Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Human Genetics of CRL in NDD Patients

3. Behavioral Phenotypes of Mice with CRL Mutations

4. CRLs in Neural Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation

5. CRLs in Neuronal Polarization

6. CRLs in Neuronal Migration

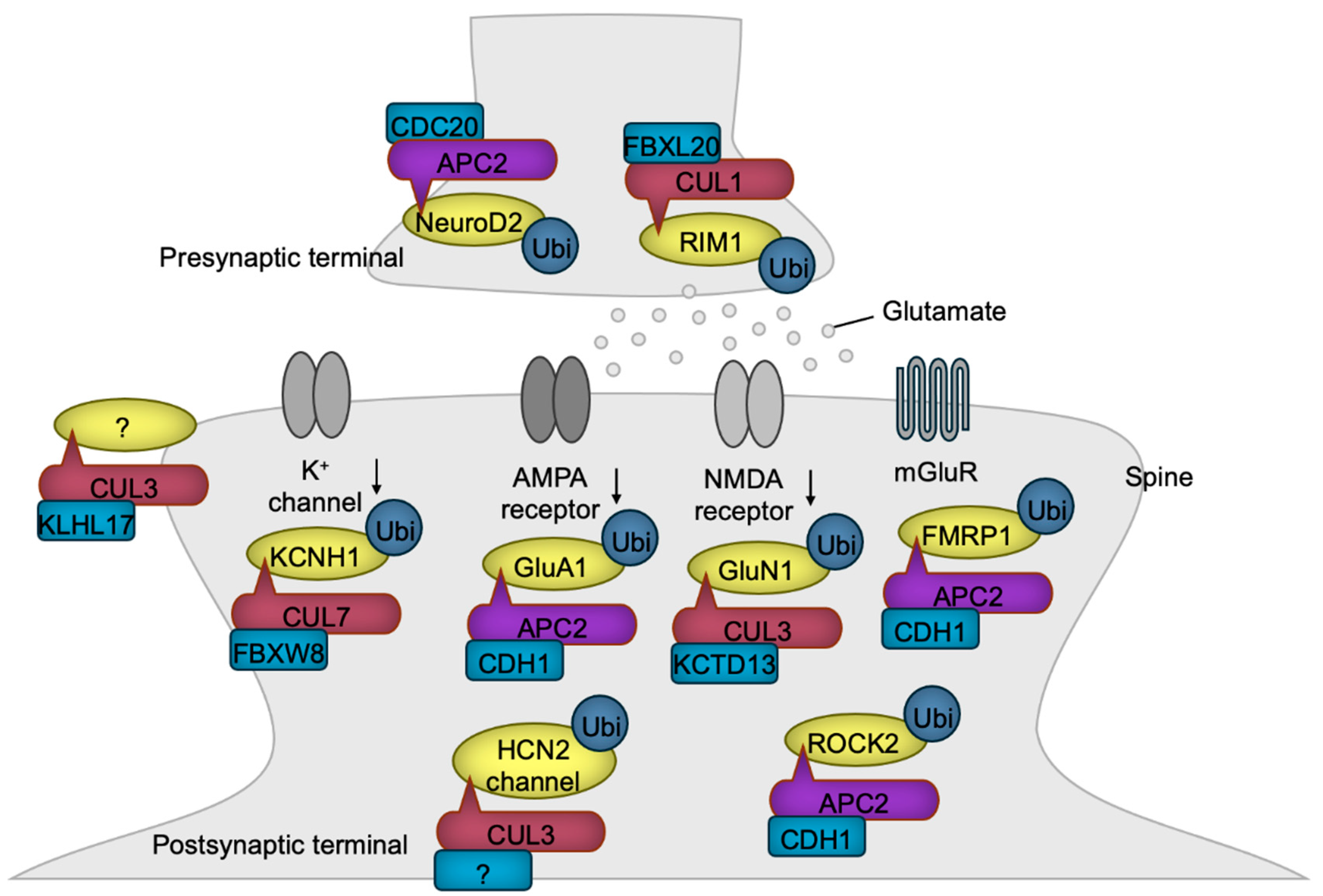

7. CRLs in Synaptogenesis and Synaptic Function

8. Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

9. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Glickman, M.H. and A. Ciechanover, The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev, 2002. 82(2): p. 373-428. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J. and L.J. Sun, Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol Cell, 2009. 33(3): p. 275-86. [CrossRef]

- Hershko, A. and A. Ciechanover, The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem, 1998. 67: p. 425-79.

- Metzger, M.B., V.A. Hristova, and A.M. Weissman, HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J Cell Sci, 2012. 125(Pt 3): p. 531-7. [CrossRef]

- Uchida, C. and M. Kitagawa, RING-, HECT-, and RBR-type E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: Involvement in Human Cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets, 2016. 16(2): p. 157-74.

