Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

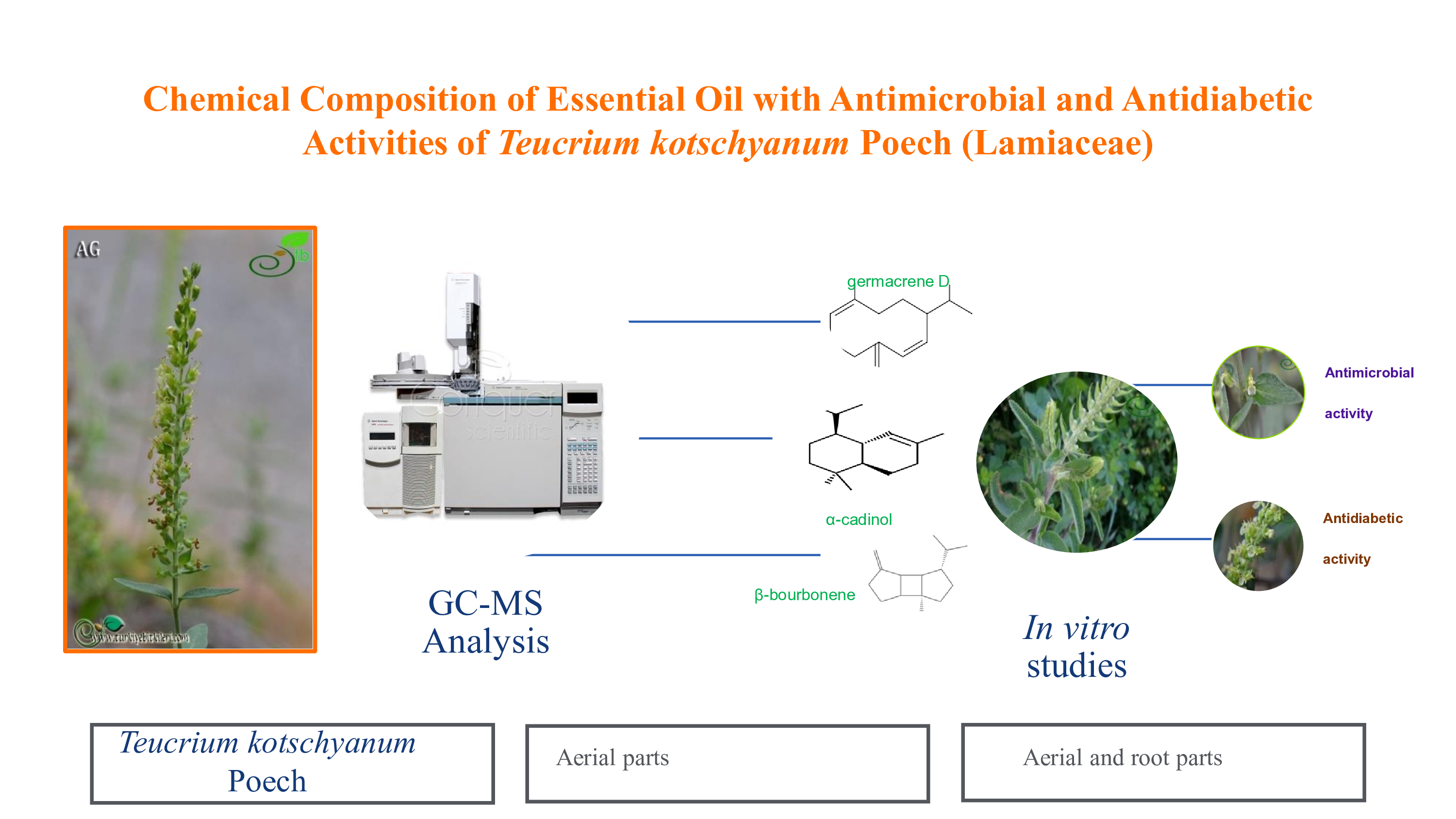

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity

