Introduction:

Menopause marks the end of the reproductive life cycle for women, non-binary individuals, and transgender men. While many experience natural menopause over time, others may undergo it due to medical conditions or treatments like radical hysterectomy or long-term medications. Natural menopause progresses gradually with perimenopause, whereas surgical or medical menopause is sudden and often presents severe symptoms immediately (1).

Each year, about 25 million women enter menopause, a number expected to rise as the global population ages. By 2030, approximately 1.2 billion women will be menopausal or perimenopausal, mainly due to increased life expectancy. This demographic shift highlights the need to address the health and well-being of menopausal women, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where menopause often occurs earlier—between ages 45 and 50—compared to high-income countries (HICs), where the average onset is around 51. In LMICs, factors like malnutrition and infectious diseases contribute to this earlier transition, leading to significant health and socioeconomic impacts. Access to healthcare for managing menopausal symptoms in these regions is limited, often exacerbated by underreporting of the issue. Conversely, women in HICs benefit from better healthcare access and treatment options, though disparities still exist within specific populations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is the main treatment for menopausal symptoms and may lower the risk of cardiovascular issues [

2] and osteoporosis. HRT is also beneficial after surgical menopause to restore hormone levels [

4]. Testosterone can enhance libido, energy, mood, and overall well-being by addressing declines in androgen production [

7]. However, awareness of menopause-related cardiovascular risks is low, with only 56% of women informed. Menopause changes hormones, body fat distribution, lipids, and vascular health, increasing cardiovascular risk, particularly after bilateral oophorectomy [

1].

HRT is offered in two main forms: oestrogen alone or in combination with progesterone, and it is available in oral and transdermal formulations. However, access to HRT and gynaecological services can vary significantly, even within individual countries. For example, a study in the UK revealed an 18% lower rate of HRT prescribing in the most deprived areas (9), showing a preference for oral HRT over transdermal options despite the latter having a reduced cardiovascular risk. These disparities underscore the difficulty in generalising findings to LMICs, where healthcare access is often limited. Economic evaluations in LMICs need more comprehensive data on treatment preferences, health outcomes, and associated costs. Funding limitations for women’s health equally pose significant challenges.

To better understand health outcomes, and develop evidence-based tools, we developed the MARIE project which includes a multi-step health economics work-stream to report the economic impact of menopause across the MARIE consortium countries.

Methods:

We used an cross-sectional exploratory design in the first instance to gain initial insights as part of a pilot study to understand the economic barriers and impact, disparities related to accessing HRT and the implications to the female workforce, and affordability costs of menopause. Women are a significant part of the informal economy, facing physically demanding labour and lacking health support. Unmanaged menopausal symptoms can lead to productivity loss, affecting individuals, families, and national economies. This study aims to address complex issues related to HRT and menopause in LMICs, where comprehensive data is scarce, by gathering baseline insights and uncovering trends.

The primary aim of this pilot study is to explore and understand economic barriers and disparities related to accessing HRT by examining their availability, cost, and impact on women in the workforce. The secondary aim is to report insights into future economic challenges for the regions based on female workforce data to inform future policies and lay the groundwork for comprehensive insights for healthcare services, professionals, and researchers.

Data Sources and Collection

Data on female workforce participation were sourced from Our World in Data (OWiD) [

8], focusing on trends in participation, gender differences, and unemployment. A dashboard visualised female workforce participation by country.

MARIE project investigators collected data on the availability and pricing of HRTs from Brazil, Ghana, Malaysia, Nepal, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka. The selection of the country was based on the convenience of researchers and the planned future study aims to include more countries than the currently selected ones. They used local pharmacy price lists, collaborated with pharmacists, and accessed national healthcare databases. This included information on HRT medicines, formulations (oral, transdermal, gels), and surgical procedures related to menopause.

Cost Analysis and Affordability Measure

The affordability of HRT medicines is crucial for understanding economic disparities. It was measured by the number of days of minimum wage required to buy a two-month supply of HRT, providing a clear, comparable metric for assessing financial burden. Many women in LMICs pay out-of-pocket for healthcare, making direct cost comparisons insufficient. By framing affordability in terms of workdays needed, we offer a tangible measure of financial strain.

Additionally, we collected Gross National Income (GNI) per capita data from World Bank reports to contextualize these affordability findings. GNI per capita serves as a macroeconomic indicator of a country’s wealth, and when combined with minimum wage data, it clarifies how income levels impact healthcare accessibility. Among the studied countries, Brazil and Malaysia are Upper-Middle-Income countries, while the others are LMICs. This dual measure enables a standardized comparison across countries with varying economic conditions. Furthermore, menopausal women in these settings often balance paid work with unpaid caregiving responsibilities, amplifying both financial and physical burdens. GNI per capita [

9] and minimum wage per day [

10] for each country are provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of interest was the female workforce availability, cost, and affordability of HRT medicines alongside several secondary outcomes, as described below;

