Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Animal Experiments

2.3. Vaccines

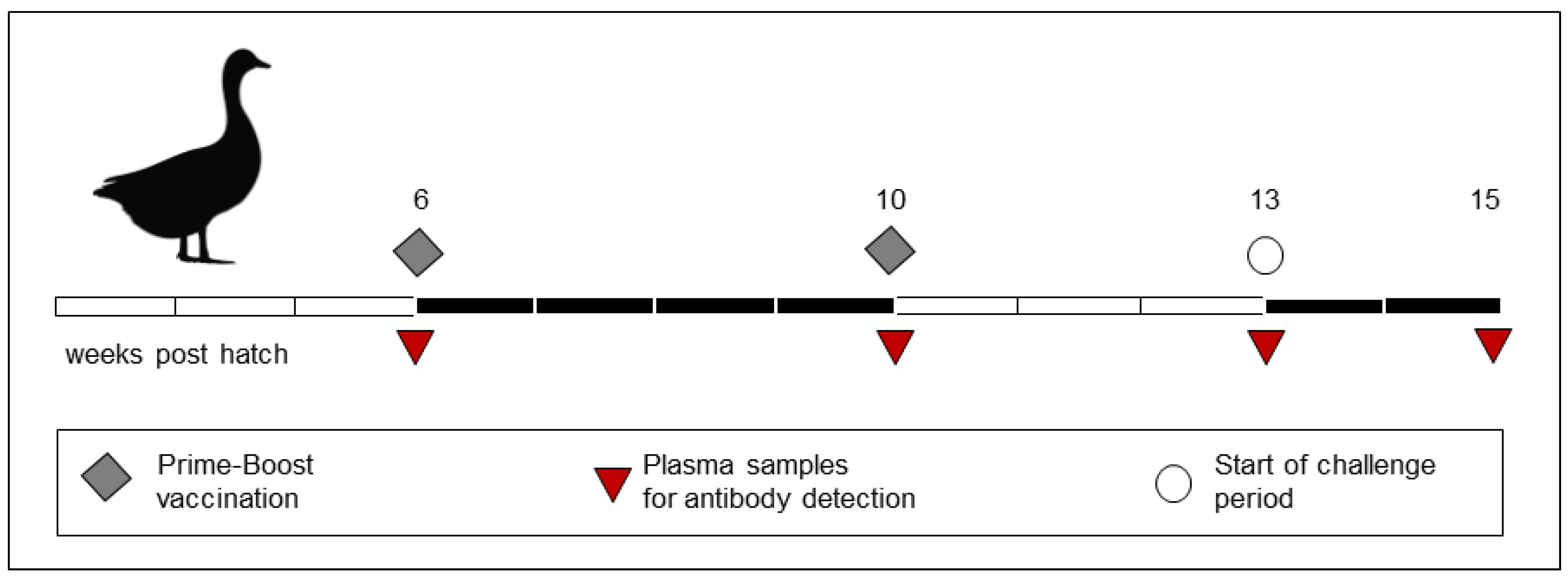

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Virus

2.6. Serology

2.7. Challenge Experiment

2.8. Real-Time RT-PCR

2.9. Virus Isolation from Clinical Materials

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Safety and Immunogenicity

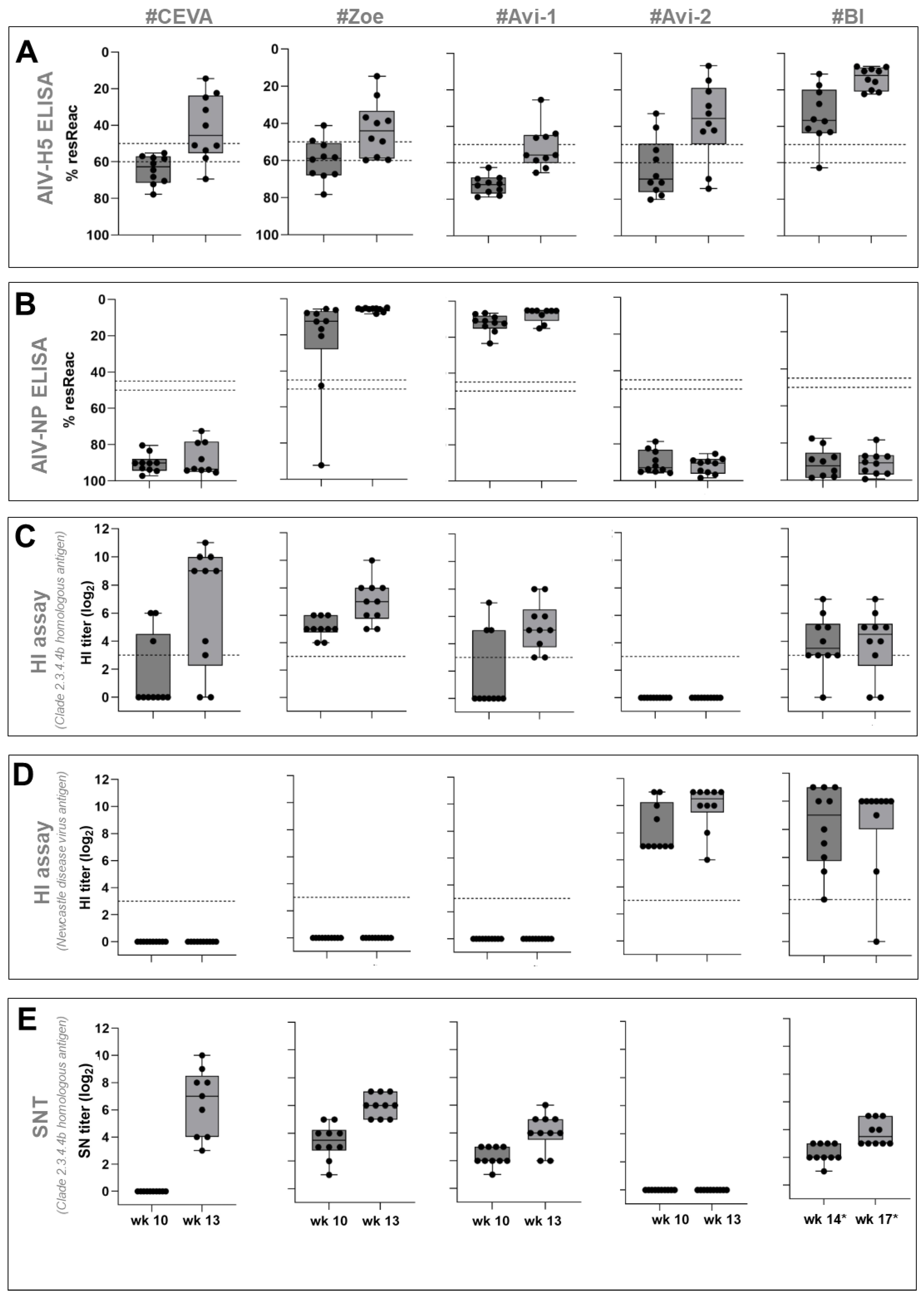

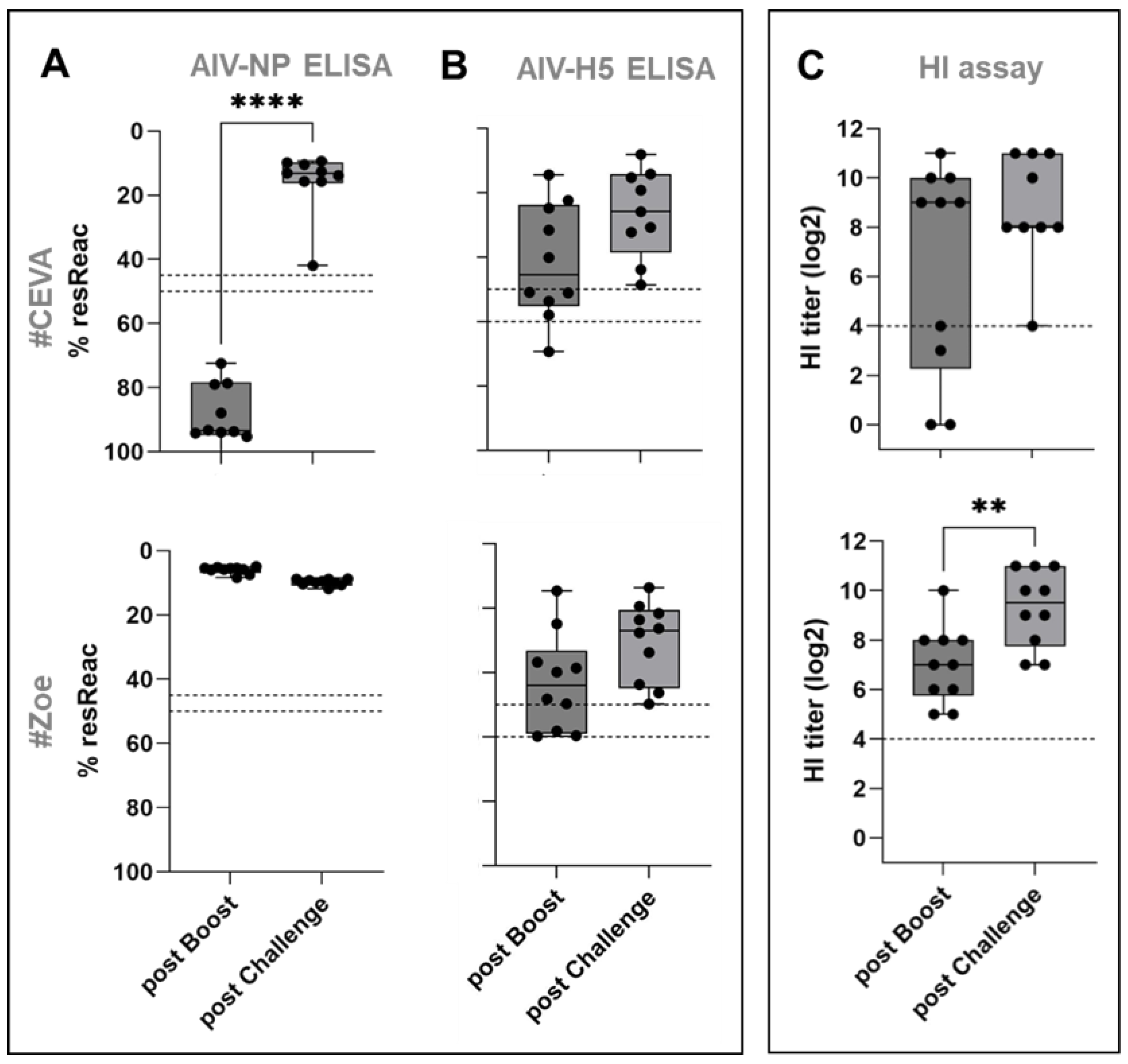

3.1.1. AI Virus H5-ELISA:

3.1.2. AI Virus NP-ELISA:

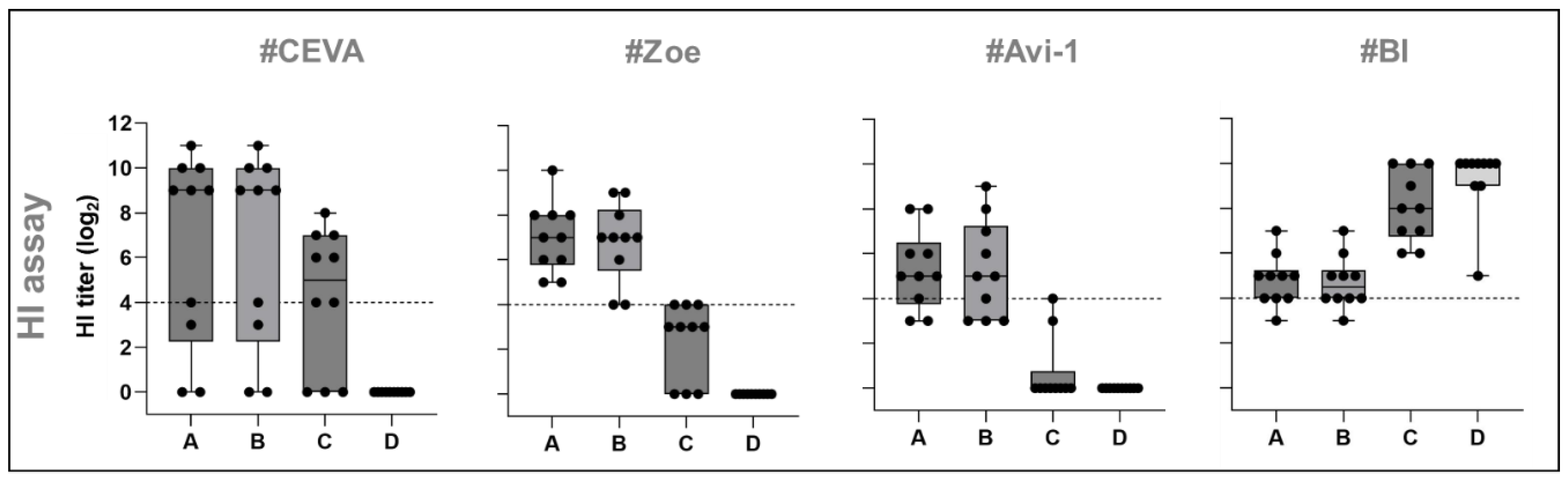

3.1.3. HI Assay

3.1.4. SNT Assay

3.2. Protective Efficacy Against Homologous Challenge

3.2.1. Full Clinical Protection in Seropositive Vaccinees

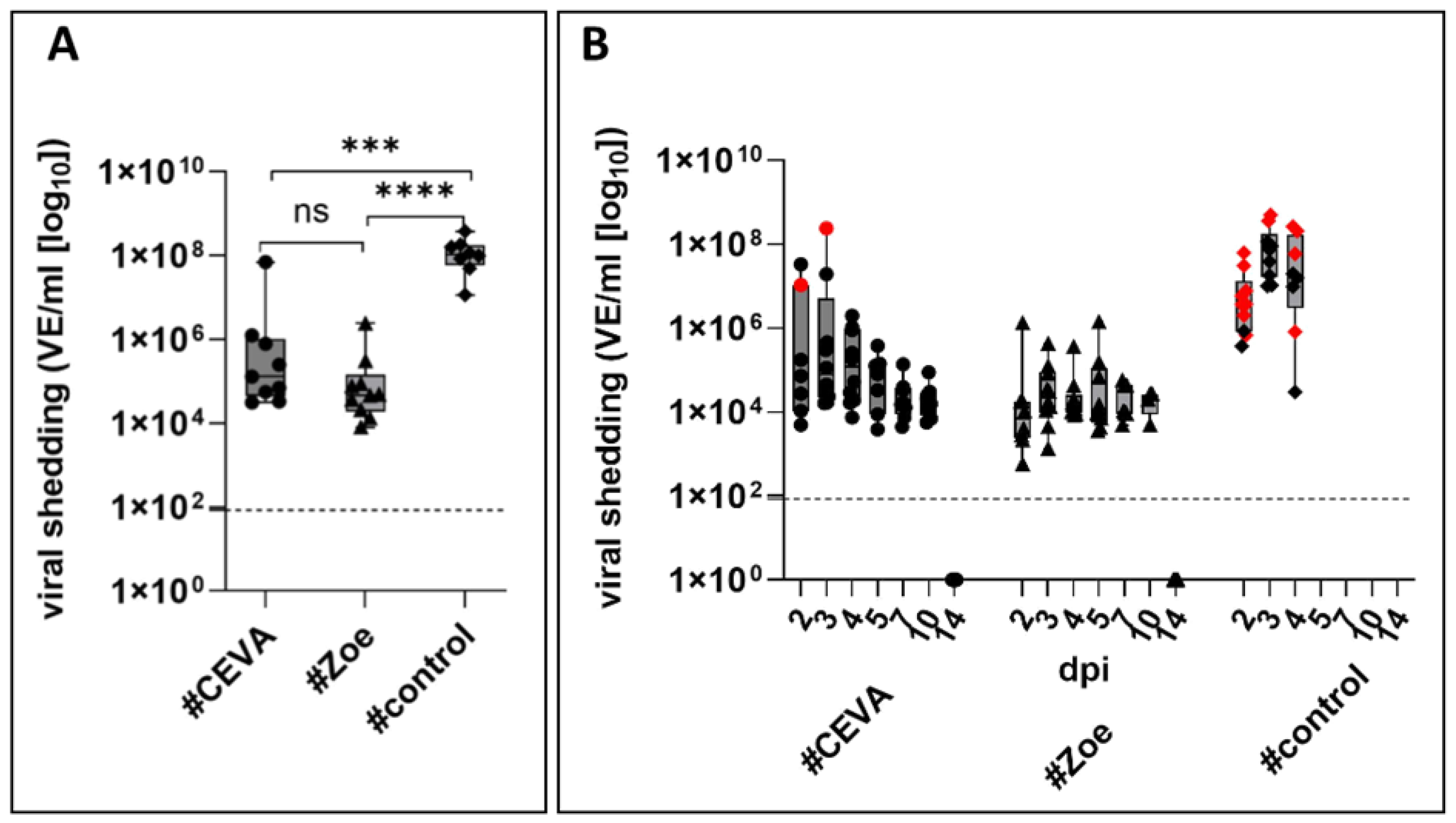

3.2.2. Vaccination Reduced Virus Shedding

3.2.3. Failure to Isolate Virus in Cell Culture from Swabs of Vaccinated Geese

3.2.4. AIV Infection Was Cleared in Vaccinated, Seropositive Geese

3.2.5. NP-Specific Seroconversion as a Serological DIVA Surveillance Tool

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSL 3 | Biosafety Level 3 |

| CPE | cytopathic effect |