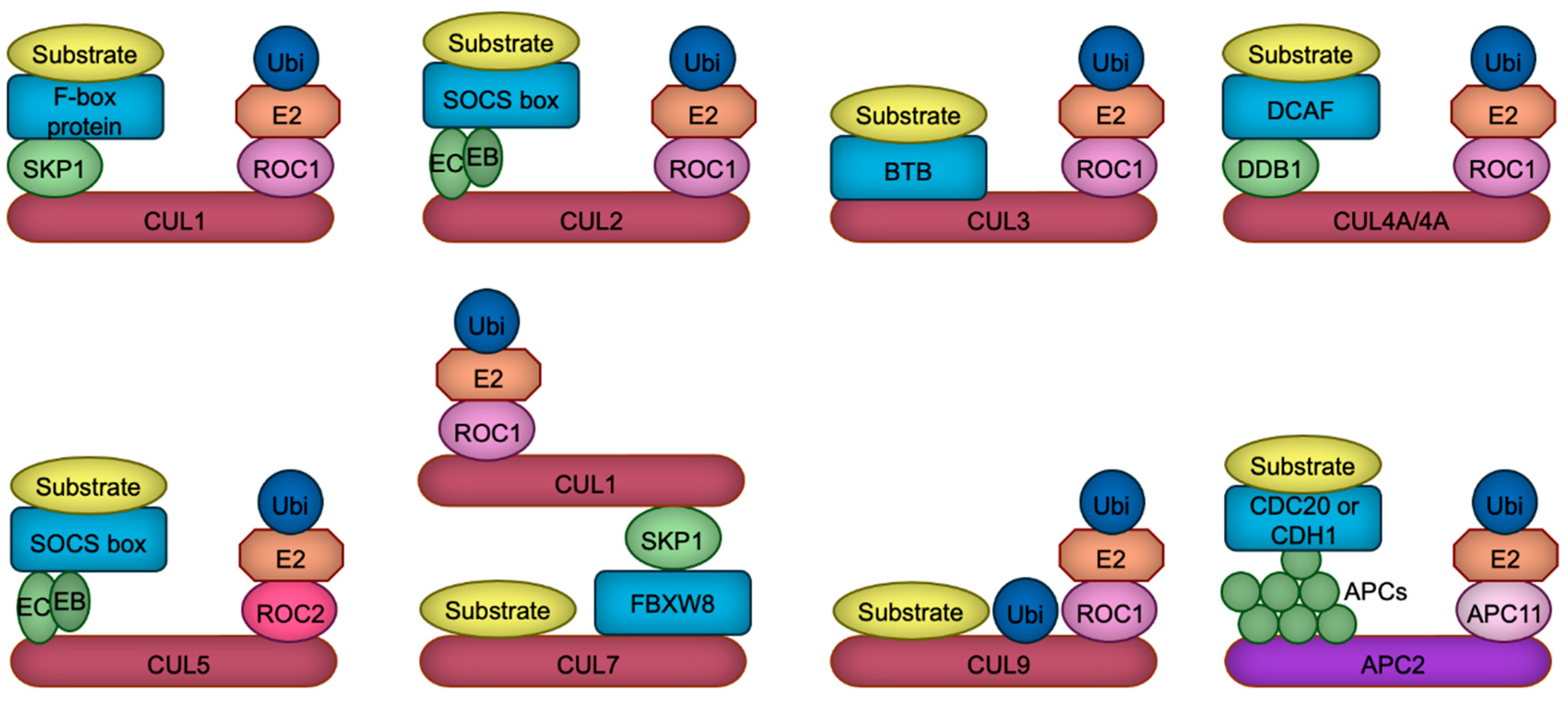

- Petroski, M.D. and R.J. Deshaies, Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2005. 6(1): p. 9-20.

- Harper, J.W. and B.A. Schulman, Cullin-RING Ubiquitin Ligase Regulatory Circuits: A Quarter Century Beyond the F-Box Hypothesis. Annu Rev Biochem, 2021. 90: p. 403-429.

- Skaar, J.R., J.K. Pagan, and M. Pagano, Mechanisms and function of substrate recruitment by F-box proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2013. 14(6): p. 369-81.

- Jackson, S. and Y. Xiong, CRL4s: the CUL4-RING E3 ubiquitin ligases. Trends Biochem Sci, 2009. 34(11): p. 562-70.

- Nakagawa, M. and T. Nakagawa, CUL4-Based Ubiquitin Ligases in Chromatin Regulation: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cells, 2025. 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Hopf, L.V.M., et al., Structure of CRL7(FBXW8) reveals coupling with CUL1-RBX1/ROC1 for multi-cullin-RING E3-catalyzed ubiquitin ligation. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2022. 29(9): p. 854-862.

- Horn-Ghetko, D., et al., Noncanonical assembly, neddylation and chimeric cullin-RING/RBR ubiquitylation by the 1.8 MDa CUL9 E3 ligase complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol, 2024. 31(7): p. 1083-1094.

- Kamura, T., et al., VHL-box and SOCS-box domains determine binding specificity for Cul2-Rbx1 and Cul5-Rbx2 modules of ubiquitin ligases. Genes Dev, 2004. 18(24): p. 3055-65. [CrossRef]

- Yamano, H., APC/C: current understanding and future perspectives. F1000Res, 2019. 8.

- Fuchsberger, T., A. Lloret, and J. Viña, New Functions of APC/C Ubiquitin Ligase in the Nervous System and Its Role in Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 2017. 18(5).

- O'Roak, B.J., et al., Multiplex targeted sequencing identifies recurrently mutated genes in autism spectrum disorders. Science, 2012. 338(6114): p. 1619-22.

- Sanders, S.J., et al., Insights into Autism Spectrum Disorder Genomic Architecture and Biology from 71 Risk Loci. Neuron, 2015. 87(6): p. 1215-1233.

- Tarpey, P.S., et al., Mutations in CUL4B, which encodes a ubiquitin E3 ligase subunit, cause an X-linked mental retardation syndrome associated with aggressive outbursts, seizures, relative macrocephaly, central obesity, hypogonadism, pes cavus, and tremor. Am J Hum Genet, 2007. 80(2): p. 345-52. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y., et al., Mutation in CUL4B, which encodes a member of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase complex, causes X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet, 2007. 80(3): p. 561-6.

- O'Roak, B.J., et al., Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature, 2012. 485(7397): p. 246-50.

- Gregor, A., et al., De Novo Variants in the F-Box Protein FBXO11 in 20 Individuals with a Variable Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Am J Hum Genet, 2018. 103(2): p. 305-316.

- Gregor, A., et al., De novo missense variants in FBXO11 alter its protein expression and subcellular localization. Hum Mol Genet, 2022. 31(3): p. 440-454.

- Schneider, A.L., et al., FBXO28 causes developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with profound intellectual disability. Epilepsia, 2021. 62(1): p. e13-e21.