2.3. α-Glucosidase Inhibition Activity

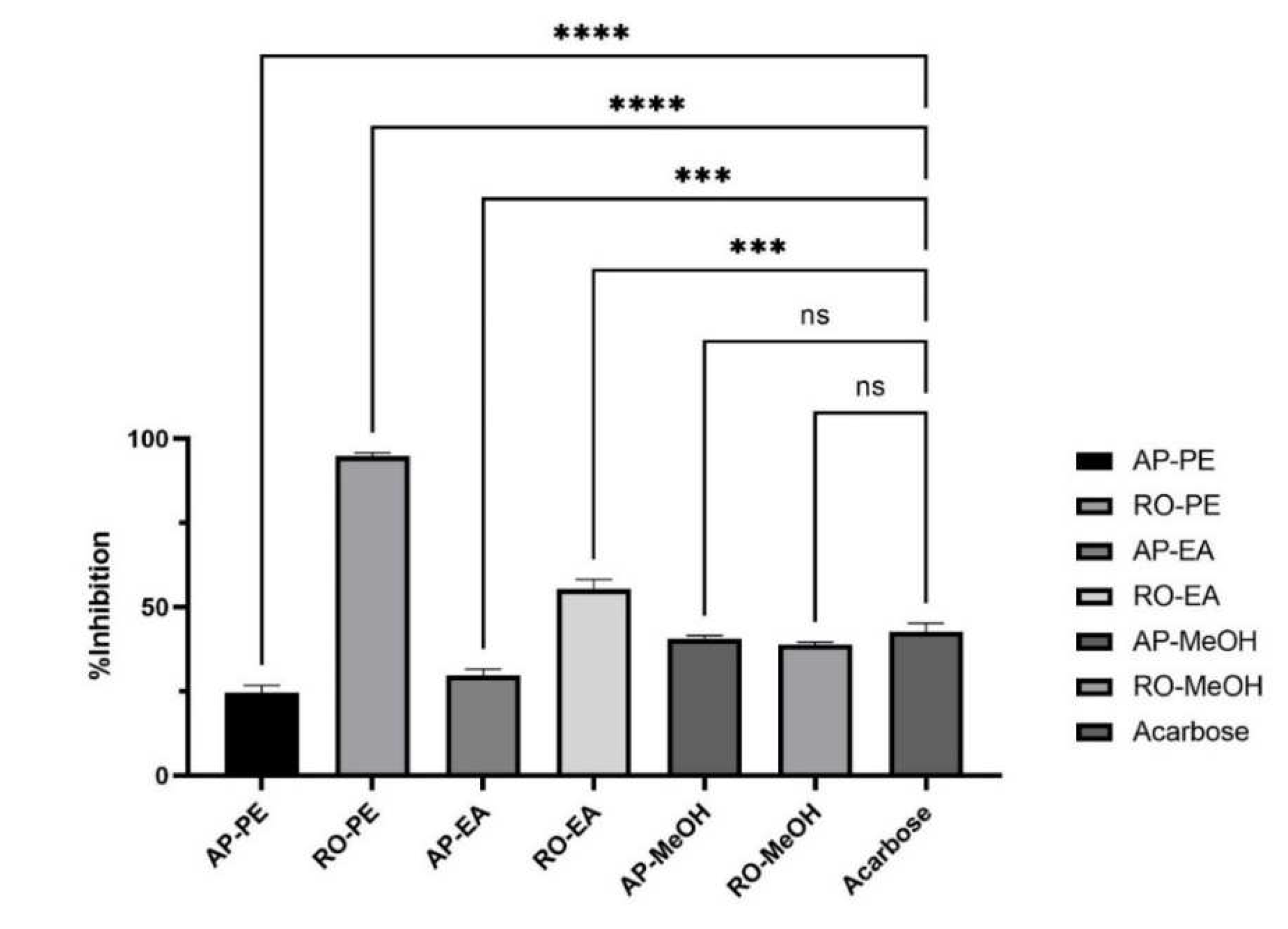

2.3.1. % Inhibition of Teucrium Kotschyanum Extracts

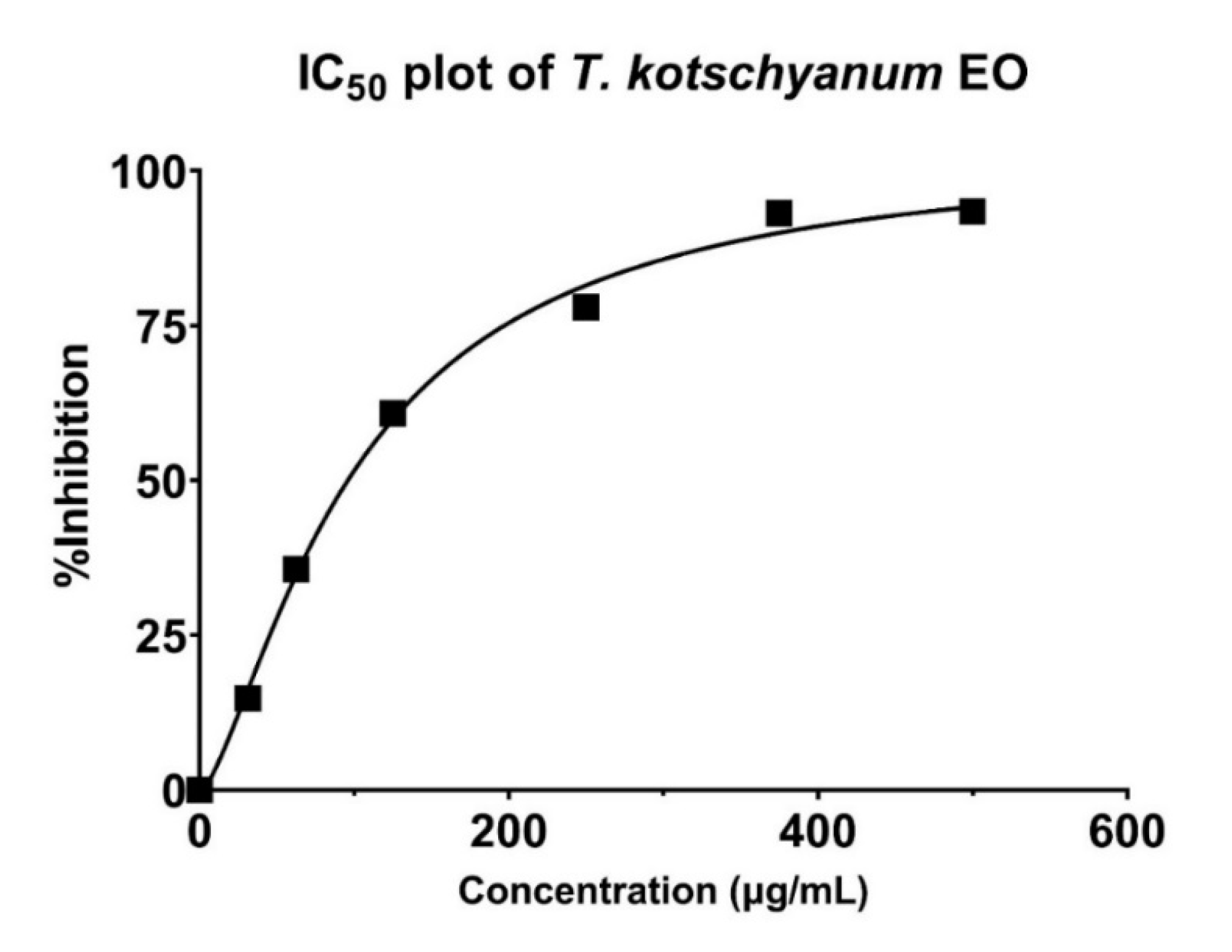

2.3.2. IC50 Value of Teucrium Kotschyanum Essential Oil

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Isolation of Essential Oil (EO)

