1. Introduction

Sustainable development is often referred to as a ‘wicked problem’ (Thollander et al. 2019, Pryshlakivsky and Searcy 2013, Frantzeskaki and De Haan H 2009). By definition, wicked problems resist resolution owing to their complexity, dynamic environments, and incomplete or changing requirements (Churchman 1967, Thollander et al. 2019). In the pursuit of sustainability goals, non-standard, innovative and transdisciplinary research approaches have shown promise. Research in living labs is gaining scientific as well as political attention in particular (Bakıcı et al. 2013, Ballon and Schuurman 2015, Bergvall-Kåreborn et al. 2015, Canzler et al. 2017, Schikowitz et al. 2023). Living labs play a central role in delivering the European Commission’s Zero Pollution Action Plan in the years ahead (European Commission 2022). The European Commission strategically supports living labs to strengthen sustainability innovation in the European Union. Furthermore, the European Network of Living Labs (European Commission 2022) was established in order to connect European living labs to facilitate knowledge exchange (Dekker et al. 2020).

Although numerous definitions of living labs exist (Mbatha and Musango 2022, Sovacool et al. 2020, Leminen et al. 2012, Dekker et al. 2020), there are a number of standard characteristic features. Living labs are usually created in real-life environments, focusing on everyday practice and researchKlicken oder tippen Sie hier, um Text einzugeben.. They integrate a broad range of stakeholders such as cities, local communities, enterprises, public administration, political actors and the scientific community (Hossain et al. 2019, Almirall and Wareham 2010). Living labs entail a striving for openness and newness (Schultze and Boland 2000, Bergvall-Kåreborn et al. 2015) such as developing and establishing new practices and artefacts. Arguably the most significant characteristic principle of living labs can be seen in the way in which interventions, results, and new knowledge and practices are created. Living labs facilitate the transdisciplinary co-creation of sustainability interventions through continuous learning and development processes (Hossain et al. 2019). A significant normative component of living labs is the collaborative production of results which aims to empower all participating actors and stakeholders (Nesti 2017). Living labs create spaces for collaborative experimentation and render sustainability experiments a core meta-method (Groß 2005).

The realisation of living labs often presents itself as a novelty and a challenge for academic and non-academic actors in everyday research life. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on challenges in transdisciplinary research often equated with barriers (Bulten et al. 2021, Brouwer et al. 2019), tensions, dilemmas or paradoxes (Lang et al. 2013, Arnold 2022). Hossain et al. (2015) stress the challenges related to the methods and concepts of living labs explored in past studies. Despite the fact that these challenges are diverse and dependent upon the specific contexts in which a living lab is situated, they identify several universal challenges. These include governance, unforeseen outcomes, efficiency, the recruitment of collaborators and the sustainability and scalability of their innovations (Hossain et al. 2015:, p. 983). Tensions and conflicts play a notable role in the analytical examination of challenges in living labs (Leminen et al. 2015b, Schikowitz et al. 2023). Hakkarainen and Hyysalo (2013) point to the general potential for conflict resulting from the heterogenous competencies or contradictory interests of participating actors. In the same vein, Engels and Rogge (2018) address tensions arising from the unilateral compulsion to achieve rapid innovation and economic exploitation within living labs. Furthermore, they set out the challenge of integrating new participants into the living lab. On occasion, this can undermine existing actor dynamics and threaten the established order, thus manifesting a negative consequence of the openness principle.

The emergence of living labs demands a better understanding of the factors that challenge collaboration and of how to deal with them in day-to-day activities (Engels and Rogge 2018, Leminen et al. 2015) Similarly, Ballon (2015) and Westerlund and Leminen (2014) call for a better understanding of the concept and the context of living labs and of the methodologies for co-creating innovation. Recent publications frequently call for further research into living lab processes and methods (Bergvall-Kåreborn 2015, Romero Herrera 2017, Baran and Berkowicz 2020).

Responding to these calls, our study aims to: (1) identify and describe the main challenges of collaboration in living labs and (2) highlight coping strategies for academic and non-academic actors. The findings are drawn upon the experience of three years of transdisciplinary activities in one living lab in southern Germany. Targeting the transition to climate neutrality within the scope of a city group (Konzern Stadt), the living lab integrates areas such as urban mobility, daily routines and day-to-day practices, energy and heating supply, energy communities, buildings and infrastructure. This empirical case study is characterised in particular by a vast diversity of collaborators and stakeholders, as well as complex governance structures.

Our research questions are as follows:

- (i)

What are the key challenges that academic and non-academic actors have to consider in day-to-day living lab research?

- (ii)

What constitutes and shapes the key challenges in collaboration?

- (iii)

What coping strategies can be applied?

We attempt two contributions to the body of knowledge on living lab research by (1) exploring and describing the key challenges to consider in creating and maintaining successful collaboration in living labs and (2) synthesizing these findings to propose various coping modes.

The remainder of this study is organised as follows: The next section provides an overview of the key principles of research in living labs that shape the basic framework for cooperation.

Section 3 describes the methodology, data and methods used. In

Section 4, the key challenges identified are described and discussed in relation to previous studies.

Section 5 discusses the results with reference to three different coping modes. Finally,

Section 6 sets out our final conclusions and points to any limitations as well as to future avenues for research.

2. Key Principles of Research in Living Labs

Research in living labs is conceptually different from traditional research in both the natural sciences and the social sciences (Blackstock et al. 2007, Lang et al. 2012, Huning et al. 2021); a set of specific normative principles has to be applied. In the following, we elaborate on those key principles owing to the fact that: First, they set the framework within which a living lab should be created, organised and governed. Second, the collaborators (academic as well as non-academic actors) are required to commit themselves to those principles in everyday research. Third, those principles are interpreted, discussed and translated in relation to day-to-day practice.

2.1. Transdisciplinarity, Participation and Co-Creation in Living Labs

Transdisciplinarity represents the overarching characteristic feature of living labs research (Baran and Berkowicz 2020, Barth et al. 2023, Feurstein et al. 2008, Dekker et al. 2020, Hossain et al. 2019, Nesti 2017, Puerari et al. 2018). According to Barth, transdisciplinarity in living lab research acknowledges context dependencies related to real-world problems and ‘differentiates and integrates knowledge from different domains, inside and outside academia’ (Barth et al. 2023, p. 2). The idea of co-creation is inherent in the concept of transdisciplinary living lab research. Hence, living labs require an intensive collaboration between academic and non-academic actors to develop tailor-made solutions to a specific problem (Hossain et al. 2019, Dekker et al. 2020, Feurstein et al. 2008, Menny et al., 2018, Huang & Thomas 2021, Hilger et al. 2021). Targeted and co-created solutions promise a better fit between problem and solution by involving the actors who are confronted with the problem in their everyday practices in the solution-finding process (Nesti 2017, Puerari et al. 2018). According to Nesti (2017, p. 268), ‘full co-production entails users and professionals totally sharing the task of planning, designing and delivering the service’. The application of interventions promises less implementation effects when interventions are introduced in the collaborators’ own context and evaluative claims are likely to be well-grounded (Dekker et al. 2020, Brankaert et al. 2015, Shadish et al. 2002, Thøgersen 2005).

2.2. Variety of Collaborators And Real-Life Setting

Living labs bring together collaborators to co-create sustainability solutions, products and innovations in the physical setting in which they are envisioned and ought to be implemented (Dekker et al. 2020: p. 1211). The inclusion of multiple collaborators in the research process is constitutive for living labs. Collaborators can thus be actors from universities or other research institutions, private or state-owned companies, governmental or non-governmental organisations, urban or rural citizens, and agencies, among others (Dekker et al. 2020, Feurstein et al. 2008, Puerari et al. 2018, Westerlund and Leminen 2011, Mbatha and Musango 2022). However, with regard to studies on challenges, the range of collaborators is most frequently narrowed down to the distinction between scientific and non-scientific actors (Barth et al. 2023, Felt et al. 2013), highlighting the threshold with respect to real-life settings.

2.3. Experimentation as a Meta-Method of Sustainability Interventions

In many sciences, experiments are the key method used to gain knowledge and to explore, validate or refute hypotheses. Epistemologically, the experiment constitutes an inductive approach to drawing general conclusions from individual cases. Classical experiments in laboratories can be characterised by the need to control contextual conditions. Similar, but different, experiments constitute the meta-method of creating knowledge in living labs. In contrast to classical experiments, living lab experiments (other commonly used terms: ‘real-life experiments’, ‘transition experiments’, ‘transformational experiments’ or ‘sustainability experiments’) are embedded in social, ecological and technical processes, and conducted and supported by multiple contributors (Castán Broto and Bulkeley 2013, Caniglia et al. 2017, Sengers et al. 2019, Luederitz et al. 2017). Furthermore, interventions are co-created and tested in a real-world and real-time environment (Sovacool et al. 2020), thus limiting the overall controllability and increasing the potential for unintended consequences (Caniglia et al. 2017).

