Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Research Problem Statement

1.3. Research Questions

1.4. Research Contributions

1.5. Paper Organization

2. Need for an Educational Technology Adoption Model in Developing Countries

2.1. Current Research Status on Educational Technologies Adoption Models for Developing Countries

2.2. Difference Between Advanced and Developing Countries in the Adoption of Educational Technology

- Investment in Infrastructure and Resources [6]: Advanced countries invest heavily in educational technology, providing modern tools like computers, projectors, internet connection, and others while developing countries often rely on traditional methods due to a lack of infrastructure;

- Teacher Training and Support [6]: Advanced nations have established programs for integrating technology into education, ensuring teachers are trained in using these tools effectively. In contrast, developing countries face foundational challenges that hinder teacher training and technology adoption;

2.3. Challenges Facing Developing Countries in the Adoption of Education Technologies

- Limited access to resources [6] : The lack of technical support, electricity, internet, devices, and financial resources significantly hampers technology adoption, especially in rural areas and emerging economies;

- Lack of training and skills [6]: Teachers in developing countries often receive inadequate training and support, resulting in low technology adoption rates. Many lack the professional readiness to effectively utilize emerging technologies in education;

- Cultural and social factors [12]: These factors heavily influence technology adoption, particularly in mobile learning within Arab Gulf countries, affecting acceptance among students and instructors.

- Resistance to technology [13]: Teachers' attitudes toward technology create challenges in the classroom. Their willingness to integrate technology depends on perceived benefits versus concerns, complicating adoption efforts;

- Overemphasis on technology and underemphasis on pedagogy: Many programs prioritize acquiring technology over its integration into educational frameworks and pedagogy.

3. Construction of ETADC Model

3.1. Selection of Base Models for Constructing ETADC

3.1.1. The Scope of Searching Base Models

3.1.2. The Properties of Base Models

- The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) developed by Davis [14] highlights Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) in adopting new technology, originating from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA). However, it does not account for subjective norms or guides on enhancing technology's usability;

- TAM2 and TAM3 developed by Venkatesh and Davis [15] expand on TAM's core constructs by including components like Subjective Norms (SN), Image (IM), Job Relevance (JR), and additional factors in TAM3 such as Results Demonstrability (RD) and Computer Self-efficacy (CSE). Both models are complex and focus on technology adoption within organizational settings;

- UTAUT2 developed by Venkatesh [18] adapts this framework for consumer contexts but similarly suffers from increased complexity due to multiple moderators. Overall, these models reflect a shift from individual perceptions to broader factors influencing technology adoption.

3.2. Identifying Components for the ETADC Model from the Base Models

3.2.1. The Sharing Cause-Effect Links of Dominant Technologies’ Adoption Models and Hypotheses Development

- PE→ BIU

| Model | Core components | Cause-Effect Links | ||

|

TAM [14] |

PU, PEU, AT, BIU, UB | 1) PU → BIU 2) PEU → AT |

3) PEU → PU 4) PU → AT |

5)AT → BIU 6)BI →UB |

|

TAM2 [15] |

PU, PEU, BIU, UB, SN, IM, JR, RD, OPQ | 1) PEU → PU 2) PU → BIU 3) PEU→BIU 4)BI→UB |

5)SN→ PU 6)SN→ BIU 7)SN→IM 8)IM→ PU |

9)JR→ PU 10)RD→ PU 11)OPQ→ PU |

|

TAM3: [19] |

PU, PEU, BIU, UB, SN, IM, JR, RD, OPQ, CSE, PEC, CA, PENJ, OU, CPF, moderators (Voluntariness, Experience) | 1)PEU → PU 2)PU → BIU 3)PEU→BIU 4)BI → UB 5)SN→ PU 6)SN→ IU |

7)SN→IM 8)IM→ PU 9)JR→ PU 10)RD→ PU 11)OPQ→ PU 12)CSE→PEU |

13)PEC→ PEU 14)CANX→PEU 15)CPF→ PEU 16)PENJ→PEU 17)OU→ PEU |

|

UTAUT: [16] |

PE, EE, SI, FC, BIU, Moderator variables (gender, age, experience, and voluntariness) | 1)PE→ BIU 2)EE → BIU |

3)SI → BIU 4) FC→ BIU |

5)FC→ UB 6)B →UB |

|

UTAUT2: [18] |

PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, H, PV, BIU, Moderator variables (gender, age, experience, and voluntariness) | 1)PE→ BIU 2)EE → BIU 3)SI → BIU 4)FC→ BIU |

5)FC → UB 6)HM→ BIU 7)PV→ BIU |

8)H→BIU 9)H→ UB 10)BIU→UB |

- EE → BIU

- SI → BIU

3.2. The Sharing Components of Many Educational Technology Adoption Models

| Studies | Base models | components | Cause-Effect Links | |||

| [20] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, PV, BIU, PI | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU 3)SI→BIU |

4)FC→BIU 5)HM→BIU |

6)PV→BIU 7)PI→BIU |

8) PI→PE 9)PI→EE |

| [21] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, H, BIU, CS, TR | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU |

3)SI→BIU 4)FC→BIU |

5)HM→BIU 6)H→BIU |

7)CS→BIU 8)TR→BIU |

| [22] | TAM |

PEU, PU, SE, PEN, PCR, PI, PV, BIU |

1)PI →SE 2)PI→PU 3)PI →PEU 4)PI→BIU |

5)SE→PU 6)SE→PEU 7)PCR→PU |

8)PCR→BIU 9)PEU→PU 10)PEU→PENJ |

11)PEU→BIU 12)PU→BIU 13)PENJ→BIU |

| [23] | TAM and UTAUT | PU, PEU, AT, FC, PENJ, PRA, MSE, IU | 1)PENJ→PU 2)PENJ→AT 3)PU→IU |

4)PU→AT 5)AT→IU 6)FC →IU |

7)FC→PEU 8)PEU→PU 9)PEU→AT |

10)MSE→PEU 11)PRA→PU |

| [24] | UTAUT | PE, EE, FC, BIU, PR, AT, AAHE | 1)PR→AT 2)PE→AT |

3)EE →AT 4)FC→EE |

5)FC→BIU 6)AT→BIU |

7)BIU→AAHE |

| [25] | TAM | PE, EE, BIU |

1)AT→BIU 2)PEU→AT |

3)PEU→PU 4)BIU →AT |

5)ST→PU 6)ST→PEU |

7)ST→A |

| [26] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, PV, BIU, UB | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU |

3)SI→BIU 4) FC→BIU |

5)FC→UB 6)HM→BIU |

7)PV→BIU 8)BIU→UB |

| [27] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, H, PV, BIU, UB, PI | 1) PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU 3)SI →BIU |

