1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has starkly highlighted the critical need for innovative and scalable disinfection technologies to mitigate the transmission of infectious diseases through contaminated surfaces and air. Current gold standard disinfection methods often rely on energy-intensive and chemically intensive processes, raising concerns about environmental sustainability and potential long-term health impacts. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), particularly photocatalysis, have emerged as a promising alternative for disinfection. Photocatalysis leverages reactive oxygen species (ROS) to disrupt viral capsids and render pathogens noninfectious. However, several critical knowledge gaps impede the widespread adoption of this technology. A more comprehensive understanding of the photoinactivation mechanisms of viruses, including their rapid mutagenicity and post-treatment viability, is essential for optimising photocatalytic disinfection protocols. While photocatalytic oxidation [

1,

2] offers an attractive solution for air purification by effectively decomposing diverse air pollutants into non-toxic byproducts, translating this technology into commercially viable photocatalytic reactors presents significant engineering challenges. The development of a robust, scalable, and efficient method for immobilizing the photocatalyst onto a suitable support material remains the primary obstacle. Achieving successful and durable immobilisation under ambient conditions would represent a significant advance, accelerating the commercialization and deployment of photocatalytic disinfection technologies for both surface and air decontamination. Although photocatalytic air purification offers numerous advantages, its practical application is often hampered by limitations, such as a relatively slow purification rate. Combining photocatalysis with complementary technologies, such as adsorption, photothermal catalysis (PTC), or plasma catalysis, presents a promising avenue for synergistic enhancement. Such hybrid approaches can improve overall treatment performance by, for example, facilitating the rapid capture of target compounds on the catalyst surface. PTC, in particular, combines the high efficiency and durability of thermal catalytic oxidation with the benefit of a lower energy consumption. Similarly, integrating plasma treatment can promote the degradation of air pollutants, while photocatalysis minimises the formation of potentially harmful byproducts. Despite these potential benefits, hybrid processes remain in their early stages of development [

3,

4], necessitating further in-depth research to fully elucidate the underlying synergistic mechanisms and address the practical engineering challenges associated with their implementation. Hybrid technologies offer a promising approach for integration within heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems to significantly mitigate the spread of viral infections, pathogenic microflora and molecular air pollutants [

5,

6,

7].

Public and administrative buildings commonly use supply and exhaust HVAC systems, often incorporating mechanical ventilation with coarse filters and rotary heat recovery devices. Although the main function of these HVAC systems is to maintain the indoor microclimate parameters within defined specifications [

8,

9,

10], under certain operating conditions, they can inadvertently act as reservoirs and vectors for the accumulation and dissemination of airborne pollutants [

11,

12] (

Figure 1).

Maintaining safe and healthy indoor air quality (IAQ) in buildings presents a complex challenge, as it is influenced by a multitude of interacting factors [

13]. These include the intended use of the space, the architectural design and the specific characteristics of its ventilation system, the operating protocols employed within the building, and the prevailing climatic conditions. Consequently, effective mitigation strategies require the careful selection and appropriate integration of advanced air purification and disinfection technologies within heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems (HVAC) [

14].

The primary source of airborne pathogens within buildings is typically infected occupants, whose respiratory activities generate infectious aerosols [

15]. Pathogens may be introduced via outdoor air intakes, especially in regions with compromised air quality. HVAC systems, while often employing recirculation for energy efficiency, can inadvertently contribute to the redistribution of these pathogens [

16]. If recirculated air contains viable infectious agents, they can be drawn into the return air ductwork and subsequently disseminated throughout the building via the supply air stream. While filters are standard HVAC components, their efficacy against all pathogens, particularly smaller viral particles, is limited [

17]. Furthermore, the efficacy of various available air purification methods (

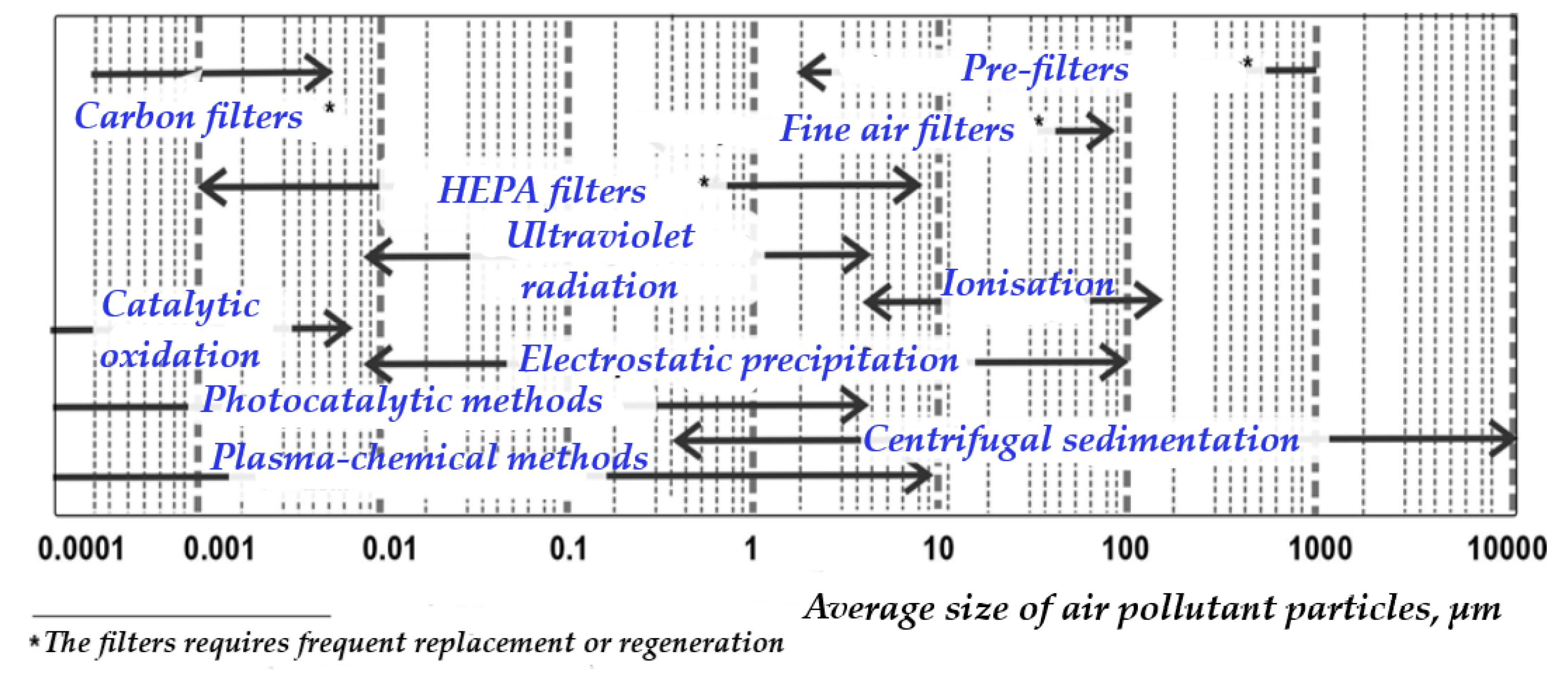

Figure 2) within HVAC systems can be substantially diminished by the limited residence time of aerosolised particles within the purifier's active zone under typical air exchange conditions.

A critical aspect of the performance of the HVAC system is filtration. Suboptimal filter selection, such as using filters with an inadequate Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) rating for the target pathogens, can significantly compromise the filtration barrier. Similarly, improper maintenance, including infrequent filter replacement or incorrect installation, can allow pathogens to penetrate the filter and enter the recirculated airstream. Furthermore, filters themselves can become reservoirs for microbial growth if not properly maintained, potentially exacerbating the problem. Beyond filtration, airflow dynamics and system hygiene play a crucial role in pathogen distribution. Poorly balanced airflow, often a consequence of suboptimal ductwork design or diffuser placement, can create stagnant zones that facilitate pathogen accumulation or, conversely, promote their widespread dissemination. Insufficient ventilation, characterised by an inadequate supply of fresh air, further compounds this risk by allowing pathogens at accumulate to higher concentrations. Inadequate system hygiene, including contaminated conduits and other components such as cooling coils and drain pans, promotes microbial proliferation and can contribute to the overall burden of airborne pathogens.

Photocatalytic and plasmochemical air disinfection methods, frequently coupled with filtration systems for the removal and ozone mitigation, have gained significant traction in contemporary applications due to their potential for the control of broad-spectrum pollutants [

18,

19]. However, translating these technologies, particularly photoplasma catalytic methods, to the dynamic aerodisperse flows characteristic of centralised ventilation systems presents substantial challenges [

27,

28]. Plasmochemical disinfection methods are inherently governed by the specific mechanisms and kinetics of the underlying plasmochemical reactions, which are further influenced by the unique chemical processes occurring within low-temperature plasmas and plasma jets as the aerodisperse flows pass through them [

21]. A more comprehensive understanding of these complex interactions is crucial for optimising the performance and reliability of these technologies in real-world HVAC applications.

Low-temperature plasma, generated via high-voltage discharge, interacts with these aerodisperse flows, and the discharge parameters directly influence the interaction time. Consequently, the design of the plasma-chemical treatment unit plays a critical role, directly affecting the intensity and duration of the plasma interaction with organic molecules present in the air stream. A common by-product of plasma-based air treatment is the generation of excess ozone, which requires its reduction to levels below established permissible limits (eg, 0.1 mg/m³ for occupational exposure [

29,

30]. The efficacy of ozone abatement depends on the specific destruction mechanism employed, whether photolytic, thermal or catalytic, each exhibiting distinct influencing factors [

31,

32]. For instance, the efficiency of catalytic ozone decomposition is modulated by the composition of the ozone-gas mixture, the design and contact surface area of the adsorber, the intensity of radiation (if applicable), temperature, humidity, airflow velocity, and the surface properties of the catalyst. Integrating photocatalytic filters within air purification systems offers several compelling advantages, including energy efficiency (low specific energy consumption), environmental benignity (decomposition into harmless by-products), and simplified maintenance requirements.

