2.1. First-Order Analysis of the Levinson Beam

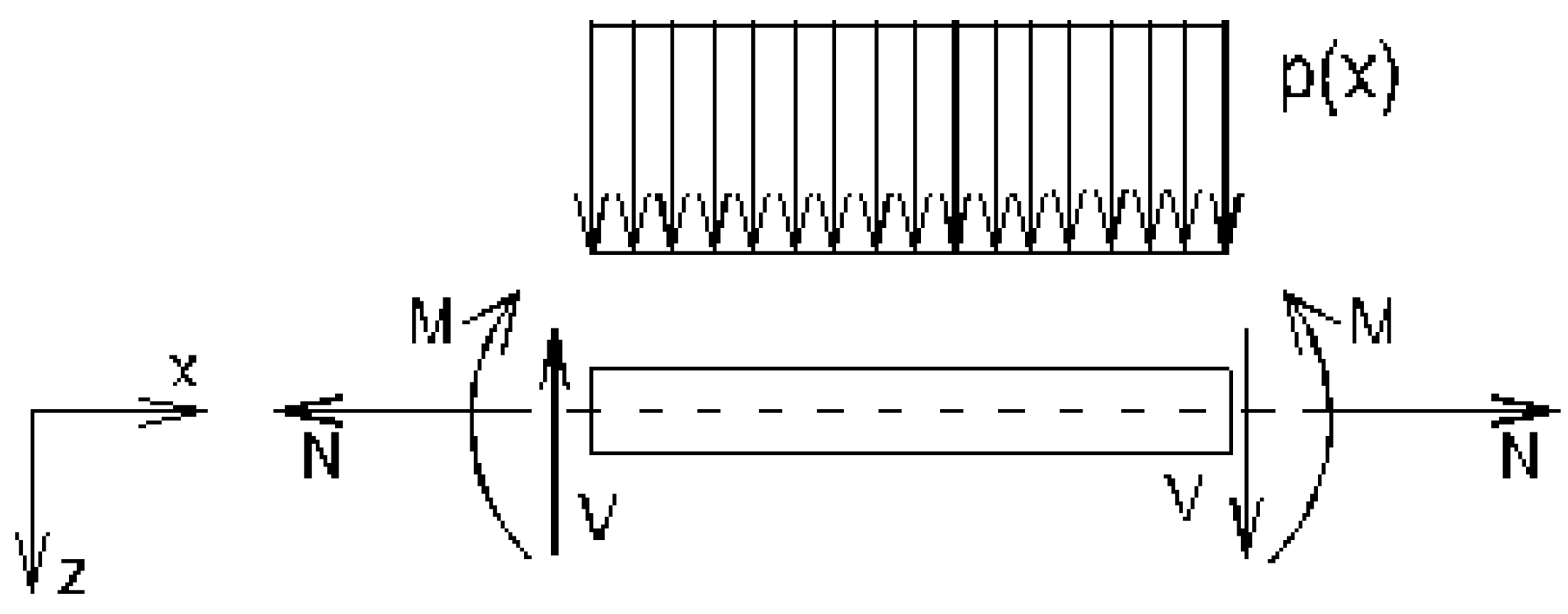

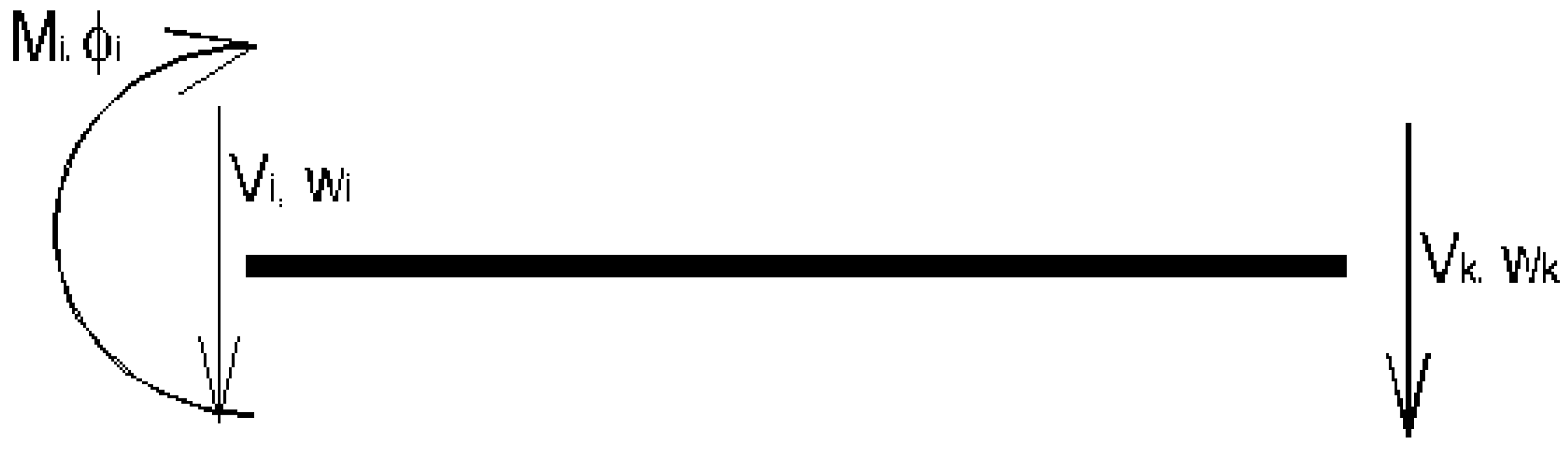

The sign convention adopted for the loads, bending moments, shear forces, and displacements is illustrated in

Figure 1

Let the displacements in x-, y-, and z- directions be denoted by u(

x,y,z), v(

x,y,z), and w(

x,y,z), respectively. Observing the symmetry of the cross-section with respect to the z-axis, these displacements can be described as follows

The kinematic and constitutive relations are

respectively, where E and G are the Young’s modulus and the shear modulus, respectively.

In the Levinson Beam Theory (LBT), the displacement field is such that the shear stresses/strains vanish on the upper and lower surfaces of the beam. In addition, it is assumed in this study that the maximal shear stresses/strains appear in the centroidal axis.

