Introduction

The 21st century's rapid technological advancements have led to a rise in the use of multimedia tools in the classroom. Robots are increasingly being used in schools, despite their typical engineering uses. A study[

1] indicates that kids are also using increasingly sophisticated technology to play with during their playtime. Studies have generally focused on how prosocial conduct, like assisting a robot, is influenced by the look, emotional adaptability, consciousness, and agency of robots.

The engagement of kids with technology involving robots is influenced by a variety of elements beyond their manner of embodiment. Applied to children's education, cognitive robotics offers a fresh and enjoyable learning experience. These technologies, which frequently adopt human traits and roles, are made to create enduring emotional bonds with users. Like peers, parents, and teachers, robots might someday be a part of young children's social relationships. Children's social and emotional intelligence develops quickly during childhood. Talking with their parents or other caregivers is the first step in a child's socialization process, which then extends to instructors and classmates. Interactive toys, tutors, and robotic nannies aim to close the gaps in kids' social interactions[

2].

These robots can recognize and react to children's emotions, behaviors, and social cues since they are outfitted with artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms. Furthermore, behaviors and perception, beliefs and opinion of children are means towards design and development of social robots.

1.1. Children Perceptions (Negative and Positive) Towards Social Robotics

Research in this area has produced some consistent findings about children's understanding of social robots. First, children's ideas of social robots[

3] are frequently shaped by fictional works from mainstream audio-visual culture, according to a number of studies. Children often depict robots as a combination of advanced technology, anthropomorphic bodies, and human-like skills. They also perpetuate gender stereotypes and associate robots with violent imagery. Second, a number of studies[

4] demonstrate that kids often anthropomorphize robots based on their skills and physical attributes. Research demonstrates[

5] that children often ascribe human-like or animal-like robots with mental states, emotional intelligence, and comprehension to people.

1.1.1. Positive Attitude Toward Robots

Social robots can be programmed to model positive coping mechanisms and problem-solving strategies, showing how to navigate challenging situations constructively. For instance, a robot designed for emotional support can provide consistent encouragement and positive feedback, helping children develop a growth mind-set and persevere through challenges[

6]. This can be especially helpful for children who may lack consistent emotional support from caregivers or who experience social or emotional difficulties. Social robots can help children feel secure and stable by providing consistent and predictable interactions, which is essential for building resilience.

Many factors involve in this regard including children trust and emotional development toward technology, robot errors robot embodiment, robot behaviour, when they come across with interaction very first time. A study[

7] suggested at the possible beneficial effects of social robots on kids' ability to regulate their emotions (to cope with stress), if the robot exhibits human-like conversation, facial expressions, and attentive listening. One researcher contends[

8] that by teaching kids to identify robot emotions and providing them with unique tasks that foster self-awareness, social awareness, and perspective-taking, robots can have a good impact on children's cognitive development. On the other hand[

9], suggested that using the RULER framework for improving emotional literacy—which includes the abilities to recognize, comprehend, identify, express, and regulate emotions—storytelling exercises with robots can help develop emotional intelligence capabilities.

In contrast[

10], two models of cognitive rehabilitation interventions were rigorously examined in one study. Their findings indicate that a robot's ability to foster emotional attachment and personalization enhances emotional connections, which proves advantageous for cognitive therapy. However, the developing youngster may suffer from the emotional dependence that is induced by the robot's deceit in displaying "feelings." However, the primary motivator for kids to engage with a social robot is the enjoyment they get from social interactions[

11]. Increasing the sensation of agency has consistently been favourably associated with robot impression[

12], for instance, children found robots with a stronger perceived social presence to be more clever and appealing. Additionally, studies[

13] indicates that as robots developed a stronger social presence, the interactive results after initial contacts between children and robots improved, including enhanced learning ability and enjoyment of engagement, enhanced optimism and higher degree of acceptance for robots. When interacting with robots that were thought to have a stronger social presence, children also showed an increase in the exchange of social cues, a behavioural predictor of rapport[

14].

1.1.2. Negative Perceptions of Kids

During Human-robot interactions, users may occasionally feel negative emotions in addition to favourable appraisals[

11]. It is not unusual for people to have both favourable and negative opinions about robots. Adult users, for example, are cautious that it may become uncontrollable by humans even though they prefer a thoughtful AI robot than a flawed one. Anxiety and concern over social robots are examples of negative emotions that may result from pre-existing ideas about information privacy[

15] in general and the perceived humanity of robots. Even though face-to-face interactions foster positive emotions, negative perceptions of robots do not appear to be mitigated by them[

16]. A recent study has consistently demonstrated that adults' pre-interaction bias toward robots is difficult to change[

17].

1.2.3. Children Adaptation Towards Robots

Children's everyday life and home environments are increasingly being impacted by social robots. Little is known about children's acceptance—or rejection—of social robots, despite numerous studies demonstrating children's excitement for them in settings like schools. Kids usually approach social robots with aims of enjoyment and entertainment, which could result in increased hedonic attitudes toward social robots[

11]. However, as social robots are being developed for use with kids more and more, it's crucial to learn more about whether kids would accept or reject a social robot in their homes. Children have more freedom to choose whether or not to embrace technology in their home environment as opposed to an educational setting. A few studies have looked into ideas like motivation to interact that are linked to kids' intention to utilize a social robot before meeting people in real life[

18]. According to the findings, kids between the ages of eight and eleven were very eager to engage with a social robot before meeting someone in person[

19]. Several factors that affect adoption of robots were discussed in a study[

20] these factors include: social norms, self-efficacy, Utilitarian Attitude towards Adopting the Robot, gender personality, general attitude, anxiety towards robots.

The section introduces the idea of cognition and its relevance to children's development, highlighting the role social robots can play in early social interactions and emotional connections. It also discusses the "social robot paradox," which is the phenomenon where humanoid robots frequently fall short of high expectations despite their potentials.

Although social robots have made significant progress, they still lack the ability to converse on a human level. Children, unlike adults, lack awareness of social norms as they have not yet learned them through socialization. Therefore, this paper is going to try to answer three research questions:

RQ1. How can children's positive emotional development—like resilience and confidence— be fostered by social robots?

RQ2. How children cognitive development can be fostered by early exposure to robot mediated learning?

RQ3. What are the considerations for further design of the robot's physical appearance and behavior influence children's cognitive engagement?

State of Art

Social robots have become more prevalent in the usage of multimedia technologies as a result of technological advancements and their growing significance in education[

21]. A social robot is an autonomous or semi-autonomous robot that is made to engage in meaningful social interactions with people. The artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms that these robots are outfitted with allow them to identify and react to human emotions, actions, and social cues. They are frequently made to imitate human characteristics, such voice, gestures, and facial emotions[

22].

According to researchers, some of the behavioural effects of social robots in the classroom explain various human-robot interactions. Therefore, robots that don't attempt to behave socially could be used as teaching aids to teach pupils about technology[

23]. Social robots employ a social interface, leverage artificial intelligence and human-robot interaction, and are viewed as social creatures because of their anthropomorphism as well as their social purposes, context, and shape[

24].

These robots are distinguished by their social abilities and interface, social evocation and receptiveness, and general friendliness. As affective creatures, they are able to recognize, exhibit, and communicate changes in moods and feelings. Therefore, it is necessary to look into and assess how they interact and engage with users. Social robots can be incorporated into education and other fields thanks to their characteristics. But since there are different kinds of social robots (such Nao, Pepper, Haru, Qtrobot, Kebbi, etc.) with different responsibilities and specialties, it's critical to choose and employ the social robot that's best suited for each situation[

25].

