1. Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (including preeclampsia, preE) are the second most common cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, accounting for about 60,000 maternal deaths annually worldwide [

1]. PreE is characterized by hypertension (diastolic ≥90 mm Hg) and substantial proteinuria (≥300 mg in 24 h) after 20 weeks of gestation [

2]. It occurs in 5-10% of pregnancies [

3], and its incidence is on the rise in the US [

4,

5]. The pathophysiological triggers and mechanisms of preE are not well characterized [

6]. There is no reliable biomarker for early diagnosis and no definitive therapy other than delivery.

Vasoconstrictor, digitalis-like cardiotonic steroids (CTS) are a second natriuretic system. In addition to vaso-relaxant atrial natriuretic peptides [

7], CTS are key factors in blood pressure regulation. Several CTS have been identified in human plasma and urine, including cardenolides (e.g., endogenous ouabain [EO]) and bufadienolides (e.g., marinobufagenin [MBG]). Binding to the CTS receptor site on the α-subunit of the Na+/K+ ATPase (NKA) induces natriuresis [

8,

9,

10,

11]. MBG, but not EO, is a potent vasoconstrictor [

12], impairing nitroprusside-induced relaxation of umbilical arteries [

13]. In addition to transport of Na+ and K+, the NKA functions as a receptor, which is capable of transducing CTS binding into activation of intracellular protein kinases and alterations in Ca2+ levels, ultimately altering the cell surface expression of the NKA and Na+/H+ exchanger [

14]. MBG participates in EGFR-dependent cell signaling, which induces oxidative stress and promotes fibrosis [

15]. In this light, CTS can be viewed as a new class of steroid hormones, rather than simply as endogenous inhibitors of Na+ transport. Recent data support a role for CTS, specifically MBG, in the pathogenesis of hypertension and preE. Normal plasma MBG (0.225 nM) increases 7-fold in essential hypertension and congestive heart failure, and over 70-fold in chronic renal failure [

10,

11].

MBG, but not endogenous ouabain, is markedly elevated in preE [

16,

17,

18]. Puschett and co-workers developed an ELISA with high specificity for MBG [

19], which revealed a 5-fold increase in serum MBG and a 4-fold increase in urine MBG levels in preE patients vs. normotensive pregnant women. Plasma levels of MBG, but not EO, become elevated in patients with preE [

17,

18,

19]. We demonstrated that the MAPK signaling is involved in the deleterious effects of MBG on cytotrophoblast (CTB) function, which is important for normal placental development [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. High blood levels of MBG during pregnancy may directly contribute to preE pathogenesis, in part through detrimental cellular signaling in CTB cells [

25,

26]. In a rat model of the syndrome, MBG induces hypertension, proteinuria, intrauterine growth restriction, and increased weight gain, but these symptoms are prevented by an MBG antagonist [

11]. A syndrome with many phenotypic characteristics of preE results when pregnant rats are given weekly injections of desoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA), and their tap water is replaced with normal saline [

27]. This syndrome can be reproduced by daily injections of MBG beginning in early pregnancy [

27,

28]. Angiogenic imbalance plays a role in the pathogenesis of preE in this rat model; however, an earlier event appears to be the elaboration and secretion of MBG [

29]. If MBG and other CTS promote preE pathology, reversing the effects of MBG by scavenging or competition represents a reasonable treatment approach. Digibind and DigiFab are polyclonal anti-digoxin antibodies with some cross-reactivity for other CTS. Both of these polyclonals have been shown to reduce circulating levels of CTS. In animal models, Digibind reverses MBG-induced vasoconstriction by restoring the activity of erythrocyte Na/K-ATPase, a target enzyme for CTS [

30,

31]. Recently, it was shown that plasma levels of endogenous MBG are related to salt sensitivity in men [

32]. Also, magnesium can increase the efficacy of immunoneutralization of MBG-induced NKA inhibition in erythrocytes ex vivo [

33]. It was shown that DigiFab interacts with CTS from preE plasma and reverses preE-induced NKA inhibition. Despite their very limited reactivity with MBG, both Digibind and DigiFab have been explored for treatment of patients with preE [

34]. Digibind treatment lowered blood pressure and reduced proteinuria in a preE rat model [

29]. It was reported to improve or slow progression of preE in a few small clinical trials [

30,

31,

35]. RBG is a structural congener of MBG that acts as a competitive antagonist of MBG. We observed that when RBG is administered early in pregnancy, it prevented the manifestations of preE in a rat model of preE [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Conversely, when RBG is given to normally pregnant rats, they develop the preE syndrome [

37]. In a preliminary study, Vu et al. administered a polyclonal MBG antiserum (MBG-P, Ab) in a rat model of preE (PDS) on the 16th, 17th, and 18th day of pregnancy and demonstrated that the blood pressures of PDS rats returned to normal [

28]. Fedorova et al. reported similar data in which a murine monoclonal antibody to MBG (3E9) lowered blood pressure in pregnant rats rendered hypertensive by treatment with high salt diets [

41]. Due to the potential for immunogenicity of polyclonal and murine antibodies, human monoclonals are much preferred for use in pregnant patients.

We have identified a novel anti-MBG human monoclonal antibody for potential use as an innovative, effective, and safe therapeutic for preE. As the focus of this work is on developing a blockade of MBG effects in pregnancy, we plan to assay MBG in patients at high risk for preE to test the hypothesis that MBG increases prior to preE development. We and others have already shown that MBG is elevated once preE has been diagnosed [

16,

17,

18].

In addition, we have conducted a preliminary study of the efficacy of the antibody in the desoxycorticosterone (DOCA)-saline rat model of preeclampsia. The DOCA model is a volume-expansion model of preE in pregnant rats first described by Puschett and colleagues [

27,

28], in which substitution of saline for normal drinking water and injection of deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) induces volume expansion and elevated plasma and urine MBG levels, and results in a syndrome with many of the phenotypic characteristics of human preE: hypertension, proteinuria, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (reduced pup number and litter weight) [

27,

28,

42].

These data will allow us to assess the potential of anti-MBG monoclonal antibody therapy to intervene in the pathophysiological cascade of preE.

2. Materials and Methods

Anti-MBG human monoclonal antibodies: A human phagemid library with 1.2x10e10 independent clones was panned against MBG conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA). Several strategies were employed to enrich for MBG binding clones as the panning proceeded through 4 rounds of enrichment including linking multiple CTS competitive elution profiles together to increase the likelihood for high affinity MBG only binders. Approximately 660 individual clones representing 6 different pan-enriched fractions were tested for binding to MBG in ELISA, and ~110 putative binders were further analyzed by BstN1 fingerprinting, DNA sequencing, and/or MBG competitive ELISA. These reduced to ~14 unique clones, of which 7 were converted to human IgG1 for testing in cell-based MBG neutralization assays. Clones representative of distinct CTS competitive elution profiles were also characterized for their binding profile on MBG-BSA in the presence of various CTS (MBG, RBG, cinobufagin-CINO, ouabain-OUB, digoxin-DIG) either as phage, soluble Fab, or IgG. Initial studies were conducted with these phage-derived antibodies.

A second strategy was to humanize the previously described 3E9 murine mAb [

41]. Humanization was performed using a proprietary modification of the method of Queen et al. [

43]. The complementarity determining regions (CDR) of the heavy (IgG1) and light (kappa) chains of the mouse antibody were grafted onto acceptor human sequence frameworks, where the framework is defined as the segment of the variable regions excluding the CDRs. The choice of human acceptor frameworks was made by aligning the mouse framework sequences against a database (see below) of human framework sequences to find the closest human homolog for each chain (typically 65-70% sequence identity). Three potential heavy chains (H1, H2, and H3) and two potential light chains (L1 and L2) were designed. The differences among these variants reflect the possible importance of retaining some mouse framework amino acids that may be involved in binding. The proposed designs show equivalent to better similarity to human germlines (87-95%) than the set of FDA-approved human antibodies. A mix and match strategy was used, so that all six combinations of the humanized heavy and light chains were expressed in order to determine the best variant. 293F cells (Invitrogen) were cultured in serum-free medium (Freestyle, Invitrogen) in 6-well plates and co-transfected with the various combinations of heavy and light chain plasmids at a 1:1 DNA ratio. Transfections were carried out using polyethyleneimine. On day 3 post-transfection, cell culture supernatants were harvested. Antibody concentrations in the supernatants were estimated from SDS-PAGE gels. Based on developability criteria (data not shown), the humanized anti-MBG monoclonal antibody H3L2 was ultimately chosen as the lead candidate for further preclinical studies.

