1. Importance

PARP-1 is required for NF-κB to activate the expression of inflammatory and immune response genes. NF-κB is also an important transcription factor in HIV-1 gene expression during active replication and latency reactivation. Enhancing NF-κB signaling is expected to cause HIV-1 latency reactivation, but significant systemic side effects related to the NF-κB role in inflammatory and immune responses are predictable. The role of PARP-1 in NF-κB-mediated activation of HIV-1 gene expression and in viral infection has not been determined in the context of HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells. Our data indicate that PARP-1 is dispensable for NF-κB-mediated activation of HIV-1 gene expression in a human CD4+ T lymphoblastoid cell line. These findings suggest that the pharmacological antagonism of PARP-1 could diminish the inflammatory effects of latency-reactivating agents that activate NF-κB signaling without impairing their effect on HIV-1 gene expression.

2. Introduction

HIV cure requires the removal of the latently infected reservoir (1, 2). Transcriptional regulation of proviruses is central to any strategy of eliminating the functional reservoir (3). Among the different signaling pathways regulating HIV-1 transcription, the NF-κB pathway is very relevant in latency establishment and reversal (4, 5). However, because of the essential role of NF-κB regulation in the expression of inflammatory and other immune response genes (6), interventions that trigger HIV-1 transcription in an NF-κB-dependent manner are expected to cause severe inflammation and immune activation (4, 7-14)

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), an enzyme implicated in multiple cellular processes, including the regulation of transcription (15, 16), modulates NF-κB activity through both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms. This functional interaction regulates the transcription of a wide variety of host genes implicated in inflammation and immune activation (17-22). PARP-1 is the most enzymatically active member of the PARP family, promoting the transfer of ADP ribose molecules from NAD+ to acceptor proteins or to an existing poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) chain (23). This post-translational modification alters the function of target proteins by changing their subcellular localization, molecular interactions, and enzymatic activities. Additionally, catalytic-independent functions have been demonstrated to mediate the PARP-1 biological activities (16, 23-26).

PARP-1 stimulates NF-κB signaling through its coactivator function in response to inflammatory stimuli, and via the atypical NF-κB signaling pathway activated by DNA damage (27). As a coactivator, PARP-1 promotes the interaction of NF-κB with the basal transcription machinery (17, 18, 28), whereas, in response to DNA damage, PARP-1 facilitates the nuclear localization of NF-κB (4, 6, 28). Additionally, through PARylation, PARP-1 enhances the activity of NF-κB (12, 29).

In contrast to the well-established role of PARP-1 in the transcriptional regulation of inflammation and immune activation genes, its function in HIV-1 gene expression is a matter of debate. Different functions of PARP-1 suggest its implication in HIV-1 gene expression (18, 30, 31). At the level of transcriptional initiation, PARP-1 could modulate the activity of several transcription factors or the chromatin structure at the viral promoter (3). PARP-1 has been reported to regulate the activity of NF-κB, AP-1, Sp1, and NFAT (19, 32), which are implicated in the transcription of HIV-1 (3). In particular, NF-κB and Sp1 are crucial for viral transcription, while AP-1 and NFAT play more modulatory roles. NF-κB is sufficient to activate LTR transcription and its activity is potentiated by Sp1 and AP-1 (3). Furthermore, PARP-1 has been reported to enhance Tat activity in an LTR reporter in HeLa cells (33).

In correlation with a positive role of PARP-1 in the activity of NF-κB in the context of the HIV-1 promoter, PARP-1 inhibition has been reported to decrease HIV mRNA levels and virus production in the chronically infected human pro-monocyte U1 cell line stimulated with the NF-κB activator Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (30). Additionally, transient PARP-1-KD in Jurkat and HeLa cells, and PARP-1 inhibition in human monocyte-derived macrophages reduced HIV-1 LTR reporter activation triggered by compounds that activate NF-κB signaling (18, 30, 31, 34). In contrast to this positive role in NF-κB-mediated HIV-1 LTR transcription, Vpr, which facilitates HIV-1 replication in T cells and is required for optimal infection of human monocyte-derived macrophages, has been reported to retain PARP-1 in the cytosol, impairing NF-κB-mediated transcription of a non-viral promoter (35).

To better understand the role of PARP-1 in NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 gene expression, we investigated the impact of NF-κB signaling on HIV-1 proviral gene expression in PARP-1-knockout (KO) human CD4+ T cell line (SUP-T1) and HEK 293T cells. Our results demonstrate that PARP-1 deficiency does not impair HIV-1 infection or gene expression and is not essential for NF-κB-mediated HIV-1 transcription. Interestingly, PARP-1 KO significantly disrupted NF-κB-driven activation of the promoter of the inflammatory gene inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). These findings suggest that targeting PARP-1 may reduce the inflammatory response associated with the use of latency-reactivating agents that activate the NF-κB signaling pathway.

3. Materials and Methods

PARP-1 knockout (KO) and backcomplemented (BC) cell lines: The generation and characterization of PARP-1 KO and backcomplemented cell lines was described in (39). Briefly, SUP-T1 and HEK 293T cells were transduced with an HIV-1-derived viral vector expressing a zinc-finger nuclease targeting PARP-1, and selected in the presence of puromycin. The lack of PARP-1 expression was verified by immunoblot, and single-cell KO clones were selected. To generate the backcomplemented counterpart, these clones were transduced with a Murine Leukemia Virus-derived viral vector expressing PARP-1, and then selected in the presence of G418. PARP-1 re-expression was verified by immunoblot.

Generation of lentiviruses. The replication-defective, HIV-1 reporter viruses were produced by calcium-phosphate transfection of HEK 293T as previously described (64). Briefly, cells were co-transfected with the HIV-1 transfer plasmid (15 ug), the HIV-1 packaging plasmid pCMVΔR8.91 (15 ug), and the plasmid pMD.G (5 ug) encoding the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus glycoprotein G. The HIV-1 reporter NLENG1-ES-IRES (65) is env deleted and expresses LTR-driven eGFP from the nef slot, and Nef from an IRES. The HIV-1 reporter Hluc expresses LTR-driven luciferase from the nef slot and contains a large deletion in env (40). This virus also lacks the expression of Vpr and Nef. HlucΔκβ was derived from Hluc by mutating the two LTR NF-κB binding sites. To this end, PCR-mediated mutagenesis was performed with reverse primer EF3 (5’-ggaaagtagattgtagcaagctcgatgtcagcagttc-3’, target sequence 5’-gaactgctgacatcgagcttgctacaatctactttcc-3’) and forward primer EF4 (5’-gctgtctactttccagggaggcgtggcctgggcgggactggggag-3’) using Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Thermo Scientific catalog # F-541), as described in (64). The mutations introduced have been reported to ablate the two copies of the enhancer κB elements implicated in NF-κB binding to the LTR (46), and are indicated in the primers with bolded and underlined font.