- Mir, A., et al., Truncation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase component FBXO31 causes non-syndromic autosomal recessive intellectual disability in a Pakistani family. Hum Genet, 2014. 133(8): p. 975-84.

- Harripaul, R., et al., Mapping autosomal recessive intellectual disability: combined microarray and exome sequencing identifies 26 novel candidate genes in 192 consanguineous families. Mol Psychiatry, 2018. 23(4): p. 973-984.

- Ansar, M., et al., Biallelic variants in FBXL3 cause intellectual disability, delayed motor development and short stature. Hum Mol Genet, 2019. 28(6): p. 972-979. [CrossRef]

- Bonnen, P.E., et al., Mutations in FBXL4 cause mitochondrial encephalopathy and a disorder of mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Am J Hum Genet, 2013. 93(3): p. 471-81.

- Gai, X., et al., Mutations in FBXL4, encoding a mitochondrial protein, cause early-onset mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet, 2013. 93(3): p. 482-95.

- Charng, W.L., et al., Exome sequencing in mostly consanguineous Arab families with neurologic disease provides a high potential molecular diagnosis rate. BMC Med Genomics, 2016. 9(1): p. 42.

- Ruzzo, E.K., et al., Inherited and De Novo Genetic Risk for Autism Impacts Shared Networks. Cell, 2019. 178(4): p. 850-866.e26.

- Holt, R.J., et al., De Novo Missense Variants in FBXW11 Cause Diverse Developmental Phenotypes Including Brain, Eye, and Digit Anomalies. Am J Hum Genet, 2019. 105(3): p. 640-657.

- Chau, K.K., et al., Full-length isoform transcriptome of the developing human brain provides further insights into autism. Cell Rep, 2021. 36(9): p. 109631.

- Stephenson, S.E.M., et al., Germline variants in tumor suppressor FBXW7 lead to impaired ubiquitination and a neurodevelopmental syndrome. Am J Hum Genet, 2022. 109(4): p. 601-617.

- Meier-Abt, F., et al., Further evidence that the neurodevelopmental gene FBXW7 predisposes to Wilms tumor. Am J Med Genet A, 2024. 194(6): p. e63528.

- Wang, Y., et al., Case report: A novel FBXW7 gene variant causes global developmental delay. Front Genet, 2024. 15: p. 1436462.

- De Rubeis, S., et al., Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature, 2014. 515(7526): p. 209-15.

- Sleyp, Y., et al., De novo missense variants in the E3 ubiquitin ligase adaptor KLHL20 cause a developmental disorder with intellectual disability, epilepsy, and autism spectrum disorder. Genet Med, 2022. 24(12): p. 2464-2474. [CrossRef]

- Mastrangelo, M., et al., Progressive myoclonus epilepsy and ceroidolipofuscinosis 14: The multifaceted phenotypic spectrum of KCTD7-related disorders. Eur J Med Genet, 2019. 62(12): p. 103591.

- Golzio, C., et al., KCTD13 is a major driver of mirrored neuroanatomical phenotypes of the 16p11.2 copy number variant. Nature, 2012. 485(7398): p. 363-7.

- Clothier, J.L., et al., Identification of DCAF1 by Clinical Exome Sequencing and Methylation Analysis as a Candidate Gene for Autism and Intellectual Disability: A Case Report. J Pers Med, 2022. 12(6).

- Webster, E., et al., De novo PHIP-predicted deleterious variants are associated with developmental delay, intellectual disability, obesity, and dysmorphic features. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud, 2016. 2(6): p. a001172.

- Jansen, S., et al., A genotype-first approach identifies an intellectual disability-overweight syndrome caused by PHIP haploinsufficiency. Eur J Hum Genet, 2018. 26(1): p. 54-63.

- Glessner, J.T., et al., Autism genome-wide copy number variation reveals ubiquitin and neuronal genes. Nature, 2009. 459(7246): p. 569-73.

- Higgins, J.J., et al., A mutation in a novel ATP-dependent Lon protease gene in a kindred with mild mental retardation. Neurology, 2004. 63(10): p. 1927-31.

- Sheereen, A., et al., A missense mutation in the CRBN gene that segregates with intellectual disability and self-mutilating behaviour in a consanguineous Saudi family. J Med Genet, 2017. 54(4): p. 236-240.

- Rodríguez, C., et al., A novel human Cdh1 mutation impairs anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome activity resulting in microcephaly, psychomotor retardation, and epilepsy. J Neurochem, 2019. 151(1): p. 103-115. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sulser, A., Rodent genetic models of neurodevelopmental disorders and epilepsy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2020. 24: p. 66-69.

- Silverman, J.L., et al., Reconsidering animal models used to study autism spectrum disorder: Current state and optimizing future. Genes Brain Behav, 2022. 21(5): p. e12803.

- Damianidou, E., L. Mouratidou, and C. Kyrousi, Research models of neurodevelopmental disorders: The right model in the right place. Front Neurosci, 2022. 16: p. 1031075.

- Takao, K., N. Yamasaki, and T. Miyakawa, Impact of brain-behavior phenotypying of genetically-engineered mice on research of neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Res, 2007. 58(2): p. 124-32.

- Huang, L., et al., Behavioral tests for evaluating the characteristics of brain diseases in rodent models: Optimal choices for improved outcomes (Review). Mol Med Rep, 2022. 25(5).

- Amar, M., et al., Autism-linked Cullin3 germline haploinsufficiency impacts cytoskeletal dynamics and cortical neurogenesis through RhoA signaling. Mol Psychiatry, 2021. 26(7): p. 3586-3613.

- Morandell, J., et al., Cul3 regulates cytoskeleton protein homeostasis and cell migration during a critical window of brain development. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 3058.

- Dong, Z., et al., CUL3 Deficiency Causes Social Deficits and Anxiety-like Behaviors by Impairing Excitation-Inhibition Balance through the Promotion of Cap-Dependent Translation. Neuron, 2020. 105(3): p. 475-490.e6.