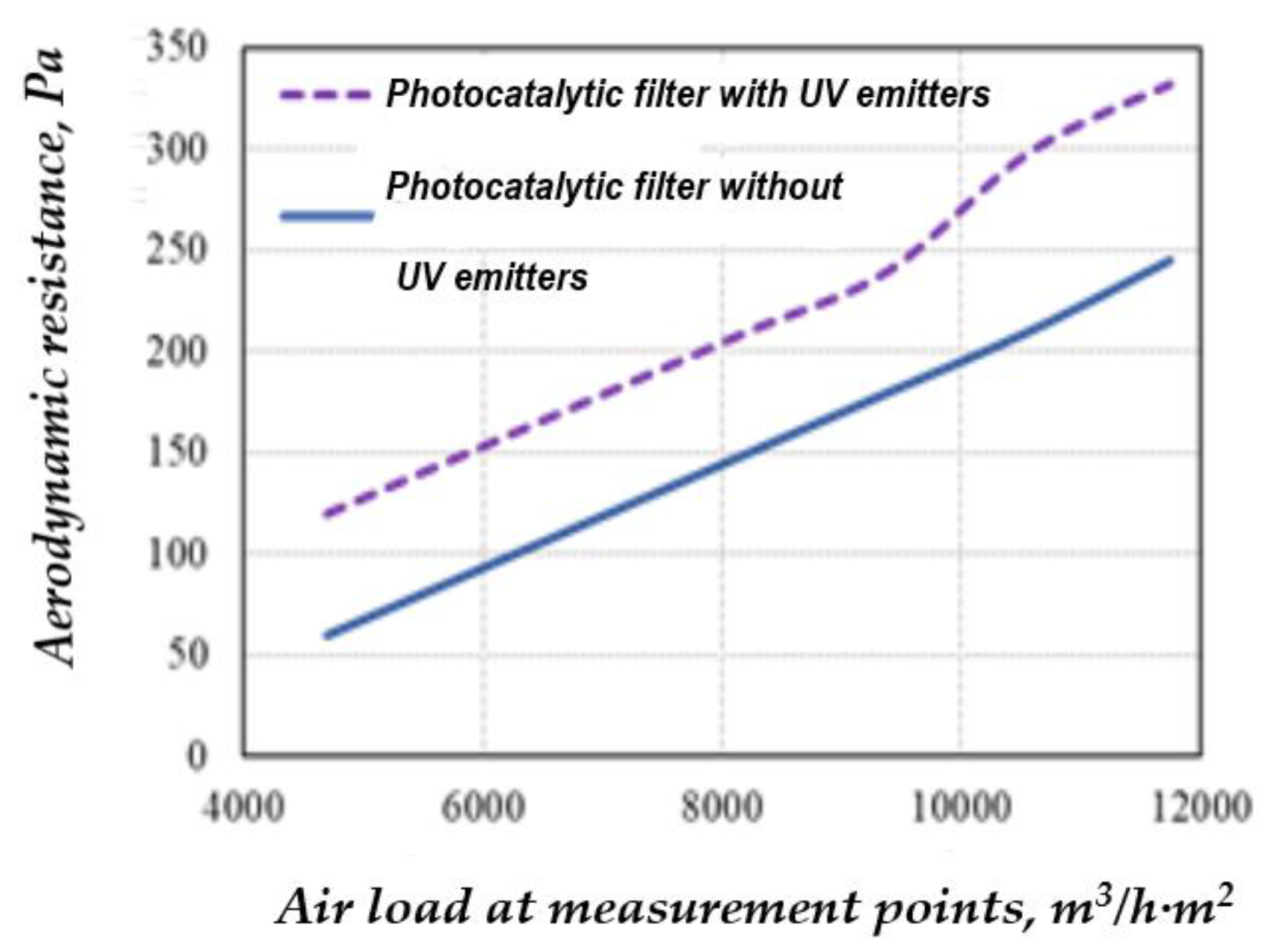

Finally, the efficacy of photocatalytic air purification is critically dependent on the confluence of factors related to the design and operation of the photocatalytic unit. The selection and strategic placement of the source of ultraviolet (UV) radiation is paramount, as the intensity and spectral characteristics of UV light directly influence the activation of the photocatalyst and the subsequent generation of reactive species responsible for pollutant degradation [

18,

29]. Furthermore, the aerodynamic resistance of the unit plays a significant role, impacting the airflow patterns and the residence time of pollutants within the reactor, thus affecting the overall purification efficiency. The material properties of the catalyst support matrix, including its composition and surface modification techniques used for photocatalyst immobilization, are also crucial considerations [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. These parameters influence the accessibility to pollutants, the rate of adsorption, and the efficiency of the photocatalytic reaction. A comprehensive understanding of the coupled heat and mass transfer phenomena within the porous catalyst structure is essential for optimising reactor performance [

38,

39]. Although energy conservation within HVAC systems has traditionally been approached through recirculating air exchange schemes incorporating rotary heat recoverers [

40,

41], recent public health crises have led to a reevaluation of these practices. Recommendations to limit the operation of the air conditioning system and minimize or eliminate indoor air recirculation have been implemented in some regions due to concerns about the transmission of airborne diseases. The absence of a harmonised international standard for HVAC systems that explicitly incorporates anti-pandemic measures underscores the need for further research and collaborative efforts to balance energy efficiency, indoor air quality, and public health considerations.

This article addresses the pressing need for effective air purification and disinfection strategies within building ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, particularly in light of increasing concerns about airborne transmission of infectious diseases. The prevalence of centralised ventilation systems in modern buildings, while offering advantages in terms of climate control and energy efficiency, can also inadvertently contribute to the rapid dissemination of airborne pathogens. Current approaches often do not provide adequate protection against these risks, highlighting a critical gap in existing HVAC technologies. Therefore, this work aims to develop and evaluate novel air purification and disinfection modules that integrate plasma chemistry and photocatalysis for seamless integration into centralised HVAC systems without requiring extensive system reconstruction. The overarching goal is to achieve a significant reduction in the pathogenic microflora, thereby minimising the risk of infection and contributing to a healthier indoor environment. This research is particularly relevant given the recent global health crises, which have underscored the vulnerability of indoor environments to airborne transmission and the urgent need for improved air disinfection strategies.

3. Discussion

To intensify the process of decomposition of excess ozone, the air is heated before being fed into the catalytic filter, which helps to increase the efficiency of the ozone destruction process on the catalyst surface at temperatures above 50 °C [

32]. Furthermore, maintaining an elevated air temperature within the device promotes the decomposition of organic impurities that accumulate on the surface of the catalytic filter [

43].

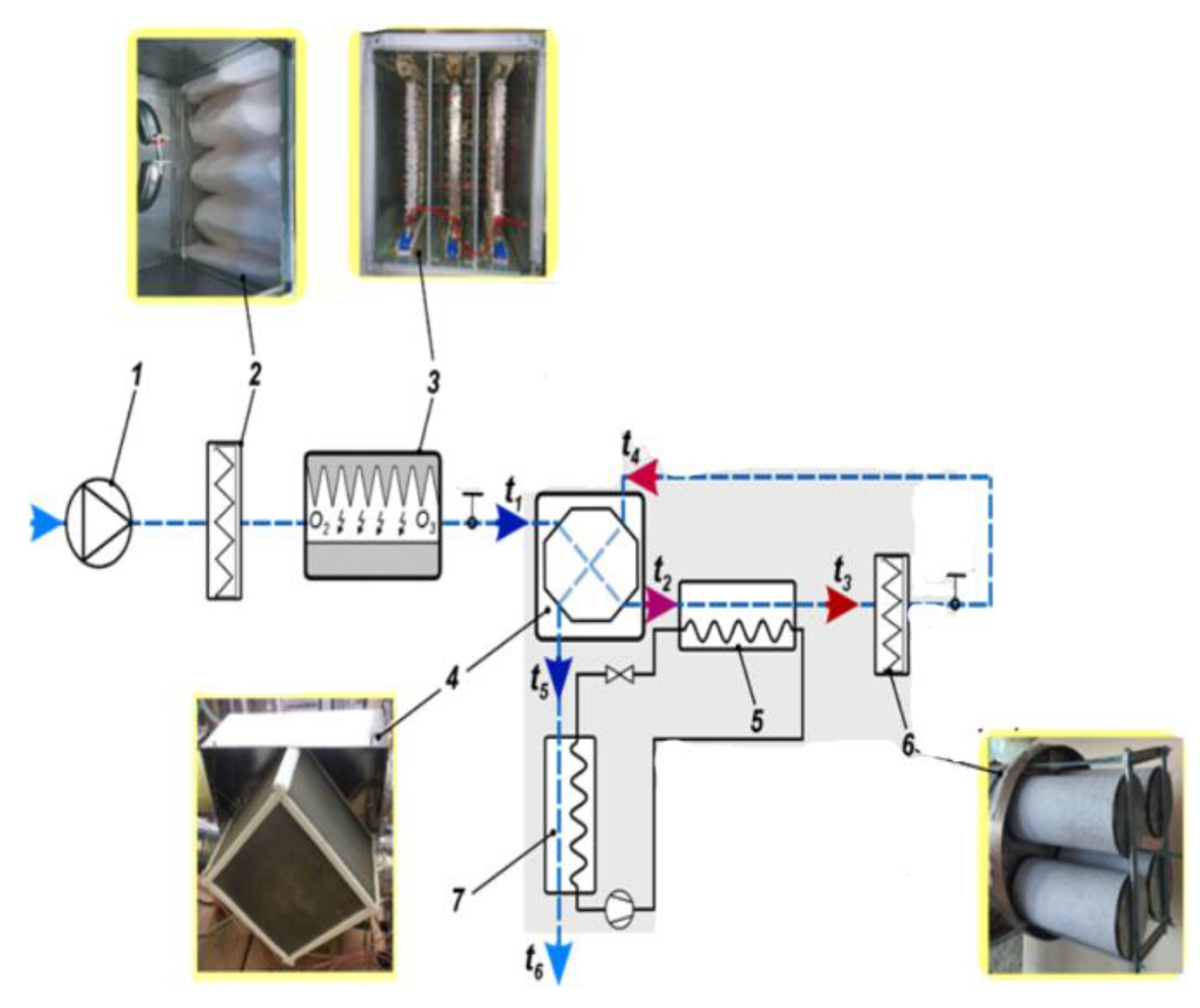

The technological scheme of the air purification and disinfection process with the combined catalytic-thermal decomposition system of excess ozone is shown in

Figure 11.