Preparation of Extracts

Analysis of Essential Oil

Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Gas Chromatography Analysis

Antimicrobial Activity

α-Glucosidase inhibition Activity

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guiche, R. E.; Tahrouch, S.; Amri, O.; El Mehrach, K.; Hatimie, A. Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of 30 Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Located in the South of Morocco. Int. J. New Technol. Res. 2015, 1, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Govaerts, R. World Checklist Seed Plants 3; Continental Publishing: Deurne, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Duman, H. Teucrium L. In Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands; Güner, A., Özhatay, N., Ekim, T., Başer, K. H. C., Eds.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dönmez, A. A. Teucrium chasmophyticum Rech. f. (Lamiaceae): A New Record for the Flora of Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 2006, 30, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Parolly, G.; Eren, Ö. Contributions to the Flora of Turkey, 2. Wildenowia 2007, 37, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, A. A.; Mutlu, B.; Özçelik, A. D. Teucrium melissoides Boiss. & Hausskn. ex Boiss. (Lamiaceae): A New Record for Flora of Turkey. Hacettepe J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 38, 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dinç, M.; Doğu, S.; Bağcı, Y. Taxonomic Reinstatement of Teucrium andrusi from T. paederotoides Based on Morphological and Anatomical Evidences. Nord. J. Bot. 2011, 29, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinç, M.; Doğu, S.; Doğru Koca, A.; Kaya, B. Anatomical and Nutlet Differentiation Between Teucrium montanum and T. polium from Turkey. Biologia 2011, 66, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirmenci, T. Teucrium L. In Türkiye Bitkileri Listesi (Damarlı Bitkiler); Güner, A., Aslan, S., Ekim, T., Vural, M., Babaç, M. T., Eds.; Nezahat Gökyiğit Botanik Bahçesi ve Flora Araştırmaları Derneği Yayını: Istanbul, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, T.; Dirmenci, T.; Coşkun, F.; Akçiçek, E.; Güner, A. A New Species of Teucrium sect. Scordium (Lamiaceae) from SE of Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 2015, 39, 310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Vural, M.; Duman, H.; Dirmenci, T.; Özcan, T. A New Species of Teucrium sect. Stachyobotrys (Lamiaceae) from the South of Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 2015, 39, 318–324. [Google Scholar]

- Vukovic, N.; Sukdolak, S.; Solujic, S.; Mihailovic, V.; Mladenovic, M.; Stojanovic, J.; Stankovic, M. S. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Teucrium arduini Essential Oil and Cirsimarin from Montenegro. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, N. U.; Al-Sahai, J. M. S.; Hussain, H.; Khan, A. L.; Gilani, S. A.; Abbas, G.; Hussain, J.; Sabahi, J. N.; Al-Harrasi, A. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Investigation of Teucrium muscatense. Int. J. Phytomed. 2016, 8, 567–579. [Google Scholar]

- Menichini, F.; Conforti, F.; Rigano, D.; Formisano, C.; Piozzi, F.; Senatore, F. Phytochemical Composition, Anti-inflammatory and Antitumour Activities of Four Teucrium Essential Oils from Greece. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomaria, B.; Arnold, N.; Valentini, G. Essential Oil of Teucrium flavum subsp. hellenicum from Greece. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1998, 10, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünsal, Ç.; Vural, H.; Sariyar, G.; Özbek, B.; Ötük, G. Traditional Medicine in Bilecik Province (Turkey) and Antimicrobial Activities of Selected Species. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 7, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sargın, S. A. Ethnobotanical Survey of Medicinal Plants in Bozyazı District of Mersin, Turkey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piozzi, F.; Riello, A.; Mazzini, F.; Senatore, F. Essential Oils of Teucrium Species from the Mediterranean Area. Flavour Fragr. J. 2003, 18, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ulubelen, A.; Topçu, G.; Sönmez, U. Chemical and Biological Evaluation of Genus Teucrium. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2000, 23, 591–648. [Google Scholar]

- Ekim, T. Teucrium L. In Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands; Davis, P. H., Ed.; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, N. Contribution à la Connaissance Ethnobotanique et Médicinale de la Flore de Chypre. Université René Descartes: Paris, 1985; pp 1203–1210.

- Simoes, F.; Rodríguez, B.; Bruno, M.; Piozzi, F.; Savona, G.; Arnold, N. A. Neo-clerodane Diterpenoids from Teucrium kotschyanum. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 2763–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, N.; Bellomaria, B.; Valentini, G.; Rafaiani, S. M. Comparative Study on Essential Oil of Some Teucrium Species from Cyprus. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1991, 35, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljević, D.; Stanković, M. Application of Teucrium Species: Current Challenges and Further Perspectives. In Teucrium Species: Biology and Applications; 2020; pp 413–432.

