Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Molecular Analysis

2.2.1. RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

2.3. Fruit Phenotypic Assessments

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Relative Gene Expression in Fruit Flesh on Different Stage of Apple Fruit Ripening

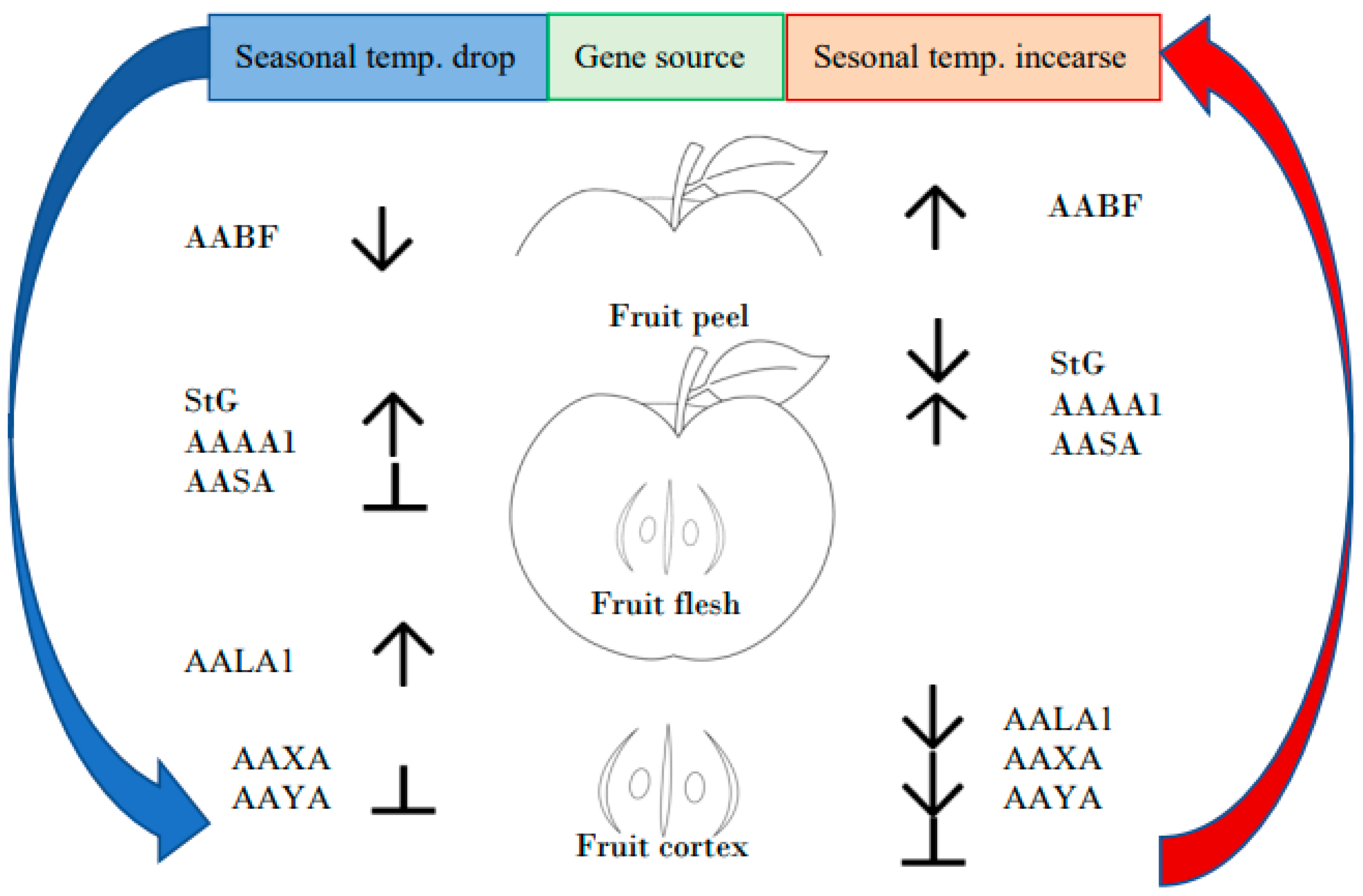

3.2. The Impact of Seasonal Temperature Changes on the Mechanism of Apple Fruit Development

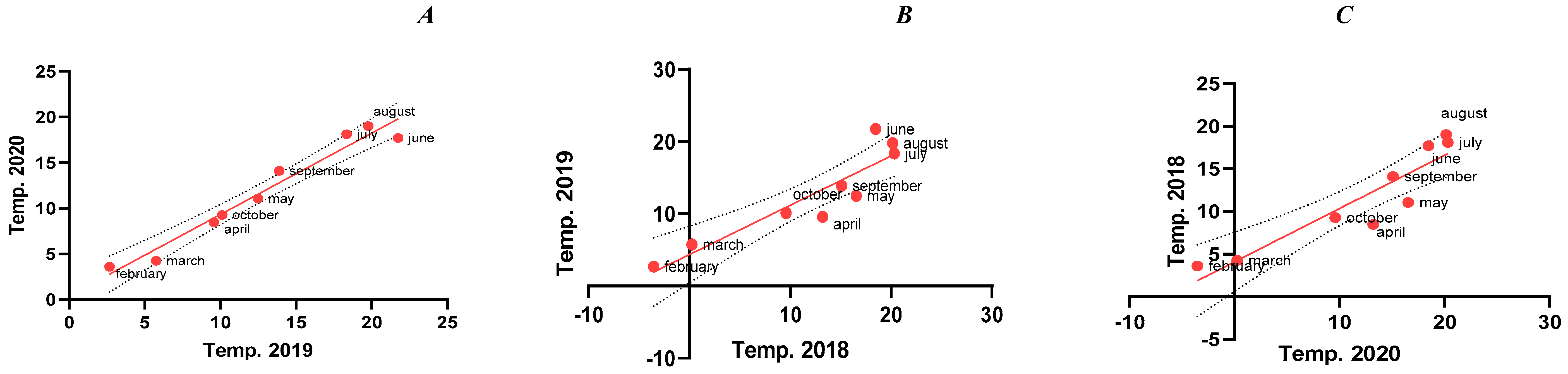

3.2.1. Relationship Between the Temperature Variations in Evaluated Growing Seasons

3.2.2. The Effect of the Seasonal Temperature Fluctuation on the Activity of Genes Employed in Apple Fruit Ripening Processes

3.2.3. Impact of the Seasonal Temperature Changes on the Apple Fruit Features

3.2.4. Correlation Between Gene Activities and the Values of Apple Fruit Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.-C.; Park, Y.-S.; Jeong, H.-N.; Kim, J.-H.; Heo, J.-Y. Temperature changes affected spring phenology and fruit quality of apples grown in high-latitude region of South Korea. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://300gospodarka.pl/.

- Ruchel, Q.; Zandona, R.R.; Fraga, D.S.; Agostinettop, D.; Langaro, A.C. Effect of high temperature and recovery from stress on Crop-Weed interaction. Bragantia 2020, 79, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller-Przybyłkowicz, S.; Lewandowski, M.; Korbin, M. Identification of the genome regions correlated with cold hardiness of apple rootstocks by transcriptomic analysis of differentially expressed candidate genes. Biuletyn Instytutu Hodowli i Aklimatyzacji Roślin 2019, 286, 415–418. [Google Scholar]

