Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The situation includes some questions such as the native language, cognition of the robot, culture, scenes.

- Objects include who, how, and goal; and

- The role includes gender, bio-sociological, social differentiation, and cultural situation roles.

2. Background

2.1. Communication Strategies with ASD

2.2. Social Robots for ASD

2.3. Emotional Communication

2.4. Social Robot’s Emotional Communication

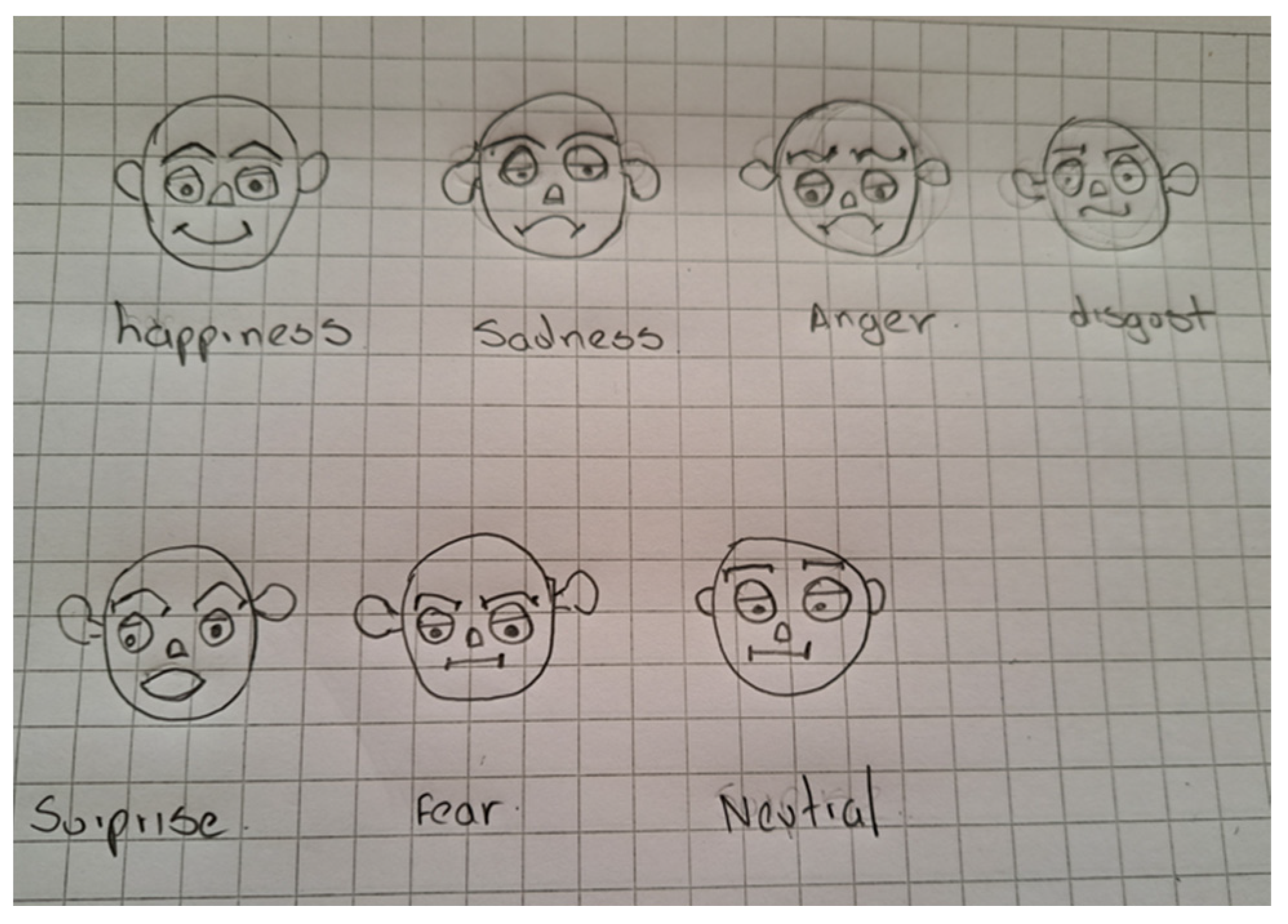

2.4.1. Visual Channel

2.4.2. Hearing Channel

2.4.3. Touch Channel

2.4.4. Physiological Channel

3. Design Path

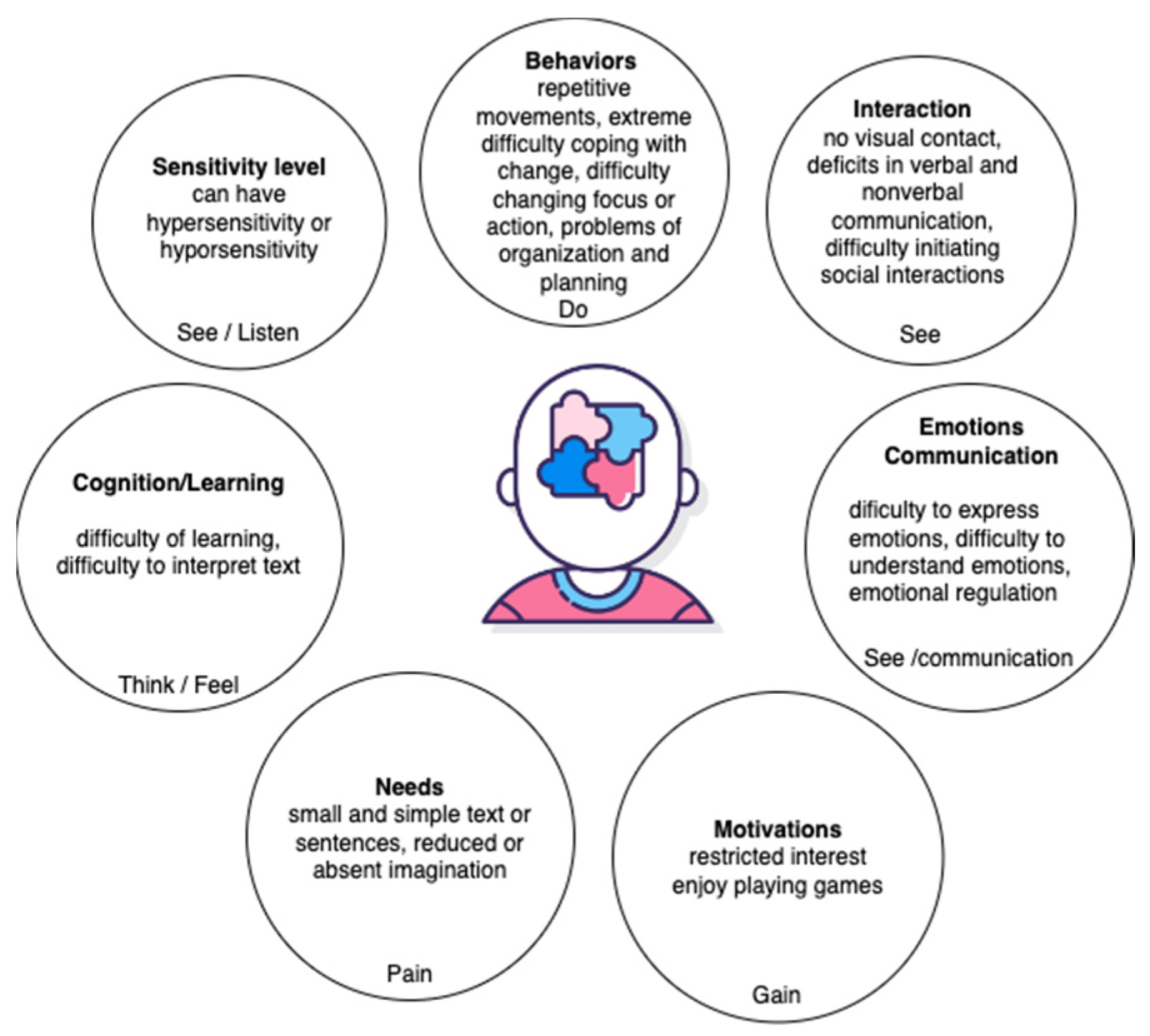

3.1. Analysis

3.2. Ethical Considerations

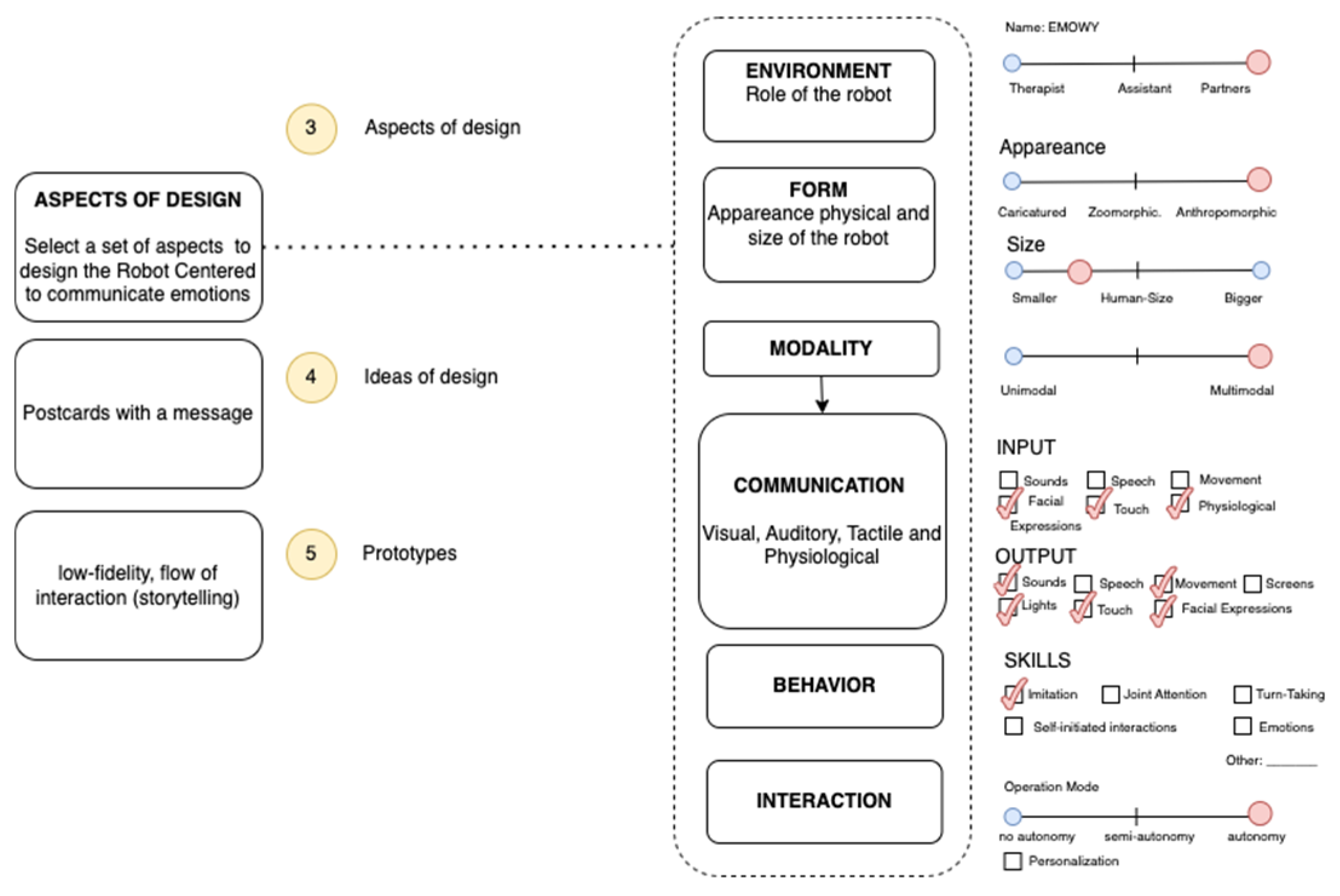

3.3. Aspects of design

- A.

- Environment

- B.

- Form

- C.

- Modality

- D.

- Communication

- E.

- Interaction

- F.

