1. Introduction

There search of complex networks has always been a focus of widespread attention. Complex networks can effectively describe and represent large-scale complex systems in the world, such as biological systems [

1,

2] , medical systems [

3], power systems [

4,

5], and social systems [

6,

7].In addition, identifying important nodes in complex networks has applications in various fields. In the field of biology, the identification of important nodes can help reveal key genes, proteins, or other biological molecules, thereby deepening the understanding of the key functions and regulatory mechanisms of biological systems [

8]. For the prevention of infectious disease spread, the identification of important nodes helps to identify and control key spreaders in the spread of infectious diseases, thereby effectively formulating intervention strategies and preventive measures[

9]. For the maintenance of power systems, the identification of important nodes helps to optimize the stability, reliability, and efficiency of power networks, as well as effectively managing energy distribution and supply strategies [

10]. For curbing the spread of rumors, the identification of important nodes helps to identify and control key spreaders in rumor dissemination, thereby effectively preventing and responding to the spread of rumors [

11].

There are many existing methods for identifying important nodes in complex networks. Traditional methods for identifying important nodes are based on local and global information of the network, such as degree centrality [

12]and k-shell centrality [

13]. the degree centrality method posits that the more neighbors a node has, the more important the node is. the k-shell centrality method, on the other hand, suggests that a node's position and hierarchical structure within the entire network significantly influence its importance, with nodes closer to the network core being considered more important. although traditional methods have achieved good results in some respects, they still have many shortcomings. in recent years, m. [

14] have proposed a method for identifying important nodes in complex networks based on the gravity model. this approach leverages the universal law of gravitation, treating a node's degree value as its 'mass' and the shortest path between nodes as the 'distance' between them, and calculates the force between nodes as an estimate of node importance. Compared to traditional methods, the gravity model-based approach can more accurately capture the complex relationships and interactive influences between nodes, resulting in more precise outcomes.

Y.D.[

15]proposed a gravity model method based on effective distance, which considers effective distance as the distance between nodes and the degree of nodes as their mass. They believe that effective distance can uncover the hidden dynamic structure and dynamic interaction information between nodes, which contains the way the network actually operates, and combining dynamic and static information to identify important nodes can improve the accuracy of the results.L.H.[

16] introduced a method known as the generalized gravity model, which takes the shortest distance between nodes as the distance and propagation capability as the mass. The propagation capability of a node is represented by the node's local clustering coefficient and degree. L.H. argue that if nodes have the same degree, the node with a higher local clustering coefficient, that is, the node with more edges connected to neighboring nodes, has a stronger ability to propagate information, thus the propagation capability of a node can more accurately measure the local information of the node.

In summary, previous research on methods for identifying key nodes has analyzed node interactions from various perspectives, thereby providing a more comprehensive assessment of node importance. However, these methods have not yet fully leveraged the multi-scale characteristics of nodes for in-depth analysis. Consequently, this study proposes a novel approach, which we term the local effective distance integration with gravity model (LEDGM).LEDGM is rooted in the recognition that nodes in complex networks possess intricate relationships that extend beyond their immediate connections. Our approach is anchored in the belief that a holistic analysis, which considers the multifaceted nature of nodes, is essential for accurately capturing their true influence within the network.By integrating various attributes such as local, global, positional, and clustering information, our model endeavors to paint a more nuanced picture of each node's role and potential impact. This comprehensive assessment allows for a more precise identification of key nodes that are pivotal to the network's structure and function. The LEDGM is designed to bridge the gap between traditional methods and the complex reality of network dynamics, providing a framework that is both sophisticated and adaptable to the nuances of different network topologies. Our main contributions are outlined as follows::

(1). We propose a novel approach called the local effective distance integrated gravity model. This model is specifically designed to offer a more comprehensive assessment of a node's spreading capability and significance. It incorporates several crucial pieces of information about the nodes, including their local and global characteristics, their positions within the network, and their clustering behavior.By taking all these factors into account, our model provides a more nuanced understanding of each node's role and influence within the network. This enables researchers and practitioners to identify important nodes with greater precision, which is essential for various applications such as targeted interventions, information dissemination strategies, and network resilience enhancement.

(2). We propose a method based on an effective influential node set. It can adaptively determine the number of nodes to consider according to the network topology, thus improving the algorithm's efficiency and accuracy effectively.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. We present the relevant research in

Section 2, including a series of foundational research and centrality measurement methods. The Improved effective distance fusion gravity model proposed in this paper is introduced in detail in

Section 3 . In

Section 4, we will demonstrate the effectiveness of this method through multiple experiments, analyze the experimental results, and summarize this paper in

Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

Given an undirected graph G=(V,E), where V represents the set of nodes and E represents the set of edges. The number of nodes in the graph is denoted by N, where N=|V|.The adjacency matrix of graph G is denoted as A = , where = 1 indicates that there is an edge between node i and node j, and =0 indicates that there is no edge between node i and node j. Additionally, represents the shortest distance between node i and node j.