- Gao, N., et al., Deficiency of Cullin 3, a Protein Encoded by a Schizophrenia and Autism Risk Gene, Impairs Behaviors by Enhancing the Excitability of Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) DA Neurons. J Neurosci, 2023. 43(36): p. 6249-6267.

- Chen, C.Y., et al., Rescue of the genetically engineered Cul4b mutant mouse as a potential model for human X-linked mental retardation. Hum Mol Genet, 2012. 21(19): p. 4270-85.

- Hu, H.T., T.N. Huang, and Y.P. Hsueh, KLHL17/Actinfilin, a brain-specific gene associated with infantile spasms and autism, regulates dendritic spine enlargement. J Biomed Sci, 2020. 27(1): p. 103. [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, T., et al., Kctd13-deficient mice display short-term memory impairment and sex-dependent genetic interactions. Hum Mol Genet, 2019. 28(9): p. 1474-1486.

- Rajadhyaksha, A.M., et al., Behavioral characterization of cereblon forebrain-specific conditional null mice: a model for human non-syndromic intellectual disability. Behav Brain Res, 2012. 226(2): p. 428-34.

- Li, M., et al., The adaptor protein of the anaphase promoting complex Cdh1 is essential in maintaining replicative lifespan and in learning and memory. Nat Cell Biol, 2008. 10(9): p. 1083-9.

- Bobo-Jiménez, V., et al., APC/C(Cdh1)-Rock2 pathway controls dendritic integrity and memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2017. 114(17): p. 4513-4518.

- Navarro Negredo, P., R.W. Yeo, and A. Brunet, Aging and Rejuvenation of Neural Stem Cells and Their Niches. Cell Stem Cell, 2020. 27(2): p. 202-223.

- Alonso, M., A.C. Petit, and P.M. Lledo, The impact of adult neurogenesis on affective functions: of mice and men. Mol Psychiatry, 2024. 29(8): p. 2527-2542.

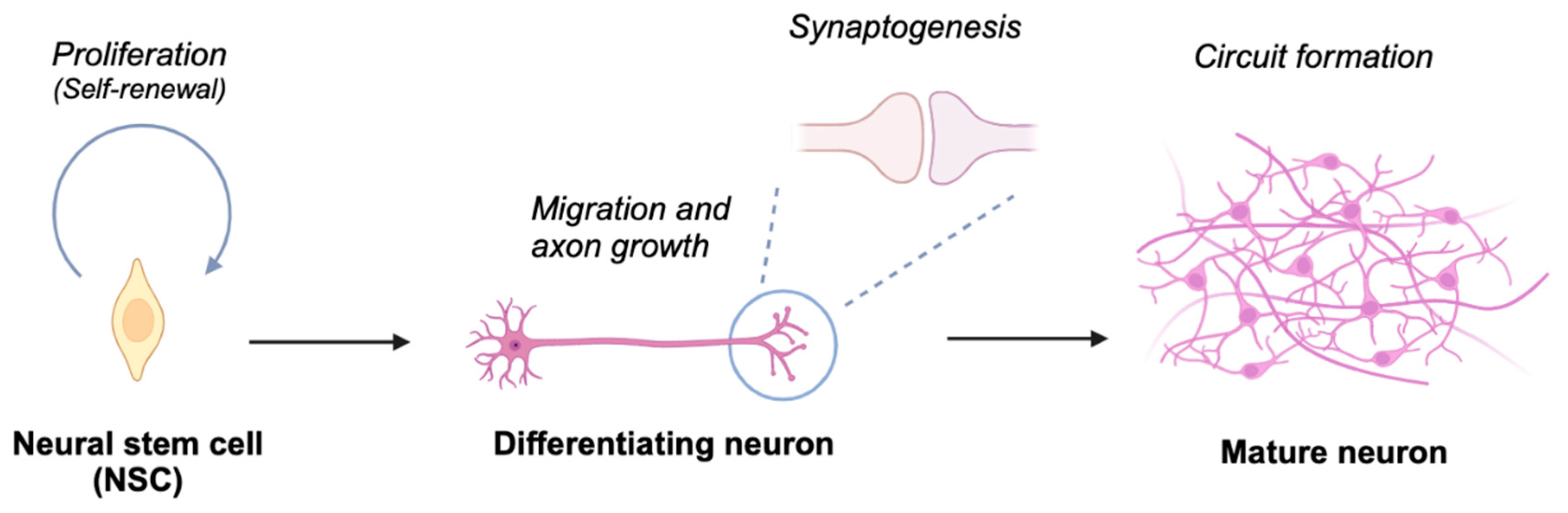

- Florio, M. and W.B. Huttner, Neural progenitors, neurogenesis and the evolution of the neocortex. Development, 2014. 141(11): p. 2182-94.

- Taverna, E., M. Götz, and W.B. Huttner, The cell biology of neurogenesis: toward an understanding of the development and evolution of the neocortex. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 2014. 30: p. 465-502.

- Zhou, Y., H. Song, and G.L. Ming, Genetics of human brain development. Nat Rev Genet, 2024. 25(1): p. 26-45.

