Submitted:

09 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of the Motivational Interviewing Matrix on reducing anger and increasing self-efficacy in male high school students. Method: This quasi-experimental study employed a pre-test-post-test control group design. The study sample consisted of 8 male 10th and 11th grade students, selected through convenience sampling and randomly assigned to two groups: experimental (n=4) and control (n=4). Participants were assessed using the Spielberger State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2) and the Morris Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (2001). The experimental group received 8 counseling sessions based on the Motivational Interviewing Matrix model, while the control group received no intervention. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, paired samples t-test, and independent samples t-test. Results: The results indicated that the Motivational Interviewing Matrix significantly reduced anger and increased self-efficacy in the experimental group. The mean anger score in the experimental group decreased from 32.25 to 23.75, while no significant change was observed in the control group (31.50 in the pre-test to 30.75 in the post-test). Additionally, the mean self-efficacy score in the experimental group increased from 14.50 to 21.00, while the control group showed a slight change (14.25 in the pre-test to 14.75 in the post-test). The paired samples t-test revealed that these changes were significant in the experimental group (t anger = 6.28, P = 0.002; t self-efficacy = 7.11, p = 0.001). Furthermore, the independent samples t-test showed a significant difference between the experimental and control groups (t anger = 3.96, p = 0.004; t self-efficacy = 4.55, p = 0.002). The effect size also indicated a strong and sustained impact of the intervention on the study variables (d anger = 2.10, d self-efficacy = 2.40). Conclusion: The findings of this study suggest that the Motivational Interviewing Matrix can be used as an effective tool in improving emotional regulation and enhancing self-efficacy in students. It is recommended that this model be implemented in school counseling and emotional management training programs.

Keywords:

Introduction

Background

Significance of the Study

- ○

- It examines a novel and structured method for managing emotions and improving academic performance.

- ○

- It addresses the practical and case-based implementation of this intervention in an educational setting.

- ○

- It can be used as an operational model for school counselors.

Literature Review

Research Objectives

-

General Objective;

- ○

- To investigate the effect of the Motivational Interviewing Matrix on reducing anger and increasing self-efficacy in male high school students.

-

Specific Objectives;

- ○

- To examine the effect of the Motivational Interviewing Matrix on reducing the intensity of anger in students.

- ○

- To examine the effect of this intervention on increasing the ability to control anger and manage emotions.

- ○

- To evaluate the effect of this model on increasing academic self-efficacy and confidence.

- ○

- To examine changes in students’ behavioral and cognitive patterns after the intervention.

Research Hypotheses

Methodology

-

The present study is a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test-post-test control group design. In this design, 8 male students with high scores on the Spielberger State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (1988) and low scores on the Morris Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (2001) were selected as research participants and randomly assigned to two groups: experimental and control (4 in each group).

- ○

- Experimental Group: Received 4 counseling sessions using the Motivational Interviewing Matrix.

- ○

- Control Group: Received no intervention and only participated in the pre-test and post-test.

- ○

- After the sessions, both groups were re-tested for anger and self-efficacy to examine the effect of the intervention.

Population

- The statistical population of this study includes male 10th and 11th grade students of Shahed Imam Hossein High School in the academic year 2024-2025, who were referred to the school counselor and had symptoms of high anger and low self-efficacy.

Sample and Sampling Method

-

Sampling Method;

- ○

- The research sample was selected using convenience sampling from students who were referred to the school counseling office.

-

Sample Selection Criteria;

- ○

-

Inclusion Criteria;

- ▪

- High score on the Spielberger State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI-2).

- ▪

- Low score on the Morris Academic Self-Efficacy Scale.

- ▪

- No similar interventions received in the past 6 months.

- ▪

- Consent of the student and parents to participate in the study.

- ○

-

Exclusion Criteria;

- ▪

- Absence from more than 2 counseling sessions.

- ▪

- Simultaneous receipt of other psychological therapies.

-

Group Assignment;

- ○

- After the final selection, 8 students were randomly assigned to two groups: experimental and control (4 in each group). A pre-test was conducted for both groups, then the experimental group received the intervention and the control group remained without intervention. At the end, a post-test was conducted in both groups.