Female labour force participation in the selected countries

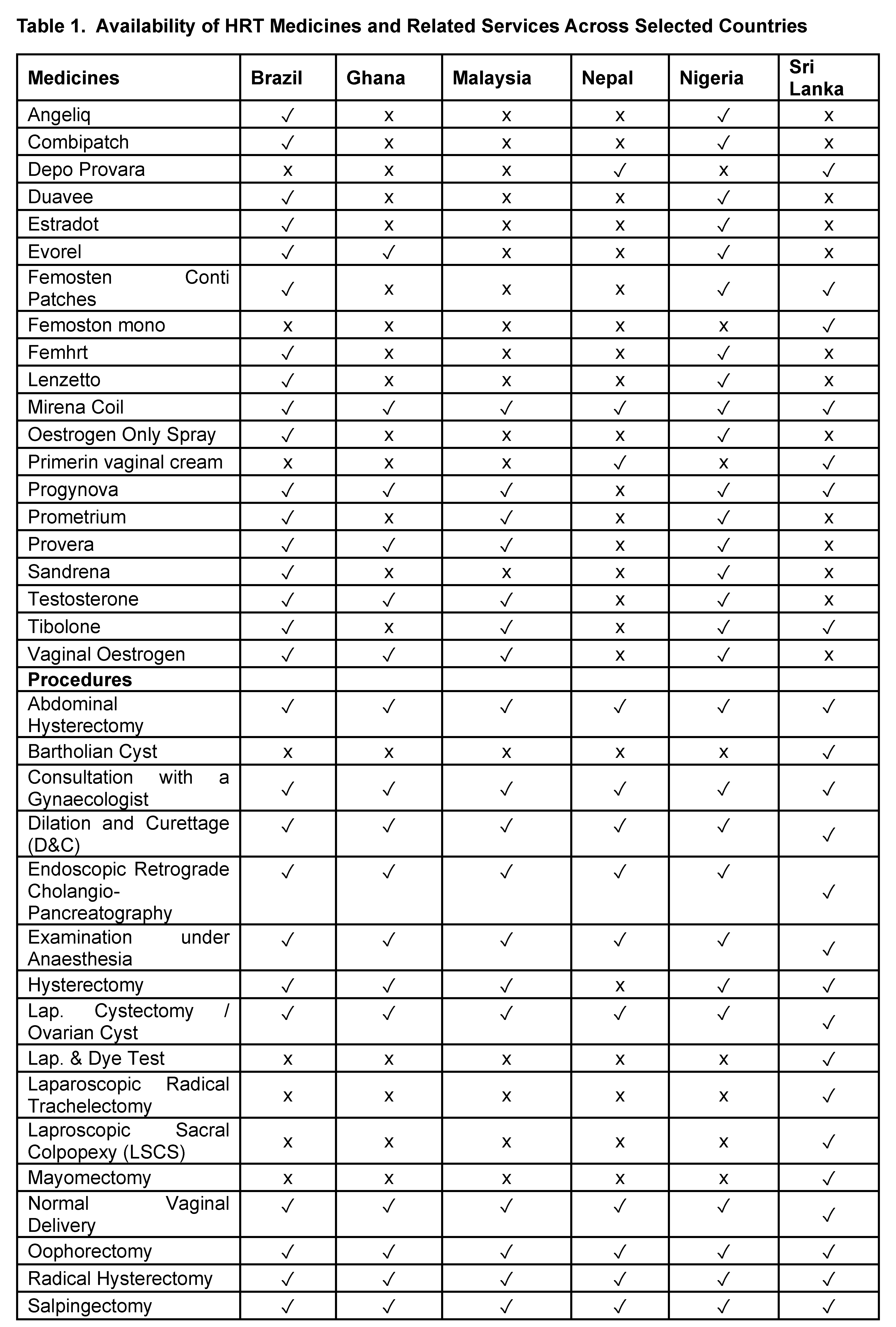

Availability of HRT medicines and menopause-related gynaecological and surgical services by assessing the number and type of HRT medicines and services available in each country. The list of medicines and services was initially developed by consultation among the MARIE project members.