- Behavior

3.4. Ideas of Design

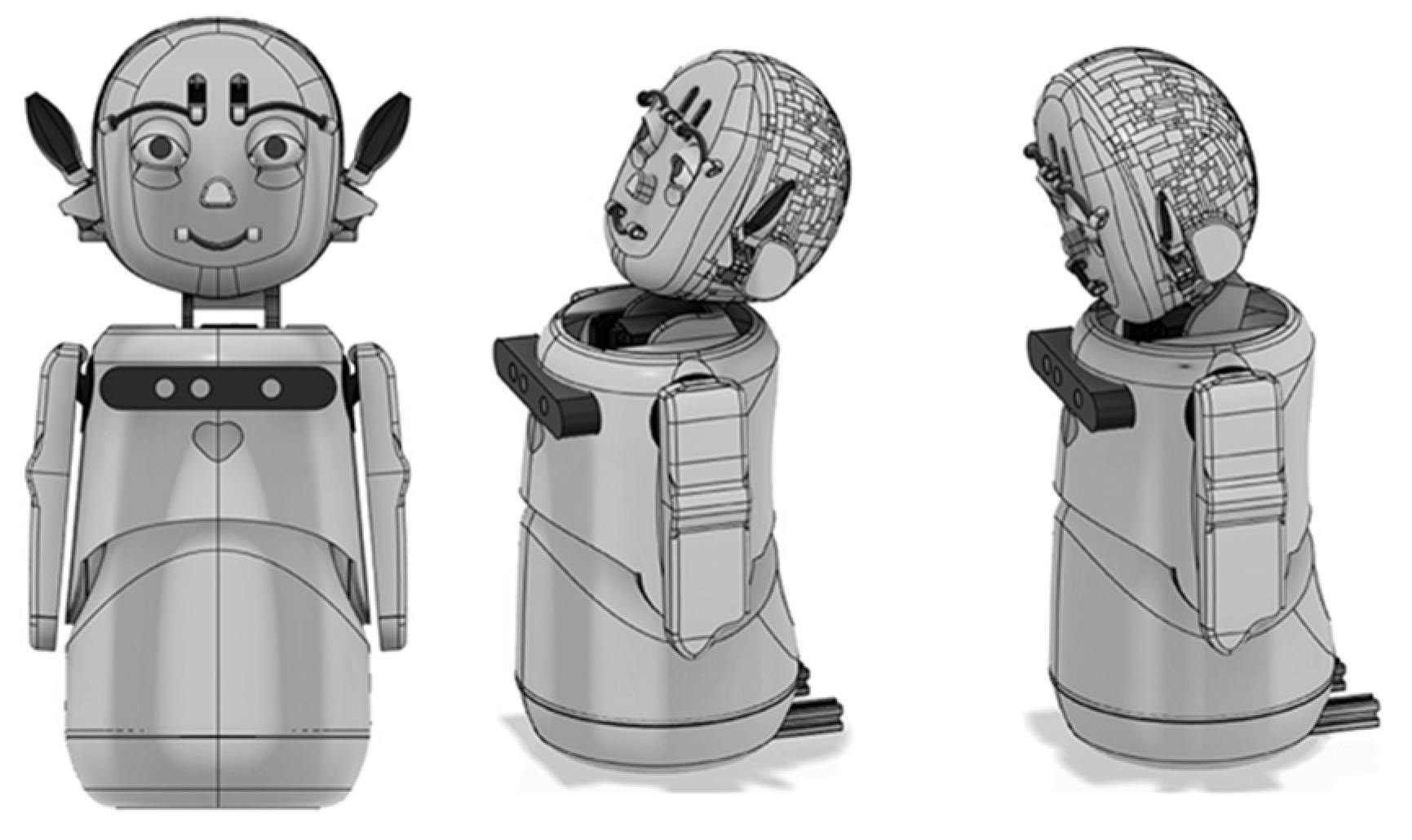

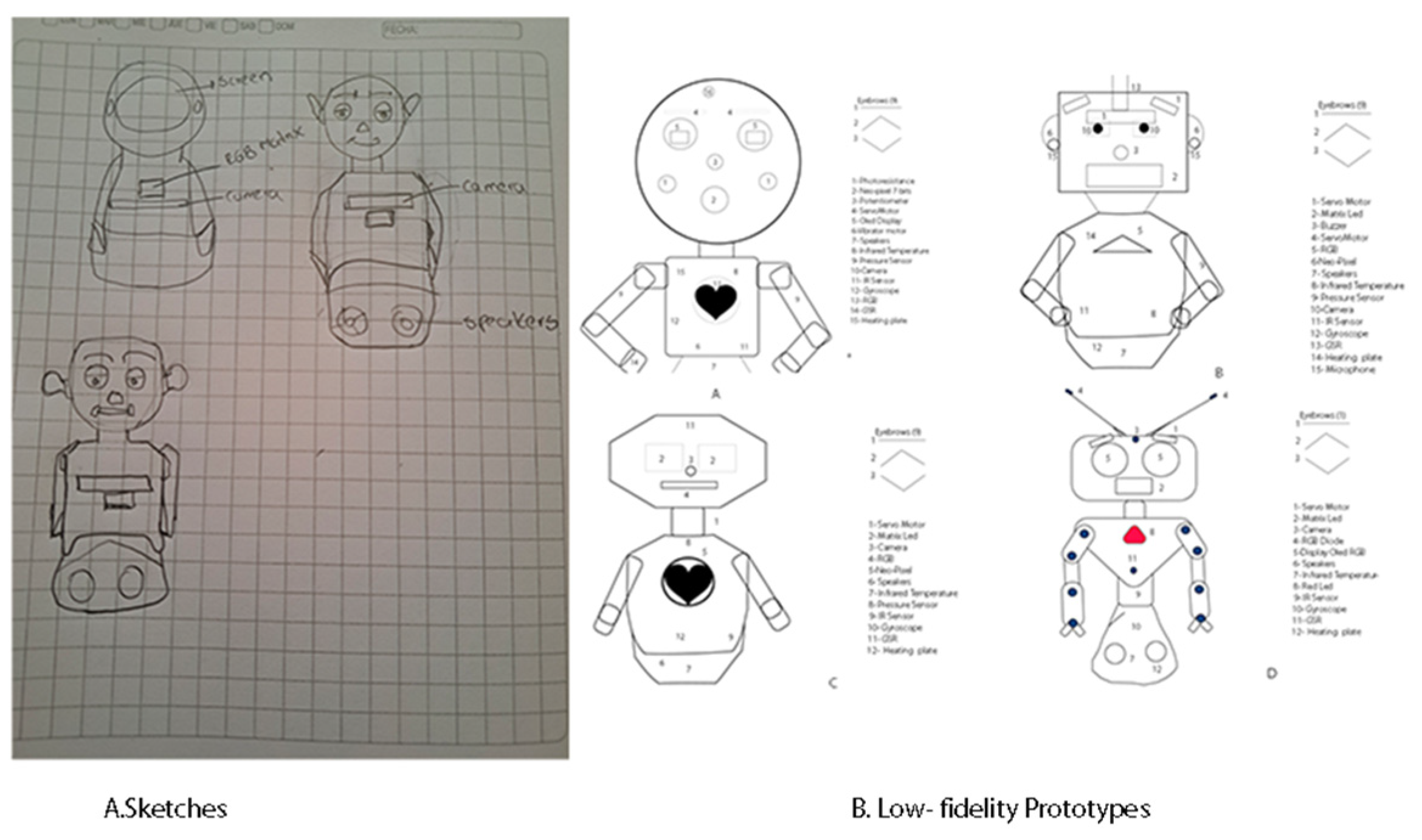

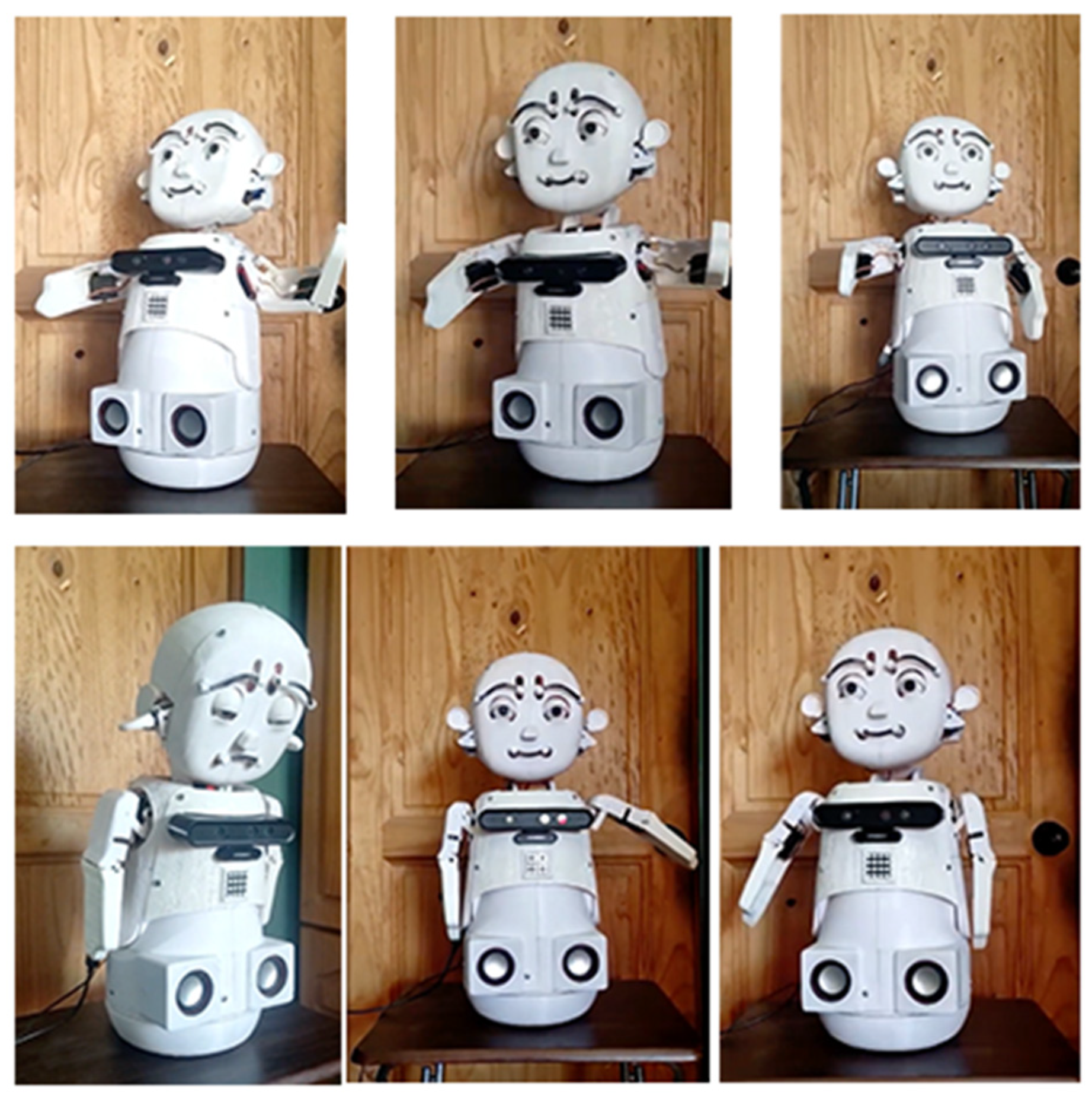

3.5. Prototypes

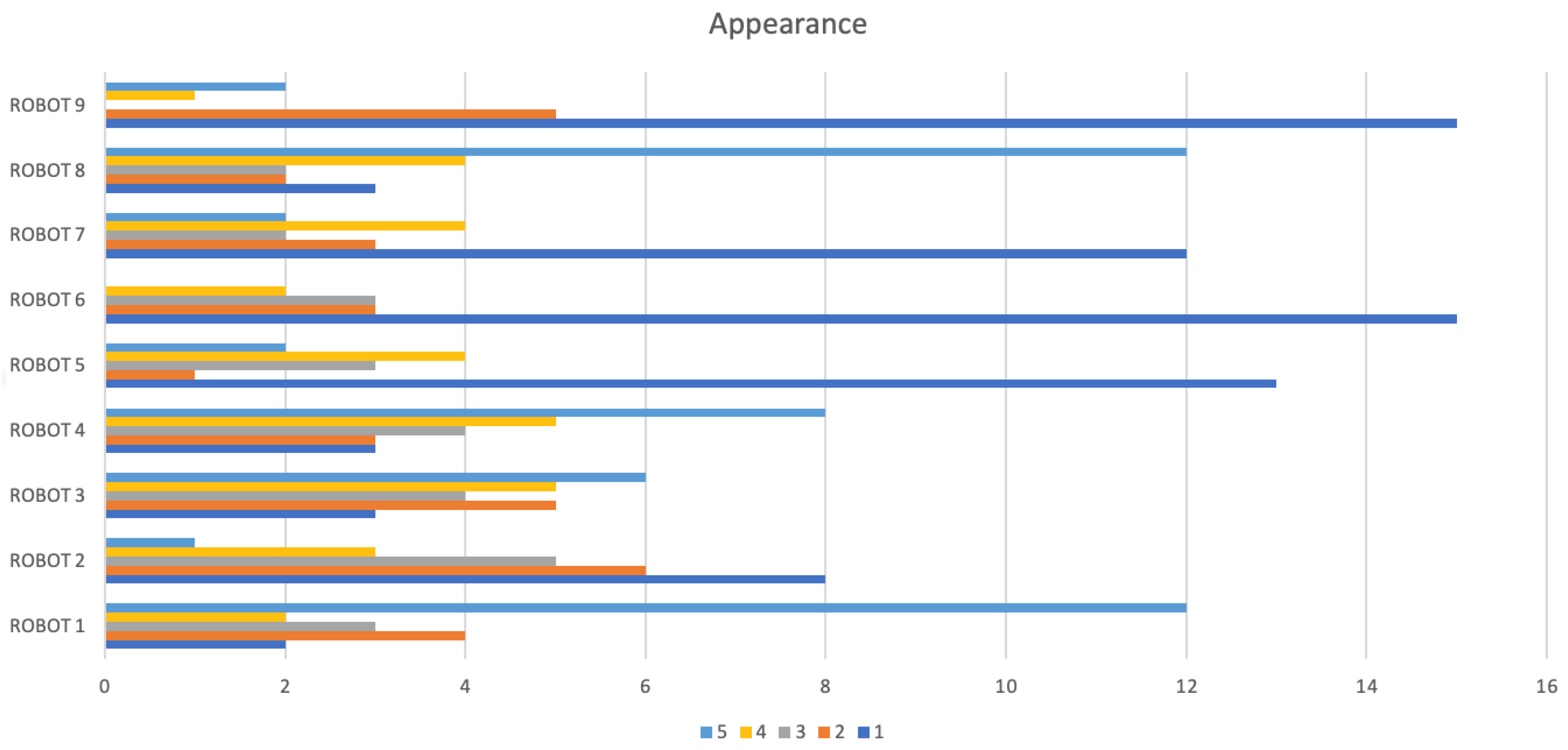

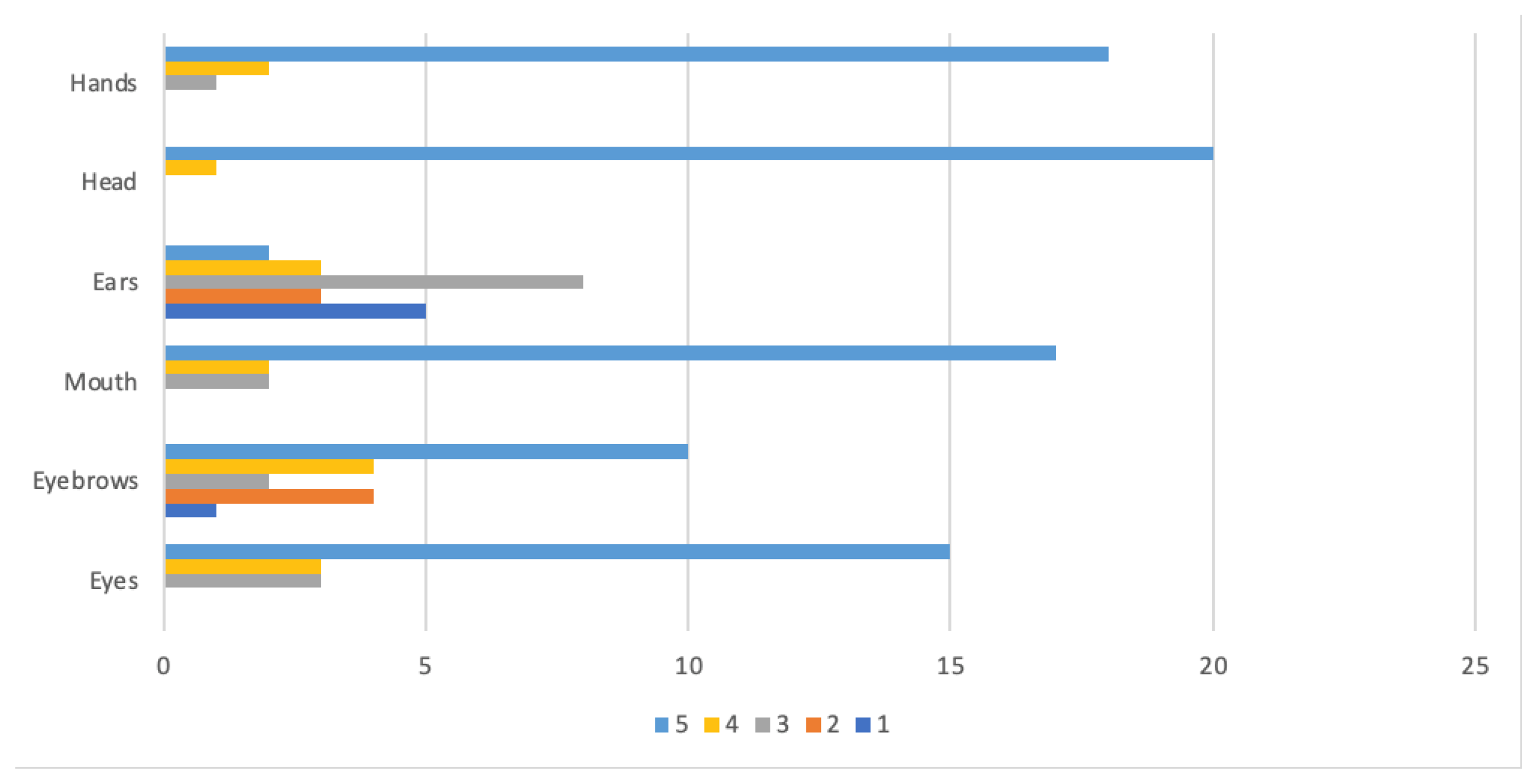

4. Case of Study

4.1. Analysis

- -

- Novelty, interaction with the object, ease of imitation disadvantages preference for the machine and inhibition or poor motivation for interaction with peers or others

- -

- Advantages could be the process of implementing advanced ICTs in these therapies, recognition of new strategies by children and their families. Disadvantages could be poor adaptation of children with ASD and associated visual diagnoses.

- -

- The advantages of having a robot are to be able to have a continuous and specific programming of skills in which it will work and will be constantly exposed through the robot without emotional alterations of a therapist if not specific programming and disadvantages is the issue of predictable environments in a time of crisis in which the least can be pitied with the robot.

- -

