Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights

- Data driven discovery and symbolic regression research, hermeneutic review, and theories analysis about the origin of the universe.

- Inflationary universe, Big Bang and quantum foam assumed, led to an entropic, standard-model comprehensive, universe, adding an approach to the main current problems between observations, cosmology and theories.

- Dimensional analysis to tackle on the CCP. It seems to show and point towards a quintessence-flat mass interactions universe. Three theories are highlighted, and it includes the possibility for co-varying universal constants, and either a constant Λ after an exponential Λ-space coupled Λ decrease, or a constantly flickering (wavy / steady-state related) Λ after that exponential Λ-space coupled Λ decrease.

Introduction

Theory and Calculation

Dark Energy or Not? The CCP

Theory and Calculation

“... the unit of mass is deduced from the units of time and length, combined with the fact of universal gravitation. The astronomical unit of mass is that mass which attracts another body placed at the unit of distance so as to produce in that body the unit of acceleration... If, as in the astronomical system the unit of mass is defined with respect to its attractive power, the dimensions of M are L3T−2.” Maxwell [179]. [178], p. 6

Conclusion

- After the review of topical, broad physics and philosophical bibliography, three main theories were proposed due to their completeness, matching some other theories that were tackling more specific particular problems between theories and observations, converging in mirror-like universe, conformal and/or cyclic, cosmology (CCC), and either steady-state and/or flickering Λ, matching other proposals such as freeze-out, and whether multiple Big Bangs [43,47,50,68] or microcyclic “universes” [50,166,196], they would fit well with the observations, and tackle properly the CCP. One might highlight some interesting words by Wang & Unruh [196]: “The spacetime dynamics sourced by this large negative λeff would be similar to the cyclic model of the universe in the sense that at small scales every point in space is a “micro-cyclic universe” which is following an eternal series of oscillations between expansions and contractions” [196], p. 1; “Moreover, if the bare cosmological constant λB is dominant, the size of each “micro-universe” would increase a tiny bit at a slowly accelerating rate during each micro-cycle of the oscillation due to the weak parametric resonance effect produced by the fluctuations of the quantum vacuum stress energy tensor.” [196], p. 1. It can be inferred substantiated by other proposals, that not a driving-force, but a “driving-force” or some kind of quintessence spacetime energy is either driving the expansion, being driven with the expansion of spacetime, or both, as hereby proposed (it was set as m4 in GR framework, or m2 · s2 where mass M0 is set as a kinetic mass M—μ ratio integrating that dimension in the driving energy, for a QM-GR unified framework). However, it was noticed that, if the previous can be matched with dark energy, gravitational constant G can also be related or equated with that particular energy in the beginning (GG), and with mass locally (G), pertaining, perhaps, to different minute-layouts or stages for entropy-spacetime relationship.

