Submitted:

09 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

One of the main threats for the survival of the Iberian lynx are infectious diseases. Feline parvo-viruses cause an often fatal disease in cats and have been isolated from different species of Felidae and other carnivores. The present study is the first description of a parvoviral sequence isolated from the brain of an Iberian lynx which had died four weeks after been transferred to a quarantine centre from a hunting estate in Castilla-La-Mancha (southern border of the Iberian plateau). Four days prior to death he had developed anorexia and muscle weakness. The nucleotide sequence, 4,589 nt long (GenBank PP781551), was most proximal to that isolated from a Eurasian badger in Italy but showed also great homology with others from cats and other carnivores isolated in Spain and Italy, including that from a cat sequenced by us to elucidate the origin of the infection, which has not been clarified. The phylogenetic analysis of the capsid protein, VP2, which determines tropism and host range, confirmed that the lynx sequence was most proximal to feline than to canine parvoviruses, and was thus classified as Protoparvovirus carnivoran 1. More studies, in-cluding serology, are needed to understand the pathogenesis of this infection.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Report

2.2. Samples

2.3. DNA Extraction

2.4. Commercial End-Point PCR

2.5. Inhouse Nested PCR

2.6. Sequencing and Further Analyses

2.7. Serological Analysis

3. Results

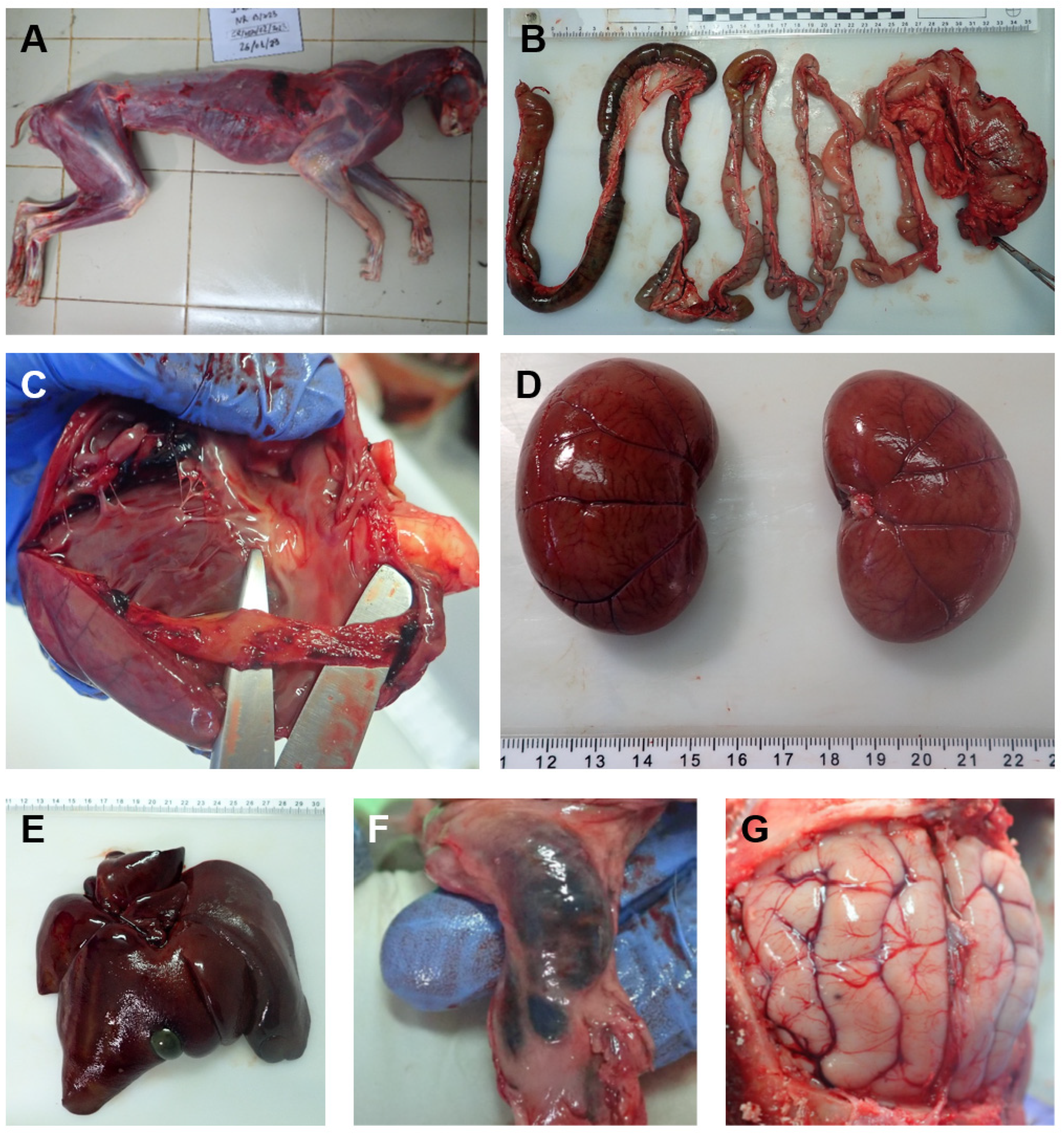

3.1. Necropsy Findings of the Affected Iberian Lynx

3.2. Prevalence of Parvovirus in the Hunting Estate

3.3. Parvoviral Sequences in a Cat and a Dog in Spain

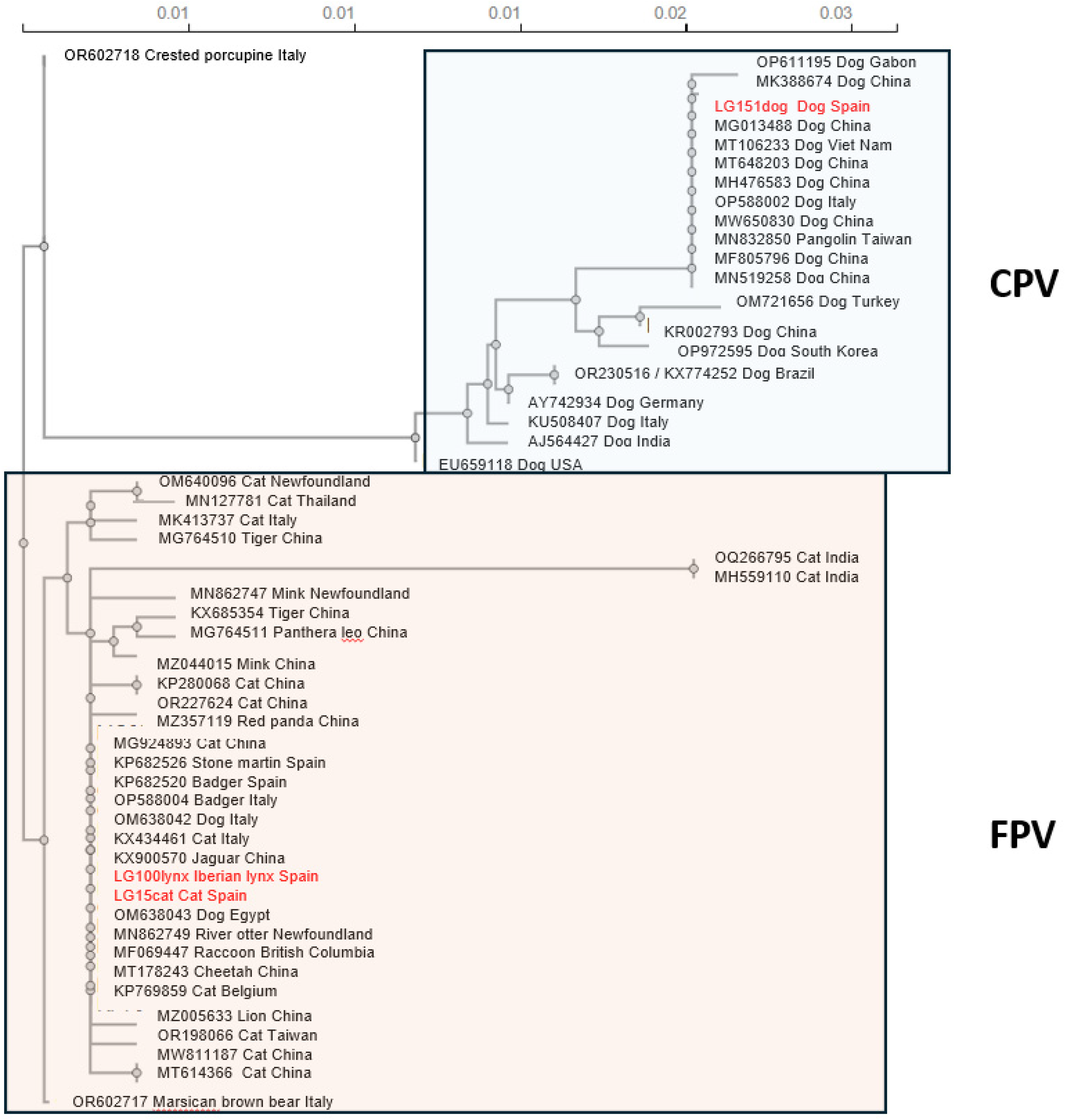

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of VP2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IUCN Recovery of the Iberian Lynx: A Conservation Success in Spain 2024.

- Spanish MInistry of Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge Fauna de Vertebrados: Mamíferos) (Fauna of Vertebrates: Mammals).