Single-round infection analysis. PARP-1 KO and BC SUP-T1- and HEK 293T-derived cell lines were plated at a density of 01.X106 cells in 500 µl of culture medium per well in 24-well plates and infected with the non-replicating viruses. Cells infected with viruses expressing luciferase were typically harvested four days after infection and analyzed for luciferase activity with a luminescence kit (Bright-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System, Promega, E2620) as described in (64). In some experiments, ATP was measured in the same samples using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, G7570) to normalize for cell number and viability. Cells infected with the HIV-1 reporter expressing eGFP were analyzed by flow cytometry four days after infection.

Effect of different stimuli on HIV-1 infection. HIV-1-infected SUP-T1 PARP-1 KO and BC cells (2x105 cells / 300 µl) were subjected to different stimuli for three days and then luciferase levels were measured. The stimuli were TNF-α (10 ng/ml), anti-CD3/CD28 immunobeads (1 bead per cell, Dynabeads® Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 for T Cell Expansion and Activation, catalog number 11161D), and PMA (10 ng/ml). In some experiments, cells were treated with the NF-κB signaling inhibitor BAY-11-7082 (3 µM) one hour before TNF-α stimulation. Then the inhibitor was kept for the entire duration of the experiment.

Long-term HIV-1-infected SUP-T1 PARP-1 KO and BC cells (2x105 cells / 300 µl) were treated with sodium butyrate (5 mM; B5887; Sigma) for 24 h or with 5-azacytidine (30 and 10 µM; A2385; Sigma) for 36 h. Following these treatments, the cells were analyzed for luciferase and ATP levels. Luciferase levels were normalized to ATP levels to account for any potential effect of these treatments on cell viability.

Effect of TNF-α on the activity of the iNOS promoter. PARP-1 KO and BC HEK 293T cells were calcium-phosphate co-transfected with a CMV-driven β-galactosidase expression plasmid [pCMV-β-gal, (66)] and iNOSpWT-luciferase or iNOSpΔNFκB-luciferase reporter plasmid (49). Transfected cells were subjected to different treatments, and β-galactosidase and luciferase were measured three days later. β-galactosidase was measured with the Beta-Glo assay system (Promega, E4720). Luciferase levels were normalized to β-galactosidase activity to control for transfection efficiency.

The iNOS reporters were previously described (49). The reporter iNOSpWT-luciferase contains a 1516-base pair fragment that includes 1485 and 31 nucleotides upstream and downstream, respectively, of the transcription start site of the mouse iNOS gene. The NF-κB site (−85 to −83 nucleotides) was mutated (GGG to CTC) in iNOSpWT-luciferase to generate iNOSpΔNFκB-luciferase.

4. Results

HIV-1 infection is not impaired in PARP-1-KO human CD4+ T lymphoblastoid cells. Several reports indicate that PARP-1 deficiency does not affect the infectivity of VSV-G pseudotyped, single-round infection HIV-1 (36-38), suggesting that PARP-1 does not affect HIV-1 gene expression. Importantly, in only one of these publications (37), experiments were conducted in cells of a histological origin relevant to HIV-1 infection in vivo, meaning in a human CD4+ T cell line (SUP-T1). However, an important caveat in this research was that the cells studied were only partially deficient in PARP-1. To use a more robust cellular model, we evaluated the role of PARP-1 in HIV-1 gene expression, and in particular in NF-κB regulation of the HIV-1 LTR, in PARP-1 knockout cells derived from the human CD4+ T cell line SUP-T1, and their backcomplemented counterpart (39).

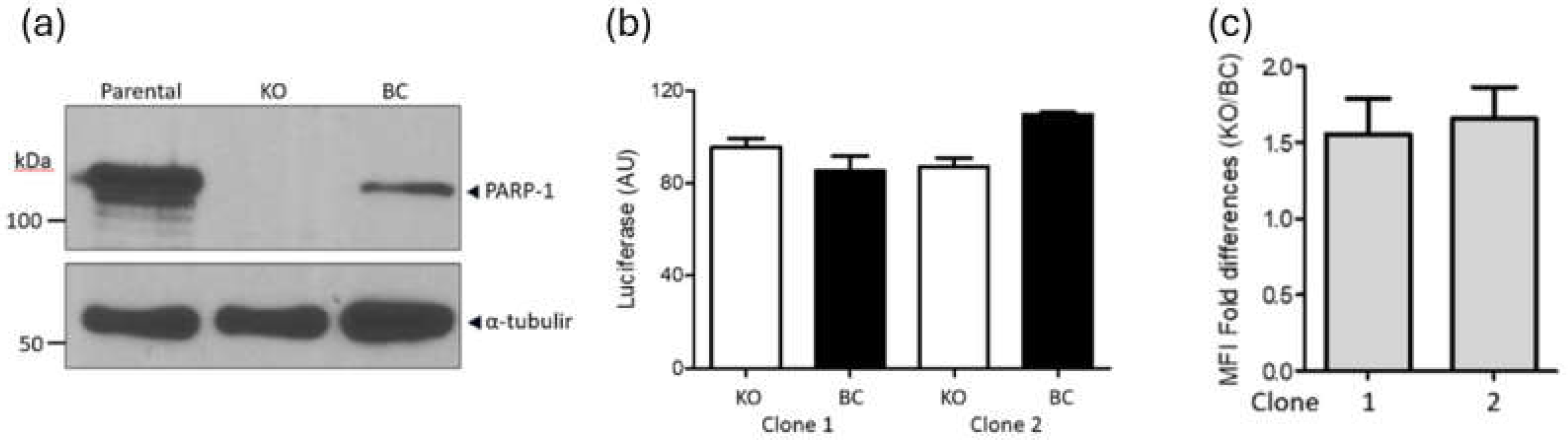

PARP-1 KO and BC SUP-T1 cells (

Figure 1a) were infected with a single-round infection, VSV-G pseudotyped HIV-1

NL4-3 and luciferase levels were measured four days later. This reporter virus is mutated in the

env,

nef and

vpr genes, and expresses LTR-driven luciferase from the

nef slot (Hluc) (40, 41). In correspondence with previous findings (37, 39), PARP-1 levels did not significantly influence HIV-1 transgene expression (

Figure 1b). KO cells expressed luciferase at 1.1-fold (clone 1) and 0.8-fold (clone 2) of the levels observed in the corresponding BC clones, indicating that PARP-1 has no significant effect on HIV-1 infection or gene expression.