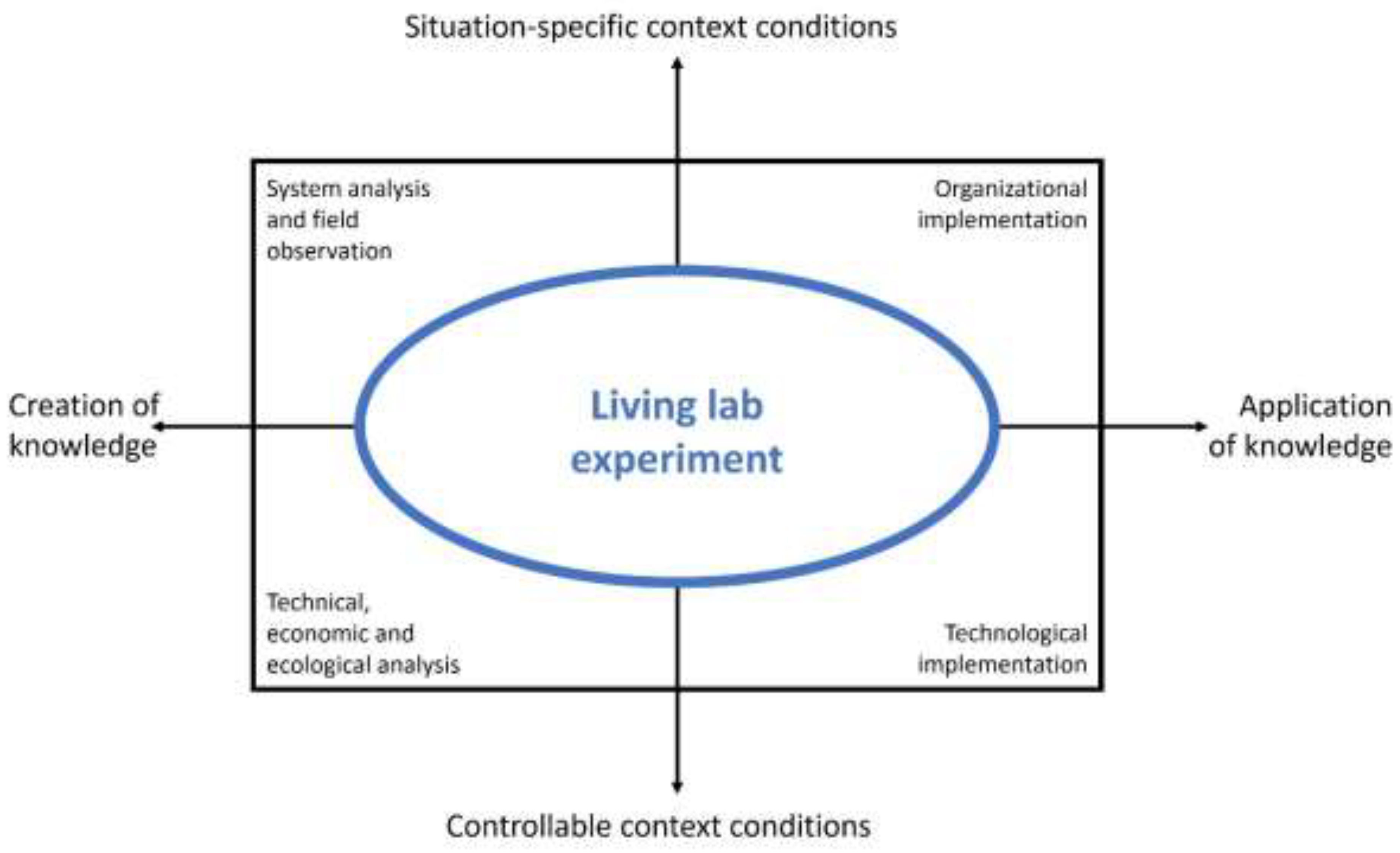

Taking a sociological perspective, Groß et al. (2015) typify the characteristics of living lab experiments in two ways: first, the distinction between application and generation and second, the distinction between situational and controllable context conditions within the field of experiments in sciences. As illustrated in

Figure 1, living lab research combines the creation of knowledge and the application of knowledge (Groß 2005). Hence, living lab experiments shift the emphasis from the mere generation of knowledge to actual actions for sustainability and their institutionalisation. This has two potential implications for collaboration in the living lab. First, the collaborators and stakeholders in the living lab constitute the experimenters who are themselves part of the experiments as well as part of the intervention (Bulkeley 2016). Second, due to their embeddedness in the real-world environment, living lab collaborators have to deal with situation-specific context conditions, such as specific exogenous events or influences, case-specific organisational histories, structures and cultures. Identifying these situation-specific context conditions becomes vital to being able to draw general conclusions for other contexts. Furthermore, and in contrast to classic experiments, experiments in living labs can take spontaneous turns and yield unexpected results (Følstad 2008, Dekker et al. 2020).

2.4. Multiple Methods Approach – Spaces Of Collaboration

The application of multiple methods is a basic requirement of experiments in living labs (Ballon and Schuurman 2015, Dekker et al. 2020). These methods focus heavily on the involvement of academic and non-academic collaborators. After reviewing forty-two empirical articles on living labs, Huang and Thomas (2021) provide a comprehensive overview as well as a thematical categorisation of the vast variety of methods used in living labs (

Table 1). These methods represent the primary ‘spaces of participation’ (Schikowitz et al. 2023). At the same time, the challenges of collaboration manifest themselves in these interactive settings.

3. Materials and Methods

Data generation and analysis follows an explorative qualitative approach and a single case study design (Yin 2014). Our study uses data generated in a living lab research project that targets the transition to climate neutrality within the scope of a city corporation. The living lab is situated in a city in southern Germany with a population of around 120,000 citizens. The transition to climate neutrality is a particularly complex mission in urban contexts.

In order to gain more flexibility and scope for action, municipalities are partially outsourcing their responsibilities to subsidiaries, whose management and organisational form is described under the term ‘city group’ or ‘city corporation’ (Konzern Stadt). City corporations have to tackle a broad spectrum of climate protection-critical tasks of general interest such as wastewater/waste disposal, water/energy supply and public transportation.

Hence, our empirical case study is characterised by a vast diversity of collaborators and complex governance structures. On the one hand, the city corporation which comprises the municipal administration, the city-owned and -operated enterprises and the municipal businesses in which the city has a major interest. Collaborators from these organisations represent what are known as the non-academic actors of the living lab project. On the other hand, the living lab includes personnel from different scientific disciplines (e.g. social science, economics and engineering) from two research institutes, an additional partner supporting moderation processes and an external partner providing coaching and supervision.

At the start of the project and over the course of several workshops, the collaborating actors defined the fields on which the research should focus, namely municipal mobility, energy and heating supply, energy communities, buildings and infrastructure, daily routines and day-to-day practices. The living lab experiments were carried out in these areas from 2021 to 2024. Hence, our data collection and analysis derive from a three-year period.

Paradigmatically and epistemologically, we adopted a social constructivist worldview (Creswell 2009). This perspective adheres to the sociological premise that meanings (e.g. of collaboration within a living lab) develop mutually in social and cognitive interpretation processes, and those practices and interventions result from these meanings (Blumer 1986).

The main purpose of our data generation strategy was to (re)construct the development of challenges in collaboration (e.g. tensions and conflicts) by identifying themes and patterns. The data generation was mainly based on qualitative interviews with collaborators (academic and non-academic actors) engaged in the living lab. In total, twenty in-depth interviews (one-on-one and in a group) were carried out with an average duration of around two hours each. Interviews were conducted with research personnel (senior and junior project leaders) as well as with employees of the various organisational units within the city corporation (e.g. city administration, city utility, public transportation, wastewater) which are particularly involved in everyday collaborative work. In addition, observations drawn from participation in workshops, project meetings and formal and informal discussions were included in the process of data generation.

The interview data was collected by means of semi-structured narrative interviews (Froschauer and Lueger 2020). This method focuses on the interviewees’ narrative perspective and topics. The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. The generated texts (primarily interview text and observation protocols) were analysed by means of thematic analysis (Froschauer and Lueger 2020). Thematic analysis is particularly suitable for a large number of interview texts and serves two purposes. First, to provide an overview of the content of the interviews, to summarise their core statements and to analyse the context of their use. Second, the diverse themes addressed can be analysed as a whole, systematised and condensed (Frank et al. 2016).

