Submitted:

08 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

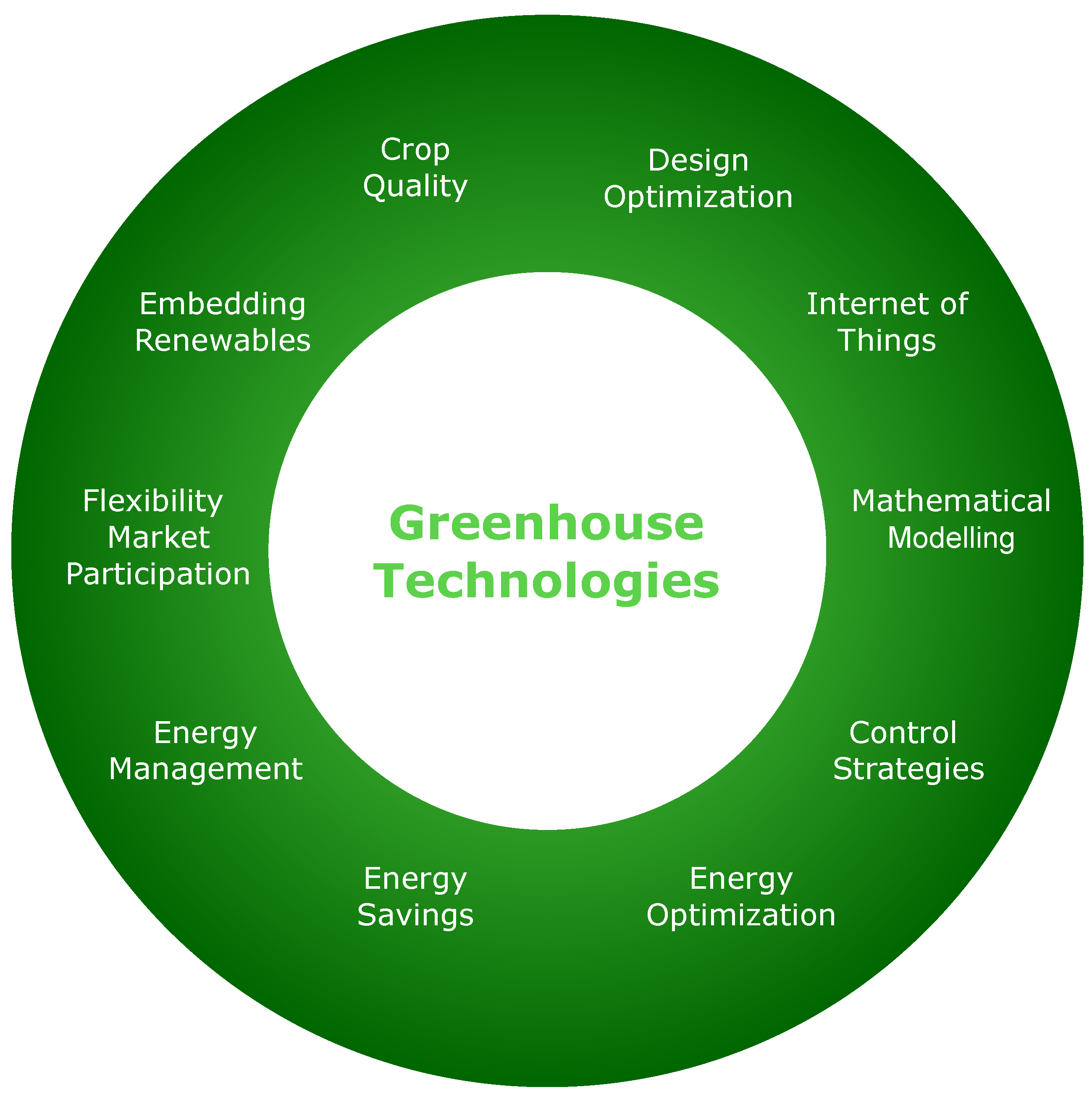

1. Introduction

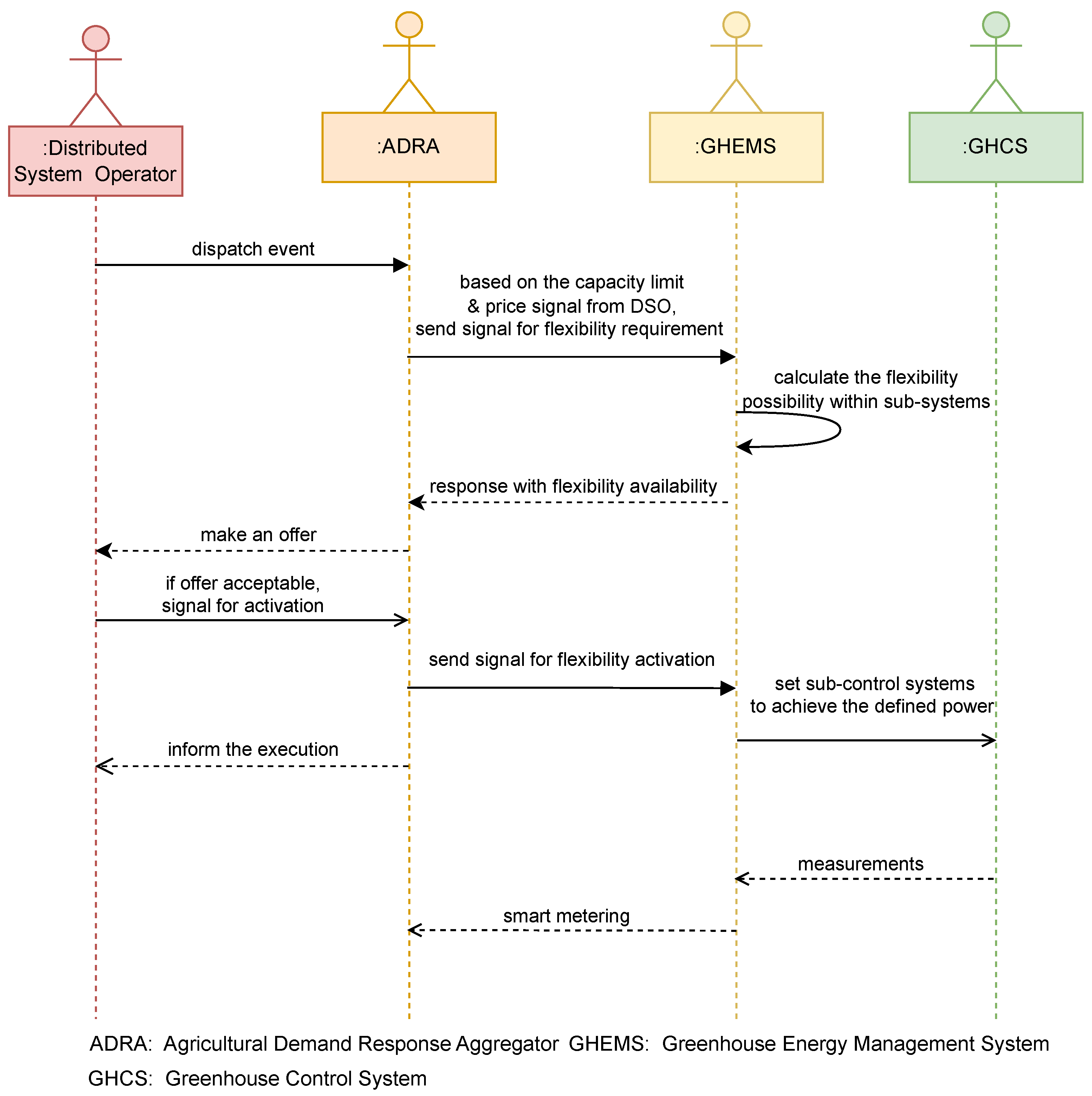

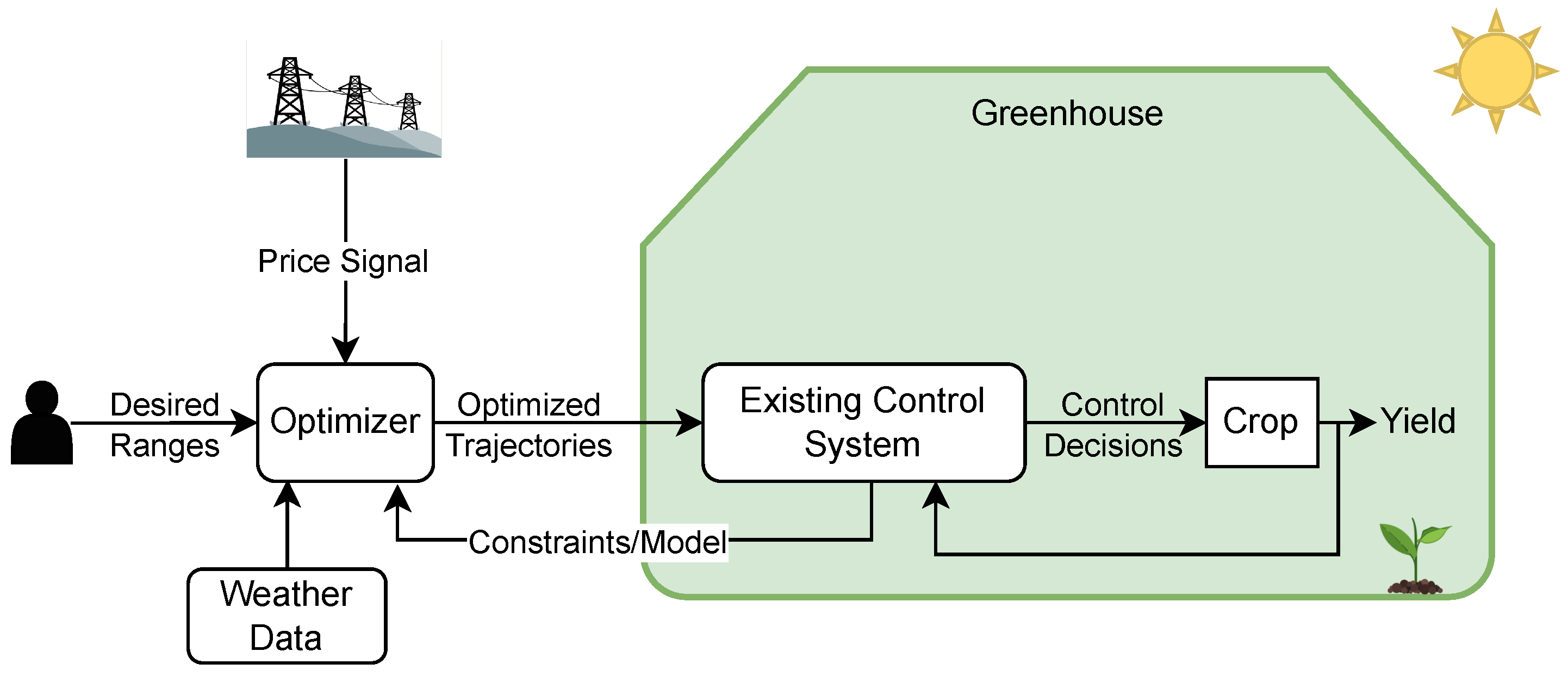

2. Greenhouse Energy Management in Smart Grid Context

3. Greenhouse Microclimate

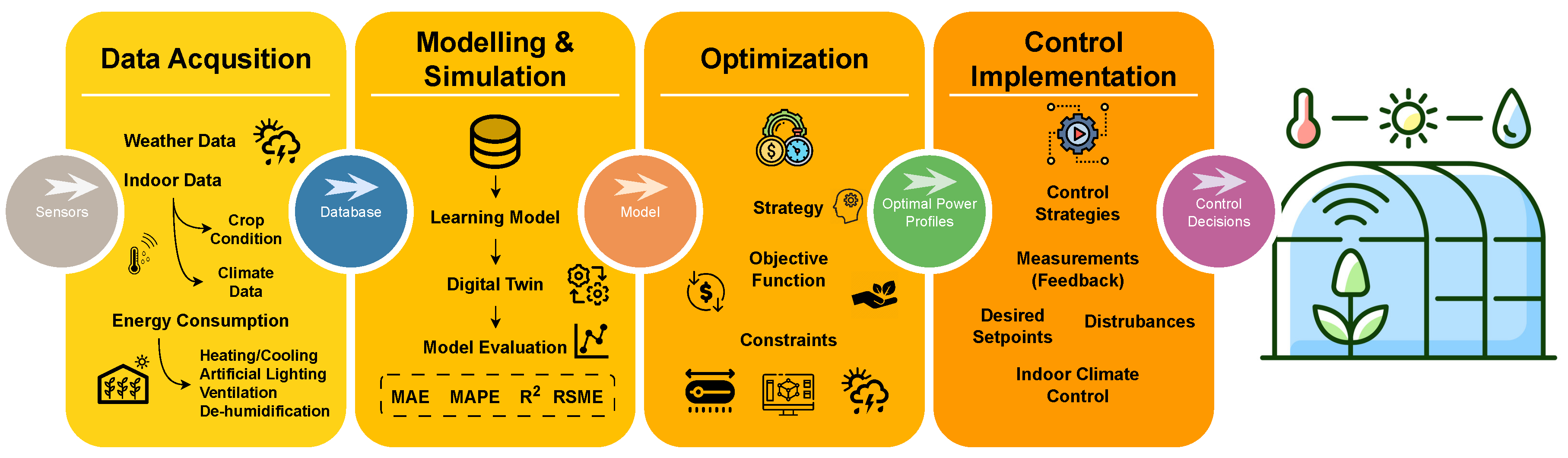

3.1. Sensors & Data Acquisition

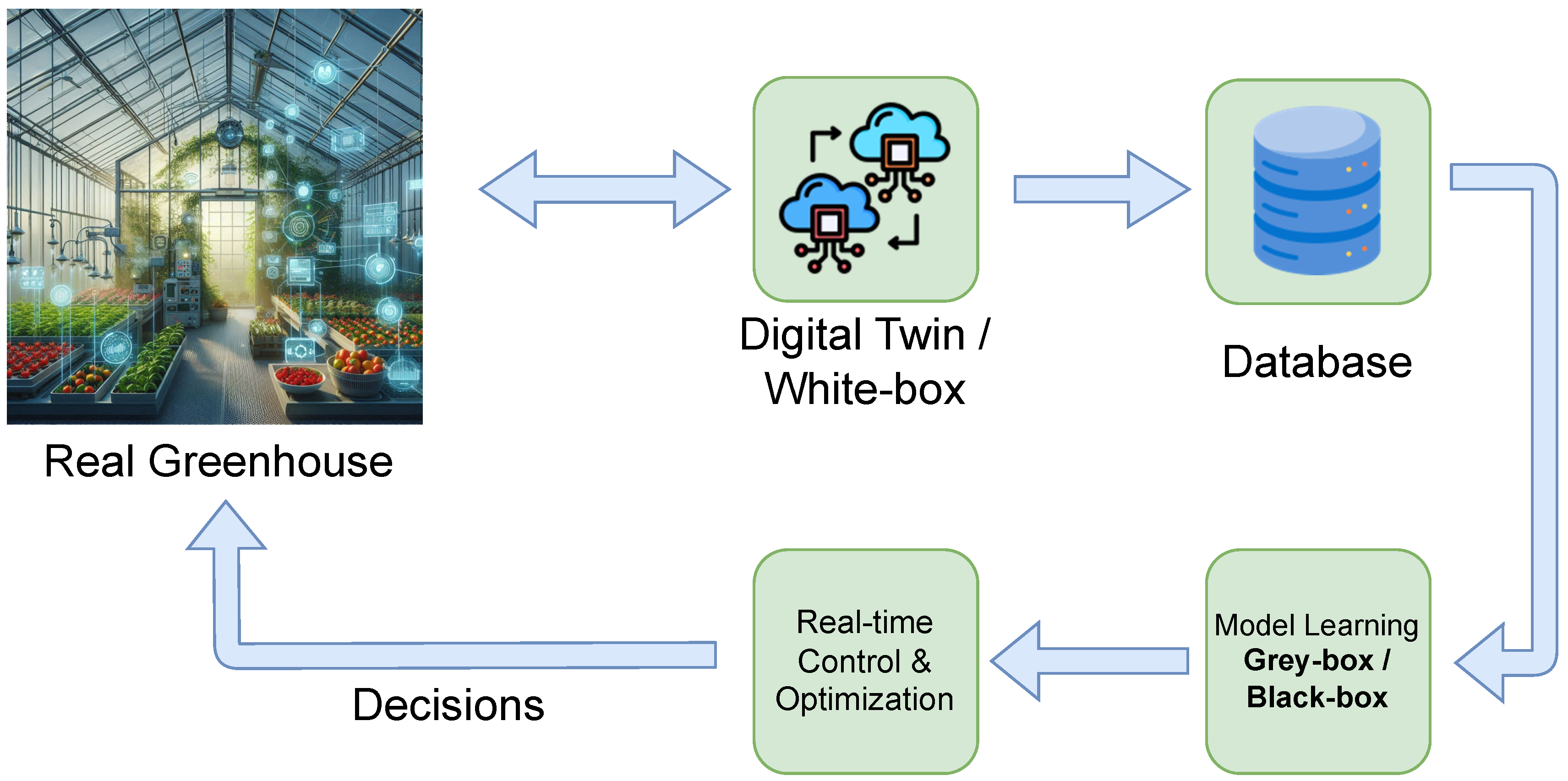

3.2. Modelling & Simulation

3.2.1. White Box

- Detailed Process Insight: Provides a comprehensive insight into the dynamics, enhancing understanding of every aspect of the system.

- Predictive Precision: Considering that all the details are rightfully mentioned and understood, it can provide extremely precise predictions of the system under study, making them ideal for DTs.

- Customizability: It can customized to the specific systems and conditions, allowing tailored solutions.

- Reliability: Complimentary to the precision, they provide reliable results under perfect details.

- Controllability: Higher controllability at a granular level.

- Complexity: As the number of variables grows, model complexity increases, demanding greater domain-specific knowledge and expertise.

- Sensitivity to Parameter Change: Model accuracy and stability can be questionable due to the model sensitivity to the parameter change.

- Time Expense: Describing the system’s aspects is tedious and time-consuming, making it computationally expensive.

- Adaptation Difficulty: Challenging to adapt quickly to new or significantly changing conditions without extensive recalibration or redevelopment.

3.2.2. Grey Box

- Development Time: Compared to white box models, grey box models take less time owing to the partial dependence on empirical data.

- Robustness: More robust to the stochasticity of the variables, such as the climate conditions, compared to black box models, enhancing crop yield predictions.

- Management: Combining simplified plant growth models and data can improve environmental management.

- Calibration Complexity: Robust parameter estimation methods are required to improve accuracy, which is one of the major challenges of grey box models.