We also evaluated the effect of PARP-1 deficiency on the infection and gene expression of an HIV-1

NL4-3-derivative that expresses eGFP from the viral promoter. PARP-1-KO and -BC clones were infected with this virus and analyzed by FACS four days later (

Figure 1c). eGFP mean fluorescence intensity was 1.5 +/- 0.5 and 1.6 +/- 0.6 higher in PARP-KO clones 1 and 2, respectively, than in their corresponding BC cell lines, demonstrating further that PARP-1 is dispensable for LTR-driven transcription.

PARP-1 is dispensable in NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 gene expression. PARP-1 is required in NF-κB-dependent expression of multiple pro-inflammatory genes (19, 27, 42, 43) and genes activated

by CD3/CD28 signaling in lymphocytes (19, 32). In contrast, PARP-1 seems to be dispensable for the transcriptional activity of the HIV-1 LTR (

Figure 1), which is an NF-κB-responsive promoter. This potential dichotomy is important since the undesired inflammatory response is a relevant side effect of HIV-1 latency reactivation strategies targeting NF-κB.

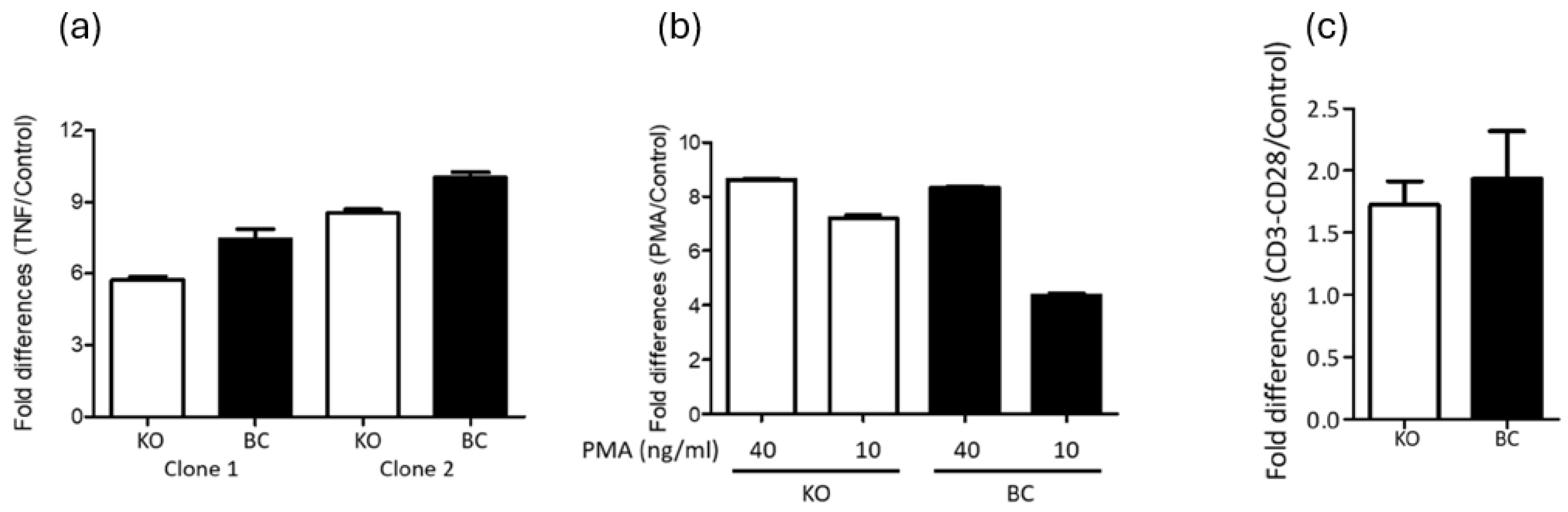

To assess the potential dispensability of PARP-1 in NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression, Hluc-infected PARP-1 knockout (KO) and BC SUP-T1 cells were cultured for three weeks to eliminate unintegrated HIV-1 cDNA. The cells were then stimulated with the NF-κB activators tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α, 10 ng/mL) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 40 and 10 ng/mL). Three days post-stimulation, luciferase expression was measured to evaluate transcriptional activity.

TNF-α (

Figure 2a) equivalently increased luciferase expression in both PARP-1 KO and BC SUP-T1 infected cells. In clone 1, TNF-α increased luciferase 5.7 (KO cells) and 7.4 folds (BC cells). Similarly, in clone 2 the increase was 8.5- and 10-fold in KO and BC cells, respectively. Therefore, activation was only 1.3 (clone 1) and 1.2 (clone 1) higher in BC than in KO SUPT1 cells.

PMA similarly activated the HIV-1 LTR in PARP-1 KO and BC SUPT1 cells (

Figure 2b). At 40 ng/ml, PMA caused 8.6- and 8.3-fold activation in clone 1 KO and BC cells, respectively. Meanwhile, at 10 ng/ml PMA activated the HIV-1 LTR by 7.2-fold and 4.4-fold in KO and BC SUP-T1 cells, respectively. These results reaffirming that PARP-1 is not required for PMA activation of the HIV-1 LTR promoter.

HIV-infected PARP-1 KO and -BC SUP-T1 cells were also stimulated by anti-CD3/-CD28 crosslinking that activates NFκB, AP-1, and NFAT signaling pathways

(19, 32). CD3/CD28 stimulation activated HIV-1 gene expression by 1.7- and 1.9-fold in PARP-1 KO and BC SUP-T1 cells (

Figure 2c). These findings also indicated a negligible role of PARP-1 in the regulation of the HIV-1 promoter through these transcription factors.

TNF-α is expected to stimulate the HIV-1 LTR promoter via NF-κB signaling (44). To verify the implication of this mechanism, PARP-1 KO and BC SUPT1 cells were infected with Hluc, and 4 days later the cells were stimulated for 3 days with TNF-α (10 ng/ml) in the presence or no of BAY-11-7082 (BAY). This compound inhibits the TNF-α-induced phosphorylation of IκB-α, preventing NF-κB nuclear translocation (45).

To exclude treatment toxicity, we first evaluated the effect of 3-day BAY treatment on the viability of SUP-T1 cells, measured as ATP levels. At 10 µM and 5 µM the compound was very toxic, and cell viability dropped to 2% +/- 4.4% and 57% +/- 12.6%, respectively, the viability of control cells treated with DMSO. However, at 3 µM and 2 µM, cell viability was 80% +/- 10.4% and 83% +/-13.5%, respectively, the viability of DMSO-treated cells. Therefore, we used BAY at 3 µM in subsequent studies.

