1. Introduction

Synchrotron radiation is electromagnetic radiation emitted by charged particles moving near the speed of light along an arc in a magnetic field [

1]. The X-ray beam produced by synchrotron radiation has unique and great qualities such as strong stability, high flux, and quasi-coherence, which offer technological benefits in biomedicine, electronic devices, aviation industry materials, and other fields. The research depth and scope of global synchrotron radiation source facilities have been expanding since their inception in 1947. There are more than 50 devices in use or being built after four generations of development. The Super Photon Ring-8 GeV (SPring-8), the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), and the Advanced Photon Source (APS) are examples of third-generation light sources that have been planned and developed sequentially since the 1990s. These sources are still operating steadily and maintaining high-quality output, which demonstrates the long-term viability of those large-scale research facilities [

2]. There is a broad trend toward updating current facilities and constructing new 4th generation synchrotron sources, such as MAX IV in Sweden, Sirius in Brazil, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility Extremely Brilliant Source (ESRF-EBS) in France [

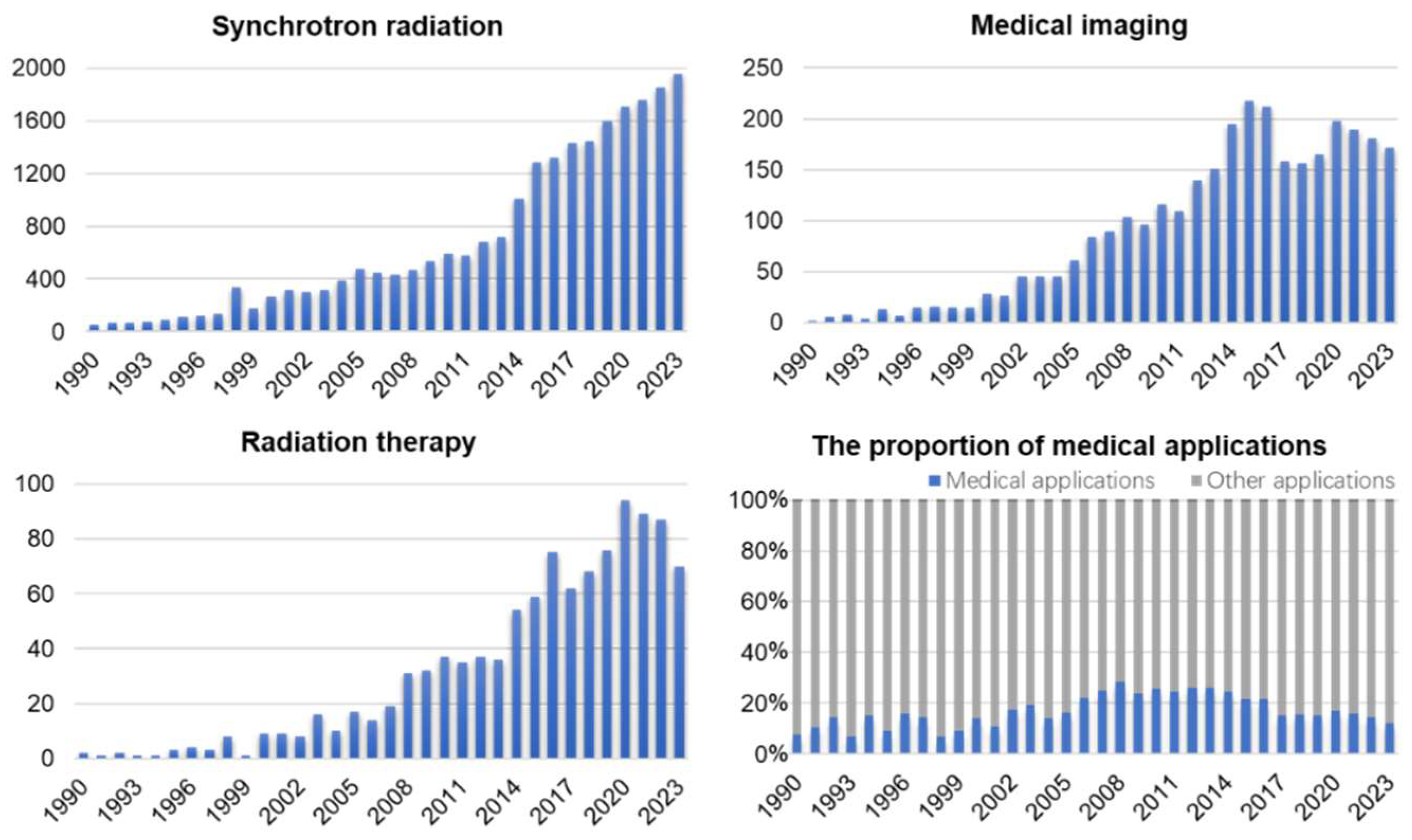

3]. In China, the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF), Hefei Light Source (HLS), Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), Taiwan Synchrotron Radiation Facility (TLS), and Taiwan Photon Source (TPS) are all ranked in the middle-low-energy region, and the high-energy light source (High Energy Photon Source, HEPS) with energy exceeding 40 keV is currently under construction. Biomedical applications for medical imaging and radiotherapy are an important part of synchrotron radiation light sources. In terms of imaging, based on the coherence and monochromaticity of synchrotron radiation beams, the capacity of X-ray phase-contrast imaging (PCI) to extract electron density pictures enhances contrast and resolution of imaging results significantly. In radiotherapy, the synchrotron radiation X-ray has a higher flux density than that of a conventional broadband beam. The beam with adjustable energy can accommodate the variations in X-ray absorption by various tissues. Synchrotron radiotherapy can ablate tumor tissues selectively in a more accurate, efficient, and responsible way. The consequence of fundamental scientific research and industrial application from synchrotron radiation has been developing progressively in recent years, as statistical results of PubMed Database reports (1990-2021) show (Fig.1). Compared with the 1990s, the scientific output by the year 2021 has expanded by more than 30 times (Fig.1A). Among these, both the research achievements in medical imaging and radiotherapy made possible by synchrotron radiation are favorably connected to the overall growth of the discipline, with an increasing tendency year after year (Fig.1B and C). In addition, studies of medical applications have accounted for 15%-25% of synchrotron radiation applications since 2000. This shows that as people's living circumstances have improved, more stringent standards for the improvement of medical issues have been proposed. In the field of biological sciences, synchrotron radiation is gaining importance. In this review, we summarize the development of experimental stations for medical imaging and radiotherapy in synchrotron radiation facilities. Furthermore, we discuss the existing challenges in medical applications and speculate on their future potential.

Figure 1.

Outcome of synchrotron radiation research in medical imaging and radiotherapy (1990.1-2023.12). (A) Synchrotron radiation. (B) Medical imaging. (C) Radiation therapy. (D) the proportion of medical applications in synchrotron radiation. Data source: PubMed.

Figure 1.

Outcome of synchrotron radiation research in medical imaging and radiotherapy (1990.1-2023.12). (A) Synchrotron radiation. (B) Medical imaging. (C) Radiation therapy. (D) the proportion of medical applications in synchrotron radiation. Data source: PubMed.