2.1 Related research

2.1.1 Effective Distance (D)

Effective distance is a concept abstracted from probability, representing the true distance between two nodes compared to the shortest distance. If node i is directly connected to node j, the effective distance from i to j is given by:

where

is the probability of node i reaching node j,

is the element in the adjacency matrix of graph G, and

denotes the degree of node i. For nodes that are not directly connected, their effective distance can be obtained through transitivity. If there are multiple paths from node i to node j, the shortest path between the two nodes is taken as their effective distance.

2.1.2 Local Clustering Coefficient()

The local clustering coefficient is a measure of the degree to which nodes connected to a particular node are also connected to each other. It describes the density of connections between neighbors of a node, that is, the extent to which nodes in the local sub-graph centered on a node form closed triangles. A high local clustering coefficient indicates that the neighbors of a node are more likely to be connected to each other. The specific formula is as follows:

where

represents the degree of node i, and

represents the number of edges between neighbors of node i.

2.1.3 Truncation Radius (R)

The truncation radius is a concept in complex networks, usually referring to the average shortest path length from a node to other nodes in the network, considering only paths with lengths not greater than a certain truncation value R. It is used to describe the local connectivity characteristics between nodes in the network, especially playing an important role in large-scale networksDue to the extensive computational requirements involved in determining the network's truncation radius, Z discovered through extensive experiments that the algorithm performs optimally when R is set to half the diameter of the network.

2.1.4 Effective Influence Node Set()

In previous studies, when employing the gravitational model based on effective distance to calculate the centrality index of nodes, researchers typically considered all nodes in the network. However, this approach is not appropriate because the influence of a node on distant nodes is usually negligible, and such redundant calculations can lead to distorted results and reduced computational efficiency. Research by Z.[

17] has shown that using a truncated radius in the gravitational model to assess the importance of nodes can significantly reduce the time complexity of calculations and enhance the precision of experiments. Subsequent gravitational models proposed have largely adopted the concept of the truncated radius R.

Nevertheless, the calculation of effective distance is costly, and directly comparing the effective distance between nodes with the truncated radius is not practical. To address this issue, we introduce the concept of an effective influence node set. According to previous studies, the shortest distance can serve as a measure of the distance between nodes, while the effective distance can reveal hidden dynamic structures and dynamic interaction information between nodes, reflecting the actual operation of the network. Therefore, we define the nodes whose shortest distance to node i is less than R as the effective influence node set

of node i,the formula is as follows:

Here, N denotes the total number of nodes in the network, represents the shortest distance between nodes i and j, and R signifies the network's truncation radius. If the specified condition is met, node j is added to the set of effective influential nodes .

2.2 Traditional Methods

2.2.1 Degree Centrality(DC)

DC evaluates the significance of a node based on the comparison of its degree. The degree centrality for a node i can be expressed with the following formula:

Here, denotes the degree of node i (the number of edges connected to it), and N represents the total number of nodes in the network. Degree centrality measures the number of direct connections of a node, thereby inferring the node's influence on information dissemination or resource flow.

2.2.2 Betweenness Centrality(BC)

BC [

18] considers the node's ability to act as a bridge or intermediary in the network, measured by the number of shortest paths passing through the node, as follows:

where

represents the number of shortest paths from node j to node k, and

(i) is the number of those paths passing through node i. A high betweenness centrality of node i indicates that it plays a more critical role in the network's information transmission.

2.2.3 Closeness Centrality(CC)

CC [

19] measures the average shortest path length from a node to all other nodes. A node with high closeness centrality can access other nodes in the network more quickly, which also means it plays an important role in the network's structure and information flow. The formula is as follows:

where N represents the number of nodes in the network, and

is the shortest path distance from node i to node j.

2.3 Methods Based On The Gravity Model

2.3.1 Gravity Model(GM)

GM is defined by drawing an analogy with Newton's law of universal gravitation. It takes the node's degree value as the node's 'mass' and the shortest path between nodes as the 'distance' between them. The formula for calculating it is as follows:

where

represents the set of neighbors of node i within the truncation radius R. k(i) and k(j) represent the degree values of nodes i and j, respectively, and

is the shortest path distance from node i to node j.

2.3.2 Effective Distance Gravity Model(EDGM)

proposed by Y.D. considers effective distance as the distance between nodes. It regards the degree of nodes as their mass, and the formula is as follows:

where N represents the total number of nodes in the network,

represent the degrees of nodes i and j, respectively, and

represents the effective distance from node i to node j。

2.3.3 Generalized Gravity Model(GGM)

GGMconsiders using the degree of a node as its mass to be too simplistic. Instead, it takes the node's propagation capability as the node's mass, with the shortest distance as the distance between nodes. The formula is as follows:

where

represents the shortest distance between nodes, R is the truncation radius,

represents the propagation capability of node i.

is the local clustering coefficient of node i, and

is the degree of node i. When the parameter α is set to 0, the GGM model is equivalent to the G model.