- Łysiak, G.P.; Szot, I. The Use of Temperature Based Indices for Estimation of Fruit Production Conditions and Risks in Temperate Climates. Agriculture 2023, 13, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysiak, G.P. Degree days as a method to estimate the optimum harvest date of ‘Conference’ pears. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łysiak, G. The sum of active temperatures as a method of determining the optimum harvest date of ‘S̆ampion’ and ‘Ligol’ apple cultivars. Acta Sci. Pol., Hortorum Cultus 2012, 11, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, M.V.; Lee, C.Y.; Liu, R.H. Antioxidant activity of fresh apples. Nature 2000, 405, 903–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyson, A.D. A Comprehensive Review of Apples and Apple Components and Their Relationship to Human Health. Advances in Nutrition 2011, 2, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyenihi, A.B.; Belay, Z.A.; Mditshwa, A.; Caleb, O.J. “An apple a day keeps the doctor away”: The potentials of apple bioactive constituents for chronic disease prevention. Journal of Food Science 2022, 87, 2291–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller-Przybyłkowicz, S.E.; Rutkowski, K.P.; Kruczyńska, D.E.; Pruski, K. Changes in gene expression profile during fruit development determine fruit quality. Hort. Sci (Prague) 2016, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, P.; Brown, S.; Weeden, N. Molecular-marker analysis of quantitative traits for growth and development in juvenile apple trees. Theor Appl Genet 1998, 96, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cãtãlina, D.; Adriana, S.; Bozdog, C.; Radu, S. Estimation of genetic effects implied in apple inheritance of quantitative traits. J. Hortic. Forestry Biotechnol 2015, 19, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shen, F.; Wang, W.; Wu, B.; Wang, X.; Xiao, C.; Tian, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Quantitative trait loci-based genomics-assisted prediction for the degree of apple fruit cover color. The Plant Genome 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Jiao, C.; Schwaninger, H.; et al. Phased diploid genome assemblies and pan-genomes provide insights into the genetic history of apple domestication. Nat Genet 2020, 52, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Molloy, C.; Muñoz, P.; Daetwyler, H.; Chagné, D.; Volz, R. Genome-enabled estimates of additive and nonadditive genetic variances and prediction of apple phenotypes across environments. G3 2015, 5, 2711–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wen, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Liao, Y. Mulching practices altered soil bacterial community structure and improved orchard productivity and apple quality after five growing seasons. Scientia Horticulturae 2014, 172, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, N. Research progress on genetic basis of fruit quality traits in apple (Malus x domestica). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cãpraru, F.; Zlati, C. Observations regarding yield phenophases of some diseases genetic resistant apple cultivars, in the conditions of Bistrita Region. Horticulturã 2009, 539–544. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, J.F. and Neven, L.G. Physiological Development Time and Zero Development Temperature of the Codling Moth (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Environmental Entomology 2000, 29, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayd, S.E.; Tarara, J.M.; Mee, D.L.; Ferguson, J.C. Separation of Sunlight and temperature Effects on the Composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot Berrie. Am. J. Enol. Vitic 2002, 53, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, A.; Estrella, N.; Fabian, P. Spatial and temporal variability of the phenological seasons in Germany from 1951 to 1996. Global Change Biology 2001, 7, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gian-Reto, W. Plants in a warmer world. Perspectives in Plant Ecology. Evolution and Systematics 2003, 6/3, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Logan, J.; Coffey, D.L. Mathematical formulae for calculation the base temperature for growing degree days. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 1995, 74, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, B.J.; Thodey, K.; Schaffer, R.J.; Alba, R.; Balakrishman, L.; Bishop, R.; Bowen, J.H.; Crowhurst, R.N.; Gleave, A.P.; Ledger, S.; McArtney, S.; Pichler, F.B.; Snowden, K.C.; Ward, S. Global gene expression analysis of apple fruit development from the floral bud to ripe fruit. BMC Plant Biology 2008, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudolf, V.; Vlieghe, K.; Beemster, G.T.; Magyar, Z.; Torres Acosta, J.A.; Maes, S.; Van Der Schueren, E.; Inze, D.; De Veylder, L. The plant-specific cyclin-dependent kinase CDKB1;1 and transcription factor E2Fa-DPa control the balance of mitotically dividing and endoreduplicating cells in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004, 16, 2683–2692. [Google Scholar]