Cell proliferation assay: MBG (2 nM, chosen in preliminary experiments to produce 50-75% inhibition of proliferation) was pre-treated with control IgG or various anti-MBG humAbs at 20 μg/mL for 1 h prior to adding to human vascular endothelial (HUVEC) cells in 12-well plates. After 48 h, DNA synthesis was assessed by incorporation of 3H-thymidine. Briefly, cells were washed twice with 1X phosphate-buffered saline, then incubated with 3H-thymidine (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) at 37°C for 48h. After washing twice with ice-cold 10% trichloroacetic acid, cells were lysed with 0.5 mL 1N NaOH at room temperature, then neutralized with 0.5 mL 1N HCl. The mixture (0.5 mL) was counted in a scintillation counter (Beckman LS 6000SC).

Human CTB proliferation assay: The human CTB cell line Sw-71 was maintained as previously described [

22]. CTBs were treated with DMSO (vehicle) or 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 nM of MBG for 48 hours. Some cells were pretreated with anti-MBG monoclonal antibodies H3L2 for 2 hours. Culture media were collected for analysis of pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic secreted proteins. Cell viability was measured using a CellTiter Assay (Promega). Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), placental growth factor (PlGF), sFlt-1, soluble endoglin (sEng), and IL-6 were measured in culture media by ELISA. Statistical comparisons were performed using analysis of variance with Duncan’s post hoc test.

Human CTB Migration Assay: Human CTBs were treated with DMSO (vehicle) or 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 nM of MBG for 48 hours, then pretreated or not treated with anti-MBG monoclonal antibodies H3L2 for 2 hours. Migration assays were performed as previously described [

22]. Cell migration was measured using a CytoSelect Assay (Cell Biolabs) as described previously by Uddin et al. [

22,

23]. After the CyQuant GR Dye solution was added to the cells, fluorescence was measured at 480 nm / 520 nm on a fluorescence plate reader (CytoFluor Series 4000 Fluorescence Multi-Well Plate Reader, Applied Biosystems).

Human CTB Invasion Assay: Human CTBs were treated with DMSO (vehicle) or 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 nM of MBG for 48 hours. Some cells were pretreated, while others were not treated, with anti-MBG monoclonal antibodies H3L2 for 2 hours. Invasion assays were performed as previously described [

22]. Cell invasion was measured using EGF-induced invasion was determined using the quantitative FluoroBlok invasion assay as described previously by Uddin et al. [

22,

23].

Measurement of angiogenic factors: Levels of pro-angiogenic factors, VEGF and PlGF, and anti-angiogenic factors, sFlt-1 and sEng, were measured with commercially available kits (Human VEGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (DVE00); Human PlGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (DPG00); Human sVEGF R1/Flt-1 Quantikine ELISA Kit (DVR100B); Human Endoglin/CD105 Quantikine ELISA Kit (DNDG00); R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

DOCA-saline rat model of preeclampsia: Female Sprague-Dawley rats (200-250 g, Charles River) were acclimatized for 1 week, and mated with male Sprague-Dawley rats (275-300 g). Pregnancy was confirmed by the presence of vaginal plugs or by examination of vaginal smears. Each rat was housed separately.

Five groups of rats were studied (n=10 per group): Group 1 (NP): normal pregnant rats; Group 2 (PDS): pregnant rats injected i.p. initially with 12.5 mg of DOCA in a depot form, followed by a weekly i.p. injection of 6.5 mg of DOCA, and whose drinking water is replaced with 0.9% saline; Group 3 (NPM): Normal pregnant rats given daily injections of MBG (7.65 µg/kg/day) once pregnancy was established on day four of the experiment; Group 4 (PDS-3E9): rats administered DOCA and saline as for Group 2, and also given the murine anti-MBG antibody 3E9 (2.2 mg/kg/day) on GD16, GD17, and GD18; and Group 5 (PDS-H3L2): rats administered DOCA and saline as for Group 2, and also given the humanized anti-MBG antibody H3L2 (2.2 mg/kg/day) on GD16, GD17, and GD18. The doses of antibodies were determined to be sufficient to neutralize anticipated levels of plasma MBG.

Systolic blood pressure (BP) was measured by tail cuff at days 17-19. At least 3 readings were taken after BP had stabilized, and the mean of these values was calculated. The reported BP values are the mean of the daily measurements. At 18-20 days of pregnancy, 24-hour urine was collected in the absence of food to avoid contamination of the measurement of the protein amount in urine by any fallen food particles. Each rat was housed separately in a metabolic cage during this portion of the study. The 24-hour protein excretion was measured and was normalized to creatinine. The rats were sacrificed after the last measurement on GD18-20, and blood samples were taken. The number of fetal pups was counted and examined. The mean number of pups and any developmental or histological abnormalities in the pups were assessed. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test. Two-way ANOVA was conducted, and the SAS software was used. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The animal studies were conducted with the approval of the IACUC of Texas A&M Health Sciences University/Baylor Scott & White; IACUC number: 110500; IACUC approval date: 8/18/2017), in conformance to the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

3. Results

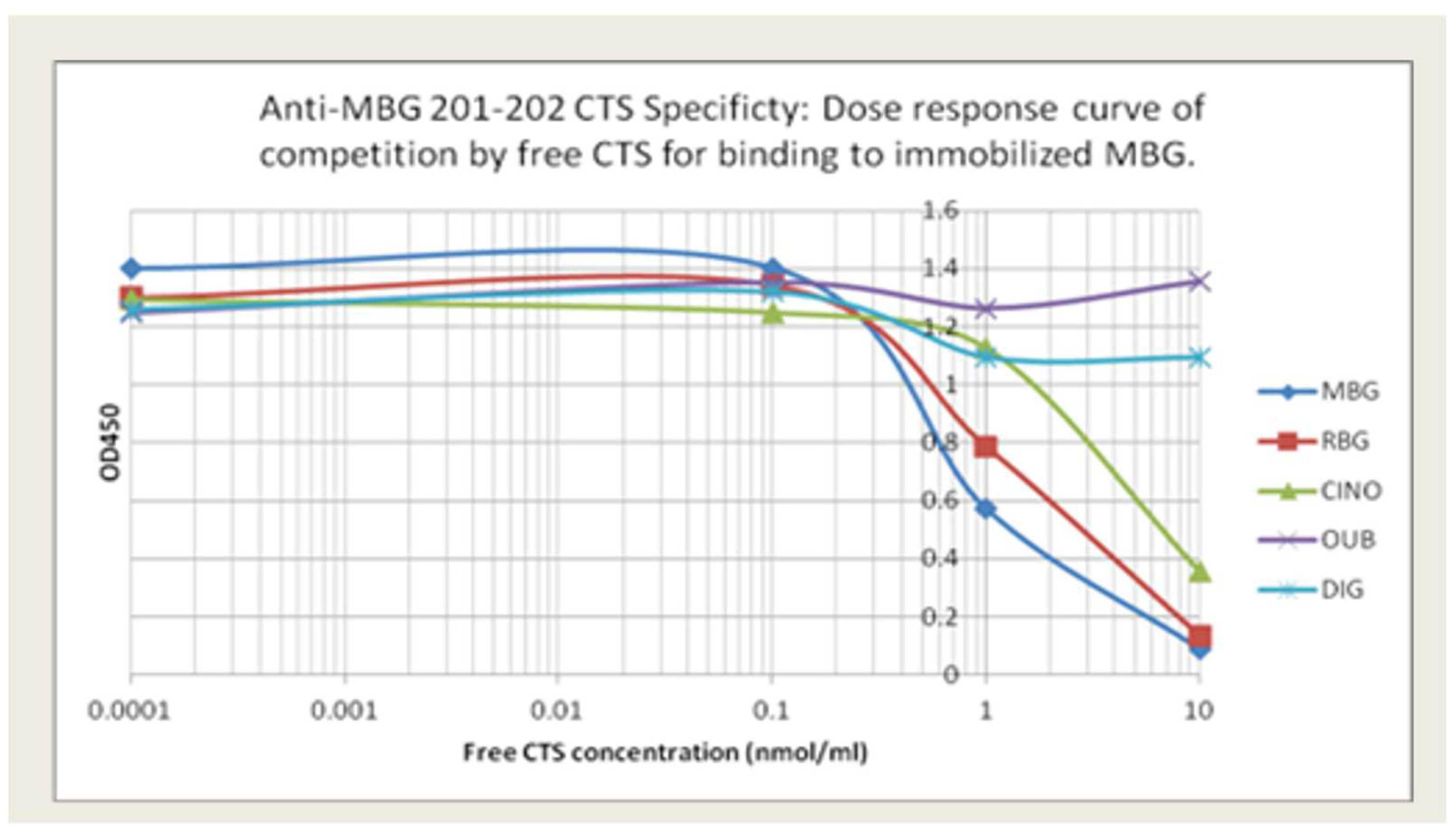

Anti-MBG antibodies: The relative specificity for MBG of our lead phage antibody, 201/202, and the two back-up mAbs, 206/208 and 236/237, is shown in

Figure 1. Binding of 201/202 to immobilized MBG is best inhibited by free MBG, with partial inhibition by RBG and CINO. In contrast, DIG and OUB did not compete for binding at all.