- Esmaeili, M. A.; Yazdanparast, R. Hypoglycaemic Effect of Teucrium polium: Studies with Rat Pancreatic Islets. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 95, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidi, A. R.; Dashti, R. M.; Bagheri, S. M. The Effect of Teucrium polium Boiled Extract in Diabetic Rats. Iranian J. Diabetes Obesity 2010, 2, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dastjerdi, Z. M.; Namjoyan, F.; Azemi, M. E. Alpha Amylase Inhibition Activity of Some Plant Extracts of Teucrium Species. Eur. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Asghari, A. A.; Mokhtari-Zaer, A.; Niazmand, S.; McEntee, K.; Mahmoudabady, M. Anti-diabetic Properties and Bioactive Compounds of Teucrium polium L. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2020, 10, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N. A. A.; Wurster, M.; Arnold, N.; Lindequist, U.; Wessjohan, L. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil of Teucrium yemense Deflers. Records Nat. Prod. 2008, 2, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Saracoglu, V.; Arfan, M.; Shabir, A.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.; Skaltsa, H. Composition and Antioxidant Activity of the Essential Oil of Teucrium royleanum Wall. ex Benth Growing in Pakistan. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V.; Caputo, L.; Fratianni, F.; Nazzaro, F. Essential Oils Diversity of Teucrium Species. In Teucrium Species: Biology and Applications; Stanković, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Candela, R. G.; Roselli, S.; Bruno, M.; Fontana, G. A Review of the Phytochemistry, Traditional Uses and Biological Activities of the Essential Oils of Genus Teucrium. Planta Med. 2020, 87, 432–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bağcı, E.; Yazgın, A.; Hayta, S.; Çakılcıoğlu, U. Composition of the Essential Oil of Teucrium chamaedrys L. (Lamiaceae) from Turkey. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010, 4, 2588–2590. [Google Scholar]

- Küçük, M.; Güleç, C.; Yaşar, A.; Üçüncü, O.; Yaylı, N.; Coşkunçelebi, K.; Yaylı, N. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activities of the Essential Oils of Teucrium chamaedrys subsp. chamaedrys, T. orientale var. puberulens, and T. chamaedrys subsp. lydium. Pharm. Biol. 2006, 44, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, A.; Demirci, B.; Başer, K. H. C. Compositions of Essential Oils and Trichomes of Teucrium chamaedrys L. subsp. trapezunticum Rech. fil. and subsp. syspirense (C. Koch) Rech. fil. Chem. Biodivers. 2009, 6, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, A.; Demirci, B.; Dinç, M.; Doğu, S.; Başer, K. H. C. Compositions of the Essential Oils of Teucrium cavernarum and Teucrium paederotoides. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2013, 16, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başer, K. H. C.; Demirci, B.; Duman, H.; Aytaç, Z. Composition of the Essential Oil of Teucrium antitauricum T. Ekim. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1999, 11, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başer, K. H. C.; Demirçakmak, B.; Duman, H. Composition of the Essential Oils of Three Teucrium Species from Turkey. J. Essent. Oil Res. 1997, 9, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayta, S.; Yazgın, A.; Bağcı, E. Constituents of the Volatile Oils of Two Teucrium Species from Turkey. Bitlis Eren Univ. J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğu, S.; Dinç, M.; Kaya, A.; Demirci, B. Taxonomic Status of the Subspecies of Teucrium lamiifolium in Turkey: Reevaluation Based on Macro- and Micro-Morphology, Anatomy and Chemistry. Nord. J. Bot. 2013, 31, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, T.; Özer, H.; Öztürk, E.; Çakır, A.; Kandemir, A.; Demir, Y. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oil of Teucrium multicaule Montbret et Aucher ex Bentham from Turkey. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2010, 22, 443–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukbay, F. Z.; Yildiz, B.; Kuyumcu, E.; Gunal, S. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activities of the Essential Oils of Teucrium orientale var. orientale and Teucrium orientale var. puberulens. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2011, 47, 833–836. [Google Scholar]

- Bağcı, E.; Hayta, S.; Yazgın, A.; Doğan, G. Composition of the Essential Oil of Teucrium parviflorum L. (Lamiaceae) from Turkey. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 3457–3460. [Google Scholar]