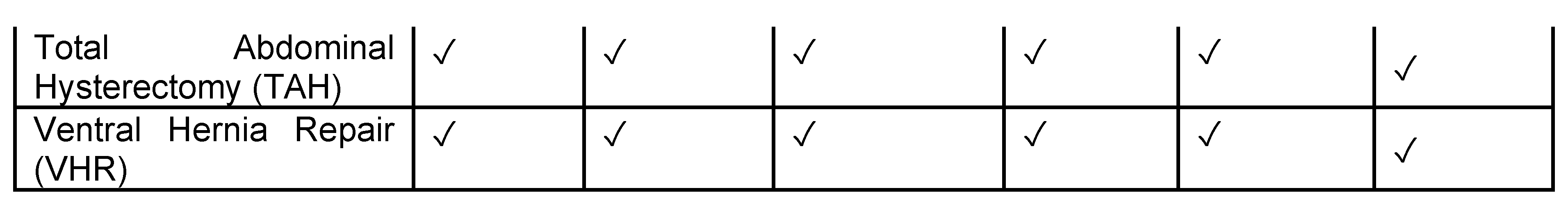

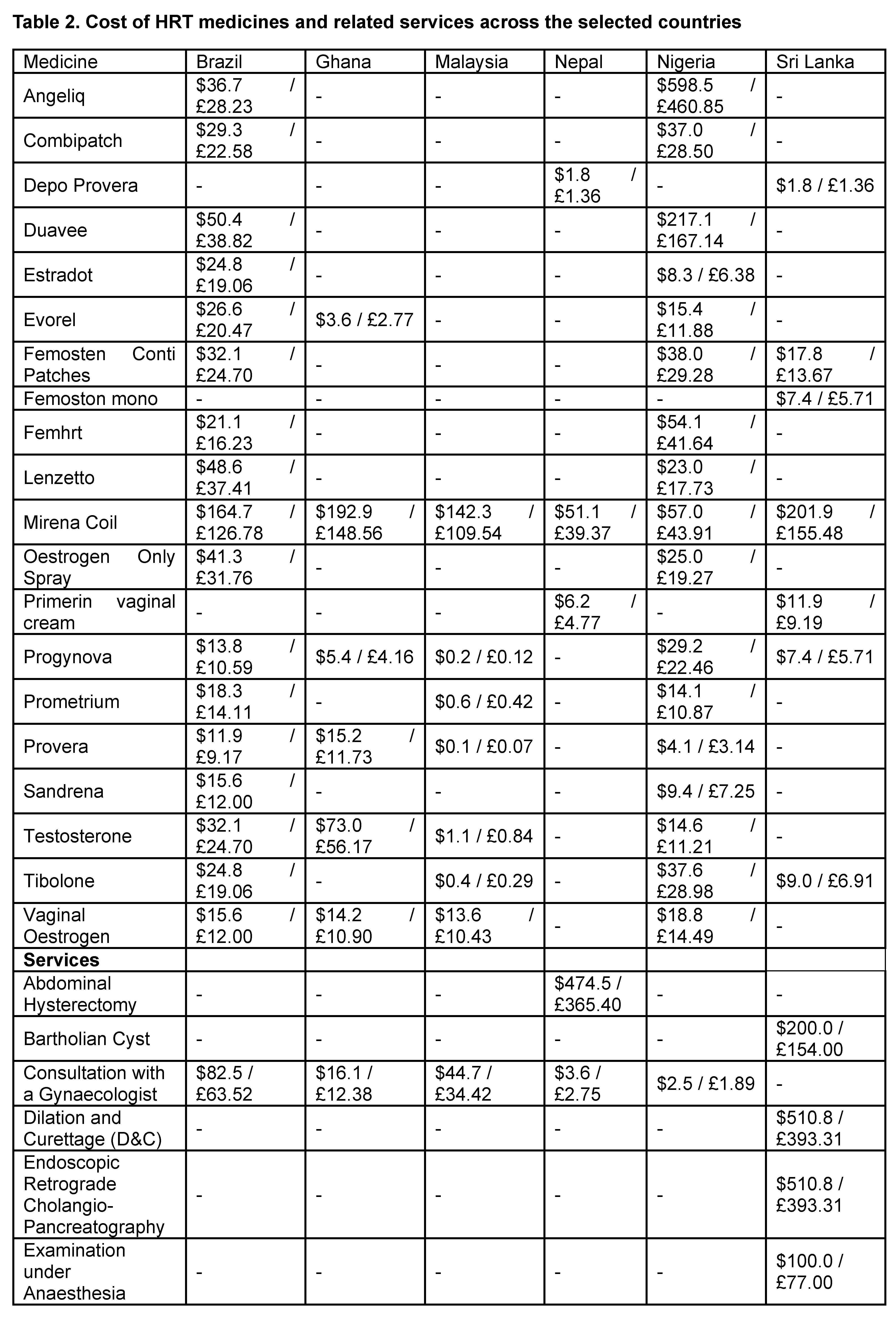

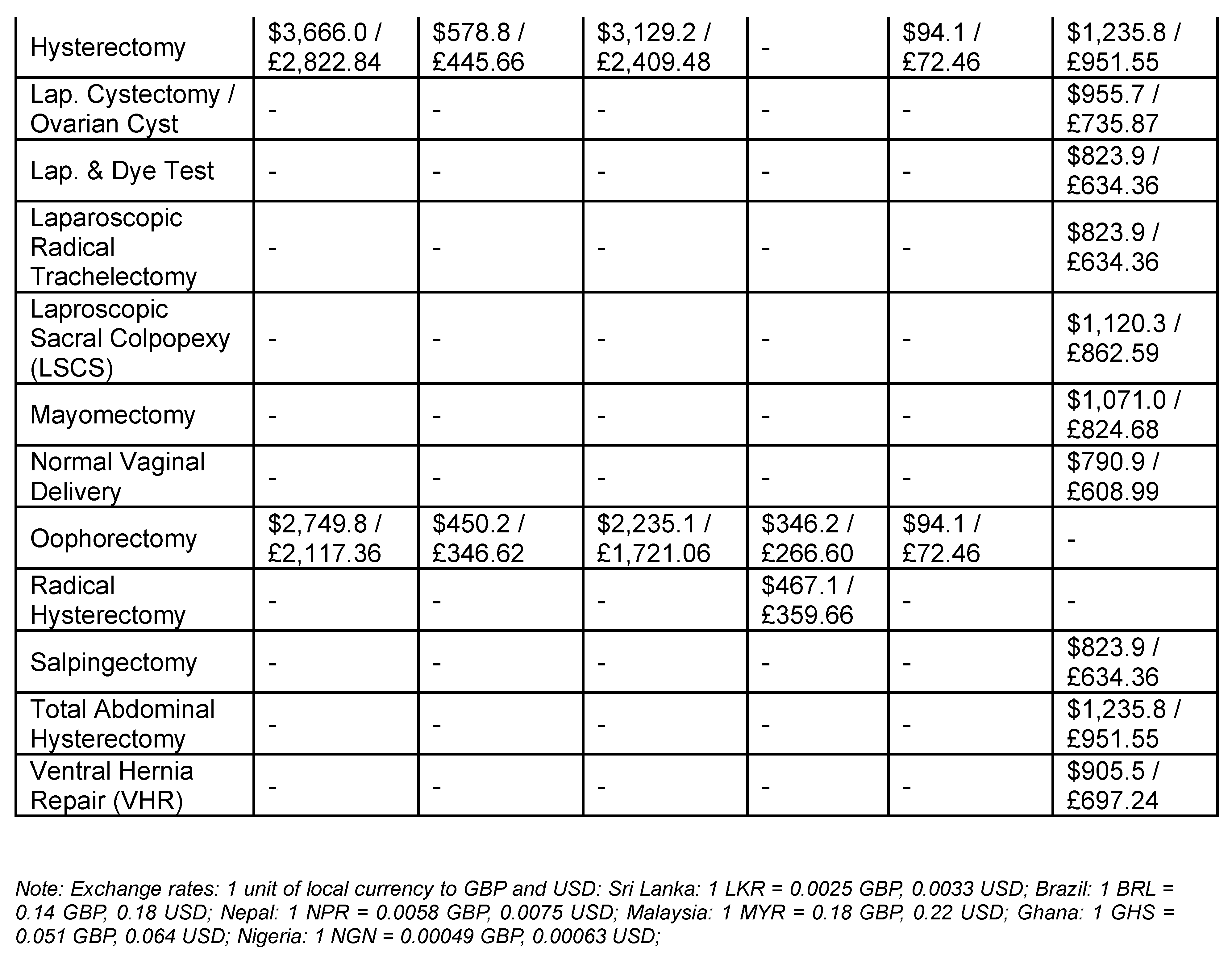

The cost of HRTs and menopause-related gynaecological and surgical services were calculated as the price of individual medicines and services, which were collected in local currencies and converted to USD for standardisation.

The affordability of HRTs and menopause-related gynaecological and surgical services is calculated by dividing each prescription's price (usually for two months) by the daily minimum wage in each country and the annual supply of medicines GNI per capita income.

Some of the items reported in the study may not be directly classified as the HRT treatment, for example, Mirena, primarily used for contraception and treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding, was included in our analysis due to its off-label use in managing menopausal symptoms. Similarly, surgical procedures included in the analysis were selected based on their potential association with menopause-related health conditions, such as gynaecological visit, hysterectomy, ovarian surgeries and other services named in the services list.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed descriptively, measuring affordability as the minimum wage days needed to buy a two-month HRT prescription. A comparison of six countries highlighted availability, pricing, and affordability variations. Higher-income countries like Brazil and Malaysia were contrasted with lower-income countries such as Ghana and Nepal to assess the financial accessibility of HRT in different economic contexts. The data facilitated a comparison of available medicines and costs in each country.

Ethical Considerations

This study did not involve human subjects or personal health data, so no ethical approval was needed. All data used were from publicly available sources or established local databases.

Results:

Understanding HRT involves considering its availability, cost, and economic impact on workforce productivity. For migrant populations, while these factors may not pose issues in HICs, their perceptions and attitudes towards HRT can be influenced by their home country’s healthcare system.

Female Labour Force Participation

Supplementary Figure S1 highlights female labour force participation and gender equality worldwide. The top left map shows countries where women have equal job access without spousal permission. In the 2015 bubble chart, older women (45-54) generally participate more in the workforce than younger women (25-34), with Nepal having the highest rate for both age groups. The 2022 bar chart shows Ghana leading female participation at 65% and Nepal at 28%, with Brazil and Nigeria at 54% and 52%. The line graph (1991–2022) reveals stable participation in Brazil and Ghana but a decline in Sri Lanka. The 2022 unemployment map shows Brazil’s low rate (4%) amid higher rates elsewhere.

Cost of HRT Medicines and Related Services Across Selected Countries

The data shows significant cost disparities between HRT medicines and menopause-related gynaecological services across Brazil, Ghana, Malaysia, Nepal, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka. Brazil offers a broad range of HRT options at moderate prices, like Angeliq at $36.7 (£28.23), while Nigeria, despite wide availability, shows high prices, with Angeliq at $598.5 (£460.85). The Mirena Coil ranges from $51.1 (£39.37) in Nepal to $201.9 (£155.48) in Sri Lanka. Malaysia and Ghana offer lower prices for some medicines, such as Progynova at $0.2 (£0.12) in Malaysia compared to $29.2 (£22.46) in Nigeria.

Menopause-related service costs also vary widely: an abdominal hysterectomy is $474.5 (£365.40) in Nepal and $1,235.8 (£951.55) in Sri Lanka, with basic consultations cheaper in Ghana ($16.1 / £12.38) and Nepal ($3.6 / £2.75) than in Brazil ($82.5 / £63.52). Advanced procedures like Sri Lanka’s laparoscopic cystectomy cost $955.7 (£735.87), highlighting limited access and high costs for complex care in low-resource areas. Further details are provided in Table 2.