Research Instruments

Spielberger State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2)

- ○

-

The first section has 15 items and includes the State Anger scale and its subscales, with the following items:

- ▪

- a) Feeling Angry: 1, 2, 3, 6, 10

- ▪

- b) Verbal Expression of Anger: 4, 9, 12, 13, 15

- ▪

- c) Physical Expression of Anger: 5, 7, 8, 11, 14

- ○

-

The second section has 10 items and includes the Trait Anger scale, which has two subscales derived from the following items:

- ▪

- a) Angry Temperament: 16, 17, 18, 21

- ▪

- b) Angry Reaction: 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25

- ○

-

The third section has 32 items and includes the Anger Expression and Control scale, which has four scales composed of the following items:

- ▪

- a) Outward Anger Expression: 27, 31, 35, 39, 43, 47, 51, 55

- ▪

- b) Inward Anger Expression: 29, 33, 37, 41, 45, 49, 53, 57

- ▪

- c) Outward Anger Control: 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, 46, 50, 54

- ▪

- d) Inward Anger Control: 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 56

Morris Academic Self-Efficacy Scale (2001)

- ○

- Items 1, 5, 7, 10, 13, 16, 18 relate to social self-efficacy.

- ○

- Items 2, 3, 4, 8, 11, 14, 19, 21 relate to emotional self-efficacy.

- ○

- Items 6, 9, 12, 15, 17, 20 relate to academic self-efficacy.

