1. Introduction

In the past decade, Industry 4.0 and Digitalization as its fundament [

1], shaped the development of the industry worldwide [

2]. Based on the comprehensive network of and between all industrial machines and devices it offers opportunities for real-time monitoring of all relevant process parameters. The available and collected data in turn forms the basis for shorter reaction times, a deeper process understanding, more resilient and efficient processes and, in the long term, for the self-regulation of processes if the target parameters are known and specified [

3]. So far, large companies in particular have made proactive progress in this area of technology in recent years due to the financial and employee resources available [

4]. Nevertheless, 13 years after the official launch of the Industry 4.0 [

5], many small and medium-sized companies (SME) are still struggling with the implementation of Industry 4.0 solutions. The reasons for this are manifold and include (in the case of Germany) an unclear cost-benefit ratio, a lack of understanding of what to do with the data, limited human and financial resources (the latter drastically increases the operational risk in the event of misinvestment), a lack of Industry 4.0 development strategies, historically grown asset portfolios that are difficult to link together as well as a significant proportion of manually performed operations [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. According to the German Federal Statistical Office, SMEs account for more than 99% of all companies in Germany, employ 55% of all workers, train around 70% of the next generation of employees and contribute around 42% of gross value added [

12]. SMEs are therefore an important pillar of the national and international economy. It is crucial that these companies are not left behind in the future development of Industry 4.0 (also in the direction of Manufacturing X [

13]), but are instead put in a position where they are able to realise their full potential [

14].

At the centre of many industrial sectors (in which SMEs are also active) are processes that require precise thermal process control. According to the International Energy Agency, 50 % of the total heat generated is used for industrial processes [

15]. For efficient, resilient and therefore reproducible process control, precise temperature measurement and monitoring are essential [

16]. Typical sectors to which this applies include the chemical and pharmaceutical industries (e.g. pyrolysis and synthesis) [

17], metal, glass and ceramic processing (e.g. furnace monitoring) [

18,

19,

20] or food processing (e.g. drying processes) [

21,

22], among others. Both, the Industry 4.0-compliant recording of temperature as well as of the energy consumption, has high potential for SMEs acting in this sectors to begin with the realisation of internal industry-4.0-steps, offering benefits already in the short-range such as process transparency and process data mining [

23,

24,

25].

Due to the cross-sectoral importance of these two measured variables, targeted technological and needs-based solutions for recording and utilising them can help to open the door to the technology field of Industry 4.0 for a large number of SME companies. Therefore, based on a compact description of the casting production on the example of the aluminium melt processing, this work presents a comprehensive, universally applicable concept for the digital real-time recording, storage and visualisation of process temperatures and their energy consumption. After that, the implementation and testing of this concept is carried out using the example of foundry technology (aluminium processing) on an industrial scale, representative of other comparable applications.

2. Theory

2.1. Digitalisation and Industry 4.0

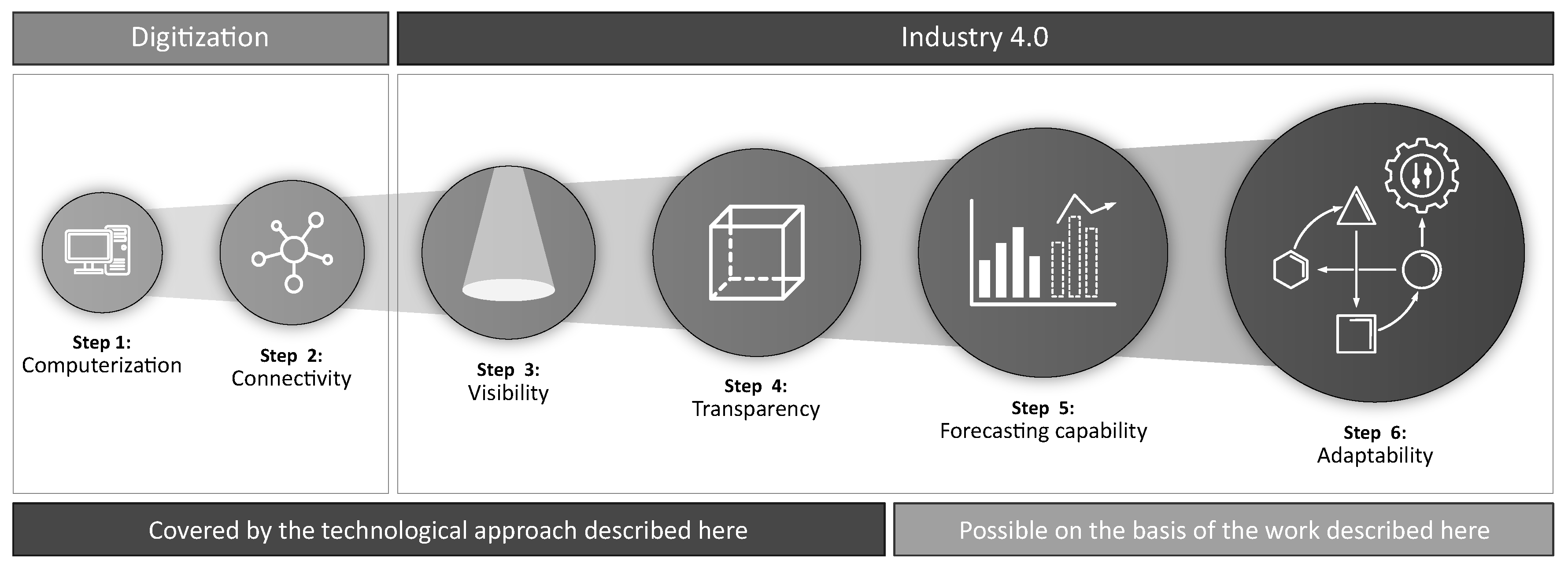

In order to ensure a uniform starting point at the beginning, it should be briefly explained once again where the boundaries of digitalisation and Industry 4.0 lie. In 2016, the FIR e.V. at RWTH Aachen University first published a clear infographic [

1] that illustrates this development and, based on this, is shown in

Figure 1 in its basic course. According to this, the Industry 4.0 development path consists of six stages, the first two of which are assigned to digitalisation and comprise the steps of computerisation (1) and connectivity (2). The transition from connectivity (2) to visibility (3) and transparency (4) of measurement data marks the entry into the field of Industry 4.0. The last two steps, predictability (5) and adaptability (6 - self-optimisation), are not considered further in the context of the work presented here, but can potentially be covered by the following concept.

If manufacturing companies are enabled to permanently record and visualise their processes and process data in real time, the doors to Industry 4.0 are opened for these companies and a robust (data) basis is created on which all further development steps can be built. The computerisation and connectivity of the digitalisation phase are automatically covered.