Affordability of HRT Across Different Countries

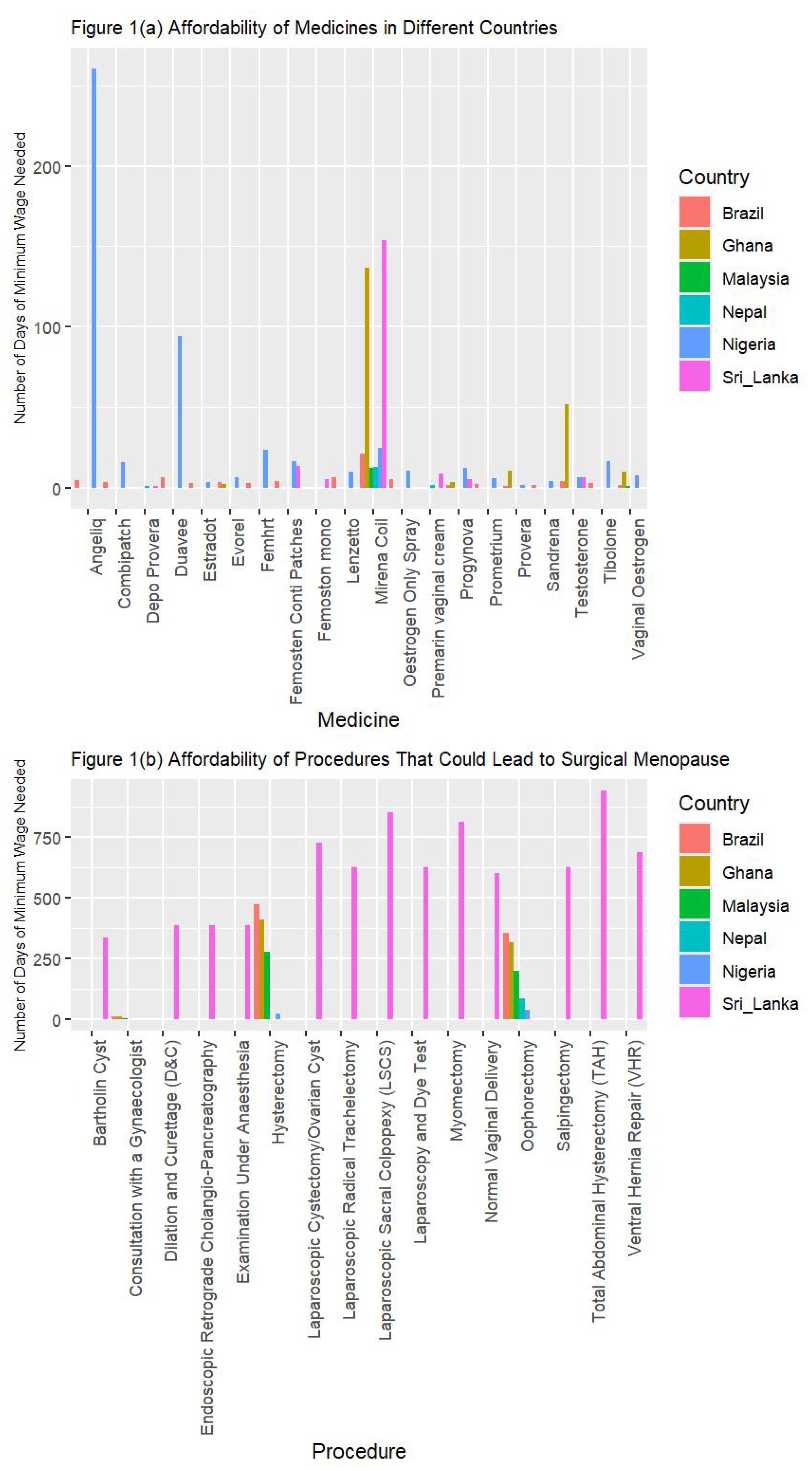

Figure 1 highlights the major disparities in the affordability of HRT medicines and menopause-related procedures across LMICs, measured in days of minimum-wage work. For medicines (Figure 1a), costs vary widely: Brazil’s Mirena Coil requires 21.31 days of wages, while Malaysia’s Progynova costs only 0.01 day, though the Mirena Coil is 12.69 days. In Nepal, Depo Provera is affordable at 1.34 days’ wages, whereas Nigeria faces severe affordability issues, with Angeliq priced at 260.07 days’ wages and Sri Lanka’s Mirena Coil at 153.54 days.

For procedures (Figure 1b), Sri Lanka generally requires fewer workdays. Basic gynaecologist consultations take less than two days of work in all countries, with Nepal at just 0.8 days. Complex surgeries, such as laparoscopic trachelectomy in Sri Lanka, cost up to 48 days’ wages, while abdominal hysterectomies in Nepal range from 20 to 40 days. Brazil, Ghana, and Nigeria face higher wage burdens for surgeries like hysterectomies, requiring 34–40 days.