2. Light Sources and Biomedical Beamlines

Several synchrotron-based biomedical beamlines have been constructed throughout the globe, which provide a high-quality research platform for improving the accuracy of disease diagnosis and promoting radiotherapy programs. At present, there are several well-established beamlines in synchrotron radiation facilities, including ESRF (ID17) in France, the Imaging and Medical Beamline (IMBL) in Australia, the BioMedical Imaging and Therapy (BMIT) in Canada, the Synchrotron Radiation for Medical Physics (SYRMEP) of Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste in Italy, BL20B2 of the Super Photon ring-8 GeV (SPring-8) in Japan, and 2-BM-A, B of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) in America, etc. Medical-related applications in beamlines are a significant component of synchrotron radiation facilities. It results in enhanced imaging performance due to the synchrotron radiation's X-ray monochromaticity and energy tunability.

Table 1 summarizes the technical characteristics of global active beamlines and their typical medical application cases. Different medical beamlines establish their own different advantageous imaging and therapeutic applications for diverse research items based on performance variances in beam energy, spot size, flux, and other parameters.

There are multiple areas of study at different stages in the field of medical applications utilizing synchrotron X-ray imaging (

Table 1). Breast cancer imaging, vascular imaging, and skeletal microstructure imaging are all in clinical trials. Preclinical trials have yielded encouraging results, and these procedures are currently being tested on human individuals. Synchrotron X-ray radiation treatment, on the other hand, is still in the animal model stage. This technique has shown promise for precise targeting cancer treatment, but further study is needed to assess its safety and efficacy in humans. Overall, synchrotron X-ray imaging techniques can potentially revolutionize medical diagnosis and therapy; however, further comprehensive research and clinical trials are needed to evaluate their potential benefits and safety completely.

3. Synchrotron X-Ray in Medical Imaging

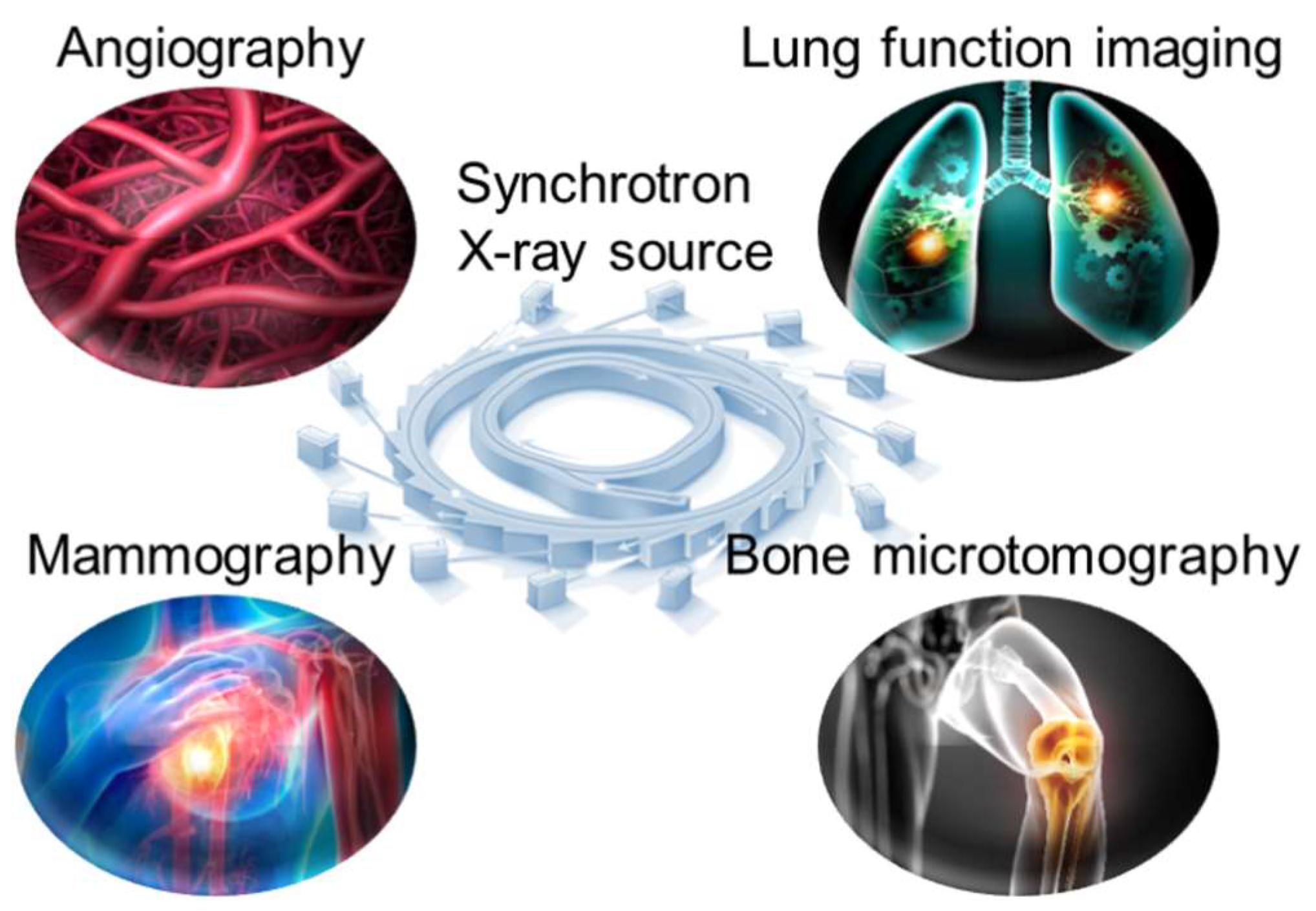

Traditional X-ray computed tomography (CT) has been widely used in the clinic for disease diagnostic imaging. However, the spectral breadth and intensity of an X-ray beam produced by a conventional source continue to restrict image quality. Photon absorption qualities differ in various human tissues, causing imaging errors. Correcting artifacts using complex mathematical models is one of the most challenging tasks in CT image reconstruction. It is, nevertheless, dependent on complicated algorithms and computational resources. When using synchrotron radiation-based CT imaging, these risks may not occur. When monochromatic synchrotron X-rays are used to irradiate tissue, only the intensity varies. As a result, it successfully avoids the problem of artifacts in medical imaging induced by X-ray beam hardening. Furthermore, the application of sophisticated data-gathering methods and reconstruction algorithms can greatly reduce the number of projections required for CT imaging, hence lowering radiation dosage. In recent years, medical imaging applications employing synchrotron radiation X-ray have expanded and made significant scientific progress. We describe recent practical applications of synchrotron X-ray in angiography, including angiography, lung function imaging, mammography, and bone microtomography (Fig.2)

Figure 2.

Common medical imaging applications of synchrotron X-ray source.

Figure 2.

Common medical imaging applications of synchrotron X-ray source.

3.1. Angiography

The X-ray utilized for clinical angiography is insufficient to provide a high-quality image directly, necessitating the administration of a large amount of agent (such as iodine), causing patients discomfort and radiation damage during imaging. Using synchrotron X-ray combination with the K-edge subtraction (KES) method, high-resolution angiographic images can be easily created with a modest amount of contrast agent and a low radiation dose [

28]. Usually, this process can be simply described as the following steps. After intravascular injection of low-dose iodine, two images can be recorded in sequence with X-ray beams of different energies: one is above the energy value of the absorption edge K of iodine element, while the other is slightly lower. Due to the absorption difference, the high contrast of vascular images can be obtained by subtracting the two images. Thus, the vessels can be distinguished and quantified. Coronary angiography is one of the few reported applications of synchrotron radiation in human bodies, and it can be used to diagnose diseases such as atherosclerosis [

29], arterial embolism [

30], and tumor angiogenesis [

31].

