Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

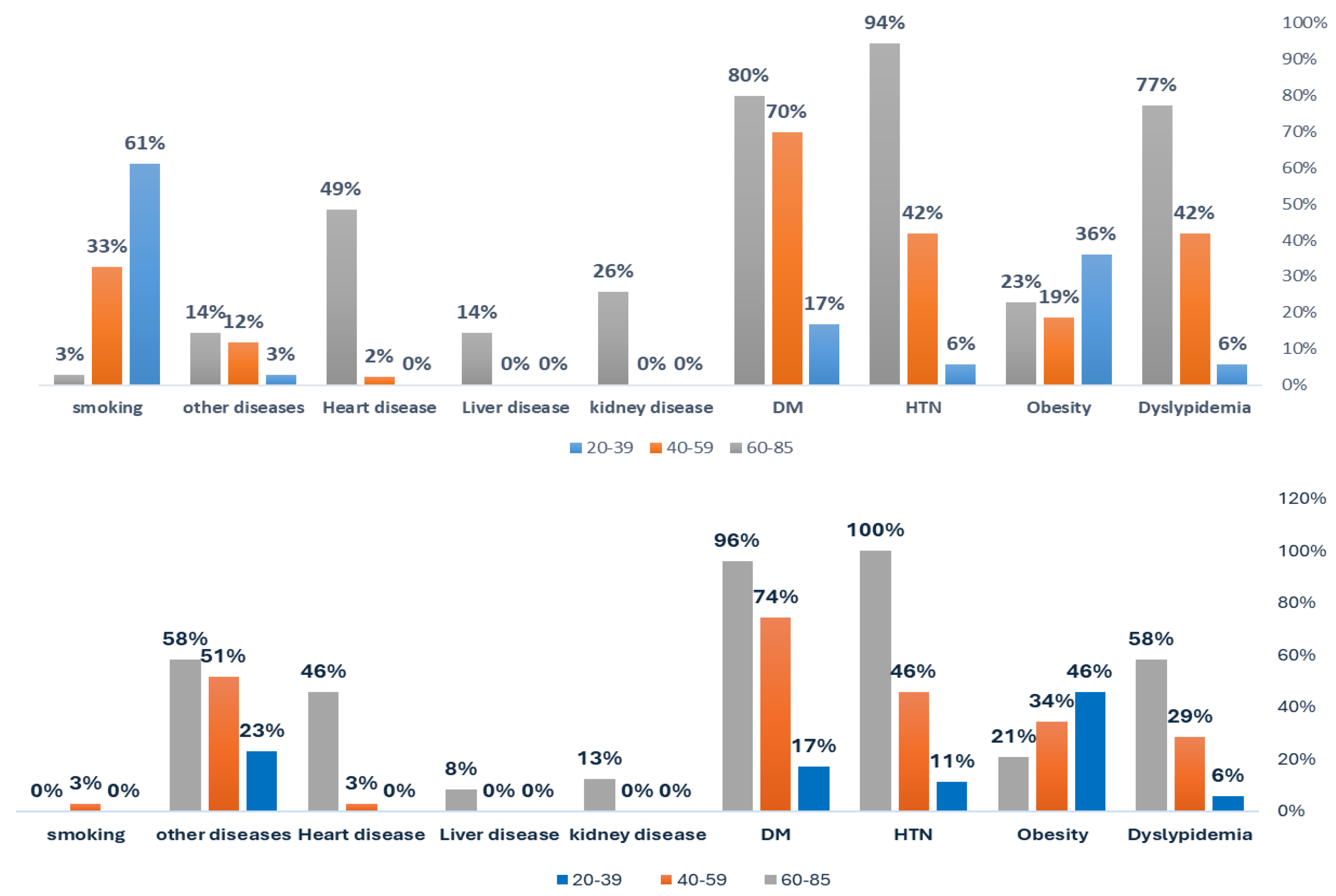

Background/Objectives: Non-communicable diseases like obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and hypertension (HTN) impose major global burdens. Helicobacter pylori infection may worsen these conditions. This study examined the clinical, age-, and gender-specific profiles of H. pylori-infected inpatients and its association with dyslipidemia, obesity, HTN, DM, and other chronic conditions. Methods: Between September 2024 and February 2025, patients were tested using a stool antigen assay (SIMA CHECK–ACON BIOTEC). Demographic data, smoking status, and clinical diagnoses (including kidney, liver, and heart disease) were obtained from hospital records and confirmed with standard criteria. Associations were analyzed using chi-square/Fisher’s tests and logistic regression (adjusted for age, gender, and smoking). Results: Overall, 30.7% (64/208) of inpatients were H. pylori–positive, highest in middle-aged females (42.9%) and lowest in middle-aged males (20.9%). Dyslipidemia rose sharply in males (5.6%→77.1%) versus females (5.7%→58.3%), with infection modestly elevating rates (OR=1.648). Obesity declined with age (males: 36.1%→22.9%; females: 45.7%→20.8%) yet strongly correlated with H. pylori (OR=19.217). HTN (5.6–94.3% in males; 11.4–100% in females) and DM (16.7–80% vs. 17.1–95.8%) increased with age but showed no infection link reflecting inflammatory preference. Smoking peaked at 61.1% in younger males. Kidney and heart diseases appeared only in ages 60–85. Overall, the prevalence of comorbidities markedly increased with age. Conclusion: H. pylori infection is common among inpatients, particularly in middle-aged females, and is significantly linked to dyslipidemia and obesity. These findings support targeted screening, especially in females and individuals with metabolic abnormalities, while future studies should assess whether eradication therapy can mitigate chronic metabolic risks.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Work Environment: Ha’il Province, City, and all Socio-Economic Strata

3. Results

Overall Demographics

Age, Gender, and Chronic Syndromes

Age-, and Gender-Specificity of H. pylori and Association to Obesity and Dyslipidemia

Association of H. pylori Infection with Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Heart, Kidney, and Liver Disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kazibwe J, Tran PB, Annerstedt KS. The household financial burden of non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2021;19(1):96.