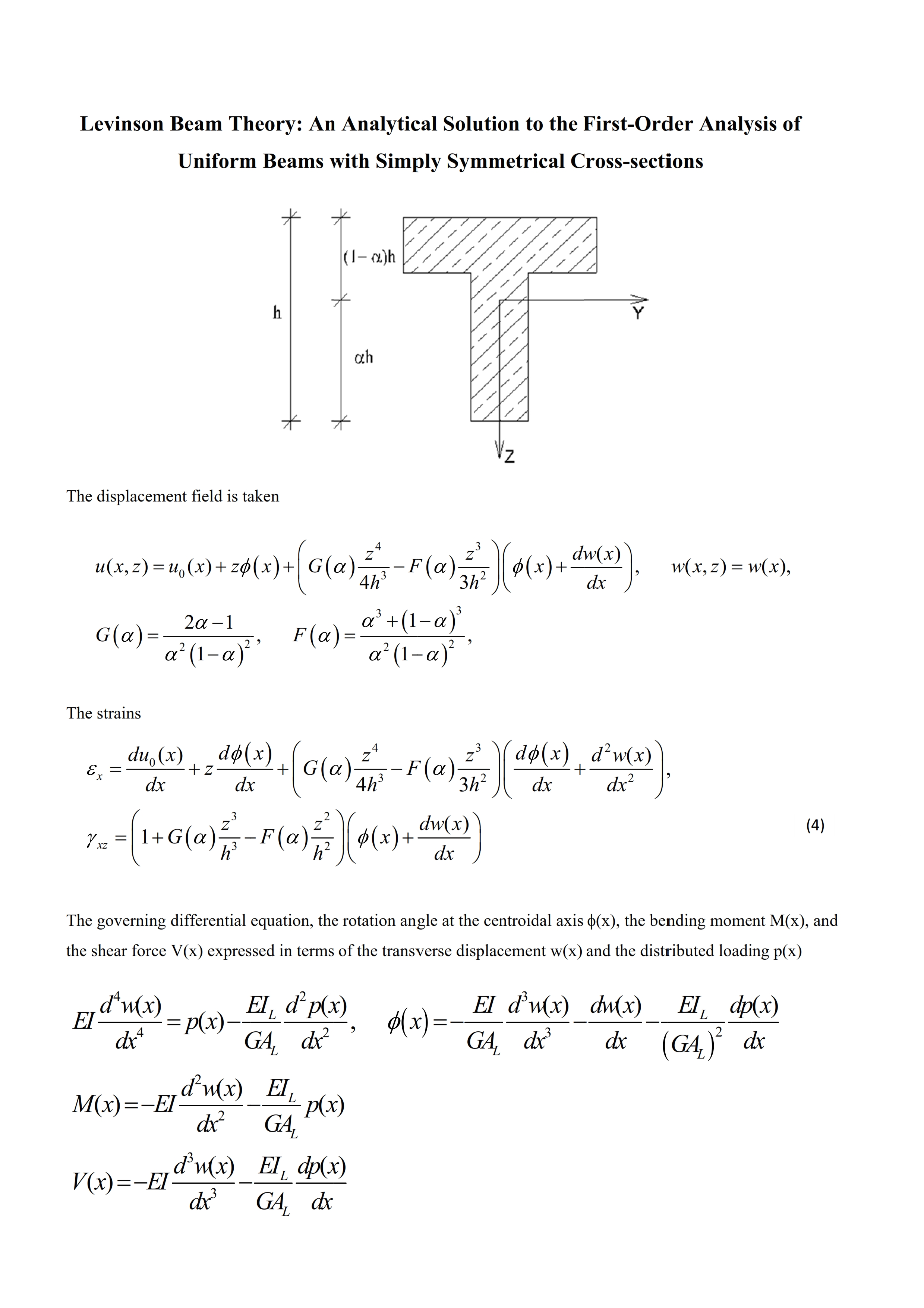

Letting the height of the beam be

h, and the

z coordinates of the lower and upper surface be z

l = α

h and z

u = - (1 - α)

h, respectively, the displacement field can then be taken

where u

0(x) is the displacement of the centroidal axis and φ(x) is the counterclockwise positive rotation of the cross-section at the centroidal axis. It is noted that for beams with double symmetrical cross sections α = 0.5 and the coefficients G(α) = 0, F(α) = 4, and so Equation (3) corresponds to the Levinson [

2] solution for beams of rectangular cross sections. It follows the strains using Equation (2)

The bending moment M(x), shear force V(x) and axial force N(x) are calculated using Equation (2) and (4) as follows

where A and I are the area and the second moment of area of the cross-section, respectively, and I

3, I

4, and I

5 are defined as I

n = ∫z

ndA with n = 3, 4, and 5. Let the following cross sectional values be

Deriving both sides of Equation (5b) with respect to x and combining with (6b) yields

Substituting Equation (7a) and (6a) into (5a) yields

Equation (7b) can be reformulated as follows to represent a moment − shear force − curvature relationship