- Bezic, N.; Vuko, E.; Dunkic, V.; Ruscic, M.; Blazevic, I.; Burcul, F. Antiphytoviral Activity of Sesquiterpene-Rich Essential Oils from Four Croatian Teucrium Species. Molecules 2011, 16, 8119–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morteza-Semnani, K.; Saeedi, M.; Akbarzadeh, M. Essential Oil Composition of Teucrium scordium L. Acta Pharm. 2007, 57, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muselli, A.; Desjobert, J. M.; Paolini, J.; Bernardini, A. F.; Costa, J.; Rosa, A.; Dessi, M. A. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oils of Teucrium chamaedrys L. from Corsica and Sardinia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2009, 21, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzani, S.; Muselli, A.; Desjobert, J. M.; Bernardini, A. F.; Tomi, F.; Casanova, J. Chemical Composition of Essential Oil of Teucrium polium subsp. capitatum (L.) from Corsica. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleiro, C.; Salgueiro, L. R.; Antunes, T.; Sevinate-Pinto, I.; Barroso, J. G. Composition of the Essential Oil and Micromorphology of Trichomes of Teucrium salviastrum, an Endemic Species from Portugal. Flavour Fragr. J. 2002, 17, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachicha, S. F.; Skanji, T.; Barrek, S.; Zarrouk, H.; Ghrabi, Z. G. Chemical Composition of Teucrium alopecurus Essential Oil from Tunisia. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2007, 19, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoy, E.; Ozkan, E. E.; Karahan, S.; Şahin, H.; Cinar, E.; Canturk, Y. Y.; Boga, M. Phytochemical Analysis of Essential Oils and the Extracts of an Ethnomedicinal Plant, Teucrium multicaule Collected from Two Different Locations with Focus on Their Important Biological Activities. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 153, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, M. S.; Stefanović, O.; Čomić, L.; Topuzović, M.; Radojević, I.; Solujić, S. Antimicrobial Activity, Total Phenolic Content and Flavonoid Concentrations of Teucrium Species. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2012, 7, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiters, A. K.; Tilney, P. M.; Van Vuuren, S. F.; Viljoen, A. M.; Kamatou, G. P.; Van Wyk, B. E. The Anatomy, Ethnobotany, Antimicrobial Activity and Essential Oil Composition of Southern African Species of Teucrium (Lamiaceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 102, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, D.; Müller, I.; Dunkić, V.; Vitali, D.; Stabentheiner, E.; Oberländer, A.; Kosalec, I. Chemical Traits and Antimicrobial Activity of Endemic Teucrium arduini L. from Mt Biokovo (Croatia). Open Life Sci. 2012, 7, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovic, N.; Sukdolak, S.; Solujić, S.; Mihailovic, V.; Mladenović, M.; Stojanovic, J.; Stankovic, M. Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Teucrium arduini Essential Oil and Cirsimarin from Montenegro. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Formisano, C.; Napolitano, F.; Rigano, D.; Arnold, N. A.; Piozzi, F.; Senatore, F. Essential Oil Composition of Teucrium divaricatum Sieb. ssp. villosum (Celak.) Rech. fil. Growing Wild in Lebanon. J. Med. Food. 2010, 13, 1281–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Vukovic, N.; Milosevic, T.; Sukdolak, S.; Solujic, S. Antimicrobial Activities of Essential Oil and Methanol Extract of Teucrium montanum. Evid-Based Complementary Altern Med. 2007, 4, 368170–368173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertout-Mouri, N.; Latrèche, A.; Mehdadi, Z.; Toumi-Benali, F.; Khaled, M. B. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of the Essential Oil of Teucrium polium of Tessala Mount (Western Algeria). Phytothérapie 2017, 15, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmekki, N.; Bendimerad, N.; Bekhechi, C.; Fernandez, X. Chemical Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of Teucrium polium L. Essential Oil from Western Algeria. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 897–902. [Google Scholar]