- Computational Demand: The complexity of the model’s physical part and the objective function’s complexity can make them computationally expensive.

- Re-calibration: Periodic re-calibration is required with more recent data.

- Moderate Data and Knowledge Requirement: Though better than the black box model, it might be challenging to fit sometimes if the training period is too long. Additionally, appropriate knowledge is necessary as some of the sub-processes can have analogy or empirical

3.2.3. Black Box

- Rapid Deployment: Quick to implement for real-time monitoring and control based on historical data.

- Cost-effective: Lower initial cost is one of the major benefits of black box models as they do not require domain-specific knowledge.

- Flexible and Scalable: Large dataset handling capacity and swiftly transformable to state space formulation for control applications.

- Generalization: Cannot be generalized as they are vulnerable to uncertain conditions previously not encountered.

- Data Dependent: As no physics-based knowledge is involved, they are highly dependent on data and can lead to inaccuracies for certain processes where knowledge is paramount, for instance, plant growth patterns or anomalies.

- Trust Issues: Lack of insights can limit understanding of predictions.

3.3. Control & Optimization

4. Discussions and Future Research

4.1. Future Research Opportunities

4.1.1. Crop Model

4.1.2. Integrated Modeling Approach

4.1.3. Smart Grid Inclined Management

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| ADF | Affine Disturbance Feedback |

| ADRA | Agricultural Demand Response Aggregator |

| AL | Artificial Lighting |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BESS | Battery Energy Storage System |

| CDW | Crop Dry Weight |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DDPG | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| DTiPS | Digital Twins in Power Systems |

| DR | Demand Response |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DSO | Demand Side Operator |

| EC | Energy Cost |

| EA | Evolutionary Algorithm |

| GHCS | Greenhouse Control System |

| GHEMS | Greenhouse Energy Management System |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, Air Conditioning |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IPOPT | Internal-point Optimizer |

| LSTM | Long Short Term Memory |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MILP | Mixed-integer Programming |

| NDR | Node Development Rate |

| NN | Neural Network |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SMC | Sliding Mode Control |

| SP | Set Point |

| TE | Transactive Energy |

| TESS | Thermal Energy Storage System |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| WP | Water Pump |

| Greek Symbols | |

| Air density | |

| Efficiency of solar radiation conversion | |

| Efficiency of crop light interception | |

| Psychrometric constant | |

| Slope of the saturation vapor pressure curve | |

| Coefficient for transpiration rate | |

| Laplacian operator | |

| Growth coefficient for LAI | |

| Coefficient for uptake rate | |

| Latent heat of vaporization | |

| Variables | |

| Mass flow rate of water vapor entering | |

| Mass flow rate of water vapor leaving | |

| Mass flow rate of water vapor due to evaporation | |

| Mass flow rate of water vapor due to condensation | |

| Mass flow rate of water vapor due to transpiration | |

| Mass flow rate of water drainage | |

| Mass flow rate of water uptake by plants | |

| Mass flow rate of uptake by plants | |

| Mass flow rate of air | |

| Mass flow rate of entering the greenhouse | |

| Mass flow rate of exiting the greenhouse | |

| Mass flow rate of water vapor due to ventilation | |

| Effective area of the crop canopy | |

| Area of the greenhouse glazing | |

| Specific heat of air | |

| Thermal capacitance of indoor air | |

| Thermal capacitance of the crop canopy | |

| Thermal capacitance of the soil | |

| Indoor concentration | |

| External concentration | |

| Vapor pressure deficit | |

| G | Soil heat flux density |

| External humidity | |

| Indoor humidity | |

| Soil humidity | |

| Incident solar radiation | |

| k | Extinction coefficient for light interception |

| Thermal conductivity of the soil | |

| L | Leaf Area Index (LAI) |

| Maximum LAI | |

| Power of the artificial lighting system | |

| Heat removal by the cooling system | |

| Heat exchange with the soil and plants | |

| Heating input from the heating system | |

| Heat generated by artificial lighting | |

| Heat loss to deeper soil layers or surroundings | |

| Solar heat gain | |

| Solar heat absorbed by the crop canopy | |

| Latent heat loss due to transpiration | |

| Net radiation at the crop surface | |

| Crop canopy temperature | |

| Indoor temperature | |

| Temperature of artificial lighting | |

| Soil Temperature | |

| Indoor air volume | |

| Volume of soil | |

| Aerodynamic resistance | |

| Stomatal resistance | |

| Duration of artificial lighting |

References

- U. N.. Global Issues: Population, 2023.

- Doering, O.; Sorensen, A. The land that shapes and sustains us. How to Feed the World. [CrossRef]

- Drottberger, A.; Zhang, Y.; Yong, J.W.H.; Dubois, M.C. Urban farming with rooftop greenhouses: A systematic literature review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 188, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jia, N.; Lenzen, M.; Malik, A.; Wei, L.; Jin, Y.; Raubenheimer, D. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nature Food 2022, 3, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.A.; Domingo, N.G.; Colgan, K.; Thakrar, S.K.; Tilman, D.; Lynch, J.; Azevedo, I.L.; Hill, J.D. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the 1.5∘ and 2∘C climate change targets. Science 2020, 370, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer-Nawrocka, A.; Sadowski, A. Food security and food self-sufficiency around the world: A typology of countries. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, K. Canada ’ s fruit & vegetable supply at sub-national scale : A first step to understanding vulnerabilities to climate change 2023.

- Tawalbeh, M.; Aljaghoub, H.; Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.G. Selection criteria of cooling technologies for sustainable greenhouses: A comprehensive review. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2023, 38, 101666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahdev, R.K.; Kumar, M.; Dhingra, A.K. A comprehensive review of greenhouse shapes and its applications. Frontiers in Energy 2019, 13, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, S.; Bakochristou, F.; ElBialy, E.M.A.A.; Gamaledin, S.M.A.; Rashwan, M.M.; Abdelhalim, A.M.; Ismail, S.M. Design challenges of agricultural greenhouses in hot and arid environments. Engineering in Agriculture, Environment and Food 2019, 12, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, T.; Wang, W.; Jia, X.; Wang, J.; Klemeš, J.J. Energy-saving design and control strategy towards modern sustainable greenhouse: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydro-Québec. What happens when electricity use exceeds the grid’s capacity?, 2024.