- Duarte, A.; Fernandes, M.; Santos, N.; Tavares, L. Virological Survey in Free-Ranging Wildcats (Felis Silvestris) and Feral Domestic Cats in Portugal. Vet. Microbiol. 2012, 158, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasieri, J.; Schmiedeknecht, G.; Förster, C.; König, M.; Reinacher, M. Parvovirus Infection in a Eurasian Lynx (Lynx Lynx) and in a European Wildcat (Felis Silvestris Silvestris). J. Comp. Pathol. 2009, 140, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millán, J.; Candela, M.G.; Palomares, F.; Cubero, M.J.; Rodríguez, A.; Barral, M.; de la Fuente, J.; Almería, S.; León-Vizcaíno, L. Disease Threats to the Endangered Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus). Vet. J. 2009, 182, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roelke, M.E.; Johnson, W.E.; Millán, J.; Palomares, F.; Revilla, E.; Rodríguez, A.; Calzada, J.; Ferreras, P.; León-Vizcaíno, L.; Delibes, M.; et al. Exposure to Disease Agents in the Endangered Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus). Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, G.; López-Parra, M.; Garrote, G.; Fernández, L.; Del Rey-Wamba, T.; Arenas-Rojas, R.; García-Tardío, M.; Ruiz, G.; Zorrilla, I.; Moral, M.; et al. Evaluating Mortality Rates and Causalities in a Critically Endangered Felid across Its Whole Distribution Range. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera, F.; Grande-Gómez, R.; Peña, J.; Vázquez, A.; Palacios, M.J.; Rueda, C.; Corona-Bravo, A.I.; Zorrilla, I.; Revuelta, L.; Gil-Molino, M.; et al. Disease Surveillance during the Reintroduction of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus) in Southwestern Spain. Animals 2021, 11, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña, L.; Garcia, P.; Jiménez, M.Á.; Benito, A.; Alenza, M.D.P.; Sánchez, B. Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings in Lymphoid Tissues of the Endangered Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus). Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2006, 29, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.; Candela, M.G.; Palomares, F.; Cubero, M.J.; Rodríguez, A.; Barral, M.; de la Fuente, J.; Almería, S.; León-Vizcaíno, L. Disease Threats to the Endangered Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus). Vet. J. 2009, 182, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrs, V.R. Feline Panleukopenia: A Re-Emergent Disease. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2019, 49, 651–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiza, C.K.; De Lahunta, A.; Scott, F.W.; Gillespie, J.H. Pathogenesis of Feline Panleukopenia Virus in Susceptible Newborn Kittens II. Pathology and Immunofluorescence. Infect. Immun. 1971, 3, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotmore, S.F.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Canuti, M.; Chiorini, J.A.; Eis-Hubinger, A.-M.; Hughes, J.; Mietzsch, M.; Modha, S.; Ogliastro, M.; Pénzes, J.J.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Parvoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.-C.; Kim, S.-J.; Nguyen, V.G.; Shin, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Lim, S.-K.; Park, Y.H.; Park, B. New Genotype Classification and Molecular Characterization of Canine and Feline Parvoviruses. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 21, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotmore, S.F.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Chiorini, J.A.; Mukha, D.V.; Pintel, D.J.; Qiu, J.; Soderlund-Venermo, M.; Tattersall, P.; Tijssen, P.; Gatherer, D.; et al. The Family Parvoviridae. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, R.; Calleros, L.; Marandino, A.; Sarute, N.; Iraola, G.; Grecco, S.; Blanc, H.; Vignuzzi, M.; Isakov, O.; Shomron, N.; et al. Phylogenetic and Genome-Wide Deep-Sequencing Analyses of Canine Parvovirus Reveal Co-Infection with Field Variants and Emergence of a Recent Recombinant Strain. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Doménech, A.; Gomez-Lucia, E.; Méndez, J.L.; Ortiz, J.C.; Benítez, L. A Novel Dependoparvovirus Identified in Cloacal Swabs of Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta Monachus) from Urban Areas of Spain. Viruses 2023, 15, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinel, A.; Parrish, C.R.; Bloom, M.E.; Truyen, U. Parvovirus Infections in Wild Carnivores. J. Wildl. Dis. 2001, 37, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuetzer, B.; Hartmann, K. Feline Parvovirus Infection and Associated Diseases. Vet. J. 2014, 201, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capozza, P.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C.; Decaro, N. Emerging Parvoviruses in Domestic Cats. Viruses 2021, 13, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calatayud, O.; Esperón, F.; Velarde, R.; Oleaga, Á.; Llaneza, L.; Ribas, A.; Negre, N.; de la Torre, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Millán, J. Genetic Characterization of Carnivore Parvoviruses in Spanish Wildlife Reveals Domestic Dog and Cat-Related Sequences. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, A.B.; Kohler, D.J.; Fox, K.A.; Brown, J.D.; Gerhold, R.W.; Shearn-Bochsler, V.I.; Dubovi, E.J.; Parrish, C.R.; Holmes, E.C. Frequent Cross-Species Transmission of Parvoviruses among Diverse Carnivore Hosts. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2342–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopardi, S.; Milani, A.; Cocchi, M.; Bregoli, M.; Schivo, A.; Leardini, S.; Festa, F.; Pastori, A.; de Zan, G.; Gobbo, F.; et al. Carnivore Protoparvovirus 1 (CPV-2 and FPV) Circulating in Wild Carnivores and in Puppies Illegally Imported into North-Eastern Italy. Viruses 2022, 14, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, Y.-G.; Kim, H.-R.; Park, J.; Kim, J.-M.; Shin, Y.-K.; Lee, K.-K.; Kwon, O.-K.; Jeoung, H.-Y.; Kang, H.-E.; Ku, B.-K.; et al. Epidemiological and Molecular Approaches for a Fatal Feline Panleukopenia Virus Infection of Captive Siberian Tigers (Panthera Tigris Altaica) in the Republic of Korea. Animals 2023, 13, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacristán, I.; Esperón, F.; Pérez, R.; Acuña, F.; Aguilar, E.; García, S.; López, M.J.; Neves, E.; Cabello, J.; Hidalgo-Hermoso, E.; et al. Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Carnivore Protoparvovirus-1 Infection in the Wild Felid Leopardus Guigna in Chile. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 3335–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, C.R. Emergence, Natural History, and Variation of Canine, Mink, and Feline Parvoviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 1990, 38, 403–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolangath, S.M.; Upadhye, S.V.; Dhoot, V.M.; Pawshe, M.D.; Bhadane, B.K.; Gawande, A.P.; Kolangath, R.M. Molecular Investigation of Feline Panleukopenia in an Endangered Leopard (Panthera Pardus) – a Case Report. BMC Vet. Res. 2023, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, C.I.; García-Bocanegra, I.; McCain, E.; Rodríguez, E.; Zorrilla, I.; Gómez, A.M.; Ruiz, C.; Molina, I.; Gómez-Guillamón, F. Prevalence of Selected Pathogens in Small Carnivores in Reintroduction Areas of the Iberian Lynx ( Lynx Pardinus ). Vet. Rec. 2017, 180, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.; Santos, N.; Parrish, C.; Thompson, G. Genetic Characterization of Canine Parvovirus in Sympatric Free-Ranging Wild Carnivores in Portugal. J. Wildl. Dis. 2017, 53, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.D.; Henriques, A.M.; Barros, S.C.; Fagulha, T.; Mendonça, P.; Carvalho, P.; Monteiro, M.; Fevereiro, M.; Basto, M.P.; Rosalino, L.M.; et al. Snapshot of Viral Infections in Wild Carnivores Reveals Ubiquity of Parvovirus and Susceptibility of Egyptian Mongoose to Feline Panleukopenia Virus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nájera, F.; Grande-Gómez, R.; Peña, J.; Vázquez, A.; Palacios, M.J.; Rueda, C.; Corona-Bravo, A.I.; Zorrilla, I.; Revuelta, L.; Gil-Molino, M.; et al. Disease Surveillance during the Reintroduction of the Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus) in Southwestern Spain. Animals 2021, 11, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupo de Manejo Sanitario del Lince Ibérico Manual Sanitario Del Lince Ibérico. 2014. Available online: https://Www.Lynxexsitu.Es/Ficheros/Documentos_pdf/85/Manual_Sanitario_Lince_Ib_2014.Pdf.