In the case of non-uniform heating, Equation (7c) becomes

where α

T is the coefficient of thermal expansion, ΔT = ΔT

ls - ΔT

us is the difference between the temperature changes at lower surface (ΔT

ls) and upper surface (ΔT

us) of the beam, and

h is as before the height of the beam.

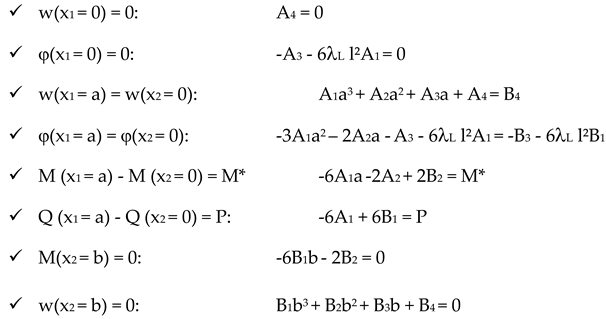

The static equilibrium equations in first-order analysis are given by

Equation (8a-c) are developed as follows using Equation (5a-c) and (6a-c)

Let us formulate Equation (8e-f) for beams with rectangular cross-sections. Recalling that G(α) = 0 and F(α) = 4

Equation (8h-i) are the equilibrium equations derived by Levinson [

2]. The bending moment can generally be expressed in terms of w(x) using Equation (7b) and (8b)

The shear force can also be expressed in terms of w(x) using Equation (8c) and (9)

Combining Equation (5b), (6b) and (10) yields

Combining Equation (8b-c) and (9) yields the governing differential equation of the uniform Levinson beam with simply symmetrical cross section

The governing differential equation (Equation 12), the bending moment M (Equation 9), the shear force V (Equation 10), and the rotation of the cross section (Equation 11) are expressed in terms of w(x): the analytical solution can then be found.