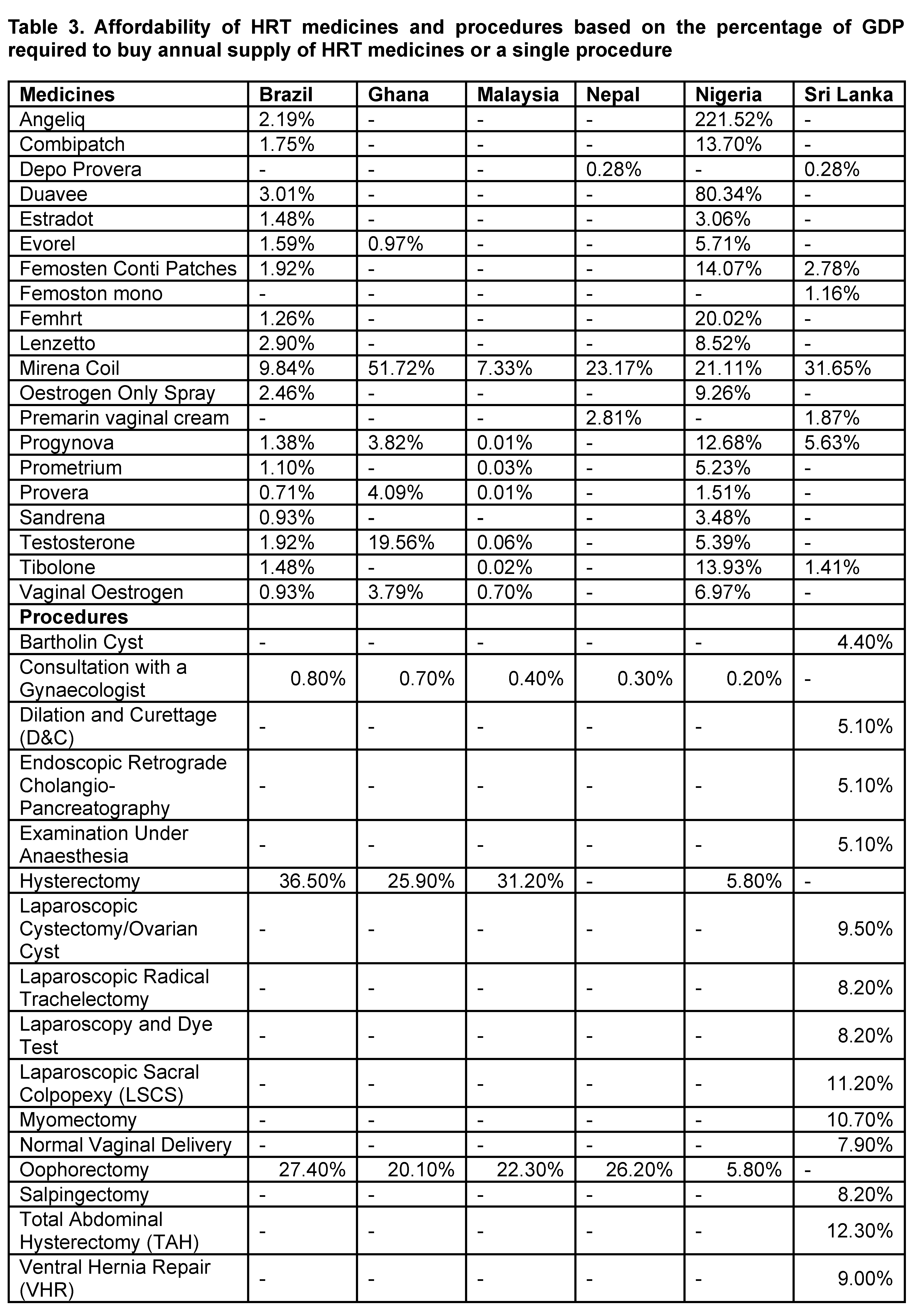

Affordability by income also varies between the countries (Table 3). Brazil’s Mirena Coil consumes 9.84% of annual income, Ghana’s reaches 51.72%, and Malaysia offers low-cost options like Progynova at 0.01%. Nigeria struggles with extreme costs, where Angeliq is 221.52% of annual income. Basic consultations are affordable across all countries for procedures, while major surgeries cost up to 2% of income in Brazil and Nepal, posing significant financial challenges. Sri Lanka offers the lowest costs for basic and advanced surgical care, while higher costs in Brazil, Ghana, and Nigeria indicate considerable financial barriers to complex care.

Discussion:

Our study reveals significant disparities in the availability, cost, and affordability of HRT medicines and gynaecological procedures, limiting access to affordable menopause care and negatively impacting women's health. With women making up a large portion of the workforce in many LMICs, high out-of-pocket healthcare costs and limited access lead to untreated health issues, reducing labour productivity and efficiency.

Women in LMICs face high costs for HRT and essential gynaecological procedures, such as screenings for menopause-related risks like osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Williams et al. (2008) indicate that HRT is often unavailable or unaffordable, resulting in untreated symptoms. In contrast, high-income countries offer better access through subsidies and insurance, enabling consistent care [

5,

11]. Limited healthcare infrastructure in LMICs further restricts access to quality menopausal care, as highlighted by the UN Population Fund and HelpAge International (2012), which note a shortage of facilities, trained providers, and medical supplies.[

4] The high cost of HRT limits access for many women in LMICs, widening health disparities compared to HICs. While Brazil and Nigeria offer a greater variety of HRT options, prices remain unaffordable; in Nigeria, Angeliq costs

$598.51 (£460.58), equating to over 221.52% of income, while in Brazil, the Mirena coil costs

$164.65 (£123.60), or 9.84% of income. Surgical procedures such as hysterectomies are often out of reach financially, especially in rural areas. Ghana has only six available HRT options, while Nepal offers just three. Some medicines, like Depo-Provera in Nepal, are more affordable at

$1.76 (0.28% of income), but overall choices remain limited. Malaysia and Sri Lanka have mid-range pricing, yet the high cost of treatments like the Mirena coil—7.33% of income in Malaysia and 31.65% in Sri Lanka—makes access to advanced procedures, such as laparoscopic surgeries, difficult.

The significant proportion of healthcare costs relative to income highlights broader economic challenges, including GDP, health spending, and productivity. Countries with higher GDP, such as Brazil, tend to invest more in public healthcare, which helps lower out-of-pocket expenses. In contrast, Nigeria and Brazil struggle with high HRT costs due to limited health funding. Nigeria allocates only 3.6% of its GDP to healthcare, compared to Brazil’s 9.2%, leading to potentially an affordability challenges. When treatment costs exceed 200% of monthly income in Nigeria, it severely limits women’s access to care and impacts workforce participation.

Most hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and procedural costs in LMICs are paid out-of-pocket due to limited insurance coverage and government subsidies, disproportionately affecting lower-income families [

12]. High costs force many women to forgo treatment for symptoms like hot flushes and fatigue, impacting their productivity. For example, in Brazil, the Mirena Coil costs nearly 10% of a woman's income, with regional disparities further limiting access. In Sri Lanka, even more affordable procedures may still be hard for low-income women to access. Increasing local production of affordable generic HRT and improving distribution in underserved areas could enhance accessibility. Additionally, rural women face travel costs and lost work hours to access care, worsening economic disparities. Strengthening rural healthcare in LMICs could reduce treatment access time and support workforce stability, boosting national productivity.

