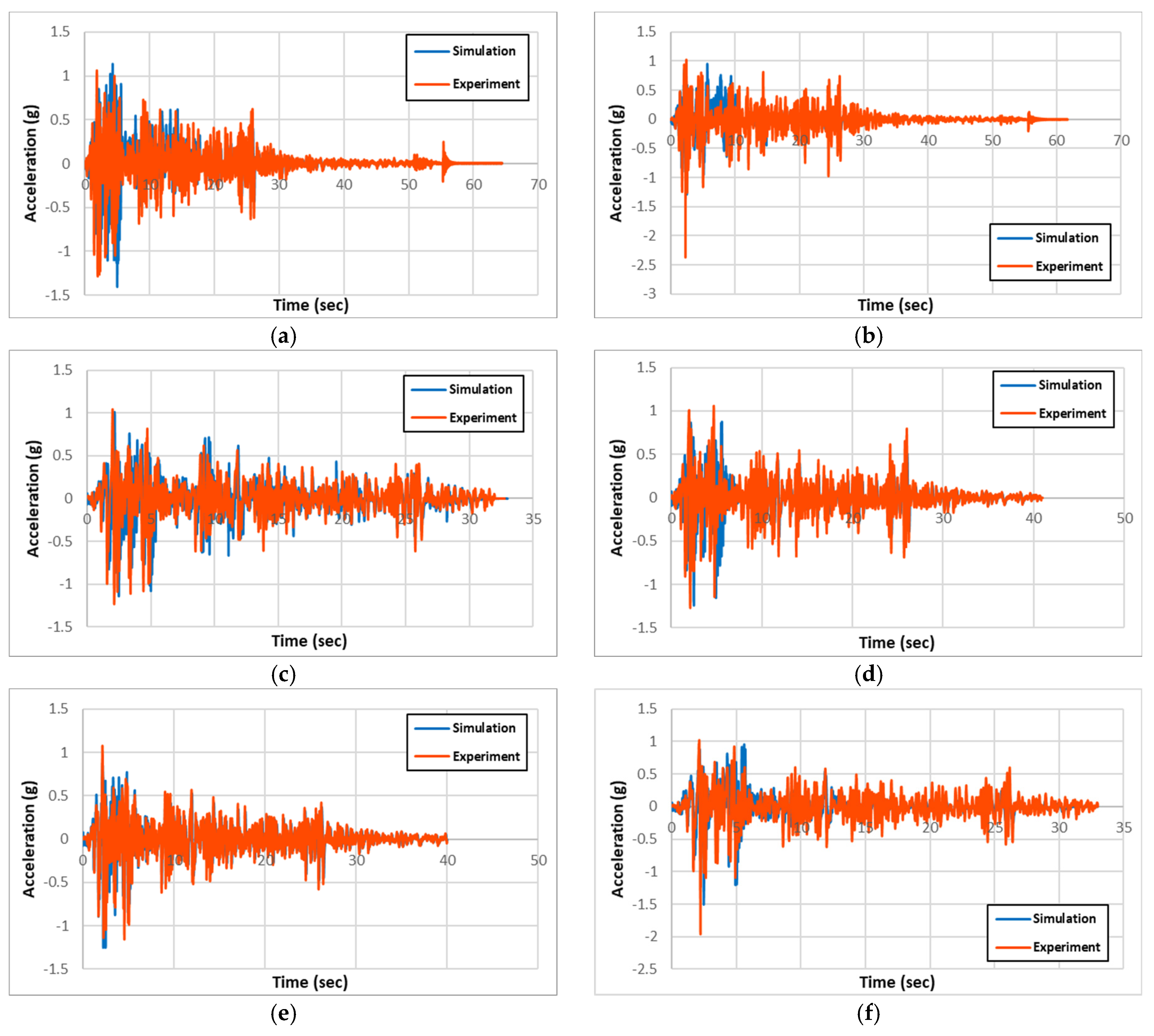

Based on the experimental results, the simulations are performed. The objective of the simulation work is to quantify the strengthening effect of the application of PU on RC columns under seismic loading. For the calibration of the simulation model, the simulation and experimental results of maximum and minimum deflection, acceleration, and maximum and minimum strain in longitudinal rebars are compared. As shown in

Figure 4, the locations where the acceleration and rebar strain results obtained for both the experiments and simulations are identical.

