Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Techniques

2.1. Preparation of Porous GaN Substrate

2.2. Preparation of Pure and N-Doped ZnO Films on GaN Substrate

2.3. Characterisation Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural and Optical Analysis of GaN Substrates

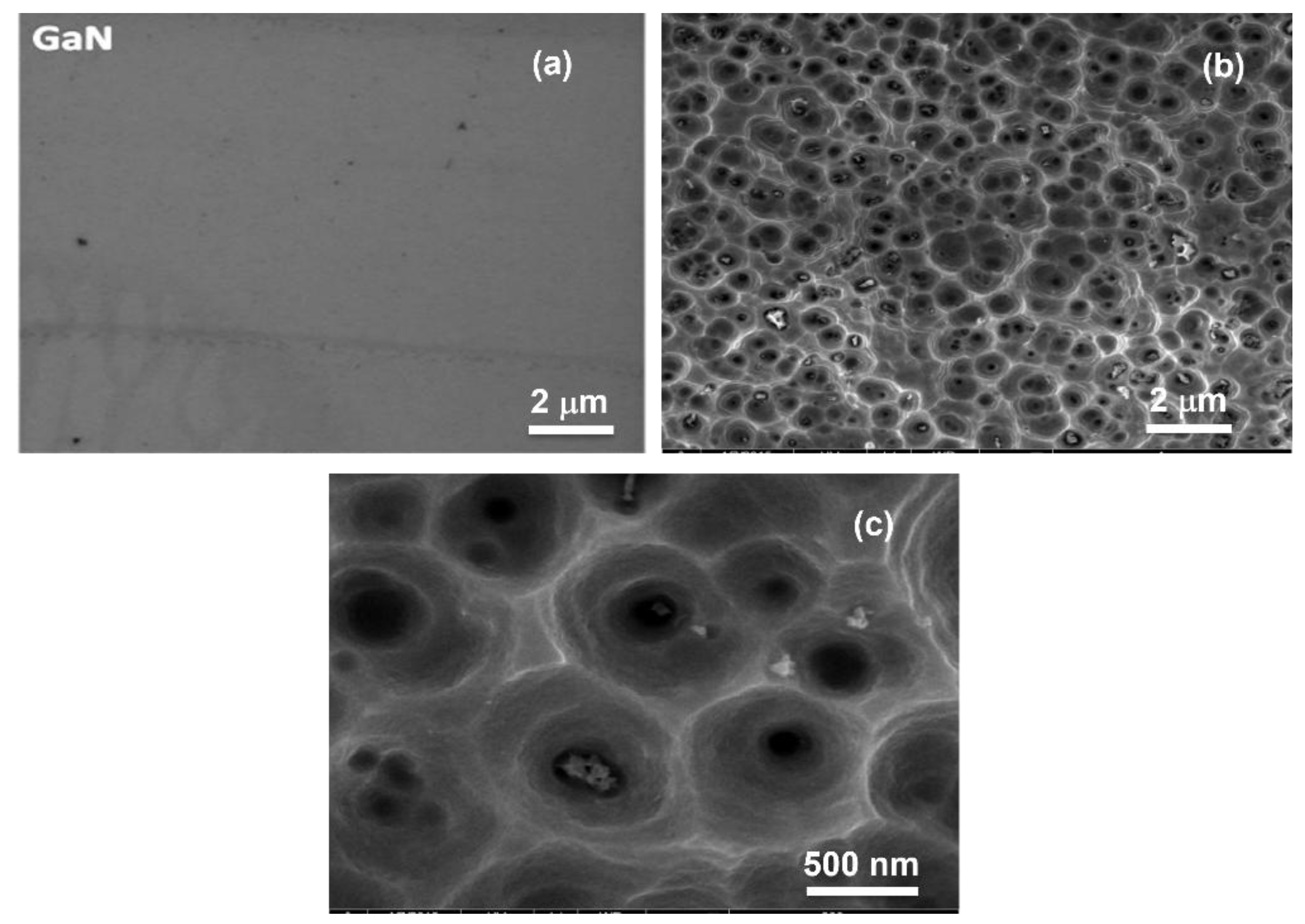

3.1.1. SEM Analysis of Pristine and Porous GaN Substrate

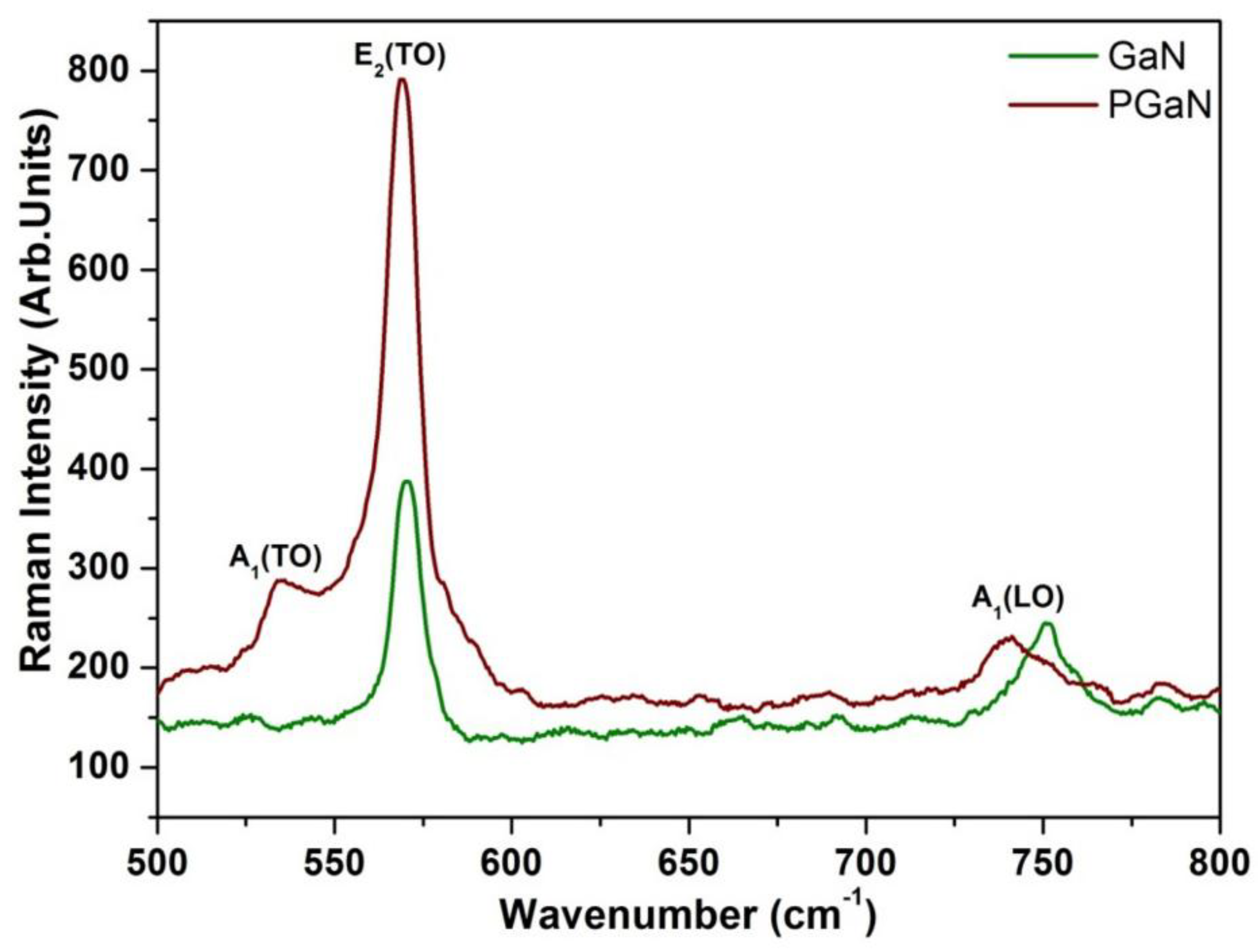

3.1.2. Raman Spectral Analysis of Pristine and Porous GaN Substrate

3.2. Structural, Morphological and Electrical Properties ZnO Films

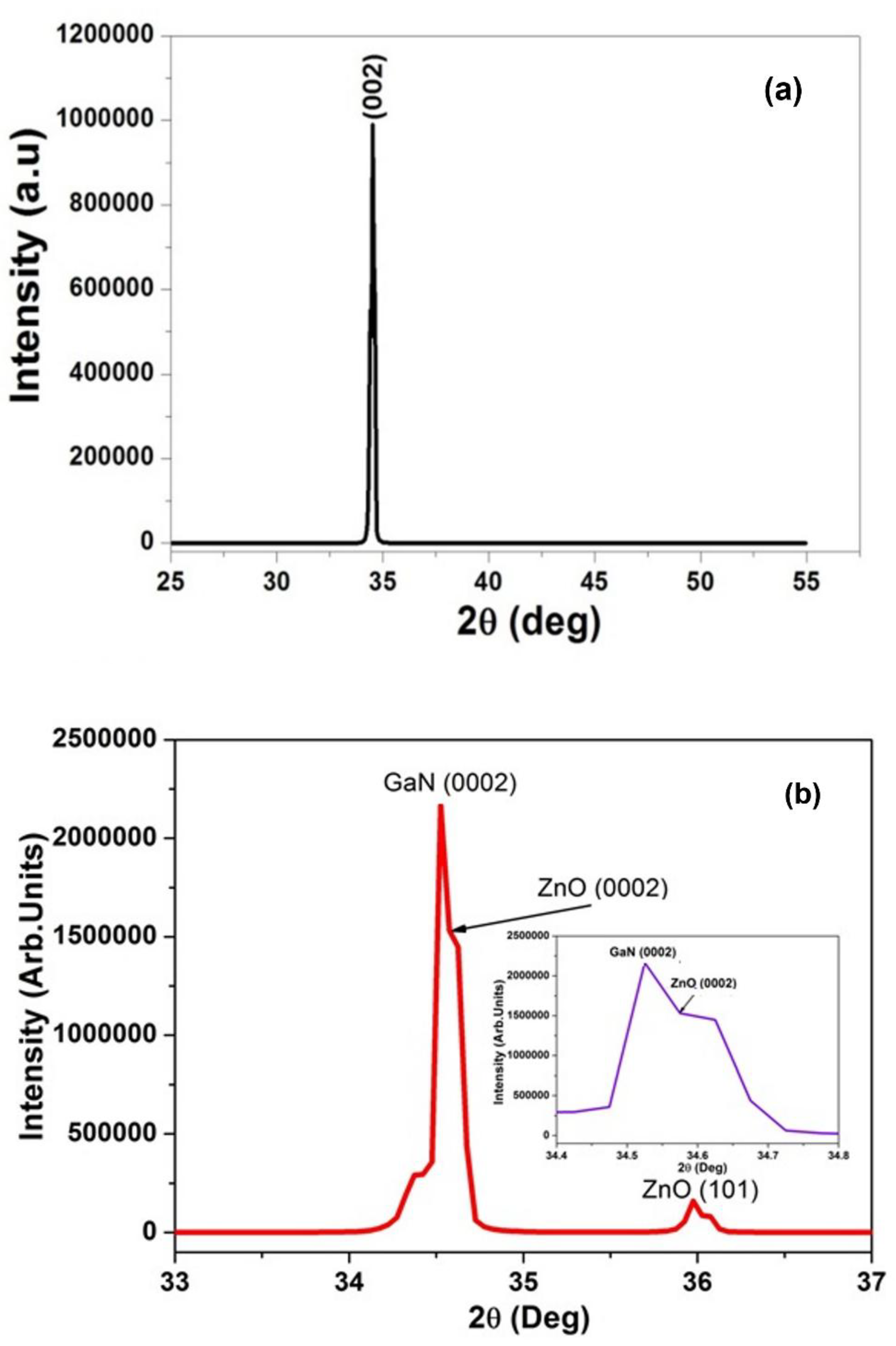

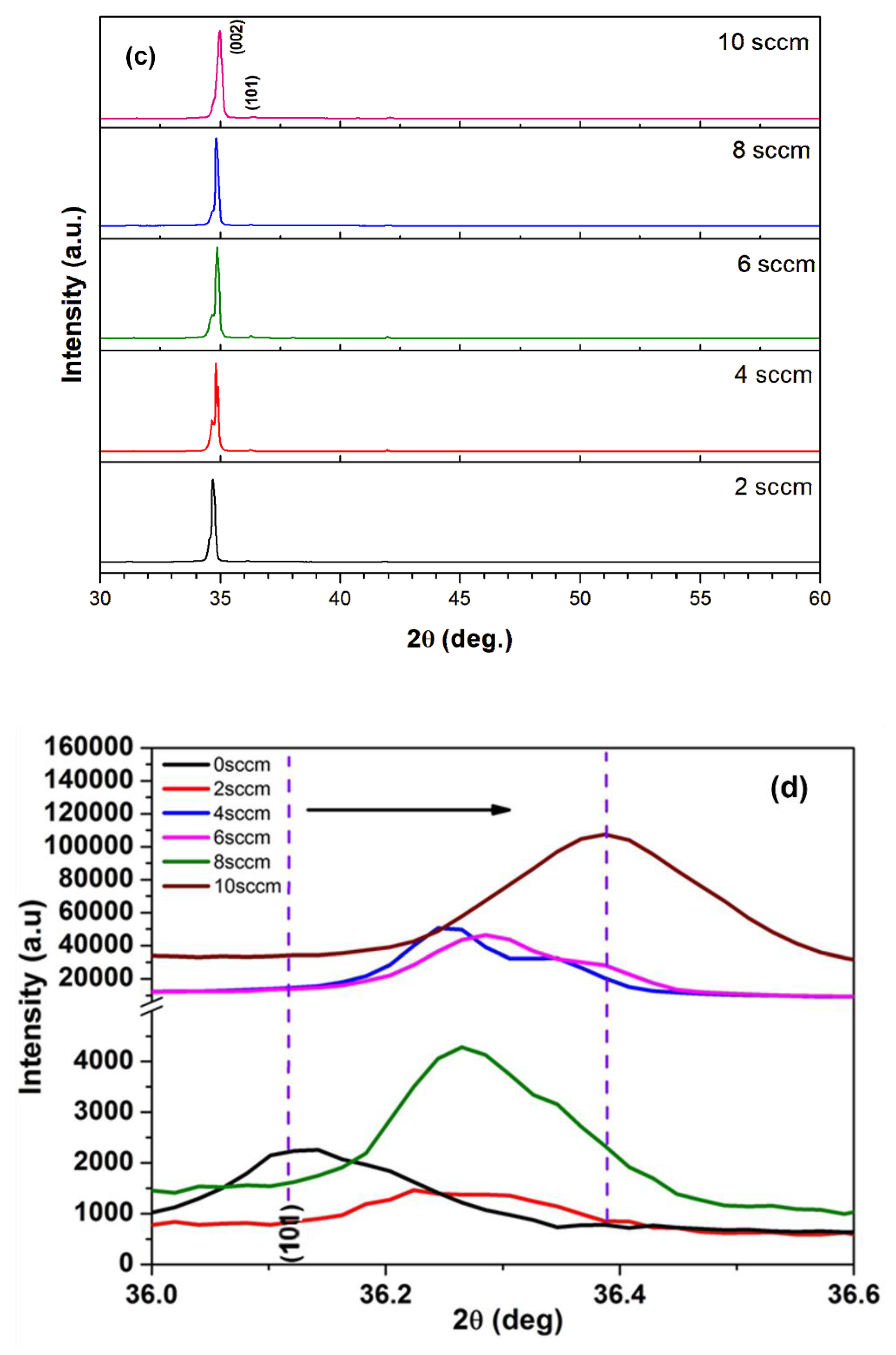