For illustration we consider a beam of length

l carrying a uniformly distributed load

p. The transverse deflection w(x) can be expressed as follows using Equation (12)

It follows the bending moment, the shear force V, and the rotation of the cross section

where λ

L is a bending shear factor. The integration constants C

1, C

2, C

3, and C

4 are then determined applying the boundary conditions expressed using Equation (13) and (14a-d). Results for some cases are presented in

Appendix A.

It is noted that w(x) and φ(x) are determined independently from u

0(x). The latter is found from the following governing equation (8d) using (8e)

and the boundary conditions involving the axial force N(x) and u

0(x) at the beam’s ends.

Table 1 summarizes the Euler–Bernoulli beam equations, Timoshenko beam equations, and Levinson beam equations in terms of the transverse deflection w(x), whereby the rotation of cross-sections is counterclockwise positive and the Timoshenko shear coefficient is κ.

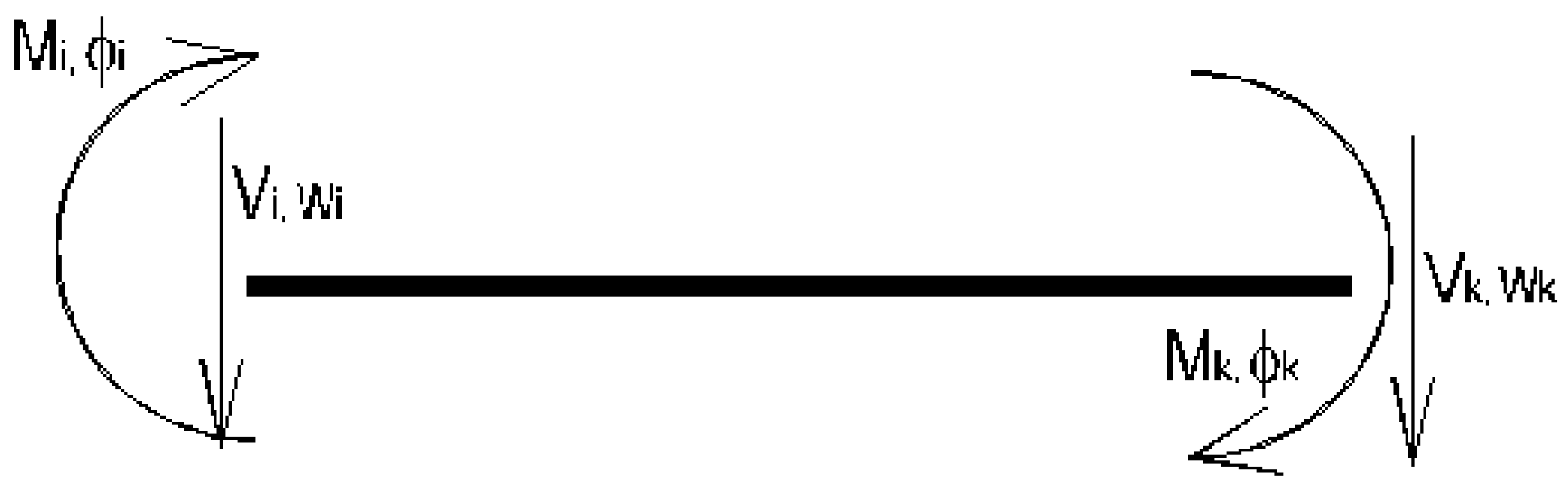

2.3. Element Stiffness Matrix

The sign convention for bending moments, shear forces, displacements, and rotation angles adopted for determining the element stiffness matrix in local coordinates is illustrated in

Figure 2.