- Raei, F.; Ashoori, N.; Eftekhar, F.; Yousefzadi, M. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Teucrium polium Essential Oil Against Urinary Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2014, 26, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Atki, Y.; Aouam, I.; El Kamari, F.; Taroq, A.; Lyoussi, B.; Oumokhtar, B.; Abdellaoui, A. Phytochemistry, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Two Moroccan Teucrium polium L. Subspecies: Preventive Approach Against Nosocomial Infections. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 3866–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Othman, M.; Bel Hadj Salah-Fatnassi, K.; Ncibi, S.; Elaissi, A.; Zourgui, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil and Aqueous and Ethanol Extracts of Teucrium polium L. subsp. gabesianum (L.H.) from Tunisia. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukia, H.; Mahfoud, H. M.; Didi, O. E. H. M. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of the Essential Oil from Teucrium polium geyrii (Labiatae). J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 1506–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Bel Hadj Salah, K.; Mahjoub, M. A.; Chaumont, J. P.; Michel, L.; Millet-Clerc, J.; Chraeif, I.; Aouni, M. Chemical Composition and in vitro Antifungal and Antioxidant Activity of the Essential Oil and Methanolic Extract of Teucrium sauvagei Le Houerou. Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 20, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, A. A.; Mokhtari-Zaer, A.; Niazmand, S.; McEntee, K.; Mahmoudabady, M. Anti-Diabetic Properties and Bioactive Compounds of Teucrium polium L. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2020, 10, 433. [Google Scholar]

- Dastjerdi, Z. M.; Namjoyan, F.; Azemi, M. E. Alpha Amylase Inhibition Activity of Some Plant Extracts of Teucrium Species. Eur. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bassalat, N.; Tas, S.; Jaradat, N. Teucrium leucocladum: An Effective Tool for the Treatment of Hyperglycemia, Hyperlipidemia, and Oxidative Stress in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabet, Z.; Roghani, M.; Najafi, M.; Maghsoudi, Z. Antidiabetic Effect of Teucrium polium Aqueous Extract in Multiple Low-Dose Streptozotocin-Induced Model of Type 1 Diabetes in Rat. J. Basic Clin. Pathophysiol. 2013, 1, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi, T. S.; Hussain, I.; Ali, L.; Mabood, F.; Khan, A. L.; Shujah, S.; Halim, S. A. New Gorgonane Sesquiterpenoid from Teucrium mascatense Boiss, as α-Glucosidase Inhibitor. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 124, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majouli, K.; Hlila, M. B.; Hamdi, A.; Flamini, G.; Jannet, H. B.; Kenani, A. Antioxidant Activity and α-Glucosidase Inhibition by Essential Oils from Hertia cheirifolia (L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 82, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aba, P. E.; Asuzu, I. U. Mechanisms of Actions of Some Bioactive Anti-Diabetic Principles from Phytochemicals of Medicinal Plants: A Review. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour. 2018, 9, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Adefegha, S. A.; Olasehinde, T. A.; Oboh, G. Essential Oil Composition, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Antihypertensive Properties of Two Afromomum Species. J. Oleo Sci. 2017, 66, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer, M.; Rashid, M. N.; Mushtaq, M. N. H.; Malik, S. A.; Ghumman, M.; Numan, A. Q.; Khan, M. O.; Omer; Tahir, H. M. Pharmacological Evaluation of Antidiabetic Effect of Ethyl Acetate Extract of Teucrium stocksianum Boiss in Alloxan-Induced Diabetic Rabbits. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2013, 23, 436–439. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, S. E.; Shahriari, A.; Ahangarpour, A.; Vatanpour, H.; Jolodar, A. Effects of Teucrium polium Ethyl Acetate Extract on Serum, Liver and Muscle Triglyceride Content of Sucrose-Induced Insulin Resistance in Rat. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 11, 347. [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty, F. W.; Stauffer, D. B.; Stenhagen, E.; Heller, S. R. The Wiley/NBS Registry of Mass Spectral Data; 1989.

- Hochmuth, D. H. MassFinder 4.0; Hochmuth Scientific Consulting, Hamburg, Germany, 2008.

- CLSI (NCCLS) M7-A7. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, Seventh Edition, 2006.

- CLSI (NCCLS) M27-A2. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard, Second Edition, 2002.