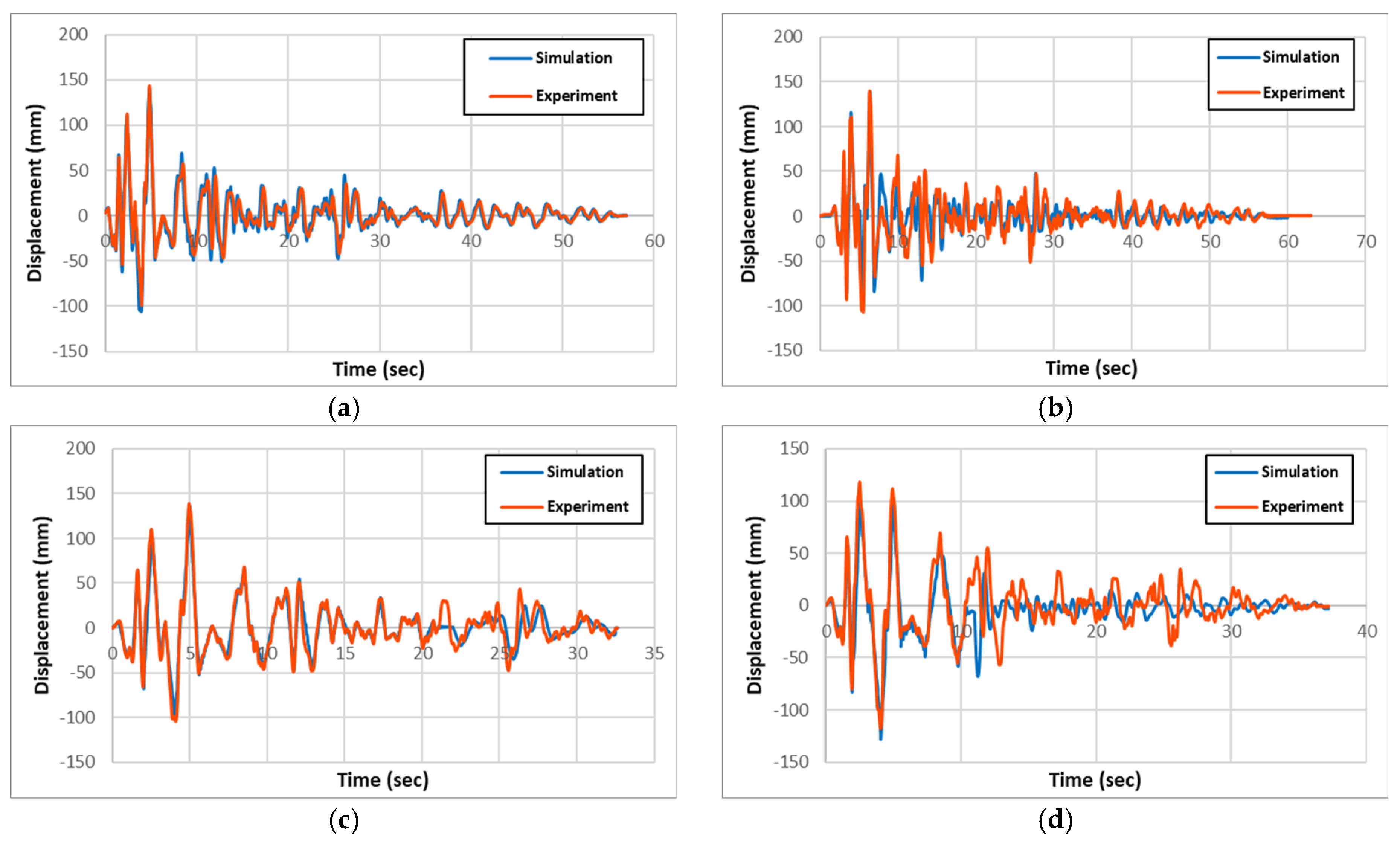

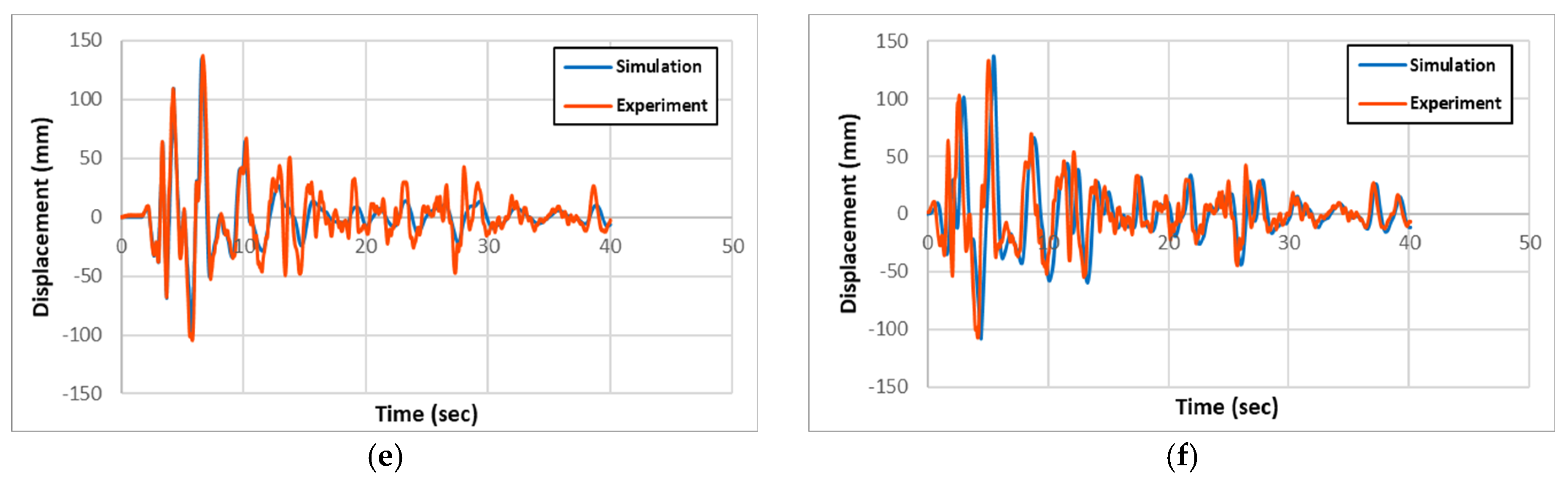

The experimental and numerical results for acceleration, displacement, and longitudinal rebar strain history for all specimen types are presented and compared in

Figure 5,

Figure 6, and

Figure 7, respectively. Also, the maximum column head displacements and longitudinal rebar strains from the experimental and simulation results for all of the specimen types are summarized in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively. From the comparison of the experimental and simulation results, two significant conclusions can be drawn. One is that the experimental and simulation displacement and strain results are similar within 3% and 14%, respectively, validating precision of the simulation model.