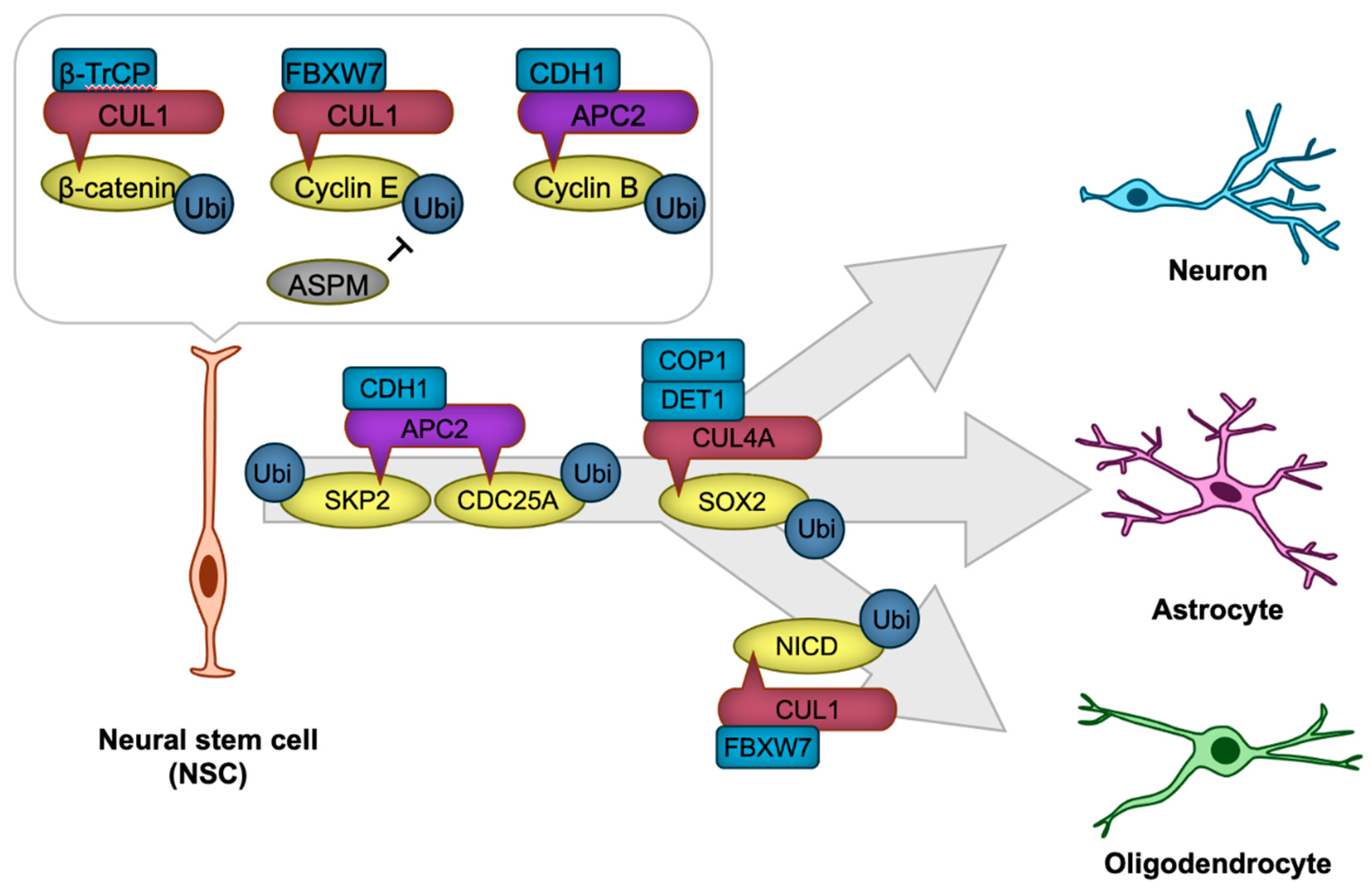

- Pines, J., Cubism and the cell cycle: the many faces of the APC/C. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2011. 12(7): p. 427-38.

- Delgado-Esteban, M., et al., APC/C-Cdh1 coordinates neurogenesis and cortical size during development. Nat Commun, 2013. 4: p. 2879. [CrossRef]

- Capecchi, M.R. and A. Pozner, ASPM regulates symmetric stem cell division by tuning Cyclin E ubiquitination. Nat Commun, 2015. 6: p. 8763.

- Matsumoto, A., et al., Fbxw7-dependent degradation of Notch is required for control of "stemness" and neuronal-glial differentiation in neural stem cells. J Biol Chem, 2011. 286(15): p. 13754-64.

- MacDonald, B.T., K. Tamai, and X. He, Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev Cell, 2009. 17(1): p. 9-26.

- Liu, J., et al., Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2022. 7(1): p. 3.

- Cui, C.P., et al., Dynamic ubiquitylation of Sox2 regulates proteostasis and governs neural progenitor cell differentiation. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 4648.

- Bond, J., et al., Protein-truncating mutations in ASPM cause variable reduction in brain size. Am J Hum Genet, 2003. 73(5): p. 1170-7.

- Létard, P., et al., Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly due to ASPM mutations: An update. Hum Mutat, 2018. 39(3): p. 319-332.

- Arimura, N. and K. Kaibuchi, Neuronal polarity: from extracellular signals to intracellular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2007. 8(3): p. 194-205.

- Yogev, S. and K. Shen, Establishing Neuronal Polarity with Environmental and Intrinsic Mechanisms. Neuron, 2017. 96(3): p. 638-650. [CrossRef]

- Jung, M., D. Kim, and J.Y. Mun, Direct Visualization of Actin Filaments and Actin-Binding Proteins in Neuronal Cells. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020. 8: p. 588556.

- Meka, D.P., et al., Centrosome-dependent microtubule modifications set the conditions for axon formation. Cell Rep, 2022. 39(3): p. 110686.

- Yoshimura, T., N. Arimura, and K. Kaibuchi, Signaling networks in neuronal polarization. J Neurosci, 2006. 26(42): p. 10626-30.

- Lee, Y.R., M. Chen, and P.P. Pandolfi, The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor: new modes and prospects. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2018. 19(9): p. 547-562.

- Christie, K.J., J.A. Martinez, and D.W. Zochodne, Disruption of E3 ligase NEDD4 in peripheral neurons interrupts axon outgrowth: Linkage to PTEN. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2012. 50(2): p. 179-92.