- Decardi-Nelson, B.; You, F. Optimal energy management in greenhouses using distributed hybrid DRL-MPC framework. In 33 European Symposium on Computer Aided Process Engineering; Kokossis, A.C.; Georgiadis, M.C.; Pistikopoulos, E.B.T.C.A.C.E., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; Vol. 52, pp. 1661–1666. [CrossRef]

- Hydro-Québec. Action Plan 2035 – Towards a Decarbonized and Prosperous Québec. Technical report, 2023.

- Golzar, F.; Heeren, N.; Hellweg, S.; Roshandel, R. A novel integrated framework to evaluate greenhouse energy demand and crop yield production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 96, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; Mattson, N.S.; You, F. Energy-efficient AI-based Control of Semi-closed Greenhouses Leveraging Robust Optimization in Deep Reinforcement Learning. Advances in Applied Energy 2023, 9, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Mattson, N.S.; You, F. Intelligent control and energy optimization in controlled environment agriculture via nonlinear model predictive control of semi-closed greenhouse. Applied Energy 2022, 320, 119334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, B.; Vandorou, F.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Vaiopoulos, K.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G. Energy Use in Greenhouses in the EU: A Review Recommending Energy Efficiency Measures and Renewable Energy Sources Adoption. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badji, A.; Benseddik, A.; Bensaha, H.; Boukhelifa, A.; Hasrane, I. Design, technology, and management of greenhouse: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 373, 133753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebey, A.H. Recent advancement in demand side energy management system for optimal energy utilization. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 5422–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouadila, S.; Baddadi, S.; Ben Ali, R.; Ayed, R.; Skouri, S. Deploying low-carbon energy technologies in soilless vertical agricultural greenhouses in Tunisia. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2023, 42, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Amponsah, W.; Oteng-Darko, P.; Osei, G. Safeguarding food security through large-scale adoption of agricultural production technologies: The case of greenhouse farming in Ghana. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2022, 6, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, G.; Kosatica, E.; Berger, M.; Kissinger, M.; Fridman, D.; Koellner, T. Domestic water versus imported virtual blue water for agricultural production: A comparison based on energy consumption and related greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Industrial Ecology 2023, 27, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayyum, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Li, S.; Ahmad, W.; Maodaa, S.N.; Sayed, S.R.; Gan, J. Advancements in technology and innovation for sustainable agriculture: Understanding and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural soils. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 347, 119147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Harjunowibowo, D.; Cuce, P.M. Renewable and sustainable energy saving strategies for greenhouse systems: A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 64, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorjian, S.; Calise, F.; Kant, K.; Ahamed, M.S.; Copertaro, B.; Najafi, G.; Zhang, X.; Aghaei, M.; Shamshiri, R.R. A review on opportunities for implementation of solar energy technologies in agricultural greenhouses. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddio, E.; Wang, L.; Thomas, Y.; McMorrow, G.; Denzer, A. Energy efficient operation and modeling for greenhouses: A literature review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 117, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chow, D.; Fang, Y. Methodologies of control strategies for improving energy efficiency in agricultural greenhouses. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 274, 122695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C.; Piromalis, D.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Bartzanas, T.; Loukatos, D. Applications of IoT for optimized greenhouse environment and resources management. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 198, 106993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chow, D. Towards automated greenhouse: A state of the art review on greenhouse monitoring methods and technologies based on internet of things. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 191, 106558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C.; Karavas, C.S.; Loukatos, D.; Bartzanas, T.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Symeonaki, E. Agricultural Greenhouses: Resource Management Technologies and Perspectives for Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2023, 13, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, H.M.; Dubeux, J.C.; Silveira, M.L.; Lira, M.A.; Cardoso, A.S.; Vendramini, J.M. Greenhouse gas mitigation and carbon sequestration potential in humid grassland ecosystems in Brazil: A review. Journal of Environmental Management 2022, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakare, M.S.; Abdulkarim, A.; Zeeshan, M.; Shuaibu, A.N. A comprehensive overview on demand side energy management towards smart grids: challenges, solutions, and future direction. Energy Informatics 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, P.; Vale, Z. Demand Response in Smart Grids. Energies 2023, 16, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, M.H.; Ghadi, M.J.; Ghavidel, S.; Li, L. Demand Response Modeling in Microgrid Operation: a Review and Application for Incentive-Based and Time-Based Programs. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 94, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadinejad, A.; Tomsovic, K. Optimal use of incentive and price based demand response to reduce costs and price volatility. Electric Power Systems Research 2017, 144, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraija, A.; Henao, N.; Agbossou, K.; Kelouwani, S.; Fournier, M.; Nagarsheth, S.H. Deep reinforcement learning based dynamic pricing for demand response considering market and supply constraints. Smart Energy 2024, 14, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Shahryari, E.; Moradzadeh, M.; Siano, P. A survey on microgrid energy management considering flexible energy sources. Energies 2019, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, J.A.; Agbossou, K.; Henao, N.; Nagarsheth, S.H.; Campillo, J.; Rueda, L. Distributed stochastic energy coordination for residential prosumers: Framework and implementation. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2024, 38, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahid-Ghavidel, M.; Sadegh Javadi, M.; Gough, M.; Santos, S.F.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Catalão, J.P. Demand response programs in multi-energy systems: A review. Energies 2020, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallonetto, F.; De Rosa, M.; D’Ettorre, F.; Finn, D.P. On the assessment and control optimisation of demand response programs in residential buildings. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 127, 109861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, E.; Dagdougui, H.; Ojand, K. Hierarchical Distributed Energy Management Framework for Multiple Greenhouses Considering Demand Response. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2023, 14, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etedadi Aliabadi, F.; Agbossou, K.; Kelouwani, S.; Henao, N.; Hosseini, S.S. Coordination of smart home energy management systems in neighborhood areas: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36417–36443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Liu, X.; Wu, C.; Tang, Y. Game-theoretic energy management with storage capacity optimization in the smart grids. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2018, 6, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Javaid, N.; Rasheed, M.B.; Haseeb, A.; Alhussein, M.; Aurangzeb, K. Game theoretical energy management with storage capacity optimization and Photo-Voltaic Cell generated power forecasting in Micro Grid. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2019, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; Decardi-Nelson, B.; You, F. Energy management for demand response in networked greenhouses with multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Applied Energy 2024, 355, 122349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yu, J.; Ren, Y. Demand side management of energy consumption in a photovoltaic integrated greenhouse. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2022, 134, 107433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio, J.S.; Vuelvas, J.; Patino, D.; Correa-Flórez, C.A. Flower Greenhouse Energy Management to Offer Local Flexibility Markets. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouammi, A. Model predictive control for optimal energy management of connected cluster of microgrids with net zero energy multi-greenhouses. Energy 2021, 234, 121274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouammi, A.; Achour, Y.; Zejli, D.; Dagdougui, H. Supervisory Model Predictive Control for Optimal Energy Management of Networked Smart Greenhouses Integrated Microgrid. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2020, 17, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.; Ma, Z.; Demazeau, Y.; Jorgensen, B.N. Agent-based Modeling of Climate and Electricity Market Impact on Commercial Greenhouse Growers’ Demand Response Adoption. Proceedings - 2020 RIVF International Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies, RIVF 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Choi, I.S.; Im, Y.H.; Kim, H.M. Optimal operation of greenhouses in microgrids perspective. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2019, 10, 3474–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.S.; Hussain, A.; Bui, V.H.; Kim, H.M. A multi-agent system-based approach for optimal operation of building microgrids with rooftop greenhouse. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, A.; Maersk-Moeller, H.M.; Corfixen Soerensen, J.; Joergensen, B.N.; Kjaer, K.H.; Ottosen, C.O. Integrating Commercial Greenhouses in the Smart Grid with Demand Response based Control of Supplemental Lighting 2015. [CrossRef]