From the result comparison, the column head displacements between circular and rectangular columns from both experiments and simulation are relatively same. Also, the comparison between the non-strengthened RC columns to the strengthened PU and GFPU columns showed that non-strengthened ones had slightly larger displacements in both circular and rectangular columns.

However, the longitudinal rebar strain results show that the circular columns have approximately 2 folds of strains than the rectangular columns from both the experiments and simulations. This trend can be attributed to the fact that the circular columns have much better seismic resisting capacity than the rectangular columns from having much larger effective stress resisting cross-section area than the rectangular ones. When the stains of the circular columns are compared, the non-strengthened RC had approximately 2100~2400με, PU only strengthened one had approximately 1400~1600με, and PU and GFRP strengthened one had approximately 600με. This result trend is logical since the GFPU strengthening is more effective than the PU only strengthening from GFRP applying more confinement and stiffness to the core RC columns than PU only applied condition. In the rectangular columns, the non-strengthened RC showed approximately 4 times more strain than the strengthened ones caused by large crack damages along the column compared to the concentrated damage at the base joint region in PU and GFPU strengthened columns, which are reflected by the strain results in

Table 3.

To quantitatively analyze the reinforcement effect through the previously constructed analytical model, the lateral shear force–displacement relationship of specimens reinforced with PU and GFRP was compared. In order to increase the effectiveness of the reinforcement effect analysis, the criteria were set through the PEEQ parameter, which is the failure criteria of the concrete material model that occurred at 450 mm point (1/2 point of reinforcement position) from the bottom of the test specimen. The stiffness of the structure was analyzed by the ratio of shear force for each specimen based on the later displacement when concrete failure first occurred in the reinforced RC test specimen. As shown in the following

Figure 8, both rectangular cross-section specimens and circular cross-section specimens showed a trend of increasing load on the structure compared to the same displacement in the order of GFPU>PU>RC. As a result of comparing the stiffness of the structure through slope, improvements of 15.04 and 24.46% compared to the non-reinforced specimen were confirmed at R-RC 31.26, R-PU 35.96, and R-GFPU 41.54, respectively, and improvements of 21.35 and 31.75% were confirmed at C-RC 31.53, C-PU 38.26, C-GFPU 41.54, respectively.

ABAQUS/Standard can show the progress of structural failure and deformation as dissipated energy (ALLDMD) through the structural damage criteria of the properties input in the analysis model. In general, if a structure has excellent rigidity and seismic performance, the energy that can be dissipated as the load action increases, resulting in high stability of the structure. Notably, the corresponding parameter has a proportional relationship to the failed material volume of the member when the same load is applied [

17]. The damage dissipated energy (ALLDMD, M_D) can be calculated using Equation (6).

In the formula, represents the duration of ground motion, is the material volume, is the stress, is the cracking strain.