3. Identification of Important Nodes Based on Local Effective Distance Integration with Gravity Model

In existing methods for identifying important nodes in complex networks, the comprehensive consideration of node attributes is still inadequate. Studies indicate that neglecting local or topological information when assessing node importance can affect the accuracy of the evaluation results. This paper proposes a novel approach that incorporates the propagation capacity and effective distance of nodes as key parameters within the gravity model framework, to thoroughly consider the local characteristics, global characteristics, positional characteristics, and clustering characteristics of nodes. However, for large-scale networks, calculating the effective distance between all node pairs is not only time-consuming but also impractical, as nodes typically exert minimal influence on those that are far away. Moreover, due to noise accumulation, the interaction strength between distant nodes is difficult to measure accurately. This study addresses these issues by effectively delineating the influence range of nodes, thereby enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of the method.

3.1 Algorithm

Step 1: Calculate the effective influence node set of nodes

In this step, we calculate and store the effective influence node set for all nodes in the network. Nodes that are within a shortest distance less than R from a node are included in the effective influence node set of that node.

Step 2: Calculated effective distance

The method for calculating the effective distance between node i and node j is detailed in Section II.A. Specifically, in this step, we compute and store the effective distances between all nodes in the network and the nodes within their effective influence set.

Step 3:Calculate the attraction between nodes

The attractiveness between nodes can be determined using the gravitational formula, where the propagation capability and effective distance of nodes are calculated. A node's propagation capability is derived from its degree, K-Shell value, and local clustering coefficient. Inspired by the Generalized Gravity Model model, we recognize that when nodes have the same degree, the closeness of a node to its surrounding nodes affects its propagation capability.

Building on this, it is evident that when two nodes have the same degree of closeness with their surrounding nodes, the node located at the core of the network is more important, indicating that a node's position within the network topology also affects its propagation capability. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

where

is the effective distance from node i to j, and

represents the propagation capability of node i, with the specific formula as follows:

where

is the local clustering coefficient of node i,

is the degree of node i,

is the maximum degree in the network,

is the K-Shell value of node i, and

is the maximum K-Shell value in the network.

Step 4: Calculate the importance of nodes

When calculating the importance of a node, the gravitational forces between the node and the nodes within its effective influence set should be summed. The specific formula is as follows:

where

is the effective influence node set of node i, and

is the importance of node i.

3.2 Example

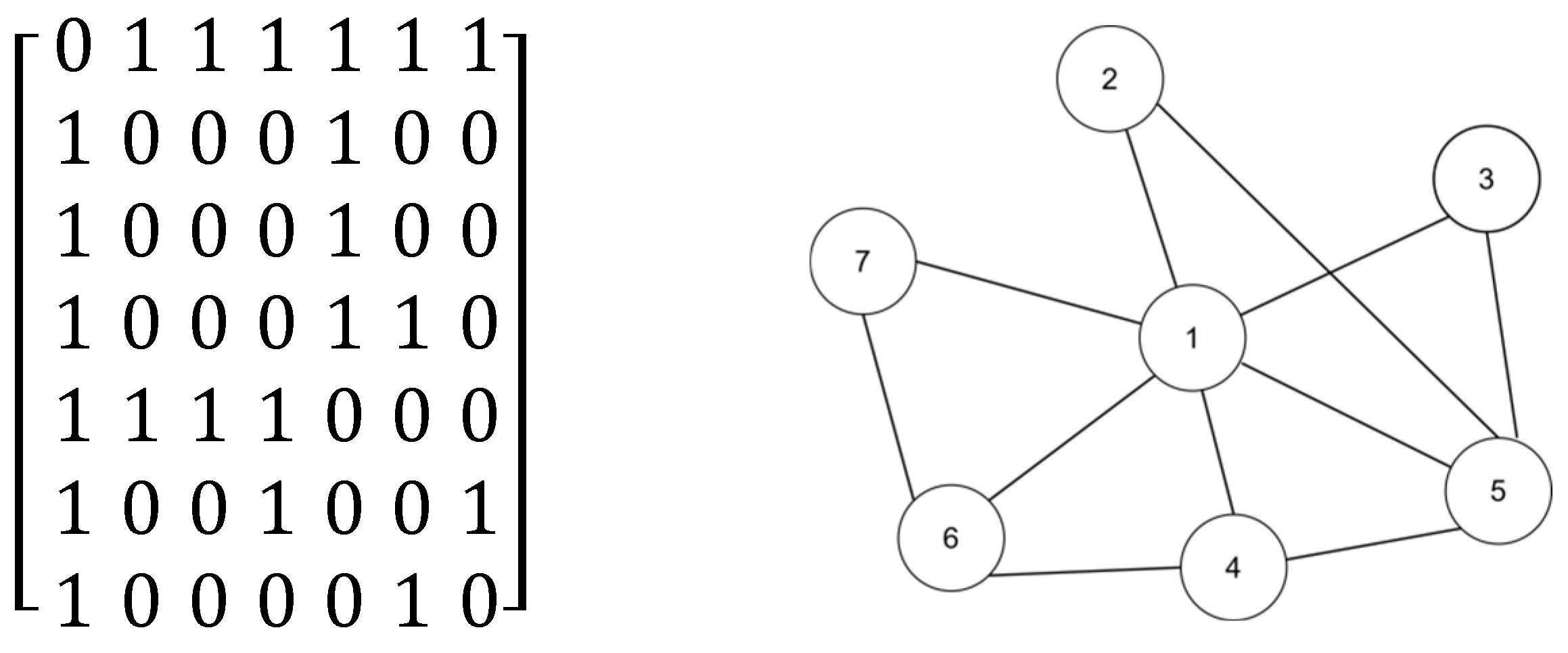

Figure 1 presents an example diagram that includes a simple network and its corresponding adjacency matrix. Initially, we explain the working principle of our algorithm by calculating the LEDGM centrality index for node 2, and then we demonstrate the effectiveness of the effective influence set calculation.