4)FC→BIU 5)FC→UB 6)HM→BIU |

7)PV→BIU 8)H→BIU 9)H→UB |

10)BIU→UB 11)PI→BIU |

| [28] | IOD | WTU, PT, RA or PE, CP, CM, EX or EE | 1) CP→WTU 2)CM→WTU 3) EE→WTU |

4) RA→WTU 5) PT→WTU |

||

| [29] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, H, BIU, PI | 1)PE→ BIU 2)EE → BIU 3)SI →BIU |

4) FC→BIU 5)FC →UB 6)HM→BIU |

7)H→BIU 8)H→UB |

9)BIU→UB 10)PI→ BIU |

| [30] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, PV, BIU, |

1) PE→BIU 2)EE →BIU |

3)SI → BIU 4) FC→BIU |

5)HM→BIU 6)PV→BIU |

|

| [31] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, PV, WU |

1) PE→ WTU 2)EE → WTU |

3)SI → WTU 4) FC→ WTU |

5)HM→ WTU 6)PV→ WTU |

|

| [32] | TAM, TAM2 and TAM3 | PU, PEU, AT, SN or SI, IU, SE, JR, OPQ, PEC |

1) PU→IU 2) PU→AT 3) PEU→AT 4) PEU→PU |

5)AT→IU 6)SN→ PU 7)OPQ→PU |

8)PEC→ PEU 9)PENJ →PEU 10)SE→ PEU |

|

| [33] | UTAUT | PE, EE, SI, BIU, UB | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU |

3)SI → BIU 4)BI → UB |

||

| [34] | UTAUT | PE, EE, SI, FC, BIU, U | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU 3)SI→BIU |

4)FC→ UB 5)BIU → UB |

||

| [35] | TAM | PEU, PU, BIU, PEN | 1)PEN→PEU 2)PEU→BIU |

3)PEU → PU 4)PU →BIU |

||

| [36] | TAM | PEU, PU, SI, PT, PA, AN, BIA | 1)PEU→BIA 2)PU→BIA |

3)SI→BIA 4)PT → BIA |

5)PA → BIA 6)AN →BIA |

|

| [37] | TAM | PEU, PU, U, AT, BIU, EF, PL, SA | 1)AT→BIU 2)PU→AT 3)PU→BIU 4)PEU→AT |

5)PEU→PU 6)SA→PU 7)SA→AT 8)SA→BIU |

9)SA →U 10)PEU→SA 11)EF→PU 12)EF→PEU |

13)EF→SA 14)PL→PU 15)PL→PEU 16)PL→SA |

| [38] | TAM | PU, PEU, IU, INTR, IMRN, IMGN | 1)PU→IU 2)PEU→IU |

3)INTR→PU 4)INTR→PEU |

5)IMGN→PU 6)IMGN→PEU |

7)IMRN→ PU 8)IMRN→PEU |

| [39] | UTAUT | PE, EE, SI, FC, BIU, IV | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU |

3)SI→BIU 4) FC→BIU |

5)FC → UB 6)BIU → UB |

7) IV→ BIU 8)IV → UB |

| [40] | UTAUT2 | PE, EE, SI, FC, H, HM, PV, BIU, GD, AG, EX | 1)PE→BIU 2)EE→BIU 3)SI →BIU |

4) FC→BIU 5)HM→BIU 6)PV→ BIU |

7)H→ BIU 8)GD→ BIU |

9) AG→ BIU 10)EX → BIU |

| [41] | TAM | PEU, IU, AW or SI, OA or FC, TC | 1)SI→ FC 2)TC →FC 3)SI→ PEU |

4)FC→PEU 5) PEU→IU |

||

3.2.1. Performance Expectancy

3.2.2. Effort Expectancy

3.2.3. Social Influence

3.2.4. Facilitating Conditions

3.2.5. Special Links of ETADC for Considering the Context of Developing Countries' Education Settings

3.2.6. ETADC Structure

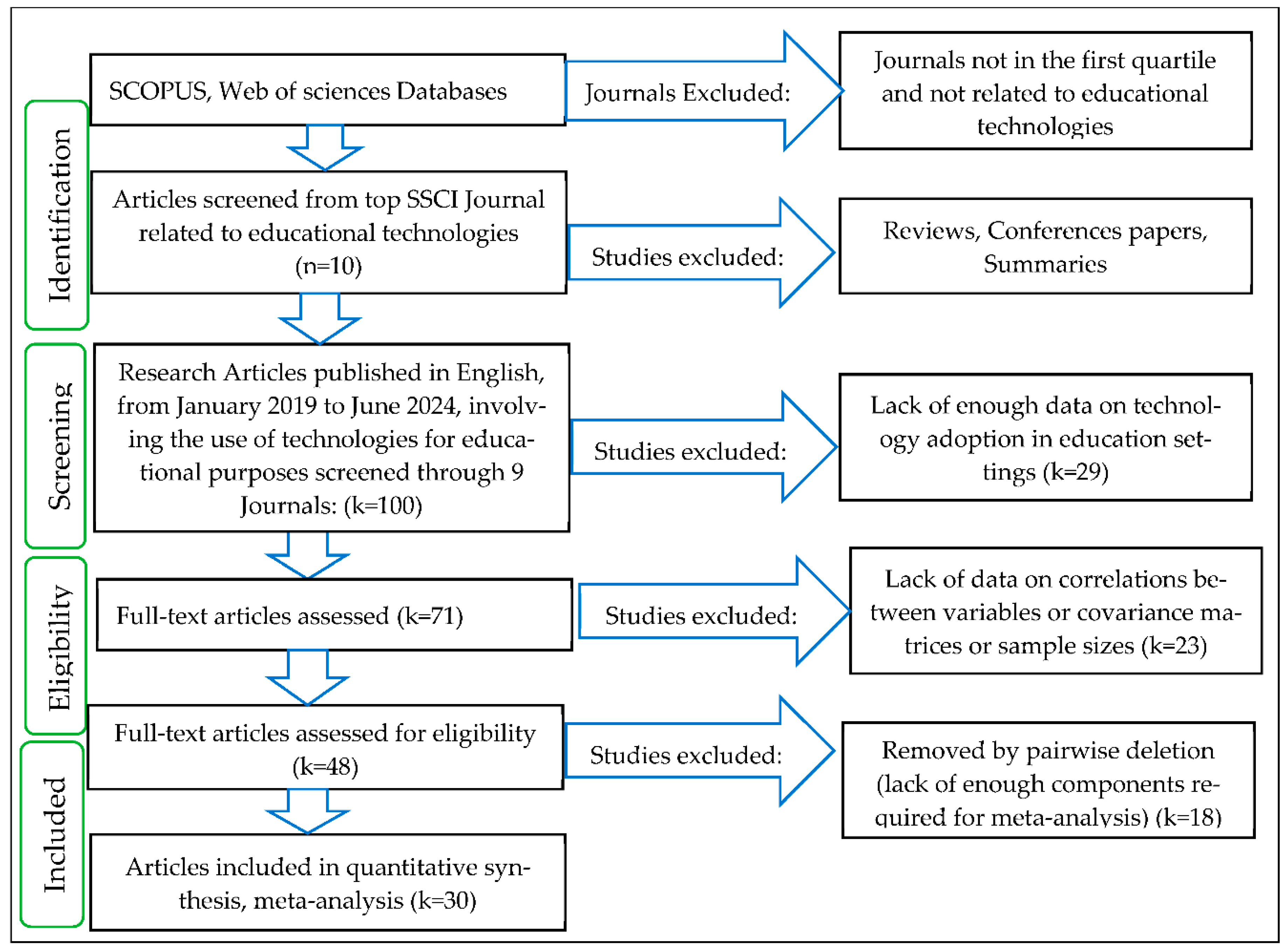

4. Validation of the Developed Educational Technology Adoption in Developing Countries (ETADC) Model Through Meta-Analytic and Structural Equation Modeling (MASEM)