2.2. Fundamentals of Casting Production

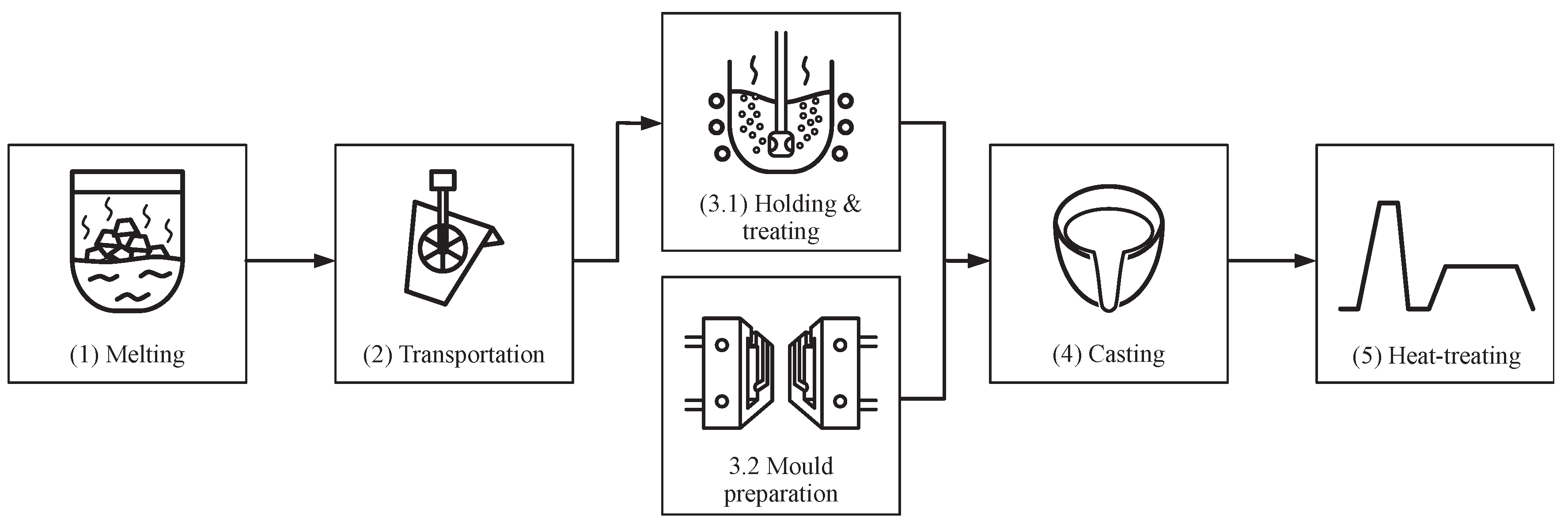

The production of aluminium castings - illustrated in simplified form in

Figure 2 - generally begins with the melting of ingots and recycled material in melting furnaces (1). The material melted down there is poured into transport ladles (2), which are used to transport the molten material to the casting stations. There, the molten material is transferred to holding furnaces (3.1). In order to remove the impurities from the melt, which are present from contaminated ingots and circulation material as well as due to the reaction of the aluminium melt with the air, the melt is cleaned with the aid of salts and foundry degassing units (impellers). Depending on the alloy, grain refinement and refining is carried out during and/or after this to reduce the grain size and refine the silicon phases for better mechanical properties of the cast parts. This is followed by quality testing and assurance measures such as density index testing and spectroscopic analyses of the composition, which may lead to steps for renewed melt treatment and the addition of alloying elements. At the same time, the casting mould is prepared (3.2). In the case of the production of aluminium castings, these are usually permanent steel moulds (‘dies’). This is preheated to a temperature that ensures complete mould filling (avoiding cold running), but low enough to ensure rapid solidification, resulting in cast parts with a fine structure and therefore good mechanical properties. Coating is also applied to the mould cavity, i.e. the negative of the casting. This serves to improve the removal of the casting by avoiding direct contact between the steel mould and the molten aluminium. The coating also improves the flow properties and influences the heat transfer during solidification. The heat balance of the casting mould and melt directly influences the solidification behaviour of the melt and therefore the final mechanical properties of the manufactured casting. Once the melt and mould have reached the correct temperature, casting takes place (robot, cobot, skilled foundry worker) (4). After complete solidification, the casting is removed from the mould and usually cools down at room temperature. After the riser and gating system have been separated, a three-stage heat treatment (5) consisting of solution annealing, quenching and (warm) ageing is carried out in the mould or at least in the case of castings that will later be subjected to thermo-mechanical stress. Precise temperature control during all process steps is essential for the reproducible adjustment of the mechanical properties of high-quality, defect-free castings [

26,

27].

The importance of stable temperature levels for the production of high-quality and reproducible castings is clear from the above descriptions. In many SME foundries, these two factors are depending on the experience and expertise of the employee and do not allow objective assurance and traceability after the production processes. Against the backdrop of an increasing shortage of skilled labour and the growing number of lateral entrants who often lack awareness of the importance of casting production-specific temperature levels, which can result in fluctuating production conditions, the need for real-time process transparency and the safeguarding of relevant production criteria is growing. Industry 4.0-compliant technologies for sensing temperatures can make this possible.

2.3. Foundry 4.0 Developments

Since the beginning of Industry 4.0, numerous corresponding developments have also taken place in the field of foundry technology.

Table 1 is intended to provide an overview of some of these developments academically published, without claiming to be complete. There are also numerous publications on developments in the field of Industry 4.0 on the websites of manufacturers of casting technology equipment and in relevant foundry industry media, which will not be discussed further here.

2.4. Information Technology Fundamentals

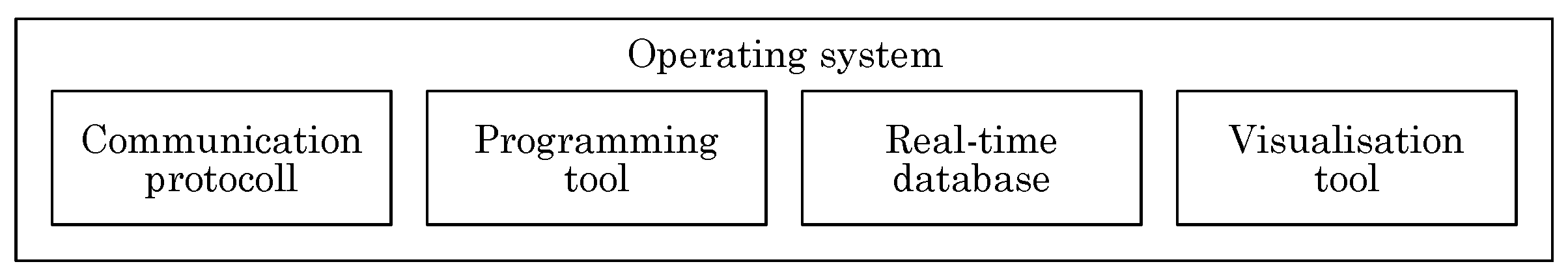

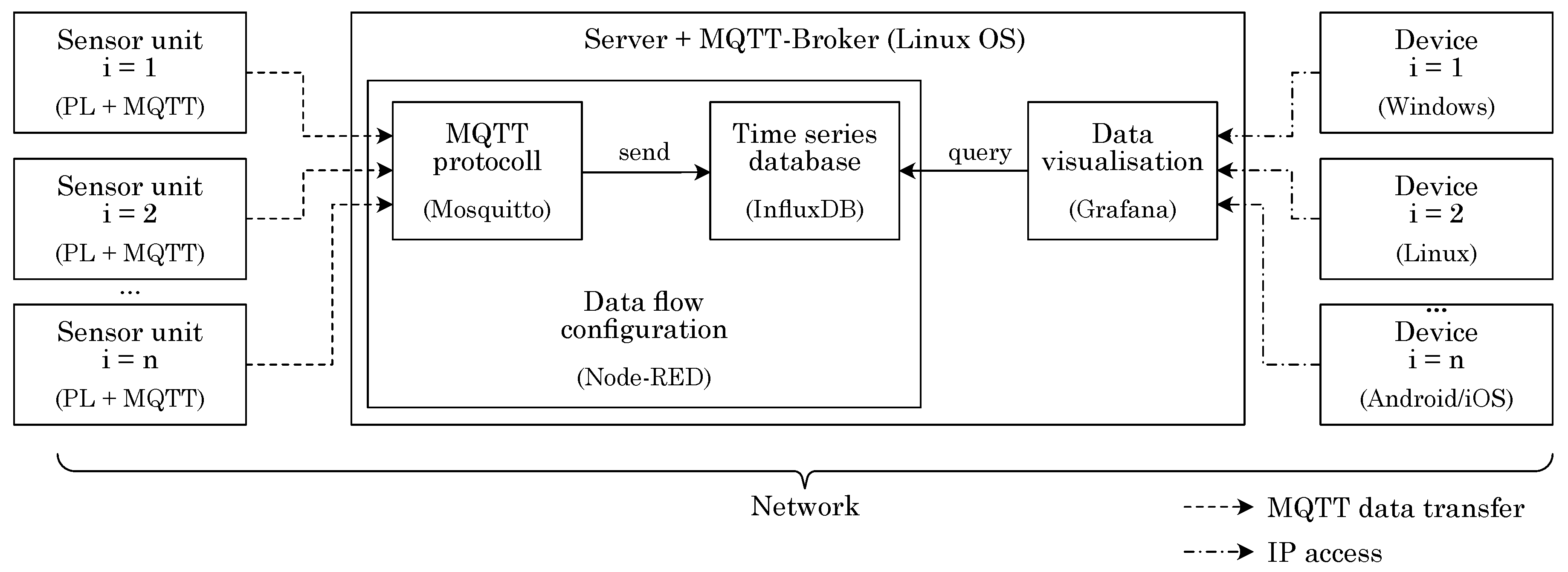

A viable solution for real-time data collection of critical process parameters such as temperature and energy consumption (in this work) essentially consists of four core components, as shown in

Figure 3.