- Söding, J. Protein Homology Detection by HMM–HMM Comparison. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, G.; López-Parra, M.; Garrote, G.; Fernández, L.; Del Rey-Wamba, T.; Arenas-Rojas, R.; García-Tardío, M.; Ruiz, G.; Zorrilla, I.; Moral, M.; et al. Evaluating Mortality Rates and Causalities in a Critically Endangered Felid across Its Whole Distribution Range. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryser-Degiorgis, M.-P.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Leutenegger, C.M.; af Segerstad, C.H.; Mörner, T.; Mattsson, R.; Lutz, H. Epizootiologic Investigations of Selected Infectious Disease Agents in Free-Ranging Eurasian Lynx from Sweden. J. Wildl. Dis. 2005, 41, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meli, M.L.; Cattori, V.; Martínez, F.; López, G.; Vargas, A.; Simón, M.A.; Zorrilla, I.; Muñoz, A.; Palomares, F.; López-Bao, J.V.; et al. Feline Leukemia Virus and Other Pathogens as Important Threats to the Survival of the Critically Endangered Iberian Lynx (Lynx Pardinus). PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrish, C.R. Chapter 12. Parvoviridae. In Fenner’s Veterinary Virology; 2016; ISBN 978-0-12-800946-8. [Google Scholar]