4.1. Meta-Analytic Dataset Preparation

| References | N | PE→EE | PE→SI | PE→AU | PE→FC | PE→PV | EE→SI | EE→AU | EE→FC | EE→PV | FC→SI | FC→AU | FC→PV | SI→PV | SI→AU | PV→AU |

| [26] | 161 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.7 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.59 |

| [40] | 152 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.62 | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.62 |

| [27] | 629 | 0.351 | 0.565 | 0.809 | 0.341 | 0.415 | 0.213 | 0.39 | 0.71 | 0.339 | 0.302 | 0.431 | 0.462 | 0.335 | 0.601 | 0.479 |

| [57] | 605 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.35 | NA | NA | 0.39 | 0.3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.39 | NA |

| [58] | 418 | 0.561 | NA | 0.412 | NA | NA | NA | 0.353 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [41] | 54 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.529 | 0.658 | 0.658 | NA | 0.366 | 0.573 | NA | NA | 0.526 | NA |

| [28] | 178 | 0.341 | NA | 0.404 | 0.213 | NA | NA | 0.396 | 0.413 | NA | NA | 0.334 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [21] | 365 | 0.804 | 0.648 | 0.637 | 0.654 | NA | 0.638 | 0.57 | 0.653 | NA | 0.539 | 0.436 | NA | NA | 0.66 | NA |

| [59] | 534 | 0.596 | 0.583 | 0.841 | 0.595 | NA | 0.42 | 0.636 | 0.798 | NA | 0.489 | 0.629 | NA | NA | 0.612 | NA |

| [30] | 141 | 0.508 | 0.478 | 0.41 | 0.552 | 0.64 | 0.477 | 0.324 | 0.574 | 0.327 | 0.638 | 0.507 | 0.548 | 0.6 | 0.416 | 0.508 |

| [31] | 352 | 0.734 | 0.65 | 0.618 | 0.653 | 0.491 | 0.699 | 0.588 | 0.693 | 0.491 | 0.781 | 0.672 | 0.669 | 0.676 | 0.742 | 0.586 |

| [20] | 537 | 0.632 | 0.528 | 0.637 | 0.635 | 0.606 | 0.507 | 0.637 | 0.609 | 0.577 | 0.501 | 0.605 | 0.564 | 0.484 | 0.474 | 0.585 |

| [32] | 218 | 0.711 | 0.552 | 0.676 | NA | NA | 0.428 | 0.565 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.498 | NA |

| [33] | 186 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.68 | NA | NA | 0.58 | 0.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.69 | NA |

| [25] | 156 | 0.468 | NA | 0.123 | NA | NA | NA | 0.132 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [39] | 99 | 0.687 | 0.742 | 0.666 | 0.771 | NA | 0.642 | 0.463 | 0.735 | NA | 0.712 | 0.68 | NA | NA | 0.651 | NA |

| [24] | 329 | 0.544 | NA | 0.511 | 0.561 | NA | NA | 0.499 | 0.556 | NA | NA | 0.506 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [60] | 462 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.7 | NA | NA | 0.55 | 0.64 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.64 | NA |

| [23] | 306 | 0.517 | NA | 0.673 | 0.528 | NA | NA | 0.535 | 0.676 | NA | NA | 0.601 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [34] | 194 | 0.748 | 0.584 | 0.701 | 0.584 | NA | 0.493 | 0.642 | 0.715 | NA | 0.425 | 0.519 | NA | NA | 0.645 | NA |

| [61] | 546 | 0.595 | 0.577 | NA | 0.559 | NA | 0.701 | NA | 0.525 | NA | 0.63 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [62] | 233 | 0.452 | 0.478 | 0.671 | NA | NA | 0.381 | 0.454 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.583 | NA |

| [63] | 450 | 0.613 | 0.626 | 0.796 | NA | NA | 0.338 | 0.573 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.629 | NA |

| [22] | 574 | 0.529 | NA | 0.741 | NA | NA | NA | 0.51 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [35] | 58 | 0.7 | NA | 0.758 | NA | NA | NA | 0.641 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [36] | 207 | 0.613 | 0.433 | 0.56 | NA | NA | 0.333 | 0.502 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.672 | NA |

| [64] | 89 | 0.649 | 0.48 | 0.752 | NA | NA | 0.524 | 0.699 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.562 | NA |

| [37] | 223 | 0.507 | NA | 0.579 | NA | NA | NA | 0.589 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [38] | 134 | 0.396 | NA | 0.765 | NA | NA | NA | 0.366 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [65] | 344 | 0.829 | NA | 0.745 | NA | NA | NA | 0.81 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