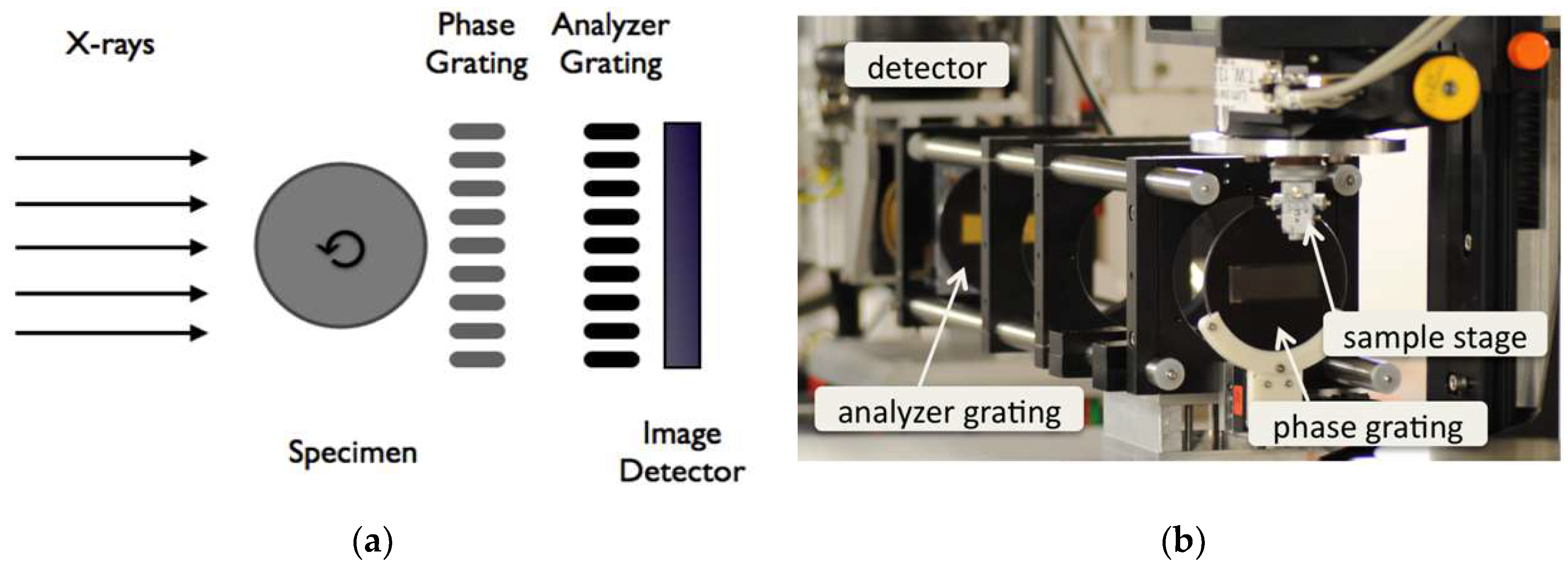

Figure 3 (A) and (B) shows the schematic drawing and photograph of the imaging set-up at the synchrotron beamline ID19, ESRF, France. (C) and (D) shows a comparison of angiographic images obtained from conventional and synchrotron X-rays. Finer structures (such as the intimal layer of distal external carotid artery) can be resolved by synchrotron X-ray imaging. Meanwhile, it can achieve very high-sensitivity detection with high-resolution images at low agent concentrations and radiation doses. Featured with low invasiveness, synchrotron X-ray coronary angiography has become a helpful technique for fundamental research of cardiovascular disease and its long-term follow-up monitoring after treatment. As a result, clinical trials of coronary angiography were conducted in the 1990s at SSRL (Stanford, USA), Hasylab (Hamburg, Germany), NSLS (Brookhaven, USA), ESRF (Grenoble, France), and KEK (Tsukuba, Japan), where approximately 500 volunteer patients were examined for this technology[

32,

33]. The results show that the sensitivity and resolution of cardiovascular imaging obtained by synchrotron X-ray are significantly improved from those of the conventional X-ray scheme, which avoids the problem of image artifacts caused by respiratory motion. The innovative approach on non-invasive and quick examination wins widespread acceptance among volunteer patients and clinicians. Additionally, tumor angiogenesis is a key feature of the progression of malignant tumors and serves as an essential marker for early detection of tumors, the study of tumorigenesis mechanism, and evaluation of curative effect [

34]. Synchrotron X-ray phase-contrast imaging offers a high spatial resolution up to the micron level and is also likely to be a valuable tool in the study of early-stage tumor angiogenesis. By using phase-contrast computed tomography, Xuan et al. achieved 3D visualization and morphological quantification of ex vivo liver fibrosis microvessels at different stages at SSRF's BL13W1 beamline [

35]. At present, a large number of anti-tumor angiogenesis drugs (such as axitinib, bevacizumab, cabozantinib, etc.) have been widely applied in the treatment of tumors [

36]. Synchrotron X-ray angiography offers a more accurate visualization method for clinical applications such as coronary disease, tumor microvascular identification, and antiangiogenic treatment efficacy evaluation.

3.2. Lung Function Imaging

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in both men and women, accounting for approximately 1.8 million deaths worldwide in 2020 [

37]. Early detection and therapy are critical to increasing lung cancer survival rates. However, the heterogeneity in lung structure and function makes it difficult to complete accurate detection by conventional physiological measurement methods. Based on experience with coronary angiography, the synchrotron X-ray KES method can also be applied to lung studies using xenon as a contrast agent [

38]. This method enables quantitative visualization of regional lung ventilation, assessment of lung morphology, inflammation, and biomechanics in high-resolution images. The KES technique can be used to image xenon during consecutive breaths and quantify the distribution of ventilation in specific regions. The lung ventilatory heterogeneity affects the matching of regional ventilation and perfusion, resulting in reduced gas exchange efficiency, and can significantly affect the apparent degree of mechanical lung obstruction, which is a pathological feature of many lung diseases [

39].

Figure 4A shows a schematic of the setup of lung imaging in synchrotron radiation beamline station for small animals [

40].

Figure 4B shows the lung images of rabbits allergic to ovalbumin after injection of acetylcholine and ovalbumin. The images show that acetylcholine mainly causes the contraction of the central airway in the control group, while more-uneven distribution of peripheral ventilation in the lung is visualized in the experimental group. It is caused by contracting the peripheral airway. In addition, phase contrast imaging can be used to improve the resolution of biological soft tissue imaging due to the high coherence of synchrotron X-rays. Phase contrast imaging visualizes structural details in the lungs to a resolution of 1μm, which is hard to achieve with conventional X-ray absorption contrast imaging. Walsh et al. [

41] successfully obtained high-resolution three-dimensional images of isolated lung tissue of COVID-19 patients (Fig.4C-4D) using hierarchical phase-contrast tomography (Hip-CT) on beamline BM05 (ESRF), from which the complex pulmonary vasculature could be assessed at micron-level. The new technology helps reveal the pathological changes caused by COVID-19 in tiny vessels in lungs. High-resolution imaging can visualize small lesions and provide opportunities for early intervention, improving greatly the recovery rate of lung cancer and the five-year survival rate of patients. At present, synchrotron X-ray imaging has been validated in animal models of different lung diseases and in vitro tissue studies, and feasible imaging schemes have been optimized, but it has not yet entered the clinical stage. The key restrictions are the minimal number of synchrotron radiation sources, the lag of medical imaging beamlines, and the uncertainty of clinical translation radiation safety dosage. Synchrotron X-ray imaging has the capacity to examine the microstructure and functional changes of the lung, and it is predicted to become a valuable imaging tool for early-stage lung cancer detection.