4. Results

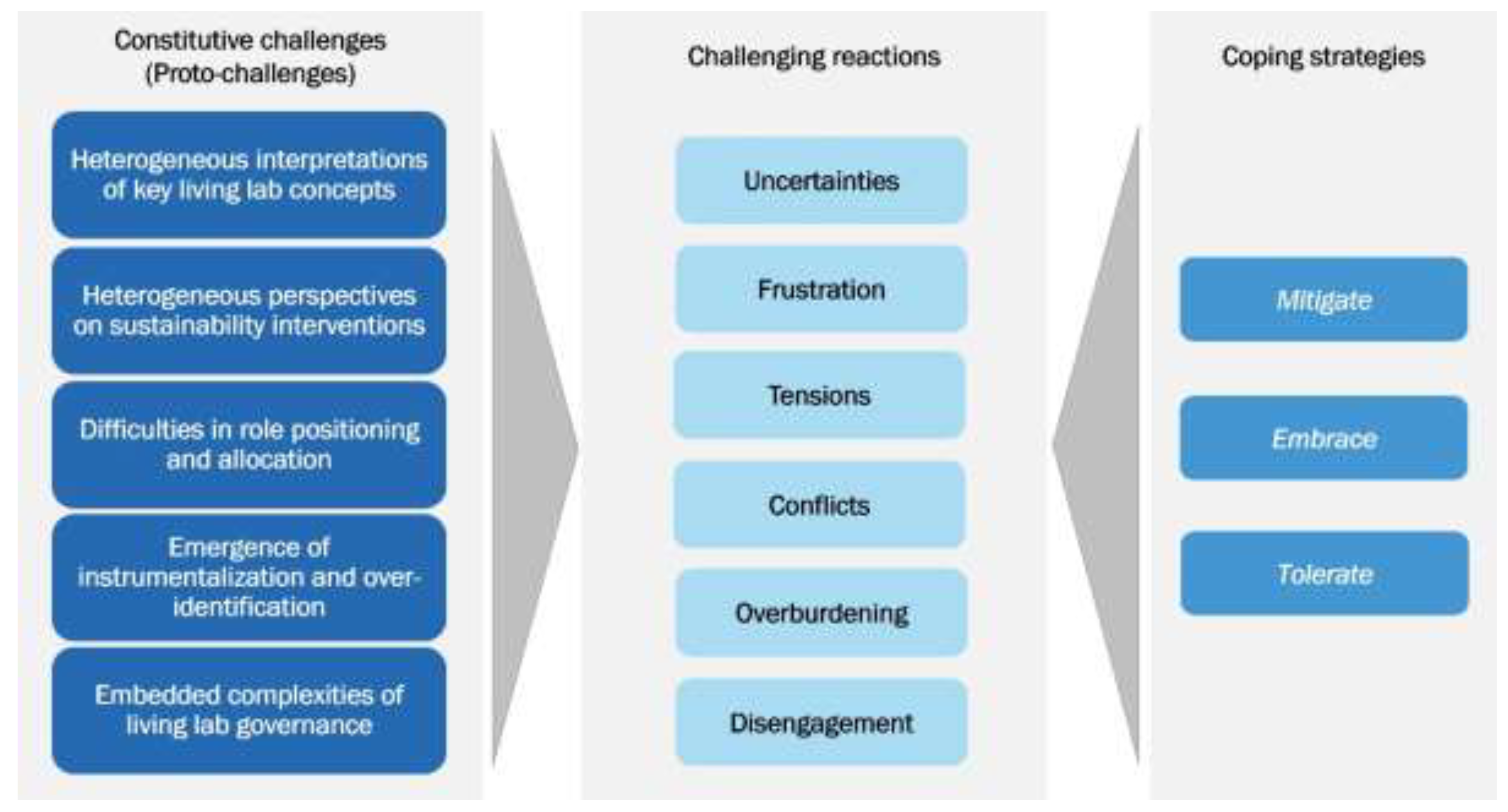

As mentioned in the introduction, a number of studies (Hossain et al. 2015, Brouwer et al. 2019, Bulten et al. 2021) have identified challenges in collaborative research. A conceptual or uniform definition of the term is not always provided. For example, conflicts (Hakkarainen and Hyysalo 2013, Leminen et al. 2015b, Schikowitz et al. 2023) undoubtedly represent challenges of collaboration in everyday research. However, our data analysis showed that such situations should rather be treated as contingent outcomes of underlying distinct processes (i.e. proto-challenges). As a result, reactions to negatively perceived collaboration, which were sometimes explicitly and implicitly described as challenges in the interviews, were coded as challenging reactions, namely: uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts and disengagement.

These challenging reactions often mark turning points in collaboration, potentially threatening or irritating the progress of a living lab research project. Our analysis shows that these reactions are shaped by (1) heterogeneous interpretations of key living lab concepts, (2) heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, (3) difficulties in role positioning and allocation, (4) emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and (5) embedded complexities of living lab governance (Fig. 2). In the following, these interrelated proto-challenges are described and discussed in the broader research context.

Figure 2.

Overview – Challenging reactions and proto-challenges of living lab collaboration.

Figure 2.

Overview – Challenging reactions and proto-challenges of living lab collaboration.

4.1. Heterogeneous Interpretations of Living Lab Key Concepts

Designing and establishing a living lab project requires the translation of the key concepts into practice. For this reason, the key concepts were introduced and discussed in a series of workshops during the design phase of the project in order to achieve a joint understanding among all collaborating actors. Since then, living lab experimentation, participation and co-creation have established themselves as shared pillars of collaboration as well as points of reference in day-to-day research. The analysis of the interviews and observation protocols showed a strong consensus on targeting these key principles, but no uniform interpretations from the collaborators. On the contrary, we identified distinct differences in the interpretations of these concepts, mostly embedded in narratives and reports about challenges such as uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts and disengagement. In an earlier study, Felt et al. (2012) point to the diverse imaginations of participation by academic actors in transdisciplinary research. In their study of four European living labs, Huning et al. (2021) similarly highlight the important role and logic of their institutions to which team members are typically attached.

From an organisational sociology perspective, interpretations of individual actors are shaped by institutional logics and organisational cultures embedded in the broader contexts of the individual collaborators as well as their individual experiences and interests (König 2020). In everyday transdisciplinary research, collaborators have to deal with the heterogeneous and often conflicting ‘institutional logics’ (Thornton and Ocasio 2008, Thornton et al. 2012, Felt et al. 2016, Engels and Walz 2018). Institutional logics, as well as organisational cultures, are defined as the socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, taken for granted assumptions, values and beliefs by which individuals and organisations provide meaning to their day-to-day activities. In addition, prevailing power structures, power dependencies, bureaucratic structures, informal networks or capacities for actions within participating organisations might prove challenging in living lab research (Greenwood and Hinings 1996, Felt et al. 2016). Furthermore, and countering a top-down perspective on institutional logics, the individual interests, values, attitudes, experiences and qualifications of participants enable or constrain collaboration within living labs (Thornton et al. 2012, Binder 2007).

4.1.1. Heterogeneous Interpretations of Living Lab Experimentation

The analysis showed diverse perceptions of the living lab concept as a whole, as well as experimentation. During the interviews in particular, the ideas were sometimes framed as retrospective evaluations or conclusions after describing or reflecting on challenges in day-to-day research. References were generally made to either the testing demands of their roles within the project or their individual attitudes, experiences and interests.

Among all the collaborating actors, the living lab format is predominantly seen as a means of activism to accelerate sustainability transformation. Non-academic and particularly academic actors often emphasised their motivation to make a difference in the real world and their willingness to engage in the project as an agent of sustainability. With regard to academic actors, the concept of a living lab is in contrast sometimes interpreted as merely a fashionable label for what is usually done in applied science anyway. Interviewees with an engineering background in particular conveyed this point of view by referring to the routine implementation of sustainable technology into practice. Less frequently, academic actors adopted a more distanced view, which at the same time marked a rejection of the notion of activism and was more oriented towards the classical research perspective. Therefore, merely observing the transformation and engaging as little as possible is seen as the appropriate approach to research practice. In addition to this orthodox view, critically pessimistic interpretations were also articulated in individual cases. For a few academic actors, the living lab approach represents an overhyped and time-consuming research trend with little impact on sustainability. This view is sometimes also shared by non-academic actors and justified by unfulfilled expectations.