Comparison to High-Income Countries (HICs)

Our findings highlight that HRT guidelines from HICs, such as the British Menopause Society (BMS), do not adequately address the realities faced in LMICs or their immigrant populations. The BMS guidelines are tailored to resource-rich environments, primarily for Caucasian women, with healthcare infrastructure that supports regular consultations and personalised dosage adjustments [

13]. In the UK, HRT packaging varies significantly, with prescriptions determined case-by-case by the physician based on patient needs and responses to treatment [

14]. Patients also have options for private HRT treatments, such as testosterone therapy, that are not typically available through the NHS. In contrast, LMICs face significant resource limitations and cost barriers. Additionally, options like private testosterone therapy in the UK are not readily available in LMICs.

Migration from LMICs to HICs presents both opportunities and challenges for accessing HRT. While migrants find more options in HICs, they often encounter healthcare systems that may not fully meet their needs. In the UK, HRT is free in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and in England, it costs £19.30 per year under a Prescription Prepayment Certificate, although additional treatments require a separate certificate [

15]. Culturally competent healthcare in HICs can provide tailored education to help migrants navigate the system and make informed decisions, potentially reducing care discontinuation due to misunderstandings.

Significant variation in HRT access exists within the UK, particularly among deprived and ethnic minority populations, a challenge even more pronounced in LMICs. Funders often reduce deprivation to economic issues, but our findings show that barriers to HRT in these regions extend beyond income level [

16]. Despite many educated women in LMICs, HRT use remains low due to limited availability, high costs, and varied pricing, highlighting the need for a nuanced understanding of HRT accessibility.

Socioeconomic and Cultural Implications

Labour force participation among women is higher in HICs like Australia and Scandinavia, thanks to better access to education, economic opportunities, and supportive policies such as paid family leave and childcare [

17]. These measures help women remain in the workforce and boost national economic productivity. In contrast, LMICs face barriers such as limited education, cultural constraints, and fewer economic resources, which result in lower female participation in the workforce [

18,

19] In HICs, women typically retire around 65 due to supportive retirement policies, while in LMICs, they often retire earlier due to economic necessity and job demands [

18,

19]. Untreated menopausal symptoms—such as hot flushes, depression, and anxiety—can lead to social isolation and reduced productivity, negatively affecting family and community involvement [

18,

19].

Untreated menopause raises the risk of long-term health issues like cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis, straining healthcare systems. The economic impact includes high absenteeism, decreased efficiency, and early retirement, leading to significant losses. Investing in menopausal care, such as HRT and gynaecological services, offers a strong return on investment, enhancing workforce productivity, reducing absenteeism, and supporting gender equality in leadership roles [

18,

19].

Australia’s dedicated funding for women’s health, particularly in menopause research, illustrates how targeted investments can improve health outcomes and workforce participation [

20]. Similar funding models in LMICs through subsidies, local HRT production, and awareness campaigns could enhance health outcomes and economic resilience [

18]. Investing in menopausal care in LMICs may yield even greater returns by preventing economic losses from untreated symptoms, thus improving workforce productivity and reducing long-term healthcare costs. Investing in this area is a beneficial economic strategy that supports individual health and national growth [

18,

19].

Practical Implication

Disparities in the affordability of HRT medications hinder access to menopausal care and impact female labor force participation (FLFP) and socioeconomic outcomes. The U-shaped curve of FLFP in relation to economic development, as noted by Goldin (1995) [

21] and Jayachandran (2022) [

22], shows that initial economic advancement can reduce FLFP due to limited formal job opportunities and societal barriers, before stabilizing with increased employment and educational opportunities for women.

In LMICs, women's labour participation is mainly driven by economic necessity, compounded by restricted access to affordable healthcare. While menopausal symptoms can impact work performance, the direct link between HRT access and workforce participation remains understudied and requires further research. Additionally, unmanaged menopausal symptoms may contribute to productivity loss, but comparative analyses with other health burdens, such as untreated iron deficiency anemia (IDA), are necessary to establish priorities in resource-limited settings. Sub-Saharan Africa shows high female labour force participation as a survival strategy, while HICs like Norway and Sweden offer policies that support career advancement and family life. Hence, such studies are important.

In LMICs, insufficient policy support, high costs, and limited HRT availability exacerbate health and social inequalities. Untreated menopausal symptoms can negatively affect productivity and economic growth. While younger women increasingly participate in the workforce due to recent reforms, older women face higher dropout rates driven by societal expectations and restricted healthcare access. To address these challenges, governments should implement healthcare reforms that lower the cost of essential HRT treatments and menopause-related procedures through direct subsidies and price regulations in public healthcare. Improving access to HRT and menopause care may increase utilisation, helping to reduce health and social inequalities, enhance workforce participation among older women, and contribute to overall economic growth. Public health campaigns can help raise awareness about menopause and normalise discussions on HRT, reducing stigma and encouraging women to seek care [

23]. Training healthcare providers in underserved areas to manage menopausal symptoms and provide accurate HRT information is crucial [

24,

25,

26]. Pharmaceutical companies should focus on producing affordable generic HRT options. Policy interventions should prioritise affordable HRT access, educational programs on its benefits, and gender-equitable employment policies. Enhancing healthcare access could support women’s well-being and economic development. Future research should explore the long-term health impacts of limited HRT access and the influence of cultural factors on menopause-related care.

Addressing knowledge gaps in menopausal healthcare in LMICs requires dedicated funding and focused research. Menopause significantly impacts women’s health, yet research remains underfunded. Investing in affordable HRT R&D is essential for ethical reasons and potential economic gains, as improved health can enhance productivity and reduce healthcare costs. Future funding should prioritize local HRT production, healthcare financing policy analyses, and evaluations of the economic benefits of menopausal care. Expanding HRT access would promote healthier ageing, support workforce continuity, and drive economic growth, highlighting the need to invest in women’s health.