Reduction of energy consumption necessary for thermal treatment of air is achieved by heat recovery from the already heated purified air to the air, which is supplied for heating. The use of a heat pump in combination with a ‘air-to-air’ recuperative heat exchanger saves a significant part of energy spent on heating and allows to maintain within the required limits the temperature of heating and cooling of air. Realisation of the proposed air purification scheme allows reducing energy consumption for heating of aerodispersion by 7-8 times. The average efficiency of the recuperative heat exchanger is 0.65-0.70 and the heat pump conversion coefficient is 2.7-3.2.

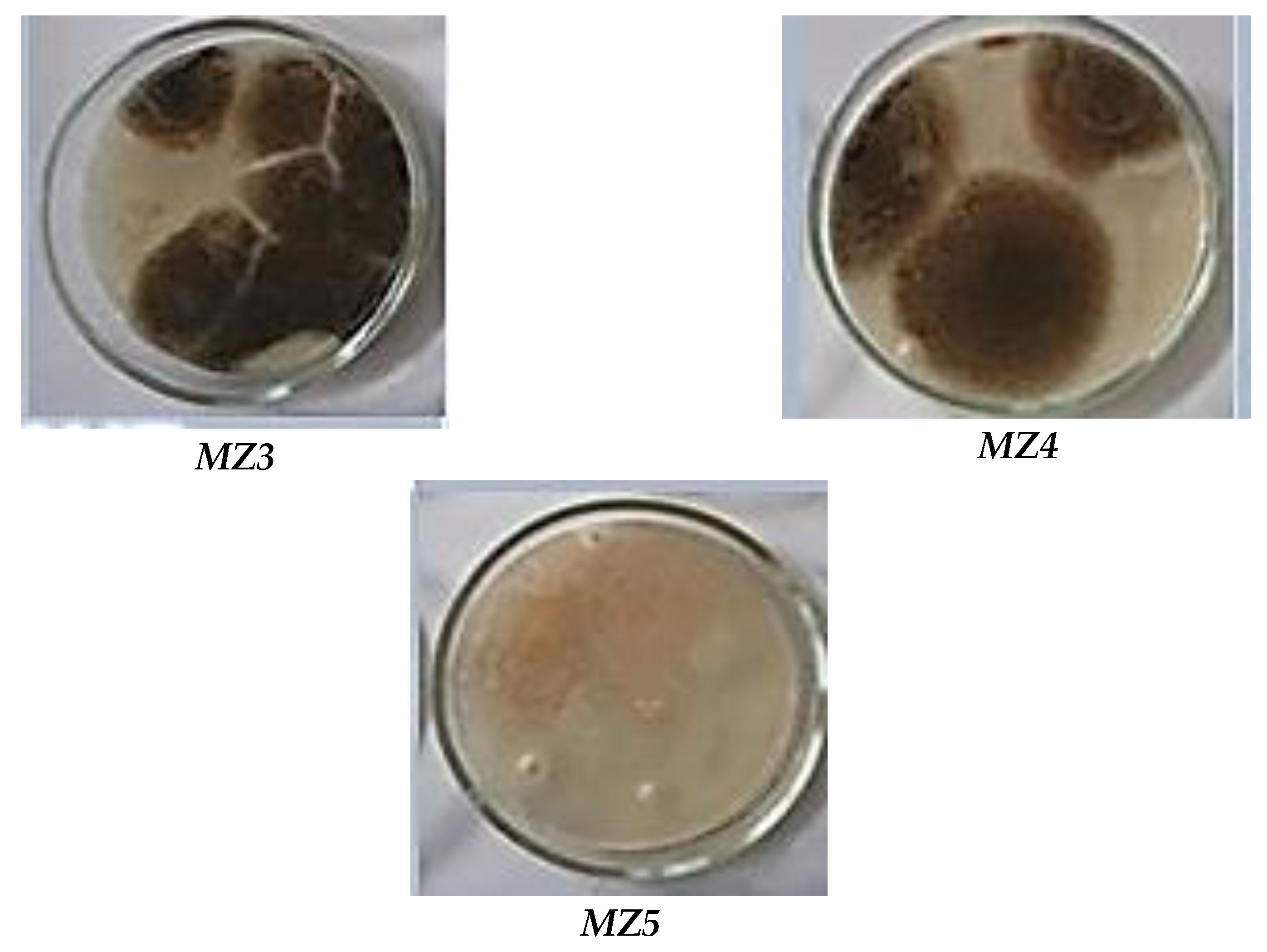

The results of microbiological studies of the air condition (

Figure 12) showed that a decrease in the number of microflora was observed already after the first day of equipment operation (

Figure 12c). After the third day of plant operation, no significant changes were detected in the samples taken.

During the microflora test period, the content in the room air environment after 3 days of the unit operation decreased by 60 %. In addition, the microflora content did not decrease, which may have been caused by the design flaws of the applied recuperator.

The results of laboratory studies and field tests showed that the depth and speed of aerodisperse microflora inactivation depend mainly on the volume concentration of atomic oxygen and ozone. The possibility of increasing the concentration of ozone in the plasma-chemical air treatment module is limited by the ability of the adsorption-catalytic unit to convert excess ozone into molecular oxygen before air supply to the room.

4. Materials and Methods

This section provides a detailed account of the experimental setup, materials, and procedures used to evaluate the performance of a pilot-experimental air purification system. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of an integrated system, which combines plasma chemistry and filtration, in mitigating airborne particulate matter and organic compound concentrations under controlled conditions, simulating real-world HVAC applications.