Table 1 summarizes the binding avidity and specificity of the lead candidate and the two alternatives. MBG was conjugated to BSA or KLH to facilitate coating of plates. All three mAbs showed low binding to BSA or KLH and minimal binding to RBG and related CTS.

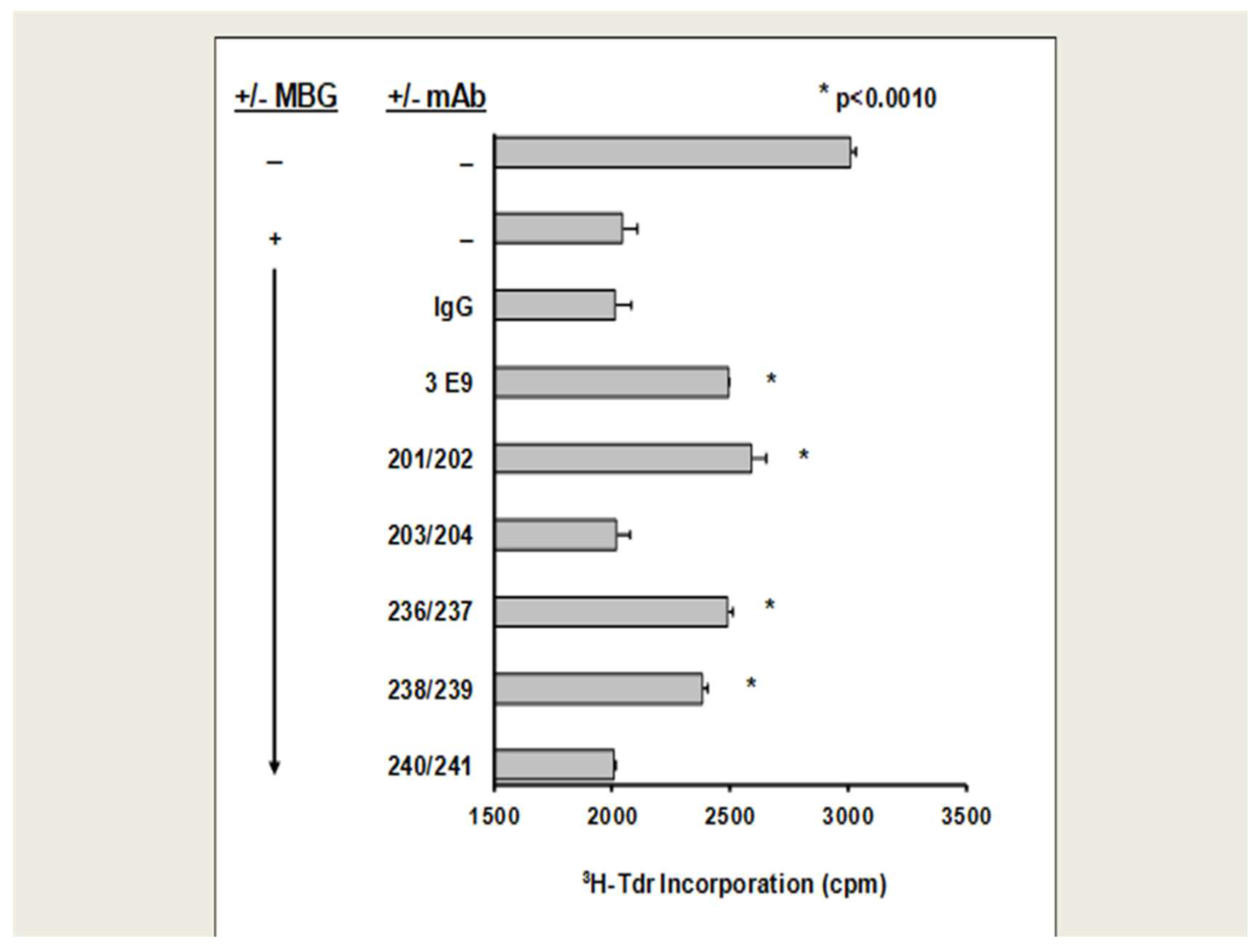

HUVEC proliferation: With the exception of humAbs 203/204 and 240/241, all anti-MBG humAbs, as well as the murine antibody 3E9, reduced MBG inhibition of cultured human umbilical cord venous endothelial cell (HUVEC) proliferation (

Figure 2).