Starting with the selection of a suitable communication protocol that defines the rules and processes according to which the various Industrial-Internet-of-Things (IIoT) devices and systems for process monitoring can communicate with each other. In addition to alterantives such as AMQP [

45,

46,

47] and HTTP/REST [

48], the MQTT communication protocoll is a suitable choice for the use case described here. The MQTT communication protocol was originally developed in 1999 for the satellite-based connection of oil pipelines with the lowest possible energy requirements and bandwidth. While MQTT stood for Message Queuing Telemetry Transport, today it is just the title of the protocol. MQTT has been an officially recognised OASIS standard since 2014. In 2019, the new functions and specifications of version MQTT 5 were ratified, which contain new functions necessary for IoT applications [

49,

50]. The most important advantages include speed, reliability, simplicity, energy efficiency, available support, the possibility of TLS-protected measurement data transmission and the almost unlimited number of connectable devices [

51]. It is used as standard by companies specialising in IoT solutions such as IBM [

52] and AWS [

53].

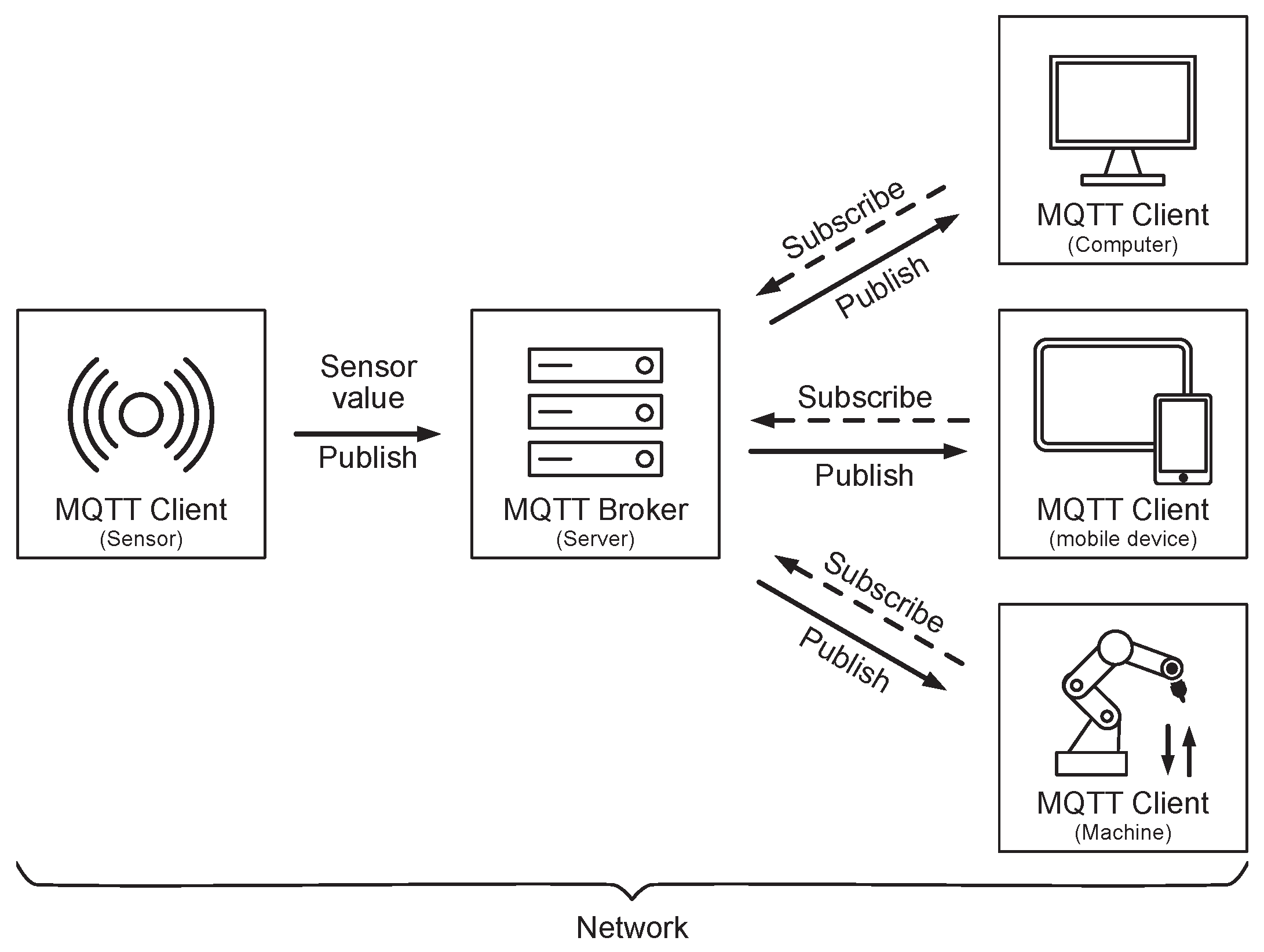

Figure 4 illustrates the basic structure of the MQTT system.

The central element is the so-called MQTT broker, which manages the transfer of information between the MQTT clients that send information (publishers) and the MQTT clients that receive the information (subscribers). There is therefore no direct connection between the clients. However, a client can also be both a publisher and a subscriber, for example a temperature controller that receives the temperature value to be set and sends back the newly set parameter. Information such as sensor values are published via multi-level topics, e.g.

. Clients can register for these topics in order to receive the topic-related sensor values. The MQTT protocol can easily be used in existing internal networks and is very flexible in terms of the number and type of clients, as long as they have an MQTT library available for the most common programming languages. MQTT therefore enables comprehensive and flexible monitoring of the process chain when using the right sensor and server (broker) technology [

50,

54,

55].

Based on that, the selection and use of a programming tool is required to coordinate the input and output and, if necessary, the processing of the sent measurement data. For this purpose, Node-RED is a popular solution with numerous functions and extensions. It was developed by IBM in 2013 with the aim of providing a simple and flexible tool for the Internet of Things (IoT). It allows the visual creation of complex workflows and automations with minimal programming effort and can therefore also be used by people without extensive programming knowledge. Its areas of application are in home automation, industrial automation, data acquisition and IoT systems. Numerous extensions are available for Node-RED, allowing it to cover a very wide range of industrial applications and making it compatible with many state-of-the-art technologies, including Modbus and Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture (OPC-UA) [

56,

57,

58,

59].

Using Node-RED, the data must be transferred and stored to a so-called time series database together with a time stamp that allows the measurement data to be precisely assigned to a specific time. Time series databases, such as InfluxDB, allow even large amounts of data to be stored and read out quickly [

60,

61,

62].

If the aim of data acquisition is to go beyond mere storage and enable the quasi real-time visualisation of this measurement data, a visualisation tool such as Grafana is required. It queries the process data directly from the database, allows for the flexible, need-based visualisation of the measurement data in dashboards and makes the data accessible to specific target groups such as production employees or the management [

63,

64]. All software components, MQTT, Node-RED, InfluxDB and Grafana, are open-source-software (OSS). The whole concept is summed up and illustrated in

Figure 5.

3. Preliminary Considerations

The motivation for the development of a concrete digitalisation concept for a casting plant basically results from the introduction described above. Whether research and development or series production/process: in most cases, the first question that arises is what process data needs to be recorded. Since the quality of all castings (here representative of other, alternative thermally manufactured products) depends to a considerable extent on the temperature regimes at which the castings are manufactured, the temperature is a good place to start, summarised for the following reasons:

Temperature is the dominant parameter in almost all process steps along the process chain required for casting production.

High technological standardisation with regard to the design and interfaces of available thermocouples.

A standardised solution for all stations is therefore conceivable.

Casting quality directly dependent on casting/melt and mould temperature.

Temperature can be controlled directly by the employee, especially in small and medium-sized foundries (assuming it is known).

Generation and maintenance of process temperatures of the largest energy consumers in foundries and thermal industrial processes.

Since the maintainance of (high) temperature levels normally results in high energy consumption as an important cost driver, the exact measurement of the energy demands has high potential for process but financial optimisations as well. The aim should be to be able to specify exactly how much energy was actually consumed for each product and each batch, i.e. to be able to specify a product-specific ‘per capita consumption’. From an ecological point of view, this allows an valid calculation of the process-related CO2 emissions for the whole process as well as for every manufactured product. In principle, the aim must be for all relevant process data to converge in a common database that is able to process this data as quickly as possible and make it available to other programs - such as those for visualisation and analysy (keywords: Big data and data science).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Foundry Equipment

The casting station available for the test setup includes a resistance-heated, tiltable melting furnace from Balzer on an industrial scale with a maximum capacity of 770 kg molten aluminium, which is used for melting, holding and casting. A two-part, preheatable mould with a cavity volume of approx. 0.015 m³ (corresponds to approx. 40 kg aluminium casting weight) is used as a casting mould. The mould is temperature-controlled using a system control with JUMO LC300 temperature controllers. In addition to the furnace, the mould and their respective controllers, other systems relevant for the casting process are used, which will not be discussed further here in order to focus purely on monitoring the temperature curves and energy consumption.