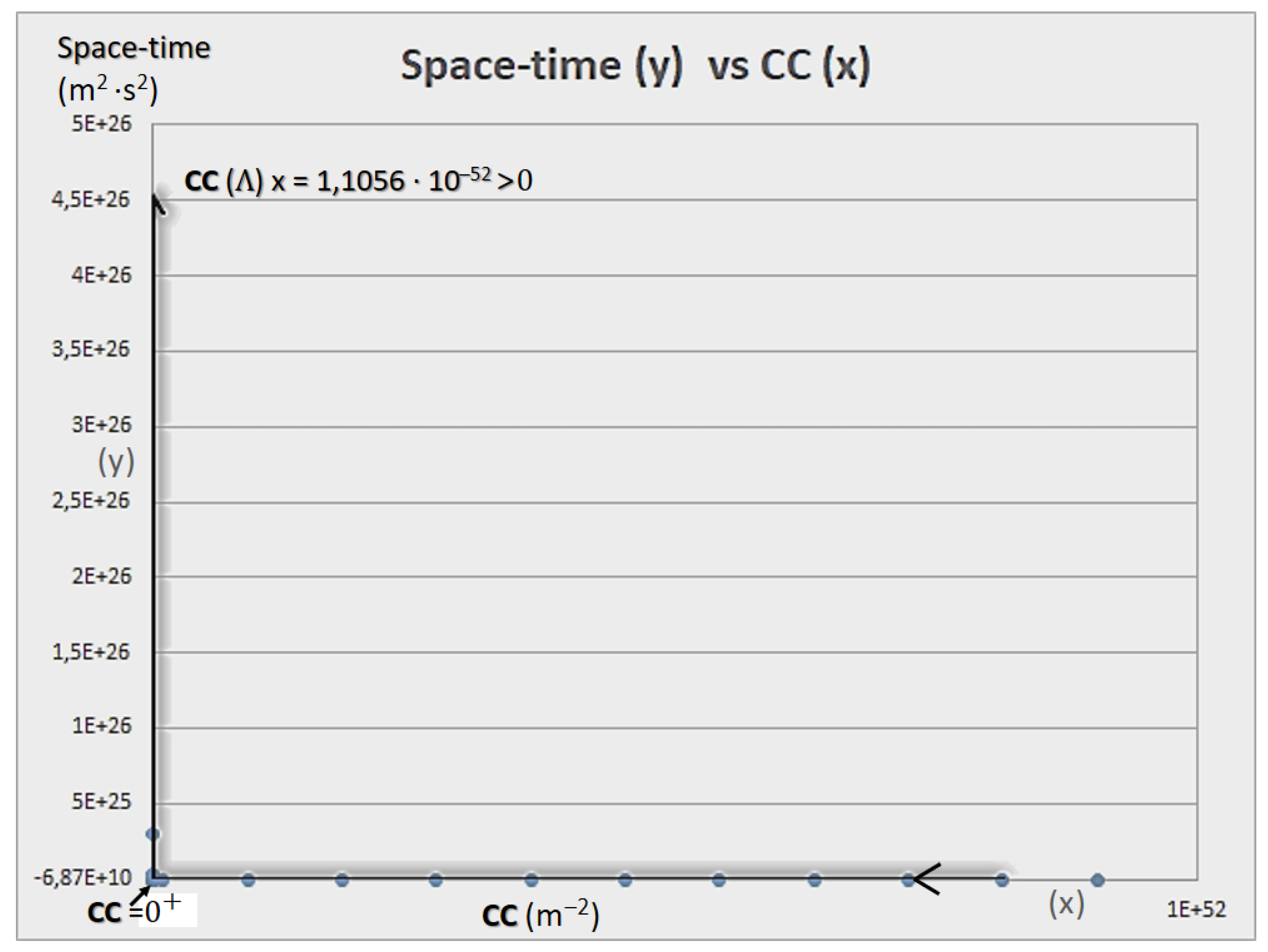

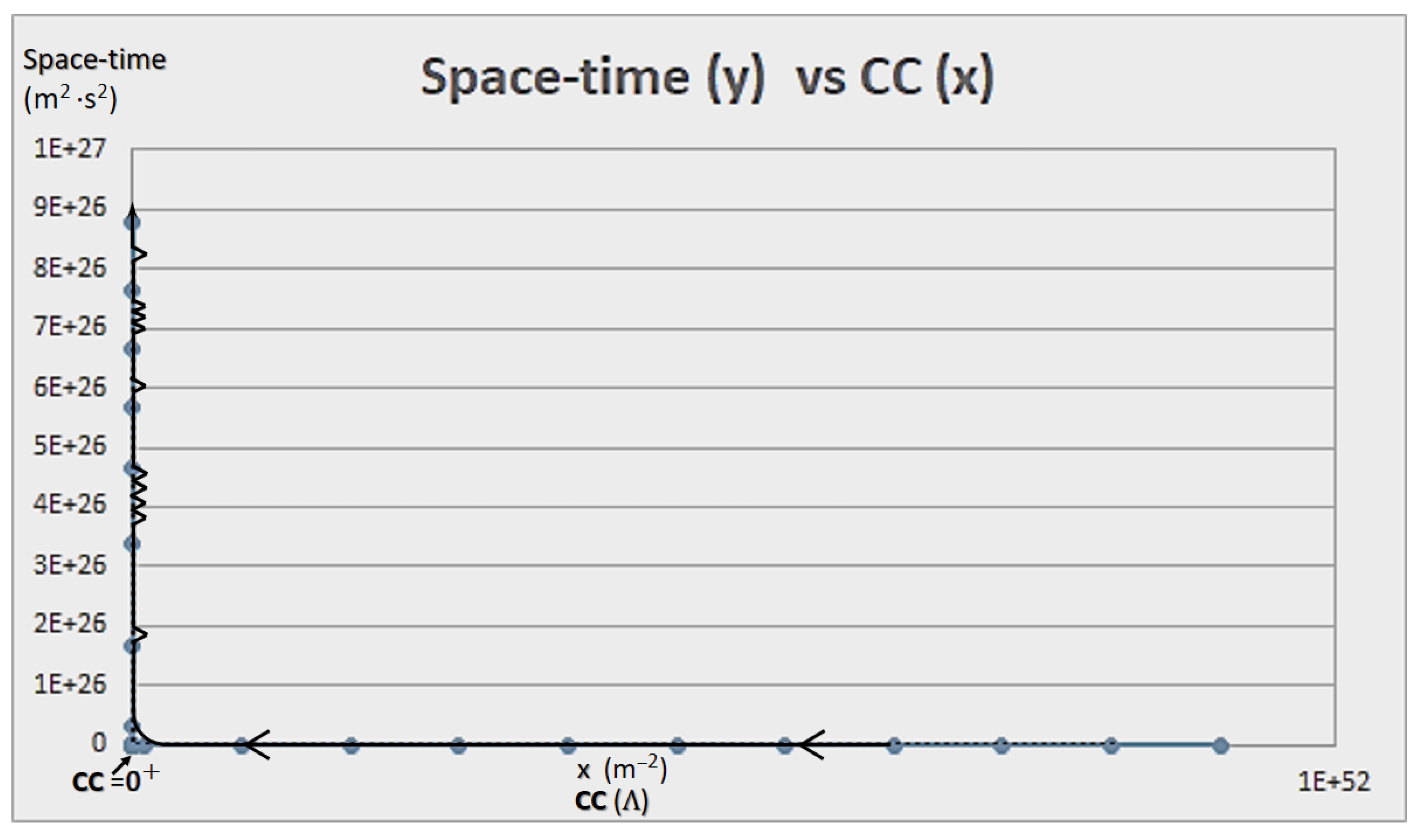

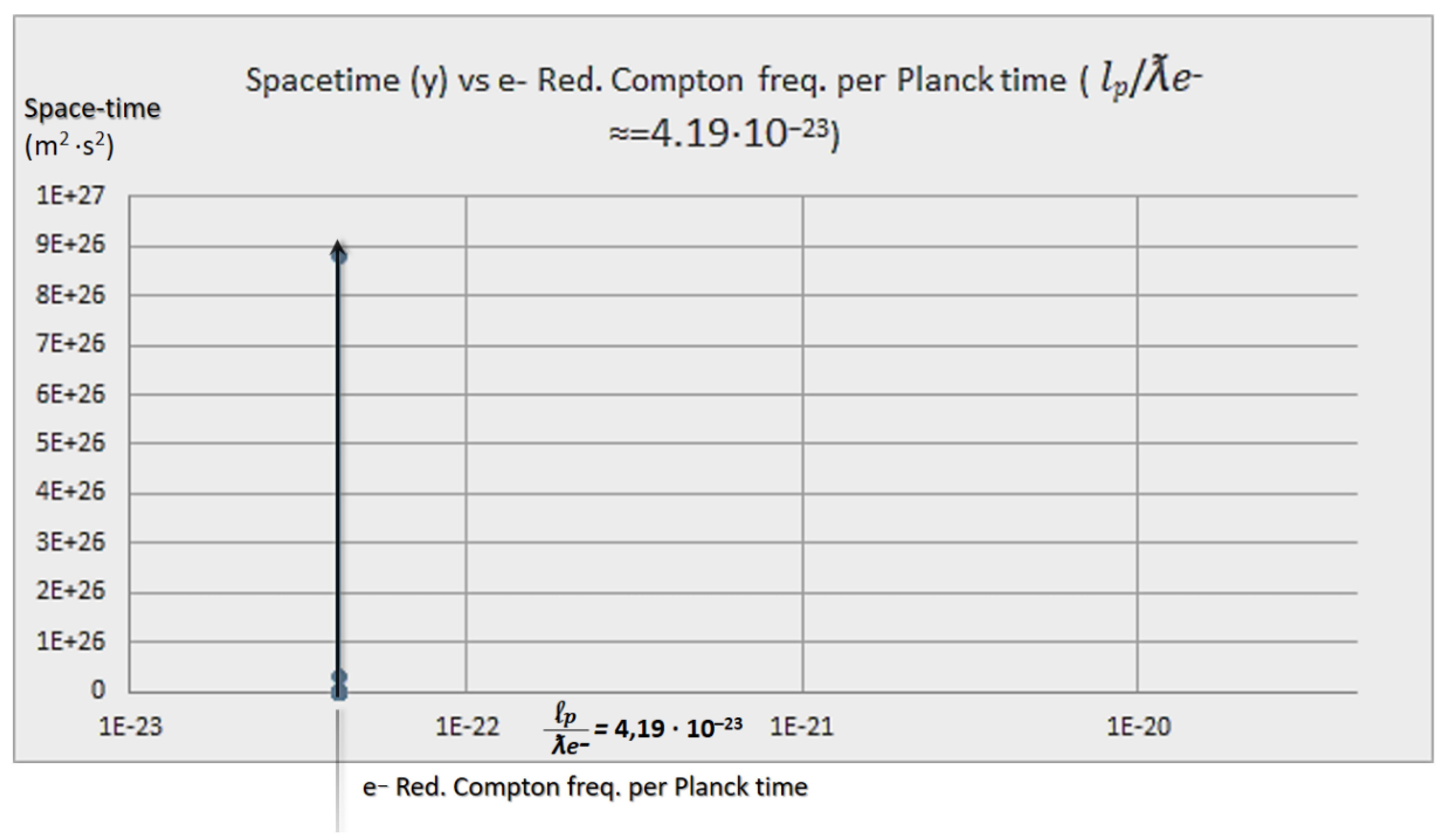

- Indeed, the CC (Λ) has units of m2. Therefore, as it can be regarded in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, as space increases, Λ decreases, which does not necessarily implies that time does as well, even though we use it to measure changes (whether +/- or null), and to relate distance to our framework, or if the rate of change (expansion), is stable, null, or steadily (or unsteadily) increasing, which perhaps to our understanding and at a cosmological scale has meaning, but at universal scale is a claim that, again, tends to the anthropomorphization of the universe and nature. As it was pointed out in an interestingly work [178]: “Newton did not express his law of gravitation in a way that explicitly included a constant G, its presence was implied as if it had a value equal to 1. It was not until 1873 that Cornu and Bailey explicitly introduced a symbol for the coupling constant in Newton’s law of gravity, in fact, they called it f. (The current designation G for the gravitational constant was only introduced sometime in the 1890s.)” in [178], p. 6, cfr. [211], p. 2.

-

Therefore, gravity might be setting the direction, and with the other fundamental variables (such as mass, entropy, and space) interaction, the “arrow of time” and our universe, as emergent properties.So, spacetime tells matter how to move, matter tells spacetime how to curve [195], and gravity tells the direction.

- A more inclusive approach was taken in regard the multiverse and the anthropic principle requirement. Applying Ockham’s razor one can ponder that it leads to a CCC—mirror-like—located sea-quark approach that allows one-universe—multiverse convergence (divergence actually). Anthropomorphization was rejected. For instance, Wang & Unruh [196] concluded “in this way, the large cosmological constant generated at small scales is hidden at observable scale and no fine-tuning of λB to the accuracy of 10−122 is needed”. Cosmological constant, fine-tuning, superdeterminism and symmetry-breaking may just be a spandrel, an outcome, instead of a cause or causes. Inflationary and Big Bang were assumed. Logical atomism was also rejected.

- Torsion was not treated but it seems both, plausible, and an increasingly wide approach that seems to properly solve the problem regarding “before the beginning”, boundary, or also called or related to Weyl Curvature Hypothesis [50,66,67,68,197,212], for instance to obtain renormalized energy–momentum tensors and thermodynamics of 2d black holes [212]. Time seems to lose meaning within a scale unified cosmos, cogitations such as a universe (with us within it) living in its very first second [69] or indeterminate time [50] p. 145, p. 159, p. 160, [68] p. 278, p. 296, [166] arisen. Anthropomorphization of time was also pointed and rejected. _ Entropy (space distribution, heat distribution, and radiation) and stochastic-like G‒mass‒energy equivalences seem to have more appropriated meaning and accuracy in scientific and physical terms.

- More research is required within this topic.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding sources

Data statement

Data References

| 1 | It is a clear and funny reference to anyons, as a potential long-range and long-seeked answer to some of the biggest challenges and paradoxes of QM, and the quantization of gravity, or the gravitization of the quantum. |