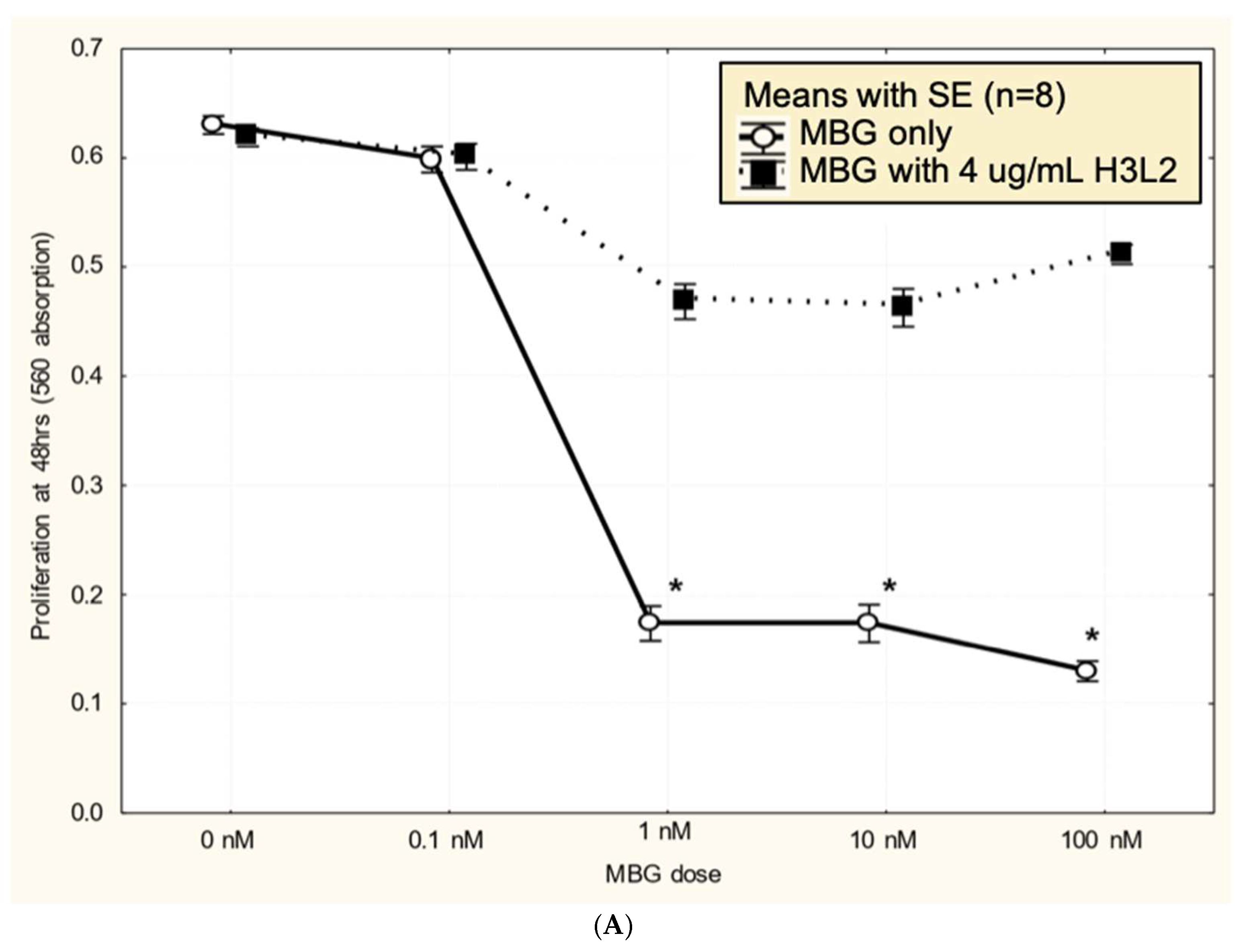

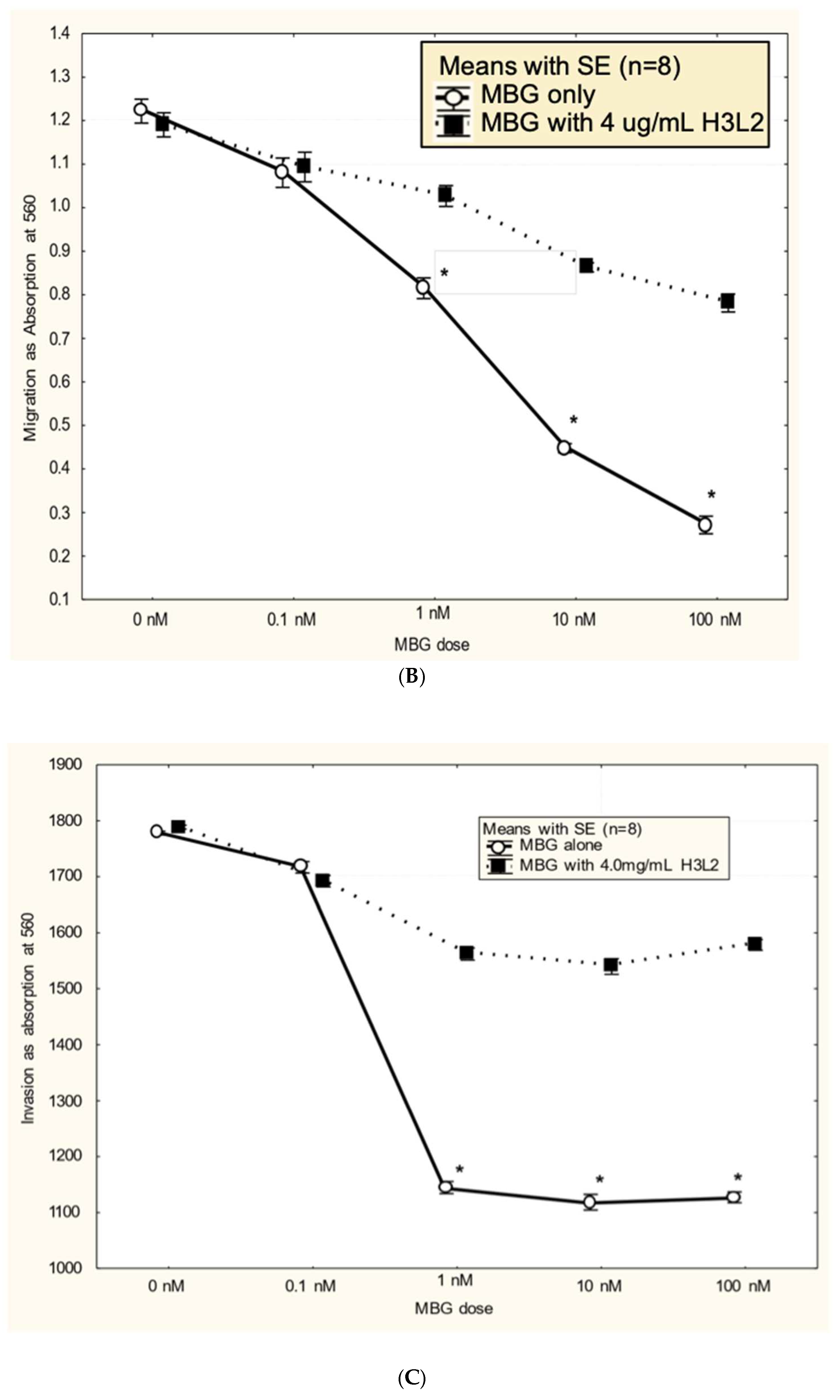

Humanized anti-MBG antibody H3L2 attenuated MBG-induced dysfunction in CTB cells: CTB cells exposed to MBG at levels of 1 nM or greater had decreased (p < 0.05) proliferation (

Figure 3A), migration (

Figure 3B), and invasion (

Figure 3C) relative to the control with no added MBG. Pretreatment with 4 ug/mL humanized anti-MBG antibody H3L2 significantly (p < 0.05) attenuated the MBG-induced downregulation of CTB cell proliferation (

Figure 3A), migration (

Figure 3B), and invasion (

Figure 3C). MBG at 1 nM provided a maximum effect, and no dose-dependence in either MBG or H3L2 was observed at > 1 nM MBG in the proliferation or invasion assays. In contrast, MBG dose-dependence was seen with the migration assay, where > 1 nM MBG attenuated invasion, and H3L2 provided significant, although incomplete, normalization of migration.