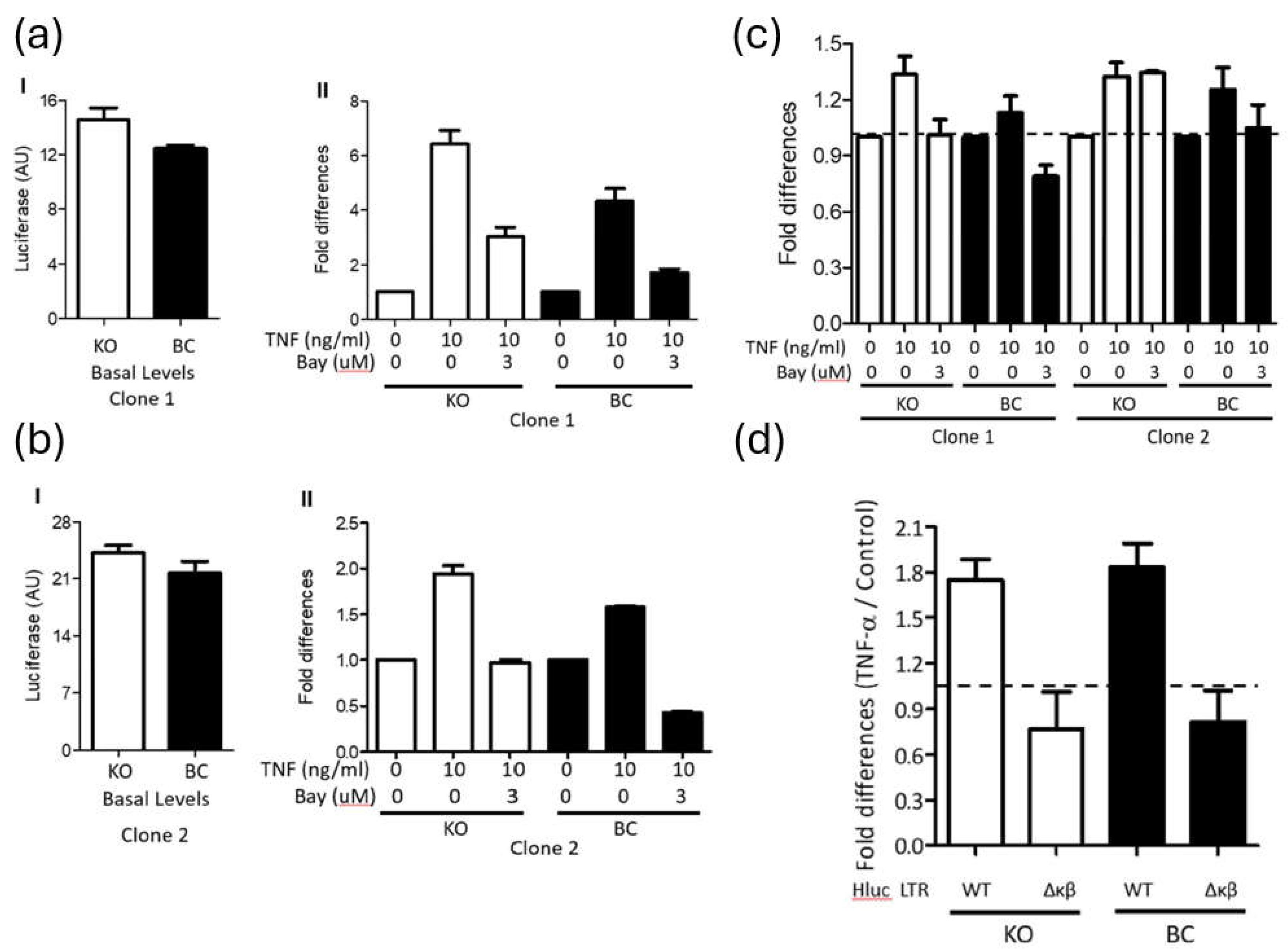

As shown before, basal levels of luciferase were similar in non-treated PARP-1 KO and BC SUPT1 clones 1 (Fig.3a I) and 2 (Fig.3a II), and these values were used for normalization of the luciferase levels found in the corresponding cells upon TNF-α stimulation. Notably, luciferase expression was upregulated by TNF-α stimulation in both PARP-1 KO (6.4 and 1.9 folds, clones 1 and 2) and BC (4.3 and 1.6 folds, clones 1 and 2) SUPT1 cells (Fig.3a). Furthermore, BAY blocked the stimulatory effect of TNF-α with equivalent potency in both PARP-1 KO (2.1 and 2 folds, clones 1 and 2) and BC (2.5 and 3.7 folds, clones 1 and 2) SUPT1 cells (

Figure 3a I - II). These findings indicated that NF-κB mediates TNF-α-induced activation of the HIV-1 promoter, regardless of PARP-1 cellular levels.

The viability of the cells studied in

Figure 3a was determined by measuring their ATP levels. The basal ATP levels of untreated cells were used to normalize the ATP measurements in their corresponding treated counterparts. Data in

Figure 3b indicate no important differences in cell viability. ATP levels only decreased, to 79% of control values, in PARP-1 BC clone 1 following treatment with TNF-α and BAY. These results confirmed that the reduction in HIV-1 transgene expression induced by BAY was not attributable to cell toxicity.

To further demonstrate that in these cells TNF-α induced HIV-1 gene expression through NF-κB signaling, PARP-1 KO and BC SUP-T1 cells were infected with Hluc carrying an NF-κB mutant (Hluc

Δκβ) or wild-type LTR. Hluc

Δκβ lacks the two copies of the enhancer κB elements implicated in NF-κB binding (46). Cells were stimulated or not with TNF-α at day four post-infection, and three days later; luciferase levels were determined. As shown before (

Figure 2a and

Figure 3a), TNF-α activated luciferase expression with a similar magnitude in PARP-1 KO (1.7 folds) and BC (1.8 folds) SUPT1 cells (

Figure 3c). However, TNF-α failed to activate LTR-driven transcription (< 1-fold) in cells infected with Hluc

Δκβ, independently of the PARP-1 levels in these cells (

Figure 3c). Therefore, TNF-α stimulated HIV-1 gene expression in PARP-1 KO cells in an NF-κB-dependent manner.