Not fulfilling methodological and epistemological expectations is a central concern of the academic actors in day-to-day research life, manifesting in uncertainties and tensions. Experimentation is therefore described as a continuous process of ‘muddling through’, accompanied by the constant uncertainty of not having guaranteed an appropriate, valid and proper research process – a process characterised by the struggle between freedom and boundaries inherent in questions such as: How should, may or must the test room be designed and controlled? How should the interventions be tested? How should the diverse context be taken into account in the design, evaluation and conclusions of the experiments? How should the established organisational or group rules of the real-life setting be dealt with? These questions remain fairly open even upon completion of the experiments, as do the uncertainties. Feelings of guilt, doubts and self-criticism were often described as familiar sentiments associated with living lab research.

Both academic and non-academic actors often feel overburdened by the expectation to develop successful solutions. However ambiguous or vague the project aims are formulated, the living lab promises actual progress and new solutions. Living up to this ideal, the collaborators tend to produce presentable, successful solutions while concealing the flaws and failures in the experimentation. A number of studies have already pointed to this push towards ‘solutionism’ (Rogga et al. 2018, Huning et al. 2021). Maasen and Lieven explore the ‘pressure management’ that is required in transdisciplinary projects in order to cope with the pressure to produce ‘at least preliminary and always presentable results at all stages of the project’ (Maasen and Lieven 2006: p. 403). Similarly, Engels and Rogge (2018) address tensions arising from the unilateral urge to achieve rapid innovation and economic exploitation within living labs.

4.1.2. Heterogeneous Interpretations and Aspirations of Participation and Co-Creation

Felt et al. (2012: 15) conclude in their study on transdisciplinary sustainability research that ‘scientists do not talk about participation as a single coherent phenomenon’. Similarly, our analysis revealed distinct differences in the individual and collective ideas of participation. It is worth noting that the participants’ own interpretations often contrasted with the ideas expressed by other collaborators or with their former aspirations. As expressions of tensions and conflicts, these juxtapositions often manifest themselves in a polarisation of rather extreme points of view.

The extreme position of ‘obligation of acceptance’ reduces participation to a mere obligation to accept whatever the project or organisational leaders declare as appropriate actions. Put in less drastic terms, this view perceives participation as a means to achieve acceptance from everybody involved. In contrast to this is the opposing extreme position of ‘egalitarianism and heterarchy’, which is an idealistic view held by participants who are eager to co-create. It emphasises a voluntary, non-hierarchical formation of equal partners in any given situation. These extreme positions were problematised mainly by the academic actors. They often position themselves and ‘the others’ within the spectrum between the two poles. In contrast, the non-academic actors display a much less reflective or more passive perspective. This is chiefly explained by the fact that the academic actors consider themselves solely responsible for guaranteeing the principles of participation and co-creation in the research process. The research process is characterised by constant uncertainty from the perspective of the academic actors – every form of collaboration is shaped by the omnipresent question: What kind of participation is ‘right’, ‘appropriate’ or ‘enough’? Similarly, Felt et al. (2013: p. 518) have pointed to the struggle of early-stage researchers ‘to clarify whether or not, or to what degree they are transdisciplinary’.

Uncertainties already arise in seemingly straightforward situations such as the organisation of a workshop or project meeting. Researchers ask themselves questions such as: Should I simply draw up a first proposal myself that can then be discussed, or should I first suggest a joint meeting? Although such uncertainties are usually pushed aside in everyday research in favour of a pragmatic approach (in this case writing a first draft), there remains a constant doubt and a guilty conscience about not fully adhering to the principles of participatory research.

Tensions or conflicts with regard to participation, on the other hand, are more difficult for collaborators to cope with. These arise in more fundamental situations in which essential research decisions are made. In our research case study, the definition of participation that was to form the basis for decisions made within the living lab was not comprehensively clarified at the beginning of or in the course of the research process. As there is no certainty as to what constitutes sufficient participation and as there are no quality criteria in the scientific literature, the participants could rely only on their subjective and situational interpretations. Furthermore, tensions and conflicts tend to be attributed to individual actors who are seen as the cause of these issues. Actors who take a rather heterarchical view tend to find decisions that are not clearly based on consensus problematic. Decisions that are made on the basis of scientific expertise, majority consensus or from a position of power would not be in line with the fundamental principle of participation. The exercise of veto rights accorded by hierarchical positioning (e.g. by project leaders or organisational leaders) is considered particularly problematic. This results in frustrations, tensions or even conflicts over ‘non-participatory’ procedures.

In particular, project and organisational leaders often describe themselves as being forced into an overburdening role in resolving the perceived contradiction between participation and co-creation on the one hand and effectiveness and efficiency on the other. As the individuals primarily responsible for achieving the project objectives, they feel constrained by having to adopt a rather pragmatic view on participation and co-creation. Furthermore, they find themselves confronted with an inherent paradox: On the one hand, the ambiguity of the interpretations of those somewhat abstract ideals results in the aforementioned uncertainties, tensions, frustrations and conflicts in collaboration. On the other hand, this ambiguity allows them to bypass these issues.

However, interpretations of, and particularly aspirations with regard to, participation change over time. Non-academic actors sometimes found themselves overwhelmed by requests for collaboration from the academic actors and became disengaged in the process, causing frustration among academic actors with a rather heterarchical view on participation. Similarly, Felt et al. (2012: p. 14) describe ‘the researchers’ astonishment and disconcertment when extra-scientific partners insist on a work-sharing model instead an integration model’. In addition, some non-academic actors positioned themselves as mere data providers, as they saw no other useful way of participating than by contributing data.

Overall, work-sharing in separated spaces constitutes the main model of collaboration in day-to-day research in our case study. Considering the time constraints, the high demands of daily communication and coordination, and the pressure to deliver results, this model has emerged as viable practice in mitigating challenging reactions. Particularly for academic actors, this mode provides practical benefits. First, it mitigates the risk of the research being too dictated by the demands of the non-academic actors. Second, it encourages disengagement on the part of actors and guards against the views of those who share a rather hierarchical view on participation.

4.2. Heterogeneous Perspectives on Sustainability Interventions

Sustainability and climate protection are emotive and value-laden terms that are often problematised in politicised discussions in everyday research. This was evident in the interviews and especially in the workshops and informal situations. Discussions generally revolved around the question of the appropriateness and legitimacy of sustainability interventions. Fairly polarised conceptions tend to emerge, which can be differentiated according to Weber’s (1947) ideal types of social actions (Starr 1999) and are adopted by both academic and non-academic actors.

On the one hand, there is the value-rational (wertrational) view of sustainability and climate protection, which individual collaborators are guided by and feel committed to in their day-to-day research when developing interventions. According to this normative view, climate protection measures should be implemented quickly, unconditionally and regardless of resistance (‘no delay for climate changes’). The instrumental-rational (zweckrational) view adopts a pragmatic counterposition which states that climate protection measures should be carried out solely on the basis of consideration of the preconditions (‘climate protection takes time’).

The instrumental-rational perspective does not necessarily always correspond to the inner convictions and ambitions of the collaborators. Non-academic actors in particular tend to take greater account of the limitations arising from practical experience (e.g. financial or technological preconditions or cultural aspects) than academic actors. This also includes less willingness to take risks owing to the fact that overly ambitious interventions pose a risk of excessive demands, strains on capacity, and overburdening.

Actors who tend to adopt a value-rational perspective are sometimes impatient in the research process and feel frustrated when measures are not implemented quickly, or ideas are not sufficiently appreciated by others. As a result, ever more tensions arise and sometimes culminate in conflicts when actors are faced with what they perceive to be irresponsible or unproductive resistance from other individuals or groups who slow down the transformation or fail to grasp its necessity. In addition, the noble objective of climate protection provides a justification for increased enforcement of climate action, often causing overburdening, frustrations and disengagement. Similarly, a few studies highlight the implicit normative expectations on sustainability researchers to ‘recognise and accept their social responsibility’ (Cornell et al. 2013: p. 67) and commit themselves to transforming reality (Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014, Salas-Zapatas et al. 2012). Furthermore, in their study on corporate sustainability studies, Van der Byl and Slawinski (2015) identify the potential for diverse understandings of sustainability, individual interests and misbalanced sustainability dimensions to cause conflicts.

4.3. Difficulties in Role Positioning and Allocation

While a few roles were clearly defined and allocated at the beginning at the project (such as gate keepers, project leaders, assessment agents and dissemination agents), the roles of non-academic and academic actors were largely left to fall into place over the course of the project. As the demands of each role emerge, actors seek out their preferred roles or roles are ascribed to other actors – be it mutually or unilaterally or intentionally or unconsciously. Furthermore, roles change over time as a number of studies have highlighted (Wiek 2007, Hilger et al. 2018, Bulten et al. 2021, Arnold 2022, Huning et al. 2021).