Let us define the element-end force vector and the element-end displacement vector as follows

The element stiffness matrix in local coordinates of the Levinson beam is denoted by K

Ll. The relationship between the aforementioned vectors is as follows:

Applying Equation (14a-d) with the distributed load p = 0 yields the following

Considering the sign conventions adopted for bending moments and shear forces in general (see

Figure 1) and for bending moments and shear forces in the element stiffness matrix (see

Figure 2), we can set following static compatibility boundary conditions in combination with Equation (21a-d)

Considering the sign conventions adopted for the displacements (see

Figure 1) and rotations (counterclockwise positive) on the one hand and for displacements and rotations in the member stiffness matrix (see

Figure 2) on the other hand, we can set following geometric compatibility boundary conditions in combination with Equation (21a-d)

Combining Equation (20), (22a-d) and (23a-d) yields the 4 × 4 first-order element stiffness matrix of the Levinson beam

The development of Equation (24) yields

The element stiffness matrix (ESM) of the Levinson beam has the same formulation as that of the Timoshenko beam whereby the coefficients in the matrices are related as follows: ALΦL = κAΦT. The ESM of the Euler−Bernoulli beam is obtained by setting ΦL = 0.

Assuming the presence of a hinge at the right end, the sign convention for bending moments, shear forces, displacements, and rotations is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The element-end force vector and the element-end displacement vector become

The analysis is done similarly and the 3 × 3 element stiffness matrix of the Levinson beam is then

As before the element stiffness matrix of the Levinson beam has the same formulation as that of the Timoshenko beam whereby the coefficients in the matrices are related as follows: ALλL = κAλT.

2.4. Strong and Weak Formulation of the Boundary Conditions

The analytical solution presented in this paper satisfies the boundary conditions (BC’s) through the stress resultants (axial force, shear force and bending moment) and the rotation of cross-section only at the centroidal axis: this represents a weak formulation of the BC’s. Strong formulations of the BC’s expressed in terms of stresses and displacements are listed below for different edge conditions whereby the displacement component u0(x) is ignored since it does not contribute to M(x) and V(x).

Clamped Edge

From the strong formulation the displacements u(x, z) and w(x) are zero at any position z. From Equation (3) it yields φ = 0, dw/dx = 0, w = 0. Consequently the shear stresses and the shear force vanish regarding Equation (4) and (5b), this representing an inconsistency. By applying a weak formulation of the BC’s (φ = 0, w = 0) this inconsistency disappears.

Free Edge

The strong formulation implies the normal and shear stresses σ and τ are zero at any position z. Equation (15a-b) yields dφ/dx = 0, p(x) = 0, φ + dw/dx = 0. Hence, the absence of distributed loading is a condition for the satisfaction in a strong sense of the BC’s. The weak formulation is M = 0, V = 0.

Simply Supported Edge

From the strong formulation the normal stresses σ = 0 and the transverse deflection w = 0 at any position z. Equation (15a-b) implies dφ/dx = 0, p(x) = 0, w = 0. The absence of distributed loading is a condition for the satisfaction in a strong sense of the BC’s. The weak formulation is M = 0, w = 0.

In summary, on the one hand it is observed that the strong formulation of the BC’s is characterized with three conditions: this required a beam model described with a sixth-order governing differential equation. On the other hand the weak formulation is characterized with two conditions at each edge, which is consistent with the fourth-order governing differential equation of the Levinson beam model.

2.5. Inconsistencies in the Determination of Shear Stresses

In this study the shear stresses were determined using the stress-strain relationship or constitutive law (Equation (2d)). However they can be calculated using the equilibrium-method as it is done in the Euler−Bernoulli beam theory. Here a beam element obtained by performing plane cuts at

x,

x + d

x, and

z is considered. The equilibrium equation in x direction is set on this element using Equation (15a-b) for stresses, i.e., the shear stresses τ

zx = τ

xz have to balance-out the variation of the axial force apart from

z as follows

The term on the right-hand side of Equation (28) is a fifth-order polynomial with respect to z while τxz (Equation (15b)) is a third-order polynomial with respect to z.

Therefore, similarly to Euler−Bernoulli beam theory and Timoshenko beam theory, an inconsistency remains between the shear stresses that are obtained based on the equilibrium-method and the shear stresses obtained by the constitutive law.