4.2. Data Analysis Using Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling

| PE | FC | SI | EE | PV | AU | |

| PE | 1 | 8880 (29) |

6160 (19) |

8334 (28) |

4523 (14) |

1972 (6) |

| FC | 0.588*** | 1 | 6214 (20) |

8388 (29) |

4577 (15) |

1972 (6) |

| SI | 0.545 *** |

0.466*** |

1 | 3764 (12) |

4031 (14) |

1972 (6) |

| EE | 0.623 *** | 0.517 *** | 0.507 *** |

1 | 1972 (6) |

5668 (19) |

| PV | 0.536 *** | 0.629 *** | 0.536 *** | 0.465 *** |

1 | 1972 (6) |

| AU | 0.542** | 0.458 *** | 0.547*** | 0.581 *** | 0.551*** | 1 |

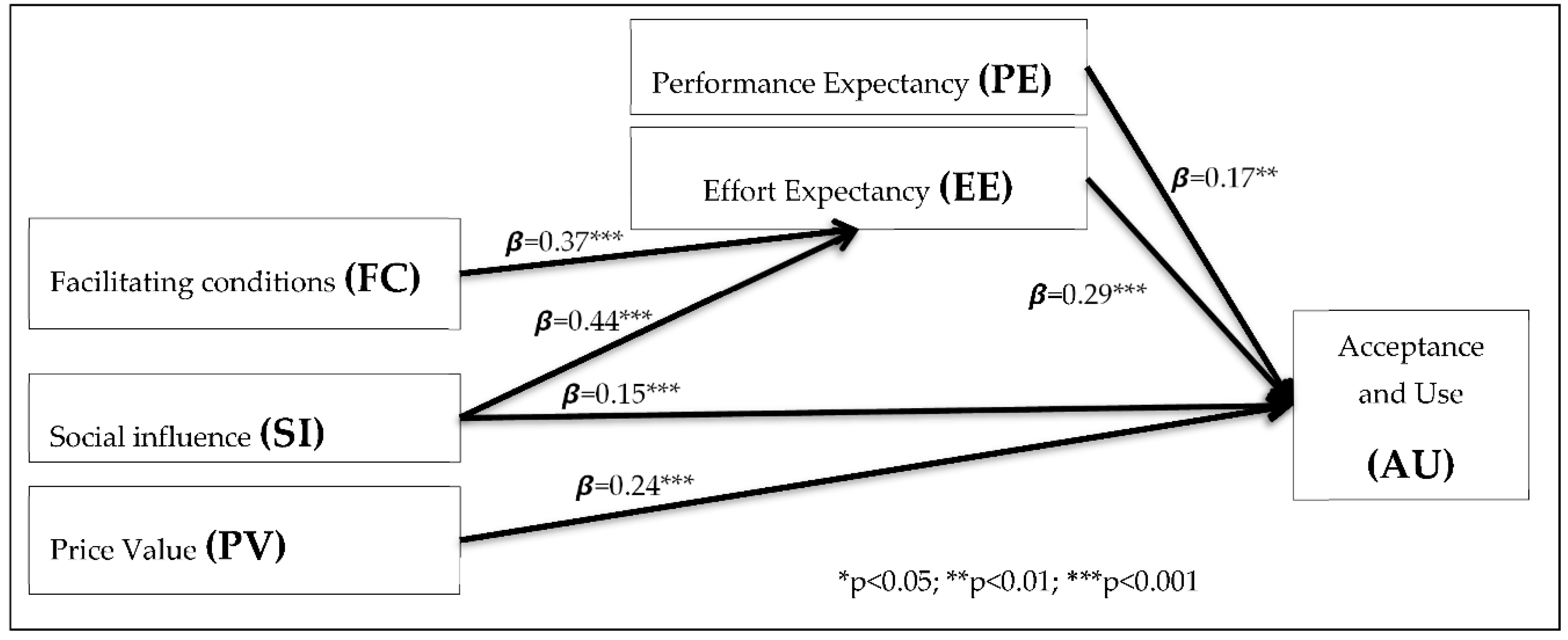

4.3. Results Interpretation and ETADEC Model Validation

- First, check Model Fit: Evaluate overall model fit using indices like RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis’s index);

- Second, assess the explanatory power of the model(R²);

- Third, assess Path Coefficients(β): Ensure the significance and strength of path coefficients align with theoretical expectations.

4.3.1. ETADEC Model Fit Assessment

| Indices | Recommended values [68] | ETADC Testing values | Conclusion |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) |

≤ 0.05; reasonable fit > 0.1; poor fit. |

0.0387 | Good model fit |

| Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) |

≤ 0.08 = acceptable fit | 0.0476 | Good model fit |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) |

= 1; perfect fit | 0.9916 | Good model fit |

| ≥ 0.95; excellent fit | |||

| Tucker-Lewis’s index (TLI) | ≥0.9; good fit; | 0.9578 | Good model fit |

4.3.2. Assessment of the ETADC Model’s Explanatory Power (R²)

| Independent variables | Dependent variable | Coefficient of determination (R2) | Conclusion | |

| Social Influence (SI), Facilitating Conditions (FC) |

Effort Expectancy (EE) | 53% or 0.53 | Acceptable | |

| Performance Expectancy (PE), Social influence (SI), Price Value (PV), Effort Expectancy (EE) |

Acceptance and Use (AU) | 52% or 0.52 | Acceptable | |

4.3.3. Assessment of the ETADC Model’s Path Coefficients(β)

| Hypotheses |

Paths (Connections between variables) |

Path Coefficients (β) |

Std. Error |

z value | p-values | Statistical Significance | Conclusion |

| H2 | Effort Expectancy → Acceptance and Use | 0.29 | 0.040 | 7.28 | <0.001 | Significant | supported |

| H1 | Performance Expectancy→ Acceptance and Use |

0.17 | 0.061 | 2.77 | <0.01 | Significant | supported |

| H6 | Price Value → Acceptance and Use | 0.24 | 0.032 | 7.41 | <0.001 | Significant | supported |

| H5 | Social Influence → Acceptance and Use | 0.15 | 0.044 | 3.38 |

<0.001 | Significant | supported |

| H3 | Facilitating Conditions → Effort Expectancy | 0.37 | 0.035 | 10.62 |

<0.001 | Significant | supported |

| H4 | Social Influence → Effort Expectancy | 0.44 | 0.042 | 10.33 | <0.001 | Significant | supported |

4.3.4. Practical Application of the ETADC Model

- Performance expectancy (PE): A technological factor similar to perceived usefulness, helps identify suitable education technology by analyzing features;

- Price value (PV): A technological factor essential when considering technology purchases;

- Facilitating conditions (FC): A factor that pivots on the availability of devices, resources, and infrastructure including top management support, and expertise, is crucial for successful technology adoption through Effort expectancy (EE);

- Effort expectancy (EE): A factor that pivots on users' capability impacted by FC and SI;

- Social Influence (SI): A significant socio-cultural factor impacting both technology identification and adoption processes.

| Type of Educational technology | PE |

PV Pricing |

FC |

EE Users (Downloads) |

SI | |||||

| PE1 Features |

PE2 Category |

FC1 Required devices |

FC2 Download Size |

SI1 Technology maturity |

SI2 Teacher Approved |

SI3 reviews |

SI4 Ratings on market |

|||

| 1. Real-time engagement technologies (Quizlet) | Promote engagement, personalized learning, creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving skills |

Education | $1.99 - $35.99 | computers, iPads, iPhones, iTouches, Android tablets, and smartphones | 39 MB | 10M+ | Yes | Yes | 712K | 4.7

|

| 2. Design and creativity technologies (Canva) | Education | $1.49 - $300 | 27 MB | 100M+ | Yes | Yes | 19.3M | 4.8

|

||

| 3. Interactive learning labs (PhET Simulations) | Education | 0.99$ | 123MB | 50K+ | Yes | Yes | 531 | 4.7

|

||

| 4. Language learning technology (Duolingo) | Education | $0.99 - $239.9 | 81MB | 500M+ | Yes | Yes | 30.5M | 4.7

|

||

| 5. Virtual Reality and Augmented reality (CamToPlan) | Business and Education | Free – $17.99 | 20M | 100K+ | Yes | Yes | 7.38K | 4.5

|

||

| 6. Robotics (Mio, the Robot) | Education | FREE | 48 MB | 100K+ | Yes | Yes | 1.25K | 3.1

|

||

| 7. Game-based learning platforms (Kahoot) | Education | FREE | 93 MB | 50M+ | Yes | Yes | 751K | 4.7

|

||

| 8. Learning Management Systems (Google Classroom) | Education | FREE | 21.65 MB | 100M+ | Yes | Yes | 2.04M | 4.1

|

||

| 9. Interactive learning platforms (Nearpod) | Education | FREE | 3 MB | 1M+ | Yes | Yes | 7.04K | 2.2

|

||

| 10. Open Education Resources (Khan Academy) | Education | FREE | 28MB | 10M+ | Yes | Yes | 167K |