4.2. Measuring Instruments

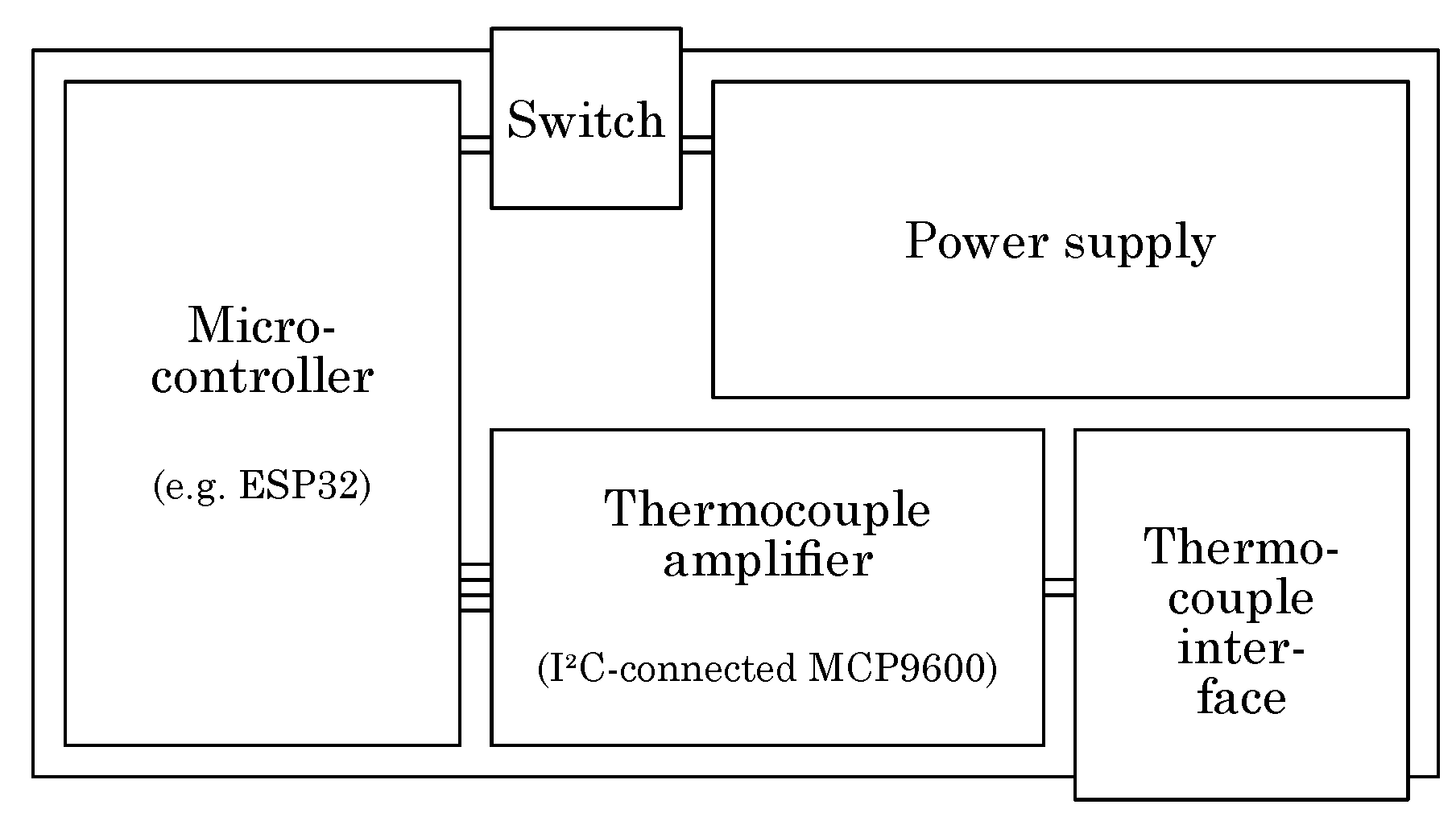

The communication infrastructure for data transmission is provided by a network generated by a Fritzbox 4040. The entire sensor-based process monitoring itself is based on ESP32 microcontrollers (ESP32) on the hardware side. These are equipped with Wi-Fi and represent a cost-efficient and powerful solution for processing and transmitting (measurement) data. Specially developed measuring units based on the ESP32 using a MCP9600 thermocouple amplifier are used for temperature measurement. They allow flexible and demand-orientated application and can be operated both with a rechargeable battery and from the mains. The variants used have a PCC connector (miniature plug connection) for the connection of the thermocouples (TC), but can also be equipped with a direct wire connection or M12 connector. The TC-amplifier chip used in the measuring device allows the use of TC-types J, K, T, N, E, B, S and R. Tests with a thermocouple calibrator (Fluke 714B) have proven reliable measurement up to a temperature of slightly more than 1,600 °C. The temperature measuring device for furnace melt temperature monitoring disposes of one connector, while version for the mould temperature monitoring has seven. For better unterstanding of the principle setup, the schematic setup of the temperature measurement device with one connector can be taken from

Figure 6.

In terms of energy data recording, the ESP32 can be found in 3-phase power consumption meters from Shelly. These are installed in two different versions: The Shelly Pro 3EM - 120A is installed within the moulds temperatur control, while the Shelly Pro 3EM - 400A has been installed within the machine control of the melting furnace. Both Shelly-devices come with WLAN and MQTT support as standard and therefore can be flexibly and easily integrated into the digital infrastructure described above. All measurement data are transmitted to a broker via MQTT according to the concept described above.