The following section outlines the steps for calculating the LEDGM :

Step 1: Obtain the effective influence node set of node 2

As shown in

Figure 1, the diameter of the network is 2, so its truncation radius is 1. By comparing whether the shortest distance with node 2 is less than the truncation radius, the effective influence node set of the node can be obtained

,

。

Step 2: Calculate the effective distance between node 2 and its effective influence node set

Using the formula in Definition 2.1.1, we can calculate the effective distance between node 2 and other nodes in its effective influence node set, with the specific calculation process as follows:

Step 3: Calculate the attraction between node 2 and its effective influence node set

The specific method for calculating the attraction between node 2 and node 1 is as follows:

Similarly, the attraction between node 2 and node 5 can be obtained.

Step 4: Calculate the importance of node 2

Using the formula in Step 4 of Section III.A for calculation, the specific calculation is as follows:

To demonstrate the efficacy of the effective influence set,

Table 1 presents the indices for each node in the network, while

Table 2 shows the indices for each node when the effective influence set is not considered. A straightforward calculation reveals that without the effective influence set, the number of computations required to determine the effective distances between all node pairs in the network is 42, which is equivalent to n*(n−1). However, with the effective influence set, the number of computations is reduced to 20. This reduction significantly lowers the time complexity of the algorithm. Additionally, by comparing the data in

Table 1 and

Table 2, it is evident that the nodes within the effective influence set play a predominant role in the calculation of node importance.

4. Experiments and Data

This chapter aims to validate the feasibility and superiority of our proposed method by conducting four different experiments on six real-world networks, comparing it with traditional centrality methods and other similar approaches. Specifically, in

Section 4.1, we detail the characteristics of these six real-world network datasets, including the number of nodes, the number of edges, the average degree of the network, and the network's propagation threshold. In

Section 4.2, we employ traditional methods (such as Degree Centrality (DC), Closeness Centrality (BC), Betweenness Centrality (CC), and K-shell (KS) methods) as well as other methods similar to ours (such as GM, EDGM, GGM, and our proposed LEDGM method) to rank the top 10 nodes in these six networks. In Section 4.3, we utilize the SI (Susceptible-Infected) model and, based on the ranking results from different methods, select the top ten nodes as initial infected nodes to verify and analyze the changes in the model's contagion capabilities under different initial node selections. Additionally, in

Section 4.4, we compare the time required for our method and the EDGM method to obtain node influence rankings on the same dataset. Finally, in Section IV.E, by comparing the ranking results of the SI model with other methods, we analyze the changes in Kendall's tau correlation coefficient under different propagation probabilities.

4.1 Datasets

In this paper, we utilize six datasets for our experiments, including Jazz [

20], NS [

21], Email [

22], EEC [

23], PB [

24], and USair [

25] . These encompass two communication networks (Email, EEC), a transportation network (USair), a social network (PB), and two collaboration networks (Jazz, NS). The email network describes the communication patterns among researchers via email; the EEC network represents the electronic communication network among members of European research institutions; the Jazz network illustrates the cooperation among jazz musicians; the NS network is a network of scientists collaborating and working together; the USair network is the transportation network of American air travel; and the PB network is a hyperlink network representing the relationships between American political blogs. Selecting these datasets from different domains ensures the comprehensiveness and generality of our experimental results.

Table 3 presents detailed information about the six networks, including the total number of network nodes N, the number of network edges E, the average shortest distance <d> between nodes, the average degree <k> of nodes, the network clustering coefficient C, and the network propagation threshold

.

4.2 Experiments 1: Top the Nodes

In this experiment, we conducted a comparative analysis of the similarity among the top ten nodes identified by eight different methods across six networks, aiming to reveal the similarities and differences between these methods. The eight methods include our proposed LEDGM method, traditional methods DC, BC, CC, KS, and similar methods GM, EDGM, and GGM. Since each method considers different node characteristics, there are differences in the ranking lists they generate. The number of recurring nodes can, to some extent, reflect the effectiveness of our method. It is important to note that due to significant differences in the characteristics considered by the KS decomposition method compared to others, we did not compare its ranking similarity with the LEDGM method.