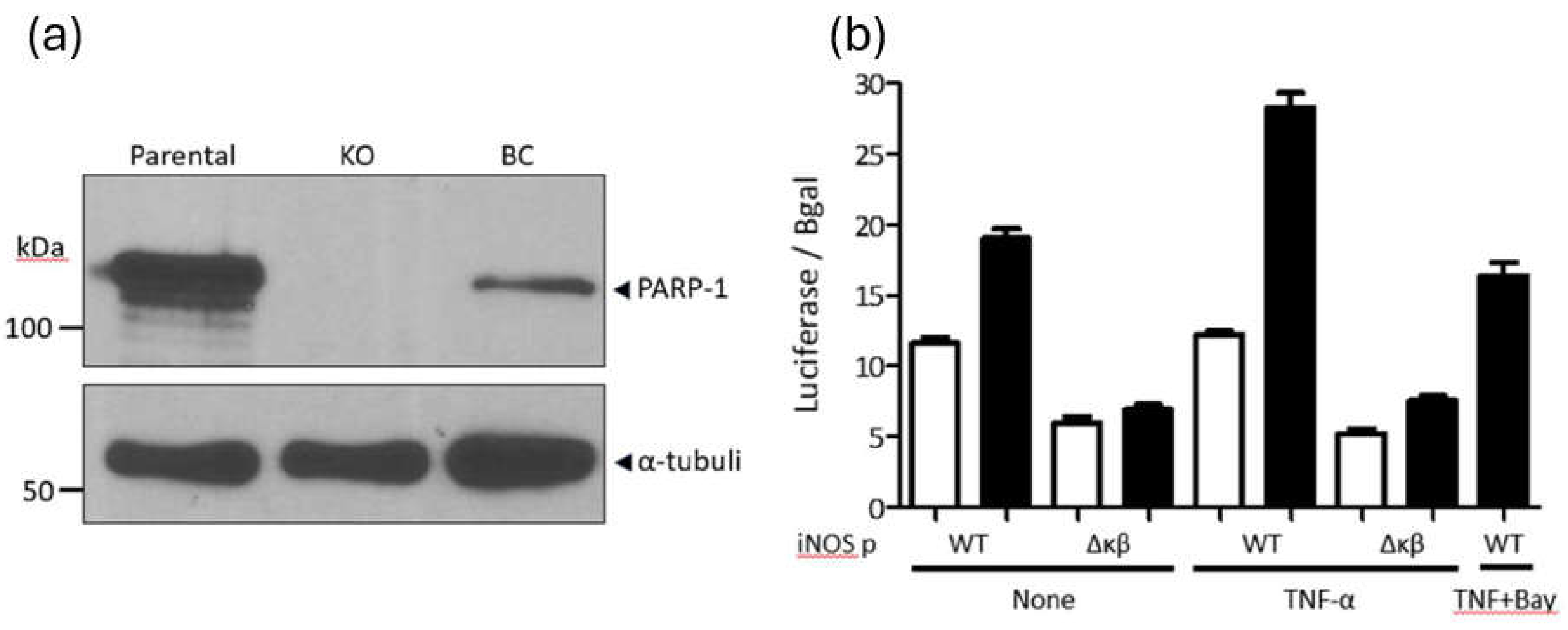

PARP-1 is required in the NF-κB-dependent expression of the inflammatory gene inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS). As mentioned above, PARP-1 is required for NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activation of inflammatory genes, such as iNOS (47, 48). Therefore, as a control, we evaluated the requirement of PARP-1 in NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activation of the iNOS promoter. To this end, we used PARP-1 KO and BC HEK 293T cells (39) due to their high transfection efficiency. PARP-1 KO and BC HEK 293T cells (

Figure 4a) were co-transfected with a CMV-driven β-galactosidase expression plasmid (transfection control) along with a plasmid encoding a luciferase reporter whose expression is driven by the iNOS promoter wild-type (iNOSp WT) or a mutant promoter lacking the NF-κB-binding site (iNOSpΔNFκB) (49). Two days after transfection, the cells were divided into different groups and treated with vehicle (basal conditions), TNF-α, and TNF-α + BAY. Twenty-four hours later, luciferase and β-galactosidase activity were measured. Luciferase values were normalized to β-galactosidase activity to account for transfection efficiency.

In correspondence with previous reports (47, 48), the basal expression of the iNOSpWT-luciferase plasmid was 1.6 folds lower in HEK 293T PARP-1 KO than in BC cells (

Figure 4b). In contrast, the basal expression of iNOSpΔNFκB-luciferase was similar in both cell lines but 1.9-fold lower in KO cells and 2.7-fold lower in BC cells compared to the expression driven by iNOSpWT (

Figure 4b). Furthermore, TNF-α activated iNOSpWT-luciferase in the HEK 293T PARP-1 BC cells (1.5 folds) but failed to stimulate this promoter in the PARP-1 KO cells. Furthermore, TNF-α treatment also failed to activate iNOSpΔNFκB-luciferase in both PARP-1 KO and BC HEK 293T cells (

Figure 4b). The activating effect of TNF-α on iNOSpWT-luciferase was entirely inhibited by BAY in PARP-1 BC cells (

Figure 4b), indicating the NF-κB-dependency of this observation.