- Dewitte, W.; Murray, J.A. The plant cell cycle. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003, 54, 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- Spruck, C.; Strohmaier, H.; Watson, M.; Smith, A.P.; Ryan, A.; Krek, T.W.; Reed, S.I. A CDK-independent function of mammalian Cks1: targeting of SCF(Skp2) to the CDK inhibitor p27Kip1. Mol Cell 2001, 7, 639–650. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; Fernández, V.; Val, J. Improving the performance of calcium-containing spray formulations to limit the incidence of bitter pit in apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.). Scientia Horticulturae 2010, 127, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Feng, F.; Cheng, L. Expression patterns of genes involved in sugar metabolism and accumulation during apple fruit development. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33055. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Yang, T. RNA Isolation from Highly Viscous Samples Rich in Polyphenols and Polysaccharides. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2002, 20, 417. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta DeltaC(T)). Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Warrington, I.J.; Fulton, T.A.; Halligan, E.A.; de Silva, H.N. Apple Fruit Growth and Maturity Are Affected by Early SeasonTemperatures. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 124, 468–477. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, R.; Zharkikh, A.; Affourtit, J.; et al. The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Nat Genet 2010, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonius-Klemola, K.; Kalendar, R.; Schulman, A.H. TRIM retrotransposons occur in apple and are polymorphic between varieties but not sports. Theor Appl Genet. 2006, 112, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Korban, S.S. Spring: a novel family of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements is associated with genes in apple. Genomics 2007, 90, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.K. Pome fruit breeding: progress and prospects. Acta Hort. 2003, 622, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Telias, A.; Lin-Wang, K.; Stevenson, D.E.; Cooney, J.M.; Hellens, R.P.; Allan, A.C.; Hoover, E.E.; Bradeen, J.M. Apple skin patterning is associated with differential expression of MYB10. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Feschotte, C. Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nature Rev Genetics 2008, 9, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, D.L. and Bull, V. The effect of summer temperature on flower initiation and fruit bud development. Annual Report of Long Ashton Research Station 1973, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, H.; Ohmura, H.; Arai, C.; Terui, M. Effect of preharvest fruit temperature on ripening sugars, and watercore occurrence in apples. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1994, 119, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Dougherty, L.; Cheng, L.; Xu, K. A co-expression gene network associated with developmental regulation of apple fruit acidity. Mol Genet Genomics 2015, 290, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Han, Y. Genomics of fruit acidity and sugar content in apple. In Apple Genome; Korban, S.S., Ed.; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2021; pp. 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, L.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Zheng, P.-F.; Wang, C.-K.; Wang, X.; Li, H.-L.; Liu, G.-D.; Liu, R.-X.; Wang, X.-F.; You, C.-X. Genome-Wide analysis of MdABF subfamily and functional identification of MdABF1 in drought tolerance in apple. Science Direct 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Sun, D.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, T. Expression of flavonoid biosynthesis genes and accumulation of flavonoid in wheat leaves in response to drought stress, Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Musacchi, S.; Serra, S. Review: apple fruit quality: overview on pre-harvest factors. J. Sci. Hortic 2018, 234, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.A.T.; Stridh, H.; Molin, M. Influence of weather conditions on the quality of ‘Ingrid Marie’ apples and their susceptibility to grey mould infection. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, O.M.; Rivero, R.; Sønsteby, A. Temperature control of shoot growth and floral initiation in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). CABI Agric Biosci 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydlik, Z.; Kayzer, D.; Zydlik, P. The influence of some climatic conditions on the yield and fruit of replanted apple orchard. Pol. J. Environ. Study. 2023, 33, 4493–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagné, D.; Daya Dayatilake, D.; Diack, R.; Murray, O.; Ireland, H.; Watson, A.; Gardiner, S.E.; Johnston, J.W.; Schaffer, R.J.; Tustin, S. Genetic and environmental control of fruit maturation, dry matter and firmness in apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Horticulture Research 2014, 1, 14046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Season/year 2018 | Season/year 2019 | Season/year 2020 | |||||||||||||

| Apple cv. | FB* | I | II | III | IV | FB* | I | II | III | IV | FB* | I | II | III | IV |

| ‘Ligol’ | 30.04 | 12.09 | 17.09 | 22.09 | 27.09 | 2.05 | 11.09 | 16.09 | 21.09 | 26.09 | 1.05 | 10.09 | 15.09 | 20.09 | 25.09 |

| ‘Pink Braeburn’ | 2.05 | 17.09 | 21.09 | 26.09 | 01.10 | 3.05 | 16.09 | 20.09 | 25.09 | 30.09 | 3.05 | 16.09 | 20.09 | 25.09 | 30.09 |

| ‘Pinokio’ | 3.05 | 16.09 | 20.09 | 25.09 | 30.09 | 5.05 | 18.09 | 23.09 | 27.09 | 2.10 | 4.05 | 19.09 | 22.09 | 26.09 | 01.10 |

| ‘Ligolina’ | 6.05 | 20.09 | 25.09 | 30.09 | 4.10 | 8.05 | 22.09 | 27.09 | 02.10 | 07.10 | 6.05 | 20.09 | 25.09 | 30.09 | 4.10 |

| Gen | Sequence ID/gene function and location | Oligo Forward | Oligo Revers |

| StG | EE663791 Starch glucosilase | atctcctcgcatcaacaac | agaagacggagagcagacca |