Children are discovered to be learning with robots even while playing. As a result, analysing and assessing social robots has become critical in identifying the impact of robotics on children's cognitive, language, ethical, and social interaction skills[

26]. With the help of technology, education has been functioning as an oracle over the years. The impact of educational robots in many developing nations has received special attention. In order to determine whether production has increased or decreased, developed nations typically carry out in-depth research on the subject, host seminars, and run experiments. First Legos, which are imported from the US Robo Cup Junior, the most well-known international robot competition for schools, are the most well-liked products offered by robotic competitors in Europe[

27].

Robots are used in education to teach robotics concepts like sensors, actuators, and programming. The most frequent and popular kit is the LEGO Mindstorm. They can teach a variety of courses, including computer science, programming, robotics, and language. Similarly Nao[

28] is a humanoid robot that is particularly appealing to younger people. It teaches real-time operations, such as treatment in education, to engage students with learning issues in a 'therapeutic process'. A variety of programming languages, including Java, C++, and Python, are available.

The BeeBot is another bright, bug-like robot. This social robot teaches basic math and programming concepts to young kids. It is both simple to use and cost-effective. It can teach control, sequencing, directive language, repeats, and program sequences[

29], Romibo is a service robot that can walk, make gestures, and talk. It is controlled by a remote control and works to improve its cognitive and educational abilities[

28]. For personal assistance Kaspar, which stands for kinesics and synchronization, is a doll-like humanoid that assists educators and parents of kids with autism and other severe communication disorders. Because autistic children struggle to read facial emotions and decipher voices, Kaspar was purposefully designed with an expressive face cut[

30].

Learning electronics, languages, computers, and mechanical engineering using robots has proven to be an enjoyable experience. Because children are more drawn to technology than older people these days and because language learning was made possible by a robot, they performed better after learning than did audio and books. Social robots can be useful tools for kids studying with robot assistance. Study revealed motivational elements of robots[

31], their capacity to patiently repeat tasks, their ability to modify learning challenges[

32], and their human-like presence and interaction could all contribute to their advantages[

33]. Learning is significantly impacted by motivation, and social robots may be able to serve as learning motivators because of their traits[

34]. For instance, the Persuasive Design approach provides a variety of methods for creating technology that can inspire and engage users. This article explores the implications of Persuasive Design[

35] and its considerations for child-robot interaction (CRI) and robot-assisted learning. Research on robotics in education for children is popular topic[

33].

Studies on human-robot interaction have grown significantly as a result of the promising future of improved assistive technology in entertainment, healthcare, and education. The idea behind this method comes from the way babies understand the referents of new words. The study[

36] used two measures—the alternative forced-choice (AFC) test and gaze data analysis—to examine the possible advantages of using social robots during educational interventions based on the Fast mapping technique. While the second metric examines participants' gaze attention during training sessions, the first metric investigates retention following a 10-minute and one-week delay. Results suggest that using social robots in quick mapping therapies may improve kids' focus, engagement, and memory of new words.

Globally, robotics education is a brand-new and quickly expanding topic of study. It might give kids a fun and creative way to learn about all facets of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education. A study[

37] examined at the potential effects of robotics learning activities on the cognitive processes and capacities of children aged 6 to 8. Using a repeated measures design and a mixed methods approach, the study collected data in three waves over a period of six months. The quantitative data came from eye tracking and cognitive tests, while the qualitative data came from interviews. According to the findings, kids thought of robot education activities as games, which increased their interest in their studies. Parents also noticed that their kids were more focused on the activities than they had been six months prior. Furthermore, as indicated by the eye-tracking data visualization, children grew more concentrated on robot education activities and processed information more quickly overall over the course of six months, which was consistent with the results of assessments and interviews.

Many studies concentrate on peer-based cooperative problem-solving and how it affects cognitive development of children[

38]. Research on child-robot interaction is looking into how children might benefit from having robots as social learning partners in a variety of settings, including learning a second language[

39,

40], inquiry learning, storytelling and problem solving[

41]. In a recent study[

42], an autonomous robotic system was created to engage with kids in a problem-solving environment with the goal of determining how the robot's behavior affects the social dynamics of the group. The findings show that social robots can influence children's group problem solving techniques and team dynamics, which is consistent with recent HRI research.

We can reveal the foundations of knowledge in social robots as a taxonomy by examining various aspects of scholarly papers and producing maps of the scientific or academic landscapes. In order to shed light on the function of social robots as peers, tutors, or aids in learning activities, the current study attempts to summarize the role of social robots in education, assess their benefits and drawbacks, and look at how their presence affects the results. With a variety of robots made to cater to different developmental needs, social robots are being utilized in education more and more to improve social and cognitive abilities. The ability of social robots to engage kids in meaningful social interactions is reviewed in this section along with their current status in education. A variety of robots, including BeeBot, Kaspar, and NAO, are employed to teach social and cognitive skills. Additionally covered in this section is how robots can promote emotional growth, creativity, and problem-solving skills.

Materials and Methods

The PRISMA guidelines, which offer a standardized framework for carrying out systematic reviews, are followed in this review. The four steps of the PRISMA approach are as follows: (1) database searches are used to find studies; (2) studies are screened according to predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria; (3) full-text article eligibility is evaluated; and (4) studies that satisfy the criteria are included. This guarantees a thorough and open process for combining data regarding the efficacy of robot-mediated learning for kids. Since these are the most comprehensive and frequently used resources for the Child robot interaction, the scope of this review is limited to Google Scholar and Web of Science. The study topics, data extraction and selection, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data analysis are all included in the review methodology.

3.1. Data Selection & Search Query

Research was conducted between 2018 and 2025, and all publications published from the journal's founding in 2018 and 2025 were included. The table displays the main search phrases that were utilized. Since the word "cognition" might be used in contexts other than those directly linked to the topic, it was disregarded as a search term when used exclusively (unrelated to other pertinent terms). Additionally, this was done to improve the calibre and applicability of the publications found.

Table 1.

Searches.

| Search |

Keyword |

| 1 |

"Social robots" AND "Emotional development" OR "cognitive development" |

| 2 |

"Robot-mediated learning" OR "child- robot interaction" OR "robotics in Education “AND "Cognitive development" |

| 3 |

"Robot design" OR "robot behaviour" AND "Cognitive engagement" OR "learning outcome" |