For detailed ranking results, refer to

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7,

Table 8 and

Table 9. In the Email network, the CC and GGM methods identified the same top ten nodes as the LEDGM method. Other methods shared 7 to 8 nodes with the LEDGM method, a number lower than that of the CC and GGM methods. In the EEC network, all methods showed a high similarity with the nodes identified by the LEDGM method, with the CC and GGM methods sharing 9 nodes with the LEDGM method. In the Jazz network, the BC and GGM methods had the fewest common nodes with the LEDGM method, while other methods had between 7 and 8 common nodes. In the NS network, the BC and CC methods had the fewest common nodes with the LEDGM method, only 5, while the GGM method had slightly more, and other methods had between 7 and 8 common nodes. In the USair network, the DC method identified the same nodes as the LEDGM method, while the BC method had the lowest number of common nodes with the LEDGM method, 6, and other methods had between 8 and 9 nodes. In the PB network, the DC method identified the same nodes as the LEDGM method, and other methods all had 9 common nodes with the LEDGM method. Analyzing the tabular data, we found that the LEDGM method had a high number of consistent nodes with other methods across different networks, indicating its good adaptability and confirming the rationality of our proposed method. Furthermore, our proposed method performed similarly to other methods across different networks, suggesting that the LEDGM method can effectively integrate global and local characteristics as well as static and dynamic information.

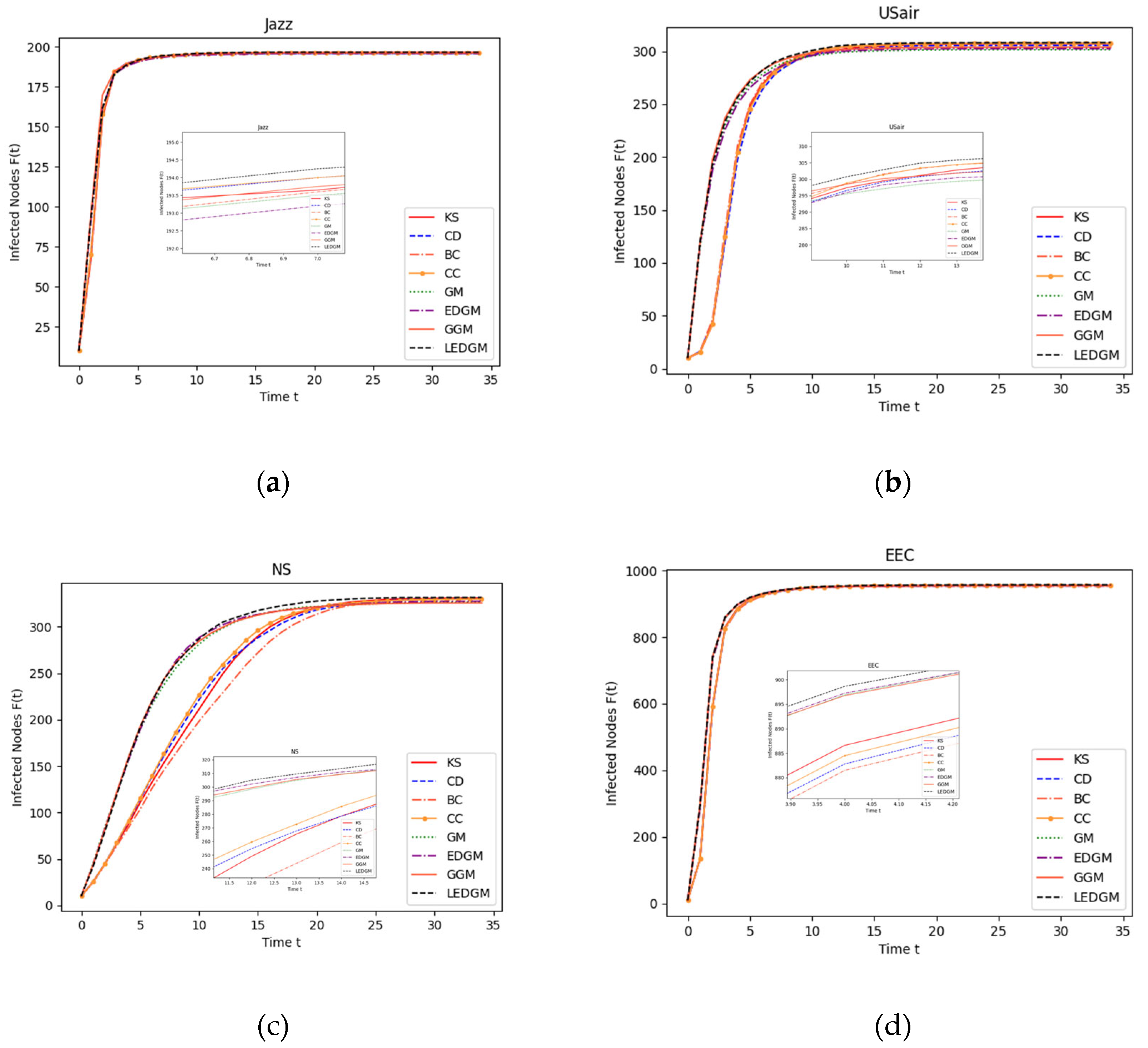

4.3 Experiments 2: SI Model

The SI model [

26] is a traditional epidemic model used to simulate the spread of infectious diseases in networks to assess the propagation capability of nodes within the network. In the SI model, nodes are divided into two states: (1) Susceptible (S); (2) Infected (I). The specific propagation process is as follows: Infected nodes I spread the disease to susceptible nodes S at a certain infection rate β, after which susceptible nodes S become infected nodes, and infected nodes I remain unchanged. Throughout this process, the total number of nodes N in the complex network remains constant (N = S + I). The faster the increase in the number of infected nodes, the more influential the source of infection is considered to be.