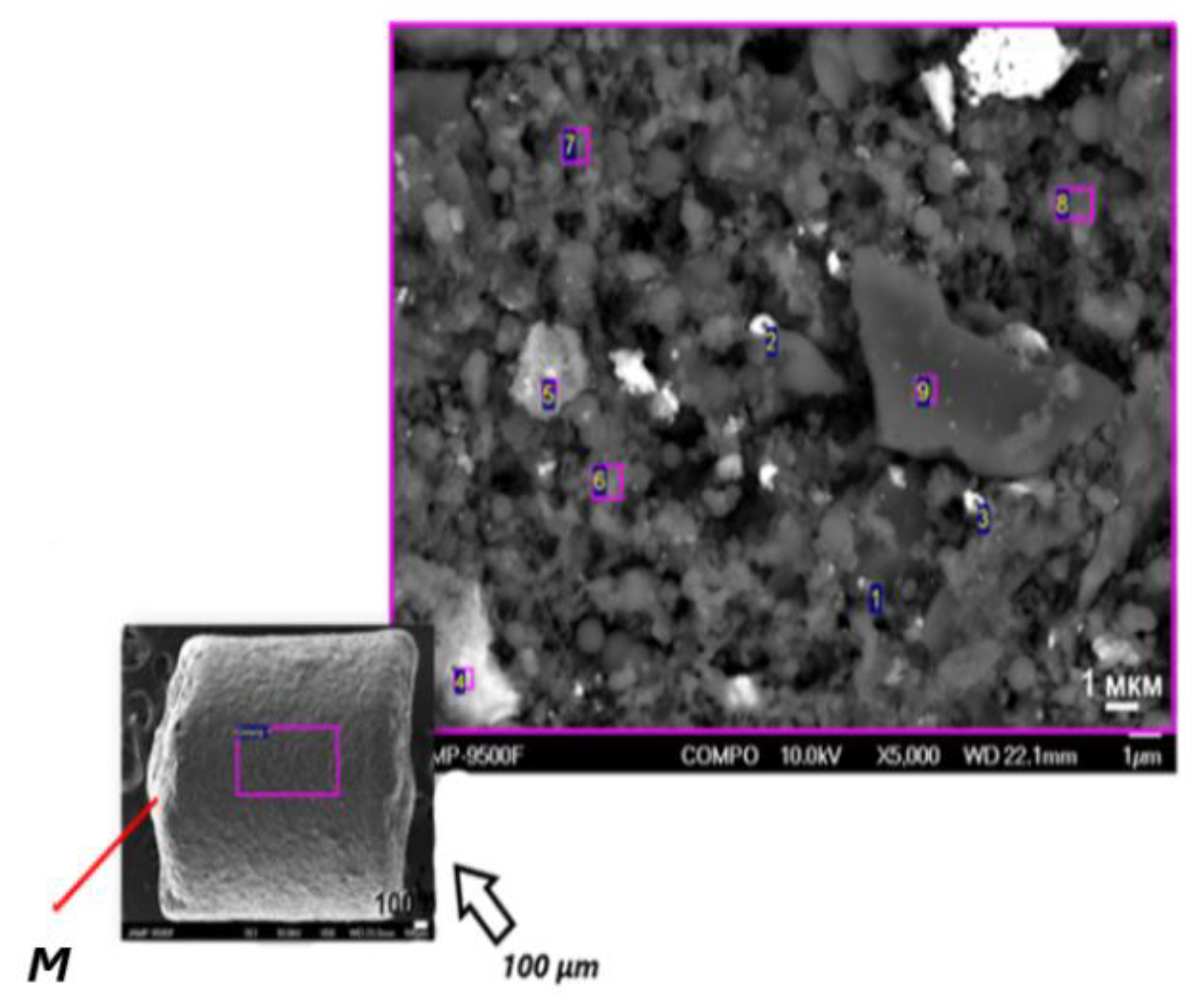

4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis of Adsorbent Granules

To comprehensively characterise the adsorbent granules, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed. This technique was used to assess several key morphological and compositional attributes, including: granule surface morphology; uniformity of component distribution; dispersity of the mixture. These analyses were performed using a JEOL Auger Micro Probe JAMP 9500F (JEOL, Japan). This instrument provides high-resolution imaging and elemental analysis, enabling a detailed characterisation of the adsorbent granules. The resulting SEM micrographs were analysed to determine the average particle size, the pore size distribution, and the surface area of the adsorbent granules. Elemental analysis was performed using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to confirm the composition and distribution of the components.

4.2. Surface Area Analysis

The specific surface areas (SBET) of the samples were evaluated using the standard Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method for nitrogen adsorption data. The synthesised zeolites were degassed overnight at 250 ° C under vacuum prior to measurement. N2 adsorption-desorption measurements were carried out at 77 K in the range of relative pressure p/p0 from 0.01 to 0.99, using the ASAP 2020 volumetric adsorption analyzer (Micromeritics).

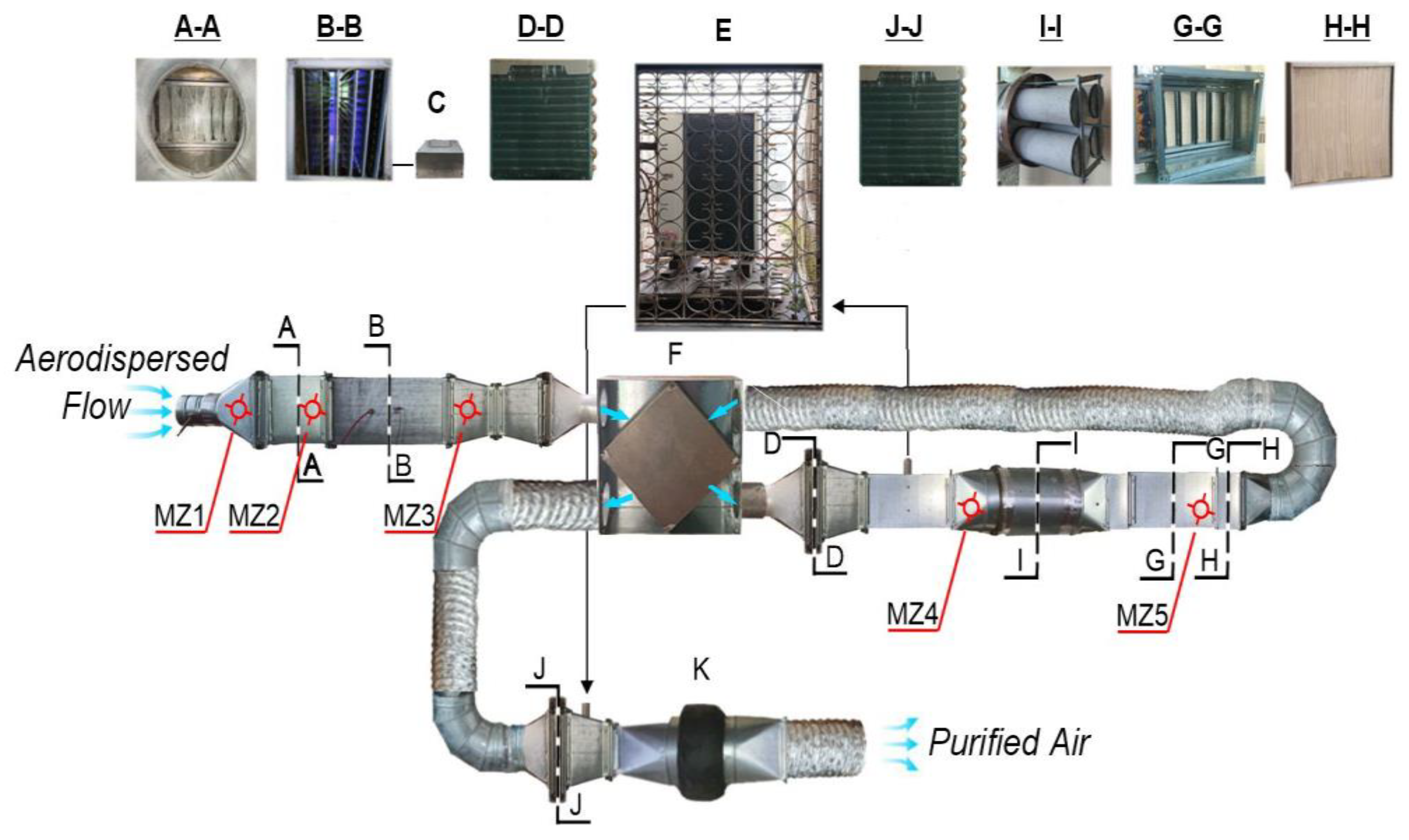

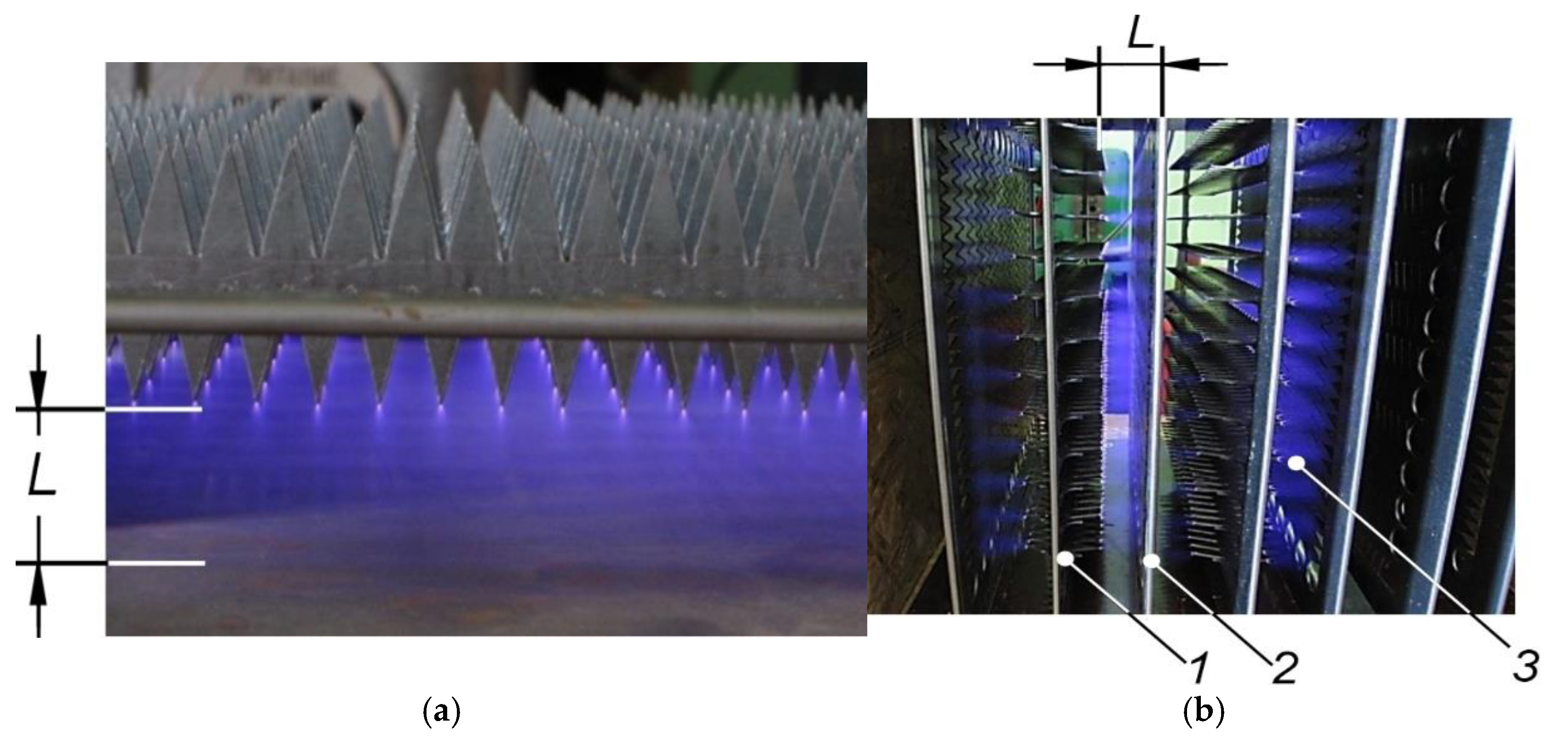

4.3. Construction of the Plasma-Chemical Air Treatment Module

The development of the plasma-chemical air purification module focused on the design and optimisation of a low-temperature plasma generator for efficient aerodisperse treatment. The core component of the module was a low temperature plasma generator (

Figure 13), connected to a high voltage power supply with an adjustable output voltage.