- Buzás, GM. Metabolic consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection and eradication. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(18):5226-34.

- Asmelash D, Nigatie M, Melak T, Alemayehu E, Ashagre A, Worede A. Metabolic syndrome and associated factors among H. pylori-infected and negative controls in Northeast Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024;15.

- Murray DM, DuPont HL, Cooperstock M, Corrado ML, Fekety R. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease associated with infection by Helicobacter pylori. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Food and Drug Administration. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15 Suppl 1:S268-73.

- Ruggiero, P. Helicobacter pylori and inflammation. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(38):4225-36.

- Rebora A, Drago F, Parodi A. May Helicobacter pylori be important for dermatologists? Dermatology. 1995;191(1):6-8.

- Wands DIF, El-Omar EM, Hansen R. Helicobacter pylori: getting to grips with the guidance. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2021;12(7):650-5.

- Brown, LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22(2):283-97.

- Franceschi F, Gasbarrini A, Polyzos SA, Kountouras J. Extragastric Diseases and Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2015;20 Suppl 1:40-6.

- Gravina AG, Zagari RM, De Musis C, Romano L, Loguercio C, Romano M. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases: A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(29):3204-21.

- Pellicano R, Ianiro G, Fagoonee S, Settanni CR, Gasbarrini A. Review: Extragastric diseases and Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2020;25 Suppl 1:e12741.

- Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Zavos C, Deretzi G. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and insulin resistance: a systematic review. Helicobacter. 2011;16(2):79-88.

- Zhou X, Liu W, Gu M, Zhou H, Zhang G. Helicobacter pylori infection causes hepatic insulin resistance by the c-Jun/miR-203/SOCS3 signaling pathway. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(10):1027-40.

- Longo-Mbenza B, Nsenga JN, Mokondjimobe E, Gombet T, Assori IN, Ibara JR, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is identified as a cardiovascular risk factor in Central Africans. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2012;6:455-61.

- Fan N, Peng L, Xia Z, Zhang L, Wang Y, Peng Y. Helicobacter pylori Infection Is Not Associated with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:73.