In this experiment, we selected the top ten nodes identified by various methods in

Section 4.2 as the initial infected nodes, with the remaining nodes in the network considered as susceptible nodes. These infected nodes infect surrounding susceptible nodes at an infection rate of β=0.2. To ensure the objectivity of the experimental results, each experiment was conducted independently 100 times, and the average outcomes are presented in

Figures 2 . We observed that the higher the importance of a node within the network, the faster the rate of increase in the number of infected individuals, and consequently, the greater the total number of infected individuals obtained at the end of the experiment.

As shown in

Figure 2, in the six networks, the LEDGM method's infection growth rate and maximum infected nodes are better than those of the other seven methods.

Figure 2(c) to 2(f) indicate that gravity - model - based methods outperform similarity - based ones in large networks, with LEDGM being more effective than the other three gravity - model - based methods. This is because LEDGM considers nodes' local, global, positional, and clustering information for a more comprehensive assessment of their spreading ability and importance.

Experiments on six real - world networks show that although LEDGM may not be the best in all networks, it has significant advantages in most, especially compared to GM, GGM, and EDGM. This highlights LEDGM's superiority and strong versatility across different network types.

4.4 Experiments 3: Validate The Role of The Effective Influential Node Set

In this experiment, we analyze the role of the effective influential node set. By comparing the time taken by two methods, we aim to show its superiority in reducing algorithm time complexity.

From an algorithmic perspective, the effective influential node set significantly reduces time complexity. Although effective distance better measures node interactions in complex networks, enhancing analysis efficiency and model predictability, its calculation requires assessing all possible paths between node pairs, resulting in high time complexity O. This makes methods using effective distance computationally expensive, especially for large - scale networks.

To tackle the issue, the LEDGM method introduces an effective influential node set. It uses a screening algorithm to filter out nodes that significantly impact the target node, reducing the number of node pairs for effective distance calculation. This screening algorithm has a time complexity of O, which greatly cuts the time cost of computing effective distances between network nodes.

In networks where node proximity isn't obvious, nodes have more "distant relatives" that are far - away and have negligible influence on the target node. The screening of the effective influential node set can further reduce the number of distance calculations, boosting algorithm efficiency.

Table 10 shows the specific experimental performance.

An experimental analysis of the role of effective influential node sets in reducing algorithmic time complexity.(The hardware used in this experiment was an Intel® Core™ 12th Gen i3-12100F processor with a clock speed of 3.30 GHz. The software environment was Python 3.12.3.)

Table 10 shows that in all six real - world networks, the method with the effective influential node set was more efficient than that without it. It reduced experimental time consumption by 57.91% in the best - performing network and by at least 13.28% in the worst - performing one.By analyzing the average shortest path length, network diameter, and global clustering coefficient, we found that the Email and USair networks have weak node connectivity and longer paths. This explains why the effective influential node set is more effective in these networks.

By filtering out nodes with significant impact on the target node, the effective influential node set reduced the number of node pairs for effective distance calculation. This lowered the algorithm's time complexity and made using effective distance feasible in large - scale networks. Thus, the LEDGM method achieved a significant improvement in algorithmic efficiency while maintaining high accuracy.