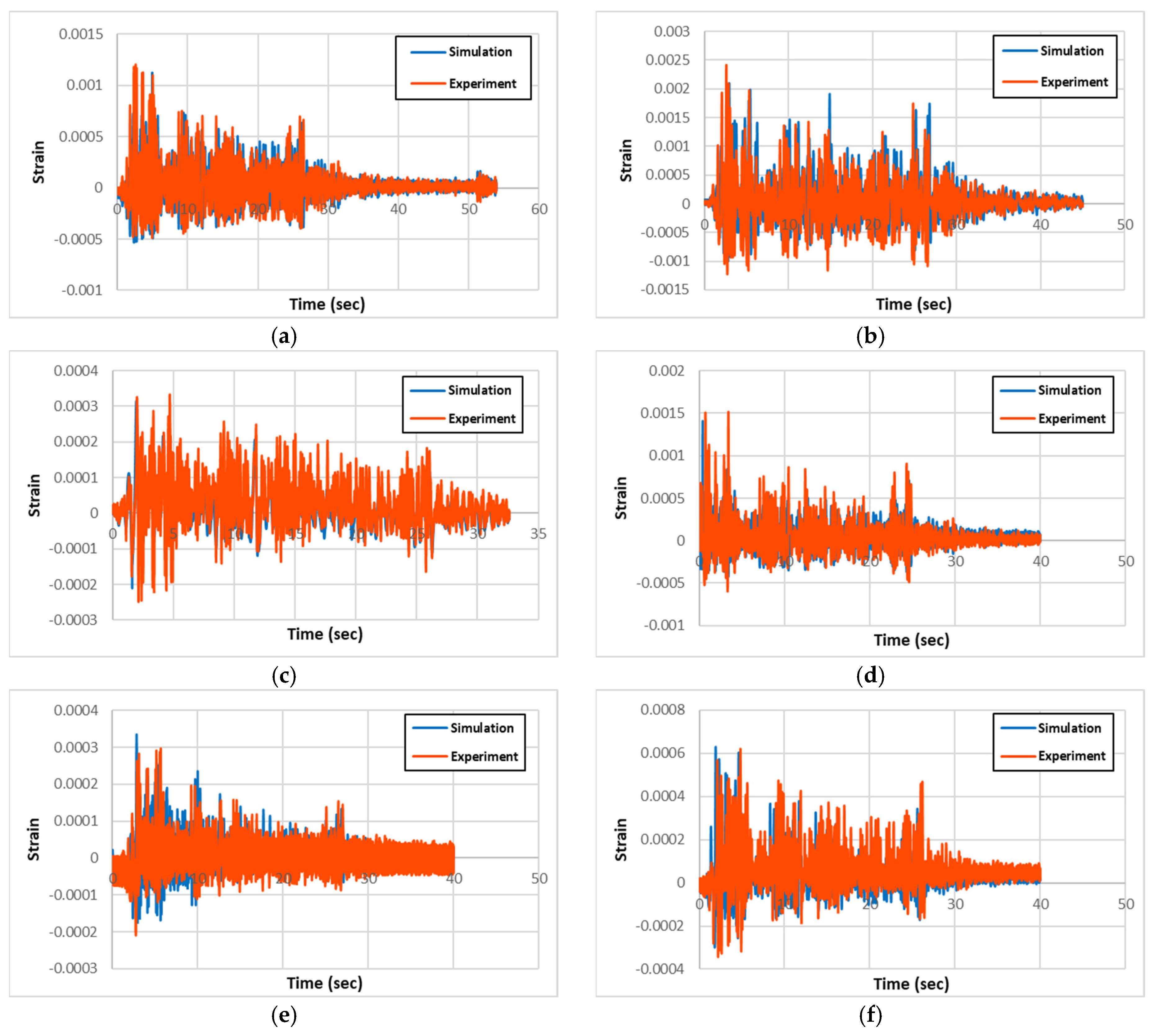

Figure 9 presents the comparison of the ALLDMD graphs for all specimens, with data up to the initial 10 sec considered to show the macroscopic differences. According to the data, the energy dissipated when the specimen was destroyed was compared for different reinforcement methods. As shown in

Figure 9, critical failure occurred in the specimen between 2 and 6 secs when the maximum seismic load was applied. Since the failure of the specimen against compression and tensile stress occurs repeatedly due to the characteristics of the seismic loading, it is necessary to analyze the reinforcing effect of the reinforcing material based on a specific period. To analyze the initial loss of the stiffness of the specimen, the dissipated energy of the specimen according to each cross-sectional shape was compared based on the time of initial concrete destruction.

Table 4 lists the range of dissipated energy values with this period. Compared to the non-reinforced circular column, the circular cross-section specimen showed a reduction with the range of dissipated energy values of 76% and 82% when PU and GFPU reinforcement were applied, respectively. Compared to the non-reinforced rectangular column, the rectangular cross-section specimen showed a reduction with the range of dissipated energy values of 80% and 60% when PU and GFPU reinforcement were applied, respectively. It is defined as both PU and GFPU reinforcement causing damage due to stress concentration due to repeated loads as the PU was torn off from the corner without a single movement of the PU and GFRP sheets. For a circular cross-sectional specimen without edges, it is defined as that the circular cross-sectional specimen has superior energy dissipation ability than the prismatic cross-sectional specimen due to the formation of a discontinuous surface in the synthesis of PU.

To explain the difference in the trend of the dissipated energy for the different cross-sectional PU and GFPU reinforced specimens, the von Mises stress distribution of each specimen and degree of concrete fracture were compared at the specific time that the first concrete failure occurred, which has come up with ALLDMD. PEEQ was used to visualize cracks in the concrete elements with the CDP model used as the material model of concrete.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the distribution of the von Mises stress and PEEQ for each specimen. As in the case of the ALLDMD graph, considerable stress occurred in the circular cross-section specimen. In addition, similar to the trend of the dissipated energy, for the square specimens, a wider distribution and larger stress occurred in the GFPU reinforced specimen than those in the PU reinforced specimen. The contrasting trend was observed for the circular specimen.

The CDP model used as a concrete material model is a continuum damage model based on plastic deformation of concrete. The model assumes tensile cracking and compressive crushing as the main fracture mechanisms of concrete elements. The progression of concrete cracking is controlled by two hardening parameters, which mean tensile and compressive equivalent plastic strains (PEEQ, ε_t^(~ pl), ε_c^(~ pl)), both of which are the major failure mechanisms mentioned above. It is affected by tensile and compressive forces. The concrete damage plasticity model has no concept that cracks occur at the integration point of the mesh using the material model. Therefore, the concept of effective crack direction can be introduced for the purpose of graphic visualization of crack patterns in concrete specimens. Various criteria have been studied to define the crack direction. In this study, the concept of crack initiation of concrete is used at the integration point where the equivalent plastic strain (PEEQ) is greater than zero, proposed by Lubliner et al (1989) [

18]. Also, the concept assumes that the propagation direction of cracks is parallel to the propagation direction of equivalent plastic strain (PEEQ) [

14,

19,

20]. Through this, the concrete cracks of each specimen were evaluated.