4.3. Software/Digital Infrastructure

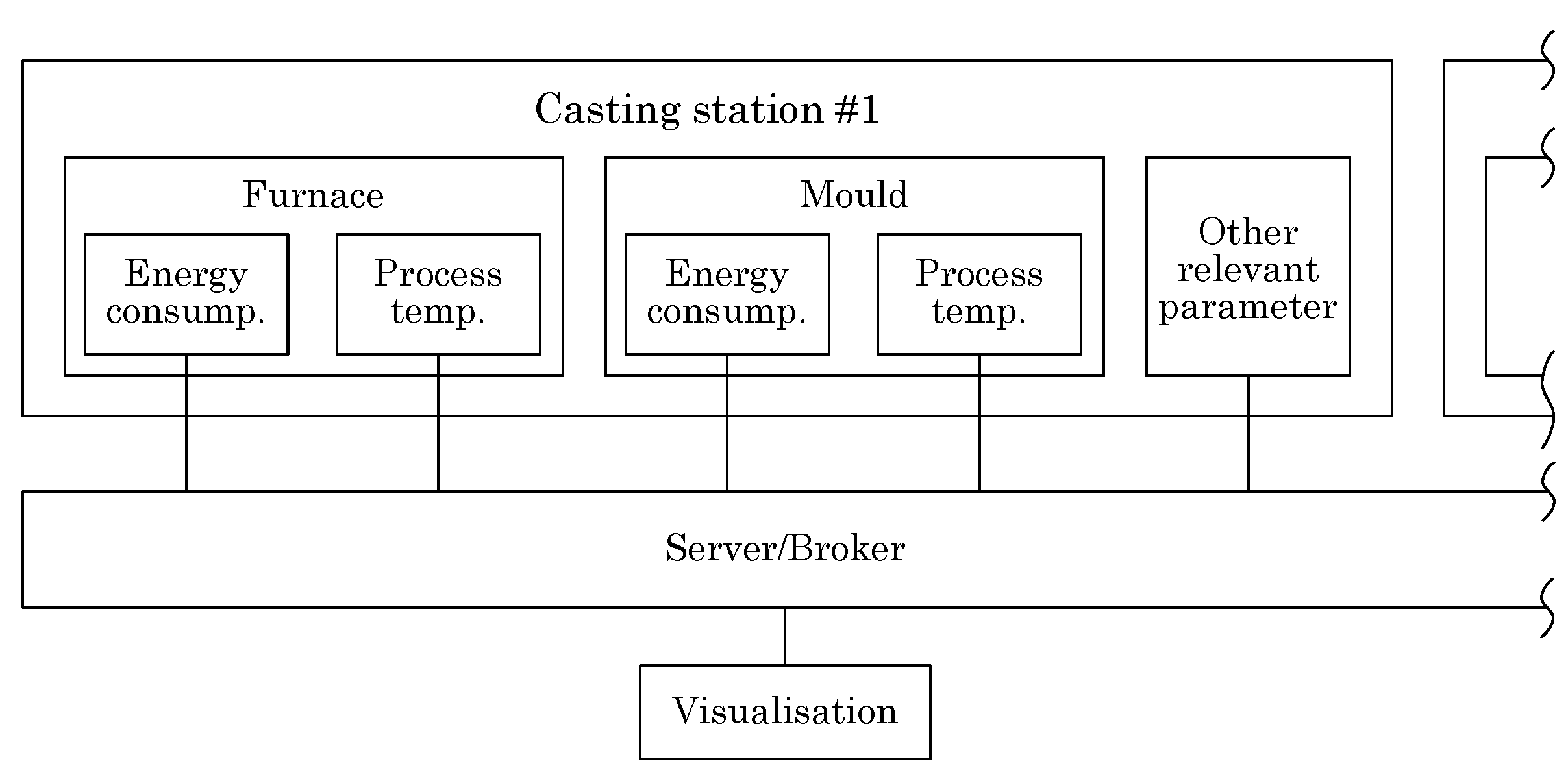

The entire technical implementation is based on the components described in the concept section. The MQTT protocol provides the basis, which is used to exchange process data between clients and brokers within an (internal) WiFi-network. Node-RED enables the definition and regulation of the data flow on the device that serves as a broker. In this specific case, this is the transfer of the data from the temperature und energy consumption sensors sent via MQTT to the broker and within the broker into the InfluxDB database. For real-time visualization of the measurement data, Grafana queries the data to be visualized directly from the Influx database. The MQTT broker, Node-RED and InfluxDB as well as Grafana run on the same system with a Linux operating system (Ubuntu). As shown in

Figure 7, the overall system for process data acquisition described up to this point is scalable and can easily be expanded to include additional casting/process stations.

5. Results

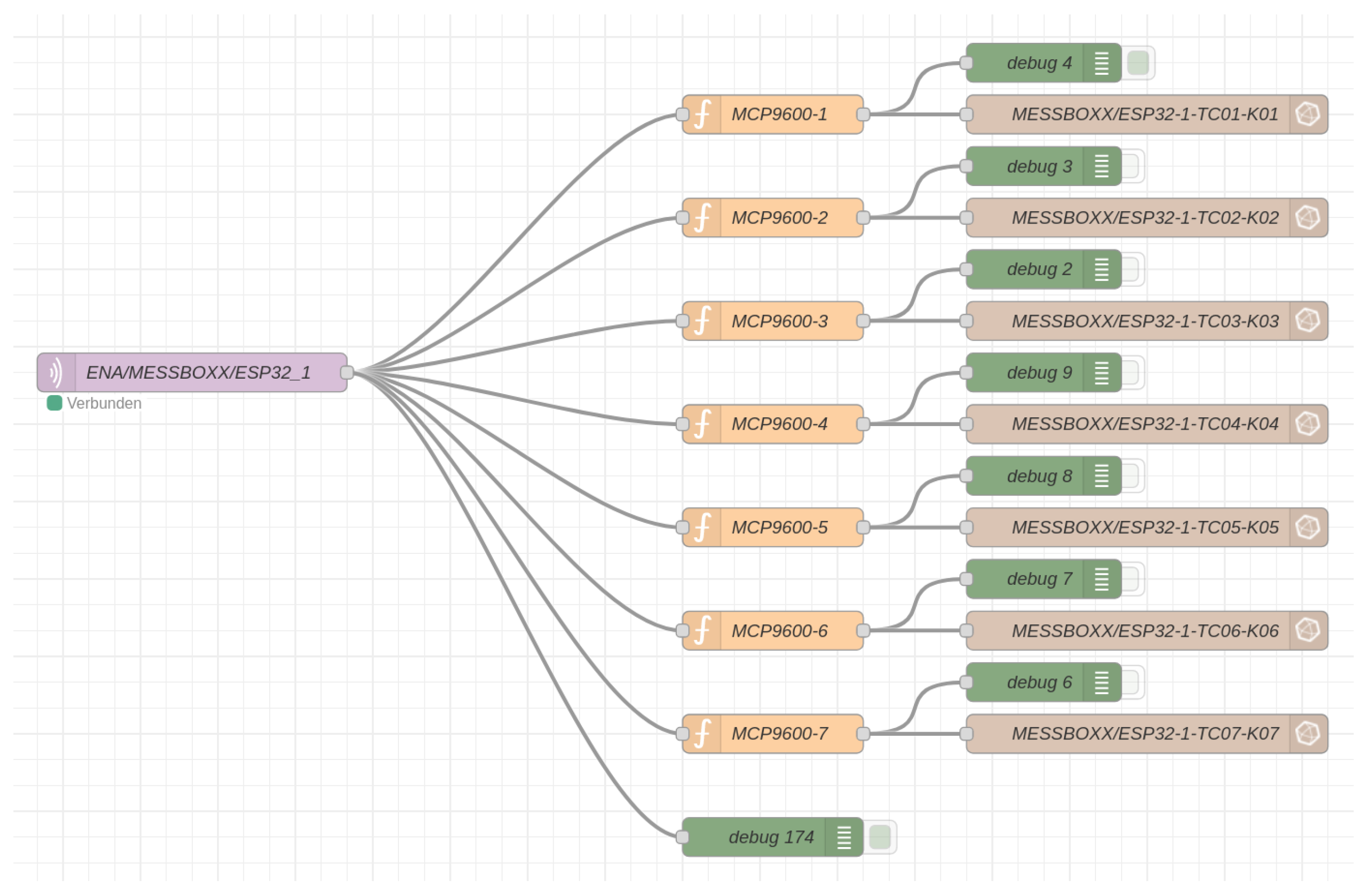

The results are shown here in form of the Node-RED configuration and the final dashboard. The latter is the result of the functional combination of all previous steps. Starting with the Node-RED configuration for transferring the measurement data to the database,

Figure 8 shows a screenshot of it. It illustrates, from left to right, the input of several temperature measurement data (purple nodes), from which the individual measurement data is extracted with the help of function nodes (beige) and transferred to the database (brown nodes). Green nodes, so-called debug nodes, are used to check the data stream.

In case of succesful saving the measured data, the respective data series can be chosen within the Grafana software for visualisation.