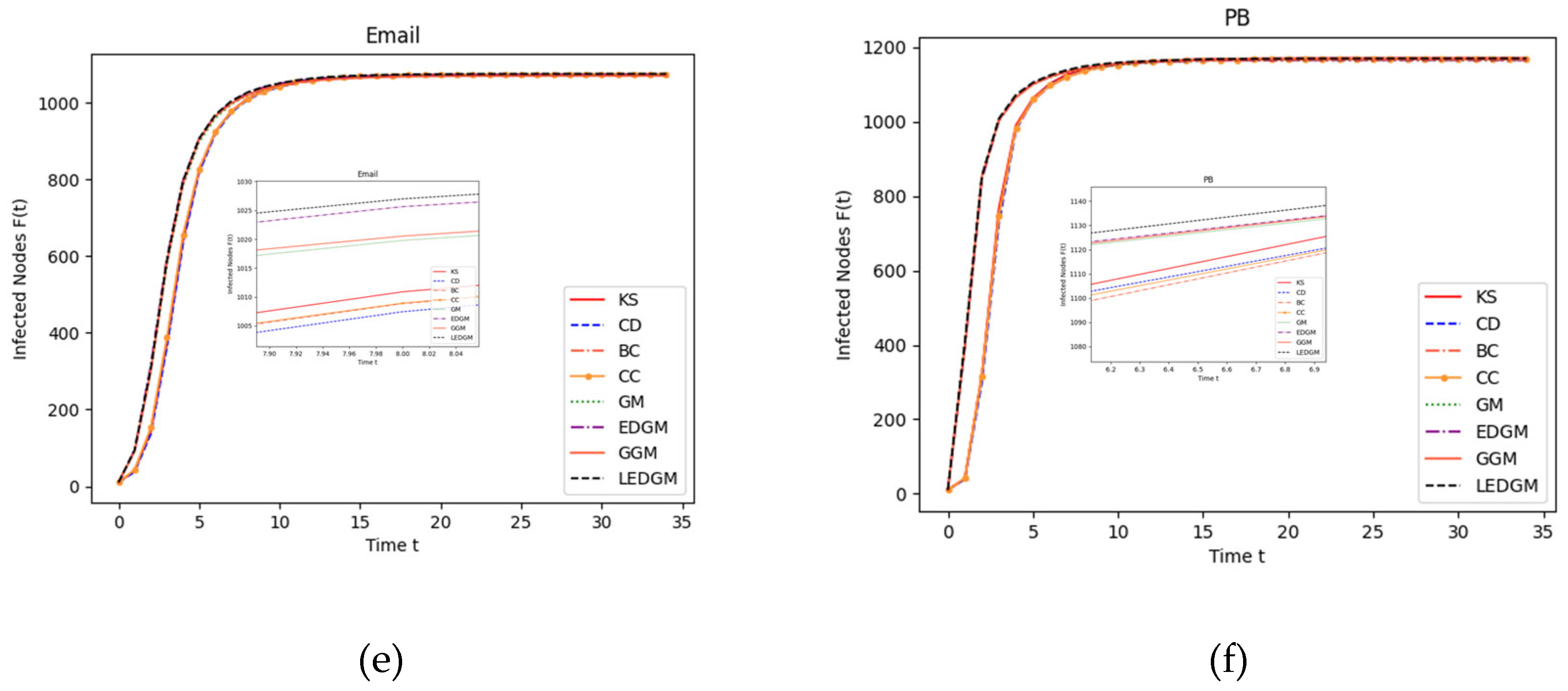

4.5 Experiments 4: Kendall's Coefficient

In this experiment, we used Kendall's coefficient[

27] to measure the correlation between the ranking results of different methods and the node ranking results obtained from the SI model, thereby proving the accuracy of the node importance ranking results between our proposed method and other related methods. Assume there are two sequences X and Y, each containing N nodes, where X = (

,...,

), Y = (

,...

). Then, a new sequence XY is constructed, where XY = ((

),(

),...,(

)), meaning the elements of XY are the one-to-one corresponding results between the elements of X and Y. In sequence XY, for any pair of elements (

) and (

), if

and

, or

and

, then this pair is considered concordant; if

and

, or

and

j, then this pair is considered discordant; if

, then this pair is considered neither concordant nor discordant. The expression for Kendall's coefficient tau is:

where the number of concordant pairs and discordant pairs are denoted by

and

, respectively. The value of τ ranges from -1 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating a higher positive correlation and values closer to -1 indicating a higher negative correlation.

In this experiment, we utilized the ranking sequences generated by the SI model as a benchmark to assess the accuracy of the ranking sequences produced by the new method proposed in Experiment 4.3. When generating the SI model's ranking sequences, each node in the network was selected once as the initial infected node in each simulation. To ensure the reliability of the simulation results, each simulation was independently executed 100 times, and the results were averaged to obtain a standard ranking of node influence. We employed the Kendall coefficient to measure the correlation between the standard ranking sequences of nodes simulated by the SI model and those generated by other methods, thereby assessing the accuracy of the methods. The methods compared include DC, BC, CC, GM, GGM, and EDGM. To ensure the objectivity and validity of the experiment, we adjusted the infection probability β in the SI model and conducted simulation experiments, repeating each simulation 100 times and averaging the results to evaluate the effectiveness of different comparison methods under varying infection probabilities. The average results of the experiments are shown in

Figure 3. A higher Kendall coefficient indicates a higher correlation with the sequences produced by the SI model, thereby demonstrating the superior performance of the method in terms of accuracy.

By analyzing the data presented in

Figure 3, we observed that the LEDGM method consistently ranked first across all six real-world networks. In the Jazz and PB networks, the performance of the EDGM method was close to that of the LEDGM method, yet slightly inferior. We attribute the emergence of these experimental results to the LEDGM method's ability to adapt to the network's topological structure and effectively integrate multidimensional information of the network, thereby accurately capturing the true influence of nodes within the network. Combining the experimental results from the six real-world networks, we conclude that the LEDGM method demonstrates significant superiority compared to other methods.

5. Conclusions

In order to identify Important nodes in complex networks more efficiently and accurately, we propose a method named LEDGM. This method integrates various attribute features of nodes, characterizing their propagation capabilities by synthesizing node attribute information, thereby effectively identifying influential nodes within the network. Furthermore, the LEDGM method enhances computational efficiency by employing an effective influence node set, reducing redundant calculations of effective distances between nodes. Through analysis in experiments based on the SI disease spread model across six real-world network datasets, we found that the LEDGM method shows great potential in areas such as information transmission, social networking, and road transportation. Compared to seven other methods, the nodes selected by the LEDGM method exhibit stronger propagation capabilities and stronger adaptability across different datasets, thereby proving its effectiveness and superiority. Concurrently, through analysis of time efficiency experiments, we found that the LEDGM method has a distinct advantage over the EDGM method in terms of time efficiency.