In transdisciplinary settings, academic and non-academic actors are inevitably subject to the demands of having to fulfil multiple roles (Stauffacher et al. 2008, Enengel and Muhar 2012, Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014, Hilger et al. 2018, Bulten et al. 2021, Arnold 2022). In their systematic literature, Hilger et al. (2021) identify fifteen roles of academic and non-academic actors assigned to four different realms (field, academia, boundary management and knowledge co-production). They further distinguish the roles as originating from the field (actor groups) or adopted during research process. Mbatha and Musango (2022) explore different stakeholders and their roles in living lab research within the energy sector. Based on an extensive literature analysis, they provide a detailed overview of these actors and their different roles.

Particularly in the case of the academic actors, positioning and fulfilling the multiple associated roles were presented as eminent challenges in everyday research. In the interviews, the academic actors frequently problematised the dual role that they feel they are allowed, pressured or forced to fulfil in the living lab project. This dual role comprises clusters of multiple role responsibilities, some of which are classed as ‘activism’, as distinct from research. Activities such as moderating and coordinating discussions and workshops, and informing, motivating and advising non-academic actors are subsumed under activism. In contrast, the collection, processing and evaluation of data is considered pure research.

Although the majority of the researchers felt that they were well aware of the implications for their own role in view of the requirements for designing a living lab, the challenges only became apparent in the course of the research process. For example, the dual role fundamentally contradicted the self-image of individual academic actors from the outset but was accepted as a small obstacle that could be overcome. As the need for ‘activist’ responsibilities became an ever-greater priority in cooperative experimentation in everyday research, the reluctance of individuals also grew. In extreme cases, research in the living lab is perceived as ‘fake research’. Tensions and even conflicts between academics and non-academics were just as much a consequence of this as frustrations.

Felt et al. (2013, p. 522) describe the transdisciplinary research process as a ‘research borderland’ for academic actors. This conclusion may reflect the strong focus on academic actors in studies of roles in transdisciplinary research, with multiple studies highlighting the struggle of researchers with different roles in this context (Hilger et al. 2018, Arnold 2022). In their study on designing real-world laboratories for sustainable urban transformation, Huning et al. (2021: p. 1599) point to the difficult task actors face in understanding which role to fulfil at a certain moment. By analysing the socialisation of early-stage researchers, Felt et al. (2013: 519) describe the difficulties in developing roles, finding a position and setting up transdisciplinary research lives. Focussing on sustainability transitions, Bulten et al. (2021) analyse the conflicting roles of researchers. They identified five potential roles ranging from ‘reflective scientist’ to ‘transition leader’, and the tensions and conflicts that emerge when combining roles. Tensions arise from ‘three underlying sources: (1) researchers’ self-perception and expectations, (2) expectations of transdisciplinary partners, funders and researchers’ home institutions and (3) societal convictions about what scientific knowledge is and how it should be developed’ (Bulten et al. 2021). In a similar way, Pajot et al. (2024) analysed how researchers adopt multiple and changing roles in sustainability science projects in France. They explore the influence of stakeholder engagement, the need for role flexibility and adaptability of researchers as well as a need to tailor roles to project characteristics.

In our research case study, the need for role flexibility and adaptability of researchers was problematised as somewhat limitless during the interviews. Only a ‘jack-of-all-trades’ could possibly handle all the demands of the roles at hand. First, this points to the lack of skills all actors attribute to themselves and other collaborators. The skills necessary for multiple roles often extend the skills needed in traditional empirical research (cf. Huning et al. 2021: 1599). Similarly, Wiek et al. (2011) highlight the researchers’ lack of skills and identified five key competencies which should be combined and integrated. Second, this is indicative of the uncertainties and frustrations in everyday research, particularly in the context of general time constraints. Third, this points to the willingness to adapt to unfamiliar roles. Several studies have highlighted personality as a potential driver of researchers’ roles (Pajot et al. 2024, Miah et al. 2015). Each of the three aspects increases the risk of disengagement on the part of either academic or non-academic actors.

4.4. Emergence of Instrumentalisation and Over-Identification

Joint interactions in the living lab often evoke familiarity and mutual empathy between the collaborators over time. This process was described by all interviewees as a positive development for collaboration in everyday research. This closer rapport and mutual empathy among the cooperation partners can also prove to be disadvantageous. Both academic and non-academic actors reported frustrations, tensions and sometimes conflicts as a result of situations they felt were instrumentalised by their collaborators.

Instrumentalisation should not be understood as having exclusively negative connotations. First, particular roles within the living lab are usually already allocated during the design phase. Roles such as gate keepers, dissemination agents and communicators were assigned or at least predefined in our case. Second, academic actors willing to embrace their activist role complaisantly perceive themselves as service providers for the non-academic partners. Felt et al. (2012: p. 18) report an identical observation in their study on participation in sustainability research projects.

In our case, the challenges of instrumentalisation relate mainly to the relationship between academic and non-academic actors. Situations were recounted in which tasks or responsibilities were passed on to ‘the others’ – or unsuccessful attempts to do so were made. At the same time, instrumentalisation is attributed to individuals on both sides, around whom tensions then revolve. The fact that mere attempts at reallocation are being problematised illustrates a particular awareness or even alert stance among each actor’s groups. At the same time, all collaborators are exposed to a lack of resources and time constraints (Felt et al. 2012), which legitimises the reallocation of tasks the further the research project progresses.

The emergence of instrumentalisation often appears to be accompanied by a process labelled as ‘going native’. This term, as used within ethnography and anthropology, is the phenomenon of losing one’s research role and becoming totally immersed in the culture or group of people with whom one is collaborating (Madden 2010, Hanson, 2018). This goes beyond the perceptions mentioned above of academic actors as service providers. In rare cases, they see themselves rather as members of the non-academic groups or organisation. Similarly, Hilger et al. (2021) identify instances of the researchers adopting roles from the field as a step beyond the duality of practitioner and researcher.

Furthermore, most academic actors consciously allow themselves to be instrumentalised and used strategically for the project aims and the real-life setting. Legitimising interventions or problematizing sensitive issues is broadly seen as a mandatory function to fulfil. Likewise, Marg and Theiler (2023: p. 641) point to the legitimizing role of researchers and their instrumentalisation by the municipal administration within the transdisciplinary project.

4.5. Embedded Complexities Of Living Lab Governance

Like the research process as a whole, living lab governance was overly problematised as a process of ‘muddling through’ the difficulties in everyday research. In principle, and in line with the concept of participation, the governance as well as the creation of the living lab infrastructure is a joint endeavour. The way in which responsibility for governing the living lab project is distributed is therefore shaped by the modes of participation that the actors intentionally or unintentionally created.

Governance represents the culmination of challenging reactions in collaboration. First, heterogeneous interpretations of key living lab concepts, heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, difficulties in role positioning and allocation, and the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification might be considered as failed management on the part of the project leaders. In our case study, and as highlighted above, challenging reactions were sometimes attributed to individual leaders. Second, reactions such as tensions and conflicts call for mitigation measures, which themselves might account for uncertainties or overburdening. Third, both academic and non-academic actors identified a vast series of difficulties – all broadly related to the proto-challenges described above. These difficulties can be categorised based on varying core requirements in day-to-day practice.

Managing participation and co-creation:

Unfamiliarity with and lack of experience of project management built on the principles of transdisciplinarity and participation

Difficulties in balancing and integrating the different interpretations of key concepts as well as aspirations of sustainability

Difficulties in balancing and integrating the different disciplinary and real-life setting perspectives (cf. Nesti 2017).

Managing needs, ideals, roles and expectations:

Permanent need for project adaptation with multiple actors and organisations

Balancing expectations (e.g. on participation, innovation and results) with practical conditions and possibilities

Balancing conflicting ideals and practical needs

Balancing the need for creative freedom with the need to reduce complexity

Managing limitations, openness and unknowns:

Lack of resources and time constraints in general (cf. Felt et al. 2012)

Difficulty in maintaining conceptional openness to new topics in the research process alongside the demands for stability and predictability in the living lab

Difficulty in dealing with the effects of unintended interventions or unforeseen external events (e.g. crises and political and regulative changes) on the experiments

One additional challenge emerged over the extended course of the project. Due to their aim of enabling sustainable innovation, living labs are often designed as a long-term initiative over several years (Veeckman et al. 2013). In our case study, the timespan for the long lab was initially set for three years and was subsequently extended for a further two years. The long duration of the project and the diversity of the players involved are also accompanied by a natural fluctuation of collaborators. Numerous academic and non-academic collaborators had to be newly recruited during the process. Engels and Rogge (2018) explore the challenge of integrating new participants into the living lab and the risk of destabilizing established actor dynamics.