| DIVA | Differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals |

| FCS | Fetal calf serum |

| FLI | Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute |

| gs/GD | Goose/Guandong |

| HA | Haemagglutinin |

| HA | Hemagglutination assays |

| HI | Hemagglutination inhibition assay |

| HPAI | Highly patogenic avian influenza |

| HPAIV | Highly patogenic avian influenza virus |

| IFN | Interferon |

| LMH | Leghorn male hepatoma |

| MTA/NDA | Material Transfer Agreement/ Non-Disclosure Agreement |

| NDV | Newcastle Disease Virus |

| SNT | Serum Neutralization test |

| SPF | Specific-pathogen-free |

| TCID | Tissue-culture-infection dose |

| VE | Viral equivalents |

References

- Alders, R., Awuni, J. A., Bagnol, B., Farrell, P. & Haan, N. de. Impact of avian influenza on village poultry production globally. EcoHealth 2014, 11, 63–72. [CrossRef]

- Hautefeuille, C. Hautefeuille, C., Dauphin, G. & Peyre, M. Knowledge and remaining gaps on the role of animal and human movements in the poultry production and trade networks in the global spread of avian influenza viruses - A scoping review. PloS one 2020, 15, e0230567. [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, J. H., Fouchier, R. A. M. & Lewis, N. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses at the Wild-Domestic Bird Interface in Europe: Future Directions for Research and Surveillance. Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, M. & Wille, M. The plight and role of wild birds in the current bird flu panzootic. Nature ecology & evolution 2023, 7, 1541–1542. [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, M. P. G. et al. The panzootic spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 sublineage 2.3.4.4b: a critical appraisal of One Health preparedness and prevention. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2024. [CrossRef]

- Delpont, M. et al. Monitoring biosecurity in poultry production: an overview of databases reporting biosecurity compliance from seven European countries. Frontiers in veterinary science 2023, 10, 1231377. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K. E. et al. Improved Subtyping of Avian Influenza Viruses Using an RT-qPCR-Based Low Density Array: 'Riems Influenza a Typing Array', Version 2 (RITA-2). Viruses 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Report. Avian influenza overview December 2022 - March 2023. EFSA Journal 2023, 21, e07917. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Report. Drivers for a pandemic due to avian influenza and options for One Health mitigation measures. EFSA Journal 2024, 22, e8735. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, N. S. et al. Antigenic evolution of contemporary clade 2.3.4.4 HPAI H5 influenza A viruses and impact on vaccine use for mitigation and control. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3794–3798. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Animal Welfare (AHAW), European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza. Vaccination of poultry against highly pathogenic avian influenza - part 1. Available vaccines and vaccination strategies. EFSA journal. European Food Safety Authority 2023, 21, e08271. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Animal Welfare (AHAW), European Union Reference Laboratory for Avian Influenza. Vaccination of poultry against highly pathogenic avian influenza - Part 2. Surveillance and mitigation measures (2024).

- Harder, T. et al. Epidemiology-driven approaches to surveillance in HPAI-vaccinated poultry flocks aiming to demonstrate freedom from circulating HPAIV. Biologicals: journal of the International Association of Biological Standardization 2023, 83, 101694. [CrossRef]

- French Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty. Arrêté Ministériel du 25 septembre 2023 relatif aux mesures de surveillance, de prévention, de lutte et de vaccination contre l’influenza aviaire hautement pathogène (IHAP). [Ministerial decree of 25 September 2023 as regards surveillance, prevention, intervention and vaccination measures against highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI)] (2023).

- French Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty. Influenza aviaire: le plan de vaccination de la France. [Avian influenza: France’s vaccination plan. 2024. Available online: https://agriculture.gouv.fr/tout-ce-quil-faut-savoir-sur-le-plan-daction-vaccination-iahp-en-france.

- Guinat, C. et al. Promising effects of duck vaccination against highly pathogenic avian influenza, France 2023-24 (2024).