- Advantage innovation, disadvantage that they get used to and lose communication with the human being.

- -

- Make gestures approximating to signs for greeting, requesting, pointing.

- -

- The robot should be clear in your tone of voice, movements, or sounds.

- -

- Facial expressions

- -

- Have understandable facial expression, straight posture.

- -

- Imitation of all kinds

- -

- Robotic voice

- -

- Loose or pointed metal parts,

- -

- Loud or unexpected sounds

- -

- Sharp artefacts, loud sounds, loud colours, no glass or transparent panel as it would be distracting and the off button too hidden.

- -

- No robotic verbal language, but a "normal" voice.

| Hardware Aspects | Moxie | Nao | Kaspar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Humanoid | Humanoid | Humanoid |

| Tall | 38.7 cm | 58 cm | 56 cm |

| Genre | - | - | Boy |

| Biped | False | True | False |

| Facial expressions | Using display representing face features such as: eyes, mouth, eyelips | Eyes, Voice | Eyes, Mouth, Eyelips, |

| Open Programming | False | True | True |

| Movements | Head, Torso, Arms, Neck and hands. | Head; Arms; Hand; Pelvis; Legs | Head, Neck, Arms, Torso |

| Servos Total (actuators) | 9 | 25 | 22 |

| Sensors | (4) Microphones, (1) Camera 5MP | OmniVision cameras; Inertial sensor; Sonar range finder; Infrared sensors; Tactile sensors; Pressure sensors;Microphones | Cameras in eyes; force sensors |

| Response multimodal | Voice and visual | Voice, tactile and visual | Visual, Tactile, and voice |

| Language | English | English | English |

4.2. Ethical Considerations

- -

- Robot should have humanoid appearance.

- -

- Emotions express using facial expressions, body expressions and hands.

- -

- The robot should allow to be adjusted the genre and girl robot or boy robot.

- -

- The robot's voice should not be robotized.

- -

- The robot should express basic emotions and some complex such as: pride, empathy, embarrassment.

4.3. Aspects of design

4.4. Ideas of Design

- unaltered robot shape.

- privacy: Only the person who interacts physically with the robot can feel the thermal stimulus.

- if the people who do not interact physically with the robot cannot perceive the thermal stimulus.