| AAAA1 | 020403AAAA006503CR/(AAAA) fruits of Royal Gala, 59 DAFB, seeds removed, M. domestica clone cDNA AAAAA00650, mRNA | cattcccggcaatcttacaaac | gaccagtcaccatcccaaat |

| AAFB | 020815AAFB001404CR/(AAFB) Royal Gala, apple skin peel, 150 DAFB M. domestica clone cDNA AAFB 00140, s mRNA | ggccgtagaatttccacatttc | acaacaatctcacaggtcctatac |

| AALA1 | 020208AALA001579CR/(AALA) Royal Gala 150 DAFB fruit cortex M. domestica clone cDNA AALAA00157, mRNA | caacaacgggaccagagataa | agcaggtttgagaagaaggg |

| AASA | 020514AASA003901CO/(AASA) Royal Gala 10 DAFB fruit M. domestica cDNA clone AASAA00390, mRNA | cggcaagaagtcaatgaagaac | tcccagaaccagagttgaaag |

| AAYA | 020308AAYA001283CR/(AAYA) Royal Gala 126 DAFB fruit cortex M. domestica clone cDNA AAYAA00128, mRNA | gatccatgaactcgtcgttga | cagggttcggacagaaagaa |

| AAAA2 | 030210AAAA009549CR/(AAAA) Royal Gala fruits 59 DAFB, seeds removed M. domestica clone cDNA AAAAA00954, mRNA | ggaagaacaggcttgctttg | aaatgacgtcccttcgctatta |

| AAXA | 021203AAXA001589CO/(AAXA) Royal Gala 126 DAFB fruit core M. domestica clone cDNA AAXAA00158, mRNA | ggcgactccaatacgatgaa | actgatgcagaatccacagag |

| Analysis of Variance | 2019 vs. 2020 | 2018 vs. 2019 | 2018 vs. 2020 | ||||||||||||

| SS | DF | MS | F | p value | SS | DF | MS | F | p value | SS | DF | MS | F | p value | |

| Regression | 507.1 | 2 | 253.6 | 17.40 | p = 0.0032 | 263.4 | 2 | 131.7 | 74.59 | p < 0.0001 | 317 | 2 | 158.5 | 70.17 | p < 0,0001 |

| R squared (R2)* | 0.853 | 0.9613 | 0.959 | ||||||||||||

| Difference between means | 0.9674 | −0.4753 | 0.4921 | ||||||||||||

| SE of difference | 0.4649 | 1.254 | 1.319 | ||||||||||||

| temp −1,6 vs. 14,9 °C | temp −1,6 vs. 19,4 °C | temp −1,6 vs. 17,7 °C | temp 14,9 vs. 19,4 °C | temp 14,9 vs. 17,7 °C | temp 19,4 vs. 17,7 °C | ||||||||

| gene | Difference |

SE of difference |

Difference |

SE of difference |

Difference |

SE of difference |

Difference |

SE of difference |

Difference |

SE of difference |

Difference |

SE of difference |

|

| Pinokio | STG | 113 | 28,87 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 5,669 | 0,55 | −92 | 8,78 | −97,69 | 8,777 |

| AAAA1 | 17,2 | 4,01 | −3,1 | 0,5 | −109 | 4,7 | −3,7 | 0,22 | −110 | 4,68 | 46,97 | 1,844 | |

| AAFB | −33 | 0,81 | −36 | 1,3 | −55 | 1,67 | ns | ns | −22 | 1,85 | −18,33 | 2,122 | |

| AALA1 | 17,2 | 4,01 | ns | ns | −646 | 19,07 | −35 | 1,32 | −664 | 18,6 | −628,7 | 18,69 | |

| AASA | 23,6 | 2,18 | 21,2 | 2,2 | −640 | 6,6 | −2,36 | 0,35 | −664 | 6,23 | −661,5 | 6,235 | |

| AAYA | −1,4 | 0,054 | ns | ns | −1,2 | 0,044 | 0,895 | 0,22 | ns | ns | −0,687 | 0,2166 | |

| AAAA2 | 1,78 | 0,26 | ns | ns | 2,02 | 0,176 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| AAXA | 19,8 | 3,46 | 17,2 | 3,5 | ns | ns | −2,64 | 0,18 | −19 | 1,03 | −16,36 | 1,043 | |