- Bozchalui, M.C.; Cañizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K. Optimal energy management of greenhouses in smart grids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2015, 6, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediwaththe, C.P.; Stephens, E.R.; Smith, D.B.; Mahanti, A. A Dynamic Game for Electricity Load Management in Neighborhood Area Networks. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 7, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Liu, X.; Tang, D. Game-Theoretic Applications for Decision-Making Behavior on the Energy Demand Side: a Systematic Review. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems 2024, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, T.; Han, W.; Chen, Z. A comprehensive review of research works based on evolutionary game theory for sustainable energy development. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 114–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Tong, H.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, X.; Huang, W. Application of Game Theory in Integrated Energy System Systems: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 93380–93397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersani, C.; Ruggiero, C.; Sacile, R.; Soussi, A.; Zero, E. Internet of Things Approaches for Monitoring and Control of Smart Greenhouses in Industry 4.0. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Escobar, J.J.; Morales Matamoros, O.; Tejeida Padilla, R.; Lina Reyes, I.; Quintana Espinosa, H. A Comprehensive Review on Smart Grids: Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 21, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, J.; Ponce, P.; Molina, A.; Wright, P. Sensing, smart and sustainable technologies for Agri-Food 4.0. Computers in Industry 2019, 108, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelis, L.F.M.; Heuvelink, E. Achieving Sustainable Greenhouse Cultivation, 1st ed.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: London, 2019; p. 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariesen-Verschuur, N.; Verdouw, C.; Tekinerdogan, B. Digital Twins in greenhouse horticulture: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 199, 107183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.A.; Ma, Z.; Veje, C.; Clausen, A.; Aaslyng, J.M.; Jørgensen, B.N. Greenhouse industry 4.0 – digital twin technology for commercial greenhouses. Energy Informatics 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slob, N.; Hurst, W. Digital Twins and Industry 4.0 Technologies for Agricultural Greenhouses. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Veen, A.; Van Leeuwen, C.; Helmholt, K.A. Self-Organization in Cyberphysical Energy Systems: Seven Practical Steps to Agent-Based and Digital Twin-Supported Voltage Control. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2024, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosinsky, C.; Naglic, M.; Lehnhoff, S.; Krebs, R.; Westermann, D. A Fortunate Decision That You Can Trust: Digital Twins as Enablers for the Next Generation of Energy Management Systems and Sophisticated Operator Assistance Systems. IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 2024, 22, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drgoňa, J.; Arroyo, J.; Cupeiro Figueroa, I.; Blum, D.; Arendt, K.; Kim, D.; Ollé, E.P.; Oravec, J.; Wetter, M.; Vrabie, D.L.; et al. All you need to know about model predictive control for buildings. Annual Reviews in Control 2020, 50, 190–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altes-Buch, Q.; Quoilin, S.; Lemort, V. A modeling framework for the integration of electrical and thermal energy systems in greenhouses. Building Simulation 2022, 15, 779–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, J.; Xu, F.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, L. Energy demand forecasting of the greenhouses using nonlinear models based on model optimized prediction method. Neurocomputing 2016, 174, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, F.; Berenguel, M.; Guzmán, J.L.; Ramírez-Arias, A. Modeling and Control of Greenhouse Crop Growth; Vol. 171, 2015; pp. 197–214.

- Gijzen, H.; Heuvelink, E.; Challa, H.; Dayan, E.; Marcelis, L.F.; Cohen, S.; Fuchs, M. Hortisim: A model for greenhouse crops and greenhouse climate, 1998. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, L.; Xia, X. Hierarchical model predictive control of Venlo-type greenhouse climate for improving energy efficiency and reducing operating cost. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 264, 121513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ridder, F.; van Roy, J.; Vanlommel, W.; Van Calenberge, B.; Vliex, M.; De Win, J.; De Schutter, B.; Binnemans, S.; De Pauw, M. Convex parameter estimator for grey-box models, applied to characterise heat flows in greenhouses. Biosystems Engineering 2020, 191, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wei, R.; Xu, L. Energy consumption prediction of a greenhouse and optimization of daily average temperature. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xu, L.; Wei, R.; Zhu, B. Multi-objective control optimization for greenhouse environment using evolutionary algorithms. Sensors 2011, 11, 5792–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mourik, S.; van Beveren, P.J.; López-Cruz, I.L.; van Henten, E.J. Improving climate monitoring in greenhouse cultivation via model based filtering. Biosystems Engineering 2019, 181, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Venugopal, M.; Vasu, R.M.; Roy, D. A Kushner-Stratonovich Monte Carlo filter applied to nonlinear dynamical system identification. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2014, 270, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Incorporating Artificial Intelligence Technology in Smart Greenhouses: Current State of the Art. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altes-Buch, Q.; Quoilin, S.; Lemort, V. Greenhouses: A Modelica Library for the Simulation of Greenhouse Climate and Energy Systems. Proceedings of the 13th International Modelica Conference, Regensburg, Germany, March 4–6, 2019 2019, 157, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalai, S. Raiz-vertical-farms greenhouse simualtor, 2022.