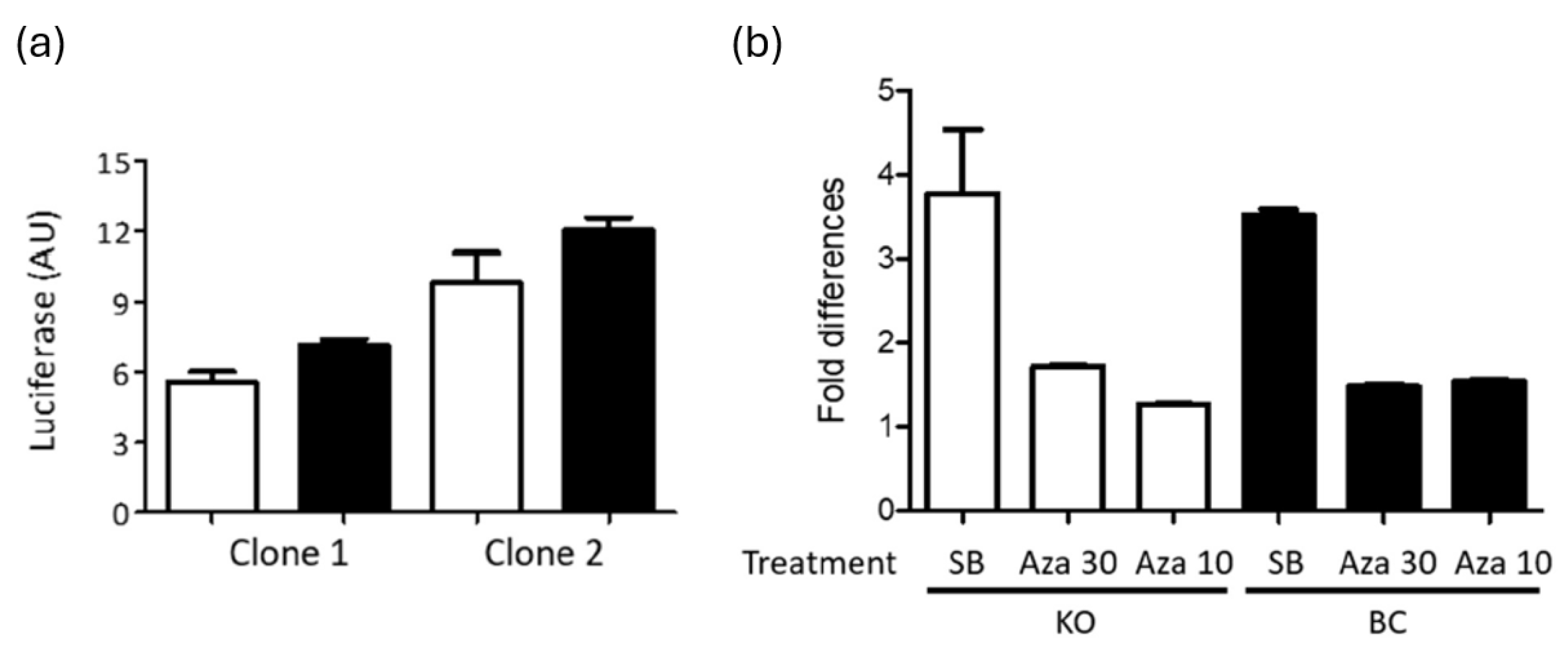

PARP-1 does not affect HIV-1 LTR silencing. PARP-1 has been proposed as a required cofactor for HIV-1 integration in the centromeric region (50). HIV-1 integration in centromeric region is disfavored (51, 52) and has been associated to the latent reservoir (53, 54). Therefore, we evaluated the temporal stability of gene expression of the HIV-1 provirus in SUPT1 cells expressing or no PARP-1. Hluc-infected SUPT-1 PARP-1 KO and BC cells were cultured for one month and luciferase expression was measured. Notoriously, HIV-1 gene expression was similar in cells expressing or no PARP-1 after prolonged cell culture (

Figure 5a), suggesting an equivalent tendency of HIV-1 proviruses to gene silencing in these cells.

Furthermore, these long-term infected cells were stimulated with sodium butyrate (SB, 5 mM) or 5-Azacytidine (Aza, 30 and 10 uM), known epigenetic modulators that activate silenced HIV-1 proviruses (55). ATP was measured in the treated cells to verify the preservation of the cell viability upon treatment, and ATP values were used to normalize the luciferase activity in these cells. SB was more potent activator than Aza in both cell lines, and both compounds similarly enhanced HIV-1 gene expression in PARP-1 KO and BC SUPT1 cells (

Figure 5b), indicating that these compounds activate HIV-1 gene expression independently of PARP-1. Furthermore, this data suggested that the size of the HIV-1 silenced reservoir susceptible to reactivation with these epigenetic modifiers is similar in both cell lines.

5. Discussion

NF-κB signaling is critical in the expression of inflammatory and immune genes (17-22), and in the transcriptional activity of the HIV-1 promoter during latency reactivation and active viral replication. Therefore, HIV-1 latency reactivation agents acting through NF-κB signaling are expected to trigger important inflammatory and immune reactions, limiting their clinical value. PARP-1 is required for NF-κB-mediated induction of inflammatory and immune genes (17-22). However, the role of PARP-1 in HIV-1 gene expression is debatable, and its requirement for NFκB-induced HIV-1 gene expression is ill-defined.

Our results indicate that PARP-1 is dispensable for basal or NF-κB-induced HIV-1 gene expression in a human CD4+ T cell line. These findings contradict reports indicating a positive or negative role of PARP-1 in HIV-1 transcription. In non-infected cells, PARP-1 has been reported to enhance HIV-1 LTR-mediated reporter gene expression under basal conditions (33) and upon stimulation with NF-κB-inducers (18, 30, 31, 34). In contrast with this positive role in HIV-1 transcription, PARP-1 has also been reported to negatively regulate the HIV-1 promoter when evaluated using LTR- reporter systems (56-59). These contradictions highlight important differences in the regulation of the HIV-1 LTR promoter when presented as a plasmid or as a provirus.

Our data in CD4+ T cells are also in contradiction with findings in cells of myeloid origin. PARP-1 inhibition was found to decrease HIV mRNA levels in the chronically infected human pro-monocyte U1 cell line stimulated with the NF-κB-inducer, PMA (30). This contradiction adds further evidence to the previously described differences in HIV-1 promoter activity in T cells and macrophages (60, 61).

In conclusion, we found that PARP-1 does not influence NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 gene expression in a human CD4+ T cell line. This is in marked contrast to the required role of PARP-1 in TNF-α-induced, NFκB-dependent activation of pro-inflammatory gene promoters (19, 27, 42, 43). The differential role of PARP-1 on HIV-1 and pro-inflammatory gene promoters illustrates the reported exquisite specificity of NF-κB signaling (62, 63). That is, NF-κB allows, for the same stimulus, to differentially modulate promoters with different requirements of transcription factors, co-activators, and co-repressors. Therefore, due to differences in promoter architecture, PARP-1 could play unique roles in NF-κB-dependent activation of HIV-1 LTR and pro-inflammatory gene promoters. Our findings further suggest that PARP-1 antagonism could reduce the pro-inflammatory effects of HIV-1 latency reactivation agents acting via NF-κB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Number SC1GM115240 to ML from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH). We thank the Biomolecule, Genomic Analysis and the Cellular Characterization, and Biorepository Core Facilities for technical help. These core facilities are supported by a Research Centers in Minority Institutions program grants 5G12MD00759 and 2U54MD007592 to the Border Biomedical Research Center in UTEP from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, a component of NIH.We thank David N. Levy (New York University, Dental Center) for providing the HIV-1 reporter plasmid NLENG1-ES-IRES, Mark A. Perrella (Harvard Medical School) for providing the iNOSpΔNFκB- and iNOSpWT-luciferase reporter plasmids, and Elias Farran (UTEP) for generating the HlucΔκβ mutant.

References

- Trono D, Van Lint C, Rouzioux C, Verdin E, Barre-Sinoussi F, Chun TW, Chomont N. HIV persistence and the prospect of long-term drug-free remissions for HIV-infected individuals. Science 329:174-80. [CrossRef]

- Siliciano RF. What do we need to do to cure HIV infection. Top HIV Med 18:104-8. [CrossRef]

- Dutilleul A, Rodari A, Van Lint C. 2020. Depicting HIV-1 Transcriptional Mechanisms: A Summary of What We Know. Viruses 12.

- Wong LM, Jiang G. 2021. NF-kappaB sub-pathways and HIV cure: A revisit. EBioMedicine 63:103159.

- Nixon CC, Mavigner M, Sampey GC, Brooks AD, Spagnuolo RA, Irlbeck DM, Mattingly C, Ho PT, Schoof N, Cammon CG, Tharp GK, Kanke M, Wang Z, Cleary RA, Upadhyay AA, De C, Wills SR, Falcinelli SD, Galardi C, Walum H, Schramm NJ, Deutsch J, Lifson JD, Fennessey CM, Keele BF, Jean S, Maguire S, Liao B, Browne EP, Ferris RG, Brehm JH, Favre D, Vanderford TH, Bosinger SE, Jones CD, Routy JP, Archin NM, Margolis DM, Wahl A, Dunham RM, Silvestri G, Chahroudi A, Garcia JV. 2020. Systemic HIV and SIV latency reversal via non-canonical NF-kappaB signalling in vivo. Nature 578:160-165.