3.2.1. XRD Analysis of Pure and Nitrogen Doped ZnO on Porous GaN Substrate

3.2.2. SEM Analysis of Pure and Nitrogen Doped ZnO on Porous GaN Substrate

3.2.3. Atomic Force Microscopic Analysis of Pure ZnO and N-ZnO Films

3.2.4. Photoluminescence Analysis of ZnO Films on GaN Substrates

3.2.5. UV-Visible Specrtra of ZnO Films on GaN Template

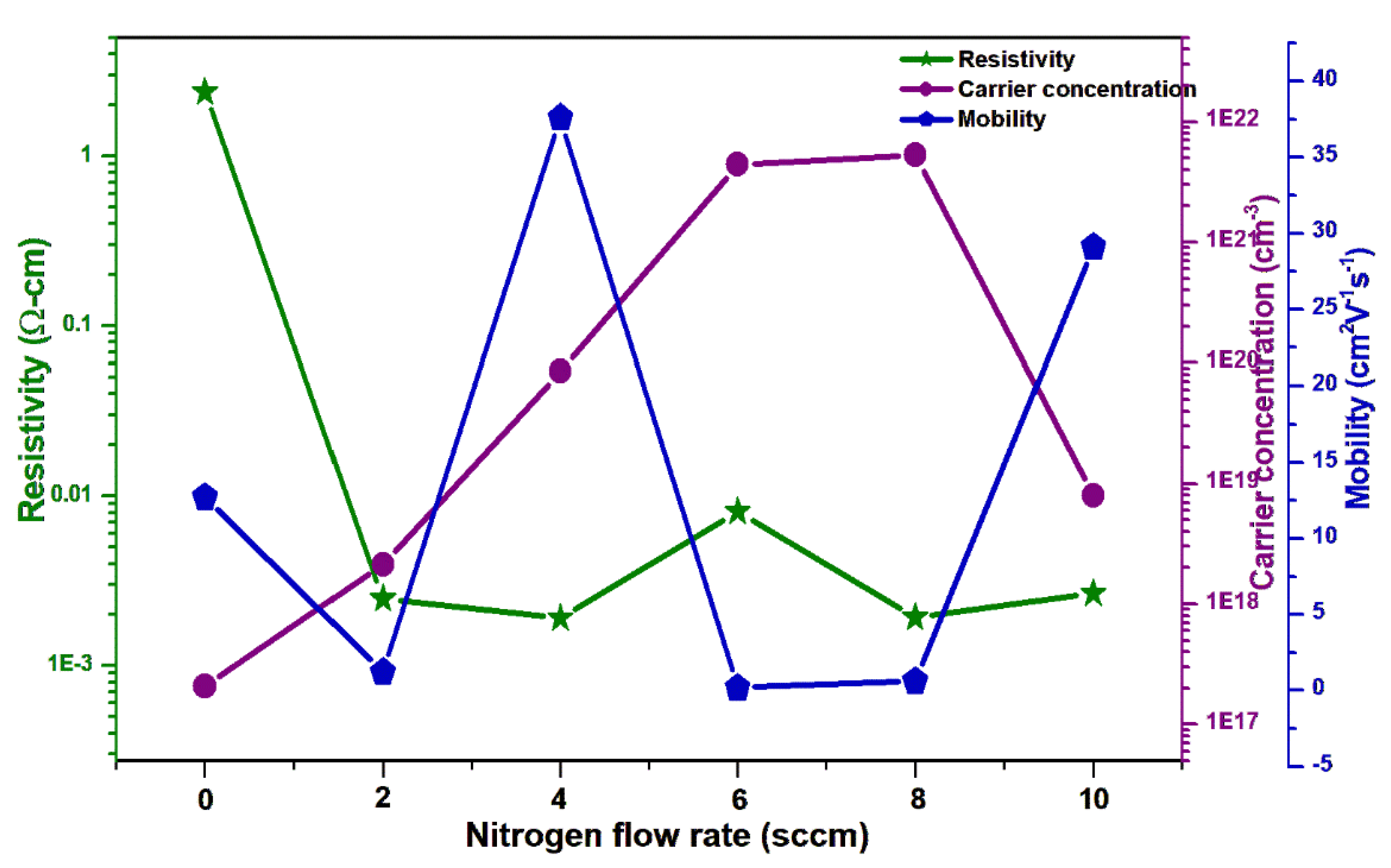

3.2.6. Electrical Properties of ZnO Films on GaN Substrate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, Z.R.; Voigt, J.A.; Liu, J.; Mckenzie, B.; Mcdermott, M.J.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Xu, H. Complex and oriented ZnO nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seghier, D.; Gislason, H.P. Shallow