| 2 | Which may account for Dark Energy as M0 or μ2 = . |

| 3 | Either G, g or both can adjust their directions with ± as highlighted in Figure 1, according to Dirac [93], though while G may be in a sense probabilistic closely related to the background and the “arrow of time” perhaps becoming superdeterministic in the end, for g is a locally-bounded physical property. Over Mass as well can be applied but it could also have deeper implications as well. For more about ± in physics see [50, p. 146], [93,145]. |

| 4 | Noting that M was interpreted as a quantum field within the position in the gravitational potential, classical situation, so holding it up, before freeing it and without releasing it, one can substitute M as m2 · s2 ; one may recover the dimensions of mass from . This extra m might represent the quantum pressure. |

| 5 | It does not happen likewise, if mass is reduced to near Planck scale, or mass ∝ length reduction to Planck scale, since both, mass would be so reduced, as it would be the relation of the height (length) over the surface of contact (length2) to be time-governed (the acceleration s2 would take over emerging quantum effects such as superposition). |

References

- Feynman, R. P. (1985). QED. The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. (Alix G. Mautner Memorial Lectures). Princeton University Press.

- Weinberg, S. (2021). Foundations of modern physics. Cambridge University Press.

- Lagrange, J. L. (1772). Essai d’une nouvelle méthode pour résoudre le problême des trois corps. Académie Royale des Sciences.

- Lagrange, J. L. (1788). Mécanique analytique. Ed. Mme. Courcier.

- Du Châtelet, G. E. (1740). Institutions physiques de Madame la marquise du Châstellet. Ed. Prault fils.

- Du Châtelet, G. E. (1759). Principes mathématiques de la philosophie naturelle, par feue Madame la Marquise du Chastellet. Addendum, Tr. de Principia de Isaac Newton (1686). Ed. Desaint et Saillant, & Lambert.

- Newton, I. (1687). Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica. Ed. S. Pepys. Reg. Soc. Press.

- Newton, I. (1704). Opticks, or, a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections, and Colours of Light. Ed. Sam Smith & Benj Walford. Royal Society.

- Huygens, Ch. (1690). Traité de la Lumière: Où sont expliquées les causes de ce qui luy arrive dans la reflexion & dans la refraction. Ed. Pierre van der Aa.

- Leibniz, G. W. (1720). Lehr-Sätze über die Monadologie. Bey J. Meyers sel. witbe.

- Einstein, A. (1931). Cosmic religion: with other opinions and aphorism. Covici-Friede Inc.

- Einstein, A. (1915). Zür allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. Berlin, Sitzber, 47, 778-786.

- Einstein, A. (1916). Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Ann. der Phys., 49(7), 769–822. [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. (1901a). Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum. Ann. der Physik., 309(3), 553–562. [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. (1901b). Ueber die Elementarquanta der Materie und der Elektricität. Ann. der Physik, 309(3), 564-566. [CrossRef]

- Aspect, A., Clauser, J. F., & Zeilinger, A. (2022). Entangled states – from theory to technology. In: The Nobel Prize in Physics 2022. Royal Swedish Academy of Science. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2022/.