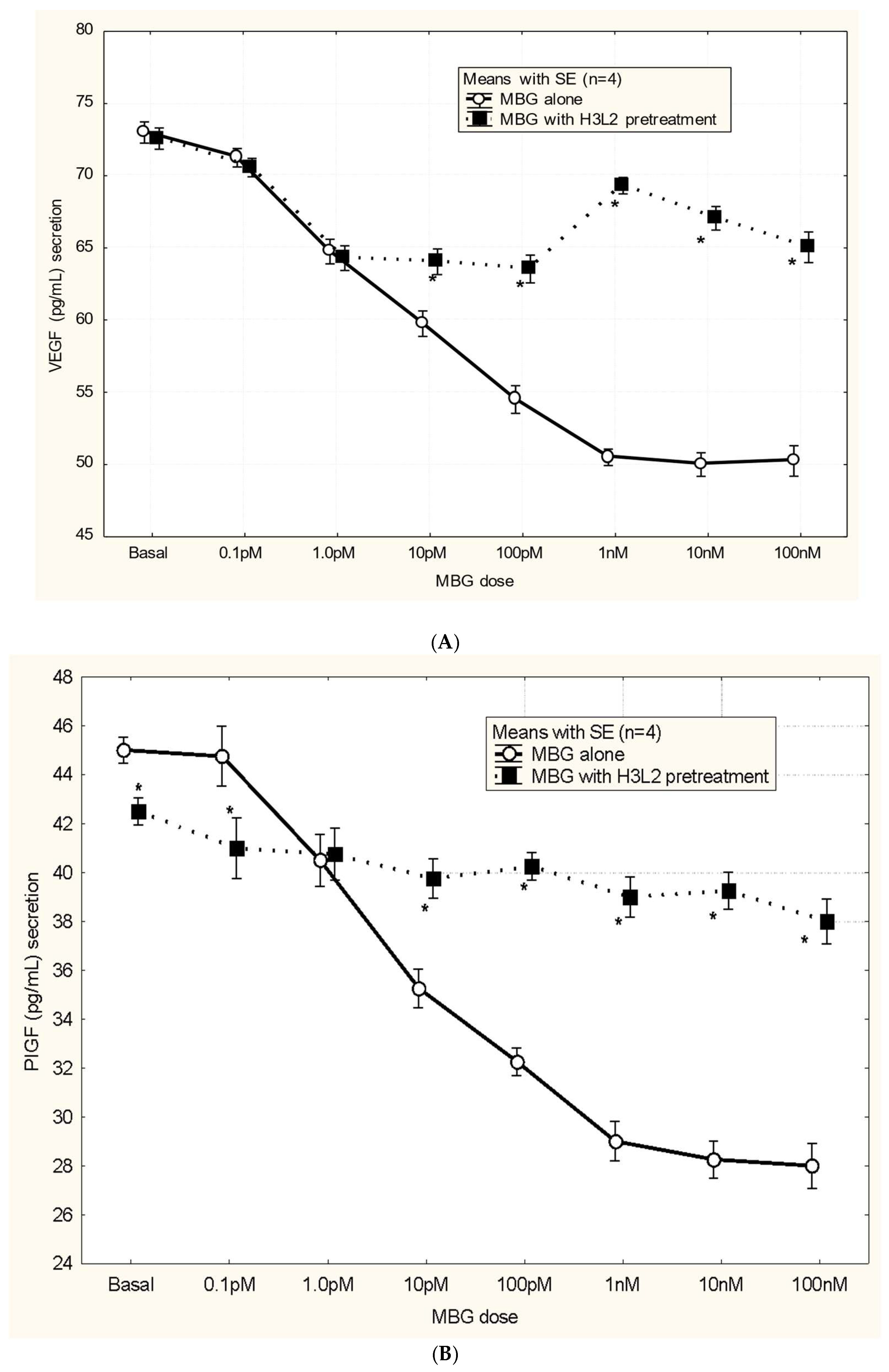

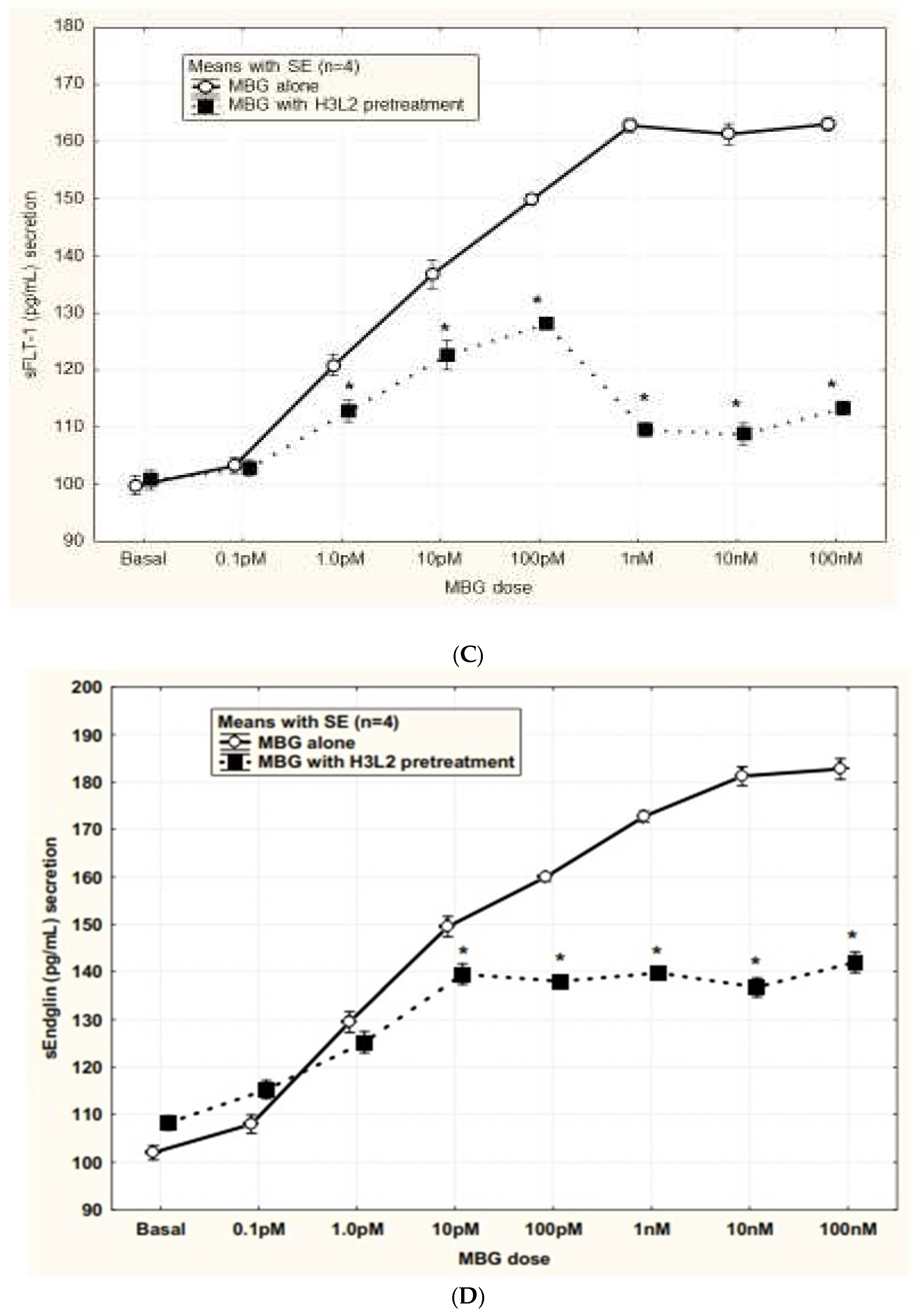

Humanized anti-MBG antibody H3L2 attenuated CTB cells from the MBG-induced anti-angiogenic milieu: MBG at levels of 1 nM or greater had decreased secretion of VEGF and PIGF (p < 0.05;

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B) and increased secretion of sFlt-1 and sENG (p < 0.05;

Figure 4C and

Figure 4D) by CTB cells. Pretreatment with H3L2 significantly (p < 0.05) attenuated the MBG-induced modulation of angiogenic VEGF and PIGF (p < 0.05;

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B) and anti-angiogenic factors (p < 0.05;

Figure 4A and

Figure 4B).

Efficacy of anti-MBG antibodies in the DOCA-saline rat model: DOCA and saline treatment resulted in increased blood pressure, proteinuria, an overall reduction in litter size, and fetal malformations in pregnant rats. The administration of MBG alone had similar effects, as previously reported (Vu, 2005). Anti-MBG murine antibody 3E9 prevented these increases in blood pressure, proteinuria, and fetal malformations. Humanized anti-MBG antibody H3L2 produced a similar effect as the parent murine antibody 3E9 (

Table 2).

Either administration of exogenous MBG or saline drinking water results in significant increases in blood pressure (BP) and urinary protein, together with a reduction in litter size and an increase in malformed pups. Anti-MBG antibody rescues the normal phenotype in pregnant rats on saline water. Blood pressure was measured by tail cuff. Urine protein was measured only at the end of the study and was normalized to creatinine. Baseline (initial) blood pressure and urine protein were not significantly different among treatment groups. Animals treated with DOCA and saline (NPS) showed statistically significant increases in blood pressure, proteinuria, number of pups, and percentage of malformed pups over control pregnant animals (NP) (p<0.05). Animals treated with MBG alone (no DOCA or saline) (NPM) showed statistically significant increases in blood pressure, proteinuria, number of pups, and percentage of malformed pups over control pregnant animals (NP) (p<0.05). Animals treated with anti-MBG murine antibody 3E9 or with anti-MBG human antibody H3L2 did not show a statistically significant increase in blood pressure or proteinuria or any decreased litter size or malformed pups relative to control DOCA-saline-treated animals (PDS). Multiple controls were included in the study. Normal pregnant rats serve as a negative control for the effect of MBG or saline treatment. MBG-treated rats and DOCA/saline-treated rats serve as a positive control for the development of preE symptoms. Animals treated with the murine antibody 3E9 serve as a positive control for the reduction in preE symptoms in the model. Based on our own previous experience and prior publications [

28], 3E9 is expected to reduce blood pressure, proteinuria, and fetal malformations.