and deep donors in n-type ZnO characterized by admittance spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2008, 19, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingshirn, C. ZnO: Material, physics, and applications. ChemPhysChem. 2007, 8, 782–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.C.; Xu, C.S.; Qiu, Y.Q.; Zhao, L.; Rong, X.M. Effect of nitrogenized Si (111) substrates on the quality of ZnO films grown by pulsed laser deposition. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 035307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, E.; Barquinha, P.M.C.; Pimentel, A.C.M.B.G.; Gonçalves, A.M.F.; Marques, A.J.S.; Martins, R.F.P.; Pereira, L.M.N. Wide-bandgap high-mobility ZnO thin-film transistors produced at room temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 2541–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ko, H.J.; Hong, S.K.; Yao, T. Layer-by-layer growth of ZnO epilayer on Al2O3(0001) by using a MgO buffer layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 76, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgür, Ü.; Alivov, Ya. I.; Liu, C.; Teke, A.; Reshchikov, M.A.; Doğan, S.; Avrutin, V.; Cho, S.-J.; Morkoç, H. A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 98, 041301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanheusden, K.; Warren, W.L.; Seager, C.H.; Tallant, D.R.; Voigt, J.A.; Gnade, B.E. Mechanisms behind green photoluminescence in ZnO phosphor powders. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 7983–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearton, S.J.; Norton, D.P.; Ip, K.; Heo, Y.W.; Steiner, T. Recent progress in processing and properties of ZnO. Superlattices Microstruct. 2003, 34, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Zinc oxide nanostructures: Growth, properties, and applications. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2004, 16, R829–R858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, T. Basic Properties of ZnO, GaN, and Related Materials. In Oxide and Nitride Semiconductors. Advances in Materials Research, Yao, T.; Hong, S.K. Ed.; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2009, Volume 12.

- Chao, C.H.; Wei, D.H. Synthesis and characterization of high c-axis ZnO thin film by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition system and its UV photodetector application. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 3, 53097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, F. ; Yeadon, M.; Smith, D. J.; Tang, H.; Kim, W.; Salvador, A.; Botchkarev, A. E.; Gibsor, J. M.; Polyakov, A. Y.; Skowronski, M.; Morkoc, H. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 983.