3.1.1. Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

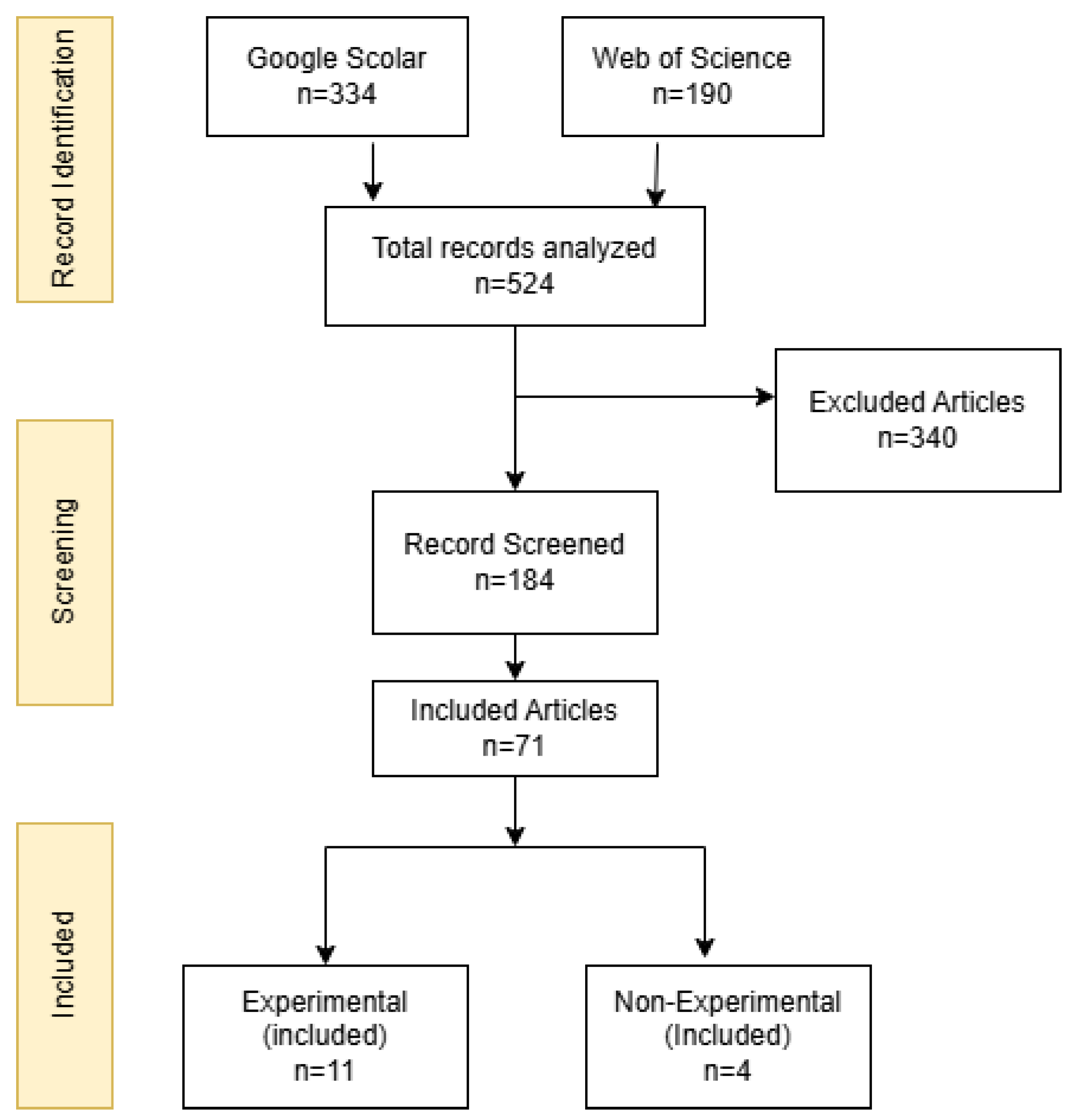

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Identified, Screened, and Included Articles.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Identified, Screened, and Included Articles.

The selection for data in this study was guided by criteria, given below:

Published articles in a peer-reviewed scientific journal between 2018 and 2025.

Research design that includes pre-test and post-test measurements, whether experimental or non-experimental (without random assignment).

Quantitative measure of the intervention's impact, sufficient for calculating the effect size.

Focus on clearly defined research questions related to the influence of social robotics on the cognitive development of children aged 0 to 15.

Emphasize the robotics-based intervention as the primary explanatory variable affecting the measured outcome, rather than other factors occurring alongside the robotic activity.

Utilize real robots or robotics kits as the main tools for manipulation.

Exclude studies that involve children or students in the design, data collection, or testing processes.

In this study, the search terms included various keywords such as "cognition" and "embodied cognition." The concept of "embodied cognition" suggests that learning is primarily mediated through the body, not just the brain, emphasizing the interconnectedness of the body and mind in cognitive processes. However, our research focused specifically on cognition, which involves learning and understanding through experience, thought, and sensory perception, rather than embodied cognition. We considered peer-reviewed, empirically supported publications, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative studies, for inclusion. The study design was required to align with the research objectives, featuring a clear definition of the purpose, goals, data collection methods, analysis, and conclusions to effectively address the research aims.

3.1.2. Data Extraction

The data was extracted on following criteria:

Age range of kids.

Type of paper i-e, Experimental, Non-Experimental

Robot type that was used during experiment.

Name of robot.

Findings of research based on their studies.

The role of robot or interaction that was used during experiment.

3.1.3. Limitations

The search criteria are restricted by the phrases "child" and "children," as well as the corresponding age range. The study sets the age range for children as 0–15 years because people older than this range may be regarded as adults depending on the societal environment of development. The literature from fields including cognitive science, clinical psychology, mind-body philosophy, experimental psychology, and neuroscience was purposefully left out of this review. This allows for the integration of findings from Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) with social science and theoretical viewpoints, hence creating prospects for future interdisciplinary study.

3.2. Methods

This section examines 15 primary studies published in 2018 and addresses key research questions. The analysis emphasizes research from 2018 onward due to the rapidly evolving field of robotics and its educational uses. This approach ensures that the review reflects the latest insights into how Robot-Mediated Learning influences children's social and cognitive development, incorporating recent advancements in pedagogy, technological innovations, and updated methodologies compared to earlier studies.

Table 2 provides a summary of included papers. Some factors that could impact the outcome including Robot design, encompassing role, autonomous level, look, emotional expressiveness, and voice. The study focuses on specific subjects, skills, and teaching approaches that impact children's learning outcomes. The major category of cognition includes inputs, observed behaviours, techniques, environmental context, abstract metaphors, offloaded cognitive processes, and external representations.

3.2.1. Information Structuring

Table 2 reports the structured data from each chosen article. Each work's primary goal, the robot utilized, its name, the number of participants, and a brief explanation of the model's or researcher's involvement are all listed in the tables. The first column lists the cognitive domain (to which they belong, architectures, empathy, and the behavioural adaption requirement), in addition to the results. Additionally, the number and kind of participants in the experimental session are given in articles that outline an experimental technique. Giving a summary of the publications in this survey and making it easier to compare them are the goals of the abstraction.

The way kids view and engage with social robots is greatly influenced by their look. Because anthropomorphic robots, like NAO[

43] and Kaspar, are sometimes made to seem like people or animals, kids may find them more relatable and interesting. For example, a humanoid robot called NAO has been used in numerous studies to teach the fundamentals of music and improve social skills, demonstrating that its human-like look makes kids feel more at ease and involved during conversations. Similarly, the expressive face of Kaspar[

58], a product created especially for kids with autism, aids in better emotion interpretation for kids who struggle with social communication.

Another essential component of social robots is their sensory capacities. Robots with sophisticated sensors—like cameras, microphones, and touch sensors—are better able to recognize and react to the emotions and behaviors of kids. For instance, Moxie[

46], a robot created to teach social and emotional skills, combines speech analysis and facial recognition to modify its interactions according to the child's emotional state. In order to establish rapport and trust, which are critical for successful learning and social development, it is imperative to be able to "read" and react to children's emotions in real time.

Furthermore, given their multimodal sensory inputs, robots like Pepper[

59] can do more sophisticated tasks with kids, like teaching them about ecological sustainability. To make learning more engaging and dynamic, these robots can provide tactile, visual, and even aural feedback. These robots are more effective in a variety of educational contexts because of their capacity to process and react to many sensory inputs, which enables them to adjust to various learning preferences and styles.

Another key component of social robots' efficacy is their mobility and gesture capabilities. Children are frequently more interested in robots that can imitate human movements and gestures, like NAO and Tega[

50]. For instance, it has been demonstrated that NAO's capacity to make human-like gestures improves children's educational experiences, especially when it comes to teaching social skills and music. Similar to this, Tega, a robot made for early childhood education, keeps kids interested and enhances their impression of the robot as a social companion by using expressive gestures.

It was also observed that robot's capacity to support physical activities, which are critical for both cognitive and motor development, is also influenced by movement. Simple movements are used by robots like BeeBot[

48], which are meant for younger kids, to teach them spatial awareness and fundamental programming ideas. These robots show that, especially in the early years, even minimal movement skills can be useful for involving kids and promoting their cognitive development.

Children who engage with emotionally expressive robots are more likely to acquire healthy coping and problem-solving techniques, according to studies[

6]. One important aspect of social robots that can have a big influence on kids' social and emotional development is their emotional expressiveness. Children are more likely to form emotional bonds with robots that can portray emotions through body language, voice modulation, and facial expressions. The robot Moxie[

46], for example, can convey a variety of emotions, which aids in children's emotional literacy and resilience development.