4.2

|

||

| 11. Three-dimensional printing (Tinkercad) | Education | FREE | 100K+ | Yes | Yes | 825 |

2.5

|

|||

- 5 stars if the technology is designed for Education purposes;

- 4 stars if the technology is developed as a tool that can be applied for Education purposes;

- 3 stars if the technology is designed for Business purposes and can be applied in Education;

- 2 stars if the technology is designed for Entertainment but can be applied for Education purposes;

- 1 star if the technology is designed for Lifestyle or others but can be applied for Education purposes.

- Enhance engagement,

- Promote personalized learning,

- Promote creativity,

- Promote critical thinking,

- Promote problem-solving skills.

- 5 stars if the educational technology can offer at least five or more features;

- 4 stars if the educational technology can offer at least four features;

- 3 stars if the educational technology can offer at least three features;

- 2 stars if the educational technology can offer at least two features;

- 1 star if the educational technology can offer at least one feature.

- 5 stars if the educational technology is accessible for FREE or 0$ (pricing per item);

- 4 stars if the educational technology is accessible between 1 $ -20 $ (pricing per item);

- 3 stars if the educational technology is accessible between 20 $ -50$ (pricing per item);

- 2 stars if the educational technology is accessible between 50$ -100 $ (pricing per item);

- 1 star if the educational technology is accessible from 100 $ and above (pricing per item).

- 5 stars if the educational technology is available for five or more types of devices;

- 4 stars if the educational technology is available for four types of devices;

- 3 stars if the educational technology is available for three types of devices;

- 2 stars if the educational technology is available for two types of devices;

- 1 star if the educational technology is available for one type of device.

- 5 stars if the Download Size of educational technology is below 50 MB;

- 4 stars if the Download Size of educational technology is above 50 MB to 100 MB;

- 3 stars if the Download Size of educational technology is above 100 MB to 150 MB;

- 2 stars if the Download Size of educational technology is above 150 MB to 199 MB;

- 1 star if the Download Size of educational technology is 200 MB or above.

- 5 stars if the educational technology has above 100M downloads;

- 4 stars if the educational technology has 10M+ to 100M downloads;

- 3 stars if the educational technology has 100K+ to 10M downloads;

- 2 stars if the educational technology has 50K to 100K downloads;

- 1 star if the educational technology has below 50K downloads.

- 5 stars if the educational technology has reached the Plateau of productivity (the technology becomes widely accepted and integrated into regular use);

- 4 stars if the educational technology has reached the slope of enlightenment (gradual understanding and practical applications of the technology begin to crystallize as more success stories emerge);

- 3 stars if the educational technology has reached the trough of disillusionment (realization of the technology’s limitations leading to disappointment and reduced interest);

- 2 stars if the educational technology has reached the peak of inflated expectations (high expectations are fueled by hype and speculative success stories);

- 1 star if the educational technology is still on the Technology trigger (the initial emergence of the technology, generating interest and media buzz).

- 5 stars if Teachers have approved the educational technology;

- 0 star if Teachers have not yet approved the educational technology.

- 5 stars if the educational technology has above 1M reviews;

- 4 stars if the educational technology has 100K+ to 1M reviews;

- 3 stars if the educational technology has 50k+ to 100k reviews;

- 2 stars if the educational technology has 10k to 50k reviews;

- 1 star if the educational technology has below 10k reviews.

- 5 stars if the educational technology is rated 4.5 stars and above;

- 4 stars if the educational technology is rated 3.5 to 4.4 stars;

- 3 stars if the educational technology is rated 2.5 to 3.4 stars;

- 2 stars if the educational technology is rated 1.5 to 2.4 stars;

- 1 star if the educational technology is rated 1.4 stars and below.

| Type of Educational technology | PE=(PE1+PE2)/2 | PV | FC=(FC1+FC2)/2 | EE | SI=(SI1+SI2+SI3+SI4) /4 | Adoption rate =(PE+PV+FC+EE+SI) /5 | |||||||||

| PE1 | PE2 | PE | FC1 | FC2 | FC | SI1 | SI2 | SI3 | SI4 | SI | |||||

| 1. Real-time engagement technologies (Quizlet) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4.7 |

4.5

|

|

| 2. Design and creativity technologies (Canva) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

4.8

|

|

| 3. Interactive learning labs (PhET Simulations) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

3.8

|

|

| 4. Language learning technology (Duolingo) | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

4.6

|

|

| 5. Virtual Reality and Augmented reality (CamToPlan) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4.5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

4.3

|

|

| 6. Robotics (Mio, the Robot) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3.7 |

4.3

|

|

| 7. Game-based learning platforms (Kahoot) | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4.7 |

4.5

|

|

| 8. Learning Management Systems (Google Classroom) | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.7 |

4.8

|

|

| 9. Interactive learning platforms (Nearpod) | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3.2 |

4.1

|

|

| 10. Open Education Resources (Khan Academy) | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4.5 |

4.6

|

|

| 11. Three-dimensional printing (Tinkercad) | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4.5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 3.5 |

4.1

|

|

5. Research Implications and Conclusion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions: Model’s Superiority

- It was specifically developed for the unique challenges of developing countries, whereas most primary models focus on advanced countries, making them less effective in this context.

- The ETADC model is tailored for education and validated with data exclusively from the education sector, unlike previous models that were adapted from other fields.

- Unlike primary models that target specific technologies, the ETADC addresses educational technology adoption in general.

- It uses a large sample size (8934) from various countries, enhancing its validity, while primary models often rely on small, localized samples.