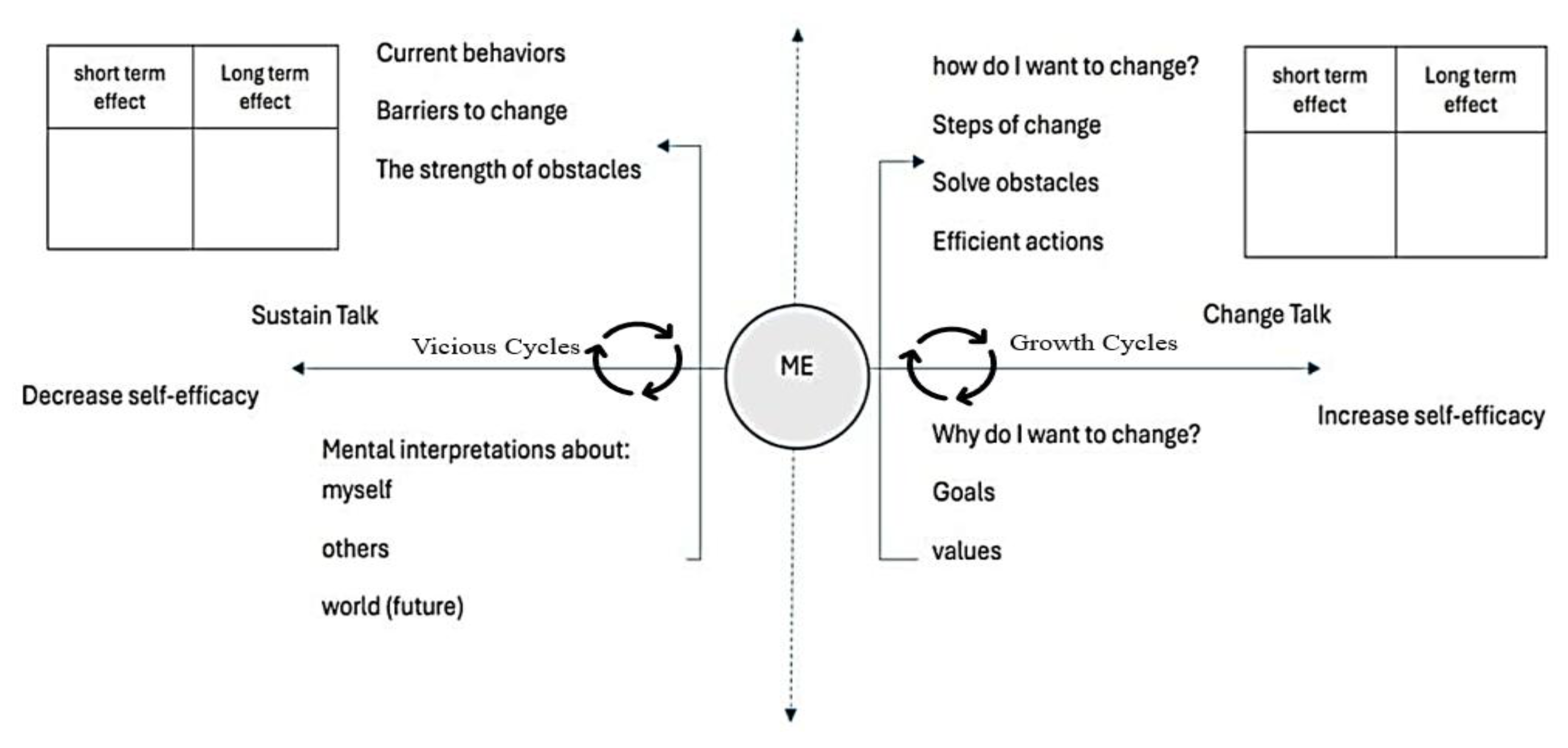

Motivational Interviewing Matrix Tool

Data Analysis Methods

Descriptive Statistics

- Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum scores of anger and self-efficacy in the pre-test and post-test.

Test of Normality

-

Before conducting statistical tests, the normal distribution of the data was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test:

- ○

- If the data were normally distributed: Parametric tests of independent t-test and paired t-test were used.

- ○

- If the data were not normally distributed: Non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U and Wilcoxon signed-rank test) were used.

Paired t-Test

- To examine the effect of the intervention in the experimental group, the pre-test and post-test scores of the experimental group were compared using the paired t-test.

Independent t-Test

- To compare the post-test scores of the two groups, experimental and control, the independent t-test was used. This test indicates whether the difference between the two groups is significant or not.

Effect Size Analysis

- To determine the magnitude of the intervention effect, the effect size was calculated.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

- To examine the effect of the Motivational Interviewing Matrix on reducing anger and increasing self-efficacy in students, the mean and standard deviation of pre-test and post-test scores were calculated for both the experimental and control groups. Table 1 shows the results of the descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Group | Pre-test Mean | Pre-test SD | Post-test Mean | Post-test SD |

| Anger | Experimental | 32.25 | 2.64 | 23.75 | 2.05 |

| Control | 31.50 | 2.90 | 30.75 | 2.87 | |

| Self-Efficacy | Experimental | 14.50 | 2.07 | 21.00 | 1.82 |

| Control | 14.25 | 2.38 | 14.75 | 2.40 |

-

The results of Table 1 indicate that:

- ○

- The mean anger score in the experimental group significantly decreased after the intervention, while no significant change was observed in the control group.

- ○

- The mean self-efficacy score in the experimental group increased, but remained almost constant in the control group.

Test of Normality

- To determine whether the data distribution is normal, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used. The results are presented in Table 2.

- Since the significance level is greater than 0.05 in all cases, it can be concluded that the data have a normal distribution. Therefore, parametric t-tests (independent and paired) were used for data analysis.

Paired t-Test for the Experimental Group

- To examine the changes in anger and self-efficacy scores within the experimental group, the paired t-test was used. The results are presented in Table 3.

| Variable | Mean Difference | t | Significance Level (Sig.) |

| Anger | 8.50 | 6.28 | 0.002** |

| Self-Efficacy | 6.50 | 7.11 | 0.001** |

-

The results of Table 3 show that:

- ○

- The significance level for both variables is less than 0.05, so the decrease in anger and the increase in self-efficacy in the experimental group are significant.

- ○

- The effect of the intervention on increasing self-efficacy (t = 7.11) was stronger than the effect on reducing anger (t = 6.28).

Independent t-test for Comparing Experimental and Control Groups

- To examine the post-test difference between the experimental and control groups, the independent t-test was used. The results are presented in Table 4.

| Variable | Mean (Experimental) | Mean (Control) | t | Significance Level (Sig.) |

| Anger | 23.75 | 30.75 | 3.96 | 0.004** |

| Self-Efficacy | 21.00 | 14.75 | 4.55 | 0.002** |

-

The results of Table 4 show that:

- ○

- The significance level for both variables is less than 0.05, so the difference between the experimental and control groups is statistically significant.

- ○

- Students who participated in the Motivational Interviewing Matrix sessions showed lower anger and higher self-efficacy.

Intervention Effect Size

- Cohen’s d effect size was used to determine the magnitude of the intervention effect.

| Variable | Effect Size (d) |

| Anger | 2.10 |

| Self-Efficacy | 2.40 |

- An effect size greater than 0.8 indicates a strong intervention effect. Therefore, the Motivational Interviewing Matrix had a very high impact on reducing anger and increasing self-efficacy.