Social robots' capacity to promote kids' social and cognitive development depends heavily on their functioning and design. Children are more likely to interact with and form positive relationships with anthropomorphic, emotionally expressive, and culturally sensitive robots. Furthermore, more individualized and efficient learning experiences can be offered by robots with sophisticated sensory capacities, mobility, and flexibility. It will be crucial to investigate these traits and their effects on kids' development as the area of social robotics develops, especially in multicultural and diverse educational environments.

The section describes the inclusion and exclusion criteria, data extraction techniques, and limitations of the study. The review employs a methodical approach to analyze research on robot-mediated learning, with a focus on children's cognitive development and the role of social robots. It includes both experimental and non-experimental studies that investigate the influence of social robots on children's cognitive development.

3. Results

Based on summary provided in

Table 2, multiple robots were used. Some of these robots are humanoid like NAO, Kasper, Moxie, Jibo, Tega, it was observed that they appear to be intimately linked to the development of children's social cognitive skills and mobility. This is due to the fact that such robots can mimic movements, which helps kids become more mobile.

The potential of social robots such as Cozmo, iCub, RIDER, Bee-Bot, CRAB, and mBot to engage kids, promote learning, and enhance social-emotional abilities is continuously shown by research findings. According to studies, these robots can significantly improve cognitive development, especially in domains like creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. Along with offering a forum for emotional expression and control, they can help enhance social skills like empathy, cooperation, and communication. It's important to remember, though, that the efficacy of these robots varies based on a number of things, including the age of the child, personal needs, and the particular design and functioning of the robot.

It is also examined how social robots can help youngsters develop their cognitive abilities, especially in areas like emotional growth and social interaction. Research indicates that kids can develop close relationships with robots, which boosts their level of involvement and enhances their social skills. Despite encouraging research findings, there are still obstacles to overcome. Because there are so few research, care must be taken when interpreting the results. Additionally, research results from many age groups cannot be extrapolated to a single target audience or age group. Key discoveries, however, show that children pay attention to robots and can learn from them in a variety of contexts from a young age. However, this may depend on the robot's design, which may take into account the elements covered below.

The basic factor here to determine is interaction of a child with robot, how the child will perceive? How the kid will interact with robot? Foundational cognitive abilities like language acquisition, memory, problem-solving, and executive functions are growing quickly during the early years of life. During this time, early exposure to robot-mediated learning can make a big difference. Many robot-mediated learning activities revolve around play and hands-on interaction, which are often the most effective learning methods for kids in this age range. It is appropriate to investigate robots as social and educational partners at this age since cognitive growth at this level also encompasses social cognition, such as comprehending the viewpoints of others.

A major component of social robots' efficacy is their capacity to adjust to the requirements and preferences of certain kids. Children are more likely to be engaged and have their cognitive and social development supported by robots that can tailor their interactions according to the age, developmental stage, and learning style of the child. For instance, the robot Pepper has been utilized to offer individualized educational experiences, modifying its interactions according to the child's development and reactions.

The review emphasizes how robot-mediated learning can help children's cognitive development. Early robot exposure can greatly improve cognitive abilities including creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. When compared to conventional teaching approaches, the employment of robots such as Pepper and Cozmo to engage children in educational activities has been shown to boost motivation and engagement.

4.1. Developmental Stage and Age Cohorts

Children's interactions with social robots and how well they improve cognitive abilities are strongly influenced by their age. While older kids can work on more difficult problem-solving and programming exercises, younger kids might mostly concentrate on sensory exploration and simple interactions[

60]. A wide range of cognitive, social, and emotional development occurs between the ages of 0 and 18. Children in this range go through different developmental phases, each of which is distinguished by particular emotional reactions, social interactions, and cognitive capacities.

Infants (0-1) years: Children at this age are mostly interested in developing their fundamental motor abilities and exploring their senses. Simple, sensory-based tasks like visual tracking or aural replies are probably what people would do when interacting with robots. For instance, research indicates that babies are attracted to robots that imitate human facial expressions and movements, which can aid in the development of their early senses and motor skills[

61].

Toddlers(1-3) years: Toddlers start to interact with their surroundings more intricately and acquire language abilities. For this age group, robots could concentrate on language learning, fundamental social interactions, and basic problem-solving activities. For example, young children have been taught fundamental math and programming principles by robots such as BeeBot[

29].

Preschoolers (3-6 years): Rapid cognitive growth, encompassing memory, imagination, and social cognition, characterizes this stage. Through interactive games, role-playing, and narrative, robots can improve these abilities. For instance, NAO robots have been utilized to improve social skills and teach the fundamentals of music to this age range[

43].

School-age children (6-12 years): This age group of kids gains sophisticated problem-solving abilities and logical thinking. Programming, critical thinking, and cooperative problem-solving are all skills that robots can impart. Research has indicated that robots such as mBot and LEGO Mindstorms are useful for improving cognitive abilities in this age range[

48].

Adolescents (12-18 years): Abstract thought, identity development, and increasingly intricate social interactions are also part of this period. In addition to supporting social and emotional development, robots can be utilized to teach complex STEM ideas. As an illustration of how robots may assist with complicated cognitive and social activities, Pepper has been used to get teenagers talking about ecological sustainability[

62].

4.1.1. Growth and Learning

Learning and development phases (at the ages of 1, 3, 6, 7, and puberty) sometimes resolve unnoticed and calmly and other times may cause a stark conflict with parents and the environment. However, it is possible to define certain "stages" that are dependent on age but primarily defined by the biological maturity of the organism, uneven development of the psyche, and the accumulated social and cognitive experiences of a particular individual. While the significance of prior experiences and personal traits increases with age, leading to discernible differences among similarly aged older children, the development of younger children may be reliably described and predicted using broad age-based trends[

63]. Furthermore, different viewpoints on the continuity and discontinuity of the stages in a child's development exist within the field of developmental science.

Based on results children learning ability vary according to their age, to elucidate the criteria related to children of particular age groups and to show how this knowledge affects the way that interactions with children are planned. To create a thorough grasp of the many stages, we shall utilize the knowledge offered by well-known developmental theories that are provided in

Table 3.

4.1.2. Age Factors

Up to 1 Year: This little time span includes a significant shift in behaviour, starting with the innate fundamental reflexes (crying, sucking, gripping, and watching) and progressing to intentional behaviours and the capacity for purposeful communication with others[

68]. From fixating and following randomly to a voluntary process, attention evolves into a dominant function. Sensorimotor and self-motion experience form the foundation for cognitive functions.

Up to 3 Year (1-3): The toddler studies the environment and the properties of objects by directly manipulating and recognizing, and develops memory to recognize these attributes in other objects (e.g., small and large, light and heavy, quiet and loud). Basic speech forms, imitation of adults, and other forms of imitation manifest in behaviour and actions with toys[

51]. Perception is the dominant mental function at this stage, which results in the active formation of sensory experience.

Up to 6 Years (3-6): A child's memory, a prominent mental function, helps them memorize a lot of information, but they have trouble processing it correctly. This results in constrained, frequently "magical," interpretations of causal relationships that are based on particular, rather than generalized, experiences. The majority of the cognitive function is anthropomorphic, animistic, and egocentric[

50]. At this age, role-playing with classmates and fictional characters is the most popular hobby. Children investigate and learn how to behave in accordance with societal norms by taking on a variety of social roles.

Up to 12 Years (6-12): As the infant learns to construct and explain causal links that extend beyond immediate sense, logical thinking takes over. Even yet, graduate students still have trouble understanding hypothetical and abstract ideas, and it takes work to apply logical thinking to real-world situations[

69]. One's own sense of boundaries in different contexts causes behaviour to become more intentional and self-controlled. Children who spend more time with their peers outside of their familial circle develop friendships.