The PEEQ output parameter indicated that the crack occurrence decreased in the order of RC, PU, GFPU when comparing the crack height that progressed in the upper direction of the column from the expected concrete fracture (foundation and column starting point). It was confirmed that crack heights of 454 mm and 450 mm were generated in the case of R-PU and R-GFPU, respectively, and crack heights of 425 mm and 400 mm were generated in the case of C-PU and C-GFPU, respectively. As mentioned previously, it can be analyzed that in the case of a rectangular cross-section specimen, discontinuous edges that exist on the surface of the specimen have led to insufficiency of reinforcement effect to the reinforcement material compared to the circular cross-sectional test specimen.

Through this approach, it is possible to quantitatively evaluate the degree of structural destruction in the context of the reinforcement effect, and the findings can provide valuable guidance for selecting the optimal reinforcement construction method for actual structures.

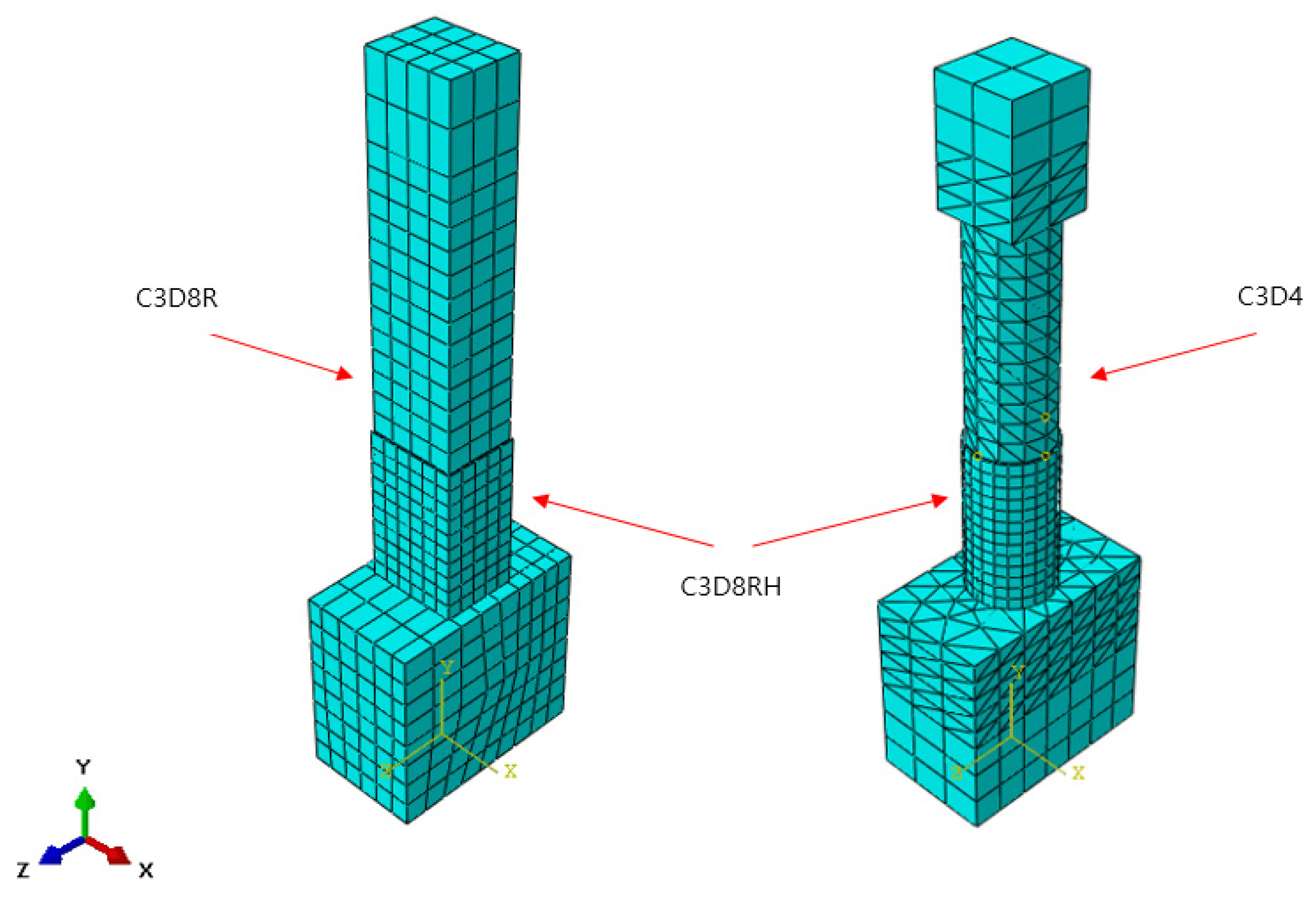

Figure 1.

Finite element meshing.

Figure 1.

Finite element meshing.