The structural elements of the corona discharge generation section (

Figure 4a) within the plasma-chemical module were mounted in a housing, forming a cassette assembly (

Figure 13b). A plasma-chemical module was developed with the following technical parameters and operating conditions: overall dimensions 320x260x260 mm; interelectrode distance: 20–25 mm; voltage applied to the low-temperature plasma unit up to 20 kV; electric field intensity between electrodes: up to 8×10³ V/cm; air exchange rate up to 700 m³/h; operating temperature range 17–30°C; relative air humidity 45–70% at 25 ° C.

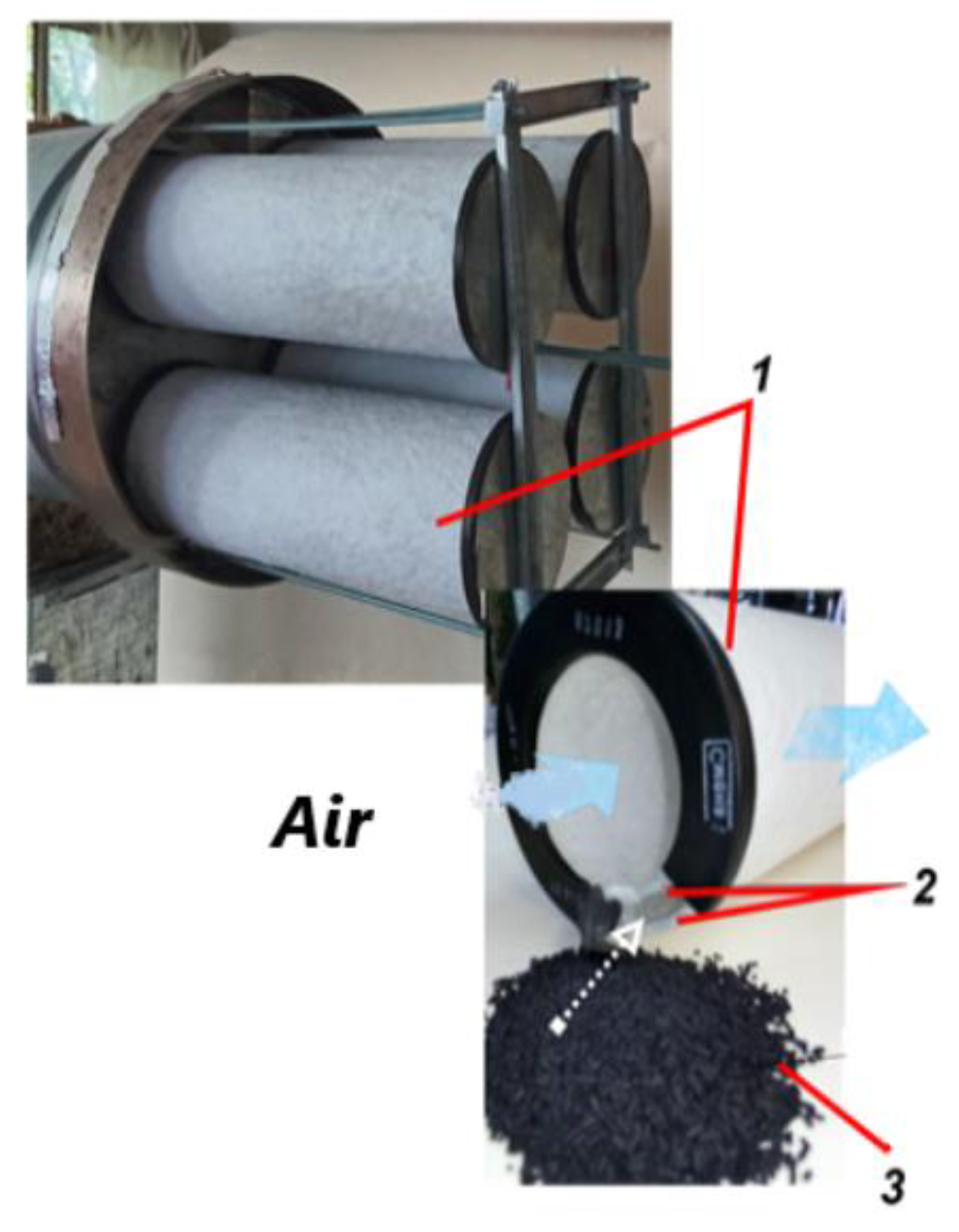

Following plasmachemical purification, the air stream enters an adsorption-catalytic module (

Figure 14), which consists of a set of cartridges housed within a box. Each cartridge is composed of two layers of G-class filter material, and the space between them filled with adsorbent granules.

The granules are formed from a mixture of carbon particles and calcium aluminate. Aerodisperse particles become electrically charged within the corona discharge zone and subsequently deposit and are electrostatically retained on the surface of the filter layer

2 (

Figure 14). Thus, the filter surface acts as a barrier, preventing solid particles from reaching the surface of adsorbent-catalyst

3. The porous surface of the adsorbent adsorbs molecular compounds and excess ozone molecules, followed by degradation via heterogeneous catalysis.

4.4. Construction of Tablet-Type Photocatalytic (PC) Air Purification Modules

Tablet-type PC air purification modules were constructed (

Figure 15) to facilitate photocatalytic air treatment within ventilation systems.

Each module consisted of a PC filter and UV emitters, assembled within a Z-line frame. To allow easy maintenance and replacement, the modules were designed for installation within standard filter boxes in the ventilation system.

The UV-radiation generators 3 were strategically positioned to ensure maximum direct illumination of the photocatalytic surface, maintaining an optimal radiation intensity of 1.2-2.0 mW/cm².

Furthermore, a polished aluminium screen 4 was incorporated into the module design to enhance illumination. This screen, reflecting up to 80% of light within the 300-400 nm wavelength range, provided additional illumination through reflected light, thus maximizing the efficiency of the photocatalytic process.

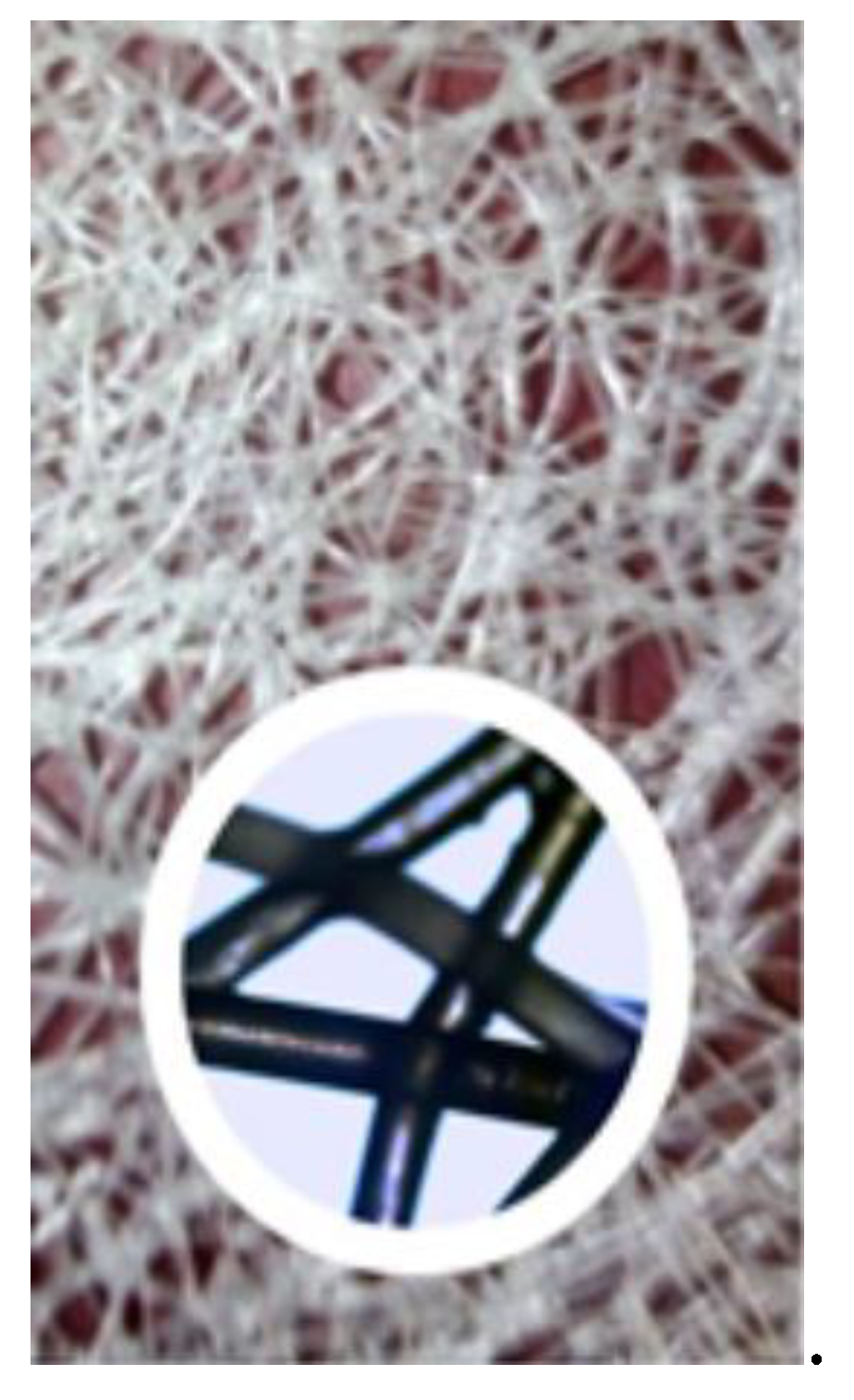

4.5. Characterisation and Fabrication of Photocatalytic (PC) Modules

4.5.1. Material Selection and Characterisation

For the photocatalytic material, highly dispersed crystalline titanium dioxide (TiO₂) AEROXIDE® TiO₂ P25 (EVONIK Co.) was chosen. This material, characterised by nanoparticles ranging from 10 to 45 nm, exhibited a specific surface area of 50 ± 15 m²/g. TiO2 powder consisted of a mixed-phase composition, with 80-90% anatase and 10-20% rutile phases, as previously documented [

36].