Although the LEDGM method has achieved significant effects in identifying important nodes and has also performed well in reducing time complexity, we must also recognize that if we can find the optimal balance between improving method accuracy and reducing time complexity, the capability and applicability of the LEDGM method will be further enhanced. By integrating multiple attributes of nodes, we recognize that the judicious and skillful use of multi-attribute node information can uncover deeper network node information and hidden topological structures. Therefore, exploring more advanced feature fusion methods will be a focal point of our future research.

Author Contributions

F.L. and S.Z conceived and designed the experiments; Y.H. and Z.L. performed the experiments; F.L. wrote the paper; S.Z. , K.S. and H.M. reviewed the paper and provided suggestions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 61661037, 62262043 and 72461026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The numerical calculations in this paper were done on the computing server of Information Engineering College of Nanchang Hangkong University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lei, X.; Yang, X.; Fujita, H. Random walk based method to identify essential proteins by integrating network topology and biological characteristics. Knowledge-Based Systems 2019, 167, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majhi, S.; Bera, B. K.; Ghosh, D.; Perc, M. Chimera states in neuronal networks: A review. Physics of Life Reviews 2019, 28, 100–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, M. W. L.; Rodrigues, J. J. P. C.; Korotaev, V.; Al-Muhtadi, J.; Kumar, N. A Comprehensive Review on Smart Decision Support Systems for Health Care. IEEE Systems Journal 2019, 13(3), 3536–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, Y.-P.; Zio, E. Risk Assessment of an Electrical Power System Considering the Influence of Traffic Congestion on a Hypothetical Scenario of Electrified Transportation System in New York State. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 22(1), 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; Liu, L.; Hill, D. J. Cascading risk assessment in power-communication interdependent networks. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2020, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R. C.; Figueiredo, D. R.; de, A. Rocha, A. A.; Ziviani, A. Efficient network seeding under variable node cost and limited budget for social networks R. Information Sciences 2020, 514, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P. G.; Quan, Y. N.; Miao, Q. G.; Chi, J. Identifying influential genes in protein–protein interaction networks. Information Sciences 2018, 454-455, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hong, Z.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Rodríguez-Patón, A.; Zou, Q.; Zeng, X. Computational methods for identifying the critical nodes in biological networks. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2020, 21(2), 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Tang, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Huang, C.; Xie, D.; Wang, T.; Zhao, C. Medical Cyber–Physical Systems: A Solution to Smart Health and the State of the Art. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems 2022, 9(5), 1359–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Shu, N.; Li, Z.; Li, F. Critical Nodes Identification for Power Grid Based on Electrical Topology and Power Flow Distribution. IEEE Systems Journal 2023, 17(3), 4874–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosni, A. I. E.; Li, K.; Ahmad, S. Analysis ofthe impact ofonline social networks addiction on the propagation ofrumors. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2020, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. E. J. The Structure and Function of Complex Networks. SIAM Review 2003, 45(2), 167–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsak, M.; Gallos, L. K.; Havlin, S.; Liljeros, F.; Muchnik, L.; Stanley, H. E.; Makse, H. A. Identification of influential spreaders in complex networks. Nature Physics 2010, 6(11), 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-l.; Ma, C.; Zhang, H.-F.; Wang, B.-H. Identifying influential spreaders in complex networks based on gravity formula. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2016, 451, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Cheong, K. H. Identifying influential nodes in complex networks: Effective distance gravity model. Information Sciences 2021, 577, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shang, Q.; Deng, Y. A generalized gravity model for influential spreaders identification in complex networks. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2021, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsahl, T. Triadic closure in two-mode networks: Redefining the global and local clustering coefficients. Social Networks 2013, 35(2), 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. E. J. A measure of betweenness centrality based on random walks. Social Networks 2005, 27(1), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavelas, A., Laurent Beauguitte, Julie Fen-Chon. Communication patterns in task-oriented groups. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1950.

- DANON, P. M. G. a. L. COMMUNITY STRUCTURE IN JAZZ. cond-mat 2003.

- Ahmed, R. A. R. a. N. K. The Network Data Repository with Interactive Graph Analytics and Visualization. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2015.

- R. Guimer`a, 2 L. Danon,3, 4 A. D´ıaz-Guilera,3, 1 F. Giralt,1 and A. Arenas4. Self-similar community structure in organisations. Social Enterprise Journal 2002.

- Yin, H.; Benson, A. R.; Leskovec, J.; Gleich, D. F. Local Higher-Order Graph Clustering. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2017.

- Glance, L. A. A. The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog. Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on Link discovery 2004.

- Vittoria Colizza, R. P.-S., Alessandro Vespignani. Reaction-diffusion processes and meta-population models in heterogeneous networks. Nature Physics 2007.

- W. O. Kermack, A. G. M. “A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 1927.

- Kendall, M. G. A NEW MEASURE OF RANK CORRELATION. Biometrika 1938. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).