3.3. Breast Mammography

In 2021, there were 9.23 million new cases of cancer in women globally, accounting for 48% of the total new cases in the world. Breast cancer accounted for 2.26 million new cases, much outnumbering other types of cancer [

36]. Early detection and treatment of breast cancer have been shown in numerous clinical trials to significantly improve patient survival. The standard screening method for breast cancer is X-ray mammography, but its effectiveness is limited by the overlapping effect of two-dimensional projection images, which can mask tumor features and result in misdiagnosis. Moreover, conventional X-ray mammography has low sensitivity for dense breast tissue and requires compression during examination. Breast cancer imaging was among the initial medical applications of synchrotron X-rays. In 2006-2009, the first clinical studies of phase-contrast mammography were performed at the beamline of the Synchrotron Radiation for Medical Physics (SYRMEP) of Elettra in Italy [

43]. T This study included 71 patients who had breast abnormalities that remained undiagnosed after routine X-ray and ultrasound examinations at a hospital radiology department. This study included 71 patients who had breast abnormalities that remained undiagnosed after routine X-ray and ultrasound examinations at a hospital radiology department. Fig. 5A and 5B present histograms comparing the scores of standard X-ray examination and synchrotron X-ray examination. A score of 7 or higher indicates that the auxiliary diagnostic results obtained through synchrotron X-ray imaging are superior to those of the standard X-ray examination. In general, synchrotron X-ray contrast imaging substantially enhanced the visibility of breast abnormalities and glandular structures while reducing the occurrence of false positives. Three-dimensional X-ray CT imaging necessitates a relatively high radiation dosage, making it crucial to establish a safe radiation dose for clinical purposes. In 2018, Serena et al. developed a propagation-based phase-contrast computational tomography technique (PB-CT) at the imaging and medical beamline (IMBL) of the Australian Synchrotron, with which the imaging of breast cancer tissue ex vivo was realized [

44].

Figure 5C shows the comparison of digital breast tomosynthesis image and PB-CT from a mastectomy sample of a 60-year-old patient. Under the same radiation dose of imaging to that of the standard X-ray examination and tomography, the three-dimensional rendering of PB-CT could realize the global analysis of tumors, and better characterize the parameters of tumor shape, boundary, and heterogeneity. The diagnostic accuracy based on PB-CT is much higher than that of conventional X-ray CT at the same radiation dose. The feature of these imaging results can be analyzed and extracted, providing a variety of precise parameters for the assessment of clinical tumor characteristics. These parameters are the reliable basis for the accurate diagnosis of multiple lesions in preoperative protocols and even the assessment of changes during chemotherapy. Furthermore, breast cancer images obtained by synchrotron X-ray have the potential to be the gold standard for imaging diagnosis. Clinical X-ray diagnostic instruments can also benefit from medical images with improved resolution and contrast produced by synchrotron X-ray.

3.4. Bone Microtomography

Bone possesses a complex hierarchical structure. Gaining a deeper understanding of the correlation between bone structure and mechanical properties holds great potential to aid clinicians in assessing the vulnerability of patients prone to fractures, as well as initiating preventive treatment. Synchrotron X-ray technology lays the foundation for achieving enhanced temporal and spatial resolution in bone imaging. At present, various micro-CT techniques based on synchrotron X-ray have been developed, which can provide information about bone microstructure, ultrastructure, mineralization, and chemical composition. Synchrotron X-ray micro-CT enables the assessment of bone mineralization and microstructure in three-dimensional trabecular or cortical bone on a 5-10 µm scale. On a more microscopic scale of 0.5-1.5 µm, the relevant bone ultrastructure can be further observed [

45,

46]. In addition, spectroscopic techniques based on synchrotron X-ray are ideal for studying changes in bone composition under physiological or pathological conditions [

47]. X-ray phase-contrast imaging can produce higher contrast for soft tissue than attenuation-based conventional X-ray radiology, of which one is Diffraction-enhanced imaging (DEI).

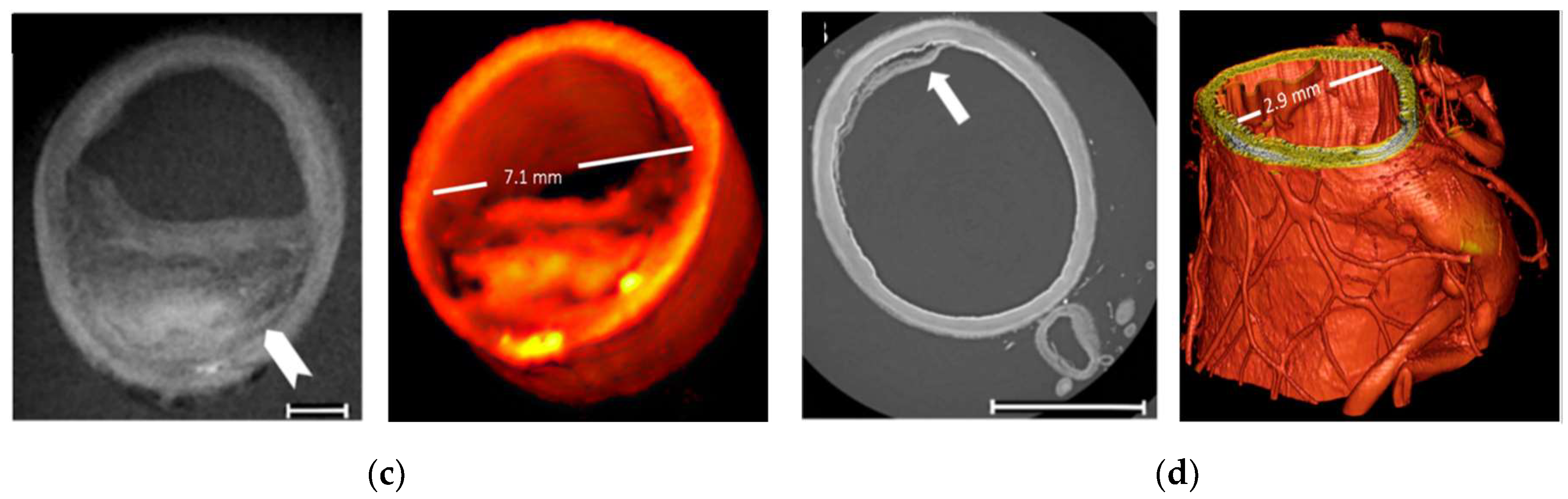

Figure 6B shows the DEI images of a human femoral head specimen obtained at the SYRMEP beamline of the Elettra light source [

48]. The images can directly distinguish vertical stripes of cartilage tissue. In the refraction image (Fig.6B, right), structures of subchondral bone, trabecular bone, and cartilage are simultaneously visible. With relatively low radiation dosages and better image quality than traditional diagnostic techniques, DEI technology can be used to image human cartilage and joints, which is predicted to be applied to the early identification of arthritis and cartilage defects brought on by degenerative diseases [

49]. The combination of synchrotron X-ray bone imaging and detection technology can achieve multi-level analysis of bone characteristics and provide a new perspective for bone research. Due to the high radiation dose, the method cannot be applied directly in vivo, but will allow researchers to conduct the study of bone quality ex vivo, including microstructure, fracture mechanisms, and mineralization. It aids physicians in developing novel methods of diagnosis, identifying new treatment objectives, and enhancing the results of treatments. The care and quality of life of patients with skeletal illnesses are subsequently improved.