- Vanden Berghe W, Ndlovu MN, Hoya-Arias R, Dijsselbloem N, Gerlo S, Haegeman G. 2006. Keeping up NF-kappaB appearances: epigenetic control of immunity or inflammation-triggered epigenetics. Biochem Pharmacol 72:1114-31. [CrossRef]

- Ke R, Conway JM, Margolis DM, Perelson AS. 2018. Determinants of the efficacy of HIV latency-reversing agents and implications for drug and treatment design. JCI Insight 3. [CrossRef]

- Baker RG, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. 2011. NF-kappaB, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab 13:11-22.

- Catrysse L, van Loo G. 2017. Inflammation and the Metabolic Syndrome: The Tissue-Specific Functions of NF-kappaB. Trends Cell Biol 27:417-429.

- Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. 2017. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2:17023-.

- Capece D, Verzella D, Flati I, Arboretto P, Cornice J, Franzoso G. 2022. NF-kappaB: blending metabolism, immunity, and inflammation. Trends Immunol 43:757-775.

- Wasyluk W, Zwolak A. 2021. PARP Inhibitors: An Innovative Approach to the Treatment of Inflammation and Metabolic Disorders in Sepsis. J Inflamm Res 14:1827-1844. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Wang B, Liu X, Deng Y, Zhu Y, Zhu F, Liang Y, Li H. 2021. Sp1 Targeted PARP1 Inhibition Protects Cardiomyocytes From Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via Downregulation of Autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol 9:621906. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Huang K, Li X, Du M, Kang X, Luo X, Gao L, Wang C, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Tong Q, Huang K, Zhang F, Huang D. 2013. Identification of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 as a cell cycle regulator through modulating Sp1 mediated transcription in human hepatoma cells. PLoS One 8:e82872. [CrossRef]

- Ji Y, Tulin AV. 2010. The roles of PARP1 in gene control and cell differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20:512-8. [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar R, Kraus WL. 2010. The PARP side of the nucleus: molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Mol Cell 39:8-24. [CrossRef]

- Hassa PO, Haenni SS, Buerki C, Meier NI, Lane WS, Owen H, Gersbach M, Imhof R, Hottiger MO. 2005. Acetylation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 by p300/CREB-binding protein regulates coactivation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription. J Biol Chem 280:40450-64.

- Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. 1999. A role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. Biol Chem 380:953-9. [CrossRef]

- Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. 2002. The functional role of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 as novel coactivator of NF-kappaB in inflammatory disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci 59:1534-53. [CrossRef]

- Zhang JN, Ma Y, Wei XY, Liu KY, Wang H, Han H, Cui Y, Zhang MX, Qin WD. 2019. Remifentanil Protects against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation through PARP-1/NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway. Mediators Inflamm 2019:3013716.

- Kraus WL, Lis JT. 2003. PARP goes transcription. Cell 113:677-83. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap P, Szabo C. 2005. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and the therapeutic effects of its inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:421-40. [CrossRef]

- Ame JC, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. 2004. The PARP superfamily. Bioessays 26:882-93.

- Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. 2005. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1: 'PAR-laying' NAD+ into a nuclear signal. Genes Dev 19:1951-67. [CrossRef]

- Kotova E, Jarnik M, Tulin AV. 2010. Uncoupling of the transactivation and transrepression functions of PARP1 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:6406-11. [CrossRef]

- Wacker DA, Ruhl DD, Balagamwala EH, Hope KM, Zhang T, Kraus WL. 2007. The DNA binding and catalytic domains of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 cooperate in the regulation of chromatin structure and transcription. Mol Cell Biol 27:7475-85. [CrossRef]

- Oliver FJ, Menissier-de Murcia J, Nacci C, Decker P, Andriantsitohaina R, Muller S, de la Rubia G, Stoclet JC, de Murcia G. 1999. Resistance to endotoxic shock as a consequence of defective NF-kappaB activation in poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 deficient mice. EMBO J 18:4446-54. [CrossRef]

- Weaver AN, Yang ES. 2013. Beyond DNA Repair: Additional Functions of PARP-1 in Cancer. Front Oncol 3:290. [CrossRef]

- Bohio AA, Sattout A, Wang R, Wang K, Sah RK, Guo X, Zeng X, Ke Y, Boldogh I, Ba X. 2019. c-Abl-Mediated Tyrosine Phosphorylation of PARP1 Is Crucial for Expression of Proinflammatory Genes. J Immunol 203:1521-1531. [CrossRef]

- Kameoka M, Tanaka Y, Ota K, Itaya A, Yoshihara K. 1999. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase is involved in PMA-induced activation of HIV-1 in U1 cells by modulating the LTR function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 262:285-9. [CrossRef]

- Rom S, Reichenbach NL, Dykstra H, Persidsky Y. 2015. The dual action of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase -1 (PARP-1) inhibition in HIV-1 infection: HIV-1 LTR inhibition and diminution in Rho GTPase activity. Front Microbiol 6:878. [CrossRef]

- Saenz L, Lozano JJ, Valdor R, Baroja-Mazo A, Ramirez P, Parrilla P, Aparicio P, Sumoy L, Yelamos J. 2008. Transcriptional regulation by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 during T cell activation. BMC Genomics 9:171. [CrossRef]

- Yu D, Liu R, Yang G, Zhou Q. 2018. The PARP1-Siah1 Axis Controls HIV-1 Transcription and Expression of Siah1 Substrates. Cell Rep 23:3741-3749. [CrossRef]

- Kameoka M, Nukuzuma S, Itaya A, Tanaka Y, Ota K, Ikuta K, Yoshihara K. 2004. RNA interference directed against Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 efficiently suppresses human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human cells. J Virol 78:8931-4. [CrossRef]

- Muthumani K, Choo AY, Zong WX, Madesh M, Hwang DS, Premkumar A, Thieu KP, Emmanuel J, Kumar S, Thompson CB, Weiner DB. 2006. The HIV-1 Vpr and glucocorticoid receptor complex is a gain-of-function interaction that prevents the nuclear localization of PARP-1. Nat Cell Biol 8:170-9. [CrossRef]

- Ariumi Y, Turelli P, Masutani M, Trono D. 2005. DNA damage sensors ATM, ATR, DNA-PKcs, and PARP-1 are dispensable for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integration. J Virol 79:2973-8. [CrossRef]