- Frausto, H.U.; Pieters, J.G.; Deltour, J.M. Modelling greenhouse temperature by means of auto regressive models. Biosystems Engineering 2003, 84, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakari, A.; Ghani, S. Regression equation for estimating the maximum cooling load of a greenhouse. Solar Energy 2022, 237, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, T.; Kavga, A.; Thomopoulos, V.; Argiriou, A.A. Neural Network Model for Greenhouse Microclimate Predictions. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Tiwari, K.N. Prediction of greenhouse micro-climate using artificial neural network. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 2017, 15, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharghory, S.M. Deep Network based on Long Short-Term Memory for Time Series Prediction of Microclimate Data inside the Greenhouse. International Journal of Computational Intelligence and Applications 2020, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, Q.; Katzin, D.; Qian, T.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F. Boosting the prediction accuracy of a process-based greenhouse climate-tomato production model by particle filtering and deep learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 211, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-García, J.; Terroso-Sáenz, F.; Cecilia, J.M. A multi-model deep learning approach to address prediction imbalances in smart greenhouses. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2024, 216, 108537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzin, D.; van Mourik, S.; Kempkes, F.; van Henten, E.J. GreenLight – An open source model for greenhouses with supplemental lighting: Evaluation of heat requirements under LED and HPS lamps. Biosystems Engineering 2020, 194, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivo, C.; Mazzeo, D.; Panico, S.; Bonuso, S.; Matera, N.; Congedo, P.M.; Oliveti, G. Complete greenhouse dynamic simulation tool to assess the crop thermal well-being and energy needs. Applied Thermal Engineering 2020, 179, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz-Rodríguez, E.; Kubota, C.; Giacomelli, G.A.; Tignor, M.E.; Wilson, S.B.; McMahon, M. Dynamic modeling and simulation of greenhouse environments under several scenarios: A web-based application. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2010, 70, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Henten, E.J.; Bontsema, J. Time-scale decomposition of an optimal control problem in greenhouse climate management. Control Engineering Practice 2009, 17, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, L.; Xia, X. Model predictive control of a Venlo-type greenhouse system considering electrical energy, water and carbon dioxide consumption. Applied Energy 2021, 298, 117163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcego, B.; Yin, W.; Boersma, S.; van Henten, E.; Puig, V.; Sun, C. Reinforcement Learning versus Model Predictive Control on greenhouse climate control. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2023, 215, 108372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, J.J.; Zarei, G.; Momeni, D.; Faridi, H. Non-linear control model for use in greenhouse climate control systems. Research in Agricultural Engineering 2022, 68, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; You, F. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Automatic Control in Semi-Closed Greenhouse Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, N.; Duplaix, J.; Enéa, G.; Haloua, M.; Youlal, H. Greenhouse climate modelling and robust control. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2008, 61, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beveren, P.J.; Bontsema, J.; van Straten, G.; van Henten, E.J. Optimal control of greenhouse climate using minimal energy and grower defined bounds. Applied Energy 2015, 159, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; You, F. Smart greenhouse control under harsh climate conditions based on data-driven robust model predictive control with principal component analysis and kernel density estimation. Journal of Process Control 2021, 107, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Method | Objective | Pricing | Renewable Energy Integration |

Max. Demand Limit |

Mathematical Model | Unc. | Reliability/Scalability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | WT | HVAC | TESS | PV | BESS | WP | AL | Crop | |||||||

| [46] | Multi-agent DRL | Load reduction | Dynamic pricing | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | It can be adapted to include other renewable sources, such as wind and geothermal energy |

| [42] | ADMM-based MPC for multi greenhouse system |

Aggregator water reservoir pumping system |

Dynamic pricing | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | Applicable for multi greenhouse system, limited to the use of water reservoir |

| [47] | Prosumer-based PSO problem-solving |

Maximises power income and time-shifting power usage |

Day-ahead dynamic pricing (peak and valley) |

✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | Limited to prosumer-based models |

| [48] | Bi-level MILP Stackelberg game-theory |

Minimise HVAC consumption | Hourly load curve-based pricing |

- | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20% HVAC flexibility demonstrated, which can be extended to stochastic formulations |

| [49] | Coordinated optimization embedded MPC |

Optimal dispatch of renewables, water storage and HVAC |

- | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | Balanced use of renewables and power loads |

| [50] | Supervisory Centralized MPC |

Operating setpoints of microclimate |

- | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | Applicable to Smart Multi-floor Vertical Greenhouses |

| [51] | Agent-based implicit DR | Optimal overall consumption | Time-varying spot market pricing |

- | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | Commercial software dependencies |

| [52] | Robust optimization (grid-connected and islanded mode) |

Balancing power buying and selling to grid |

Time-of-Use (ToU) market pricing |

✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | Applicable for trading in different operational modes |

| [53] | Multi-agent system with modified contract protocol |

Minimizing operational cost of building microgrid (energy transactions with grid) |

ToU day-ahead market pricing |

✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | Applicable to rooftop type greenhouses |

| [54] | Time-based DR | Optimal energy consumption of artificial lighting |

spot market pricing |

- | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | Commercial software dependencies, limited modeling ability |

| [55] | Monte Carlo Simulation and MILP |

Minimizing total energy cost and demand charges |

Real-time pricing + demand charges + flat rate price |

- | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | Applicable to hierarchical control approach for greenhouses |

| Category | Variable | Drip Irrigation | Sprinkler Irrigation | Hydroponics | Crop Growth | External Weather |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Control | Temperature | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Humidity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| CO2 concentration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | |

| Light intensity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Soil Parameters | Soil moisture | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Soil temperature | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | |

| Soil pH | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | |

| Soil salinity | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | |

| Water Quality | Water pH | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - |

| Water salinity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | |

| Water temperature | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | |

| Plant Growth | Plant height | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Leaf area index | - | - | - | ✓ | - | |

| Chlorophyll content | - | - | - | ✓ | - | |

| Biomass | - | - | - | ✓ | - | |

| Hydroponics | Nutrient concentration | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| pH level | - | - | ✓ | - | - | |

| Dissolved oxygen | - | - | ✓ | - | - | |

| External Weather | Ambient temperature | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Wind speed | - | - | - | - | ✓ | |

| Rainfall | - | - | - | - | ✓ | |

| Solar radiation | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| References | Platform | Method | Open Source |