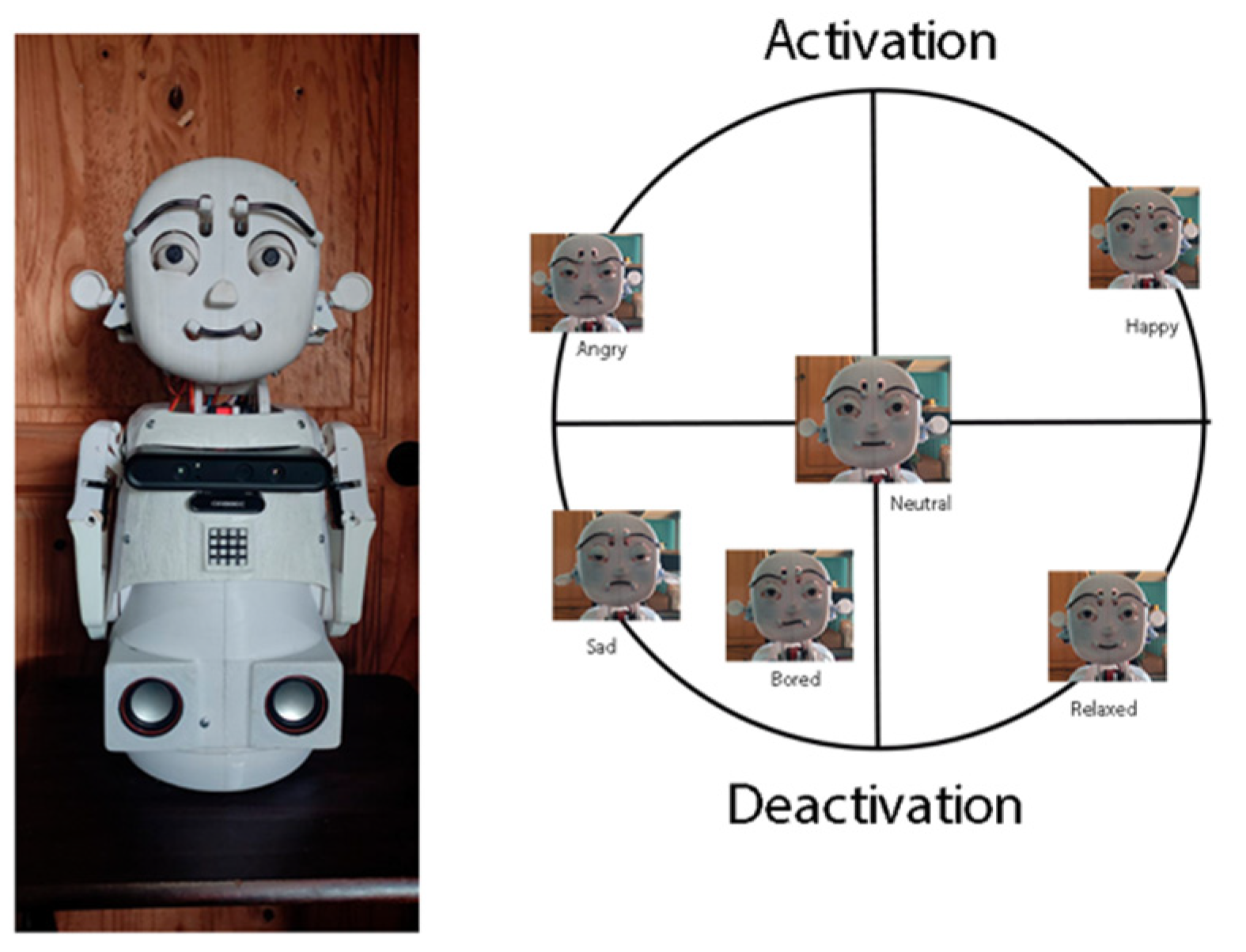

4.5. Prototype

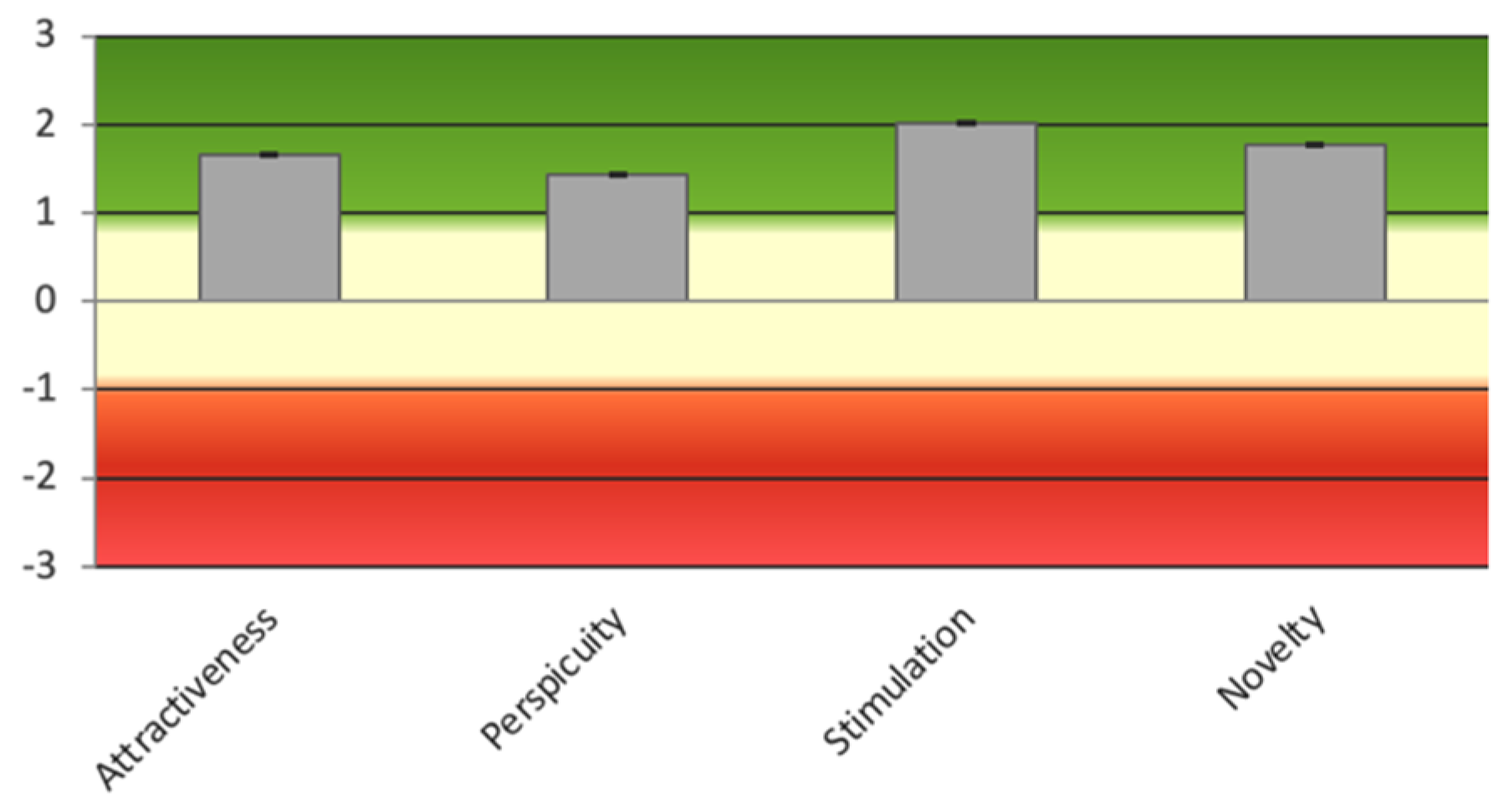

- -

- Attractiveness: the impression of the product

- -

- Perspicuity: Easy to use and follow the product

- -

- Stimulation: how engaging the product is

- -

- Novelty: the novelty of the product

| Attractiveness | 1.652 | 0.23 |

| Perspicuity | 1.434 | 0.11 |

| Stimulation | 2.023 | 0.11 |

| Novelty | 1.773 | 0.23 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed., Washington, DC. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation/World Bank. The World Report on Disability. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011.

- Samadi, S. A., & McConkey, R. (2011). Autism in developing countries: lessons from iran. Autism research and treatment, 2011, 145359. [CrossRef]

- Kirkovski, M., et al.: A review of the role of female gender in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 43(11), 2584–2603 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Robins, B., Dautenhahn, K., Boekhorst, R.T. et al. (2005). Robotic assistants in therapy and education of children with autism: can a small humanoid robot help encourage social interaction skills?. Univ Access Inf Soc 4, 105–120. [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B., Nass, C. (1998). The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Tele- vision, and New Media like Real People and Places. Cambridge University Press (2nd edition).

- Kozima, C. Nakagawa and Y. Yasuda (2005). Interactive robots for communication-care: a case-study in autism therapy, ROMAN 2005. IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 2005., Nashville, TN, USA, 2005, pp. 341-346. [CrossRef]

- Ali S., Mehmood F., Ayaz Y., Asgher U., Khan M.J. (2020) Effect of Different Visual Stimuli on Joint Attention of ASD Children Using NAO Robot. In: Ayaz H. (eds) Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering. AHFE 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 953. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Huijnen, C.A.G.J., Verreussel-Willen, H.A.M.D., Lexis, M.A.S. et al. (2020) Robot KASPAR as Mediator in Making Contact with Children with Autism: A Pilot Study. Int J of Soc Robotics (2020). [CrossRef]

- Nikki Hurst and Caitlyn Clabaugh and Rachel Baynes and Jeff Cohn and Donna Mitroff and Stefan Scherer. Social and Emotional Skills Training with Embodied Moxie, arXiv, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Costa et al., "More Attention and Less Repetitive and Stereotyped Behaviors using a Robot with Children with Autism," 2018 27th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 2018, pp. 534-539. [CrossRef]