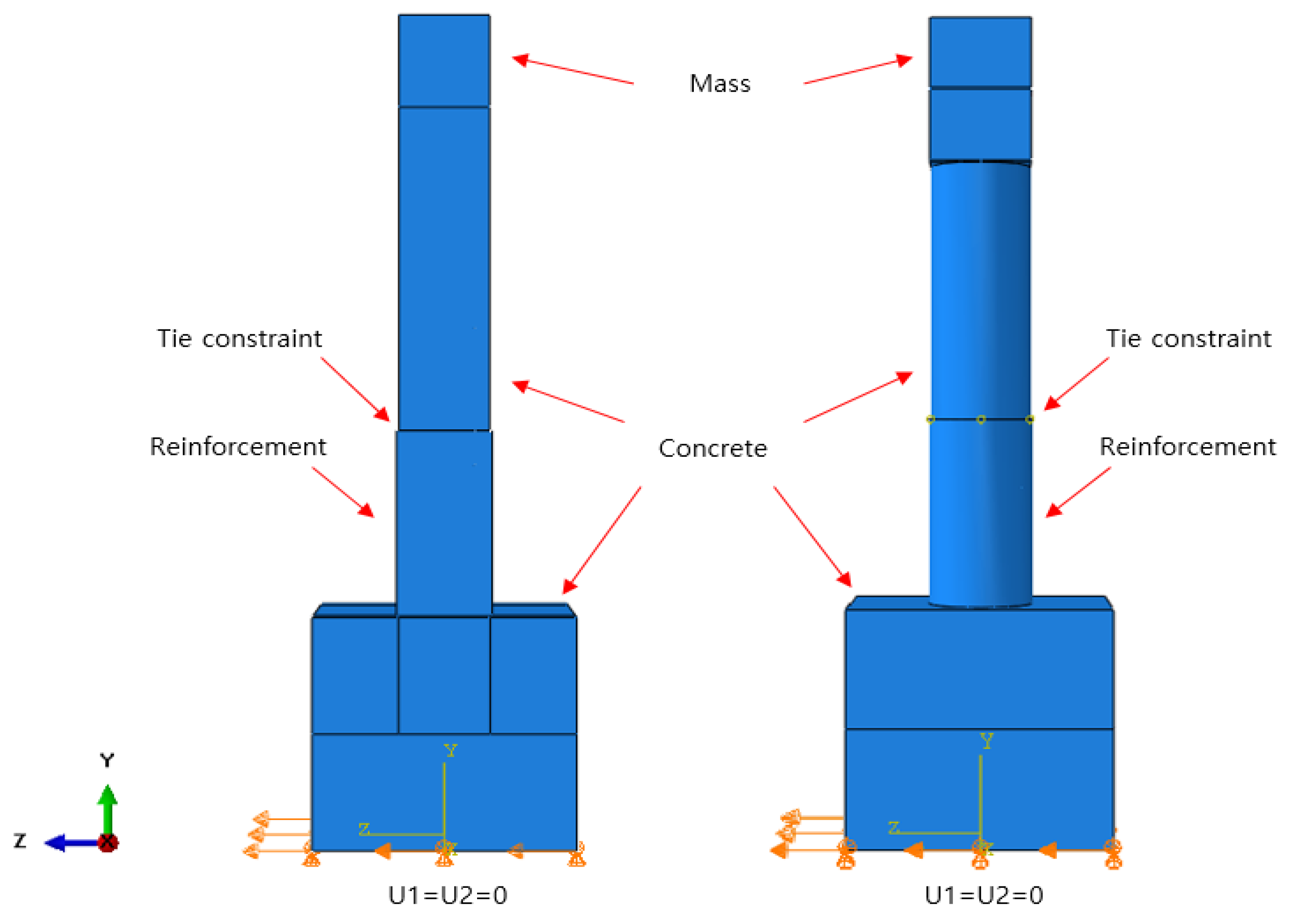

Figure 2.

Loading and boundary condition.

Figure 2.

Loading and boundary condition.