Modular Design |

Microclimate Model |

Crop Model |

Crops Grown |

Supplementary Lighting |

Validated / Location |

Sub-Systems Measurements |

Data Acquisition |

Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [81] | Modelica | Sub-process oriented |

✓ (3-clause BSD License) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Tomato | ✓ | ✓ (Beglium) | HVAC, Window Aperture, Lighting, Energy Consumption |

✓ | ✓ (PID) |

| [90] | MATLAB + EnergyPlus |

ODEs | ✗ (Apache 2.0) | ✗ | ✓ | Yes, Detailed Crop Model |

Tomato |

✓ (Configurable HPS/LED) |

✓ (Netherlands and USA) |

Microclimate, Lighting, Energy Consumption |

✓ | ✗ |

| [91] | Sketchup + TRNSYS |

CFD | 55 |

✓ (Requires new 3D design) |

✓ (20 Thermal Zones) |

✓ | Flowering Crops |

✓ (HPS) | ✓ (Italy) | Crop Thermal Condition, Energy Consumption |

✓ (Hourly) | ✗ |

| [73] | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | ✗ |

✓ (Semi-closed and Closed) |

✓ | ✓ | Multiple vegetables and fruits |

✓ |

✓ (Weather File Required) |

HVAC, Lighting, Energy Consumption |

✓ (Hourly) | ✓ |

| [82] | Python | ODEs | ✓ | ✗ (Changeable characteristics of the structure) |

✓ | ✓ | Basil, Tomato | ✓ (LEDs) | ✓ (Spain) | Microclimate, Ventilation, CO2, Humidity, Lighting, Energy Consumption |

✓ (Custom) | ✓ (only P) |

| [92] | Web-based Application, ActionScript 2.0 |

Energy and Mass Balance |

✗ |

✓ (Three different structure) |

✓ |

✓ (Plant Transpiration) |

Tomato | ✗ | ✓ (Arizona, USA) | Microclimate |

✓ (15 min time step) |

✓ (ON/OFF) |

| Reference | Control Framework |

Optimization Algorithm |

Linear/ Nonlinear |

Controlled Variables |

Maniplulated Variables |

Disturbance Variables |

Objective | Convergence / Stability |

Sensitivity | Results of the study | Platform | Climate | Crop | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | EC | |||||||||||||

| [17] | NMPC | IPOPT | N | T, H, , AL | Fan flow rate, heating, injection, fogging rate, shade curtain coverage |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Min. control cost CO2, Nat. Gas and Elec. |

Jacobian linearization for stability |

On penalty weights and energy costs |

A 20% reduction in control costs and 40% increase in nominal\ sensitivity analysis |

do-MPC / Python |

Winter, Spring, Summer |

Tomato | |

| [93] | Two-stage optimal PI control |

Maximum Principle of Pontryagin |

L | CDW, T, H, | Ventilation, heating, injection |

Ext. T, H, SR, , WS |

Max. the diff. B/W gross income and operating cost |

Necessary conditions to achieve optimality |

N/A | Cascade control loop with slower crop growth and faster microclimate dynamics |

N/A | Winter | Lettuce | |

| [77] | MIMO PID | Multi-objective EA | L | T, H | Ventilation, fogging rate |

Ext. T, H, SR, , WS |

Static-dynamic ref. tracking |

ISE convergence | N/A | Time-consuming method not suitable for real-time control requirement |

MATLAB | N/A | ||

| [96] | Nonlinear control |

N/A | N | T, H | Heating, fogging rate |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Ref. tracking with fixed rules |

N/A | N/A | Improved transient time response in comparison to SMC |

MATLAB | Summer | N/A | |

| [94] | MPC - two layer strategy |

IPOPT | N | T, H, | Heating/cooling, ventilation, injection, solar radiation-based shading rate |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Min. energy, water and consumption |

N/A | Energy, water and costs |

Cannot work in sub-zero exterior climates, 67% of total cost reduction |

MATLAB | Winter (above 10C) |

N/A | |

| [95] | Receding Horizon MPC |

IPOPT | N | CDW, T, H, | Heating/cooling, ventilation, injection |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Max. crop yield Min. energy |

N/A | N/A | MPC achieves a higher economic return but slow due to an opt. problem |

CasADi + MATLAB |

Winter (2 to 8.5 C ) |

Lettuce | |

| RL agent based control |

DDPG | N | CDW, T, H, | Heating/cooling, ventilation, injection |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Max. crop yield Min. energy |

500 epochs agent training, each epoch is one day of crop growth |

White noise data to avoid overfitting |

RL is faster after learning but permissive with humidity constraints. A health problem for the crops |

N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| [97] | DRL agent based control |

-greedy strategy with SGA for max. Q-learning |

N | T | Heating power | Ext. T | Maintaining T | N/A | Stochastic transient dyanmics |

61% more energy savings in Q-learning than DDPG |

MATLAB | Winter, Spring |

Tomato | |

| [16] | AI-based model-free control |

Robust Opt. with L-BFGS/ Adam |

N | T, H, , Carbohydrates per unit area in fruit, leaves and stem |

Heating/cooling, humidification, injection, AL |

Ext. T, RH, SR, , ST |

Max. comfort | Improve energy efficiency |

N/A | Weather unc. | 26.8% improvement in ref. tracking and 57% in energy consumption over traditional MPC |

MATLAB | Winter | Tomato |

| [98] | Multivariate Robust control |

LMI formalism | L | T, H | Heating, Moistening, Roofing, Shadiness |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Min. norm | Check of robust stability performed |

Model unc. | 12% and 33 % improvement in the ref. tracking for T and H |

MATLAB | Spring | N/A | |

| [99] | Optimal control |

PROPT algorithm | N | T, H, | Heating/cooling, ventilation, injection |

Ext. T, H, SR, , WS |

Min. energy | N/A | N/A | Heating and cooling energy were potentially reduced by 47% and 15% |

MATLAB | Year around | Tomato, Cucumber, Sweet Pepper and Rose |

|

| [100] | Robust MPC | ADF policy | L | T, H, | Heating/cooling, dehumidifcation, injection |

Ext. T, H, SR, |

Min. power of actuators and constraint violation penalty |

Bounded I/Os and COV for stability |

Weather unc. | PCA and KDE-based data-driven robust MPC needs lower total control cost than rule-based control |

MATLAB | Summer | Tomato | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).