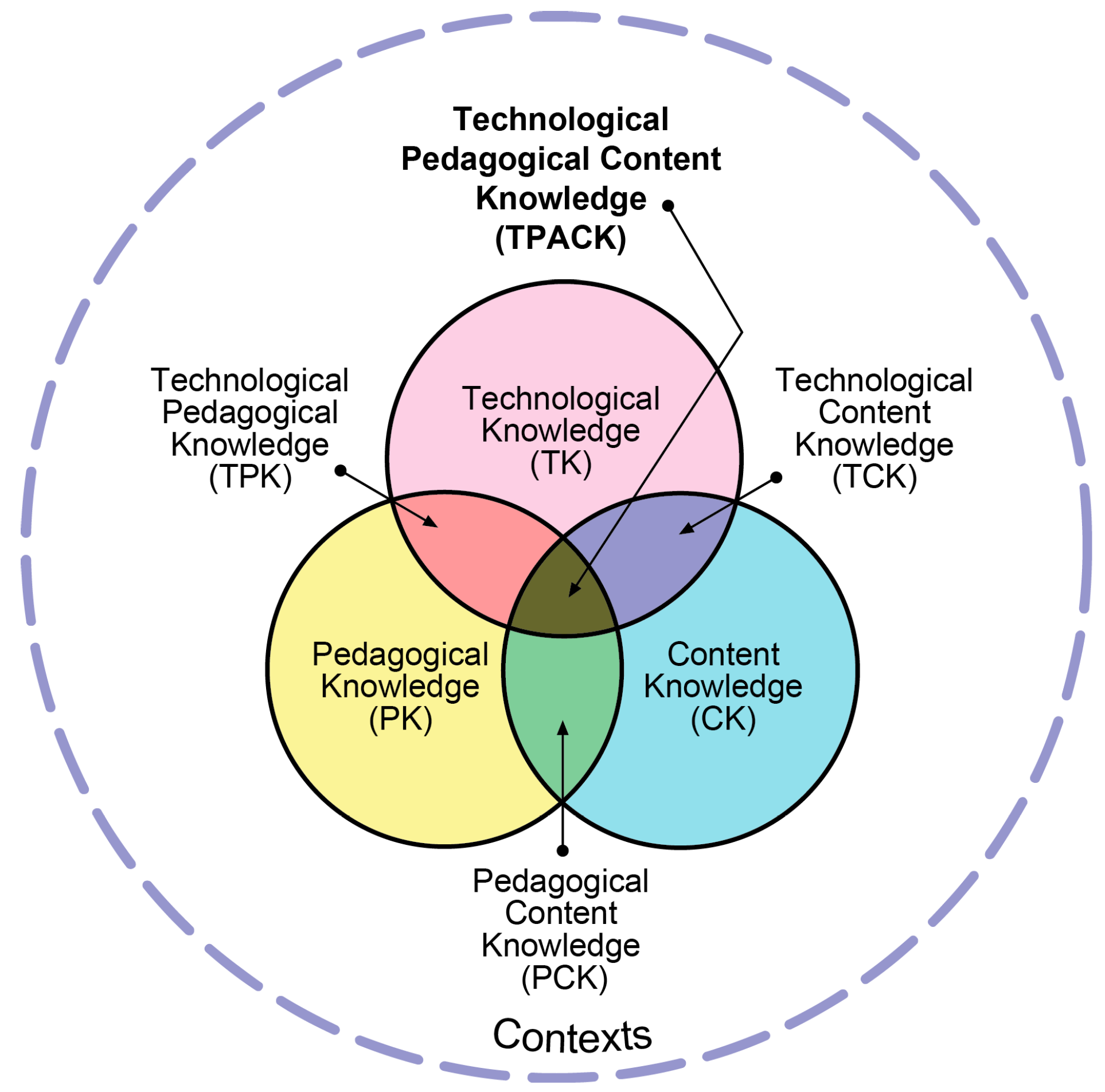

- The ETADC model considers a crucial pedagogical variable: TPACK articulates the essential knowledge that educators must possess to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices.

- The ETADC model considers crucial variables such as cost-effectiveness, customization, alignment with academic goals, and the unique cultural, infrastructural, and economic factors in developing countries.

5.2. Practical Implications

- Performance Expectancy: Institutions should meticulously assess a technology's features and its relevance to curriculum goals to ensure it enhances teaching-learning outcomes before adoption.

- Facilitating Conditions and Effort Expectancy: Successful technology adoption requires strong organizational support, adequate resources, training, and teachers who can effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices.

- Price Value: The benefits of adopting a new technology must outweigh its costs; otherwise, it is not worth the investment.

- Effort Expectancy: Through TPACK, aims to articulate the essential knowledge that educators must possess to effectively integrate technology into their teaching practices.

- Social Influence: Developing countries can enhance their educational standards by learning from successful technology integration in advanced countries, such as China’s community-based professional development strategies.

5.3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| % | Percent | JR | Job Relevance |

| A | Anxiety | MASEM | Meta-analytic Structural Equation Modeling |

| AG | Age | MSE | Mobile Self-Efficacy |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence | N | Number of the studies |

| AN | Anthropomorphism | OA | Operational ability |

| AT | Attitude Toward Using | OPQ | Output Quality |

| AT | Attitude | OU | Objective Usability |

| AU | Acceptance and Use | PA | Perceived Autonomy |

| AW | Awareness | PCR | Perceived cyber risk |

| BIA | Behavior Intention to Adopt | PE | Performance Expectancy |

| BIU | Behavior Intention | PEC | Perception of external control |

| BIU | Behavior Intention to Use | PENJ | Perceived Enjoyment |

| CA | Computer Anxiety | PEU | Perceived Ease of Use |

| CBAM | Concerns-Based Adoption Model | PI | Personal Innovativeness |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index | PL | Playfulness |

| CM | Complexity | PR | Perceived risk |

| CP | Compatibility | PRA | Perceived relative advantage |

| CPF | Computer Playfulness | PT | Perceived Trust |

| CS | Cyber Security | PU | Perceived usefulness |

| CSE | Computer self-efficacy | PV | Price Value |

| DCs | Developing Countries | R2 | The coefficient of determination |

| DF | Degree of freedom | RA | Relative advantage |

| DOI | Diffusion of Innovations Theory | RD | Results Demonstrability |

| EdTech | Educational Technology | RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| EE | Effort Expectancy | SA | Satisfaction |

| EF | Efficiency | SE | Self-Efficacy |

| ETADC | Educational Technology Adoption in Developing Countries | SEM | Structural Equation Modelling |

| EX | Experience | SI | Social influence |

| FC | Facilitating Conditions | SIS | social isolation |

| GD | Gender | SN | Subjective Norms |

| GOFI | Goodness-of-fit indices | SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual |

| H | Hypothesis | ST | Stress |

| H | Habit | TAM | Technology Acceptance Model, |

| HEIs | Higher education institutions | TC | Technology challenges |

| HM | Hedonic Motivation | TLI | Tucker-Lewis’s index |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies | TOE | Technology-Organization-Environment |

| IM | Image | TPACK | Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge |

| IMGN | Imagination | TR | Trust |

| IMRN | Immersion | TSSEM | Two-Stage Structural Equation Modeling |

| INTR | Interaction | TTF | Task-Technology Fit |

| IoT | Internet of Things | UB | Use Behavior |

| IU | Intention to Use a Technology | UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| IU | The Intention of Use | WTU | Willingness to Use |