- Steinel, A.; Parrish, C.R.; Bloom, M.E.; Truyen, U. Parvovirus Infections in Wild Carnivores. J. Wildl. Dis. 2001, 37, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Desario, C.; Campolo, M.; Lorusso, E.; Colaianni, M.L.; Lorusso, A.; Buonavoglia, C. Tissue Distribution of the Antigenic Variants of Canine Parvovirus Type 2 in Dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 121, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, C.R.; Aquadro, C.F.; Strassheim, M.L.; Evermann, J.F.; Sgro, J.Y.; Mohammed, H.O. Rapid Antigenic-Type Replacement and DNA Sequence Evolution of Canine Parvovirus. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 6544–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Url, A.; Truyen, U.; Rebel-Bauder, B.; Weissenböck, H.; Schmidt, P. Evidence of Parvovirus Replication in Cerebral Neurons of Cats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 3801–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garigliany, M.; Jolly, S.; Dive, M.; Bayrou, C.; Berthemin, S.; Robin, P.; Godenir, R.; Petry, J.; Dahout, S.; Cassart, D.; et al. Risk Factors and Effect of Selective Removal on Retroviral Infections Prevalence in Belgian Stray Cats. Vet. Rec. 2016, 178, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Posthaus, H.; Breitenmoser-Wörsten, C.; Posthaus, H.; Bacciarini, L.; Breitenmoser, U. Causes of mortality in reintroduced Eurasian lynx in Switzerland. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002, 38, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmer, D.; Guenther, D.; Layne, J. Ecology of the Bobcat in South-Central Florida. Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1988, 33, 159–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