- Aspect, A., Dalibard, J., & Roger, G. (1982). Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Phys. Rev. Lett., 49(25), 1804-1807. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. (1975). The theory of local beables. In: Contribution to 6th Gift Seminar on Theoretical Physics: Quantum Field Theory; Dialectica, 39(1985), 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. (1981). Bertlmann‟s socks and the nature of reality. Journal de Physique Colloques, 42(C2), 41-62. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S, Clauser, J. F, Horne, M. A., & Shimony, A. (1985). An exchange on local beables. Dialectica, 39, 85-96. [CrossRef]

- Davisson, C. & Germer, L. H. (1927). The scattering of electrons by a single crystal of nickel. Nature, 119(2998), 558-560. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. (1926). An Undulatory Theory of the Mechanics of Atoms and Molecules. Phys. Rev., 28(6), 1049–1070. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. (1935a). Die gegenwärtige Situation in der Quantenmechanik. Die Naturwissen-schaften, 23(48), 807–812. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. (1935b). Discussion of Probability Relations between Separated Systems. Math. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc., 31(4), 555–563. [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. (1927). Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift fur Physik, 43, 172–198. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1905a). Zür elektrodynamik bewegter körper. Ann. der Physik, 322, 891-921. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A., Podolsky, B., & Rosen, N. (1935). Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev., 47(10), 777-780. [CrossRef]

- de Broglie, L. (1923). Waves and quanta. Nature, 112(2815), 540-540. [CrossRef]

- de Broglie, L. (1924) Recherches sur la théorie des quanta. (Tesis Doctoral), Masson, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Bohm, D. (1952). A Suggested Interpretation of the Quantum Theory in Terms of ’Hidden Variables’ I. Physical Review, 85(2), 166–179. [CrossRef]

- Young, T. (1804). The Bakerian Lecture. Experiments and calculations relative to physical optics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London, 94, 1–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/109575.

- Zeilinger, A. (1986). Testing Bell‟s inequalities with periodic switching. Phys. Lett. A, 118(1), 1-2. [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, A. (1924). Über die Möglichkeit einer Welt mit konstanter negativer Krümmung des Raumes. Zeitschrift für Physik, 21(1), 326-332. [CrossRef]

- Hubble, E. (1929). A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae. P.N.A.S., 15(3), 168-173. [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G. (1927). Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques. Annales de la Societe Scietifique de Bruxelles, 47, 49-59. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1927ASSB...47...49L//.

- Robertson, H. P. (1936). Kinematics and world structure III. Astrophysical Journal, 83, 257-271. [CrossRef]

- Vittorio, N. & Silk, J. (1984). Fine-scale anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background in a universe dominated by cold dark matter. Astrophysical Journal, Part 2 - Letters to the Editor, 285(2), L39-L44. [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. G. (1937). On Milne’s theory of world-structure. Proc. of the London Math. Soc., S2-42(1), 90-127. [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, F. (1933). Die Rotverschiebung von extragalaktischen Nebeln. Helvetica Physica Acta, 6, 110-127. [CrossRef]

- Banks, T., Fischler, W., Shenker, S. H., & Susskind, L. (1997). M theory as a matrix model: A conjecture. Phys. Rev. D, 55(8), 5112-5128. [CrossRef]

- Kaku, M. & Kikkawa, K. (1974). Field theory of relativistic strings. II. Loops and Pomerons. Phys. Rev. D, 10(6), 1823–1843. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. (1970). Structure of hadrons implied by duality. Phys. Rev. D, 1(4), 1182-1186. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (2010). Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. The Bodley Head.

- Gurzadyan, V. G. & Penrose, R. (2013). On CCC-predicted concentric low-variance circles in the CMB sky. Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 128, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Meissner, K. A. & Nurowski, P. (2017). Conformal transformations and the beginning of the Universe. Phys. Rev. D, 95(8), 084016. [CrossRef]

- An, D., Meissner, K. A., Nurowski, P., & Penrose, R. (2020). Apparent evidence for Hawking points in the CMB Sky. M.N.R.A.S., 495(3), 3403-3408. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (2020). Nobel Prize lecture on physics and chemistry. In: R. Penrose, R., Genzel, & A. Ghez, Black holes and the Milky Way’s darkest secret. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2020. Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. [https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2020/penrose/lecture/].

- Nurowski, P. (2021). Poincaré–Einstein approach to Penrose’s conformal cyclic cosmology. Class. Quantum Gravity 38(14), 145004. [CrossRef]

- Bodnia, E., Isenbaev, V., Colburn, K., Swearngin, J., & Bouwmeester, D. (2024). Conformal cyclic cosmology signatures and anomalies of the CMB sky. JCAP, 2024(9), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Bache, M. A. B. (2024a). Teoría X. Hacia la congruencia interdisciplinar entre universo y realidad(es). In: M. A. B. Bache & J. C. Rodríguez-Rodríguez (Eds.), Psicología, Complejidad y Sistemas (pp. 106-191). Dykinson.

- Tod, P. (2024). Conformal methods in mathematical cosmology. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A, 382, 20230043. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. & Smolin, L. (1988). Knot theory and quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters, 61(10), 1155-1158. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. & Smolin, L. (1995). Discreteness of area and volume in quantum gravity. Nuclear Physics B, 442(3), 593-619. [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, T. (1996). Anomaly-free formulation of non-perturbative, four-dimensional Lorentzian quantum gravity. Physics Letters B, 380(3-4), 257-264. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (1996). Black hole entropy from loop quantum gravity. Physical Review Letters, 77(16), 3288-3291. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. & Vidotto, F. (2014). Planck stars. International Journal of Modern Physics D, 23(12), 1442026. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S., Marcianò, A., & Tacchi, R. A. (2012). Towards a Loop Quantum Gravity and Yang–Mills unification. Physics Letters B, 716(2), 330-333. [CrossRef]

- Freidel, L. & Krasnov, K. (2008). A new spin foam model for 4d gravity. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 25(12), 125018. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press.

- Caldwell, R. R., Dave, R., & Steinhardt, P. J. (1998). Cosmological imprint of an energy component with general equation of state. Physical Review Letters, 80(8), 1582-1585. [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, P. J., Wang, L., & Zlatev, I. (1999). Cosmological tracking solutions. Physical Review D, 59(12), 123504. [CrossRef]

- Dave, R., Caldwell, R. R., & Steinhardt, P. J. (2002). Sensitivity of the cosmic microwave background anisotropy to initial conditions in quintessence cosmology. Physical Review D, 66(2), 023516. [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, G., Pathak, S. D., Sharma, M., & Wang, A. (2024). Distortion of quintessence dynamics by the Generalized Uncertainty Principle. Annals of Physics, 473, 169895. [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N., & Trnka, J. (2014). The amplituhedron. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2014(10), 1-33. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (2015). Palatial twistor theory and the twistor googly problem. Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. A: Math., Phys. and Eng. Sci., 373(2047), 20140237. [CrossRef]

- Waeber, S. & Yarom, A. (2021). Stochastic gravity and turbulence. JHEP, 2021(12), 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Bache, M. A. B. (2021). On the very origins of the Universe. An exacting mathematical verification. Spanish Government Intellectual Property Registry, Scientific Works. Registry entry 04/2021/4284.