| IV | Intrinsic Value | β | Path coefficients |

Appendix A

| Estimate | Std. Error | Lowbound | Upbound | z value | Pr(>|z|) | |

| AU on EE | 0.293149 | 0.040248 | 0.214265 | 0.372033 | 7.2837 | 3.249e-13 *** |

| AU on PE | 0.169997 | 0.061223 | 0.050002 | 0.289992 | 2.7767 | 0.0054917 ** |

| AU on PV | 0.242560 | 0.032734 | 0.178403 | 0.306717 | 7.4101 | 1.263e-13 *** |

| AU on SI | 0.150857 | 0.044516 | 0.063607 | 0.238107 | 3.3888 | 0.0007019 *** |

| EE on FC | 0.374236 | 0.035246 | 0.305156 | 0.443316 | 10.6180 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| EE on SI | 0.437334 | 0.042322 | 0.354385 | 0.520283 | 10.3336 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| PE with FC | 0.618127 | 0.021354 | 0.576273 | 0.659981 | 28.9461 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| PV with FC | 0.629135 | 0.022312 | 0.585404 | 0.672866 | 28.1970 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| PE with PV | 0.543783 | 0.027304 | 0.490268 | 0.597299 | 19.9156 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| SI with PV | 0.540050 | 0.020028 | 0.500796 | 0.579304 | 26.9647 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| SI with FC | 0.425293 | 0.026239 | 0.373867 | 0.476720 | 16.2087 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| PE with SI | 0.574790 | 0.018721 | 0.538098 | 0.611482 | 30.7036 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| Goodness-of-fit indices: | Value |

| Sample size | 8934.0000 |

| Chi-square of the target model | 43.2121 |

| DF of the target model | 3.0000 |

| p-value of the target model | 0.0000 |

| Number of constraints imposed on "Smatrix" | 0.0000 |

| DF manually adjusted | 0.0000 |

| Chi-square of the independence model | 4776.8168 |

| DF of the independence model | 15.0000 |

| RMSEA | 0.0387 |

| RMSEA lower 95% CI | 0.0290 |

| RMSEA upper 95% CI | 0.0494 |

| SRMR | 0.0476 |

| TLI | 0.9578 |

| CFI | 0.9916 |

| AIC | 37.2121 |

| BIC | 15.9192 |

References

- Bozkurt, A., Educational Technology Research Patterns in the Realm of the Digital Knowledge Age. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020. 2020: p. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Burch, P. and N. Miglani, Technocentrism and social fields in the Indian EdTech movement: formation, reproduction and resistance. Journal of Education Policy, 2018. 33(5): p. 590-616. [CrossRef]

- Buabeng-Andoh, C., Exploring University students’ intention to use mobile learning: A research model approach. Education and Information Technologies, 2021. 26. [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, D. and O. Alismaiel, Examination of factors influencing the use of mobile learning system: An empirical study. Education and Information Technologies, 2019. 23: p. 1-25.

- Silva, A. and D. Garzón, Identifying the Cognitive and Digital Gap in Educational Institutions Using a Technology Characterization Software. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments, 2023. 13: p. 1-12.

- Hennessy, S., et al., Technology Use for Teacher Professional Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Computers and Education Open, 2022. 3: p. 100080. [CrossRef]

- Madni, H., et al., Factors Influencing the Adoption of IoT for E-Learning in Higher Educational Institutes in Developing Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022. 13: p. 915596.

- Saleh, S., M. Nat, and M. Aqel, Sustainable Adoption of E-Learning from the TAM Perspective. Sustainability, 2022. 14: p. 3690. [CrossRef]

- Ali, J., et al., IoT Adoption Model for E-Learning in Higher Education Institutes: A Case Study in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 2023. 15: p. 9748. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N., et al., Blockchain Technology Adoption in Smart Learning Environments. Sustainability, 2021. 13. [CrossRef]

- Yip, K., et al., Adoption of mobile library apps as learning tools in higher education: a tale between Hong Kong and Japan. Online Information Review, 2020. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Alsswey, A., et al., M-learning technology in Arab Gulf countries: A systematic review of progress and recommendations. Education and Information Technologies, 2020. 25(4): p. 2919-2931. [CrossRef]

- Bice, H. and H. Tang, Teachers’ beliefs and practices of technology integration at a school for students with dyslexia: A mixed methods study. Education and Information Technologies, 2022. 27(7): p. 10179-10205. [CrossRef]

- Zaineldeen, S., et al., Technology Acceptance Model' Concepts, Contribution, Limitation, and Adoption in Education. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 2020. 8: p. 5061-5071.

- Venkatesh, V. and F. Davis, A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Management Science, 2000. 46: p. 186-204. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., et al., User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 2003. 27: p. 425-478.

- Blut, M., et al., Meta-Analysis of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): Challenging its Validity and Charting a Research Agenda in the Red Ocean. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 2022. 23: p. 13-95. [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K., et al., The extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): A systematic literature review and theory evaluation. International Journal of Information Management, 2020. 57: p. 102269. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. and H. Bala, Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decision Sciences - DECISION SCI, 2008. 39: p. 273-315. [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S. and M.M. Al-Debei, The determinants of Gen Z's metaverse adoption decisions in higher education: Integrating UTAUT2 with personal innovativeness in IT. Education and Information Technologies, 2024. 29(6): p. 7413-7445. [CrossRef]

- Wiangkham, A. and R. Vongvit, Exploring the Drivers for the Adoption of Metaverse Technology in Engineering Education using PLS-SEM and ANFIS. Education and Information Technologies, 2023. 29. [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A., et al., Extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict University Students’ Intentions to Use Metaverse-Based Learning Platforms. Education and Information Technologies, 2023. 28. [CrossRef]

- Koutromanos, G., et al., The mobile augmented reality acceptance model for teachers and future teachers. Education and Information Technologies, 2023. 29: p. 1-39.