- Dong, J.J.; Zhang, X.W.; Yin, Z.G.; Wang, J.X.; Zhang, S.G.; Liu, X. Ultraviolet electroluminescence from ordered ZnO nanorod array/p-GaN light emitting diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 171109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Look, D.C. Recent advances in ZnO materials and devices. Mater. Sci. Eng. B, 2001, 80, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, C.K.; Kuan, T.S.; Lee, C.D.; Sagar, A.; Feenstra, R.M.; Koleske, D.D.; Adesida, I. Growth of GaN on porous SiC and GaN substrates. J. Electron. Mater. 2003, 32, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, D.P.; Heo, Y.W.; Ivill, M.P.; Ip, K.; Pearton, S.J.; Chisholm, M.F.; Steiner, T. ZnO: Growth, doping, and processing. Mater. Today, 2004, 7, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. Nanopiezotronics. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiqul, I.M.; Deep, R.; Lin, J.; Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y. The Role of nitrogen dopants in ZnO nanoparticle-based light emitting diodes. Nanomaterials. 2022, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, E.; Privitera, A.; Chiesa, M.; Salvadori, E.; Paganini, M.C. Nitrogen-doped Zinc oxide for photo-driven molecular hydrogen production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musiliyu, K.A.; Ogunmola, E.D.; Ajayi, A.A.; Abodunrin, O.W. Effect of concentration on the properties of nitrogen-doped zinc oxide thin films grown by electrodeposition. Mater. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 2023, 12, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, R.; Hassan, Z. Effect of nitrogen doping on structural, morphological, optical and electrical properties of radio frequency magnetron sputtered zinc oxide thin films. Physica B Condens. Matter. 2016, 490, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.W.; Oh, C.S.; Cheong, H.S.; Yang, J.W.; Youn, C.J.; Lim, K.Y. UV-assisted electrochemical oxidation of GaN. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2002, 41, 1017–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Yam, F.K.; Hassan, Z.; Ng, S.S. Porous GaN prepared by UV assisted electrochemical etching. Thin solid films, 2007, 515, 3469–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, V.Y.; Kitaev, Y.E.; Goncharuk, I.; Smirnov, A.; Graul, J.; Semchinova, O.; Uffmann, D.; Smirnov, M.; Mirgorodsky, A.; Evarestov, R. Phonon dispersion and Raman scattering in hexagonal GaN and AlN. Phys. Rev. B. 1998, 58, 12899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Heuseen, K.; Hashim, M.R.; Ali, N.K. Effect of different electrolytes on porous GaN using photo-electrochemical etching. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 6197–6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ning, J.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y.; Yan, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, D. Raman analysis of E2 (High) and A1 (LO) phonon to the stress-free GaN grown on sputtered AlN/Graphene buffer layer. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, C.; Bouzidi, C.; Elhouichet, H.; Gelloz, B.; Ferid, M. Mg doping induced high structural quality of sol–gel ZnO nanocrystals: Application in photocatalysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 349, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.M.; Saleh, W.R.; Al-Sammarraie, A.M.A. Structural and optical properties of ZnO nanostructures synthesized by hydrothermal method at different conditions. Nano Hybrids and Composites, 2022, 35, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Kumar, S.; Arshi, N.; Anwar, M.S.; Koo, B.H. Morphological evolution between nanorods to nanosheets and room temperature ferromagnetism of Fe-doped ZnO nanostructures. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2012, 14, 4016–4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.-L.; Su, Y.-K.; Ma, C.-Y. Nitrogen-doped p-type ZnO films prepared from nitrogen gas radio-frequency magnetron sputtering. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 053705–053708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qin, J.; Xue, Y.; Yu, P.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Liu, R. Effect of aspect ratio and surface defects on the photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanorods. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siva, N.; Sakthi, D.; Ragupathy, S.; Arun, V.; Kannadasan, N. Synthesis, structural, optical and photocatalytic behavior of Sn doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2020, 253, 114497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Kumar, A. Infrared Lattice Vibrations of Nitrogen-doped ZnO Thin Films. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2007, 1035, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decremps, F.; Datchi, F.; Saitta, A.M.; Polian, A.; Pascarelli, S.; Di Cicco, A.; Baudelet, F. Local structure of condensed zinc oxide. Phys. Rev. B. 2003, 68, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Song, A.; Park, Y.J.; Seo, J.H.; Walker, B.; Chung, K.-B. Tungsten-doped zinc oxide and indium–zinc oxide films as high-performance electron-transport layers in N–I–P perovskite solar cells. Polymers, 2020, 12, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.; Tsai, C.-L.; Petrov, S.; Marinova, V.; Petrova, D.; Napoleonov, B.; Blagoev, B.; Strijkova, V.; Hsu, K.Y.; Lin, S.H. Atomic layer-deposited Al-doped ZnO thin films for display applications. Coatings 2020, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.D.C.; Veal, T.D.; Fuchs, F.; Wang, C.Y.; Payne, D.J.; Bourlange, A.; Zhang, H.; Bell, G.R.; Cimalla, V.; Ambacher, O.; Egdell, R.G.; Bechstedt, F.; McConville, C.F. Band gap, electronic structure, and surface electron accumulation of cubic and rhombohedral In2O3. Phys. Rev. B. 2009, 79, 205211–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pauw, L.J. A method of measuring specific resistivity and Hall effect of discs of arbitrary shape. Philips Res. Rep. 1958, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Imasato, K.; Kang, S.D.; Ohno, S.; Snyder, G.J. Band engineering in Mg3Sb2 by alloying with Mg3Bi2 for enhanced thermoelectric performance. Mater. Horiz. 2018, 5, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keavney, D.J.; Buchholz, D.B.; Ma, Q.; Chang, R.P.H. Where does the spin reside in ferromagnetic Cu-doped ZnO? Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 012501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhart, P.; Albe, K.; Klein, A. First-principles study of intrinsic point defects in ZnO: Role of band structure, volume relaxation, and finite-size effects. Phys. Rev. B. 2006, 73, 205203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.B.; Wei, S.H.; Zunger, A. Microscopic Origin of the Phenomenological Equilibrium “Doping Limit Rule” in n-Type III-V Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 1232–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Y.; Mal'shukov, A.G.; Chu, C.S. Nonuniversality of the intrinsic inverse spin-Hall effect in diffusive systems. Phys. Rev. B. 2012, 85, 165201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Growth Parameters | Experimental values |