4. Discussion

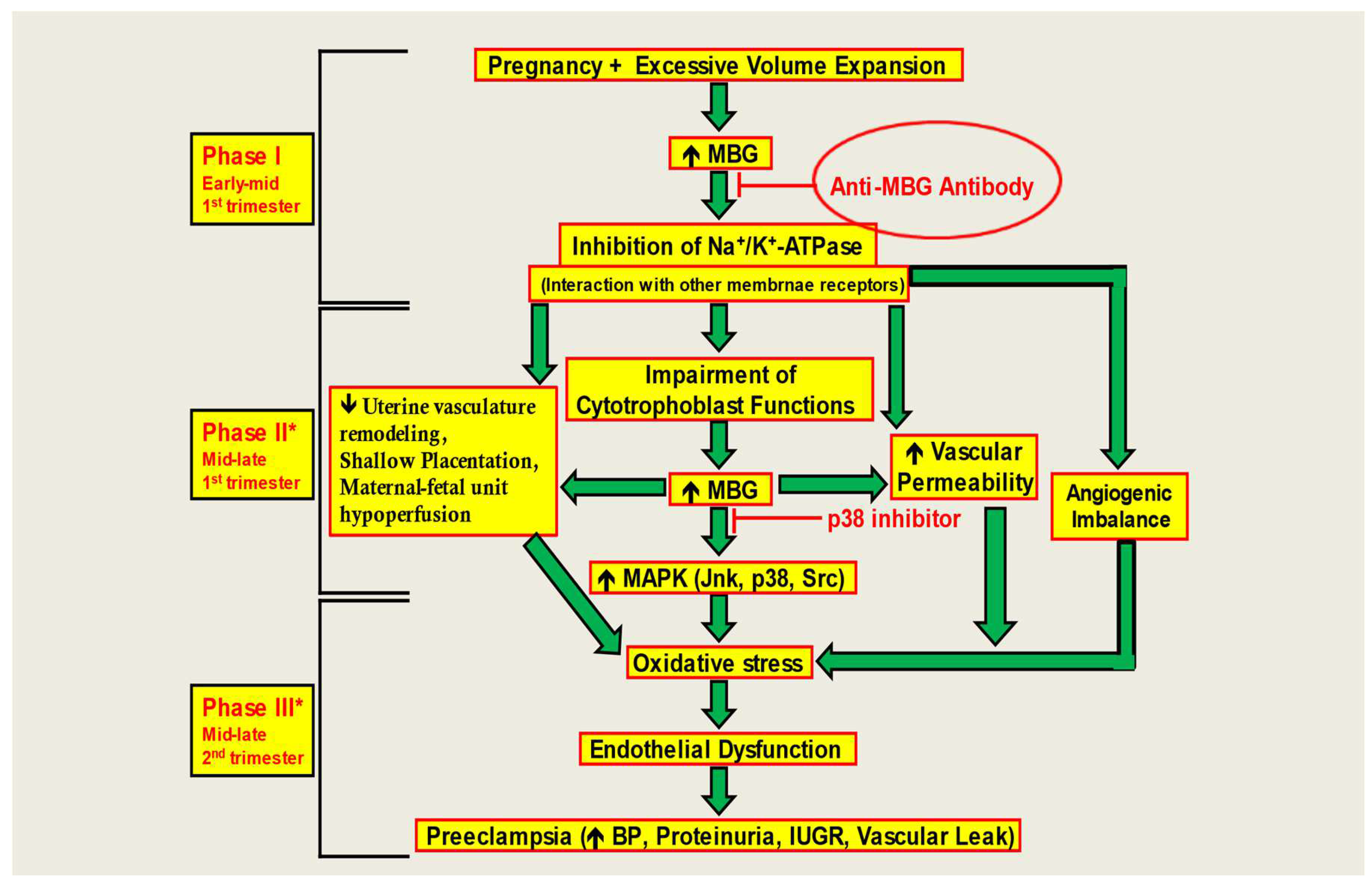

The results of our study add to several decades of literature implicating MBG as among the key factors for preE. Here, we demonstrate dysfunction in CTB cells due to an anti-angiogenic milieu produced by MBG treatment. Proper placental formation requires adequate CTB cell invasion in the endometrium. In preE, proper differentiation of CTB cells is obstructed leading to abnormal placental formation, culminating in an array of issues for the pregnancy and the fetus [

22,

23]. Due to preE, the extent of CTB cell invasion in the uterine lining is greatly affected, and consequently a reduction in uteroplacental perfusion results in placental focal ischemia and hypoxia [

22,

23]. Elevated plasma levels of MBG are seen in patients with preE [

16,

17,

18]. Uddin et al. saw that MBG increases microvascular barrier permeability in an animal model of preE [

44]. Similarly, preE patients have been shown to demonstrate increased vascular permeability [

45,

46,

47]. In addition, they determined that MBG-induced impairment of CTB cell function was a result of decreased ERK1/2 activity, and MBG treatment drastically affected the growth factor-induced migration and invasion of CTB cells [

22,

23]. MBG interferes with CTB function and may cause defective placentation, resulting in a lack of vascular remodeling. Consequently, hypoperfusion of the maternal-fetal unit is possible. MBG causes hypoxia and ischemia leading to continued elevation of MBG levels and an angiogenic imbalance. CTB dysfunction is mediated by alterations in signaling pathways that stimulate apoptotic and stress signaling. These changes culminate in the production of endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress leading to the induction of the preE syndrome [

46].

Fedorova et al. hypothesized MBG to be a potential target for immunoneutralization in preE [

48]. Immunoassay based on 4G4 anti-MBG mAb revealed a three-fold increase in renal excretion of MBG in hypertensive Dahl-S rats. Their experimental findings revealed that 3E9 anti-MBG mAb decreased blood pressure and restored vascular sodium pump activity [

48]. Uddin et al. recognized RBG as a potential compound to negate the effects of MBG-induced preE since RBG acts as a competitive antagonist congener of MBG [

49]. It is known to prevent the development of hypertension, proteinuria, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in early pregnancy [

42,

45]. MBG is known to downregulate aortic AT1 receptor expression leading to multiple downstream reactions ultimately causing CTB dysfunction. Western blot results showed that RBG treatment increased expression of AT1 receptor, thus attenuating the negative effects of MBG [

49]. Digibind, a polyclonal, anti-digoxin Fab with some cross-reactivity to MBG, reverses the preE syndrome in a rat model, alleviates inhibition of NKA by MBG, and normalizes blood pressure in preE patients [

30]. Immuno-neutralization of MBG by Digibind or treatment with RBG can attenuate the development of preE in animal models, providing hope that treatments aimed at interfering with MBG-induced pathophysiology can be effective.

Excessive volume expansion during first trimester of pregnancy elevates circulating levels of MBG which causes an increase in the expression of RAS including AT1 receptor. RAS is known to be naturally present in the endometrial region and is known to function in uteroplacental blood flow and vascular remodeling during pregnancy [

55]. Due to upregulation of RAS, oxidative stress increases, leading to endothelial dysfunction [

55]. MBG also induces fibrosis and contributes to vascular stiffening in preE. This pro-fibrotic effect has been demonstrated in renal and cardiovascular tissues [

50,

51], and more recently in preE [

13]. Recent data strongly support the involvement of MBG in preE [

18,

19]. CTS, "endogenous digoxin-like factors" (EDLF), have been known since the 1980s to increase significantly during pregnancy induced hypertension and preE [

31,

52,

53,

54].

In this study, we demonstrate that anti-MBG antibodies can reverse the anti-angiogenic milieu in CTB cells (

Figure 5). This restores the invasive capacity of CTB cells for proper placental formation. We further show that anti-MBG human monoclonal antibody H3L2 can reverse hypertension, proteinuria, and fetal effects in a rat model of preE, even when given late in pregnancy. We note that the time of administration in the DOCA-saline model corresponds to second trimester of human gestation [

56], illustrating a shortcoming of rodent models of preE. Non-human primate models are needed to facilitate translational studies of this and other therapies.

By analogy to other approved therapeutic antibodies, this antibody will likely have a plasma half-life in humans of approximately 3 weeks. Thus, we envision a single course of treatment, initially for the high-risk patient, to enable continuation of pregnancy toward a normal delivery time, with improved maternal and neonatal outcomes.

5. Conclusions/Perspectives

The data of this study suggest that anti-MBG antibody binds to MBG, neutralizing it, and preventing downstream signaling in vitro. In a rat model of preE, treatment with anti-MBG antibody was effective at normalizing blood pressure, kidney function, and fetal birth weights. These data provide a strong foundation for further preclinical development of this antibody and its eventual testing in the clinic. A digitalis-like factor, marinobufagenin (MBG) has been implicated as a causative factor in preeclampsia (preE). A human monoclonal antibody (humAb) that binds MBG with high affinity and specificity has been identified. The Anti-MBG antibody has the greatest potential for therapeutic use.