- Bache, M. A. B. (2023a). Sobre los orígenes del universo: una comprobación meticulosa desde el punto de vista matemático en la 5ª dimensión. In: J. C. Rodríguez Rodríguez (Ed.), Psicología siglo XXI: una mirada amplia e integradora. Vol. 3 (pp. 252-308). Dykinson.

- Bache, M. A. B. (2023b). Grand Gravity and X-Theory. On the Unification of Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. US-China Education Review, 13(2), 60-74. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, L., Finn, K., & Turok, N. (2018). CPT-symmetric universe. Phys. Rev. Lett., 121(25), 251301. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1905b). Ist die Tragheit eines Korpers von sienem Energiegehalt Abhangig?. Ann. Phys, 323(13), 639-641. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1912). Einstein’s manuscript on the special theory of relativity. In: M. Klein, A. J. Kox., J. Renn, & R. Schulmann (Eds.), The collected papers of Albert Einstein Princeton, The Swiss years: writings 1912-1914, 1995 [1912] (pp. 9-108). Princeton University Press. https://einsteinpapers.press.princeton.edu/vol4-trans/61?ajax.

- ‘t Hooft, G. & Veltman, M. (1972). Regularization and renormalization of gauge fields. Nuclear Physics B, 44(1), 189-213. [CrossRef]

- ‘t Hooft, G. & Veltman, M. (1974). One-loop divergencies in the theory of gravitation. Annales de l’institut Henri Poincaré. Section A, Physique Théorique, 20(1), 69-94. http://eudml.org/doc/75797.

- Deser, S., Tsao, H. S., & Van Nieuwenhuizen, P. (1974). One-loop divergences of the Einstein-Yang-Mills system. Physical Review D, 10(10), 3337. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. (1972). Gravitation and cosmology. John Wiley.

- ‘t Hooft, G. (2005). The conceptual basis of Quantum Field Theory. Utrecht University Open. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/22670.

- Einstein, A. (1927). Einstein contributions to the 5th Solvay Conference. In: H. Lorentz (Ed.), Electrons et Photons, 5th Solvay Conference, 24 to 29 October 1927.

- Böhr, N. (1949). Discussion with Einstein on epistemological problems in atomic physics. In: P. A. Schilpp. (Ed.), Albert Einstein: philosopher-scientist (pp. 200-241). The Library of Living Philosophers.

- L’Huillier, A., Agostini, P., & Krausz, F. (2023). Electrons as pulses of light. In: The Nobel Prize in Physics 2023. Royal Swedish Academy of Science.

- Bekenstein, J. & Milgrom, M. (1984). Does the missing mass problem signal the breakdown of Newtonian gravity?. Astr. J., 286, 7-14. [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. & Bekenstein, J. (1987). The modified Newtonian dynamics as an alternative to hidden matter. In: Symposium-International astronomical union, 117, 319-333. Cambridge University Press.

- Milgrom, M. (2023). Generalizations of quasilinear MOND. Phys. Rev. D, 108(8), 084005. [CrossRef]

- Chae, K. H. & Milgrom, M. (2022). Numerical Solutions of the External Field Effect on the Radial Acceleration in Disk Galaxies. Astr. J., 928(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, B., Johnson, B. D., Tacchella, S., Eisenstein, D. J., Hainline, K., Arribas, S., ... & Witstok, J. (2024). Earliest Galaxies in the JADES Origins Field: Luminosity Function and Cosmic Star Formation Rate Density 300 Myr after the Big Bang. Astr. J., 970(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Lovell, C. C., Harrison, I., Harikane, Y., Tacchella, S., & Wilkins, S. M. (2023). Extreme value statistics of the halo and stellar mass distributions at high redshift: are JWST results in tension with ΛCDM?. M.N.R.A.S., 518(2), 2511-2520. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M., Oesch, P. A., Elbaz, D., Bing, L., Nelson, E. J., Weibel, A., ... & Wyithe, J. S. B. (2024). Accelerated formation of ultra-massive galaxies in the first billion years. Nature, 635(8038), 311-315. [CrossRef]

- Carniani, S., Hainline, K., D’Eugenio, F., Eisenstein, D. J., Jakobsen, P., Witstok, J., ... & Willmer, C. N. (2024). Spectroscopic confirmation of two luminous galaxies at a redshift of 14. Nature, 633(8029), 318-322. [CrossRef]

- Primack, J. R. (2024). Galaxy Formation in ΛCDM Cosmology. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 74, 173-206. [CrossRef]

- Arrabal Haro, P., Dickinson, M., Finkelstein, S. L., Kartaltepe, J. S., Donnan, C. T., Burgarella, D., ... & Zavala, J. A. (2023). Confirmation and refutation of very luminous galaxies in the early Universe. Nature, 622(7984), 707-711. [CrossRef]

- [91] Carniani, S. & Hainline, K. (2024). NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope finds most distant known galaxy. https://blogs.nasa.gov/webb/2024/05/30/nasas-james-webb-space-telescope-finds-most-distant-known-galaxy/ [Accessed 16/01/2025].

- Gupta, R. P. (2023). JWST early Universe observations and ΛCDM cosmology. M.N.R.A.S., 524(3), 3385-3395. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1938). A new basis for cosmology. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 165(921), 199-208. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. P. (2022). Effect of evolving physical constants on type Ia supernova luminosity. M.N.R.A.S., 511(3), 4238-4250. [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, V. N. (1994). Fundamental physical constants and their stability: A review. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 33, 1569-1579. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. P. (2023a). Constraining Co-Varying Coupling Constants from Globular Cluster Age. Universe, 9(2), 70. [CrossRef]

- McQuinn, K. B., Newman, M. J., Skillman, E. D., Telford, O. G., Brooks, A., Adams, E. A., ... & Goldman, S. R. (2024). The Ancient Star Formation History of the Extremely Low-mass Galaxy Leo P: An Emerging Trend of a Post-reionization Pause in Star Formation. Astr. J., 976(1), 60. [CrossRef]

- Slob, M., Kriek, M., Beverage, A. G., Suess, K. A., Barro, G., Bezanson, R., ... & Weisz, D. R. (2024). The JWST-SUSPENSE Ultradeep Spectroscopic Program: Survey Overview and Star-Formation Histories of Quiescent Galaxies at 1< z< 3. Astr. J., 973(2), 131. [CrossRef]

- Birrell, J., Yang, C. T., Chen, P., & Rafelski, J. (2014). Relic neutrinos: Physically consistent treatment of effective number of neutrinos and neutrino mass. Physical Review D, 89(2), 023008. [CrossRef]

- Rafelski, J., Birrell, J., Steinmetz, A., & Yang, C. T. (2023). A short survey of matter-antimatter evolution in the primordial universe. Universe, 9(7), 309. [CrossRef]

- Rafelski, J., Birrell, J., Grayson, Ch., Steinmetz, A., Yang, Ch. T. (2024). Quarks to Cosmos: Particles and Plasma in Cosmological evolution. In: XVI Quark Confinement and the Hadron Spectrum Conference, 19 to 24 August 2024.