5. Discussion

In our analysis, we identified uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts and disengagement as challenging reactions in everyday living lab collaboration as well as symptoms of five interrelated proto-challenges: (1) heterogeneous interpretations of key living lab concepts, (2) heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, (3) difficulties in role positioning and allocation, (4) the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and the culmination of these challenges leading to complexities in living lab governance. We argue that these proto-challenges are constitutive and implicitly inscribed into the key design principles of sustainability living lab research.

First, the proto-challenges thrive on the fertile ground of diverse institutional logics, power structures and dependencies, organisational structures, networks and capacities for actions (Greenwood and Hinings 1996, Lang et al. 2012, Felt et al. 2016). Second, when viewing living labs as transformation infrastructures, collaborative innovation is constrained or facilitated by ‘constitutive tensions’ (Schikowitz et al. 2023). Referring to the concepts of continuity and contingency, they describe inevitable political, ideological and epistemic tensions in synthesizing traditions (conventions, perspectives and knowledge) and innovations (disruption and inclusion) into the infrastructures of living labs. Comprising organisational, material, technical and symbolic aspects, the living lab infrastructures are ‘permanently institutionalised and innovated’ (Schikowitz et al. 2023: p. 63). Felt et al. (2012) similarly identified tensions inherent in participatory research in an earlier study on sustainability research. From this perspective, living lab governance is equally subject to the same polarity.

We highlighted the often polarised interpretations of key concepts such as participation, experimentation and co-creation, the difficulties in role positioning and allocation, and the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification. The everyday governance of living labs can be considered a constant attempt to cope with the embeddedness of complexities and challenging reactions.

Following the thesis that constitutive tensions ‘cannot be resolved but must be processed’ (Schikowitz et al. 2023: p. 62), the question arises as to which coping strategies should be applied. Based on our case study and recommendations in scientific literature on challenges in transdisciplinary research, we distinguish between three ‘ideal-typical’ coping strategies categorised according to their mode of action: mitigate, embrace and tolerate. In the following, we describe the strategies according to their function, application and risk.

Figure 3.

Overview – Proto-challenges, challenging reactions and coping strategies.

Figure 3.

Overview – Proto-challenges, challenging reactions and coping strategies.

Mitigate Challenges

The mitigation approach focuses on preventing challenging reactions as well as proto-challenges by employing design and management tools that address the governance or infrastructure of the living lab. A vast number of studies examining challenges, barriers and tensions in sustainability and transdisciplinary research provide recommendations or guidelines for mitigation. Examples include general design principles (Lang et al. 2012, Nesti 2017), principles for balancing team compositions (Boon et al. 2014), skills (Wiek et al. 2014), roles (Hessels at al. 2018, Adelle et al. 2019), coping strategies for conflicts (Van der Byl and Slawinski 2015) and quality or evaluation criteria (Jahn and Keil 2015, Blackstock et al. 2007). Mitigation measures favour consensus, harmony and compromises, demanding awareness and resources at the same time. Both aspects are often outsourced to external experts providing feedback such as coaching or supervision (Schaffers et al. 2009, Wirth et al. 2019). By privileging continuity over contingency, mitigating strategies carry the risk of limiting innovation.

Embrace Challenges

This approach stems from the perspective that certain tensions cannot be resolved but need to be embraced permanently (Engels and Rogge 2018, Scoones and Stirling 2020, Schikowitz et al. 2023). The embracement view emphasises the constructive possibilities of contingencies as a source of innovation and represents a paradoxical approach which accepts and explores tensions rather than resolutions (Arnold 2022). Indeed, it encourages actors to ‘host the tensions and the associated inconsistencies’ (Engels and Rogge 2018: 31). As a rather unintuitive strategy, it allows for contingencies and dissonance, perhaps even provoking unplanned encounters, settings, irritations or confrontations. Sufficient awareness among the actors and transparent proceedings and resources are prerequisites of this approach. By privileging contingency over continuity, embracing strategies carry the risk of destructive escalation or withdrawal.

Tolerate Challenges

The tolerance approach emphasises an alert stance towards challenges without taking countering or embracement measures. This strategy encourages letting things go in a rather Zen-like way. This does not mean ignoring or neglecting challenges, but engaging with them by recognizing them without the immediate urge to take actions. Similar to the embracement approach, this strategy unintuitively accepts irresolvable contradictions and allows for ‘agonism’ (Schikowitz et al. 2023, Björgvinsson et al. 2012, Farías and Blok 2016, Farías and Widmer 2017, Karvonen A and Van Heur 2014). It should be emphasised that this strategy should not be misunderstood as a consequence of disengagement by living lab actors. Like the embracement approach, it too allows for contingencies and dissonance. In addition to sufficient awareness, the approach requires tolerance for organisational slack as well as joint understanding on why mitigation measures are not taken. Tolerating challenges and reactions carries the risks of both alternative approaches – limiting innovation and enabling destructive escalation or withdrawal.

6. Conclusions

Sustainability research addresses the complexities of the significant challenges facing contemporary societies (Felt et al. 2012). As a tool for sustainability, living lab research challenges given assumptions, imaginations and expectations on the part of collaborators. Challenging reactions such as uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts and disengagement are an inevitable part of everyday collaboration in living labs. These are emphatically an inherent tendency given the heterogeneous interpretations of key living lab concepts, the heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, the difficulties in role positioning and allocation, the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and the embedded complexities of living lab governance which both constrain and enable innovation.

Coping with these (proto-)challenges can appear a daunting task. Mitigating challenges and reactions carries the risk of limiting innovation, embracing tensions carries the risk of destructive escalation, while tolerance involves both risks. Wicked problems are defined as impossible to solve because of incomplete, ambiguous, contradictory and fluctuating demands. We might say that collaborative sustainability research in living labs is in itself a wicked problem.

No unqualified recommendations can therefore be made for practical application. If anything, our study points to the need for awareness, preparation and resilience on the part of living lab research actors with respect to the constitutive challenges of collaboration. We highlight the possibilities of the somewhat unintuitive coping strategies of embracing and tolerating constitutive challenges. Both strategies would undermine the ‘tendency towards continuity’ of academic actors that Schikowitz et al. (2023: p. 71) identify in their study of two living labs on urban mobility in Austria. Embracing and tolerating contingencies are unintuitive approaches and require effort, transparent processes and a joint understanding. We further argue with Schikowitz et al. that ‘meeting the various demands and expectations that policy makers and researchers amount on living labs is, in fact, a mission impossible’ (2023: p. 72). Hence, our results may foster a knowledge and understanding of the unavoidable challenges in everyday living lab research.

In considering heterogeneous interpretations of key living lab concepts and heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions as inevitable, as well as a source of contingencies and innovation, we find ourselves caught in a dilemma. On the one hand, we would be keen to argue for further scientific research on quality standards for the design and implementation of living lab infrastructures and governance. On the other hand, the harmonising or standardisation of living lab infrastructures as a mitigation-tool would prevent the contingencies needed for innovation.

The limitations of our study are primarily epistemological. First, our single-case design challenges the potential for generalisations as we assume constitutive proto-challenges as typical of living lab research. By relating our results to other contemporary studies, we have attempted to provide validity for our arguments beyond our case study. Nevertheless, additional investigations into multiple case studies are strongly recommended. Future studies should focus notably on differences in project characteristics as sampling criteria. Second, our involvement as researchers as well as collaborators carries the risk of biased interpretations. The support or assignment of external researchers in future work would mitigate that risk and yet at the same time limit the opportunities for participation in everyday living lab practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, W.K.; methodology, W.K. and L.S.; validation, W.K., formal analysis, W.K.; investigation, W.K and L.S.; resources, S.L.; data curation, W.K and L.S..; writing—original draft preparation, W.K. and L.S..; writing, review and editing, W.K.; visualisation, W.K.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Science, Research and Art of the German Federal State Baden-Württemberg within the scope of the research project ‘Klima RT Lab’. All conclusions, errors or oversights are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adelle, C., Pereira, L., Görgens, T., & Losch, B. (2019). Making sense together: The role of scientists in the coproduction of knowledge for policy making. Science and Public Policy.