4. Synchrotron X-Ray Therapy

4.1. Microbeam Radiotherapy

The The goal of radiation therapy is to selectively deliver high doses of radiation to local tumors while minimizing the damage to normal tissues. In clinical practice, how to improve effectively the radiation efficiency at tumor regions is an urgent task. Microbeam radiotherapy (MRT) in synchrotron radiation is a new tumor treatment protocol, in which high-intensity synchrotron X-ray beams are generated and the spatial division of beams is realized with multi-slit collimators (the typical width of a single microbeam is tens of microns, and the spacing is hundreds of microns), thereby creating a narrow beam plane with a high radiation dose to ablate the target tumor (Fig.7A). At present, the mechanism of MRT treatment remains to be further elucidated, which may involve the destruction of tumor blood vessels [

50], inflammation [

51], and activation of anti-tumor immune response [

52]. As the tissue positioned in the beam plane between the microbeams can tolerate an increase in radiation dosage, many preclinical types of research have shown that MRT can reduce significantly normal tissue damage while improving the efficiency of tumor radiation therapy [

53,

54].

In recent years, researchers have verified the feasibility of MRT from preclinical experiments in different animal models. Marine et al. applied MRT for the treatment of melanoma. MRT treatment exhibits a greater tumor vascular destruction impact when compared to traditional radiation therapy and can facilitate the infiltration of immune cells in the tumor site, which results in a better effect of tumor ablation and growth inhibition [

52]. Eling et al. treated rats with glioma (9LGS) in conventional wide-beam therapy and MRT in the ERSF-ID17 beamline, and found a nonlinear relationship between the tumor suppression effect and the number of MRT beam trajectories [

55]. At the same dose, MRT showed advantages in inhibiting the growth of intracranial tumors and improved the median survival time of tumor-bearing rats. In addition, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is an important reason for the inefficient delivery of most chemotherapeutic drugs to intracranial tumors [

56]. MRT could increase vascular permeability of BBB to enhance drug enrichment in the tumor site. Audrey et al. used magnetic resonance imaging to compare the BBB changes caused by conventional radiation therapy and MRT [

57]. They demonstrated that the increase in tumor vascular permeability caused by MRT was more significant than that did by conventional therapy. This was shown in earlier and longer-lasting therapeutic responses, as well as increased cell proliferation in the tumor site.

The study of MRT in animal models has become more and more mature. The application of fundamental science to the clinical setting should improve the dosage regimen to ensure safety and effectiveness. For example, at the IMBL beamline in Australia synchrotron and ID17 beamline in ESRF, scientists constructed customized experimental systems for preclinical MRT researches [

58]. Both platforms met the animal research requirements, which ranged from mice to small pigs (< 20 kg). To ensure therapy efficacy and safety, MRT development for clinical settings necessitates routine pre-treatment dosimetry assurance. T The radiation dose must be maximized in the central area of the planar beam, while the energy deposition is minimized in the area between the beams (Fig. 7B). the peak-to-valley dose ratio (PVDR) is one of the key factors. The difference between the peak and valley doses can vary by thousands of Grays over a micrometer distance, and the dose distribution within the region is also affected by the incident X-ray energy and spectrum. There is currently no consensus on the ideal X-ray energy for clinical MRT. However, depending on the application and radiation geometry, the predicted energy range is between 90-300 keV [

59,

60]. Lloyd et al. [

61] proposed a method that combines Monte Carlo simulation and a convolution-based method to simulate and calculate the MRT dose, allowing clinicians to understand the possible dose distribution of MRT and decide on the optimal dose for phase I clinical trials. Accurate and personalized treatment is a future development goal of the MRT. Elette et al. [

62] combined dosimetry, Monte Carlo simulation, and image guidance to conduct precise MRT in vitro and in vivo, and verified the tumor suppression effect and normal tissue recovery after MRT by using histological staining. Accurate measurement and characterization of the microbeam dose distribution are critical to the efficacy of MRT. Several dosimetry detection techniques have been developed, including Gafchromic films, MOSFET detectors, and silicon detectors [63-65]. In addition, conventional X-ray imaging is also impacted by motion artifacts from breathing and heartbeat. The high dose rate of synchrotron radiation beams speeds up imaging significantly, eliminates motion artifacts, and makes X-ray image-guided radiation therapy a possibility. Microbeam diffusion can result in placement mistakes since the tissue moves synchronously with the heart, yet extremely rapid dose delivery assures that the tumor site receives radiation at the micron level. The optimization of dosimetry, imaging guidance, and treatment strategy is required to enable MRT in clinical tumor therapy. More preclinical researches in medical stations are imperative for promoting MRT into the clinic..

Figure 7.

(A) Schematic of microbeam irradiation and (B) typical microbeam profile.

Figure 7.

(A) Schematic of microbeam irradiation and (B) typical microbeam profile.

4.2. Stereotactic Radiotherapy

Synchrotron stereotactic radiotherapy (SSRT) is based on local drug absorption of high heavy-element content in the tumor followed by stereotactic irradiation with low or medium-energy X-rays to enhance radiation dose deposition within the tumor only [

66]. Since June 2012, ESRF and the University Hospital of Grenoble (France) carried out the first clinical application study on contrast-enhanced SSRT and evaluated its feasibility and safety. The treatment protocol adopted by ESRF is based on stereotactic radiation, using a high-flux, quasi-parallel X-ray beam (80 keV) to irradiate tumors with high uptake of iodinated agents. The X-ray irradiates the heavy atoms accumulated in the tumor area. Then, the local energy deposition is boosted as a result of the increase in photoelectric cross-section effect, demonstrating a differential irradiation impact between tumor and normal tissue. This allowed for the successful treatment of deeper cancers while maintaining safety [

67,

68]. SSRT is a technique to deliver high-dose radiotherapy accurately to a small-volume target in a single or a small number of treatment courses, which is mainly used to treat small and well-defined tumors or high-risk areas after dissection, and requires a high-accuracy positioning device. High-dose radiotherapy can be easily achieved by using synchrotron X-ray. Compared with conventional radiotherapy, it realizes the local control of high radiotherapy radiation dose and has less radiation damage to surrounding normal tissues. In addition, the effect of SSRT can be enhanced by introducing heavy elements such as iodine and platinum. In a mouse brain tumor model, researchers increased the median survival time of tumor-bearing mice by injecting iodine, platinum, or platinized chemotherapy drugs to enhance the therapeutic effect of SSRT [

69]. At present, the follow-up time of most SSRT is short, the number of randomized trials is few comparing SSRT with other treatment options, and its efficacy needs to be further evaluated. Both SSRT and MRT are novel methods for the treatment of brain tumors and other deep-seated tumors using synchrotron radiation. Although these technologies are different in principle, both provide new means for radiotherapy, and their systematic combination is expected to achieve complementary advantages in the future.