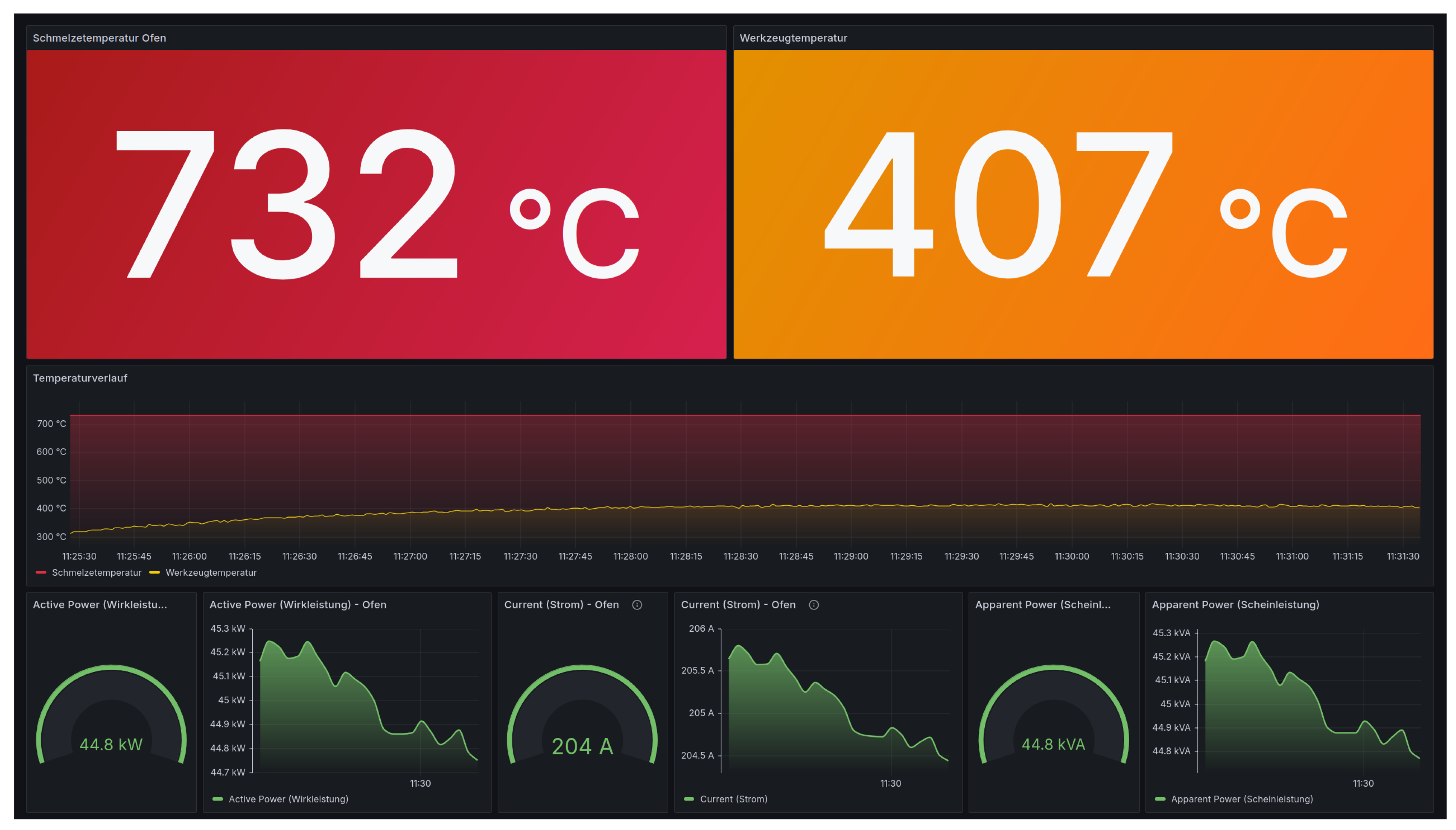

Figure 9 shows an example of a dashboard created with Grafana for process data visualisation for the use case described here. The dashboard shows the current temperature data of the furnace and the casting mould at one measuring point each, as well as their progression over time below. The bottom row shows the current energy consumption data for active power, current and apparent power over time.

Once the data are archives succesfully within the database, the process data can be extruded from the database directly or - in some cases more ergonomic und user-friendly - via Grafanas data exploring tool. The export functions allows for the Excel-friendly saving of the choosen data as csv-files, which can be analysed within excel or they are prepared in an adequate format for automatic data analysis using special data analysis software.

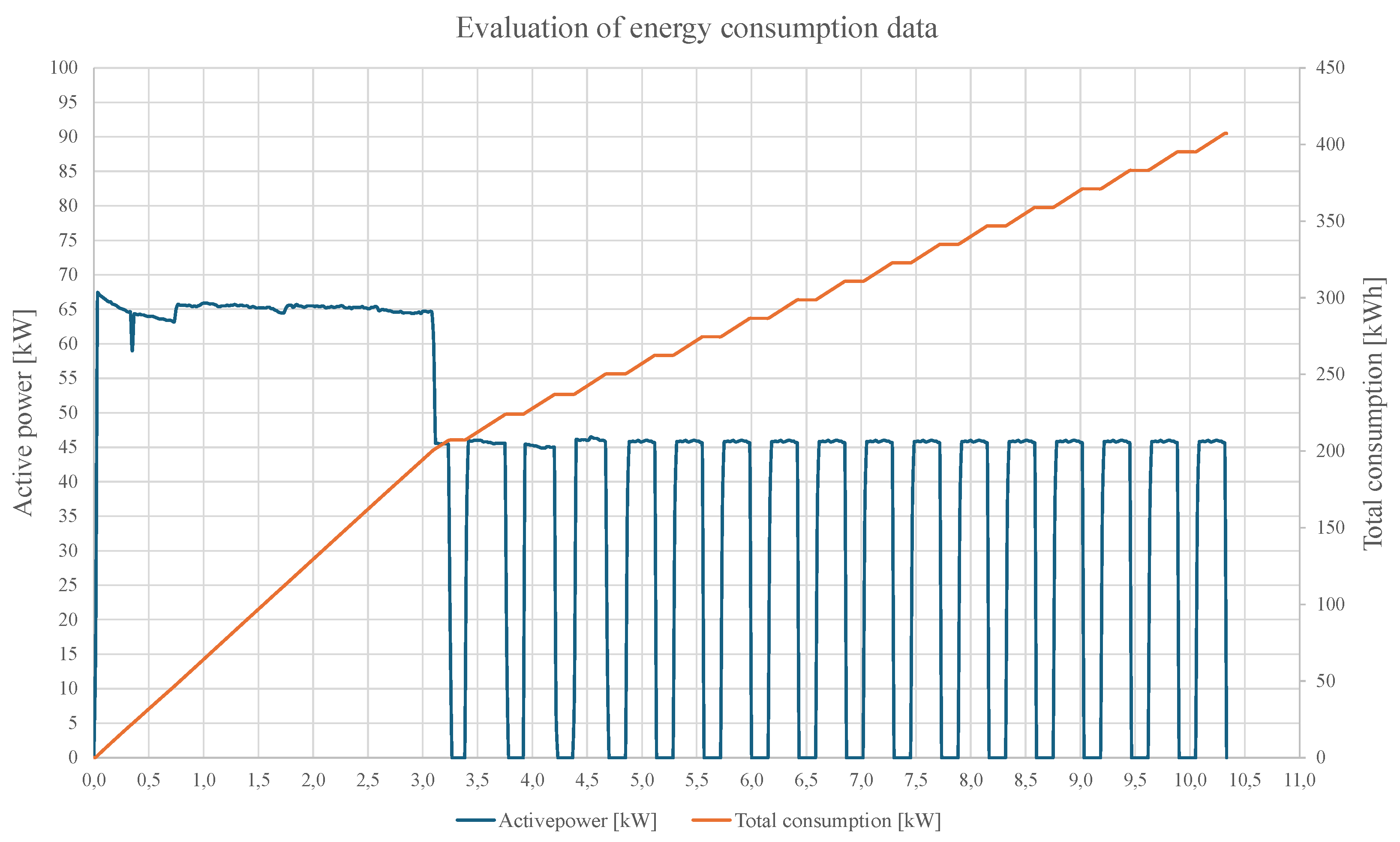

Figure 10 shows the plain analysis of the energy data using the example of an exemplary furnace and tool operation on the basis of the recorded process data. This clearly shows the energy consumption for heating (left), the consumption for control-related oscillation around the set temperature (right) and the cumulative total consumption (orange).

6. Discussion

The solution presented for real-time process recording is not without alternative. It is the solution that helps to effectively implement the project of flexible and targeted process recording. The approach shown has the following advantages and disadvantages.

6.1. Advantages

Thanks to the low cost of the components and the use of OSS, the solution is cost-efficient and flexible, customizable, expandable and scalable. In order to get a sense of whether the solution is suitable for your own operational needs right from the start, all software programs can initially be run on existing computers (age <= 5 yeards), thus reducing the risk of making the wrong decisions. Although this is not a plug-and-play solution, it does offer the opportunity to become familiar with a new area of technology that is becoming increasingly important and to gain a degree of independence in this field. Thanks to the use of widely available software tools, numerous free tutorials and forums can be used for familiarization. In addition, as confirmed by our own experience, the use of AI such as ChatGPT vehemently reduces the software-related development effort [

11] and can quickly clarify questions of understanding. The number of MQTT-capable measuring devices is constantly increasing, as is the number of measured variables that can now be recorded in compliance with Industry 4.0 and integrated into infrastructures such as the one presented here. In addition to the presentation and knowledge of the actual data, the amount of data collected over an appropriate period of time allows a well-founded analysis of the process conditions and the determination of optimisation potentials that might otherwise not be exploited to this extent. This includes, for example, the precise recording of cycle times, the casting/product-related energy ‘per capita consumption’ and the calculation of the associated CO

2 emissions. In addition, it is also possible to indirectly record the condition of thermal systems, which consume more energy as the degree of wear on certain components increases. This increase in energy can be recorded over the life cycle of these wearing parts so that action can be taken in good time in terms of predictive maintenance. Node-RED is not only a software tool that has proved enormously popular, reduces programming effort and unites a large user community, but also, with a view to the future, expands its competencies and functions through the possibility of integrating new function nodes as they become available. Compatibility with various interfaces and communication protocols (e.g. MQTT, AMQP, Modbus) enables the merging of incoming data and thus meets the heterogeneous conditions prevailing in many SMEs with regard to plant technology. For example, it is also compatible with OPC-UA, which expands Node-RED’s functionality for future important protocols and strengthens its own status. This way, comprehensive (abstract) process transparency can be realized, which finally enables the creation of a sound data basis for in-depth process analyses, on the basis of which stages 5 and 6 of the Industry 4.0 development path (

Figure 1) can be worked out. According to the authors, one of the main advantages for companies is the enormous expansion of the quality assurance infrastructure. On the one hand, with regard to the acquisition of new projects, as the comprehensive data recording creates new possibilities for process control and reproducibility. Secondly, because this creates a sound basis for error analyses, which may be necessary at a later date and which would previously have been difficult to carry out due to a lack of documentation.