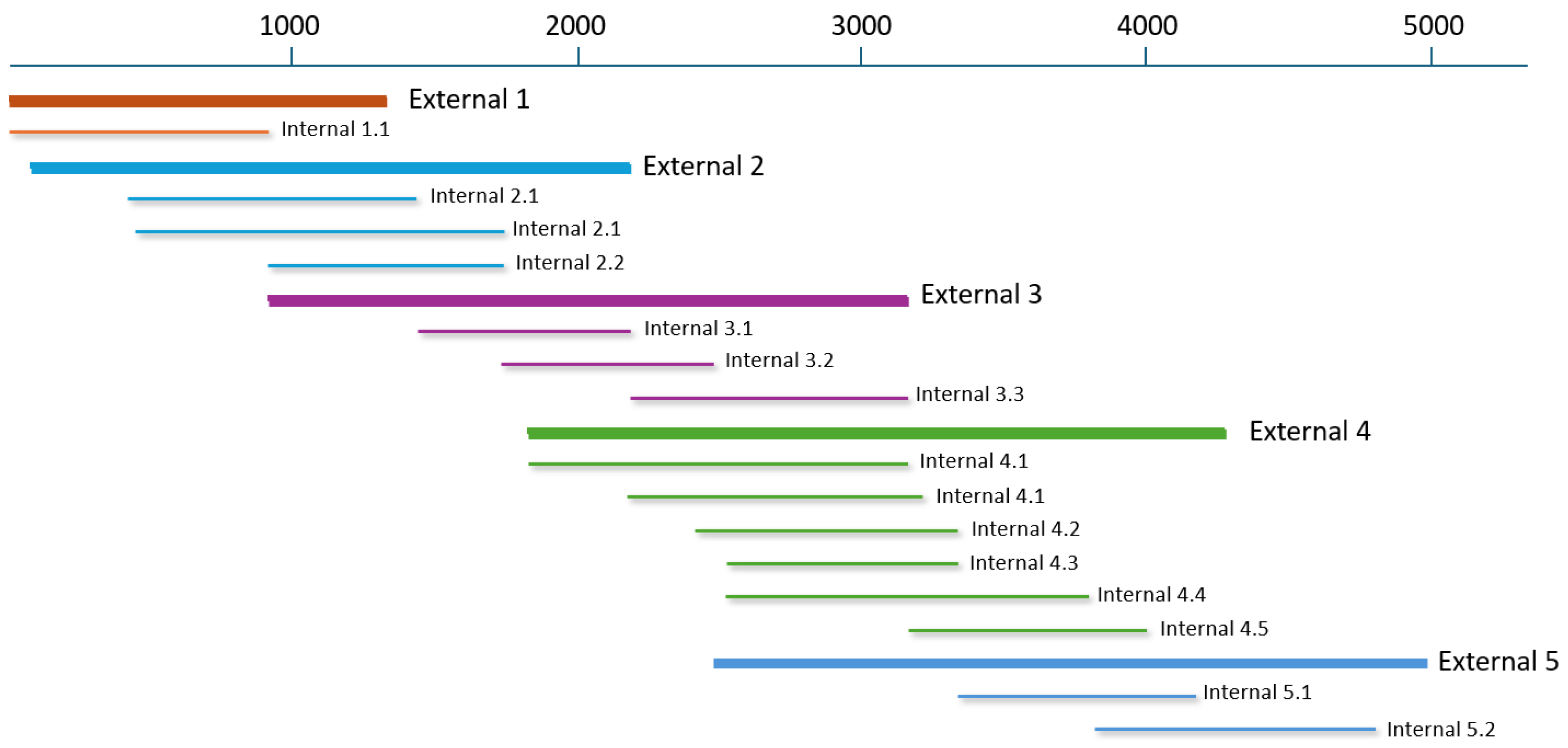

| GenBank Acc. No. | Host | Sample | Total nt sequenced | ORF1 NS1 and NS2 | ORF2 VP1 and VP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP781551 | Lynx pardinus | LG100 | 4589 | nt 64-2070 | nt 2077-4333 |

| PQ436979 | Felis catus | LG15 | 4543 | nt 52-2058 | nt 2065-4320 |

| PQ436980 | Canis lupus domesticus | LG151 | 4478 | nt 23-2029 | nt 2036-4291 |

| AMINO ACID POSITION (VP2) |

5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 21 | 29 | 37 | 52 | 58 | 66 | 67 | 70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG100LYNX | A | V | Q | D | P | R | R | T | G | G | K | W | S | R | H |

| LG15CAT | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| LG151dog | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MH559110 | P | F | H | N | . | K | K | . | . | . | N | G | T | K | L |

| OQ266795 | P | F | H | N | . | K | K | . | . | . | N | G | T | K | L |

| MW811187 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| KP280068 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OR227624 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| KX685354 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | D | . | . | . | . | . |

| OR198066 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MG764510 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ044015 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| KR002793 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OM721656 | G | . | . | . | S | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OP972595 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OR230516 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OP611195 | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MK388674 | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | S | . | . | . | . | . | . |

|

AMINO ACID POSITION (VP2) |

80 | 85 | 87 | 91 | 93 | 103 | 224 | 232 | 234 | 267 | 297 | 300 | 305 | 322 | 323 |

| LG100lynx | K | N | M | A | K | V | G | V | H | F | S | A | D | T | D |

| LG15CAT | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| LG151dog | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | Y | A | G | Y | . | N |

| MH559110 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OQ266795 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MW811187 | . | . | . | S | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| KP280068 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OR227624 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| KX685354 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| OR198066 | . | . | . | . | . | . | E | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MG764510 | . | I | . | . | . | . | . | I | . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| MZ044015 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | Y | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| KR002793 | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | Y | A | G | Y | . | N |

| OM721656 | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | Y | A | G | Y | . | N |

| OP972595 | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | Y | A | G | Y | A | N |

| OR230516 | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | . | A | G | Y | . | N |

| OP611195 | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | Y | A | G | Y | . | N |

| MK388674 | R | . | L | . | N | A | . | I | . | Y | A | G | Y | . | N |

|

AMINO ACID POSITION (VP2) |

324 | 370 | 373 | 390 | 412 | 426 | 440 | 447 | 564 | 568 | |||||

| LG100lynx | Y | Q | D | T | G | N | T | I | N | A | |||||

| LG15cat | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| LG151dog | I | R | . | . | . | E | . | . | S | G | |||||

| MH559110 | . | . | N | A | R | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| OQ266795 | . | . | N | A | R | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| MW811187 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| KP280068 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| OR227624 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| KX685354 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| OR198066 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| MG764510 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| MZ044015 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | |||||

| KR002793 | I | . | . | . | . | D | A | . | S | G | |||||

| OM721656 | I | . | . | . | . | D | A | . | S | G | |||||

| OP972595 | I | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | S | G | |||||

| OR230516 | L | . | . | . | . | D | . | . | S | G | |||||

| OP611195 | I | R | . | . | . | E | . | M | S | G | |||||

| MK388674 | I | R | . | . | . | E | . | . | S | G |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).