- Chatterjee, S. and K. Bhattacharjee, Adoption of artificial intelligence in higher education: a quantitative analysis using structural equation modelling. Education and Information Technologies, 2020. 25. [CrossRef]

- Saif, N., et al., Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector via ubiquitous learning mechanism. Computers in Human Behavior, 2024. 154: p. 108097. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T., et al., Investigating teachers’ adoption of MOOCs: the perspective of UTAUT2. Interactive Learning Environments, 2019. 30: p. 1-16. 30: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A., et al., Acceptance and use of ChatGPT in the academic community. Education and Information Technologies, 2024. 29(17): p. 22943-22968. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., Participant or spectator? Comprehending the willingness of faculty to use intelligent tutoring systems in the artificial intelligence era. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2020. 51. [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A., To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students' acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 2024. 32: p. 5142-5155. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y., Y.-S. Wang, and S.-E. Jian, Investigating the Determinants of Students’ Intention to Use Business Simulation Games. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 2019. 58: p. 073563311986504. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y. and Y.-W. Chuang, Investigating the potential adverse effects of virtual reality-based learning system usage: from UTAUT2 and PPVITU perspectives. Interactive Learning Environments, 2023. 32: p. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Unal, E. and A. Uzun, Understanding university students’ behavioral intention to use Edmodo through the lens of an extended technology acceptance model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2020. 52. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-W. and Y.-C. Lai, User acceptance model of computer-based assessment: moderating effect and intention-behavior effect. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 2019. 35. [CrossRef]

- Bazelais, P., G. Binner, and T. Doleck, Examining the key drivers of student acceptance of online labs. Interactive Learning Environments, 2022. 32: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L., G. Widarso, and H. Sutrisno, A ChatBot for Learning Chinese: Learning Achievement and Technology Acceptance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 2020. 58: p. 073563312092962. [CrossRef]

- Bilquise, G., S. Ibrahim, and S.E. Salhieh, Investigating student acceptance of an academic advising chatbot in higher education institutions. Education and Information Technologies, 2023. 29: p. 1-26. [CrossRef]

- Estriégana, R., J. Medina, and R. Barchino, Student acceptance of virtual laboratory and practical work: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Computers & Education, 2019. 135. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A., A. Pack, and E. Quaid, Understanding learners’ acceptance of high-immersion virtual reality systems: Insights from confirmatory and exploratory PLS-SEM analyses. Computers & Education, 2021. 169: p. 104214. [CrossRef]

- Khechine, H., B. Raymond, and M. Augier, The adoption of a social learning system: Intrinsic value in the UTAUT model. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2020. 51. [CrossRef]

- Jung, I. and J. Lee, A cross-cultural approach to the adoption of open educational resources in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2019. 51. [CrossRef]

- Saidu, M.K. and M.A. Al Mamun, Exploring the Factors Affecting Behavioural Intention to Use Google Classroom: University Teachers’ Perspectives in Bangladesh and Nigeria. TechTrends, 2022. 66(4): p. 681-696.

- Teng, Z., et al., Factors Affecting Learners’ Adoption of an Educational Metaverse Platform: An Empirical Study Based on an Extended UTAUT Model. Mobile Information Systems, 2022. 2022: p. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Abbad, M., Using the UTAUT model to understand students’ usage of e-learning systems in developing countries. Education and Information Technologies, 2021. 26. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z. and W. Huang, A meta-analysis of mobile learning adoption using extended UTAUT. Information Development, 2023: p. 026666692311764. [CrossRef]

- Yakubu, N. and S. Dasuki, Factors affecting the adoption of e-learning technologies among higher education students in Nigeria: A structural equation modelling approach. Information Development, 2018. 35: p. 026666691876590.

- Yadegaridehkordi, E., et al., Predicting the Adoption of Cloud-Based Technology Using Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process and Structural Equation Modeling Approaches. Applied Soft Computing, 2018. 66. [CrossRef]

- Miah, M., J. Singh, and M. Rahman, Factors Influencing Technology Adoption in Online Learning among Private University Students in Bangladesh Post COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 2023. 15: p. 3543. [CrossRef]

- Duong, D., How effort expectancy and performance expectancy interact to trigger higher education students’ uses of ChatGPT for learning. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 2023. 21.

- Amrozi, Y., et al., Adoption of Information Technology as a Mediator Between Institutional Pressure and Change Performance. Journal of Namibian Studies : History Politics Culture, 2023. 34. [CrossRef]

- He, L. and C. Li, Students’ Adoption of ICT Tools for Learning English Based on Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Asian Journal of Education and Social Studies, 2023. 44: p. 26-38. [CrossRef]

- Sofwan, M., A. Habibi, and M. Yaakob, TPACK’s Roles in Predicting Technology Integration during Teaching Practicum: Structural Equation Modeling. Education Sciences, 2023. 13: p. 448. [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, A., et al., Social media usage and acceptance in higher education: A structural equation model. Frontiers in Education, 2022. 7. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K., et al., Re-examining the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): Towards a Revised Theoretical Model. Information Systems Frontiers, 2019. 21(3): p. 719-734. [CrossRef]

- Meet, R.K., D. Kala, and A.S. Al-Adwan, Exploring factors affecting the adoption of MOOC in Generation Z using extended UTAUT2 model. Education and Information Technologies, 2022. 27(7): p. 10261-10283. [CrossRef]

- Chomunorwa, S. and V. Mugobo, Challenges of e-learning adoption in South African public schools: Learners’ perspectives. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 2023. 10: p. 80-85. [CrossRef]

- Jak, S. and M. Cheung, Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling With Moderating Effects on SEM Parameters. Psychological Methods, 2019. 25. [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. and C. Gündüzalp, A unified framework for understanding teachers’ adoption of robotics in STEM education. Education and Information Technologies, 2023. 29: p. 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H., P. Singh, and D. Sharma, Faculty acceptance of virtual teaching platforms for online teaching: Moderating role of resistance to change. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 2023: p. 33-50. [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A., To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students' acceptance and use of technology. Interactive Learning Environments, 2023: p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Guggemos, J., S. Seufert, and S. Sonderegger, Humanoid robots in higher education: Evaluating the acceptance of Pepper in the context of an academic writing course using the UTAUT. British Journal of Educational Technology, 2020. 51. [CrossRef]

- Ustun, A.B., et al., Development of UTAUT-based augmented reality acceptance scale: a validity and reliability study. Education and Information Technologies, 2024. 29(9): p. 11533-11554. [CrossRef]

- Kashive, N. and D. Phanshikar, Understanding the antecedents of intention for using mobile learning. Smart Learning Environments, 2023. 10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., J.C.-Y. Sun, and S.-K. Chen, Comparing technology acceptance of AR-based and 3D map-based mobile library applications: a multigroup SEM analysis. Interactive Learning Environments, 2023. 31(7): p. 4156-4170. [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S., Factors influencing student teachers’ intention to use mobile augmented reality in primary science teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 2024. 29: p. 15353-15374. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S., et al., Examining students' intention to use ChatGPT: Does trust matter? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 2023. 39: p. 51-71.

- Cheung, M. and S.F. Cheung, Random-effects models for meta-analytic structural equation modeling: review, issues, and illustrations. Research Synthesis Methods, 2016. 7: p. 140-155.

- Cheung, M., Fixed- and random-effects meta-analytic structural equation modeling: Examples and analyses in R. Behavior research methods, 2013. 46. [CrossRef]

- Goretzko, D., K. Siemund, and P. Sterner, Evaluating Model Fit of Measurement Models in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 2023. 84: p. 001316442311638. [CrossRef]

- Sova, R., C. Tudor, and C. Tartavulea, Artificial Intelligence Tool Adoption in Higher Education: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach to Understanding Impact Factors among Economics Students. Electronics, 2024. 13: p. 3632. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).