|---|---|

| Substrate | Unintentionally doped GaN (n-type) |

| Metal oxide target | ZnO ceramic (99.999%) |

| Base Pressure | 3.0 x 10-5 milli bar |

| Working Pressure | 2.0 x 10-2 milli bar |

| Substrate Temperature | Room temperature (no intentional substrate heating ) |

| Argon gas (atmosphere) | 10 sccm |

| Nitrogen gas (doping) | 2 sccm, 4 sccm, 6 sccm, 8 sccm and 10 sccm respectively. |

| Radio frequency (RF) sputtering power | 150 W |

| Film Sample | Nitogen gas flow (sccm) | RMS values on non-porous GaN (nm) | RMS values on etched porous GaN (nm) | Carrier concentraion (cm−3) | Carrier mobility (cm2V−1s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure ZnO | 0 sccm | 11.2 | 3.4 | 4.71 × 1017 | 13.15 |

| N-doped ZnO | 2 sccm | - | 2.1 | 2.12 x 1018 | 2.5 |

| N-doped ZnO | 4 sccm | - | 2.0 | 8.54 x 1019 | 37.5 |

| N-doped ZnO | 6 sccm | - | 1.7 | 4.40 x 1021 | 1.0 |

| N-doped ZnO | 8 sccm | - | 1.6 | 5.29 x 1021 | 1.7 |

| N-doped ZnO | 10 sccm | - | 1.1 | 7.99 x 1018 | 29.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).