| Ligolina | STG | 22,8 | 0,985 | −199 | 11 | 22,8 | 0,986 | −222 | 11,1 | 221,7 | 11,12 | ||

| AAAA1 | 54,2 | 0,155 | 7,57 | 1,8 | 54,5 | 0,162 | −46,6 | 1,84 | 0,4 | 0,08 | 23,63 | 1,896 | |

| AAFB | −95 | 2,297 | −21 | 1,9 | 73,93 | 2,96 | 96 | 2,28 | 22,17 | 1,896 | |||

| AALA1 | −3,7 | 0,39 | −23 | 1,9 | 0,94 | 0,034 | −19 | 1,93 | 4,6 | 0,39 | 23,63 | 1,896 | |

| AASA | 684 | 29,43 | 616 | 32 | 689 | 29,43 | −68,7 | 12,2 | ns | ns | 73,24 | 12,24 | |

| AAYA | 1,49 | 0,09 | ns | ns | ns | ns | −1,92 | 0,14 | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| AAAA2 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | −0,7 | 0,15 | ns | ns | |

| AAXA | 257 | 6,56 | 202 | 10 | 258 | 6,561 | −54,4 | 8,02 | 0,9 | 0,13 | 55,32 | 8,023 | |

| Ligol | STG | 26,3 | 3,84 | 40,9 | 3,7 | 36,7 | 3,674 | 14,59 | 1,12 | 10 | 1,12 | −4,145 | 0,0372 |

| AAAA1 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | −1,09 | 0,05 | −1,1 | 0,01 | ns | ns | |

| AAFB | −1,1 | 0,07 | −1 | 0 | −10 | 1,45 | ns | ns | −9 | 1,45 | −9,154 | 1,45 | |

| AALA1 | 136 | 29,45 | 136 | 29 | 136 | 29,45 | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| AASA | ns | ns | ns | ns | −2,1 | 0,25 | ns | ns | −1,3 | 0,25 | −1,501 | 0,139 | |

| AAYA | 1,28 | 0,23 | −5,3 | 0,3 | 1,68 | 0,17 | −6,55 | 0,32 | ns | ns | 6,945 | 0,285 | |

| AAAA2 | −0,8 | 0,06 | −3,5 | 0,5 | −2,8 | 0,19 | −2,75 | 0,53 | −2 | 0,2 | ns | ns | |

| AAXA | 257 | 6,56 | 202 | 10 | 258 | 6,561 | −54,4 | 8,02 | 0,9 | 0,13 | 55,32 | 8,023 | |

| Pink Braeburn | STG | −28 | 2,364 | −1,3 | 0,2 | −62 | 1,009 | 26,41 | 2,37 | −34 | 2,57 | −60,7 | 1,03 |

| AAAA1 | −51 | 6,137 | −27 | 1,8 | −1 | 0,035 | 23,61 | 6,41 | 50 | 6,14 | 26,14 | 1,84 | |

| AAFB | −223 | 34,7 | −2,2 | 0,1 | −1,2 | 0,082 | 221,2 | 34,7 | 222 | 34,7 | 1,019 | 0,103 | |

| AALA1 | 179 | 2,884 | 178 | 2,9 | 176 | 2,89 | −1,11 | 0,08 | −3 | 0,17 | −1,931 | 0,177 | |

| AASA | −151 | 4,321 | −3,8 | 0,1 | −1 | 0,092 | 146,8 | 4,32 | 150 | 4,32 | 2,88 | 0,16 | |

| AAYA | 4,86 | 0,13 | 6,07 | 0 | 6,17 | 0,061 | 1,217 | 0,12 | 1,3 | 0,13 | ns | ns | |

| AAAA2 | 0,56 | 0,085 | 1,48 | 0,1 | 1,44 | 0,091 | 0,912 | 0,01 | 0,9 | 0,03 | ns | ns | |

| AAXA | −40 | 5,26 | −5,1 | 0,2 | −2,3 | 0,107 | 35,34 | 5,26 | 38 | 5,26 | 2,741 | 0,207 | |

| cv. | Trait assesment | 2018 vs. 2019 | 2018 vs. 2020 | 2019 vs. 2020 | |||

| Effect | SE | Effect | SE | Effect | SE | ||

| Ligol | FW | ns | ns | −65,85 | 11,85 | −95,79 | 10,75 |

| IEC | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| TSS | −1,51 | 0,4013 | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| TA | −0,1912 | 0,03057 | −0,1123 | 0,01942 | ns | ns | |