- Yung, L. A., Somerville, R. S., Finkelstein, S. L., Wilkins, S. M., & Gardner, J. P. (2024). Are the ultra-high-redshift galaxies at z> 10 surprising in the context of standard galaxy formation models?. M.N.R.A.S., 527(3), 5929-5948. [CrossRef]

- Menci, N., Castellano, M., Santini, P., Merlin, E., Fontana, A., & Shankar, F. (2022). High-redshift galaxies from early JWST observations: constraints on dark energy models. Astr. J. Lett., 938(1), L5. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A. C., Teklu, A. F., Dolag, K., & Remus, R. S. (2023). ΛCDM with baryons versus MOND: The time evolution of the universal acceleration scale in the Magneticum simulations. M.R.N.A.S. 518(1), 257-269. [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R., Falomo, R., & Treves, A. (2022). On the orbital velocity of isolated galaxy pairs: II accurate MOND predictions. M.N.R.A.S., 512(1), 544-547. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B. P., Suntzeff, N. B., Phillips, M. M., Schommer, R. A., Clocchiatti, A., Kirshner, R. P., … & Riess, A. G. (1998). The high-Z supernova search: Measuring cosmic deceleration and global curvature of the universe using type Ia supernovae. Astr. J., 507(1), 46-63. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S., Aldering, G., Goldhaber, G., Knop, R. A., Nugent, P., Castro, P. G., ... & Supernova Cosmology Project. (1999). Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high-redshift supernovae. Astr. J., 517(2), 565-586. [CrossRef]

- Riess, A. G., Schmidt, B. P., & Perlmutter, S. (2011). The accelerating universe. Nobel Prize in Physics „for the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the Universe through observations of distant supernovae”. In: The Nobel Prize in Physics 2011. Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2011/summary/ [https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/advanced-physicsprize2011.pdf].

- Carroll, S. M. (2001). The cosmological constant. Living Reviews in Relativity, 4(1), 1-56. [CrossRef]

- Hoavo, H. O. V. A. (2020). Accelerating universe with decreasing gravitational constant. Journal of King Saud University-Science, 32(2), 1459-1463. [CrossRef]

- Babourova, O. V. & Frolov, B. N. (2020). On the exponential decrease of the “cosmological constant” in the super-early Universe. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1557(1), 012011. [CrossRef]

- Foundational Aspects of Dark Energy (FADE) Collaboration, Bernardo, H., Bose, B., Franzmann, G., Hagstotz, S., He, Y., Litsa, A., & Niedermann, F. (2023). Modified Gravity Approaches to the Cosmological Constant Problem. Universe, 9(2), 63. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. (1989). The cosmological constant problem. Reviews of Modern Physics, 61(1), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Zel’Dovich, Y. B. (1968). The cosmological constant and the theory of elementary particles. Soviet Physics Uspekhi, 11(3), 381. [Zel’dovich, Y. B. (1967). JETP Lett. 6, 316]. [CrossRef]

- Kaloper, N. & Westphal, A. (2022). Quantum-mechanical mechanism for reducing the cosmological constant. Physical Review D, 106(10), L101701. [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. (2007). The cosmological constant. General Relativity and Gravitation. 40, 607-637. [CrossRef]

- Preskill, J., Wise, M., Wilczek, F. (1983). Cosmology of the invisible axion. Physics Letters B, 120(1–3), 127-132. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Ilie, C., & Freese, K. (2024). Detectability of Supermassive Dark Stars with the Roman Space Telescope. Astr. J., 965(2), 121. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G. W., Lei, L., Wang, Y. Z., Wang, B., Wang, Y. Y., Chen, C., ... & Fan, Y. Z. (2024). Rapidly growing primordial black holes as seeds of the massive high-redshift JWST Galaxies. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy, 67(10), 109512. [CrossRef]

- Griest, K. (1993). The search for the dark matter: WIMPs and MACHOs. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 688(1), 390-407. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y., Wang, Z., Tao, Y., Abdukerim, A., Bo, Z., Chen, W., ... & (PandaX-4T Collaboration). (2021). Dark matter search results from the PandaX-4T commissioning run. Physical Review Letters, 127(26), 261802. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D. E., Krnjaic, G. Z., Rehermann, K. R., & Wells, C. M. (2010). Atomic dark matter. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2010(05), 021. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S., Barron, J., Curtin, D., & Tsai, Y. (2023). Precision cosmological constraints on atomic dark matter. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2023(10), 1-37. [CrossRef]

- Fermi, E. (1934). Versuch einer Theorie der β-Strahlen. I. Zeitschrift für Physik A, 88(3–4), 161–177. [CrossRef]

- Cowan Jr, C. L., Reines, F., Harrison, F. B., Kruse, H. W., & McGuire, A. D. (1956). Detection of the free neutrino: a confirmation. Science, 124(3212), 103-104. [CrossRef]

- Boyarsky, A., Drewes, M., Lasserre, T., Mertens, S., & Ruchayskiy, O. (2019). Sterile neutrino dark matter. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics, 104, 1-45. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, L. M. (2012). A universe from nothing: Why there is something rather than nothing. Simon and Schuster.

- Gell-Mann, M. (1964). A Schematic Model of Baryons and Mesons. Physics Letters, 8(3), 214–215. [CrossRef]

- Zweig, G. (1964). An SU3 model for strong interaction symmetry and its breaking. In: D. Lichtenberg & S. Rosen. (Eds.), Developments in the Quark Theory of Hadrons. Vol. 1 (pp. 22-101). Nonantum, Mass., Hadronic Press. [CrossRef]

- Bjørken, B. J. & Glashow, S. L. (1964). Elementary particles and SU (4). Physics Letters, 11(3), 255-257. [CrossRef]

- van Hove, L. (1987). Theoretical prediction of a new state of matter, the „Quark-Gluon plasma” (also called „Quark Matter”). In: Proceedings of the XVII international symposium on multiparticle dynamics, 20(10), 20030911. https://cds.cern.ch/record/183417?ln=es.