- Al-Chalabi, M. (2013). Targeted and Tangential Effects – A Novel Framework for Energy Research and Practitioners. Sustainability, 15, 12864. [CrossRef]

- Almirall, E., & Wareham, J. (2010). Living Labs: Arbiters of Mid- and Ground-Level Innovation. In W. van der Aalst, J. Mylopoulos, N. M. Sadeh, M. J. Shaw, C. Szyperski, I. Oshri, & J. Kotlarsky (Eds.), Global Sourcing of Information Technology and Business Processes (Vol. 55, pp. 233–249). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Arnold, M. G. (2022). The challenging role of researchers coping with tensions, dilemmas and paradoxes in transdisciplinary settings. Sustainable Development, 30(2), 326–342. [CrossRef]

- Bakıcı, T., Almirall, E., & Wareham, J. (2013). A Smart City Initiative: The Case of Barcelona. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 4(2), 135–148. [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P., & Schuurman, D. (2015). Living Labs: Concepts, Tools, and Cases. Info, 17. [CrossRef]

- Baran, G., & Berkowicz, A. (2020). Sustainability Living Labs as a Methodological Approach to Research on the Cultural Drivers of Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 12(12), 4835. [CrossRef]

- Barth, M., Jiménez-Aceituno, A., Lam, D. P. M., Bürgener, L., & Lang, D. J. (2023). Transdisciplinary Learning as a Key Leverage for Sustainability Transformations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 64, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B., Ihlström Eriksson, C., & Ståhlbröst, A. (2015). Places and Spaces Within Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review, 5, 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Bernert, P., Wahl, D., von Wehrden, H., et al. (2023). Cross-Case Knowledge Transfer in Transformative Research: Enabling Learning in and Across Sustainability-Oriented Labs Through Case Reporting. Urban Transformations, 5, 12. [CrossRef]

- Binder, A. (2007). For Love and Money: Organizations' Creative Responses to Multiple Environment Logics. Theoretical Sociology, 36, 547-571.

- Björgvinsson, E., Ehn, P., & Hillgren, P. A. (2012). Agonistic Participatory Design: Working With Marginalised Social Movements. CoDesign, 8(2-3), 127-144.

- Blackstock, K. L., Kelly, G. J., & Horsey, B. L. (2007). Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecological Economics, 60, 726–742.

- Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. University of California Press.

- Boon, W. P. C., Hessels, L. K., & Horlings, E. (2019). Knowledge co-production in protective spaces: Case studies of two climate adaptation projects. Regional Environmental Change, 1–13.

- Brankaert, R., den Ouden, E., & Brombacher, A. (2015). Innovate dementia: The development of a living lab protocol to evaluate interventions in context. Info, 17(4), 40–52. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S., Büscher, C., & Hessels, L. K. (2017). Towards transdisciplinarity: A water research programme in transition. Science and Public Policy, 45(2), 211–220.

- Bulten, E., Hessels, L. K., Hordijk, M., & Segrave, A. J. (2021). Conflicting Roles of Researchers in Sustainability Transitions: Balancing Action and Reflection. Sustainability Science, 3(6), 949. [CrossRef]

- Canzler, Weert; Engels, Franziska; Rogge, Caniglia, G.; Schäpke, N.; Lang, D.L.; Abson, D.J.; Luederitz C.; Wiek, A.; Laubichler, M.D.; Gralla, F.; Von Wehrden, H., (2017): Experiments and evidence in sustainability science: A typology, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 69. [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V.; Bulkeley, H., (2013): A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Glob Environ Chang, 3(1), 92–102. [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C. Free for All. Wicked problems. Manag. Sci. (1967): 14, B141–B142.

- Cornell, S., Berkhout, F., Tuinstra, W., Tabara, J. D., Jaeger, J., Chabay, I., De Wit, B., Langlais, R., Mills, D., Moll, P., Otto, I. M., Petersen, A., Pohl, C., & Van Kerkhoff, L. (2013). Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environmental Science & Policy, 28, 60–70.

- Creswell, John W. (2009): Research design. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3. ed., [Nachdr.]. Los Angeles, Calif.: Sage.

- Defila, R.& Di Giulio, A. (2019). Eine Reflexion über Legitimation, Partizipation und Intervention im Kontext transdisziplinärer Forschung. In M. Ukowitz und R. Hübner (Eds.), Interventionsforschung. Band 3: Wege der Vermittlung. Intervention - Partizipation. (pp. 85-108). Springer.

- Dekker, R., Franco Contreras, J.; Meijer, A. (2020): The Living Lab as a Methodology for Public Administration Research: a Systematic Literature Review of its Applications in the Social Sciences. In: International Journal of Public Administration 43 (14), S. 1207–1217. [CrossRef]

- Di Giulio, A., Defila, R., & Brückmann, T. (2016). „Das ist halt das eine … Praxis, das andere ist Theorie“ – Prinzipien transdisziplinärer Zusammenarbeit im Forschungsalltag. In R. Defila & A. Di Giulio (Eds.), Transdisziplinär forschen. Zwischen Ideal und gelebter Praxis; Hotspots, Geschichten, Wirkungen (pp. 189–286). Campus Verlag.

- Enengel, B., & Muhar, A. (2012). Co-Production of Knowledge in Transdisciplinary Doctoral Theses on Landscape Development—An Analysis of Actor Roles and Knowledge Types in Different Research Phases. Landscape and Urban Planning, 105(1–2), 106–117.

- Engels Krohn, W., & Weyer, J. (1994). Society as a laboratory: The social risks of experimental research. Science and Public Policy, 21(3), 173–183.

- Engels, A.; Rogge, J. C., (2018): Tensions and Trade-offs in Real-World Laboratories – The Participants' Perspective, Gaia, Vol. 27(S1), 28-31, MUNICH: oekom verlag.

- European Comission (2022): Launch event of Flagship 7 of the European Commission’s Zero Pollution Action Plan. Brussels, 2022. Online verfügbar unter https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/living-labs-heart-zero-pollution-action-plan.

- Farías, I., & Blok, A. (2016). Technical democracy as a challenge to urban studies. City, 20(4), 539-548.

- Farías, I., & Widmer, S. (2017). Ordinary smart cities: How calculated users, professional citizens, technology companies, and city administrations engage in a more-than-digital politics. Tecnoscienza, 8(2), 43-60.

- Felt, U., Igelsböck, J., Schikowitz, A., & Völker, T. (2012). Challenging Participation in Sustainability Research. DEMESCI: International Journal of Deliberative Mechanisms in Science, 1(1), 4-34. [CrossRef]

- Felt, U., Igelsböck, J., Schikowitz, A., & Völker, T. (2013). Growing into what? The (un-)disciplined socialisation of early stage researchers in transdisciplinary research. Higher Education, 65(4), 511–524. [CrossRef]

- Feurstein, K.; Hesmer, A.; Hribernik, Karl; Thoben, Klaus-Dieter; Schumacher, Jens (2008): Living Labs – A New Development Strategy. In:, S. 1–14.

- Følstad, A. (2008). Towards a living lab for development of online community services. Electronic Journal of Virtual Organisations, 10, 47–58.

- Frank, H., Korunka, C., Lueger, M., & Sammer, D. W. (2016). Intrapreneurship education in the dual education system. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Venturing, 8(4), Article 82218, 334. [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N., & De Haan, H. (2009). Transitions: Two steps from theory to policy. Futures, 41(9), 593–606.

- Froschauer, U., & Lueger, M. (2020). Das qualitative Interview: Zur Praxis interpretativer Analyse sozialer Systeme (2nd, fully revised and expanded ed.). Facultas. https://elibrary.utb.de/doi/book/10.36198/9783838552804.

- Giddens, A. (2009). The politics of climate change (1st ed.). Polity Press.

- Gonser, M., Eckart, J., Eller, C., Köglberger, K., Häußler, E., & Piontek, F. M. (2019). Unterschiedliche Handlungslogiken in transdisziplinären und transformativen Forschungsprojekten – Welche Risikokulturen entwickeln sich daraus und wie lassen sie sich konstruktiv einbinden? In R. Defila & A. Di Giulio (Eds.), Transdisziplinär und transformativ forschen (Band 2, pp. 39–83). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Greenwood, R.; Hinings, C. R., (1996): Understanding radical organizational change: Bringing together the Old and the New Institutionalism, Academy of Management Review, 21, 1022-1054.

- Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C.; Sahlin, K.; Suddaby, R., (2013): The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. SAGE Publications Ltd.: London.

- Groß, M. (2005). Realexperimente: Ökologische Gestaltungsprozesse in der Wissensgesellschaft (1st ed.). Transcript Verlag. https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9783839403044.