- Bueno MT, Reyes D, Valdes L, Saheba A, Urias E, Mendoza C, Fregoso OI, Llano M. 2013. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 promotes transcriptional repression of integrated retroviruses. J Virol 87:2496-507. [CrossRef]

- Siva AC, Bushman F. 2002. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 is not strictly required for infection of murine cells by retroviruses. J Virol 76:11904-10. [CrossRef]

- Martinez ZS, Gutierrez DA, Valenzuela C, Seong CS, Llano M. 2024. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 regulates HIV-1 replication in human CD4+ T cells. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Llano M, Saenz DT, Meehan A, Wongthida P, Peretz M, Walker WH, Teo W, Poeschla EM. 2006. An essential role for LEDGF/p75 in HIV integration. Science 314:461-4. [CrossRef]

- Connor RI, Chen BK, Choe S, Landau NR. 1995. Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mononuclear phagocytes. Virology 206:935-44. [CrossRef]

- Majewski PM, Thurston RD, Ramalingam R, Kiela PR, Ghishan FK. 2010. Cooperative role of NF-{kappa}B and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) in the TNF-induced inhibition of PHEX expression in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 285:34828-38.

- Ha HC. 2004. Defective transcription factor activation for proinflammatory gene expression in poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1-deficient glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:5087-92. [CrossRef]

- Hiscott J, Kwon H, Genin P. 2001. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Clin Invest 107:143-51. [CrossRef]

- Novis CL, Archin NM, Buzon MJ, Verdin E, Round JL, Lichterfeld M, Margolis DM, Planelles V, Bosque A. 2013. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 in central memory CD4(+) T cells through TLR-1/2 stimulation. Retrovirology 10:119.

- Chen BK, Feinberg MB, Baltimore D. 1997. The kappaB sites in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat enhance virus replication yet are not absolutely required for viral growth. J Virol 71:5495-504. [CrossRef]

- Nakajima H, Nagaso H, Kakui N, Ishikawa M, Hiranuma T, Hoshiko S. 2004. Critical role of the automodification of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent gene expression in primary cultured mouse glial cells. J Biol Chem 279:42774-86. [CrossRef]

- Naura AS, Datta R, Hans CP, Zerfaoui M, Rezk BM, Errami Y, Oumouna M, Matrougui K, Boulares AH. 2009. Reciprocal regulation of iNOS and PARP-1 during allergen-induced eosinophilia. Eur Respir J 33:252-62. [CrossRef]

- Perrella MA, Pellacani A, Wiesel P, Chin MT, Foster LC, Ibanez M, Hsieh CM, Reeves R, Yet SF, Lee ME. 1999. High mobility group-I(Y) protein facilitates nuclear factor-kappaB binding and transactivation of the inducible nitric-oxide synthase promoter/enhancer. J Biol Chem 274:9045-52. [CrossRef]

- Kameoka M, Nukuzuma S, Itaya A, Tanaka Y, Ota K, Inada Y, Ikuta K, Yoshihara K. 2005. Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 is required for integration of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome near centromeric alphoid DNA in human and murine cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334:412-7. [CrossRef]

- Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. 2002. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell 110:521-9. [CrossRef]

- Carteau S, Hoffmann C, Bushman F. 1998. Chromosome structure and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA integration: centromeric alphoid repeats are a disfavored target. J Virol 72:4005-14. [CrossRef]

- Jordan A, Bisgrove D, Verdin E. 2003. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. Embo J 22:1868-77. [CrossRef]

- Jiang C, Lian X, Gao C, Sun X, Einkauf KB, Chevalier JM, Chen SMY, Hua S, Rhee B, Chang K, Blackmer JE, Osborn M, Peluso MJ, Hoh R, Somsouk M, Milush J, Bertagnolli LN, Sweet SE, Varriale JA, Burbelo PD, Chun TW, Laird GM, Serrao E, Engelman AN, Carrington M, Siliciano RF, Siliciano JM, Deeks SG, Walker BD, Lichterfeld M, Yu XG. 2020. Distinct viral reservoirs in individuals with spontaneous control of HIV-1. Nature 585:261-267. [CrossRef]

- Rodari A, Darcis G, Van Lint CM. 2021. The Current Status of Latency Reversing Agents for HIV-1 Remission. Annu Rev Virol 8:491-514. [CrossRef]

- Parent M, Yung TM, Rancourt A, Ho EL, Vispe S, Suzuki-Matsuda F, Uehara A, Wada T, Handa H, Satoh MS. 2005. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a negative regulator of HIV-1 transcription through competitive binding to TAR RNA with Tat.positive transcription elongation factor b (p-TEFb) complex. J Biol Chem 280:448-57. [CrossRef]

- Vispe S, Yung TM, Ritchot J, Serizawa H, Satoh MS. 2000. A cellular defense pathway regulating transcription through poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in response to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:9886-91. [CrossRef]

- Yung TM, Satoh MS. 2001. Functional competition between poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase and its 24-kDa apoptotic fragment in DNA repair and transcription. J Biol Chem 276:11279-86. [CrossRef]

- Eustermann S, Videler H, Yang JC, Cole PT, Gruszka D, Veprintsev D, Neuhaus D. 2011. The DNA-binding domain of human PARP-1 interacts with DNA single-strand breaks as a monomer through its second zinc finger. J Mol Biol 407:149-70. [CrossRef]

- Henderson AJ, Zou X, Calame KL. 1995. C/EBP proteins activate transcription from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat in macrophages/monocytes. J Virol 69:5337-44. [CrossRef]

- Dahiya S, Liu Y, Nonnemacher MR, Dampier W, Wigdahl B. 2014. CCAAT enhancer binding protein and nuclear factor of activated T cells regulate HIV-1 LTR via a novel conserved downstream site in cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage. PLoS One 9:e88116. [CrossRef]

- Perkins ND. 2007. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:49-62. [CrossRef]

- Sen R, Smale ST. 2010. Selectivity of the NF-{kappa}B response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000257.

- Garcia-Rivera JA, Bueno MT, Morales E, Kugelman JR, Rodriguez DF, Llano M. 2010. Implication of serine residues 271, 273, and 275 in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cofactor activity of lens epithelium-derived growth factor/p75. J Virol 84:740-52. [CrossRef]

- Trinite B, Ohlson EC, Voznesensky I, Rana SP, Chan CN, Mahajan S, Alster J, Burke SA, Wodarz D, Levy DN. 2013. An HIV-1 replication pathway utilizing reverse transcription products that fail to integrate. J Virol 87:12701-20. [CrossRef]

- Bueno MT, Garcia-Rivera JA, Kugelman JR, Morales E, Rosas-Acosta G, Llano M. 2010. SUMOylation of the lens epithelium-derived growth factor/p75 attenuates its transcriptional activity on the heat shock protein 27 promoter. J Mol Biol 399:221-39.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).