6.2. Disdvantages

Although forums, tutorials and artificial intelligence drastically reduce the familiarisation time in the technology field of Industry 4.0, the basic familiarisation with such a constantly changing technology field, which also spans all industries, requires a considerable amount of time to develop a rough overview of the solutions that are suitable for your own company. From a business perspective, it is necessary to familiarise an employee with these topics, ideally with an affinity for such topics, who could otherwise be deployed elsewhere. In addition, a solution set up in this way often does not comply with standardised cyber security requirements in some areas. IT security is an important, easily underestimated aspect that requires special attention, the more so, the greater the company’s unique selling points on the process side. The transparency created with the solution presented here relates not only to systems and processes, but also to employees. For example, the cycle times of different employees are visible and can be compared with each other. This requires responsible handling of the data. Results should be used in favour of employees (training, exchange of experience) and not against them (warnings, dismissal, harassment).

The first two disadvantages mentioned can be overcome through targeted training, the use of artificial intelligence such as ChatGPT and, in the case of IT security requirements, in consultation with the relevant certification authorities. Avoiding conflicts when dealing with sensitive employee data requires responsible handling by the management and can above all be seen as an opportunity to improve processes while taking the well-being of employees into account.

6.3. Current Status and Future Work

The current status of process data acquisition at the casting station goes beyond the focus presented here. The need for additional plant technology such as a foundry degassing unit for degassing the aluminium melt and other points also makes their integration into a digital infrastructure necessary. Such systems are often integrated via industrially standardised Modbus interfaces (RTU or TCP/IP), which is possible with the infrastructure presented here and has already been implemented. In addition, manual input of certain measured variables is necessary and possible, especially for manually performed work steps that must also be recorded for comprehensive process recording.

The article outlines a possible solution that allows the field of to enter the field of Industry 4.0 up to and including level 4. Level 5 and level 6 thus represent future development goals. These can also be achieved with the help of the system described, but require the availability of results data. For cast part production, this includes data on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the parts. If this data is available, it is possible to make predictions (stage 5) about the influence of the existing production parameters on the cast part properties. If the target properties are specified accordingly, a self-regulated adaptability (stage 6) of the process parameters can be realised on this basis. This requires a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the production data and the resulting result data, which can only be realised manually with a considerable amount of time. At this point, the targeted use of open-source machine learning tools/artificial intelligence for analysing and forecasting production data will be investigated in the future. Other activities will also focus on further developing the robustness of the sensor units and the IT infrastructure as a whole.

7. Conclusions

This paper describes a concrete, realised solution for SMEs for the real-time recording of thermally demanding processes based on open source software. Temperature data and the associated energy consumption data are at the focus of the process monitoring. This data is available for real-time visualisation and subsequent data evaluation. Both were demonstrated using a specific example. The advantages described in the discussion section are primarily a pronounced process transparency, the possibility of a higher degree of process understanding and an expansion of operational quality assurance and management. The disadvantages include long familiarisation periods (in case an employee has to familiarise themselves with this topic for the first time), the effort required to ensure IT security and the risk of incorrect handling of employee-related data. Nevertheless, all in all, the solution enables the implementation of a comprehensive real-time monitoring system for industrial thermal processes with the potential to make the benefits of Industry 4.0 accessible to SMEs in the relevant sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R.; methodology, E.R.; software, E.R..; validation, E.R.; formal analysis, E.R.; investigation, E.R.; resources, E.R.; data curation, E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.R.; writing—review and editing, E.R.; visualization, E.R.; supervision, E.R.; project administration, E.R.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible and supported by ENA - Elektrotechnologie und Anlagenbau GmbH, Industriestraße 3, 39443 Atzendorf, Germany, in particular by the employee Florian Quack, within the framework of the above-mentioned funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMQP |

Advanced Message Queuing Protocol |

| HTTP(S) |

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (Secure) |

| I4.0 |

Industry 4.0 |

| IEA |

International Energy Agency |

| IIoT |

Industrial Internet of Things |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IP |

Internet Protocol |

| MQTT |

Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| OPC UA |

Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture |

| OS |

Operating system |

| OSS |

Open-source Software |

| REST |

Representational State Transfer |

| RTU |

Remote Terminal Unit |

| SME |

Small and medium sized companies |

| TC |

Thermocouple |

| TCP |

Transmission Control Protocol |

| TCP/IP |

Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol |

| TLS |

Transport Layer Security |

References

- Schuh, G.; Anderl, R.; Dumitresco, R.; Krüger, A.; ten Hompel, M. Industrie 4.0 Maturity Index. acatech STUDY Update 2020. https://en.acatech.de/publication/industrie-4-0-maturity-index-update-2020/.

- Kagermann, H.; Wahlster, W. Ten Years of Industrie 4.0. Sci 2022, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, S.M.; Komarasamy, D.; Mohanapriya, S.; Iyapparaja, M.; Prabavathi, R. Industry 4.0: The Role of Industrial IoT, Big Data, AR/VR, and Blockchain in the Digital Transformation. Smart Computing Techniques in Industrial IoT 2024, pp. 11–39. [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2023. OECD Publishing 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, E. Industrie 4.0 - The role of IIoT in digital transformation of the manufacturing. Comarch Technologies - White Paper 2022.

- Bischoff, J. Erschließen der Potenziale der Anwendung von ,Industrie 4.0‘ im Mittelstand (engl. Unlocking the potential of the application of ,Industry 4.0’ in SMEs). agiplan GmbH 2015.

- Meyer, L.; Reker J. Industrie 4.0 im Mittelstand (engl. Industry 4.0 in the SME sector). Deloitte 2016.

- Schröder, C. Herausforderungen von Industrie 4.0 für den Mittelstand (engl. Challenges of Industry 4.0 for SMEs). Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung 2016.

- von Wascinski, L.; Weiß, M.; Tilebein, M. Industrie 4.0 für die Textil und Bekleidungsindustrie (engl. Industry 4.0 for the textile and clothing industry). KMU 4.0 - Digitale Transformation in kleinen und mittelständischen Unternehmen 2018.

- Kinkel, S.; Beiner, S.; Schäfer, A.; Heimberger, H.; Jäger, A. Wertschöpfungspotenziale 4.0 (engl. value creation potential). Institute for Production Maintenance 2021.

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Pratap Singh, R. A study on ChatGPT for Industry 4.0: Background, potentials, challenges, and eventualities. JET 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Federal Statistical Office. Small and medium-sized enterprises. GFSO 2024. https://www.destatis.de.

- Platform Industrie 4.0. White Paper on Manufacturing-X. BMWK 2022. https://www.plattform-i40.de.

- Häring, K.; Pimentel, C.; Teixeira, L. Industry 4.0 Implementation in Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Recommendations Extracted from a Systematic Literature Review with a Focus on Maturity Models. Logistics 2023, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inernational Energy Agency. Renewables 2019 - Analysis and forecast to 2024. IEA 2019. https://www.iea.org/energy-system/industry.