- Hakkarainen, L., & Hyysalo, S. (2013). How do we keep the living laboratory alive? Learning and conflicts in living lab collaboration. Technology Innovation Management Review, 3(12), 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Hanson, A. J. (2018). "Going Native": Indigenizing ethnographic research. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 38(2), 83-99.

- Hessels, L.K.; De Jong, S.P.L.; Brouwer, S., (2018): Collaboration between Heterogeneous Practitioners in Sustainability Research: A Comparative Analysis of Three Transdisciplinary Programmes, Sustainability, 10, 4760. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M., Leminen, S., & Westerlund, M. (2019). A systematic review of living lab literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 213, 976–988. [CrossRef]

- Hilger, A., Rose, M., & Wanner, M. (2018). Changing Faces—Factors Influencing the Roles of Researchers in Real-World Laboratories. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 27(2), 138–145.

- Hilger, A., Rose, M., & Keil, A. (2021). Beyond Practitioner and Researcher: 15 Roles Adopted by Actors in Transdisciplinary and Transformative Research Processes. Sustainability Science, 16, 2049–2068. [CrossRef]

- Huning, S., Räuchle, C., & Fuchs, M. (2021). Designing real-world laboratories for sustainable urban transformation: Addressing ambiguous roles and expectations in transdisciplinary teams. Sustainability Science, 16, 1595–1607. [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T., & Keil, F. (2015). An actor-specific guideline for quality assurance in transdisciplinary research. Futures, 65, 195–208.

- Karvonen, A., & Van Heur, B. (2014). Urban laboratories: Experiments in reworking cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(2), 379-392.

- König, W., 2020: Energy efficiency in industrial organizations – A cultural-institutional framework of decision making. Energy Research & Social Science, Vol. 60. [CrossRef]

- Laakso, S., Heiskanen, E., Matschoss, K., Apajalahti, E.-L., & Fahy, F. (2021). The role of practice-based interventions in energy transitions: A framework for identifying types of work to scale up alternative practices. Energy Research & Social Science, 72, 101861. [CrossRef]

- Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., et al. (2012). Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science: Practice, Principles, and Challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(Suppl 1), 25–43. [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S., Westerlund, M., & Nyström, A.-G. (2012). Living labs as open-innovation networks. Technology Innovation Management Review, 2, 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S., Nyström, A.-G., & Westerlund, M. (2015a). A typology of creative consumers in living labs. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 37. [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S., DeFillippi, R., & Westerlund, M. (2015b). Paradoxical tensions in living labs. In XXVI ISPIM Conference – Shaping the Frontiers of Innovation Management. Budapest, Hungary, 14–17 June.

- Maasen, S., & Lieven, O. (2006). Transdisciplinarity: A new mode of governing science? Science and Public Policy, 33(6), 399-410.

- Madden, R. (2010). Being ethnographic: A guide to the theory and practice of ethnography. London, England: SAGE.

- Marg, O.; Theiler, L., (2023): Effects of transdisciplinary research on scientific knowledge and reflexivity. Research Evaluation, 2023, 32, 635–647. [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, S. P., & Musango, J. K. (2022). A systematic review on the application of the living lab concept and role of stakeholders in the energy sector. Sustainability, 14(21), 14009. [CrossRef]

- Miah, J. H., Griffiths, A., McNeill, R., Poonaji, I., Martin, R., Morse, S., Yang, A., & Sadhukhan, J. (2015). A small-scale transdisciplinary process to maximizing the energy efficiency of food factories: Insights and recommendations from the development of a novel heat integration framework. Sustainability Science, 10, 621–637.

- Miebach, B. (2006). Soziologische Handlungstheorie: Eine Einführung (2nd, revised and updated ed.). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Nesti, G. (2017). Living labs: A new tool for co-production? In A. Bisello, D. Vettorato, R. Stephens, & P. Elisei (Eds.), Smart and sustainable planning for cities and regions (pp. 267–281). Springer International Publishing.

- Pajot, G., Bergerot, B., Dufour, S., et al. (2024). The diversity of researchers’ roles in sustainability science: The influence of project characteristics. Sustainability Science, 19, 1963–1977. [CrossRef]

- Pryshlakivsky, J., & Searcy, C. (2013). Sustainable development as a wicked problem. In S. F. Kovacic & A. Sousa-Poza (Eds.), Managing and engineering in complex situations (Vol. 21, pp. 109–128). Springer Netherlands.

- Puerari, E., de Koning, J., von Wirth, T., Karré, P., Mulder, I., & Loorbach, D. (2018). Co-creation dynamics in urban living labs. Sustainability, 10(6), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Rogga, S., Zscheischler, J., & Gaasch, N. (2018). How much of the real-world laboratory is hidden in current transdisciplinary research? GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 27, 18–22. [CrossRef]

- Romero Herrera, N. (2017). The emergence of living lab methods. In D. V. Keyson, O. Guerra-Santin, & D. Lockton (Eds.), Living Labs (pp. 9–22). Springer International Publishing.

- Salas-Zapata, W. A., Rios-Osorio, L. A., & Trouchon-Osorio, A. L. (2012). Typology of scientific reflections needed for sustainability science development. Sustainability Science. [CrossRef]

- Schaffers, H., C. Merz and J. G. Guzman, "Living labs as instruments for business and social innovation in rural areas," (2009): IEEE International Technology Management Conference (ICE), Leiden, Netherlands, 2009, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Schikowitz, A., Maasen, S., & Weller, K. (2023). Constitutive Tensions of Transformative Research: Infrastructuring Continuity and Contingency in Public Living Labs. Science and Technology Studies, 36(3). [CrossRef]

- Schultze, U., & Boland, R. J., Jr. (2000). Place, space and knowledge work: A study of outsourced computer systems administrators. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 10(3), 187–219. [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I., & Stirling, A. (2020). The politics of uncertainty: Challenges of transformation. London: Routledge.

- Sengers F.; Wieczorek, A.J.; Raven, R., (2019): Experimenting for sustainability transitions: a systematic literature review. Technol Forecast Soc Chang., 145, 153–64. [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Houghton Mifflin. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy1105/2001131551-d.html.

- Simon, J.-C. D., & Wentland, A. (2017). From “living lab” to strategic action field: Bringing together energy, mobility, and information technology in Germany. Energy Research & Social Science, 27, 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Osborn, J.; Martiskainen, M.; Lipson, M. Testing smarter control and feedback with users: Time, temperature and space in household heating preferences and practices in a Living Laboratory. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 65, 102185.

- Starr, B. E. (1999). The Structure of Max Weber’s Ethic of Responsibility. The Journal of Religious Ethics, 27(3), 407–434. [CrossRef]

- Stauffacher, M., Flüeler, T., Krütli, P., & Scholz, R. W. (2008). Analytic and Dynamic Approach to Collaboration: A Transdisciplinary Case Study on Sustainable Landscape Development in a Swiss Pre-Alpine Region. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 21(6), 409–422. [CrossRef]

- Thollander, P., Palm, J., & Hedbrant, J. (2019). Energy efficiency as a wicked problem. Sustainability, 11(6), 1569. [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P. H.; Ocasio, W. (2008): Institutional Logics. In: Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C.; Sahlin, K.; Suddaby, R., 2013: The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, 99- 129.

- Thornton, P. H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M., (2012): The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process. OUP Oxford.

- Van der Byl, C. A., & Slawinski, N. (2015). Embracing tensions in corporate sustainability: A review of research from win-wins and trade-offs to paradoxes and beyond. Organization & Environment, 28(1), 54–79.

- Veeckman, C., Schuurman, D., Leminen, S., & Westerlund, M. (2013). Linking Living Lab Characteristics and Their Outcomes: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Technology Innovation Management Review, 3(12), 6-15. http://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/748.

- von Wirth, T., Fuenfschilling, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Coenen, L. (2019). Impacts of urban living labs on sustainability transitions: Mechanisms and strategies for systemic change through experimentation. European Planning Studies, 27(2), 229–257. [CrossRef]

- Waes van, A.; Nikolaeva, A.; Raven, R., (2021): Challenges and dilemmas in strategic urban experimentation An analysis of four cycling innovation living labs, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Volume 72,121004. [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. (1947). Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft (Vol. 2). P. Siebeck: Tübingen.

- Westerlund, M., & Leminen, S. (2011). Managing the challenges of becoming an open innovation company: Experiences from living labs. Technology Innovation Management Review, 1(1), 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A. (2007). Challenges of transdisciplinary research as interactive knowledge generation—Experiences from transdisciplinary case study research. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, 16(1), 52–57.

- Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218.

- Wittmayer, J. M., & Schäpke, N. (2014). Action, research and participation: Roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustainability Science, 9(4), 483–496.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).