- C. M. Stanton, P. H. Kahn Jr, R. L. Severson, J. H. Ruckert, and B. T. Gill. (2008). Robotic animals might aid in the social development of children with autism. in HRI ’08: Proceedings of the 3rd ACM/IEEE international conference on Human robot interaction, 2008, pp. 271–278. [CrossRef]

- Kunold, L.; Onnasch, L. A Framework to Study and Design Communication with Social Robots. Robotics 2022, 11, 129. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., Ge, S.S. (2017). Role-Oriented Designing: A Methodology to Designing for Appearance and Interaction Ways of Customized Professional Social Robots. In: , et al. Social Robotics. ICSR 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10652. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- C. Bartneck and J. Forlizzi, "A design-centred framework for social human-robot interaction," RO-MAN 2004. 13th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (IEEE Catalog No.04TH8759), Kurashiki, Japan, 2004, pp. 591-594. [CrossRef]

- Minja Axelsson, Raquel Oliveira, Mattia Racca, and Ville Kyrki. 2021. Social Robot Co-Design Canvases: A Participatory Design Framework. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 11, 1, Article 3 (March 2022), 39 pages. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Duque, A.A., Aycardi, L.F., Villa, A. et al. Collaborative and Inclusive Process with the Autism Community: A Case Study in Colombia About Social Robot Design. Int J of Soc Robotics 13, 153–167 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Belpaeme, T., Vogt, P., van den Berghe, R. et al. Guidelines for Designing Social Robots as Second Language Tutors. Int J of Soc Robotics 10, 325–341 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Hannah Louise Bradwell, Gabriel E. Aguiar Noury, Katie Jane Edwards, Rhona Winnington, Serge Thill, Ray B. Jones. Design recommendations for socially assistive robots for health and social care based on a large-scale analysis of stakeholder positions: Social robot design recommendations, Health Policy and Technology, vol 10 (3), 2021, 100544, ISSN 2211-8837. [CrossRef]

- Field T., Nadel Jacqueline and Ezell Shauna. (2011). Imitation Therapy for Young Children with Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorders - From Genes to Environment, Tim Williams, IntechOpen. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/autism-spectrum-disorders-from-genes-to-environment/imitation-therapy-for-young-children-with-autism. [CrossRef]

- Charman Tony (2008). Why is joint attention a pivotal skill in autism? Phil trans R. Soc, 358, 315-324, 2003. Michael A. Goodrich and Alan C. Schultz (2008), "Human–Robot Interaction: A Survey", Foundations and Trends® in Human–Computer Interaction: Vol. 1: No. 3, pp 203-275. [CrossRef]

- Holler, J., Kendrick, K.H., Casillas, M., Levinson. (2015). S.C.: Editorial: turn-taking in human communicative interaction. Front. Psychol. 6(DEC), 1–4, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S., Golan, O., & Ashwin, E. (2009). Can emotion recognition be taught to children with autism spectrum conditions? Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 364(1535), 3567–3574. [CrossRef]

- Breazeal, C. (2002). Designing Sociable Machines. In: Dautenhahn, K., Bond, A., Cañamero, L., Edmonds, B. (eds) Socially Intelligent Agents. Multiagent Systems, Artificial Societies, and Simulated Organizations, vol 3. Springer, Boston, MA. [CrossRef]

- Breazeal, C. (2000), "Sociable Machines: Expressive Social Exchange Between Humans and Robots". Sc.D. dissertation, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, MIT.

- Kerstin Dautenhahn. Robots as social actors: Aurora and the case of autism In Proceedings of the Third Cognitive Technology Conference, 1999.

- Billard A (2003) Robota: clever toy and educational tool. Robot Autonom Syst 42(3–4):259. [CrossRef]

- Kozima H, Nakagawa C, Kawai N, Kosugi D, Yano Y (2004) A humanoid in company with children. In: 4th IEEE/RAS international conference on humanoid robots, 2004., (IEEE, 2004), vol 1, pp 470–477. [CrossRef]

- Dautenhahn K, Nehaniv CL, Walters ML, Robins B, Kose-Bagci H, Mirza NA, Blow M (2009) KASPAR - a minimally expressive humanoid robot for human-robot interaction research. Appl Bionics Biomech 6(3–4):369. [CrossRef]

- Hideki Kozima and Marek Piotr Michalowski and Cocoro Nakagawa. Keepon: A playful robot for research, therapy, and entertainment. International Journal of Social Robotics, 2009. [CrossRef]

- https://leka.io, (accessed on 04 August 2021).

- A. P. Costa et al., "More Attention and Less Repetitive and Stereotyped Behaviors using a Robot with Children with Autism," 2018 27th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 2018, pp. 534-539. [CrossRef]

- Gregoire Milliez. 2018. Buddy: A Companion Robot for the Whole Family. In <i>Companion of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction</i> (<i>HRI '18</i>). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 40. [CrossRef]

- Casas-Bocanegra, D.; Gomez-Vargas, D.; Pinto-Bernal, M.J.; Maldonado, J.; Munera, M.; Villa-Moreno, A.; Stoelen, M.F.; Belpaeme, T.; Cifuentes, C.A. An Open-Source Social Robot Based on Compliant Soft Robotics for Therapy with Children with ASD. Actuators 2020, 9, 91. [CrossRef]

- Nikki Hurst and Caitlyn Clabaugh and Rachel Baynes and Jeff Cohn and Donna Mitroff and Stefan Scherer. Social and Emotional Skills Training with Embodied Moxie, arXiv, 2020.

- Moerman, C. J., & Jansens, R. M. (2020). Using social robot PLEO to enhance the well-being of hospitalised children. Journal of Child Health Care. [CrossRef]

- Aubrey Shick. 2013. Romibo robot project: an open-source effort to develop a low-cost sensory adaptable robot for special needs therapy and education. In <i>ACM SIGGRAPH 2013 Studio Talks</i> (<i>SIGGRAPH '13</i>). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 16, 1. [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, Anne; and Hübner, Susanne. "Towards a Theory of Emotional Communication." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 7.4 (2005):. [CrossRef]

- Reis, H. T., & Sprecher, S. (Eds.) (2009). Encyclopedia of human relationships. SAGE Publications, Inc.. [CrossRef]

- aantje Derks, Agneta H. Fischer, Arjan E.R. Bos. The role of emotion in computer-mediated communication: A review, Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 24, Issue 3, 2008, Pages 766-785, ISSN 0747-5632. [CrossRef]

- William James. What is an Emotion?. Mind, Vol os-IX, Issue 34, 1 April 1884, Pages 188-205. [CrossRef]

- Schachter, S., & Singer, J. (1962). Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychological Review, 69(5), 379–399. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, B. (1975). Walter B. Cannon: Personal reminiscences. In Brooks, C. McC., Koizumi, K., Pinkston, J. O. (Eds.), The life and contributions of Walter Bradford Cannon 1871–1945: His influence on the development of physiology in the twentieth century (pp. 151–169). New York: State University of New York.

- Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Grosset/Putnam.

- C. E. Shannon, "A mathematical theory of communication," in The Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379-423, July 1948. [CrossRef]

- Lasswell, H.D. The Structure and Function of Communication in Society. Commun. Ideas 1948, 37, 136–139.