A nonwoven fabric composed of polypropylene (PP) fibres served as the support matrix for the photocatalyst. This fabric was selected due to its inherent macroporous structure, which provided an initial aerodynamic resistance of 10-30 Pa. This selection strategy was designed to minimise the increase in aerodynamic resistance that would occur during surface modification, as micropores and partially mesopores were expected to be occluded by the deposited catalyst layer [

44,

45].

4.5.2. PC Module Fabrication Process

A multistage fabrication process was used to create PC modules on polypropylene membranes. This process was designed to optimise the performance characteristics of PC filters by precisely controlling the surface modification of the carrier matrix. The fabrication process included the following steps: formation of the matrix geometry and composition, modification of the carrier matrix surface by associated processes, equipping with UV generators, and framing of the photocatalytic module. The carrier matrix consisted of 2 layers of fibrous PP membrane with a metal frame between them for structural rigidity. Due to corrugation with corrugation opening angle of 90o, surface development was achieved 1.4 times. After matrix formation, the photocatalyst was applied on the surface. In the work a modification method was applied that combined methods of immersion in 3% dispersive hydrogen medium with catalyst at a fixed temperature and further filtration through the porous space of the matrix was applied in the work. The modification was carried out in an innovative unit of type PF-200, its operation of which is based on the principles of discrete pulse energy injection into heterogeneous systems [

45,

46,

47].

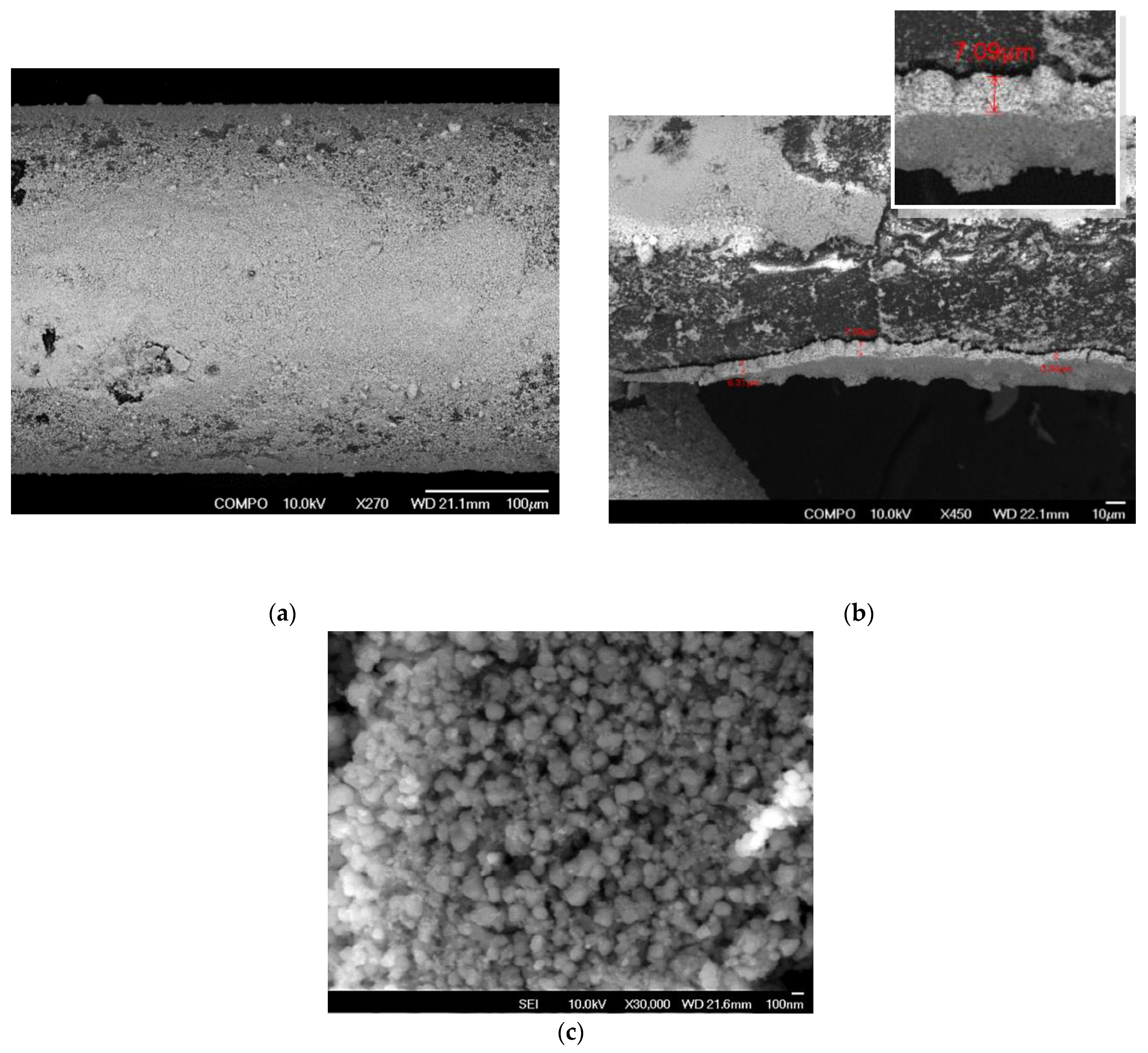

4.5.3. Structural and Topological Characterisation of the AEROXIDE® TiO2 P25 Catalyst Layer

The structural and topological characteristics of the AEROXIDE® TiO2 P25 catalyst layer deposited on the carrier fibres of the polymer matrix were evaluated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM analysis was conducted at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV to visualize and assess the morphology and distribution of the catalyst on the individual fibers of the support matrix.

4.6. Polymer Cross-Flow Plate Recuperator for Air Purification System

In centralised ventilation systems utilizing rotary heat recovery units, there is a potential for partial air transfer from the exhaust pipe to the supply duct. This phenomenon can facilitate the dissemination of pathogenic microflora throughout the building. Plate-type recuperators, which achieve heat transfer through a solid heat exchange surface, eliminating airflow mixing, address these limitations. For the air purification system developed in this study, a polymer cross-flow plate recuperator was designed and subsequently tested (

Figure 16).

The heat exchange surface of the recuperator was constructed from finned plates with a wall thickness of 0.15 mm and a fin height of 2 mm. These plates were assembled into a heat exchange package, forming cross-channels with dimensions of 6×2 mm. The performance of the recuperative heat exchanger was evaluated through a series of controlled laboratory tests. The results demonstrated that at an air velocity of 0.75 m/s within the channels, the recuperator achieved a thermal efficiency of 0.9. However, as the air velocity increased to 3 m/s, the thermal efficiency decreased to 0.6. These tests were conducted under controlled conditions, simulating typical operating parameters of ventilation systems.

4.7. Methodology for Assessing Microbiological Air Pollution

Assessment of microbiological air pollution was carried out using both impaction and sedimentation methods to collect airborne microorganisms in culture media [

48,

49]. Meat peptone agar (MPA), a standard medium suitable for the cultivation of a wide range of microorganisms, was selected as the culture medium. During the experimental studies, air was drawn through the pilot plant at a controlled flow rate. Sterile Petri dishes containing MPA were placed at designated monitoring points (

Figure 4).

A qualitative assessment of the inhibition of fungal growth of eukaryotic organisms (mould fungi) was performed at each stage of the aerodisperse medium disinfection process. Selected air microflora samples collected from the monitoring points were incubated in a thermostat at 37 °C for 142 hours.

5. Conclusions

The implementation of UV light for polluted air purification was recognised as a technique mimicking natural processes, demonstrating substantial potential for development as a key air treatment technology. However, significant breakthroughs were still required in several areas. While contemporary academic investigations primarily focused on material development, the engineering aspects for commercialisation necessitated a deeper examination of practical issues. These included the prevention of photocatalyst fouling/deactivation, facilitation of facile and low-temperature photocatalyst immobilisation on supports, and the design of efficient and cost-effective reactors. Future research on photocatalytic air purification was deemed essential to address these practical concerns, bridging the gap between laboratory results and real-world applications.

On the basis of the comprehensive research conducted, it was concluded that the disinfection of air through a combined plasmochemical and photocatalytic approach, supplemented by a catalytic-thermal decomposition system for excess ozone, effectively removed molecular pollutants and reduced airborne microbial contamination to safe levels. This methodology was demonstrated to contribute to the mitigation of risks associated with infectious diseases. The efficacy of the developed equipment was further substantiated by field tests, which confirmed the stability of the operational characteristics of the proposed plasmochemical and photocatalytic disinfection modules.

Implementing the results from this study facilitates retrofitting of existing building ventilation and air conditioning systems with additional modules for the inactivation and removal of molecular pollutants. A pressing need for this type of equipment was identified in both temporary occupancy locations (e.g. administrative buildings, retail stores, clinics) and permanent occupancy settings (e.g., business centres, educational institutions, hospitals), thereby presenting opportunities for the application of the proposed equipment in centralised ventilation and air conditioning systems.