Up to 18 Years (12-18): This is a time of self-discovery and identity formation, which triggers a hormonal explosion, frequently results in instability and unpredictability, and presents difficulties for motivation and academic achievement. Primary (abstract) logical thinking permits working with hypothetical and abstract concepts and is no longer based on concrete examples. This intellectual growth promotes debates and conversations in a more sophisticated way.

4.1.3. Other Characteristics Affecting Perception

Age gives a child knowledge about the duties and activities that are normal and significant for their developmental stage, so they are easily accepted. A youngster that naturally participates in such activities develops his or her own interpretation and level of interest, which eventually fuels the connection[

70]. This age-appropriate content matching idea is applicable to all work with children, including educational, therapeutic, psychological, cognitive, sports-related, and social work, as well as product design for kids.

Age-appropriate activities for a baby of age up to 1 year could include manipulating items, orienting toward a stimulus, playing games that require visual contact and emotional reaction, and mimicking basic gestures, movements, and sounds. Because establishing an emotional bond and trust is a crucial developmental activity. However, for a toddler aged(1-3y), tasks like manipulating and making multimodal contact with physical items or navigating space could be considered age-appropriate. Introducing new items or applications by peers or adults could maintain interest and cognitive function.

Kids of age 3-6, Innovative activities that inspire children to create new items or modify old ones in accordance with their age, of durability and ease of maintenance, of creativity, and of cognitive skills could be considered age-appropriate activities. On the other hand, for kids of age 6-12, Activities, such as games with rules and success criteria, feedback, and progress communication, should be designed to test and enhance logical thinking. Individual accomplishments are significant in this aspect. For kids of age 12-18, It is more difficult to create a setting of meaningful shared interaction than to direct the interaction at a particular youngster. The sub stages, lengths of time, and particular challenges that teenagers may encounter throughout this time vary widely.

4.1.4. Cultural Factors

Every social connection we have is influenced by culture. Culture has an impact on how we think about, perceive, and comprehend other people as well as our environment, in addition to how we behave as a social group[

71]. People are exposed to and participate in a wide variety of cultural norms and practices because of the globalized multicultural society in which we currently live. According to research[

72], a variety of factors affect our behaviour, thoughts, and feelings during HRIs. These include the motivating elements that support a user's commitment to a robot or our impression of robots exerting effort during engagement. For design of a robot with cultural factors and to prevent discomfort or rejection, a robot's physical attributes should be in line with aesthetics and cultural norms. Skin tone, hairstyle, attire, and general body shape are all examples of this. Conversely, robots should modify their behaviour and communication style to conform to cultural norms for social interaction, such as proper greetings, eye contact, personal space, and voice intonation. The findings demonstrate how well different social robots, including BeeBot, Pepper, and NAO, may improve kids' social and cognitive abilities. According to the research, robots can enhance learning outcomes, motivation, and engagement, especially in domains like creativity, problem-solving, and emotional control. However, a number of variables, including age, design, and usage context, affect how effective robots are.

5. Discussion

Foundational cognitive abilities like language acquisition, memory, problem-solving, and executive functions are growing quickly during the early years of life, but many factors affecting robot design involve in this context for instance, children's cognitive and emotional reactions to robots can be strongly influenced by the environment in which they interact with them. For instance, interactions in a naturalistic classroom or home environment might produce different outcomes than those in a controlled laboratory setting. Robot-mediated learning can be made more or less successful by environmental conditions like noise levels, peer presence, and the availability of other stimuli. Similarly, Children's reactions to robot interactions can also be influenced by the presence of peers, parents, or other caregivers. Collaborative play with peers or positive reinforcement from adults can improve learning outcomes and engagement.

On the other hand, unfavorable comments or disinterest from others could make robot-mediated interventions less successful. Another important factor to be considered is tha a lot of research on robot-mediated learning is short-term and concentrates on results right away. To evaluate the long-term effects of robot interactions on kids' cognitive and emotional development, longitudinal research is required. While Most research focuses on certain populations or age ranges. A more thorough grasp of how various kids react to robots might be possible by broadening the participant pool to encompass a greater range of ages, skill levels, and cultural backgrounds. This would also make it easier to spot any possible biases or restrictions in the current study. It is appropriate to investigate robots as social and educational partners at this age since cognitive growth at this level also encompasses social cognition, such as comprehending the viewpoints of others.

5.1. RQ1. How Can Children's Positive Emotional Development—Like Resilience and Confidence— Be Fostered by Social Robots?

Children's views and interactions with social robots are discussed in this section. First of all, children's perceptions of robots are frequently shaped by fictional representations, which frequently blend technological innovations with human-like traits and can reinforce preconceptions. Second, kids often anthropomorphize robots by giving them human-like feelings and thoughts. By demonstrating healthy coping strategies and offering emotional support, social robots can promote children's emotional development in terms of good views. Trust, robot embodiment, and conduct are some of the factors that have a big impact on how kids connect. According to studies[

7], children may benefit from emotional regulation assistance from robots that exhibit human-like traits including facial expressions and careful listening.

Depending on their particular characteristics, cultural upbringing, and past experiences, children's emotional reactions to robots might differ greatly. Certain children may display positive emotions like delight and curiosity, while others may experience dread or worry, particularly if the robot's appearance or behavior is seen to be strange or unfamiliar. When designing and implementing robotic treatments, this heterogeneity should be taken into account since it may affect the efficacy of robot-mediated learning. Emotional attachment to robots can improve learning results and engagement, but it can also result in emotional dependence or over-reliance. Children who struggle with social communication may develop close relationships with robots in therapeutic settings, which could make it more difficult for them to use newly acquired abilities in real-world situations. Future studies should examine methods for striking a balance between fostering social skills and independent study and emotional engagement.

Children's emotional reactions are greatly influenced by the emotional expressiveness of robots, including body language, voice modulation, and facial expressions. Robots that are too expressive, however, could cause misunderstandings or irrational expectations, particularly in younger kids who are still learning about emotions. To make sure that robots are viewed as helpful tools rather than emotional stand-ins, designers should strive for a balance between expressiveness and simplicity.

Additionally, studies(n=12) show that children's engagement and learning are greatly impacted by a robot's social presence, including perceived intellect and attraction. Robots having a more social presence tend to engage with children more favourably, which enhances rapport and improves learning results.

5.2. RQ2. How Children Cognitive Development Can Be Fostered by Early Exposure to Robot Mediated Learning?

Children go through several evolutionary phases from a very young age as they develop, during which time their cognitive and physiological abilities advance as a result of constant interaction with their environment. Leading researchers in the field of children's motor and cognitive development were Piaget (

Table 3.) and Inhelder, and their hypothesis[

64]. In recent years, there has been a lot of interest in the incorporation of robotics into early childhood education. Attracting children's attention and inspiring them to learn is one of the main ways robots promote cognitive development. Robots provide an engaging and dynamic learning environment in contrast to conventional teaching techniques, which are occasionally thought of as boring. Their captivating looks, expressive gestures, and capacity to offer tailored feedback can greatly boost kids' drive and attention.

One of the study[

73], examined how a social robot called "Pepper" affected the way children participated in educational activities. According to the study, kids who interacted with Pepper showed noticeably greater levels of motivation and engagement than kids in a control group. On the other hand, Children can gain important opportunity to acquire critical social and emotional skills through interacting with robots. Children can be encouraged to speak, express their feelings, and take turns by using robots as social partners. Children can gain empathy, social awareness, and the capacity to recognize and address the needs of others through this connection.

In order to demonstrate this, a study[

74] looked at how children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) responded to a robot-assisted intervention. According to the study, kids who engaged with a social robot showed notable gains in their ability to communicate socially, including better verbal communication, more eye contact, and improved social interaction. Research on robotic technology, particularly assistive robotics for babies, is expanding and could be crucial for early age children with a variety of cognitive impairments. In fact, it has been discovered[

75] that babies are frequently drawn to robotic gadgets, and that these gadgets may help youngsters with physical limitations play and exercise as well as those with cognitive difficulties study.