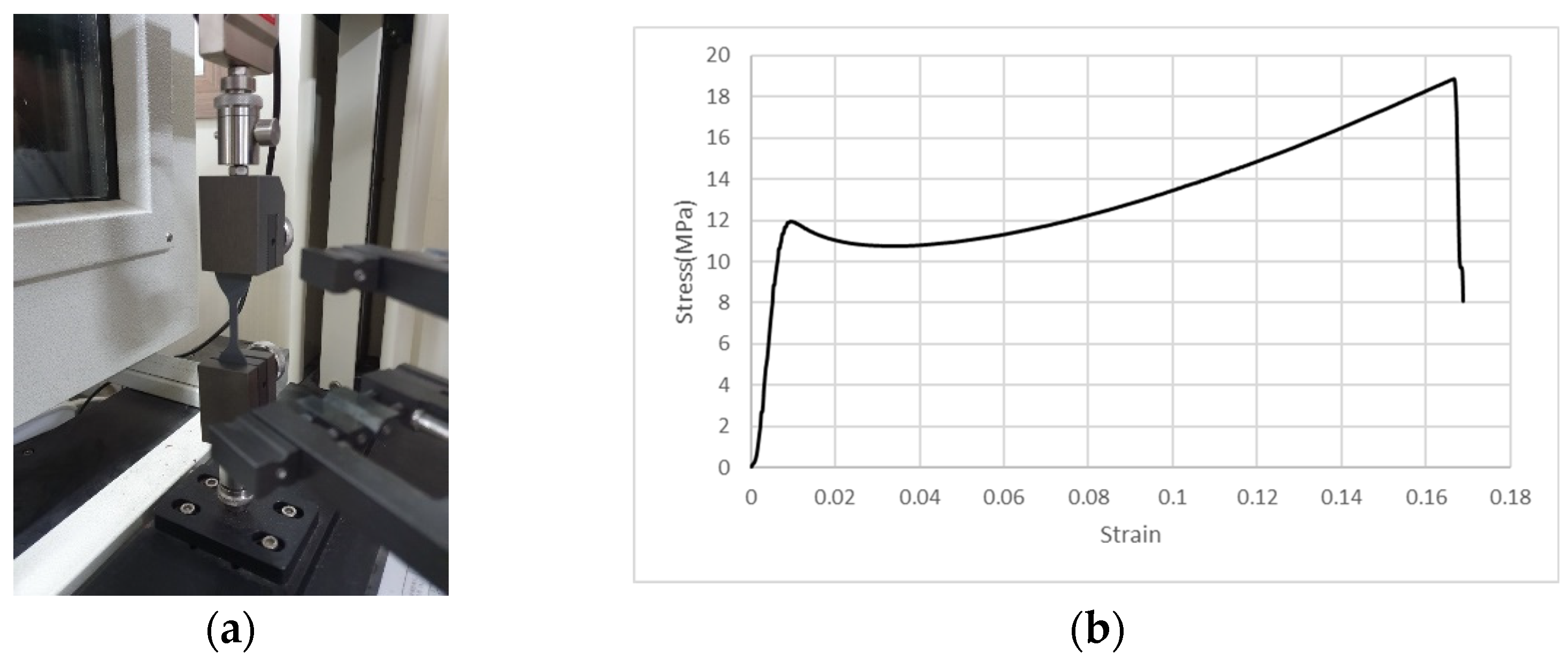

Figure 3.

Material evaluation of PU: (a) Uniaxial tensile test of Polyurea; (b) Stress-Strain curve to evaluate hyperelastic material.

Figure 3.

Material evaluation of PU: (a) Uniaxial tensile test of Polyurea; (b) Stress-Strain curve to evaluate hyperelastic material.