Clinical/Pathophysiological Implications

An anti-MBG monoclonal antibody for preE in a rat animal model has been evaluated. The MBG-Bind antibody is fully human and is expected to be much less immunogenic than Digibind or DigiFab. We will obtain both efficacy and safety data in vivo in normal and preE pregnant rats. As the focus of this study is on developing a therapeutic blockade of MBG in pregnancy, a study has been designed in patients at high risk for preE to test the hypothesis that MBG increases occur prior to development of signs and symptoms. The work is innovative because the study will use both in vivo and in vitro data obtained to establish whether the MBG-induced pathophysiological cascade can be blocked and whether there is a window for treatment early in human pregnancy when MBG effects might be mitigated by antibody therapies without maternal and fetal side effects.

Author Contributions

Composing and preparing the article: A.F.P., S.H.A., M.Z., and N.V.; Development and efficacy of anti-MBG antibodies: H.W., J.M.W., B.Y., and J.W.L.; Reviewing the article: D.C.Z., and T.J.K.; Planning, reviewing, and approving of the article for submission: M.N.U.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the able leadership of the late Susan C. Wright PhD during the humanization and early antibody screening at Panorama Research. Funding for this work was provided by Scott, Sherwood and Brindley Foundation and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology (MNU) and the Noble Centennial Endowment for Research in Obstetrics and Gynecology (TJK), Baylor Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, Texas. The CTB cell line Sw-71 was kindly provided by Dr. Gil G. Mor at Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA. MBG was a kind gift from Drs. Alexei Y. Bagrov, Edward G. Lakatta, and Olga V. Fedorova at the National Institute on Aging (NIA), Baltimore, Maryland.

Availability of data and material

Data will be made available upon request.

Ethics Declaration

John M. Wages, Bo Yu, and James W. Larrick are co-founders of CTS Biopharma LLC, which has an exclusive license to US Patent 8,038,997 covering anti-MBG monoclonal antibodies. CTS Biopharma seeks to commercialize the anti-MBG human monoclonal antibody described in this paper for preeclampsia and other indications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Abbreviations

MBG: marinobufagenin, CTS: cardiotonic steroids; preE: preeclampsia; DOCA: desoxycorticosterone acetate; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; RBG: resibufogenin; CINO: cinobufagin; EO: endogenous ouabain; DIG: endogenous digoxin; HUVEC: human vascular endothelial cells

References

- Dimitriadis E, Rolnik DL, Zhou W, Estrada-Gutierrez G, Koga K, Francisco RPV, Whitehead C, Hyett J, da Silva Costa F, Nicolaides K, Menkhorst E. Pre-eclampsia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023; 9:8. Erratum in: Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023; 9:35.

- von Dadelszen, P.; Magee, L.A. Pre-eclampsia: An Update. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014, 16, 1–14, . [CrossRef]

- Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010; 376:631-644.

- Berg, C.; Mackay, A.; Qin, C.; Callaghan, W. Overview of Maternal Morbidity During Hospitalization for Labor and Delivery in the United States: 1993 to 1997 and 2001 to 2005. Obstet. Anesthesia Dig. 2010, 30, 95–96, . [CrossRef]

- Wallis, A.B.; Saftlas, A.F.; Hsia, J.; Atrash, H.K. Secular Trends in the Rates of Preeclampsia, Eclampsia, and Gestational Hypertension, United States, 1987-2004. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008, 21, 521–526, . [CrossRef]

- Pridjian G, Puschett JB. Preeclampsia, Part I: Clinical and pathophysiological considerations. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002; 57:598-618,.

- Fedorova, O.V.; Agalakova, N.I.; Morrell, C.H.; Lakatta, E.G.; Bagrov, A.Y. ANP Differentially Modulates Marinobufagenin-Induced Sodium Pump Inhibition in Kidney and Aorta. Hypertension 2006, 48, 1160–1168, . [CrossRef]

- Schoner, W.; Scheiner-Bobis, G. Endogenous and exogenous cardiac glycosides: their roles in hypertension, salt metabolism, and cell growth. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2007, 293, C509–C536, . [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, O.V.; I Tapilskaya, N.; Bzhelyansky, A.M.; Frolova, E.V.; Nikitina, E.R.; A Reznik, V.; A Kashkin, V.; Bagrov, A.Y. Interaction of Digibind with endogenous cardiotonic steroids from preeclamptic placentae. J. Hypertens. 2010, 28, 361–366, . [CrossRef]

- Puschett, J.B.; Agunanne, E.; Uddin, M.N. Emerging Role of the Bufadienolides in Cardiovascular and Kidney Diseases. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 56, 359–370, . [CrossRef]

- Puschett, J.; Agunanne, E.; Uddin, M. Marinobufagenin, resibufogenin and preeclampsia. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2010, 1802, 1246–1253, . [CrossRef]

- Bagrov AY, Roukoyatkina NI, Pinaev AG, Dmitrieva RI, Fedorova OV. Effects of two endogenous NKA inhibitors, marinobufagenin and ouabain, on isolated rat aorta. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995; 274:151-158.

- Nikitina ER, Mikhailov AV, Nikandrova ES, Frolova EV, Fadeev AV, Shman VV, Shilova VY, Tapilskaya NI, Shapiro JI, Fedorova OV, Bagrov AY. In preeclampsia endogenous cardiotonic steroids induce vascular fibrosis and impair relaxation of umbilical arteries. J Hypertension. 2011; 29:769-776.

- Liu, J.; Shapiro, J.I. Regulation of sodium pump endocytosis by cardiotonic steroids: Molecular mechanisms and physiological implications. Pathophysiology 2007, 14, 171–181, . [CrossRef]

- Bagrov, A.Y.; I Shapiro, J. Endogenous digitalis: pathophysiologic roles and therapeutic applications. Nat. Clin. Pr. Nephrol. 2008, 4, 378–392, . [CrossRef]

- Agunanne, E.; Horvat, D.; Harrison, R.; Uddin, M.; Jones, R.; Kuehl, T.; Ghanem, D.; Berghman, L.; Lai, X.; Li, J.; et al. Marinobufagenin Levels in Preeclamptic Patients: A Preliminary Report. Am. J. Perinatol. 2011, 28, 509–514, . [CrossRef]

- Averina IV, Tapilskaya NI, Reznik VA, Frolova EV, Fedorova OV, Lakatta EG, Bagrov AY. Endogenous Na/K-ATPase inhibitors in patients with preeclampsia. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2006; 52:19–23.

- Lopatin DA, Ailamazian EK, Dmitrieva RI, Shpen VM, Fedorova OV, Doris PA, Bagrov AY. Circulating bufadienolide and cardenolide sodium pump inhibitors in preeclampsia. J Hypertens. 1999; 17:1179–1187.

- Abi-Ghanem, D.; Lai, X.; Berghman, L.R.; Horvat, D.; Li, J.; Romo, D.; Uddin, M.N.; Kamano, Y.; Nogawa, T.; Xu, J.-P.; et al. A CHEMIFLUORESCENT IMMUNOASSAY FOR THE DETERMINATION OF MARINOBUFAGENIN IN BODY FLUIDS. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 2011, 32, 31–46, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Horvat, D.; Childs, E.W.; Puschett, J.B. Marinobufagenin causes endothelial cell monolayer hyperpermeability by altering apoptotic signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R1726–R1734, . [CrossRef]

- Ehrig JC, Horvat D, Allen SR, Jones RO, Kuehl TJ, Uddin MN. Cardiotonic steroids induce anti-angiogenic and anti-proliferative profiles in first trimester extravillous cytotrophoblast cells. Placenta. 2014; 35:932-936.

- Uddin, M.; Horvat, D.; Glaser, S.; Danchuk, S.; Mitchell, B.; Sullivan, D.; Morris, C.; Puschett, J. Marinobufagenin Inhibits Proliferation and Migration of Cytotrophoblast and CHO Cells. Placenta 2008, 29, 266–273, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Horvat, D.; Glaser, S.S.; Mitchell, B.M.; Puschett, J.B. Examination of the Cellular Mechanisms by Which Marinobufagenin Inhibits Cytotrophoblast Function. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 17946–17953, . [CrossRef]

- Ehrig JC, Afroze SH, Reyes M, Allen SR, Drever NS, Pilkinton KA, Kuehl TJ, Uddin MN. A p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor attenuates cardiotonic steroids-induced apoptotic and stress signaling in a Sw-71 cytotrophoblast cell line. Placenta. 2015; 36:1276-1282.