- M. Val-Calvo, J. R. Álvarez-Sánchez, J. M. Ferrández-Vicente and E. Fernández, "Affective Robot Story-Telling Human-Robot Interaction: Exploratory Real-Time Emotion Estimation Analysis Using Facial Expressions and Physiological Signals," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 134051-134066, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Robertson CE, Baron-Cohen S. Sensory perception in autism. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:671–684. [CrossRef]

- Bonarini, A. Communication in Human-Robot Interaction. Curr Robot Rep 1, 279–285 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hiromi Kobayashi, Shiro Kohshima. Unique morphology of the human eye and its adaptive meaning: comparative studies on external morphology of the primate eyes. Journal of Human Evolution, Vol 40 (5), 2001. [CrossRef]

- Florentina Adăscăliţei, Ioan Doroftei. Expressing Emotions in Social Robotics - A Schematic Overview Concerning the Mechatronics Aspects and Design Concepts, IFAC Proceedings Vol 45 (6), 2012, pp 823-828. [CrossRef]

- Barakova, E. I., Bajracharya, P., Willemsen, M., Lourens, T., & Huskens, B. (2015). Long-term LEGO therapy with humanoid robot for children with ASD. Expert Systems: International Journal of Knowledge Engineering and Neural Networks, 32(6), 698–709. [CrossRef]

- Lupis, S. B., Lerman, M., & Wolf, J. M. (2014). Anger responses to psychosocial stress predict heart rate and cortisol stress responses in men but not women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 49, 84–95. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T. Cincarek, H. Kawanami, H. Saruwatari, K. Shikano, and A. Lee, “Voice activity detection applied to hands-free spoken dialogue robot based on decoding using acoustic and language model,” in Proceedings of the 1st international conference on Robot communication and coordination. IEEE Press, 2007, pp. 180–187. [CrossRef]

- Cheng G, Dean-Leon E, Bergner F, Olvera JRG, Leboutet Q, Mittendorfer P. A comprehensive realization of robot skin: sensors, sensing, control, and applications. Proc IEEE. 2019;107(10):2034– 51. [CrossRef]

- Ioannou S., Gallese V., Merla A. (2014). Thermal infrared imaging in psychophysiology: potentialities and limits. Psychophysiology 51, 951–963. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li, O. Kroemer, Z. Su, F. F. Veiga, M. Kaboli and H. J. Ritter, "A Review of Tactile Information: Perception and Action Through Touch," in IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 1619-1634, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. D. and P. K. Khosla (1991). "Using tactile data for real-time feedback." The International Journal of Robotics Research 10(2): 88-102. [CrossRef]

- Bonarini A, Garzotto F, Gelsomini M, Romero M, Clasadonte F, Yilmaz ANÇ. A huggable, mobile robot for developmental disorder interventions in a multi-modal interaction space. In: Proceedings of the 25th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN 2016). New York: IEEE Computer Press; 2016. p. 823–30. [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad AY, Cabibihan J-J, Bonarini A. Influence of reaction time in the emotional response of a companion robot to a child’s aggressive interaction. Int J Soc Robot. 2020:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.N.; Drougard, N.; Gateau, T.; Dehais, F.; Chanel, C.P.C. How Can Physiological Computing Benefit Human-Robot Interaction? Robotics 2020, 9, 100. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Luo, Shu-Ruei Chang, Chien-Chieh Huang and Yee-Pien Yang, "Human robot interactions using speech synthesis and recognition with lip synchronization," IECON 2011 - 37th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Melbourne, VIC, 2011, pp. 171-176. [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum J, Kyng M, editors. Deisgn at Work- Cooperative design of Computer Systems. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ, USA; 1991.

- Huijnen, C.A.G.J., Lexis, M.A.S., Jansens, R. et al. How to Implement Robots in Interventions for Children with Autism? A Co-creation Study Involving People with Autism, Parents and Professionals. J Autism Dev Disord 47, 3079–3096 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Áurea Hiléia Da Silva Melo, Luis Rivero, Jonathas Silva dos Santos, and Raimundo da Silva Barreto. 2020. EmpathyAut: an empathy map for people with autism. In <i>Proceedings of the 19th Brazilian Symposium on Human Factors in Computing Systems</i> (<i>IHC '20</i>). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 45, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, A.; Caprì, T.; Pignolo, L.; Gismondo, S.; Chilà, P.; Minutoli, R.; Marino, F.; Failla, C.; Arnao, A.A.; Tartarisco, G.; Cerasa, A.; Pioggia, G. Social Humanoid Robots for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review of Modalities, Indications, and Pitfalls. Children 2022, 9, 953. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K., Kumar, M., Fosch-Villaronga, E. et al. Ethical Considerations from Child-Robot Interactions in Under-Resourced Communities. Int J of Soc Robotics (2022). [CrossRef]

- Batya Friedman, Peter H. Kahn, and Alan Borning. 2008. Value sensitive design and information systems. In The Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics, 69–101.

- Qbilat, M.; Iglesias, A.; Belpaeme, T. A Proposal of Accessibility Guidelines for Human-Robot Interaction. Electronics 2021, 10, 561. [CrossRef]

- Shah A, Frith U. An islet of ability in autistic children: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1983;24:613–620. [CrossRef]

- Cabibihan, JJ., Javed, H., Ang, M. et al. Why Robots? A Survey on the Roles and Benefits of Social Robots in the Therapy of Children with Autism. Int J of Soc Robotics 5, 593–618 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Leila Takayama and Caroline Pantofaru. 2009. Influences on proxemic behaviors in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. IEEE, 5495–5502. [CrossRef]

- Christoph Bartneck and Jodi Forlizzi. 2004. A design-centred framework for social human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN’04). IEEE, 591–594. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V.; O’Sullivan, M.; Chan, A.; Diacoyanni-Tarlatzis, I.; Heider, K.; Krause, R.; Lecompte, W.A.; Pitcairn, T.; Ricci-Bitti, P.E.; et al. Universals and cultural differences in the judgments of facial expressions of emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 712–717. [CrossRef]

- Graham Wilson, Dobromir Dobrev, and Stephen A. Brewster. 2016. Hot under the collar: Mapping thermal feedback to dimensional models of emotion. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 4838–4849. [CrossRef]

- Schrepp, M., Hinderks, A. y Thomaschewski, J. (2017). Design and Evaluation of a Short Version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S). International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 4 (6), 103-108. [CrossRef]

- Robins B, Otero N, Ferrari E, Dautenhahn K (2007) Eliciting requirements for a robotic toy for children with autism—results from user panels. In: Proc of the 16th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN), pp 101–106. [CrossRef]

- Michaud F, Duquette A, Nadeau I (2003) Characteristics of mobile robotic toys for children with pervasive developmental disorders. In: Proc of the IEEE international conference on systems, man and cybernetics, pp 2938–2943. [CrossRef]

- Kozima H, Nakagawa C, Yasuda Y (2007) Children–robot interaction: a pilot study in autism therapy. Prog Brain Res 164:385. [CrossRef]

- Zabala, U.; Rodriguez, I.; Martínez-Otzeta, J.M.; Lazkano, E. Expressing Robot Personality through Talking Body Language. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4639. [CrossRef]

- Michaud F, Larouche H, Larose F, Salter T, Duquette A, Mercier H, Lauria M (2007) Mobile robots engaging children in learning. In: Proc of the Canadian medical and biological engineering conference.

- Norman, D.A.: Emotional design. Basic Books, New York (2004).

| Attractiveness | 1.65 |

| Pragmatic Quality | 1.23 |

| Hedonic Quality | 1.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).