- Drinjakovic, J., et al., E3 ligase Nedd4 promotes axon branching by downregulating PTEN. Neuron, 2010. 65(3): p. 341-57.

- Hsia, H.E., et al., Ubiquitin E3 ligase Nedd4-1 acts as a downstream target of PI3K/PTEN-mTORC1 signaling to promote neurite growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014. 111(36): p. 13205-10.

- Chen, Z., et al., MicroRNA-300 Regulates the Ubiquitination of PTEN through the CRL4B(DCAF13) E3 Ligase in Osteosarcoma Cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids, 2018. 10: p. 254-268.

- Zhang, J., et al., The CRL4-DCAF13 ubiquitin E3 ligase supports oocyte meiotic resumption by targeting PTEN degradation. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2020. 77(11): p. 2181-2197.

- Ge, M.K., et al., FBXO22 degrades nuclear PTEN to promote tumorigenesis. Nat Commun, 2020. 11(1): p. 1720. [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, S., et al., RhoA Controls Axon Extension Independent of Specification in the Developing Brain. Curr Biol, 2019. 29(22): p. 3874-3886.e9.

- Kannan, M., et al., The E3 ligase Cdh1-anaphase promoting complex operates upstream of the E3 ligase Smurf1 in the control of axon growth. Development, 2012. 139(19): p. 3600-12.

- Lin, M.Y., et al., PDZ-RhoGEF ubiquitination by Cullin3-KLHL20 controls neurotrophin-induced neurite outgrowth. J Cell Biol, 2011. 193(6): p. 985-94.

- Dogterom, M. and G.H. Koenderink, Actin-microtubule crosstalk in cell biology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2019. 20(1): p. 38-54.

- Song, J., et al., The X-linked intellectual disability gene product and E3 ubiquitin ligase KLHL15 degrades doublecortin proteins to constrain neuronal dendritogenesis. J Biol Chem, 2021. 296: p. 100082.

- Shim, T., et al., Cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase 4 regulates neurite morphogenesis during neurodevelopment. iScience, 2024. 27(2): p. 108933.

- Stegmüller, J., et al., Cell-intrinsic regulation of axonal morphogenesis by the Cdh1-APC target SnoN. Neuron, 2006. 50(3): p. 389-400.

- Lasorella, A., et al., Degradation of Id2 by the anaphase-promoting complex couples cell cycle exit and axonal growth. Nature, 2006. 442(7101): p. 471-4.

- Nakagawa, T. and Y. Xiong, X-linked mental retardation gene CUL4B targets ubiquitylation of H3K4 methyltransferase component WDR5 and regulates neuronal gene expression. Mol Cell, 2011. 43(3): p. 381-91.

- Nakagawa, T. and Y. Xiong, Chromatin regulation by CRL4 E3 ubiquitin ligases: CUL4B targets WDR5 ubiquitylation in the nucleus, in Cell Cycle. 2011: United States. p. 4197-8.

- Shilatifard, A., The COMPASS family of histone H3K4 methylases: mechanisms of regulation in development and disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Biochem, 2012. 81: p. 65-95.

- Green, E.M. and O. Gozani, CUL4B: trash talking at chromatin. Mol Cell, 2011. 43(3): p. 321-3.

- des Portes, V., et al., A novel CNS gene required for neuronal migration and involved in X-linked subcortical laminar heterotopia and lissencephaly syndrome. Cell, 1998. 92(1): p. 51-61.

- Gleeson, J.G., et al., Doublecortin, a brain-specific gene mutated in human X-linked lissencephaly and double cortex syndrome, encodes a putative signaling protein. Cell, 1998. 92(1): p. 63-72.

- Al-Sarraj, Y., et al., The genetic landscape of autism spectrum disorder in the Middle Eastern population. Front Genet, 2024. 15: p. 1363849.

- Butler, M.G., et al., Subset of individuals with autism spectrum disorders and extreme macrocephaly associated with germline PTEN tumour suppressor gene mutations. J Med Genet, 2005. 42(4): p. 318-21.

- Tan, M.H., et al., A clinical scoring system for selection of patients for PTEN mutation testing is proposed on the basis of a prospective study of 3042 probands. Am J Hum Genet, 2011. 88(1): p. 42-56.