Figure 1.

Pathways to the spread of pathogens in areas with centralized (HVAC) systems.

Figure 1.

Pathways to the spread of pathogens in areas with centralized (HVAC) systems.

Figure 2.

Operating ranges of current air cleaning and disinfection techniques [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Figure 2.

Operating ranges of current air cleaning and disinfection techniques [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

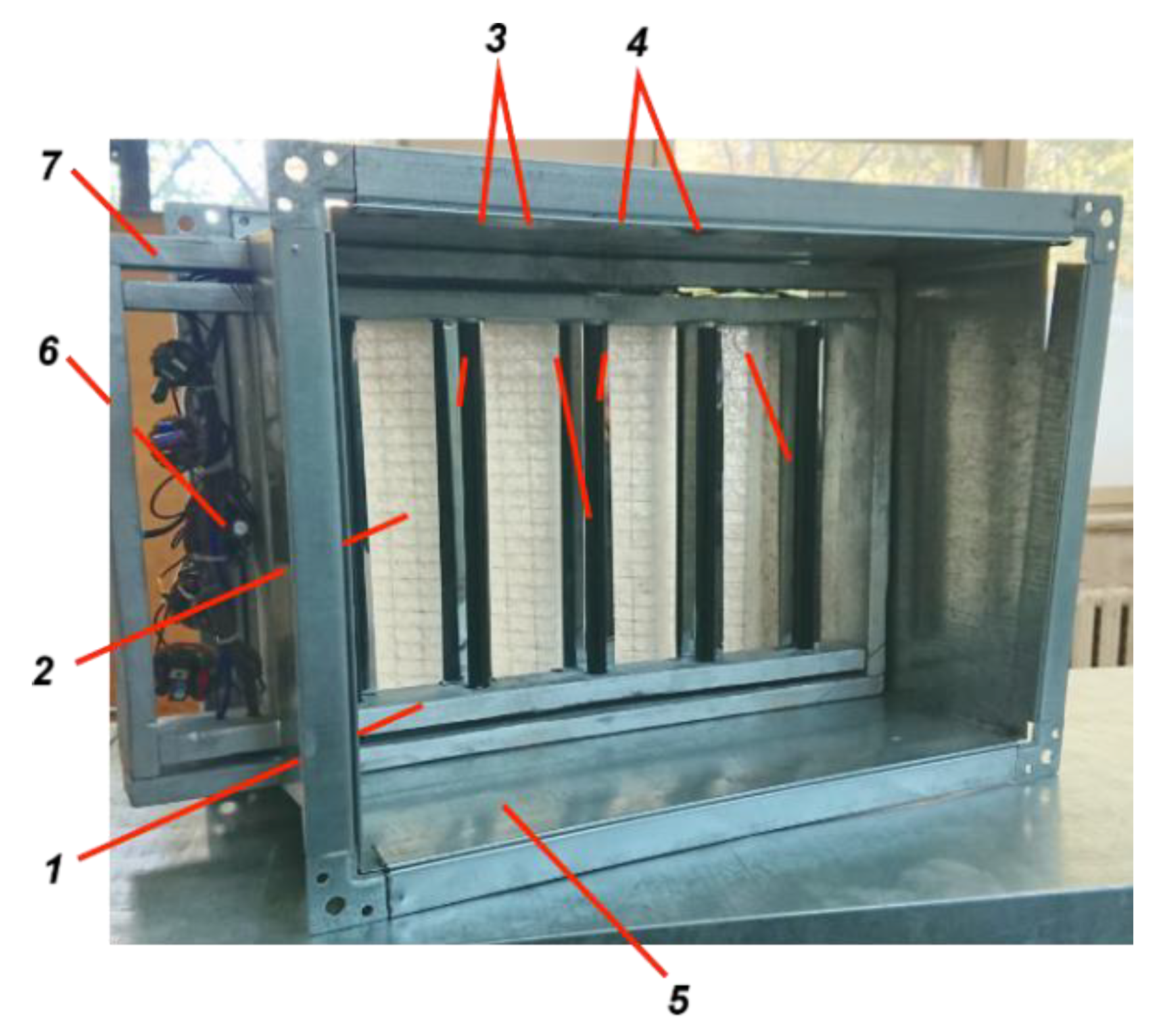

Figure 3.

Key components of the pilot-experimental installation.

Figure 3.

Key components of the pilot-experimental installation.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram and modular components of the experimental installation to investigate complex air purification and disinfection processes in ventilation systems: A – coarse filter; B – plasma ioniser; C – high-voltage power supply; D – heat pump condenser; E – heat pump; F – recuperative heat exchanger; G – photocatalytic module; H – output filter; I - adsorption catalytic module; J – heat pump evaporator; K – exhaust fan with performance control; MZ1... MZ5 - air microflora monitoring zones.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram and modular components of the experimental installation to investigate complex air purification and disinfection processes in ventilation systems: A – coarse filter; B – plasma ioniser; C – high-voltage power supply; D – heat pump condenser; E – heat pump; F – recuperative heat exchanger; G – photocatalytic module; H – output filter; I - adsorption catalytic module; J – heat pump evaporator; K – exhaust fan with performance control; MZ1... MZ5 - air microflora monitoring zones.

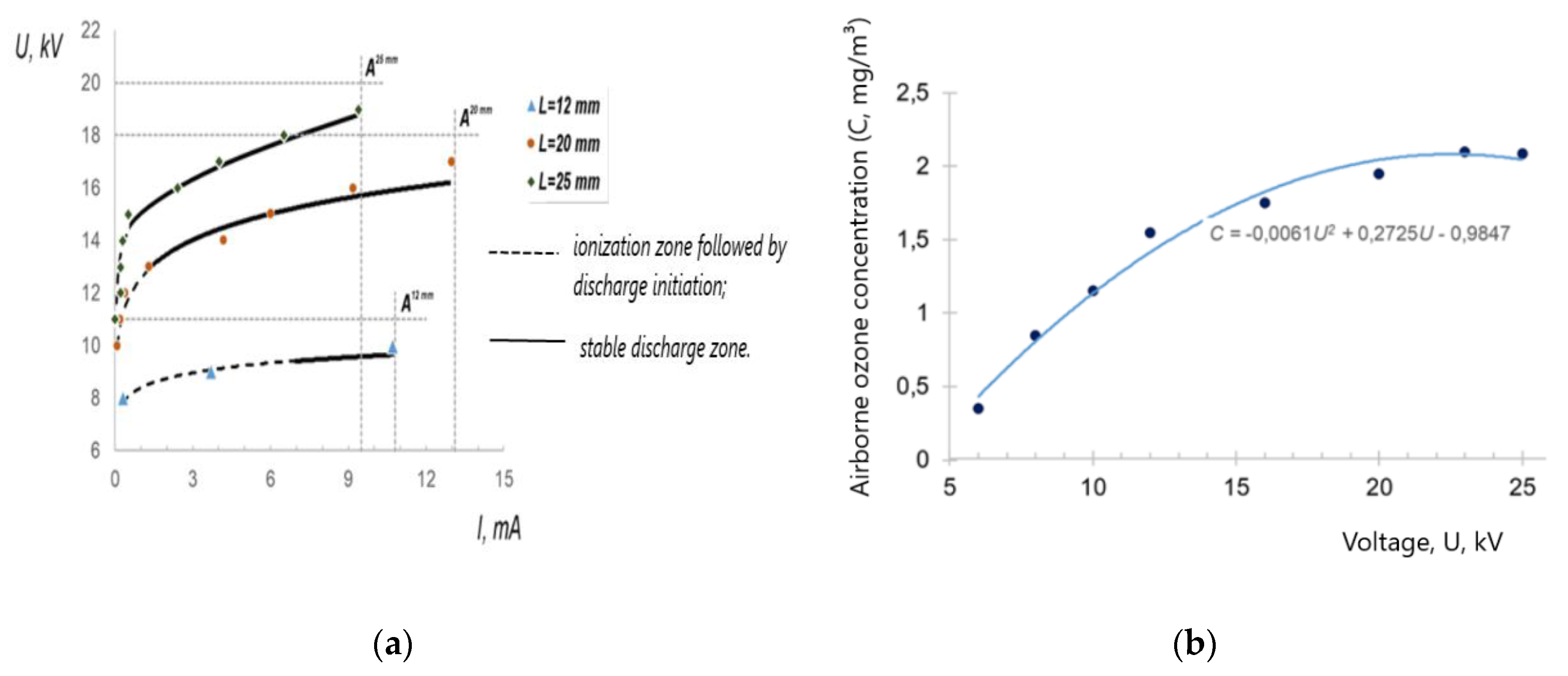

Figure 5.

Experimental determination of stable operating parameters for low temperature plasma generation: (a) Generator voltage-current characteristics (VAC) at variable L; (b) Ozone synthesis (post-generator at MZ3) as a function of applied voltage at an air velocity of 1.2 m/s and a temperature of 18–20 °C; A – air gap breakdown points; L – interelectrode distance (arc gap width).

Figure 5.

Experimental determination of stable operating parameters for low temperature plasma generation: (a) Generator voltage-current characteristics (VAC) at variable L; (b) Ozone synthesis (post-generator at MZ3) as a function of applied voltage at an air velocity of 1.2 m/s and a temperature of 18–20 °C; A – air gap breakdown points; L – interelectrode distance (arc gap width).

Figure 6.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the adsorbent-catalytic granule: overview at 50x magnification (left) and detailed surface morphology at 5000x magnification (right), M, magnified structure.