- Oliveira Cavalcanti, M. et al. A genetically engineered H5 protein expressed in insect cells confers protection against different clades of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses in chickens. Avian pathology: journal of the W.V.P.A 2017, 46, 224–233. [CrossRef]

- Piesche, R. et al. Dominant HPAIV H5N1 genotypes of Germany 2021/2022 are linked to high virulence in Pekin ducklings. npj Viruses 2024, 2. [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, D.J. Highly pathogenic avian influenza. In Manual of Standards for Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines, 4th ed.; Office International des Epizooties: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- WOAH. Terrestrial Manual on Avian Influenza (Chapter 3.3.4) (2023).

- Ahrens, A. K., Selinka, H.-C., Mettenleiter, T. C., Beer, M. & Harder, T. C. Exploring surface water as a transmission medium of avian influenza viruses - systematic infection studies in mallards. Emerging microbes & infections 2022, 11, 1250–1261. [CrossRef]

- Spackman, E. & Swayne, D. E. Vaccination of gallinaceous poultry for H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza: current questions and new technology. Virus research 2013, 178, 121–132. [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T. & Yoshioka, Y. Considerations of CD8+ T Cells for Optimized Vaccine Strategies Against Respiratory Viruses. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 918611. [CrossRef]

- Roth, G. A. et al. Designing spatial and temporal control of vaccine responses. Nature reviews. Materials 2022, 7, 174–195. [CrossRef]

- Borriello, F. et al. An adjuvant strategy enabled by modulation of the physical properties of microbial ligands expands antigen immunogenicity. Cell 2022, 185, 614-629.e21. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. et al. Mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity to the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine. Nature immunology 2022, 23, 543–555. [CrossRef]

- Reemers, S. S. N., van Haarlem, D. A., Sijts, A. J. A. M., Vervelde, L. & Jansen, C. A. Identification of novel avian influenza virus derived CD8+ T-cell epitopes. PloS one 2012, 7, e31953. [CrossRef]

- Reemers, S., Verstegen, I., Basten, S., Hubers, W. & van de Zande, S. A broad spectrum HVT-H5 avian influenza vector vaccine which induces a rapid onset of immunity. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1072–1079. [CrossRef]

- Germeraad, E. A. et al. Transmissiestudie met vier vaccins tegen H5N1 hoogpathogeen vogelgriepvirus (clade 2.3.4.4b). CVI Virology, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cha, R. M. et al. Suboptimal protection against H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses from Vietnam in ducks vaccinated with commercial poultry vaccines. Vaccine 2013, 31, 4953–4960. [CrossRef]

- Poetri, O. N. et al. Silent spread of highly pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 virus amongst vaccinated commercial layers. Research in veterinary science 2014, 97, 637–641. [CrossRef]

- Elbers, A. R. W. & Gonzales, J. L. Mortality Levels and Production Indicators for Suspicion of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus Infection in Commercially Farmed Ducks. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, D.L.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Immunology of avian inuenza virus: a review. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1999, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, M.E. Concepts of transmission and dynamics. In Epidemiologic Methods for the Study of Infectious Diseases.; 2001; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

| Group | Vaccine producer | Vaccine name | Batch number | Type [gs/GD clade] | Dose and application | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Ceva | CEVA | RESPONS AI H5 | Lot 0409LF | Amplicon (H5) [2.3.4.4b] |

0.2 ml | i.m. caudal femoral muscle |

| #Zoe | Zoetis | NE 69521 LO523AS03 | WIV (H5N2) [2.3.4.4b] |

0.5 ml | s.c. neck fold | |

| #Avi-1 | Avimex | Vaxigen Flu H5N8 clado 2.3.4.4 | Reg B-0258-131 | WIV (H5N8) [2.3.4.4b] |

0.5 ml | s.c. neck fold |

| #Avi-2 | Avimex | KNewH5 | Lote E.PM-2304 | recNDV (H5) [2.3.4.4b] |

0.5 ml | s.c. neck fold |

| #BI | Boehringer | Volvac B.E.S.T. AI+ND | 2307011A | Baculovirus-based expression system of an inserted optimized H5 sequence for antigen formulation | 0.5 ml | s.c. neck fold |

| Sub-and phenotype | Clade | Isolate | Sequence accession | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | HP H5N1 | 2.3.4.4b | A/chicken/Germany-NI/AI 4286/2022 | Epi16096050 |

| B | HP H5N1 | 2.3.4.4b | A/chicken/Germany-SH/AI08298/2021 | Epi18006820 |

| C | HP H5N1 | 1.0 | A/chicken/Vietnam/P41-05/2005 (R75/05) | Epi13970 |

| D | NDV | Genotype 2.II | NDV LaSota | ON713864 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).