For example, when compared to traditional methods, humanoid robot motion demonstrations offer a number of special benefits for researching baby motion adaption. Interactive humanoid robots may hold infants' interest longer than inanimate toys because they prefer face-to-face interactions[

61]. Additionally, tiny humanoid robots are capable of making movements akin to those of newborns. This feature might make it easier for the robot to encourage babies to mimic desirable motion patterns. This premise was put to the test and worked well. In fact, the scientists used two socially assistive robots to create a pediatric learning environment that would provide motor treatments.

Early exposure to robot-mediated learning has been shown to considerably improve children's cognitive development. According to studies conducted that year, Robot-mediated learning can help kids become more motivated and engaged, develop their social-emotional skills, sharpen their problem-solving abilities, and expose them to computational thinking. Additionally, robot-mediated learning can meet the specific requirements of kids with special needs and offer individualized learning experiences.

To find out if people intentionally take a stand against the humanoid robot iCub, a survey was carried out. Their findings demonstrated that the deliberate stance toward humanoid robots can occasionally be induced. Furthermore, the use of non-invasive neuroimaging methods (such as fMRI) in neuroscience makes it possible to examine how the human brain processes social information when interacting with robots[

76]. For example, According to one study[

77], human-human interaction significantly increased the activation of brain markers of metalizing and social motivation compared to human-robot interaction.

.

Even though social robots have many advantages, it's vital to take into account the drawbacks and restrictions of using them, especially when it comes to accessibility issues, ethical issues, and individual variations in children's reactions. In conclusion, it has been demonstrated that early exposure to robot-mediated learning improves children's cognitive development by raising their level of motivation, engagement, and social-emotional abilities..

5.3. RQ3. What Are the Considerations for Further Design of the Robot's Physical Appearance and Behaviour Influence Children's Cognitive Engagement?

This section emphasizes how important age is in creating successful relationships between kids and social robots. Additionally, it is noted that children's cognitive capacities and robot-interaction behaviours varies greatly depending on their age. While older kids can participate in more intricate problem-solving and programming exercises, younger kids might mostly concentrate on sensory exploration and basic interactions[

72]. Older kids might flourish on more difficult tasks that call for critical thinking and problem-solving, younger kids might benefit from straightforward, entertaining interactions that prioritize language development and basic social skills.

Additionally, research outlines important milestones in cognitive, social, and emotional development as well as essential developmental phases throughout life. It talks about how these phases of development affect how kids interact with the outside world and how these things should be taken into account while creating learning experiences that use robots[

70]. Culture has an impact on every social relationship we have. It is possible to clarify the criteria pertaining to children of specific age groups and demonstrate how this information influences the planning of interactions with children. Children's learning abilities also differ depending on their age. We will use the information supplied by well-known developmental theories, which are included in

Table 3, to establish a comprehensive understanding of the various stages.

Children's expectations and comfort levels when dealing with robots are influenced by cultural norms and values, which also affect how they perceive social interactions. Perhaps Cultural norms surrounding social interaction and group dynamics can have an impact on how children engage with robots and other children in educational settings; consequently, robots must be designed to assist these connections in a way that is appropriate for the culture. We can optimize the potential of social robots to assist children's cognitive and socio-emotional development by customizing interactions to each child's unique needs and talents.

In this work, we primarily focused on papers that report enough information about the children interacting with the robot, such as their behaviours, responses, differences in task performance, unusual and typical reactions, and the results indicate the impact on their cognitive skills, in order to illustrate the child factor in the studies. We observe that children's development heavily relies on trying new things, making mistakes, conquering obstacles, and receiving both positive and negative reinforcement in a wide range of social, physical, and intellectual contexts. Human-robot interaction can be promoted and important insights for maximizing human-robot social interactions can be obtained by applying the knowledge acquired in human-human interaction[

78].

Although thorough, the two databases used for the review—Google Scholar and Web of Science—may not have included all pertinent research published in other databases or in languages other than English. The review only included papers that were published between 2018 and 2025, which would have left out previous studies that might have offered background information or fundamental understandings of the evolution of robot-mediated learning.

The robots employed in the evaluated experiments differed greatly in terms of their autonomy, capability, and design. Because of this variety, it is challenging to make generalizations regarding the efficacy of particular robot features or interaction modalities. Standardized protocols for robot design and interaction may be useful for future studies.

To evaluate the long-term effects of robot-mediated learning on kids' cognitive and social development, future research should concentrate on longitudinal studies. Furthermore, cross-cultural comparisons may offer insightful information about how cultural variations affect kids' interactions with robots. Lastly, further study is required to examine the moral ramifications of deploying social robots in classrooms, especially with regard to kids' privacy and emotional health.

Our analysis demonstrates research trends in the use of social robots to investigate social and cognitive concepts, including early conversational abilities, action understanding, improvement in perception, learning enhancement. Robots have also been utilized in several research to investigate emotions, reading comprehension, and computational reasoning[

79]. The majority of research, we discovered, concentrated on whether children view robots as social partner their cognitive skills improve or not. Another significant discovery was that young children's perceptions, comprehensions, and reactions to social robots are significantly influenced by both the robots' behaviour and appearance[

50,

51,

57,

79]. Through interesting and interactive learning experiences, social robots have demonstrated the ability to improve children's cognitive abilities, resilience, and self-assurance. The child's age, developmental stage, cultural background, and the robot's design are some of the variables that affect how effective these robots are. Older children can work on more difficult problem-solving activities, while smaller children benefit from sensory exploration and simple interactions. Children's interactions with robots are also greatly influenced by environmental factors and cultural norms. Notwithstanding the encouraging results, issues including emotional reliance, accessibility, and moral dilemmas must be resolved. To completely comprehend the long-term effects of robot-mediated learning, longitudinal research and larger participant pools are necessary.

6. Conclusions

The research conducted between 2018 and 2025 on the effectiveness of social robots in cognitive development was methodically described in this paper. The study has shown three key areas to help social robots greatly support the social integration of kids with disabilities: (1) children's perceptions of (2) the evaluation of social robots in cognitive fields, (3) the search for various types of social robots and their appropriateness by category of impairments. Through research questions it was indicated that why age and cultural factors were crucial in the robot's design and how good emotional outcomes like resilience and confidence increase the effectiveness of robots. Looking ahead, the advent of social robots presents both potential and challenges. As technology advances, social robots have the potential to become increasingly incorporated into educational and therapeutic environments, providing children with tailored and adaptive learning experiences. Future study should focus on longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impacts of robot-mediated learning on children's cognitive and social development. The effectiveness of the robot's increased social presence is not limited to the current connection, but also contribute to lessening children's overall relational unease with robots.