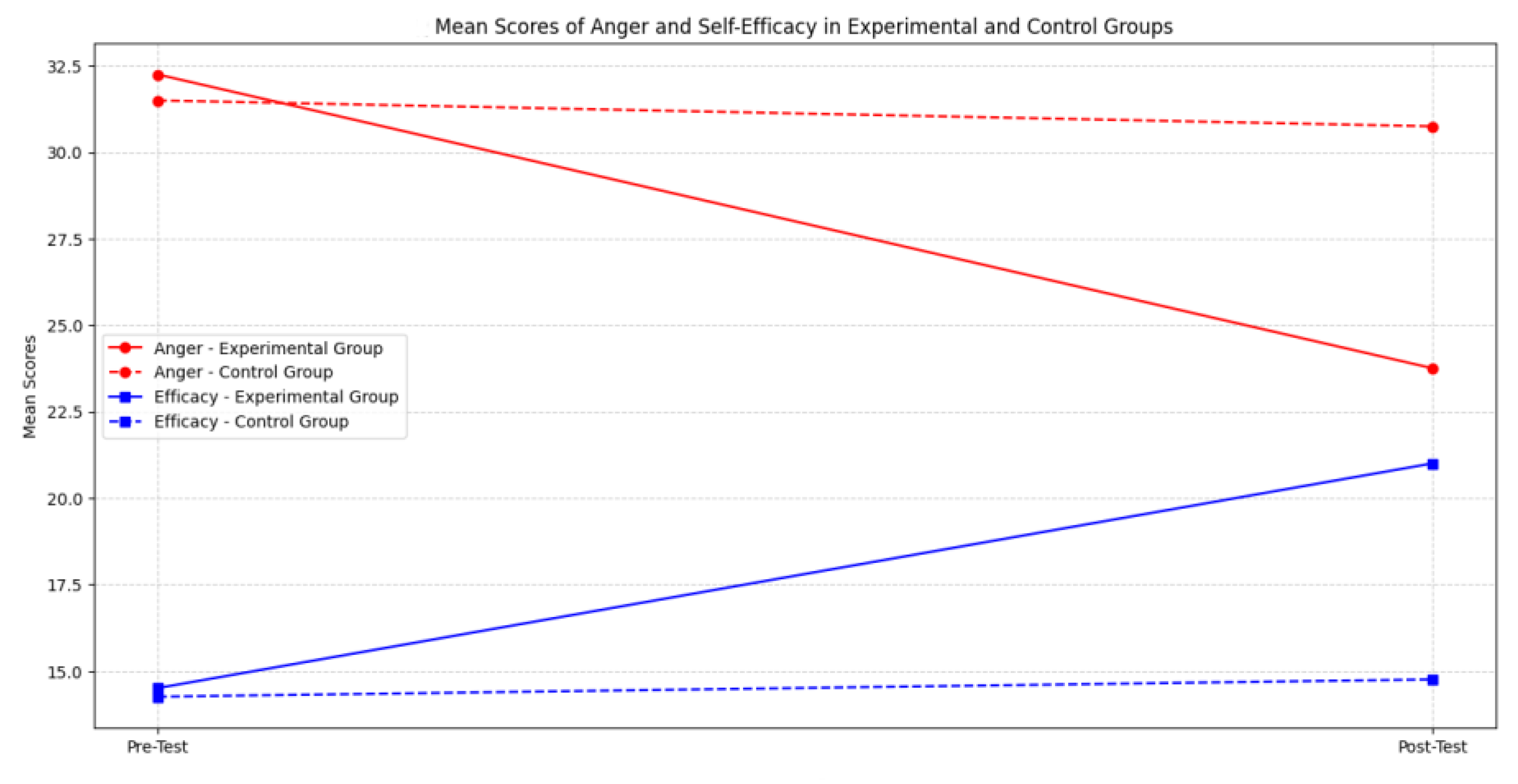

Graph of Pre-Test and Post-Test Score Changes

Graph Analysis

- ○

- Solid Red Line: Decrease in anger scores in the experimental group after the intervention.

- ○

- Dashed Red Line: Negligible change in anger scores in the control group.

- ○

- Solid Blue Line: Increase in self-efficacy scores in the experimental group after the intervention.

- ○

- Dashed Blue Line: Negligible change in self-efficacy scores in the control group.

Summary of Findings

- The overall results of the study show that;

- Conclusion: The Motivational Interviewing Matrix can be used as an effective method to reduce anger and increase self-efficacy in high school students.