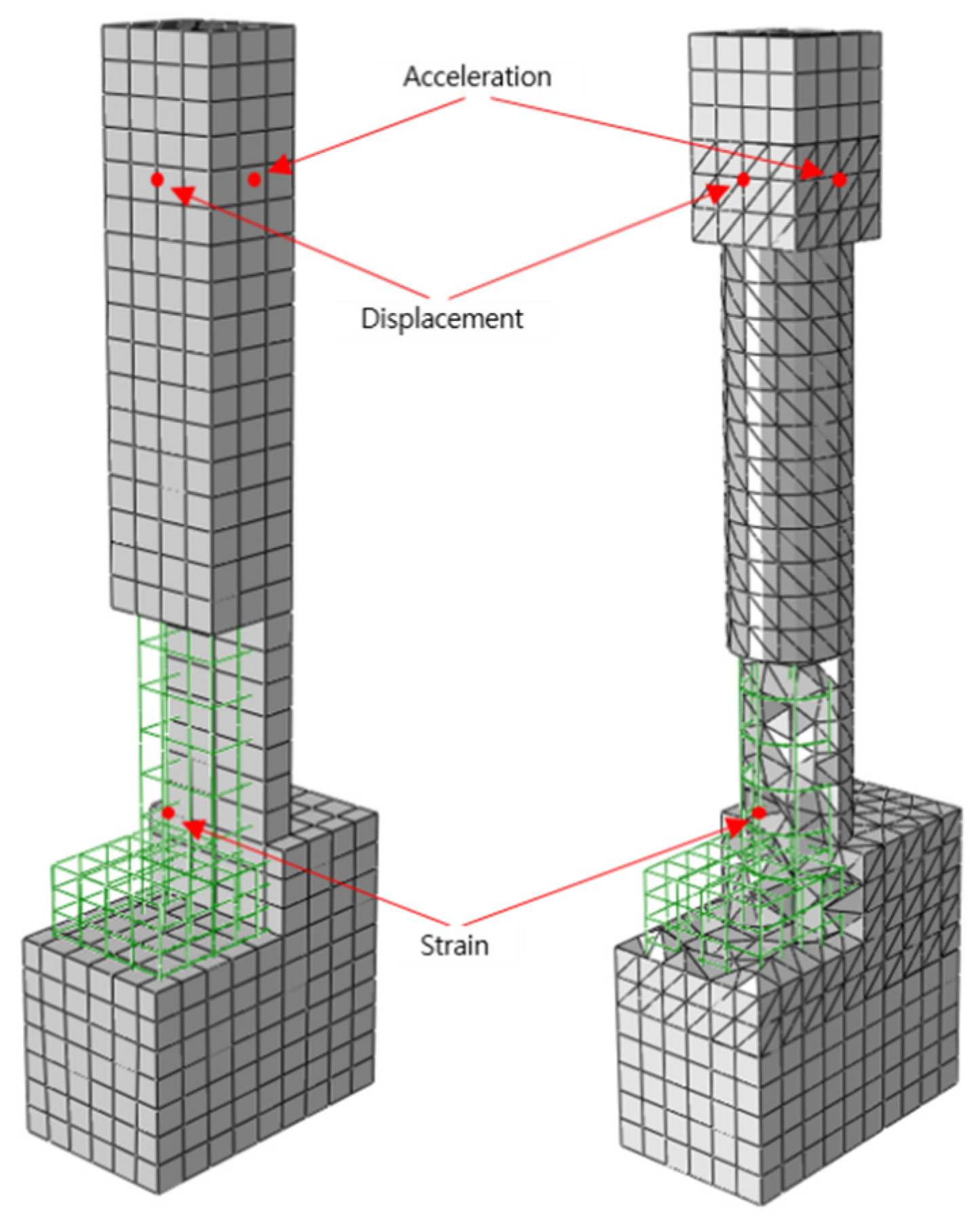

Figure 4.

Comparison point for experimental and numerical results.

Figure 4.

Comparison point for experimental and numerical results.

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimental and simulation acceleration: (a) R-RC; (b) C-RC; (c) R-PU; (d) C-PU; (e) R-GFPU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 5.

Comparison of experimental and simulation acceleration: (a) R-RC; (b) C-RC; (c) R-PU; (d) C-PU; (e) R-GFPU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 6.

Comparison of experimental and simulation displacement: (a) R-RC; (b) C-RC; (c) R-PU; (d) C-PU; (e) R-GFPU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 6.

Comparison of experimental and simulation displacement: (a) R-RC; (b) C-RC; (c) R-PU; (d) C-PU; (e) R-GFPU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 7.

Comparison of experimental and simulation strain: (a) R-RC; (b) C-RC; (c) R-PU; (d) C-PU; (e) R-GFPU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 7.

Comparison of experimental and simulation strain: (a) R-RC; (b) C-RC; (c) R-PU; (d) C-PU; (e) R-GFPU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 8.

Force-displacement response and comparison of stiffness: (a) Rectangular cross-section specimen; (b) Circular cross-section specimen.

Figure 8.

Force-displacement response and comparison of stiffness: (a) Rectangular cross-section specimen; (b) Circular cross-section specimen.

Figure 9.

ALLDMD for column specimen using reinforcement method as the variable: (a) Rectangular cross-section; (b) Circular cross-section.

Figure 9.

ALLDMD for column specimen using reinforcement method as the variable: (a) Rectangular cross-section; (b) Circular cross-section.

Figure 10.

von-Mises stress distribution: (a) R-RC; (b) R-PU; (c) R-GFPU; (d) C-RC; (e) C-PU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 10.

von-Mises stress distribution: (a) R-RC; (b) R-PU; (c) R-GFPU; (d) C-RC; (e) C-PU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 11.

Effective plastic strain, PEEQ distribution: (a) R-RC; (b) R-PU; (c) R-GFPU; (d) C-RC; (e) C-PU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Figure 11.

Effective plastic strain, PEEQ distribution: (a) R-RC; (b) R-PU; (c) R-GFPU; (d) C-RC; (e) C-PU; (f) C-GFPU. * RC: Non-strengthened, C-: Circular column, R-: Rectangular column.

Table 1.

Material Property for Concrete Damage Plasticity.

Table 1.

Material Property for Concrete Damage Plasticity.

|

Elastic Modulus (MPa) |

|

ψ |

|

|

|

|

| 2400 |

27537 |

0.167 |

15 |

0.1 |

1.16 |

0.667 |

0.0005 |

Table 2.

Maximum displacement results of column head for all specimen types.

Table 2.

Maximum displacement results of column head for all specimen types.

| Specimen |

Column Head(mm) |

Difference Rate (%) |

| Experiment |

Simulation |

| R-RC |

140.17 |

143.39 |

2.6 |

| R-PU |

138.86 |

135.74 |

2.3 |

| R-GFPU |

137.41 |

135.06 |

1.7 |

| C-RC |

139.97 |

138.9 |

0.8 |

| C-PU |

118.37 |

128.26 |

8.4 |

| C-GFPU |

133.14 |

137.04 |

2.9 |

Table 3.

Maximum strain results of longitudinal rebar for all specimen types.

Table 3.

Maximum strain results of longitudinal rebar for all specimen types.

| Specimen |

Longitudinal rebar strain |

Difference Rate (%) |

| Experiment |

Simulation |

| R-RC |

1200 |

1124 |

6.3 |

| R-PU |

330 |

315 |

4.5 |

| R-GFPU |

300 |

335 |

11.7 |

| C-RC |

2420 |

2098 |

13.3 |

| C-PU |

1630 |

1407 |

13.7 |

| C-GFPU |

620 |

630 |

1.6 |

Table 4.

Range of ALLDMD and ratio comparison.

Table 4.

Range of ALLDMD and ratio comparison.

| Specimen |

Range of Dissipated Energy (J) |

Ratio |

| R-RC |

4.21 |

1.00 |

| R-PU |

0.85 |

0.20 |

| R-GFPU |

1.69 |

0.40 |

| C-RC |

5.26 |

1.00 |

| C-PU |

1.23 |

0.24 |

| C-GFPU |

0.97 |

0.18 |