- Bagrov, A.Y.; Fedorova, O.V. Effects of two putative endogenous digitalis-like factors, marinobufagenin and ouabain, on the Na+,K+-pump in human mesenteric arteries. J. Hypertens. 1998, 16, 1953–1958, . [CrossRef]

- Puschett, J.B. The role of excessive volume expansion in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Med Hypotheses 2006, 67, 1125–1132, . [CrossRef]

- Ianosi-Irimie M, Vu HV, Whitbred JM, Pridjian CA, Nadig JD, Williams MY, Wrenn DC, Pridjian G, Puschett JB. A rat model of preeclampsia. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2005; 8:605-617.

- Vu, H.V.; Ianosi-Irimie, M.R.; Pridjian, C.A.; Whitbred, J.M.; Durst, J.M.; Bagrov, A.Y.; Fedorova, O.V.; Pridjian, G.; Puschett, J.B. Involvement of Marinobufagenin in a Rat Model of Human Preeclampsia. Am. J. Nephrol. 2005, 25, 520–528, . [CrossRef]

- Agunanne, E.; Uddin, M.; Horvat, D.; Puschett, J. Contribution of Angiogenic Factors in a Rat Model of Pre-Eclampsia. Am. J. Nephrol. 2010, 32, 332–339, . [CrossRef]

- Adair, C.; Buckalew, V.; Graves, S.; Lam, G.; Johnson, D.; Saade, G.; Lewis, D.; Robinson, C.; Danoff, T.; Chauhan, N.; et al. Digoxin Immune Fab Treatment for Severe Preeclampsia. Am. J. Perinatol. 2010, 27, 655–662, . [CrossRef]

- Goodlin, R.C. Antidigoxin Antibodies in Eclampsia. New Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 518–519, . [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, O.V.; Lakatta, E.G.; Bagrov, A.Y.; Melander, O. Plasma level of the endogenous sodium pump ligand marinobufagenin is related to the salt-sensitivity in men. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 534–541, . [CrossRef]

- Zazerskaya IE, Ishkaraeva VV, Frolova EV, Solodovnikova NG, Grigorova YN, David Adair C, Fedorova OV, Bagrov AY. Magnesium sulfate potentiates effect of DigiFab on marinobufagenin-induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition. Am J Hypertens. 2013; 26(11):1269-1272.

- Ishkaraeva-Yakovleva VV, Fedorova OV, Solodovnikova NG, Frolova EV, Bzhelyansky AM, Emelyanov IV, Adair CD, Zazerskaya IE, Bagrov AY. DigiFab interacts with endogenous cardiotonic steroids and reverses preeclampsia-induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition. Reprod Sci. 2012; 19(12):1260-1267.

- Fedorova OV, Simbirtsev AS, Kolodkin NI, et al. Monoclonal antibody to an endogenous bufadienolide, marinobufagenin, reverses preeclampsia-induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition and lowers blood pressure in NaCl-sensitive hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008; 26:2414-2425.

- Horvat, D.; Severson, J.; Uddin, M.; Mitchell, B.; Puschett, J. Resibufogenin Prevents the Manifestations of Preeclampsia in an Animal Model of the Syndrome. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2009, 1–9, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Agunanne, E.; Horvat, D.; Puschett, J.B. Alterations in the Renin-Angiotensin System in a Rat Model of Human Preeclampsia. Am. J. Nephrol. 2009, 31, 171–177, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Agunanne, E.E.; Horvat, D.; Puschett, J.B. Resibufogenin Administration Prevents Oxidative Stress in a Rat Model of Human Preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2010, 31, 70–78, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Horvat, D.; DeMorrow, S.; Agunanne, E.; Puschett, J.B. Marinobufagenin is an upstream modulator of Gadd45a stress signaling in preeclampsia. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2011, 1812, 49–58, . [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, O.V.; Kolodkin, N.I.; Agalakova, N.I.; Namikas, A.R.; Bzhelyansky, A.; St-Louis, J.; Lakatta, E.G.; Bagrov, A.Y. Antibody to marinobufagenin lowers blood pressure in pregnant rats on a high NaCl intake. J. Hypertens. 2005, 23, 835–842, doi:10.1097/01.hjh.0000163153.27954.33.

- Fedorova OV, Simbirtsev AS, Kolodkin NI, Kotov AY, Agalakova NI, Kashkin VA, Tapilskaya NI, Bzhelyansky A, Reznik VA, Frolova EV, Nikitina ER, Budny GV, Longo DL, Lakatta EG, Bagrov AY. Monoclonal antibody to an endogenous bufadienolide, marinobufagenin, reverses preeclampsia- induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition and lowers blood pressure in NaCl-sensitive hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008; 26:2414–25.

- Horvat D, Severson J, Uddin MN, Mitchell B, Puschett JB. Resibufogenin prevents the manifestation of preeclampsia in an animal model of the syndrome. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2010; 29:1-9.

- Queen, C.; Schneider, W.P.; E Selick, H.; Payne, P.W.; Landolfi, N.F.; Duncan, J.F.; Avdalovic, N.M.; Levitt, M.; Junghans, R.P.; A Waldmann, T. A humanized antibody that binds to the interleukin 2 receptor.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989, 86, 10029–10033, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; McLean, L.B.; Hunter, F.A.; Horvat, D.; Severson, J.; Tharakan, B.; Childs, E.W.; Puschett, J.B. Vascular Leak in a Rat Model of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Nephrol. 2009, 30, 26–33, . [CrossRef]

- Puschett, J.B. Marinobufagenin Predicts and Resibufogenin Prevents Preeclampsia: A Review of the Evidence. Am. J. Perinatol. 2012, 29, 777–786, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Horvat, D.; Childs, E.W.; Puschett, J.B. Marinobufagenin causes endothelial cell monolayer hyperpermeability by altering apoptotic signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R1726–R1734, . [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Allen, S.R.; Jones, R.O.; Zawieja, D.C.; Kuehl, T.J. Pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia: marinobufagenin and angiogenic imbalance as biomarkers of the syndrome. Transl. Res. 2012, 160, 99–113, . [CrossRef]

- Fedorova OV, Simbirtsev AS, Kolodkin NI, et al. Monoclonal antibody to an endogenous bufodienolide, marinobufagenin, reverses pre-eclampsia-induced Na/K-ATPase inhibition and lowers blood pressure in NaCl-sensitive hypertension. J Hypertens. 2008; 26:2414–25.

- Uddin MN, Agunanne EE, Horvat D, Puschett JB. Resibufogenin administration prevents oxidative stress in a rat model of human pre-eclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2012; 31:70–8.

- Kennedy, D.J.; Vetteth, S.; Periyasamy, S.M.; Kanj, M.; Fedorova, L.; Khouri, S.; Kahaleh, M.B.; Xie, Z.; Malhotra, D.; Kolodkin, N.I.; et al. Central Role for the Cardiotonic Steroid Marinobufagenin in the Pathogenesis of Experimental Uremic Cardiomyopathy. Hypertension 2006, 47, 488–495, . [CrossRef]

- Elkareh, J.; Periyasamy, S.M.; Shidyak, A.; Vetteth, S.; Schroeder, J.; Raju, V.; Hariri, I.M.; El-Okdi, N.; Gupta, S.; Fedorova, L.; et al. Marinobufagenin induces increases in procollagen expression in a process involving protein kinase C and Fli-1: implications for uremic cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2009, 296, F1219–F1226, . [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.W.; Williams, G.H. An Endogenous Ouabain-Like Factor Associated with Hypertensive Pregnant Women*. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1984, 59, 1070–1074, . [CrossRef]

- Goodlin, R.C. Antidigoxin Antibodies in Eclampsia. New Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 518–519, . [CrossRef]

- Adair CD, Buckalew V, Taylor K, Ernest JM, Frye AH, Evans C, and Veille JC. Elevated endoxin-like factor complicating a multifetal second trimester pregnancy: treatment with digoxin-binding immunoglobulin. Am J Nephrol. 1996; 16:529–531.

- Yart L, Roset Bahmanyar E, Cohen M, Martinez de Tejada B. Role of the uteroplacental renin-angiotensin system in placental development and function, and its implication in the preeclampsia pathogenesis. Biomedicines. 2021; 27:1332.

- Patten AR, Fontaine CJ, Christie BR. A comparison of the different animal models of fetal alcohol spec-trum disorders and their use in studying complex behaviors. Front Pediatr. 2014; 2:93.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).