- Brodsky, S. J., Hoyer, P., Peterson, C., & Sakai, N. (1980). The intrinsic charm of the proton. Physics Letters B, 93(4), 451-455. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. A. (1978). The “past” and the “delayed-choice” double-slit experiment. In: A. R. Marlow (Ed.), Mathematical foundations of quantum theory (pp. 9-48). Academic Press.

- Vedovato, F., Agnesi, C., Schiavon, M., Dequal, D., Calderaro, L., Tomasin, M., … & Villoresi, P. (2017). Extending Wheeler’s delayed-choice experiment to space. Science Advances, 3(10), e1701180. [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S., & Palmer, T. (2020). Rethinking superdeterminism. Frontiers in Physics, 8, 139. [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R. P. (1948). Space-Time approach to non-relativistic Quantum Mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 20(2), 367–387. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W. R. (1834). On a general method in dynamics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc., 124, 247–308. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1933). Theory of electrons and positrons. In: The Nobel Prize in Physics 1933. Royal Swedish Academy of Science. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1933/dirac/lecture/.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1975). The story of the positron. In: The Development of Quantum Mechanics, Accademia dei Lincei, Roma (pp. 11). www.lincei.it/it/videoteca/15041975-story-positron-video https://youtu.be/1T_Nv482jFI [Accessed 18/01/2025].

- Bentley, R. (1693). Original letter from Richard Bentley to Newton, Feb. 18. 1693. In: The Newton Project, 189.R.4.47, ff. 3-4, 2007. Trinity College Library, Cambridge, UK. https://www.newtonproject.ox.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00257 [Accessed 12/01/2025].

- Newton, I. (1693). Original letter from Isaac Newton to Richard Bentley, Feb. 25. 1693. In: The Newton Project 189.R.4.47, ff. 7-8, 2007. Trinity College Library, Cambridge, UK https://www.newtonproject.ox.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00258 [Accessed 17/01/2025].

- Russell, B. (1924). Logical Atomism. In: The Philosophy of Logical Atomism (2009). Routledge.

- Klein, O. (1927). Elektrodynamik und wellenmechanik vom standpunkt des korrespondenzprinzips. Zeitschrift für Physik A, Hadrons and nuclei, 41, 407–442. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, W. (1926). Der comptoneffekt nach der schrödingerschen theorie. Zeitschrift für Physik, 40, 117-133. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1931). Quantised singularities in the electromagnetic field. Proc. of the Roy. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, Cont. Pap. Math. and Phys. Char., 133(821), 60-72. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. D. (1933). The Positive Electron. Phys. Rev. 43, 491-494. [CrossRef]

- Bose. (1924). Plancks gesetz und lichtquantenhypothese. Zeitschrift für Physik, 26(1), 178-181. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. (1924). Quantentheorie des einatomigen idealen Gases II, Sitz. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss., 1, 3-14.

- Hanada, M., Shimada, H., & Wintergerst, N. (2021). Color confinement and Bose-Einstein condensation. JHEP, 2021(8), 39. [CrossRef]

- Shieh, T. T. (2015). From gradient theory of phase transition to a generalized minimal interface problem with a contact energy. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems, 36(5), 2729-2755. [CrossRef]

- Wieman, C., Ketterle, W., & Cornell, E. (2001). New state of matter revealed: Bose-Einstein Condensate. In: The Nobel Prize in Physics 2001. Royal Swedish Academy of Science. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2001/.

- Sen, S. & Gangopadhyay, S. (2024). Probing the quantum nature of gravity using a Bose-Einstein condensate. Physical Review D, 110(2), 026014. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K. T. (2024). Bose and the angular momentum of the photon. American Journal of Physics, 92(9), 711-716. [CrossRef]

- Vlasov, A. A. (1968). The Vibrational Properties of an Electron Gas. Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 10(6), 721–733. [CrossRef]

- Merrill, H. J. & Webb, H. W. (1939). Electron scattering and plasma oscillations. Physical Review. 55(12), 1191-1198. [CrossRef]

- Lossev, A. & Novikov, I. D. (1992). The Jinn of the time machine: non-trivial selfconsistent solutions. Class. Quantum Grav., 9(10), 2309-2321. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1979). Singularities and time-asymmetry. In: S. Hawking & W. Israel (Eds.), General Relativity : An Einstein Centenary Survey (pp. 581-638). Cambridge University Press.

- Prigogine, I., & Nicolis, G. (1967). On symmetry-breaking instabilities in dissipative systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 46(9), 3542-3550.

- Prigogine, I. (1989). Thermodynamics and cosmology. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 28, 927-933.

- Prigogine, I. & Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos: The evolutionary paradigm and the physical sciences. Bantam Books.

- Kosterlitz, J. M., Haldane, F. D. M., & Thouless, D. J. (2016). Nobel Prize “for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter”. In: The Nobel Prize in Physics 2016. Royal Swedish Academy of Science. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2016/summary/.

- Joos, E. & Zeh, H. D. (1985). The emergence of classical properties through interaction with the environment. Zeitschrift für Physik B Condensed Matter, 59, 223-243. [CrossRef]

- Haug, E. G. (2023). Different mass definitions and their pluses and minuses related to gravity. Foundations, 3(2), 199-219. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. (1977). Time, Structure and Fluctuations. Nobel Lecture. In: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1977. Royal Swedish Academy of Science. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1977/prigogine/lecture/.

- Carter, B. (1974). Large number coincidences and the anthropic principle in cosmology. In: M. S. Longair (Ed.), Confrontation of Cosmological Theories with Observational Data (pp. 291–298). International Astronomical Union.

- Bache, M. A. B. (2024b). Universo frente a realidad. Revisión de la aplicación del principio antrópico-Del nonsequitur de Copenhague a la selección natural. In: IV CIISEP, 25 to 27 September 2024 (AIISEP). https://youtu.be/KqzJcYYvlVY.

- Zurek, W. H. (2009). Quantum darwinism. Nature Physics, 5(3), 181-188. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (2007). The Road to Reality. Knopf Doubleday.

- Zurek, W. H. (2003). Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics. 75(3), 715-775. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1996). On Gravity’s role in Quantum State Reduction. Gen. Rel. and Grav., 28, 581-600. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, K. J. (2022). Revealing a trans-Planckian world solves the cosmological constant problem. Progress of Theoretical and Experimental Physics, 2022(10), 103E02. [CrossRef]

- Everett III, H. (1957). Relative state formulation of quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics, 29(3), 454-462. [CrossRef]

- Everett III, H., Wheeler, J. A., DeWitt, B. S., Cooper, L. N., Van Vechten, D., & Graham, N. (1973). The Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. In: B. S. DeWitt & G. R. Neill (Eds.), Princeton Series in Physics. Princeton University Press.