- Matsunaga, N.; Kawaji, S.; Tanaka, M.; Nanno, I. A novel approach of thermal process control for uniform temperature. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 2005, 38, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulău, M. Control Strategies for Thermal Processes in Chemical Industry. Proceedings 2020, 63, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zeng, Jq. Consideration of green intelligent steel processes and narrow window stability control technology on steel quality. Int J Miner Metall Mater 2021, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zier, M.; Stenzel, P.; Kotzur, L.; Stolten, D. A review of decarbonization options for the glass industry. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otitoju, T.A.; Okoye, P.U.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Okoye, M.O.; Li, S. dvanced ceramic components: Materials, fabrication, and applications. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2020, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Sparks, L. Temperature Controlled Supply Chains. Food Supply Chain Management 2003, pp. 179–198. [CrossRef]

- Raab, V.; Petersen, B.; Kreyenschmidt, J. Temperature monitoring in meat supply chains. British Food Journal 2011, 113, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, E.; Woschank, M. Industry 4.0 for SMEs - Smart Manufacturing and Logistics for SMEs. MDPI Books 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dossou, P.-E.; Laouénan, G.; Didier, J.-Y. Development of a Sustainable Industry 4.0 Approach for Increasing the Performance of SMEs. Processes 2022, 10, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.Y.; Ong, C.H. Industry 4.0 Competencies and Sustainable Manufacturing Performance in the Context of Manufacturing SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. Sage Open 2024, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bührig-Polaczek, A.; Michaeli, W.; Spur, G. Handbuch Urformen (engl. Handbook primary forming). Carl Hanser GmbH + Co.

- Herfurth, K.; Scharf, S. Casting. In: Grote, KH., Hefazi, H. (eds) Springer Handbook of Mechanical Engineering. Springer Handbooks 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittur, J.K.; Patel, G.C.M.; Parappagoudar,M.B. Modeling of Pressure Die Casting Process: An Artificial Intelligence Approach. International Journal of Metalcasting 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ravi, B. SMART Foundry 2020. IEEE Potentials 2016, 35, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, J.; Silka, R.; Górski, F.; Ciszak, O. Modeling of Foundry Processes in the Era of Industry 4.0. IEEE Advances in Design, Simulation and Manufacturing 2018. [CrossRef]

- Vanli, S.; Akdogan, A.; Kerber, K.; Özbek, S.; Durakbasa, M.N. Smart Die Casting Foundry According To Industrial Revolution 4.0. Acta Technica Napocensis 2018, 1, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Liszka, K.; Klimkiewicz, K.; Malinowski, P. Polish Foundry Engineer with Regard to Changes Carried by the Industry 4.0. Archives of Foundry Engineering 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzyk, M.; Dybowski, B.; Kozlowski, J. Introducing Advanced Data Analytics in Perspective of Industry 4.0 in a Die Casting Foundry. Archives of Foundry Engineering 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.K.; Banerjee, P.; Baksi, D.; Samanta, S.K. IoT Based Interface Device for Automatic Molding Machine towards SMART FOUNDRY-2020. ICCCNT 2019. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Papanikolaou, M.; Pagone, E.; Salonitis, K.; Jolly, M.R. Digital Manufacturing for Foundries 4.0. Light Metals 2020 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipov, M.V.; Matrosova, V.V.; Volnov, I.N. Automation in Foundry Industry: Modern Information and Cyber-Physical Systems. Advances in Automation 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacecic, L.; Oliveira, R.; Terek, P.; Terek, V.; Pristavec, J.; Skoric, B. The Direction of Foundry Industry: Towardthe Foundry 4.0. JMAIT 2020, 5, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Miskinis, G.V. Transformation of the Modern Foundry. International Journal of Metalcasting 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, S.; Sander, B.; Kujath, M.; Richter, H.; Riedel, E.; Stein, H.; tom Felde, J. FOUNDRY 4.0: An innovative technology for sustainable and flexible process design in foundries. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, R.; Bruton, K.; O’Sullivan, D.; Keogh, D. Industry 4.0 driven statistical analysis of investment casting process demonstrates the value of digitalisation. Procedia Computer Science 2022, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, P.M.; Kumar, A.P.; Mirji, K.K.; Gokhale, P.; Pote, S.A.; Tigadi, B.S. A Realistic Framework to Assess the Barriers to SCM 4.0 in the Foundry Industry. Journal of Operations and Strategic Planning 2023, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, J.; Singh, P.P. Chapter 2 - Sustainability in foundry and metal casting industry. Sustainable Manufacturing Processes 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyan, T.Ç.; Otto, K.; Silva, M.S.; Vilaça, P.; Armakan, E. Industry 4.0 Foundry Data Management and Supervised Machine Learning in Low-Pressure Die Casting Quality Improvement. International Journal of Metalcasting 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, E.; Ahmed, M.; Hellmann, B.; Horn, I. Foundry 4.0: digitally recordable casting ladle for the application of Industry 4.0-ready manual casting processes. Procedia CIRP 2023, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RabbitMQ. AMQP - Advanced Message Queuing Protocol Protocol Specification - A General Purpose Middleware Standard. amq-spec 2006. https://www.rabbitmq.com/resources/specs/amqp0-9.pdff.

- Adlink. Messaging Technologies for the Industrial Internet and the Internet of Things Whitepaper - A Comparison Between DDS, AMQP, MQTT, JMS, REST, CoAP, and XMPP. Object Management Group 2017. https://www.omg.org/news/whitepapers/Messaging-Whitepaper%20v2.1.pdf.

- Naik, N. Choice of effective messaging protocols for IoT systems: MQTT, CoAP, AMQP and HTTP. IEEE International Systems Engineering Symposium (ISSE) 2007, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Phung, C.V.; Dizdarevic, J.; Jukan, A. An Experimental Study of Network Coded REST HTTP in Dynamic IoT Systems. ICC 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC) 2020, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.; Briggs, E.; Borgendale, K.; Gupta, R. MQTT Version 5.0. OASIS Standard 2019. https://docs.oasis-open.org/mqtt/mqtt/v5.0/mqtt-v5.0.html.

- HiveMQ. MQTT & MQTT 5 Essentials - A comprehensive overview of MQTT facts and features for beginners and experts alike. HiveMQ GmbH 2020. https://www.hivemq.com/blog/announcing-mqtt-ebook/.

- Solovev, A.; Petrova, A. Reasons and peculiarities of choosing MQTT protocol for your IoT devices. Integra Sources 2024. https://www.integrasources.com/blog/mqtt-protocol-iot-devices/.

- Marolleau, B.; Bacle, C.; Laleve, C. IoT application in IBM Cloud with Node-RED and IBM Watson - Version 2.4. IBM Corp 2020.

- AWS Whitepaper. Designing MQTT Topics for AWS IoT Core. Amazon Web Services 2024.

- Desbiens, F. MQTT. Building Enterprise IoT Solutions with Eclipse IoT Technologies 2022, pp. 67–101. [CrossRef]

- Cameron , C. MQTT. ESP32 Formats and Communication 2023, pp. 351–384. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Khanna, V. Implementation and Comparison of MQTT, WebSocket, and HTTP Protocols for Smart Room IoT Application in Node-RED. IoT for Sustainable Smart Cities and Society 20232, pp. 165–193. [CrossRef]

- Kanagachidambaresan, G.R.; Bharathi, N. Introduction to Node-RED and Industrial Dashboard Design. Sensors and Protocols for Industry 4.0. Maker Innovations Series 2023, pp. 225–253. [CrossRef]

- OPC Foundation. OPC Unified Architecture: Interoperability for Industrie 4.0 and the Internet of Things. Version V16 2024. [CrossRef]

- Node-RED. A Node-RED node to communicate via OPC UA based on node-opcua library.. Version: 0.2.337 2024. https://flows.nodered.org/node/node-red-contrib-opcua.

- Naqvi, S.N.Z.; Yfantidou, S; Zimanyi, E. Time Series Databases and InfluxDB. Universite Libre de Bruxelles 2017.

- Giacobbe, M.; Chaouch, C; Scarpa, M.; Puliafito, A. An Implementation of InfluxDB for Monitoring and Analytics in Distributed IoT Environments. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Sciences of Electronics, Technologies of Information and Telecommunications (SETIT’18), Vol.1 2019, pp. 155–162. [CrossRef]

- Deepika, K.; Prasad, B.R. IoT-Based Dashboards for Monitoring Connected Farms Using Free Software and Open Protocols. Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics 2022, pp. 529–543. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Kundan, A.P. Grafana. Monitoring Cloud-Native Applications 2021, pp. 187–240. [CrossRef]

- McCollam, R.; Kundan, A.P. Real-Time Dashboards for IT and Business Operations. Getting Started with Grafana 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).