References

- T. N. Beran, A. Ramirez-Serrano, R. Kuzyk, M. Fior, and S. Nugent, ‘Understanding how children understand robots: Perceived animism in child–robot interaction’, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, vol. 69, no. 7, pp. 539–550, Jul. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ekaterina Pashevich1, ‘Can communication with social robots influence how children develop empathy? Best-evidence synthesis | AI & SOCIETY’. AI & SOCIETY (2022) 37:579–589. [CrossRef]

- L. Malinverni, C. Valero, M. M. Schaper, and I. G. de la Cruz, ‘Educational Robotics as a boundary object: Towards a research agenda’, International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, vol. 29, p. 100305, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Blancas et al., ‘Analyzing children’s expectations from robotic companions in educational settings’, in 2017 IEEE-RAS 17th International Conference on Humanoid Robotics (Humanoids), Nov. 2017, pp. 749–755. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Boada, B. R. Maestre, and C. T. Genís, ‘The ethical issues of social assistive robotics: A critical literature review’, Technology in Society, vol. 67, p. 101726, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rebecca Stower, Natalia Calvo-Barajas, · Ginevra Castellano, and Arvid Kappas, ‘A Meta-analysis on Children’s Trust in Social Robots | International Journal of Social Robotics’. International Journal of Social Robotics (2021) 13:1979–2001. [CrossRef]

- ‘E. A. Björling, K. Thomas, E. J. Rose, and M. Cakmak, ‘Exploring Teens as Robot Operators, Users and Witnesses in the Wild’, Front. Robot. AI, vol. 7, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Kang, K. Makimoto, R. Konno, and I. S. Koh, ‘Review of outcome measures in PARO robot intervention studies for dementia care’, Geriatric Nursing, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 207–214, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Iolanda Leite, Marissa McCoy, Monika Lohani, Daniel Ullman, and Nicole Salomons, ‘Frontiers | Narratives with Robots: The Impact of Interaction Context and Individual Differences on Story Recall and Emotional Understanding’. Front. Robot. AI , 12 July 2017 Sec. Humanoid Robotics Volume 4 - 2017. [CrossRef]

- Eduard Fosch-Villaronga, Alex Barco, Beste Özcan, Jainendra Shukla, ‘An Interdisciplinary Approach to Improving Cognitive Human-Robot Interaction – A Novel Emotion-Based Model’, vol. 290, pp. 195–205.

- C. de Jong, R. Kühne, J. Peter, C. L. V. Straten, and A. Barco, ‘What Do Children Want from a Social Robot? Toward Gratifications Measures for Child-Robot Interaction’, in 2019 28th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Oct. 2019, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- M. Heerink et al., ‘A field study with primary school children on perception of social presence and interactive behavior with a pet robot’, in 2012 IEEE RO-MAN: The 21st IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Sep. 2012, pp. 1045–1050. [CrossRef]

- Cerekovic, O. Aran, and D. Gatica-Perez, ‘Rapport with Virtual Agents: What Do Human Social Cues and Personality Explain?’, IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 382–395, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. G. Baker, E. M. Watlington, and C. R. Knee, ‘The role of rapport in satisfying one’s basic psychological needs’, Motiv Emot, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 329–343, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Lutz, M. Schöttler, and C. P. Hoffmann, ‘The privacy implications of social robots: Scoping review and expert interviews’, Mobile Media & Communication, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 412–434, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Naneva, M. Sarda Gou, T. L. Webb, and T. J. Prescott, ‘A Systematic Review of Attitudes, Anxiety, Acceptance, and Trust Towards Social Robots’, Int J of Soc Robotics, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1179–1201, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S.-E. Chien et al., ‘Age Difference in Perceived Ease of Use, Curiosity, and Implicit Negative Attitude toward Robots’, J. Hum.-Robot Interact., vol. 8, no. 2, p. 9:1-9:19, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Ferraz, A. Câmara, and A. O’Neill, ‘Increasing Children’s Physical Activity Levels Through Biosymtic Robotic Devices’, in Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, in ACE ’16. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Nov. 2016, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- D. Robert and V. van den Bergh, ‘Children’s Openness to Interacting with a Robot Scale (COIRS)’, in The 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Aug. 2014, pp. 930–935. [CrossRef]

- C. de Jong, J. Peter, and R. Kuhne, ‘Children’s Intention to Adopt Social Robots: A Model of its Distal and Proximal Predictors | International Journal of Social Robotics’. International Journal of Social Robotics (2022) 14:875–891. [CrossRef]

- P. T, K. S, and B. M, ‘Social Robotics in Education: State-of-the-Art and Directions | SpringerLink’. Vol 67, pp 689-700.

- C. Breazeal, ‘Social interactions in HRI: the robot view’, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews), vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 181–186, May 2004. [CrossRef]

- X. Tang and J. Chu, ‘Inclusive Design: Task Specified Robots for Elderly’, Advances in Education, Humanities and Social Science Research, vol. 1, no. 1, Art. no. 1, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Hegel, C. Muhl, B. Wrede, M. Hielscher-Fastabend, and G. Sagerer, ‘Understanding Social Robots’, in 2009 Second International Conferences on Advances in Computer-Human Interactions, Feb. 2009, pp. 169–174. [CrossRef]

- H. Mahdi, S. A. Akgun, S. Saleh, and K. Dautenhahn, ‘A survey on the design and evolution of social robots — Past, present and future’, Robotics and Autonomous Systems, vol. 156, p. 104193, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Y. Pai, A. Shetty, T. K. Dinesh, A. D. Shetty, and N. Pillai, ‘Effectiveness of social robots as a tutoring and learning companion: a bibliometric analysis’, Cogent Business & Management, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 2299075, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. J. S. Matthijs and K. Elly, ‘Attitudes towards Social Robots in Education: Enthusiast, Practical, Troubled, Sceptic, and Mindfully Positive’. Robotics 2021, 10(1), 24. [CrossRef]

- Robaczewski, J. Bouchard, K. Bouchard, and S. Gaboury, ‘Socially Assistive Robots: The Specific Case of the NAO’, Int J of Soc Robotics, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 795–831, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Gambin, ‘THE BEE-BOT IN THE ASSESSMENT FOR LEARNING OF MATHEMATICAL CONCEPTS’.

- L. J. Wood, A. Zaraki, B. Robins, and K. Dautenhahn, ‘Developing Kaspar: A Humanoid Robot for Children with Autism’, Int J of Soc Robotics, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 491–508, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Belpaeme et al., ‘Guidelines for Designing Social Robots as Second Language Tutors’, Int J of Soc Robotics, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 325–341, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, C.-M. Huang, and B. Scassellati, ‘Toward Effective Robot--Child Tutoring: Internal Motivation, Behavioral Intervention, and Learning Outcomes’, ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 2:1-2:23, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Belpaeme , J. Kennedy, and A. Ramachandran, ‘Social robots for education: A review | Science Robotics’. 22 Aug 2018 Vol 3, Issue 21. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/. [CrossRef]

- C. Zaga, M. Lohse, K. P. Truong, and V. Evers, ‘The Effect of a Robot’s Social Character on Children’s Task Engagement: Peer Versus Tutor’, in Social Robotics, A. Tapus, E. André, J.-C. Martin, F. Ferland, and M. Ammi, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015, pp. 704–713. [CrossRef]

- H. Oinas-Kukkonen and M. Harjumaa, ‘Persuasive Systems Design: Key Issues, Process Model, and System Features’, CAIS, vol. 24, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Esfandbod et al., ‘Fast mapping in word-learning: A case study on the humanoid social robots’ impacts on Children’s performance’, International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, vol. 38, p. 100614, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu et al., ‘Effects of Robotics Education on Young Children’s Cognitive Development: a Pilot Study with Eye-Tracking’, J Sci Educ Technol, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 295–308, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sebo, B. Stoll, B. Scassellati, and M. F. Jung, ‘Robots in Groups and Teams: A Literature Review’, Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact., vol. 4, no. CSCW2, p. 176:1-176:36, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Kennedy, P. Baxter, E. Senft, and T. Belpaeme, ‘Social robot tutoring for child second language learning’, in 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Mar. 2016, pp. 231–238. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Kory-Westlund* and C. Breazeal, ‘Frontiers | A Long-Term Study of Young Children’s Rapport, Social Emulation, and Language Learning With a Peer-Like Robot Playmate in Preschool’. Sec. Human-Robot Interaction Volume 6 - 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Charisi, E. Gomez, G. Mier, L. Merino, and R. Gomez, ‘Child-Robot Collaborative Problem-Solving and the Importance of Child’s Voluntary Interaction: A Developmental Perspective’, Front. Robot. AI, vol. 7, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Charisi, L. Merino, M. Escobar, F. Caballero, R. Gomez, and E. Gómez, ‘The Effects of Robot Cognitive Reliability and Social Positioning on Child-Robot Team Dynamics’, in 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), May 2021, pp. 9439–9445. [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A. Meghdari, M. Alemi, and H. R. Pouretemad, ‘Teaching music to children with autism: A social robotics challenge’, Scientia Iranica, vol. 26, no. Special Issue on: Socio-Cognitive Engineering, pp. 40–58, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Y. Fung et al., ‘Exploring the impact of robot interaction on learning engagement: a comparative study of two multi-modal robots’, Smart Learn. Environ., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 12, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Ghiglino, F. Floris, De Tommaso, Davide, and K. Kompatsiari, ‘Artificial scaffolding: Augmenting social cognition by means of robot technology -Autism Research. 2023;16:997–1008. [CrossRef]