5. Conclusions

This Biomedical applications constitute a significant component of synchrotron radiation facilities. Currently, numerous highly active synchrotron radiation light sources have established medical beamlines and conducted a series of pre-clinical and clinical medical applications. The growing need for innovative imaging technologies in cardiovascular and breast diseases has led to the use of synchrotron X-ray medical imaging in clinical trials. Based on available clinical data, synchrotron radiation experimental stations with lower radiation dosage exhibit superior image quality compared to conventional X-ray equipment presently used. Synchrotron X-ray offers excellent monochromaticity and energy tunability, effectively addressing issues such as beam hardening and contrast-agent overdose. High-quality images significantly reduce the false positive diagnosis rate for early-stage and complex tumors, serving as the gold standard for clinical diagnosis as well as the development of new medical equipment.

In preclinical studies, taking lung function imaging and bone microscopic imaging as examples, researchers have proposed high-resolution imaging schemes for different lung diseases in animal models. Synchrotron X-ray imaging can be used to visualize the structural and functional changes of lungs and bones in three dimensions, providing a new perspective to achieve multi-scale and multi-dimensional analysis of diseases. Due to the small number of available synchrotron X-ray beamlines required by high-resolution imaging, more experimental studies are still needed to support the optimization of medical imaging protocols. With the continuous improvement in simulation calculation, detection technology, and optimization scheme of radiation dose in model research, it is expected to promote the application to clinical radiology. The progress of basic image analysis technology with synchrotron X-ray will help quicken the development of new disease-diagnosis methods, determine new treatment targets, and timely evaluate the results of intervention treatment. In addition, the image data can be filtered, denoised, and artifacts removed by fast-moving machine learning methods, which can further improve the quality of the image. A massive amount of data will be created as the synchrotron radiation medical application expands in the future. Machine learning-based image processing approaches can also help with the quick identification, segmentation, and extraction of anatomical structures and pathological features.

In the field of radiotherapy, increasing the radiation dose at the tumor site while reducing or avoiding radiation damage in normal tissues has always been the ultimate goal. The development of new radiotherapy technologies such as synchrotron radiation microbeam therapy, stereotactic radiotherapy, and photon activation therapy provides another possibility for precise-targeted ablation of tumors in vivo. From animal experiments to clinical trials, the combination of high-quality diagnostic images and radiotherapy is the main direction of future development. In addition, the medical application of synchrotron radiation sources requires the participation of interdisciplinary teams from fields including biology, physics, and medicine, to offer and optimize medical end-stations as a dependable platform for multidisciplinary innovation. Currently, the progress of related fields is hindered by the complexity and limited availability of synchrotron radiation facilities, as well as the high operational and maintenance costs associated with them. Consequently, future efforts should focus on integrating and miniaturizing synchrotron radiation sources. Additionally, more beamlines dedicated to medical applications should be constructed to expedite method innovation and facilitate the clinical translation of cancer diagnosis and treatment

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.X and D.S; methodology, J.Z., M.X; resources, C.X. J.Z., M.X., Y.L., and D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.X. J.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.X., Y.L.; supervision, M.X., Y.L. and D.S.; project administration, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Suortti, P.; Thomlinson, W. Medical applications of synchrotron radiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2003, 48, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, P.; Benabderrahmane, C.; Berkvens, P.; Biasci, J.C.; Borowiec, P.; Bouteille, J.F.; Brochard, T.; Brookes, N.B.; Carmignani, N.; Carver, L.R.; et al. The Extremely Brilliant Source storage ring of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Communications physics 2023, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S. New era of synchrotron radiation: fourth-generation storage ring. AAPPS Bulletin 2021, 31, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, L.; Bouchet, A.; Nemoz, C.; Djonov, V.; Balosso, J.; Laissue, J.; Bräuer-Krisch, E.; Adam, J.F.; Serduc, R. Ultra high dose rate Synchrotron Microbeam Radiation Therapy. Preclinical evidence in view of a clinical transfer. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 139, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Bravin, A.; Mittone, A.; Eckhardt, A.; Barbone, G.E.; Sancey, L.; Dinkel, J.; Bartzsch, S.; Ricke, J.; Alunni-Fabbroni, M.; et al. A Multi-Scale and Multi-Technique Approach for the Characterization of the Effects of Spatially Fractionated X-ray Radiation Therapies in a Preclinical Model. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Brun, E.; Coan, P.; Huang, Z.; Sztrókay, A.; Diemoz, P.C.; Liebhardt, S.; Mittone, A.; Gasilov, S.; Miao, J.; et al. High-resolution, low-dose phase contrast X-ray tomography for 3D diagnosis of human breast cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 18290–18294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horng, A.; Stroebel, J.; Geith, T.; Milz, S.; Pacureanu, A.; Yang, Y.; Cloetens, P.; Lovric, G.; Mittone, A.; Bravin, A.; et al. Multiscale X-ray phase contrast imaging of human cartilage for investigating osteoarthritis formation. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, S.; Porra, L.; Suortti, P.; Thomlinson, W. Functional lung imaging with synchrotron radiation: Methods and preclinical applications. Physica Medica: European Journal of Medical Physics 2020, 79, 22-35. [CrossRef]

- Jaekel, F.; Bräuer-Krisch, E.; Bartzsch, S.; Laissue, J.; Blattmann, H.; Scholz, M.; Soloviova, J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Schültke, E. Microbeam Irradiation as a Simultaneously Integrated Boost in a Conventional Whole-Brain Radiotherapy Protocol. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappetti, V.; Potez, M.; Fernandez-Palomo, C.; Volarevic, V.; Shintani, N.; Pellicioli, P.; Ernst, A.; Haberthür, D.; Fazzari, J.M.; Krisch, M.; et al. Microbeam Radiation Therapy Controls Local Growth of Radioresistant Melanoma and Treats Out-of-Field Locoregional Metastasis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2022, 114, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrie, R.P.; Morgan, K.S.; Maksimenko, A.; Fouras, A.; Paganin, D.M.; Hall, C.; Siu, K.K.; Parsons, D.W.; Donnelley, M. Live small-animal X-ray lung velocimetry and lung micro-tomography at the Australian Synchrotron Imaging and Medical Beamline. J Synchrotron Radiat 2015, 22, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, S.; Perilli, E. Time-elapsed synchrotron-light microstructural imaging of femoral neck fracture. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2018, 84, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arhatari, B.; Nesterets, Y.; Taba, S.; Maksimenko, A.; Hall, C.; Stevenson, A.; Häsermann, D.; Lewis, S.; Dimmock, M.; Thompson, D.; et al. X-ray phase-contrast computed tomography for full breast mastectomy imaging at the Australian Synchrotron; SPIE: 2021; Volume 11840.