- Blume-Kohout, R. & Zurek, W. H. (2006). Quantum Darwinism: Entanglement, branches, and the emergent classicality of redundantly stored quantum information. Physical Review A—Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics, 73(6), 062310. [CrossRef]

- Blume-Kohout, R., & Zurek, W. H. (2008). Quantum Darwinism in quantum Brownian motion. Physical Review Letters, 101(24), 240405. [CrossRef]

- Unden, T. K., Louzon, D., Zwolak, M., Zurek, W. H., & Jelezko, F. (2019). Revealing the emergence of classicality using nitrogen-vacancy centers. Physical Review Letters, 123(14), 140402. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M., Rams, M. M., Dziarmaga, J., Heyl, M., & Zurek, W. H. (2022). Quantum phase transition dynamics in the two-dimensional transverse-field Ising model. Science Advances, 8(37), eabl6850. [CrossRef]

- Matsas, G. E., Pleitez, V., Saa, A., & Vanzella, D. A. (2024). The number of fundamental constants from a spacetime-based perspective. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 22594. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. C. (1878). A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, (Clarendon, 1878), Reprinted by Dover, New York [1954].

- Gödel, K. (1931). Über formal unentschedibare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme, I. Monatsh. Math. Phys., 38, 173-198. [CrossRef]

- Wigner, E. P. (1960). The unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in the natural sciences. Richard courant lecture in mathematical sciences delivered at New York University, May 11, 1959. Communications on Pure and Applied Science, 13(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. J. (1963). The independence of the continuum hypothesis. P.N.A.S., 50(6), 1143-1148. [CrossRef]

- Bache, M. A. B. & Hernández-Contreras, J. (2025). Do animals share space? An explanation to Zeno’s paradox (of motion). arXiv preprint. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379-423. [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. (1877). Über die Beziehung zwischen dem zweiten Hauptsatze der mechanischen Wärmetheorie und der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung, respektive den Sätzen über das Wärmegleichgewicht. Sitzungsber. Kais. Akad. Wiss. Wien Math. Naturwiss. Class., 76, 373-435.

- Leff, H. S. (1996). Thermodynamic entropy: The spreading and sharing of energy. American Journal of Physics, 64(10), 1261-1271. [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, (1927). Thermodynamik quantummechanischer gesamheiten. Gott. Nach., 1(1927), 273-291. http://eudml.org/doc/59231.

- Sharp, K. & Matschinsky, F. (2015). Translation of Ludwig Boltzmann’s paper “On the Relationship between the Second Fundamental Theorem of the Mechanical Theory of Heat and Probability Calculations Regarding the Conditions for Thermal Equilibrium” Sitzung. Kaiser. Akad. Wissensch. Mathem.-Natur. Class., Abt. II, LXXVI 1877, pp 373-435 (Wien. Ber. 1877, 76, 373-435). Reprinted in Wiss. Abhandlungen, Vol. II, reprint 42, p. 164-223, Barth, Leipzig, 1909. Entropy, 17(4), 1971-2009. [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. (1884). Ableitung des Stefanschen Gesetzes, betreffend die Abhängigkeit der Wärmestrahlung von der Temperatur aus der elektromagnetischen Lichttheorie. Annalen der Physik, 258(6), 291–294. [CrossRef]

- Carathéodory, C. (1909). Untersuchungen über die Grundlagen der Thermodynamik. Math. Ann., 67(3), 355–386. [CrossRef]

- Clausius, R. (1854). Über eine veränderte Form des zweiten Hauptsatzes der mechanischen Wärmetheorie. Annalen der Physik, 169(12), 481-506. [CrossRef]

- Zeh, H. D. (1989). The direction of time. Springer-Verlag.

- Leinweber, D. B. (2000). Visualizations of the QCD vacuum. arXiv preprint. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. A. (1955). Geons. Physical Review, 97(2), 511-536. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. A. & Ford, K. (2000). Geons, black holes, and quantum foam: A life in physics. WW Norton & Company.

- Wang, Q. & Unruh, W. G. (2020). Vacuum fluctuation, microcyclic universes, and the cosmological constant problem. Physical Review D, 102(2), 023537. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y. J. (2019). Entropy and Gravitation—From Black Hole Computers to Dark Energy and Dark Matter. Entropy, 21(11), 1035. [CrossRef]

- Styer, D. F. (2000). Insight into entropy. American Journal of Physics, 68(12), 1090-1096. [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I. & Galaktionov, E. (2021). Regular electrically charged objects in Nonlinear Electrodynamics coupled to Gravity. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2103(1), 012078). [CrossRef]

- Agazie, G., Anumarlapudi, A., Archibald, A. M., Arzoumanian, Z., Baker, P. T., Bécsy, B., ... & NANOGrav Collaboration. (2023). The NANOGrav 15 yr data set: Evidence for a gravitational-wave background. Astroph. J. Lett., 951(1), L8. [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I. (2015). Electromagnetic source for the Kerr–Newman geometry. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 24(14), 1550094. [CrossRef]

- Dymnikova, I. (2015). Elementary Superconductivity in Nonlinear Electrodynamics Coupled to Gravity. Journal of Gravity, 2015(1), 904171. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1965). Gravitational collapse and space-time singularities. Phys. Rev. Lett., 14(3), 57–59. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, B., Gustafson, G., & Peterson, C. (1977). The relationship between the meson, baryon, photon and quark fragmentation distributions. Physics Letters B, 69(2), 221-224. [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfest, P. (1909). Gleichförmige rotation starrer körper und relativitätstheorie. Physikalische Zeitschrift, 10, 918. https://www.lorentz.leidenuniv.nl/IL-publications/sources/Ehrenfest_09d.pdf [Accessed 29/01/2025].

- Grøn, Ø. (1979). Relativistic description of a rotating disk with angular acceleration. Foundations of Physics, 9(5), 353–369. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J. (2024). Ehrenfest paradox: A careful examination. American Journal of Physics, 92(2), 140–145. [CrossRef]

- North, J. S., Wikle, C. K., & Schliep, E. M. (2023). A Review of Data-Driven Discovery for Dynamic Systems. Int. Stat. Rev., 91(3), 464-492. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wagner, N., & Rondinelli, J. M. (2019). Symbolic regression in materials science. MRS Communications, 9(3), 793–805. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. (1968). Twistor quantisation and curved space-time. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 1(1), 61-99. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T. & Speake, C. (2014). The Newtonian constant of gravitation - a constant too difficult to measure? An introduction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A, 372(2026), 20140253. [CrossRef]

- Paci, G. & Zanusso, O. (2025). Weyl cohomology and the conformal anomaly in the presence of torsion. Annals of Physics, 473, 169877. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).