- N. Hurst, C. Clabaugh, R. Baynes, J. Cohn, D. Mitroff, and S. Scherer, ‘Social and Emotional Skills Training with Embodied Moxie’, Apr. 27, 2020, arXiv: arXiv:2004.12962. arXiv:arXiv:2004.12962. [CrossRef]

- T. Schodde, L. Hoffmann, S. Stange, and S. Kopp, ‘Adapt, Explain, Engage—A Study on How Social Robots Can Scaffold Second-language Learning of Children’, J. Hum.-Robot Interact., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 6:1-6:27, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Mukhasheva, K. Ybyraimzhanov, K. Naubaeva, A. Mamekova, and B. Almukhambetova, ‘The Impact of Educational Robotics on Cognitive Outcomes in Primary Students: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Studies’, EUROPEAN J ED RES, vol. volume–12–2023, no. volume–12–issue–4–october–2023, pp. 1683–1695, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. castelano, De Carolis Berardina, and F. D’Errico, ‘PeppeRecycle: Improving Children’s Attitude Toward Recycling by Playing with a Social Robot | International Journal of Social Robotics’. Volume 13, page 97-111,(2021). Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12369-021-00754-0.

- J. M. Kory-Westlund and C. Breazeal, ‘Exploring the Effects of a Social Robot’s Speech Entrainment and Backstory on Young Children’s Emotion, Rapport, Relationship, and Learning’, Front. Robot. AI, vol. 6, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- V. Bamicha and A. Drigas, ‘ToM & ASD: the Interconnection of Theory of Mind with the Social-emotional, Cognitive Development of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. the Use of ICTs as an Alternative Form of Intervention in ASD’, Technium Social Sciences Journal, vol. 33, pp. 42–72, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. De Vit, A. Brandse, E. Krahmer, and P. Vogt, ‘Varied Human-Like Gestures for Social Robots | Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction’. pages 359-367, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Benvenuti and E. Mazzoni, ‘Enhancing wayfinding in pre-school children through robot and socio-cognitive conflict’, Brit J Educational Tech, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 436–458, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- PopBots : leveraging social robots to aid preschool children’s artificial intelligence education’. june, 2018. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/122894.

- X. Dong, Hu. Liang, and X. Ding, ‘Enhancing children’s cognitive skills: An experimental study on virtual reality-based gamified educational practices | Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- S. Ali, T. Moroso, and C. Breazeal, ‘Can Children Learn Creativity from a Social Robot?’, in Proceedings of the 2019 on Creativity and Cognition, San Diego CA USA: ACM, Jun. 2019, pp. 359–368. [CrossRef]

- S. Lemaignan, N. Newbutt, and L. Rice, ‘“It’s Important to Think of Pepper as a Teaching Aid or Resource External to the Classroom”: A Social Robot in a School for Autistic Children | International Journal of Social Robotics’. International Journal of Social Robotics (2024) 16:1083–1104. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Wood, A. Zaraki, B. Robins, and K. Dautenhahn, ‘Developing Kaspar: A Humanoid Robot for Children with Autism’, Int J of Soc Robotics, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 491–508, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Lemaignan, N. Newbutt, L. Rice, and J. Daly, ‘“It’s Important to Think of Pepper as a Teaching Aid or Resource External to the Classroom”: A Social Robot in a School for Autistic Children’, Int J of Soc Robotics, vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 1083–1104, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y.-C. Chen, S.-L. Yeh, W. Lin, H.-P. Yueh, and L.-C. Fu, ‘The Effects of Social Presence and Familiarity on Children–Robot Interactions’, Sensors (Basel), vol. 23, no. 9, p. 4231, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Funke et al., ‘A Data Collection of Infants’ Visual, Physical, and Behavioral Reactions to a Small Humanoid Robot’, in 2018 IEEE Workshop on Advanced Robotics and its Social Impacts (ARSO), Sep. 2018, pp. 99–104. [CrossRef]

- G. castelano, De Carolis Berardina, and F. D’Errico, ‘PeppeRecycle: Improving Children’s Attitude Toward Recycling by Playing with a Social Robot | International Journal of Social Robotics’. Volume 13, page 97-111,(2021). Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12369-021-00754-0.

- M. Judith, ‘Child and adolescent development for educators | CiNii Research’., 2002 ISBN 0072322357.

- J. Piaget and M. Pie, ‘The Psychology of Intelligence | D.E Berlyne, Jean Piaget, Malcolm Pie’.,pages 216, 2003. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Norton, ‘Diversity, Early Socialization, and Temporal Development: The Dual Perspective Revisited | Social Work | Oxford Academic’, 38(1), 82–90. 1993.

- R. W. Rieber, The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky: The History of the Development of Higher Mental Functions. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- ‘D. B. El’konin, ‘TOWARD THE PROBLEM OF STAGES IN THE MENTAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE CHILD |’. 1972. [CrossRef]

- C. Filippini and A. Merla, ‘Systematic Review of Affective Computing Techniques for Infant Robot Interaction | International Journal of Social Robotics’. International Journal of Social Robotics (2023) 15:393–409. [CrossRef]

- M. Ale, M. Sturdee, and E. Rubegni, ‘A systematic survey on embodied cognition: 11 years of research in child–computer interaction’, International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, vol. 33, p. 100478, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Mattia., ‘The Handbook of Developmentally Appropriate Toys - ProQuest’. Vol. 15, Iss. 1, (2023): 112-114.

- V. Lim and R. Maki, ‘Social Robots on a Global Stage: Establishing a Role for Culture During Human–Robot Interaction | International Journal of Social Robotics’. International Journal of Social Robotics (2021) 13:1307–1333. [CrossRef]

- H. Powell and J. Michael, ‘Feeling committed to a robot: why, what, when and how?’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 374, no. 1771, p. 20180039, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. de Haas, P. Vogt, and E. Krahmer, ‘When Preschoolers Interact with an Educational Robot, Does Robot Feedback Influence Engagement?’, Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, vol. 5, no. 12, Art. no. 12, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. T. Valadão et al., ‘Analysis of the use of a robot to improve social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder’, Res. Biomed. Eng., vol. 32, pp. 161–175, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Filippini and A. Merla, ‘Systematic Review of Affective Computing Techniques for Infant Robot Interaction | International Journal of Social Robotics’. International Journal of Social Robotics (2023) 15:393–409. [CrossRef]

- S. Marchesi, D. Ghiglino, F. Ciardo, J. Perez-Osorio, E. Baykara, and A. Wykowska, ‘Do We Adopt the Intentional Stance Toward Humanoid Robots?’, Front. Psychol., vol. 10, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. Rauchbauer, B. Nazarian, M. Bourhis, M. Ochs, L. Prévot, and T. Chaminade, ‘Brain activity during reciprocal social interaction investigated using conversational robots as control condition’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 374, no. 1771, p. 20180033, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Anna, H. Ruud ‘Social Cognition in the Age of Human–Robot Interaction: Trends in Neurosciences’. Volume 43, Issue 6P373-384June 2020.

- S. krystin, S. Virginia, ‘Can a robot teach me that? Children’s ability to imitate robots - ScienceDirect’. Volume 203, March 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).