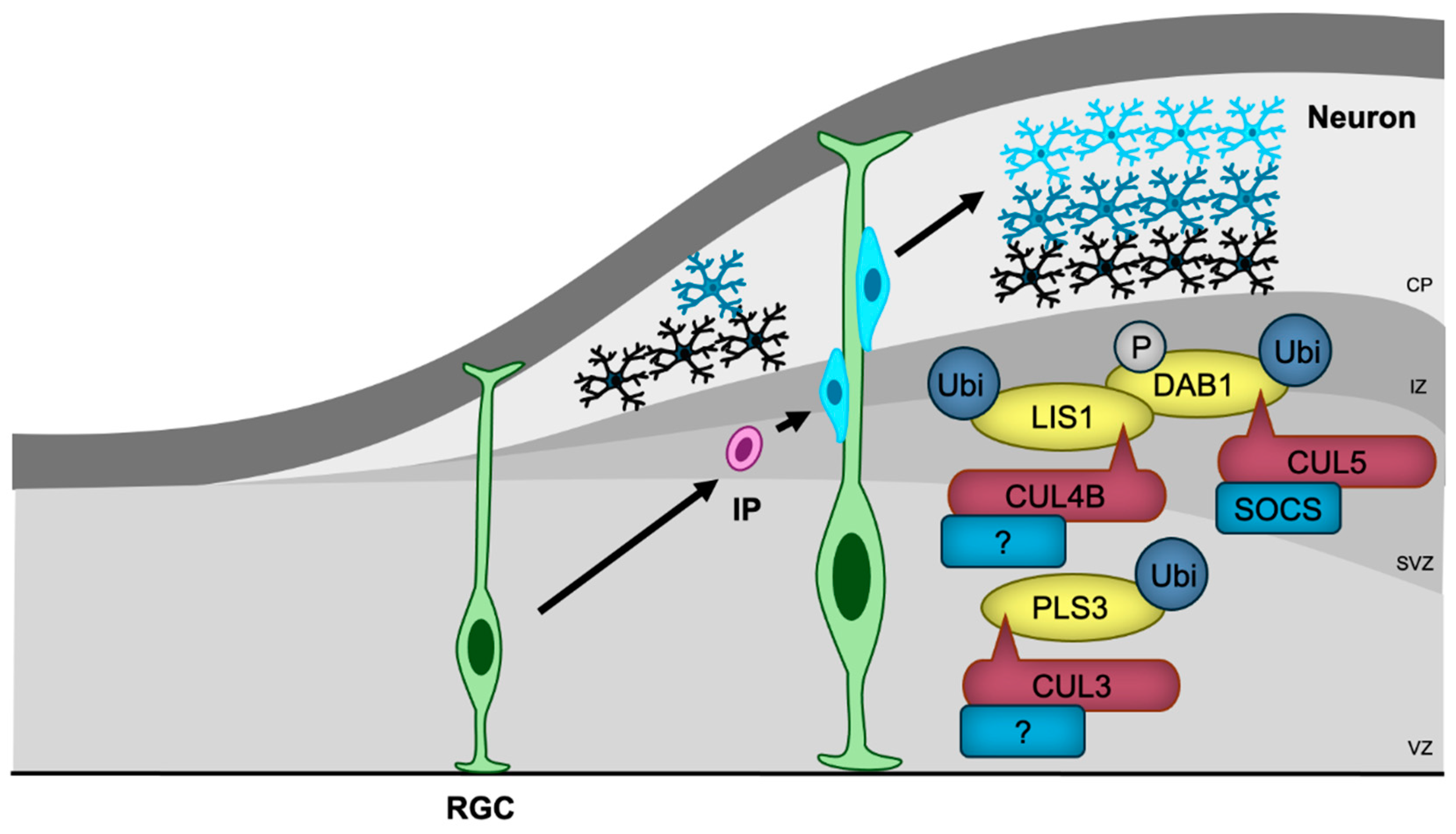

- Agirman, G., L. Broix, and L. Nguyen, Cerebral cortex development: an outside-in perspective. FEBS Lett, 2017. 591(24): p. 3978-3992.

- Jossin, Y., Reelin Functions, Mechanisms of Action and Signaling Pathways During Brain Development and Maturation. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(6).

- Joly-Amado, A., N. Kulkarni, and K.R. Nash, Reelin Signaling in Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Brain Sci, 2023. 13(10).

- Gao, Z. and R. Godbout, Reelin-Disabled-1 signaling in neuronal migration: splicing takes the stage. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2013. 70(13): p. 2319-29.

- Feng, L., et al., Cullin 5 regulates Dab1 protein levels and neuron positioning during cortical development. Genes Dev, 2007. 21(21): p. 2717-30.

- Stier, A., et al., The CUL4B-based E3 ubiquitin ligase regulates mitosis and brain development by recruiting phospho-specific DCAFs. Embo j, 2023. 42(17): p. e112847.

- Butts, T., M.J. Green, and R.J. Wingate, Development of the cerebellum: simple steps to make a 'little brain'. Development, 2014. 141(21): p. 4031-41.

- Cossart, R. and R. Khazipov, How development sculpts hippocampal circuits and function. Physiol Rev, 2022. 102(1): p. 343-378.

- Mukherjee, C., et al., Loss of the neuron-specific F-box protein FBXO41 models an ataxia-like phenotype in mice with neuronal migration defects and degeneration in the cerebellum. J Neurosci, 2015. 35(23): p. 8701-17.

- Quadros, A., et al., Neuronal F-Box protein FBXO41 regulates synaptic transmission and hippocampal network maturation. iScience, 2022. 25(4): p. 104069.

- King, C.R., et al., Fbxo41 Promotes Disassembly of Neuronal Primary Cilia. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 8179.

- Persico, A.M., et al., Reelin gene alleles and haplotypes as a factor predisposing to autistic disorder. Mol Psychiatry, 2001. 6(2): p. 150-9.

- Skaar, D.A., et al., Analysis of the RELN gene as a genetic risk factor for autism. Mol Psychiatry, 2005. 10(6): p. 563-71.

- Nawa, Y., et al., Rare single-nucleotide DAB1 variants and their contribution to Schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder susceptibility. Hum Genome Var, 2020. 7(1): p. 37.

- Saillour, Y., et al., LIS1-related isolated lissencephaly: spectrum of mutations and relationships with malformation severity. Arch Neurol, 2009. 66(8): p. 1007-15.

- Südhof, T.C., Towards an Understanding of Synapse Formation. Neuron, 2018. 100(2): p. 276-293.

- Qi, C., et al., Molecular mechanisms of synaptogenesis. Front Synaptic Neurosci, 2022. 14: p. 939793.

- Kaizuka, T. and T. Takumi, Postsynaptic density proteins and their involvement in neurodevelopmental disorders. J Biochem, 2018. 163(6): p. 447-455.

- Yang, Y., et al., A Cdc20-APC ubiquitin signaling pathway regulates presynaptic differentiation. Science, 2009. 326(5952): p. 575-8.

- Kawabe, H. and J. Stegmüller, The role of E3 ubiquitin ligases in synapse function in the healthy and diseased brain. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2021. 112: p. 103602.

- Yao, I., et al., SCRAPPER-dependent ubiquitination of active zone protein RIM1 regulates synaptic vesicle release. Cell, 2007. 130(5): p. 943-57.

- Hansen, K.B., et al., Structure, Function, and Pharmacology of Glutamate Receptor Ion Channels. Pharmacol Rev, 2021. 73(4): p. 298-487.