- Engels, E.; Li, N.; Davis, J.; Paino, J.; Cameron, M.; Dipuglia, A.; Vogel, S.; Valceski, M.; Khochaiche, A.; O'Keefe, A.; et al. Toward personalized synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.J.; Paino, J.; Day, L.R.; Butler, D.; Hausermann, D.; Pelliccia, D.; Crosbie, J.C. SyncMRT: a solution to image-guided synchrotron radiotherapy for quality assurance and pre-clinical trials. J Synchrotron Radiat 2022, 29, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, J.S.; Zhu, N.; Gasilov, S.; Ladak, H.M.; Agrawal, S.K.; Stankovic, K.M. Visualizing the 3D cytoarchitecture of the human cochlea in an intact temporal bone using synchrotron radiation phase contrast imaging. Biomed Opt Express 2018, 9, 3757–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Schart-Moren, N.; Rajan, G.; Shaw, J.; Rohani, S.A.; Atturo, F.; Ladak, H.M.; Rask-Andersen, H.; Agrawal, S. Vestibular Organ and Cochlear Implantation–A Synchrotron and Micro-CT Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahifar, A.; Swanston, T.M.; Jake Pushie, M.; Belev, G.; Chapman, D.; Weber, L.; Cooper, D.M. Three-dimensional labeling of newly formed bone using synchrotron radiation barium K-edge subtraction imaging. Physics in medicine and biology 2016, 61, 5077–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, D.; Turyanskaya, A.; Rauwolf, M.; Panahifar, A.; Cooper, D.; Wohl, G.R.; Streli, C.; Wobrauschek, P.; Pejović-Milić, A. Determining elemental strontium distribution in rat bones treated with strontium ranelate and strontium citrate using 2D micro-XRF and 3D dual energy K-edge subtraction synchrotron imaging. X-Ray Spectrom. 2020, 49, 424-433. [CrossRef]

- Andronowski, J.M.; Cole, M.E.; Davis, R.A.; Tubo, G.R.; Taylor, J.T.; Cooper, D.M.L. A multimodal 3D imaging approach of pore networks in the human femur to assess age-associated vascular expansion and Lacuno-Canalicular reduction. The Anatomical Record 2023, 306, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, P.; Di Trapani, V.; Arfelli, F.; Brombal, L.; Donato, S.; Golosio, B.; Longo, R.; Mettivier, G.; Rigon, L.; Taibi, A.; et al. Experimental optimization of the energy for breast-CT with synchrotron radiation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, P.; Mayo, S.; McCormack, M.; Pacilè, S.; Tromba, G.; Dullin, C.; Zanconati, F.; Arfelli, F.; Dreossi, D.; Fox, J.; et al. High-Resolution X-Ray Phase-Contrast 3-D Imaging of Breast Tissue Specimens as a Possible Adjunct to Histopathology. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 2642–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schültke, E.; Fiedler, S.; Menk, R.H.; Jaekel, F.; Dreossi, D.; Casarin, K.; Tromba, G.; Bartzsch, S.; Kriesen, S.; Hildebrandt, G. Perspectives for microbeam irradiation at the SYRMEP beamline. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 2021, 28, 410–418. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, Y.; Kawaai, K.; Hatano, N.; Wu, Y.; Takano, H.; Momose, A.; Ishimoto, T.; Nakano, T.; Roschger, P.; Blouin, S.; et al. Hypermineralization of Hearing-Related Bones by a Specific Osteoblast Subtype. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 1535–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, R.; Saiga, R.; Yamamoto, Y.; Uesugi, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Uesugi, K.; Terada, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; De Andrade, V.; De Carlo, F.; et al. Structural diverseness of neurons between brain areas and between cases. Translational Psychiatry 2021, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxley, S.; Sampathkumar, V.; De Andrade, V.; Trinkle, S.; Sorokina, A.; Norwood, K.; La Riviere, P.; Kasthuri, N. Multi-modal imaging of a single mouse brain over five orders of magnitude of resolution. Neuroimage 2021, 238, 118250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Ni, K.; Culbert, A.; Lan, G.; Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Kaufmann, M.; Lin, W. Nanoscale Metal–Organic Frameworks Stabilize Bacteriochlorins for Type I and Type II Photodynamic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 7334–7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamal, M.; Althobaiti, M.; Alomari, A.-H.; Dipty, S.T.; Suha, K.T.; Al-Hashim, M. Synchrotron X-ray Radiation (SXR) in Medical Imaging: Current Status and Future Prospects. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saam, T.; Herzen, J.; Hetterich, H.; Fill, S.; Willner, M.; Stockmar, M.; Achterhold, K.; Zanette, I.; Weitkamp, T.; Schüller, U.; et al. Translation of atherosclerotic plaque phase-contrast CT imaging from synchrotron radiation to a conventional lab-based X-ray source. PLoS One 2013, 8, e73513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, P.; Mu, Z.; Lin, X.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, Z.; Luo, L.; Xu, Z.; Geng, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Dynamic Detection of Thrombolysis in Embolic Stroke Rats by Synchrotron Radiation Angiography. Translational stroke research 2019, 10, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, S.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, L.; Luo, Z.; Lu, H.; Hu, J.; Wu, T. Synchrotron Radiation Imaging Reveals the Role of Estrogen in Promoting Angiogenesis After Acute Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. 2018, 43, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomlinson, W.; Gmur, N.; Chapman, D.; Garrett, R.; Lazarz, N.; Morrison, J.; Reiser, P.; Padmanabhan, V.; Ong, L.; Green, S. Venous synchrotron coronary angiography. Lancet 1991, 337, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, W.R. Intravenous coronary angiography with synchrotron radiation. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1995, 63, 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS 2020, 77, 1745-1770. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, R.; Zhao, X.; Jian, J.; Hu, D.; Qin, L.; Lv, W.; Hu, C. Phase-contrast computed tomography: A correlation study between portal pressure and three dimensional microvasculature of ex vivo liver samples from carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Microvasc. Res. 2019, 125, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, V.; Neshat, S.Y.; Rakoski, A.; Pitingolo, J.; Doloff, J.C. Drug delivery strategies in maximizing anti-angiogenesis and anti-tumor immunity. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2021, 179, 113920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 7-33.

- Bayat, S.; Fardin, L.; Cercos-Pita, J.L.; Perchiazzi, G.; Bravin, A. Imaging Regional Lung Structure and Function in Small Animals Using Synchrotron Radiation Phase-Contrast and K-Edge Subtraction Computed Tomography. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, S.R.; Salome, C.M.; Verbanck, S.; Thompson, B.; Berend, N.; King, G.G. Ventilation heterogeneity is a major determinant of airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma, independent of airway inflammation. Thorax 2007, 62, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, S.; Porra, L.; Suortti, P.; Thomlinson, W. Functional lung imaging with synchrotron radiation: Methods and preclinical applications. Phys. Med. 2020, 79, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.L.; Tafforeau, P.; Wagner, W.L.; Jafree, D.J.; Bellier, A.; Werlein, C.; Kühnel, M.P.; Boller, E.; Walker-Samuel, S.; Robertus, J.L.; et al. Imaging intact human organs with local resolution of cellular structures using hierarchical phase-contrast tomography. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, S.; Strengell, S.; Porra, L.; Janosi, T.Z.; Petak, F.; Suhonen, H.; Suortti, P.; Hantos, Z.; Sovijarvi, A.R.; Habre, W. Methacholine and ovalbumin challenges assessed by forced oscillations and synchrotron lung imaging. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 180, 296–303. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, R.; Tonutti, M.; Rigon, L.; Arfelli, F.; Dreossi, D.; Quai, E.; Zanconati, F.; Castelli, E.; Tromba, G.; Cova, M.A. Clinical study in phase-contrast mammography: image-quality analysis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, physical and engineering sciences 2014, 372, 20130025.