| FF | −16,24 | 2,407 | −7,331 | 2,13 | ns | ns | |

| Pink Braeburn | FW | 46,36 | 4,687 | −58,89 | 17,7 | −105,3 | 18,26 |

| IEC | −9,873 | 2,374 | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| TSS | −1,535 | 0,2852 | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| TA | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| FF | −10,53 | 2,364 | −7,884 | 1,801 | |||

| Pinokio | FW | 91,55 | 15,47 | ns | ns | −99,17 | 10,84 |

| IEC | −12,25 | 1,626 | ns | ns | 11,02 | 2,039 | |

| TSS | −1,338 | 0,4316 | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| TA | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| FF | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Ligolina | FW | 76,29 | 14,03 | ns | ns | −90,64 | 12,99 |

| IEC | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| TSS | 0,8107 | 0,228 | 0,7883 | 0,1998 | ns | ns | |

| TA | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| FF | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | |

| Apple cv. | Trait | StG | AAAA1 | AAFB | AALA1 | AASA | AAYA | AAAA2 | AAXA |

| Ligol | FW | 0,93**** | 0,94**** | 0,94**** | 0,79**** | 0,94**** | 0,94**** | 0,94**** | 0,94**** |

| IEC | 0,32** | 0,08 | 0,15 | 0,13 | 0,22* | 0,52**** | 0,46*** | 0,12 | |

| TSS | 0,04 | 0,97**** | 0,65**** | 0,07 | 0,97**** | 0,72**** | 0,93**** | 0,93**** | |

| TA | 0,32** | 0,15 | 0,15 | 0,13 | 0,42*** | 0,55**** | 0,55**** | 0,16 | |

| FF | 0,78**** | 0,97**** | 0,96**** | 0,09 | 0,97**** | 0,97**** | 0,97**** | 0,97**** | |

| Pink Braeburn | FW | 0,84**** | 0,85**** | 0,44*** | 0,58**** | 0,66**** | 0,90**** | 0,90**** | 0,87**** |

| IEC | 0,20* | 0,17* | 0,12 | 0,13 | 0,12 | 0,08 | 0,19* | 0,07 | |

| TSS | 0,10 | 0,06 | 0,09 | 0,09 | 0,08 | 0,85**** | 0,98**** | 0,0003 | |

| TA | 0,29** | 0,28** | 0,14 | 0,15 | 0,15 | 0,30** | 0,61**** | 0,19* | |

| FF | 0,59**** | 0,70**** | 0,006 | 0,035 | 0,09 | 0,98**** | 0,99**** | 0,83**** | |

| Pinokio | FW | 0,53**** | 0,02 | 0,78**** | 0,0006 | 0,0001 | 0,86**** | 0,86**** | 0,84**** |

| IEC | 0,31** | 0,14 | 0,46*** | 0,17* | 0,15 | 0,12 | 0,09 | 0,15 | |

| TSS | 0,25* | 0,13 | 0,33** | 0,15 | 0,14 | 0,98**** | 0,97**** | 0,003 | |

| TA | 0,34** | 0,14 | 0,56**** | 0,17* | 0,16 | 0,74**** | 0,65**** | 0,40*** | |

| FF | 0,002 | 0,088 | 0,52**** | 0,082 | 0,073 | 0,98**** | 0,98**** | 0,91**** | |

| Ligolina | FW | 0,31** | 0,78**** | 0,71**** | 0,86**** | 0,007 | 0,87**** | 0,87**** | 0,20* |

| IEC | 0,18* | 0,34** | 0,24* | 0,21* | 0,18* | 0,71**** | 0,86**** | 0,22* | |

| TSS | 0,12 | 0,13 | 0,11 | 0,12 | 0,16* | 0,98**** | 0,99**** | 0,17* | |

| TA | 0,18* | 0,34** | 0,24* | 0,20* | 0,18* | 0,65**** | 0,82**** | 0,22* | |

| FF | 0,001* | 0,54**** | 0,27** | 0,94**** | 0,09 | 0,99**** | 0,99**** | 0,009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).