- Bothon, F. T. D.; Debiton, E.; Avlessi, F.; Forestier, C.; Teulade, J. C.; Sohounhloue, D. K. In Vitro Biological Effects of Two Anti-Diabetic Medicinal Plants Used in Benin as Folk Medicine. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | RRI | % | IM |

| β-Pinene | 1118 | 0.4 | tR, MS |

| Sabinene | 1132 | 0.5 | tR, MS |

| Myrcene | 1174 | 0.1 | tR, MS |

| Limonene | 1203 | 1.2 | tR, MS |

| γ-Terpinene | 1255 | 0.2 | tR, MS |

| p-Cymene | 1280 | 0.3 | tR, MS |

| Terpinolene | 1290 | 0.2 | tR, MS |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 1452 | 1.0 | MS |

| α-Cubebene | 1466 | 0.1 | MS |

| α-Copaene | 1497 | 1.2 | MS |

| α-Bourbonene | 1528 | 0.5 | MS |

| β-Bourbonene | 1535 | 6.6 | MS |

| Linalool | 1553 | 2.8 | tR, MS |

| β-Ylangene | 1589 | 0.1 | MS |

| β-Copaene | 1597 | 0.2 | MS |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1611 | 0.9 | tR, MS |

| β-Caryophyllene | 1612 | 2.0 | tR, MS |

| Alloaromadendrene | 1661 | 3.0 | MS |

| epi-Zonarene | 1677 | 0.1 | MS |

| α-Humulene | 1687 | 2.2 | tR, MS |

| γ-Muurolene | 1704 | 1.2 | MS |

| α-Terpineol | 1706 | 1.1 | tR, MS |

| Bicyclosesquiphellandrene | 1722 | 1.3 | MS |

| Germacrene D | 1726 | 20.0 | MS |

| α-Muurolene | 1740 | 2.3 | MS |

| δ-Cadinene | 1773 | 5.9 | MS |

| γ-Cadinene | 1776 | 3.7 | MS |

| Methyl salicylate | 1798 | 0.3 | tR, MS |

| α-Cadinene | 1807 | 0.4 | MS |

| (E)-β-Damascenone | 1838 | 0.6 | MS |

| Calamenene | 1849 | 0.7 | MS |

| epi-Cubebol | 1900 | 0.4 | MS |

| α-Calacorene | 1941 | 0.1 | MS |

| Cubebol | 1957 | 0.7 | MS |

| 1-endo-Bourbonanol | 1968 | 0.1 | MS |

| γ-Calacorene | 1984 | 0.1 | MS |

| Caryophyllene oxide | 2008 | 0.8 | tR, MS |

| Salvial-4(14)-en-1-one | 2037 | 0.8 | MS |

| (E)-Nerolidol | 2050 | 0.2 | MS |

| Humulene epoxide-II | 2071 | 0.9 | MS |

| Cubenol | 2080 | 0.6 | MS |

| 1-epi-Cubenol | 2088 | 0.7 | MS |

| Viridiflorol | 2104 | 2.7 | MS |

| Salviadienol | 2130 | 0.7 | MS |

| Hexahydrofarnesyl acetone | 2131 | 0.9 | MS |

| Spathulenol | 2144 | 0.2 | MS |

| T-Cadinol | 2187 | 2.5 | MS |

| T-Muurolol | 2209 | 2.8 | MS |

| δ-Cadinol (=Torreyol) | 2219 | 1.0 | MS |

| α-Cadinol | 2255 | 6.9 | MS |

| Dodecanoic acid | 2503 | 1.3 | tR, MS |

| Manool | 2679 | 4.1 | MS |

| Hexadecanoic acid | 2931 | 6.6 | tR, MS |

| Total | 96.2 |

| Microorganisms | ||||||||||||

| Gram (+) bacteria |

Gram (-) bacteria | Fungi | ||||||||||

| EO / Reference standard | Sa | Se | Bc | Bs | Pa | St | Ca | Cg | Ck | Cp | Ct | Cu |

| Essential oil | 500 | 2000 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | 2000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 500 | 1000 | 125 |

| Ampicillin-Na | 16 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 0.5 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chloramphenicol | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 64 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Amphotericin | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| Ketoconazole | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| Sample | Inhibition% of α-glucosidase |

|---|---|

| AP-PE | 24.63 ± 2.12a |

| RO-PE | 94.79 ± 1.10b |

| AP-EA | 29.74 ± 1.90a |

| RO-EA | 55.49 ± 2.83c |

| AP-MeOH | 40.54 ± 0.96d |

| RO-MeOH | 38.97 ± 0.67d |

| Acarbose | 42.8 ± 2.50d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).