- Pacilè, S.; Baran, P.; Dullin, C.; Dimmock, M.; Lockie, D.; Missbach-Guntner, J.; Quiney, H.; McCormack, M.; Mayo, S.; Thompson, D. Advantages of breast cancer visualization and characterization using synchrotron radiation phase-contrast tomography. Journal of synchrotron radiation 2018, 25, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Obata, Y.; Bale, H.A.; Barnard, H.S.; Parkinson, D.Y.; Alliston, T.; Acevedo, C. Quantitative and qualitative bone imaging: A review of synchrotron radiation microtomography analysis in bone research. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2020, 110, 103887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, A.; Stroebel, J.; Geith, T.; Milz, S.; Pacureanu, A.; Yang, Y.; Cloetens, P.; Lovric, G.; Mittone, A.; Bravin, A.; et al. Multiscale X-ray phase contrast imaging of human cartilage for investigating osteoarthritis formation. J. Biomed. Sci. 2021, 28, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiacomo, M.; Campi, G.; Cancedda, R.; Cedola, A. Synchrotron radiation techniques boost the research in bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2019, 89, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehleman, C.; Majumdar, S.; Sema Issever, A.; Arfelli, F.; Menk, R.-H.; Rigon, L.; Heitner, G.; Reime, B.; Metge, J.; Wagner, A.; et al. X-ray detection of structural orientation in human articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004, 12, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coan, P.; Bamberg, F.; Diemoz, P.C.; Bravin, A.; Timpert, K.; Mützel, E.; Raya, J.G.; Adam-Neumair, S.; Reiser, M.F.; Glaser, C. Characterization of osteoarthritic and normal human patella cartilage by computed tomography X-ray phase-contrast imaging: a feasibility study. Invest. Radiol. 2010, 45, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, A.; Serduc, R.; Laissue, J.A.; Djonov, V. Effects of microbeam radiation therapy on normal and tumoral blood vessels. Phys. Med. 2015, 31, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trappetti, V.; Fazzari, J.M.; Fernandez-Palomo, C.; Scheidegger, M.; Volarevic, V.; Martin, O.A.; Djonov, V.G. Microbeam Radiotherapy-A Novel Therapeutic Approach to Overcome Radioresistance and Enhance Anti-Tumour Response in Melanoma. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potez, M.; Fernandez-Palomo, C.; Bouchet, A.; Trappetti, V.; Donzelli, M.; Krisch, M.; Laissue, J.; Volarevic, V.; Djonov, V. Synchrotron Microbeam Radiation Therapy as a New Approach for the Treatment of Radioresistant Melanoma: Potential Underlying Mechanisms. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 105, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, A.; Lemasson, B.; Christen, T.; Potez, M.; Rome, C.; Coquery, N.; Le Clec'h, C.; Moisan, A.; Bräuer-Krisch, E.; Leduc, G.; et al. Synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy induces hypoxia in intracerebral gliosarcoma but not in the normal brain. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, L.M.L.; Donoghue, J.F.; Ventura, J.A.; Livingstone, J.; Bailey, T.; Day, L.R.J.; Crosbie, J.C.; Rogers, P.A.W. Comparative toxicity of synchrotron and conventional radiation therapy based on total and partial body irradiation in a murine model. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, L.; Bouchet, A.; Ocadiz, A.; Adam, J.-F.; Kershmiri, S.; Elleaume, H.; Krisch, M.; Verry, C.; Laissue, J.A.; Balosso, J.; et al. Unexpected Benefits of Multiport Synchrotron Microbeam Radiation Therapy for Brain Tumors. Cancers 2021, 13, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; Chen, L.; Götz, J. The blood-brain barrier: Physiology and strategies for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Del. Rev. 2020; 165-166, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchet, A.; Potez, M.; Coquery, N.; Rome, C.; Lemasson, B.; Bräuer-Krisch, E.; Rémy, C.; Laissue, J.; Barbier, E.L.; Djonov, V.; et al. Permeability of Brain Tumor Vessels Induced by Uniform or Spatially Microfractionated Synchrotron Radiation Therapies. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 98, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, D.; Poole, C.M.; Livingstone, J.; Stevenson, A.W.; Smyth, L.M.L.; Rogers, P.A.W.; Hausermann, D.; Crosbie, J.C. Image guidance protocol for synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy. Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 2016, 23, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, J.; Stevenson, A.W.; Häusermann, D.; Adam, J.-F. Experimental optimisation of the X-ray energy in microbeam radiation therapy. Phys. Med. 2018, 45, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, K.; Kondoh, T.; Nariyama, N.; Fujita, H.; Washio, M.; Aoki, Y. Optimization of X-ray microplanar beam radiation therapy for deep-seated tumors by a simulation study. Journal of X-ray science and technology 2014, 22, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, L.M.L.; Day, L.R.; Woodford, K.; Rogers, P.A.W.; Crosbie, J.C.; Senthi, S. Identifying optimal clinical scenarios for synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy: A treatment planning study. Phys. Med. 2019, 60, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, E.; Li, N.; Davis, J.; Paino, J.; Cameron, M.; Dipuglia, A.; Vogel, S.; Valceski, M.; Khochaiche, A.; O’Keefe, A.; et al. Toward personalized synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petasecca, M.; Cullen, A.; Fuduli, I.; Espinoza, A.; Porumb, C.; Stanton, C.; Aldosari, A.H.; Bräuer-Krisch, E.; Requardt, H.; Bravin, A.; et al. X-Tream: a novel dosimetry system for Synchrotron Microbeam Radiation Therapy. Journal of Instrumentation 2012, 7, P07022–P07022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.A.; Paino, J.R.; Dipuglia, A.; Cameron, M.; Siegele, R.; Pastuovj ; Petasecca, M.; Perevertaylo, V.; Rosenfeld, A.; Lerch, M. Characterisation and evaluation of a PNP strip detector for synchrotron microbeam radiation therapy. Biomedical Physics & Engineering Express 2018, 4, 044002.

- Archer, J.; Li, E.; Davis, J.; Cameron, M.; Rosenfeld, A.; Lerch, M. High spatial resolution scintillator dosimetry of synchrotron microbeams. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräuer-Krisch, E.; Adam, J.F.; Alagoz, E.; Bartzsch, S.; Crosbie, J.; DeWagter, C.; Dipuglia, A.; Donzelli, M.; Doran, S.; Fournier, P.; et al. Medical physics aspects of the synchrotron radiation therapies: Microbeam radiation therapy (MRT) and synchrotron stereotactic radiotherapy (SSRT). Phys. Med. 2015, 31, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edouard, M.; Broggio, D.; Prezado, Y.; Estève, F.; Elleaume, H.; Adam, J.F. Treatment plans optimization for contrast-enhanced synchrotron stereotactic radiotherapy. Med. Phys. 2010, 37, 2445–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, L.; Deman, P.; Tessier, A.; Balosso, J.; Estève, F.; Adam, J.F. Absolute perfusion measurements and associated iodinated contrast agent time course in brain metastasis: a study for contrast-enhanced radiotherapy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014, 34, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, J.F.; Biston, M.C.; Rousseau, J.; Boudou, C.; Charvet, A.M.; Balosso, J.; Estève, F.; Elleaume, H. Heavy element enhanced synchrotron stereotactic radiotherapy as a promising brain tumour treatment. Phys. Med. 2008, 24, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).