Strengths and Limitations

This study's broad geographical scope enables comparisons across six LMICs, shedding light on global disparities in HRT access. By assessing affordability in terms of minimum wage days for purchasing HRT or covering procedural costs, it reveals the financial burden on poorer households. Additionally, measuring affordability against GNI per capita provides insight into average household access, highlighting economic barriers to essential services in LMICs.

This study has limitations, primarily focusing on the economic aspects of HRT access without examining health outcomes of untreated menopause. Future research should explore specific health risks, such as increased cardiovascular disease and reduced life expectancy, associated with limited HRT access. Additionally, data on availability and pricing were sourced from select areas, potentially overlooking challenges in rural regions. Cultural factors, including stigma and lack of awareness, also influence women's decisions to seek HRT [

25,

27,

28] and need further investigation to fully understand the barriers to access.

Conclusions:

This study emphasizes the need for equitable access to HRT medicines and services in LMICs, highlighting significant gaps in availability and affordability. Women in certain regions face barriers to necessary care, which can hinder their career advancement and long-term employment. These challenges impact the female workforce and limit economic potential, as their participation is crucial for GDP growth. Enhancing access to affordable HRT can reduce the health burden of menopause, leading to improved well-being and productivity. Policy changes and efforts from manufacturers to lower costs are essential, along with more research to fully understand and address these disparities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

GD conceptualised the MARIE project as part of the ELEMI program. GD conceptualised the economic analysis with SK. First draft was written by SG and furthered by SK and GD. Data collection was completed by SG, TM, VP, TTH, CLBP, IA, GUE and FK. SG conducted the analysis. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

NIHR Research Capability Funding.

Availability of data and material

The data shared within this manuscript is available within government organisations’ and their ministries or department’s of health and in public reports.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

Code availability

Not applicable

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

No participants were involved within this paper

Consent for publication

All authors consented to publish this manuscript

References

- Yengo L, Vedantam S, Marouli E, Sidorenko J, Bartell E, Sakaue S, et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature. 2022;610(7933):704-12.

- Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, Bromberger JT, Everson-Rose SA, Gold EB, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(4):531-9.

- Whiteley J, Wagner J-S, Bushmakin A, Kopenhafer L, DiBonaventura M, Racketa J. Impact of the severity of vasomotor symptoms on health status, resource use, and productivity. Menopause. 2013;20(5):518-24.

- Challenge, A. Ageing in the Twenty-First Century.

- Shifren JL, Gass ML, Group NRfCCoMWW. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1038-62.

- World Health Organization. Menopause 2024 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/menopause.

- Davis SR, Baber R, Panay N, Bitzer J, Perez SC, Islam RM, et al. Global consensus position statement on the use of testosterone therapy for women. The journal of sexual medicine. 2019;16(9):1331-7.

- Roser M. OWID Homepage. Our World in Data. 2024.

- World Bank Group. GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) - East Asia & Pacific, [Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?locations=Z4.

- Trading Economics. Minimum Wages | Asia, [Available from: https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/minimum-wages?continent=asia.

- Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, Lewis J, Clark RV. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62(2):153-9.

- Tabuzo MMB, Hernandez MALU, Chua AE, Maningat PD, Chiu HHC, Jamora RDG. Pituitary Adenoma in the Philippines: A Scoping Review on the Treatment Gaps, Challenges, and Current State of Care. Medical Sciences. 2024;12(1):16.

- Hamoda H, Panay N, Arya R, Savvas M, Society BM, Concern WsH. The British Menopause Society & Women’s Health Concern 2016 recommendations on hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women. Post Reproductive Health. 2016;22(4):165-83.

- Townsend, J. Hormone replacement therapy: assessment of present use, costs, and trends. British journal of general practice. 1998;48(427):955-8.

- Department of Health & Social Care (UK). New scheme for cheaper hormone replacement therapy launches London, United Kingdom: Department of Health and Social Care (UK); 2023 [Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-scheme-for-cheaper-hormone-replacement-therapy-launches.

- Jaff, N. Does one size fit all? The usefulness of menopause education across low and middle income countries. Maturitas. 2023;173:38.

- Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (KPMG). When will I retire? Sydney, Australia: KPMG; 2022.

- Dvorkin MA, Shell H. A cross-country comparison of labor force participation. Economic Synopses. 2015(17).

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2023. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum; 2023 June 2023.

- Williamson, J. Menopause: The silent economic crisis2023. Available from: https://www.financialstandard.com.au/news/menopause-the-silent-economic-crisis-179798921.

- Goldin, C. The U-shaped female labor force function in economic development and economic history. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, Mass., USA; 1994.

- Jayachandran, S. How economic development influences the environment. Annual Review of Economics. 2022;14(1):229-52.

- Hunter MS, O'Dea I, Britten N. Decision-making and hormone replacement therapy: a qualitative analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(10):1541-8.

- Ma J, Drieling R, Stafford RS. US women desire greater professional guidance on hormone and alternative therapies for menopause symptom management. Menopause. 2006;13(3):506-16.

- Koysombat K, Mukherjee A, Nyunt S, Pedder H, Vinogradova Y, Burgin J, et al. Factors affecting shared decision-making concerning menopausal hormone therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2024;1538(1):34-44.

- Palacios S, Stevenson JC, Schaudig K, Lukasiewicz M, Graziottin A. Hormone therapy for first-line management of menopausal symptoms: Practical recommendations. Women's Health. 2019;15:1745506519864009.

- Griffiths, F. Women's control and choice regarding HRT. Social science & medicine. 1999;49(4):469-82.

- Griffiths, F. Women's decisions about whether or not to take hormone replacement therapy: influence of social and medical factors. British Journal of General Practice. 1995;45(398):477-80.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).