- Niswender, C.M. and P.J. Conn, Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2010. 50: p. 295-322.

- Fu, A.K., et al., APC(Cdh1) mediates EphA4-dependent downregulation of AMPA receptors in homeostatic plasticity. Nat Neurosci, 2011. 14(2): p. 181-9.

- Malenka, R.C. and M.F. Bear, LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron, 2004. 44(1): p. 5-21.

- Huang, J., et al., A Cdh1-APC/FMRP Ubiquitin Signaling Link Drives mGluR-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity in the Mammalian Brain. Neuron, 2015. 86(3): p. 726-39.

- Gu, J., et al., KCTD13-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of GluN1 regulates excitatory synaptic transmission and seizure susceptibility. Cell Death Differ, 2023. 30(7): p. 1726-1741.

- Mandic-Maravic, V., et al., Dopamine in Autism Spectrum Disorders-Focus on D2/D3 Partial Agonists and Their Possible Use in Treatment. Front Psychiatry, 2021. 12: p. 787097.

- Pavăl, D., The dopamine hypothesis of autism spectrum disorder: A comprehensive analysis of the evidence. Int Rev Neurobiol, 2023. 173: p. 1-42.

- Maljevic, S. and H. Lerche, Potassium channels: a review of broadening therapeutic possibilities for neurological diseases. J Neurol, 2013. 260(9): p. 2201-11.

- Simons, C., et al., Mutations in the voltage-gated potassium channel gene KCNH1 cause Temple-Baraitser syndrome and epilepsy. Nat Genet, 2015. 47(1): p. 73-7.

- Kortüm, F., et al., Mutations in KCNH1 and ATP6V1B2 cause Zimmermann-Laband syndrome. Nat Genet, 2015. 47(6): p. 661-7.

- Hsu, P.H., et al., Cullin 7 mediates proteasomal and lysosomal degradations of rat Eag1 potassium channels. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 40825.

- Rochefort, N.L. and A. Konnerth, Dendritic spines: from structure to in vivo function. EMBO Rep, 2012. 13(8): p. 699-708.

- Soucy, T.A., et al., An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature, 2009. 458(7239): p. 732-6.

- Li, T., et al., CRISPR/Cas9 therapeutics: progress and prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023. 8(1): p. 36.

- Shi, Y., et al., Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: a decade of progress. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2017. 16(2): p. 115-130.

- Zhou, H., et al., Selective inhibition of cullin 3 neddylation through covalent targeting DCN1 protects mice from acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 2621.

- Wu, K., et al., Inhibitors of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase 4 with antitumor potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2021. 118(8).

| Target disrupted | Behavioral abnormality | Reference | ||||

| Gene | Cell type | Communication | Learning and memory | Hyperactivity | Anxiety | |

| Cul3 | Whole body | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | (-) | [52,53] |

| Cul3 | Neurons and astrocytes | ✔ | (-) | (-) | ✔ | [54] |

| Cul3 | DA neurons | N.T. | ✔ | ✔ | (-) | [55] |

| Cul4b | Whole body | (-) | ✔ | (-) | (-) | [56] |

| Klhl17 | Whole body | ✔ | N.T. | ✔ | (-) | [57] |

| Kctd13 | Whole body | (-) | ✔ | (-) | (-) | [58] |

| Crbn | Forebrain Glu neurons | N.T. | ✔ | (-) | (-) | [59] |

| Cdh1 | Whole body | N.T. | ✔ | N.T. | N.T. | [60] |

| Cdh1 | Forebrain Glu neurons | N.T. | ✔ | (-)* | ✔ | [61] |

| CRL scaffold | Substrate receptor | Substrate | Function | Reference |

| APC/C | CDH1 | Cyclin B | Promotion of NSC proliferation | [68] |

| CUL1 | FBXW7 | Cyclin E | Inhibition of NSC proliferation | [69] |

| CUL1 | FBXW7 | NICD | Promotion of NSC differentiation | [70] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | CDC25A | Promotion of NSC differentiation | [68] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | SKP2 | Promotion of NSC differentiation | [68] |

| CUL1 | β-TrCP | β-Catenin | Promotion of NSC differentiation | [72] |

| CUL4A | DET1-COP1 | SOX2 | Promotion of NSC differentiation | [73] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | SMURF1 | Promotion of dendritogenesis | [89] |

| CUL3 | KLHL20 | PDZ-RhoGEF | Inhibition of axon formation | [90] |

| CUL3 | KLHL15 | DCX | Inhibition of axon/dendrite complexity | [92] |

| CUL4A | CRBN | DCX | Inhibition of axon/dendrite complexity | [93] |

| CUL4B | CRBN | DCX | Inhibition of axon/dendrite complexity | [93] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | SnoN | Inhibition of axon formation | [94] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | ID2 | Inhibition of axon formation | [95] |

| CUL4B | (-)* | WDR5 | Promotion of neurite extension | [96] |

| CUL5 | SOCS | DAB1 | Inhibition of neuronal migration | [109] |

| CUL3 | Unknown | PLS3 | Promotion of neuronal migration | [53] |

| APC/C | CDC20 | NeuroD2 | Promotion of presynapse formation | [123] |

| CUL1 | FBXL20 | RIM1 | Inhibition of postsynaptic function | [125] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | GluA1 | Inhibition of excess synaptic activity | [128] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | FMRP1 | Promotion of LTD | [130] |

| CUL3 | KCTD13 | GluN1 | Inhibition of excess synaptic activity | [131] |

| CUL3 | Unknown | HCN2 | Inhibition of excess synaptic activity | [55] |

| CUL7 | FBXW8 | Kv10.1 | Inhibition of potassium current | [137] |

| CUL3 | KLHL17 | Unknown | Promotion of synaptic activity | [57] |

| APC/C | CDH1 | ROCK2 | Destabilization of dendritic spines | [61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).