Discussion and Conclusions

Discussion

- The Motivational Interviewing Matrix, due to the combination of ACT and motivational interviewing principles, not only helped reduce anger and increase self-efficacy, but also enabled students to find more motivation for sustainable changes by recognizing their values and goals. This model, using a four-part structure, allowed counselors to simultaneously address students’ behavioral barriers and deep beliefs and prevent the creation of vicious behavioral cycles. The findings of this study showed that the use of this model can be used as a practical and innovative tool in school counseling.

- The results of this study showed that the Motivational Interviewing Matrix has a significant effect on reducing anger and increasing self-efficacy in male high school students. The findings indicated that the experimental group, after the intervention, had a significant decrease in anger scores and a significant increase in self-efficacy scores, while the control group did not experience a significant change. These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the Motivational Interviewing Matrix in managing negative emotions and enhancing students’ individual abilities.

- The results of the present study are consistent with previous studies. For example, Rollnick and Miller’s (2013) research, which showed that motivational interviewing can be effective in reducing negative emotions and promoting intrinsic motivation, is consistent with the findings of this study. In addition, Karimi et al.’s (2021) research in Iran showed that motivational interviewing-based interventions can improve students’ self-efficacy levels, which is fully consistent with the findings of the present study. However, some studies have reported a more limited effect for this intervention; for example, Jin et al. (2019) showed that motivational interviewing will have a lasting effect if follow-up sessions are also conducted after the intervention. Therefore, it can be concluded that the long-term effectiveness of this approach requires continuous follow-ups.

Conclusions and Recommendations

- ○

- Based on the research findings, the Motivational Interviewing Matrix can be used as an effective method to reduce anger and increase students’ self-efficacy in educational settings. This method not only helps students gain a better understanding of their inner feelings and motivations, but also provides practical pathways for managing emotions and improving academic performance.

- ○

- Limitations: One limitation of this study was the small sample size (n=8), which may affect the generalizability of the results. Also, the present study lacked long-term follow-ups, and the sustainability of the Motivational Interviewing Matrix effects over time cannot be stated with certainty. To address these limitations, it is recommended that future research be conducted with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods.

Research and Practical Recommendations

- ○

- To ensure the sustainability of changes, it is recommended that follow-up sessions be conducted after the intervention, as some studies have shown that behavioral changes are more lasting when sessions are continued.

- ○

- It is also recommended to implement this model in other age groups and among female students to examine its generalizability across different populations.

- ○

- Comparing the effectiveness of this method with other counseling approaches (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy) can be conducted in future research to determine how much more effective the Motivational Interviewing Matrix is compared to other interventions.

- ○

- School administrators and counselors can use this model in individual or group counseling sessions for students who are facing emotional and academic problems.

Overall Conclusions

- ○

- The findings of this study showed that the Motivational Interviewing Matrix can be used as an effective and practical tool to improve emotional regulation and increase self-efficacy in high school students. Given the positive results of this research, the use of this model in educational and counseling settings is recommended.

References

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual review of psychology, 53(1), 27-51. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman.

- Delshad, S. (2024). From Challenge to Change: The Art of Motivational Interviewing in Schools. Bojnord: Dor Ghalam Publications.

- Jin, H., et al. (2019). The effect of motivational approaches on self-efficacy and academic stress among high school students. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 10(2), 123-140.

- Karimi, M., et al. (2021). Investigating the Effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on Anger Management and Increased Self-Efficacy in Iranian Students. Iranian Journal of Educational Psychology, 17(1), 45-62.

- Polk, K., Schoendorff, B., Webster, M., & Olaz, F. (2016). A Step-by-Step Guide to Using the Matrix in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. S. Delshad et al. (2024). Bojnord: Dor Ghalam Publications.

- Rollnick, S., Arkowitz, H., & Miller, W. R. (2023). Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. M. Ahovan & M. Delroba. Tehran: Arjmand Publications.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68..

- Schöen, R. R., Braet, C., & Bosmans, G. (2015). A treatment for comorbid anxiety and oppositional defiant problems in children: a pilot study. Child & family behavior therapy, 37(2), 115-133..

- Spielberger, C. D. (1988). Manual for the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

| Variable | Group | Shapiro-Wilk Statistic | Significance Level (Sig.) |

| Anger (Pre-test) | Experimental | 0.945 | 0.452 |

| Anger (Post-test) | Experimental | 0.958 | 0.521 |

| Self-Efficacy (Pre-test) | Experimental | 0.963 | 0.537 |

| Self-Efficacy (Post-test) | Experimental | 0.941 | 0.428 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).