Figure 6.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the adsorbent-catalytic granule: overview at 50x magnification (left) and detailed surface morphology at 5000x magnification (right), M, magnified structure.

Figure 7.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the unmodified polymer matrix carrier fibres.

Figure 7.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the unmodified polymer matrix carrier fibres.

Figure 8.

Cross-sectional SEM topography of the TiO2 matrix coating, illustrating surface features at (a) 270x, (b) 450x and (c) 30000x magnifications.

Figure 8.

Cross-sectional SEM topography of the TiO2 matrix coating, illustrating surface features at (a) 270x, (b) 450x and (c) 30000x magnifications.

Figure 9.

Aerodynamic characteristics of the photocatalytic air disinfection module.

Figure 9.

Aerodynamic characteristics of the photocatalytic air disinfection module.

Figure 10.

Viable mould fungus colonies observed in culture medium after sampling at locations detailed in

Figure 4.

Figure 10.

Viable mould fungus colonies observed in culture medium after sampling at locations detailed in

Figure 4.

Figure 11.

Block diagram of energy-efficient air purification and disinfection: 1 - blower fan; 2 - coarse filter; 3 - bipolar plasma ioniser; 4 - heat exchanger (recuperator); 5 - heat pump evaporator ; 6 - adsorption-catalytic module, 7 - heat pump condenser.

Figure 11.

Block diagram of energy-efficient air purification and disinfection: 1 - blower fan; 2 - coarse filter; 3 - bipolar plasma ioniser; 4 - heat exchanger (recuperator); 5 - heat pump evaporator ; 6 - adsorption-catalytic module, 7 - heat pump condenser.

Figure 12.

Samples of indoor air microflora: (a) initial (before starting the plant); (b) after 6 hours of plant operation; (c) after 9 hours; (d) after 10 hours; (e) after 18 hours; (f) after 28 hours of module operation of the plant.

Figure 12.

Samples of indoor air microflora: (a) initial (before starting the plant); (b) after 6 hours of plant operation; (c) after 9 hours; (d) after 10 hours; (e) after 18 hours; (f) after 28 hours of module operation of the plant.

Figure 13.

Design of the low-temperature plasma generation module: (a) Stable low-temperature plasma discharge in a single section; (b) Sectional arrangement of corona electrodes and counterpolarity plates within the low-temperature plasma generation unit; 1 – saw-toothed corona electrodes; 2 – plate electrodes; 3 – corona discharge glow; L - interelectrode distance (arc gap width.

Figure 13.

Design of the low-temperature plasma generation module: (a) Stable low-temperature plasma discharge in a single section; (b) Sectional arrangement of corona electrodes and counterpolarity plates within the low-temperature plasma generation unit; 1 – saw-toothed corona electrodes; 2 – plate electrodes; 3 – corona discharge glow; L - interelectrode distance (arc gap width.

Figure 14.

Adsorption-catalytic module: 1 – cartridge, 2 – filter layers, 3 – adsorption-catalytic granular layer.

Figure 14.

Adsorption-catalytic module: 1 – cartridge, 2 – filter layers, 3 – adsorption-catalytic granular layer.

Figure 15.

Photocatalytic air disinfection module: 1 - PV cassette; 2 - PV filter; 3 - UV generator; 4 - reflective screen; 5 - filter box; 6 - UV lamp control unit; 7 - mounting frame.

Figure 15.

Photocatalytic air disinfection module: 1 - PV cassette; 2 - PV filter; 3 - UV generator; 4 - reflective screen; 5 - filter box; 6 - UV lamp control unit; 7 - mounting frame.

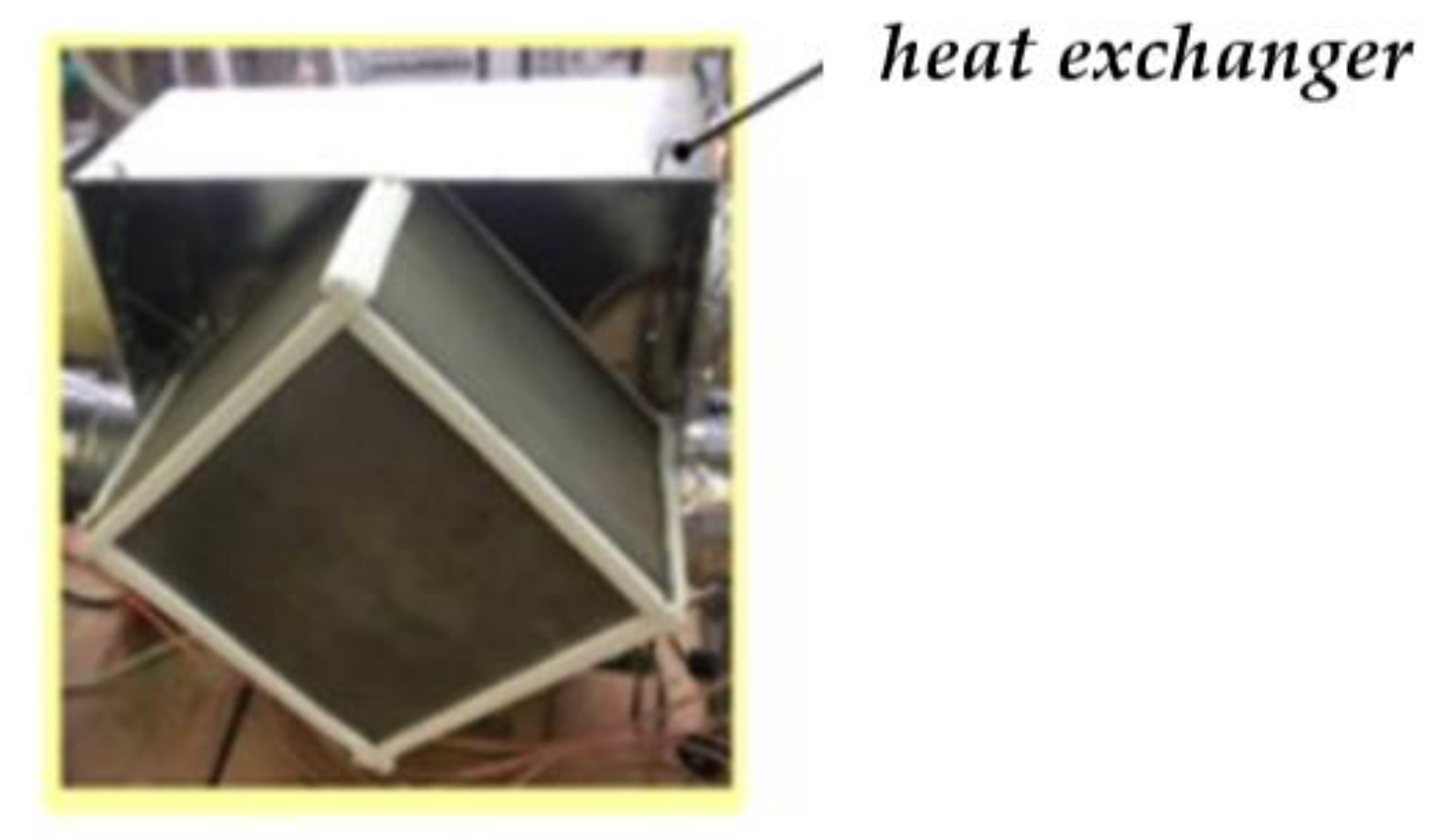

Figure 16.

Polymer cross-fin plate recuperative heat exchanger for air purification system.

Figure 16.

Polymer cross-fin plate recuperative heat exchanger for air purification system.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of the adsorption-catalytic granule (weight %).

Table 1.

Elemental composition of the adsorption-catalytic granule (weight %).

| Point |

C |

O |

Na |

Mg |

Al |

Si |

S |

K |

Ca |

Fe |

| 1 |

74.60 |

17.21 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

2.49 |

3.16 |

0.23 |

0.00 |

2.29 |

0.00 |

| 2 |

55.12 |

13.67 |

0.06 |

1.82 |

2.27 |

10.20 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

09.02 |

7.82 |

| 3 |

66.38 |

21.32 |

0.09 |

0.22 |

3.54 |

3.93 |

0.20 |

0.14 |

02.03 |

2.14 |

| 4 |

39.80 |

33.75 |

0.99 |

0.43 |

11.01 |

10.74 |

0.06 |

0.50 |

1.16 |

1.56 |

| 5 |

78.80 |

12.59 |

0.00 |

0.95 |

0.54 |

1.10 |

2.63 |

0.00 |

0.71 |

2.68 |

| 6 |

94.63 |

3.78 |

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.39 |

0.47 |

0.38 |

0.02 |

0.24 |

0.07 |

| 7 |

97.29 |

1.99 |

0.08 |

0.00 |

0.14 |

0.08 |

0.27 |

0.00 |

0.16 |

0.00 |

| 8 |

95.53 |

2.86 |

0.03 |

0.08 |

0.39 |

0.56 |

0.45 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.00 |

| 9 |

96.58 |

2.84 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.00 |

0.07 |

0.42 |

0.07 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the MZ aerodisperse system at the monitoring point.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the MZ aerodisperse system at the monitoring point.

| Parameters |

Monitoring Points |

| duration of operation of the purification: 30 min. |

MZ1 |

MZ2 |

MZ3 |

MZ4 |

MZ3 |

| content of dispersed particles smaller than 2.5 µm, µg/m3

|

30.0 |

15.0 |

13.0 |

9.0 |

8.0 |

| ozone concentration, mg/m3

|

0.000 |

0.153 |

4.6 |

0.342 |

0.095 |

| relative humidity, % |

58.0 |

58.0 |

58.0 |

57.0 |

56.0 |