- Jeffery PL, McGuckin MA, Linden SK. Endocrine impact of Helicobacter pylori: focus on ghrelin and ghrelin o-acyltransferase. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(10):1249-60.

- Ferro A, Morais S, Pelucchi C, Aragonés N, Kogevinas M, López-Carrillo L, et al. Smoking and Helicobacter pylori infection: an individual participant pooled analysis (Stomach Cancer Pooling- StoP Project). Eur J Cancer Prev. 2019;28(5):390-6.

- Wang YK, Kuo FC, Liu CJ, Wu MC, Shih HY, Wang SS, et al. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection: Current options and developments. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(40):11221-35.

- Shah SC, Halvorson AE, Lee D, Bustamante R, McBay B, Gupta R, et al. Helicobacter pylori Burden in the United States According to Individual Demographics and Geography: A Nationwide Analysis of the Veterans Healthcare System. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22(1):42-50.e26.

- Liu ZC, Li WQ. Large-scale cluster randomised trial reveals effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication for gastric cancer prevention. Clin Transl Med. 2025;15(2):e70229.

- Azami M, Baradaran HR, Dehghanbanadaki H, Kohnepoushi P, Saed L, Moradkhani A, et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with the risk of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2021;13(1):145.

- He C, Yang Z, Lu NH. Helicobacter pylori infection and diabetes: is it a myth or fact? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(16):4607-17.

- Chua W-K, Hong Y-K, Hu S-W, Fan H-C, Ting W-H. A Significant Association between Type 1 Diabetes and Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Meta-Analysis Study. Medicina [Internet]. 2024; 60(1).

- Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(7):868-76.

- Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420-9.

- Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, Liou JM, Peek R, Schulz C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):19.

- Almashhadany DA, Mayas SM, Mohammed HI, Hassan AA, Khan IUH. Population- and Gender-Based Investigation for Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Dhamar, Yemen. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2023;2023(1):3800810.

- Dias Sara P, Brouwer Matthijs C, van de Beek D. Sex and Gender Differences in Bacterial Infections. Infection and Immunity. 2022;90(10):e00283-22.

- Khan, AR. An age- and gender-specific analysis of H. Pylori infection. Ann Saudi Med. 1998;18(1):6-8.

- Hong W, Tang H, Dong X, Hu S, Yan Y, Basharat Z, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in a third-tier Chinese city: relationship with gender, age, birth-year and survey years. Microb Health Dis. 2019;1:e150.

- Rosu OM, Gimiga N, Stefanescu G, Anton C, Paduraru G, Tataranu E, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection in a Pediatric Population from Romania: Risk Factors, Clinical and Endoscopic Features and Treatment Compliance. J Clin Med. 2022;11(9).

- Chen J, Bu XL, Wang QY, Hu PJ, Chen MH. Decreasing seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection during 1993-2003 in Guangzhou, southern China. Helicobacter. 2007;12(2):164-9.

- den Hoed CM, Vila AJ, Holster IL, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, de Jongste JC, et al. Helicobacter pylori and the birth cohort effect: evidence for stabilized colonization rates in childhood. Helicobacter. 2011;16(5):405-9.

- Graham, DY. Helicobacter pylori: its epidemiology and its role in duodenal ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6(2):105-13.

- Wroblewski LE, Peek RM, Jr., Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):713-39.

- Abdu A, Cheneke W, Adem M, Belete R, Getachew A. Dyslipidemia and Associated Factors Among Patients Suspected to Have Helicobacter pylori Infection at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma, Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:311-21.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735-52.

- Hashim M, Mohammed O, T GE, Wolde M. The association of Helicobacter Pylori infection with dyslipidaemia and other atherogenic factors in dyspeptic patients at St. Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College. Heliyon. 2022;8(5):e09430.

- Khera AV, Demler OV, Adelman SJ, Collins HL, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM, et al. Cholesterol Efflux Capacity, High-Density Lipoprotein Particle Number, and Incident Cardiovascular Events: An Analysis From the JUPITER Trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin). Circulation. 2017;135(25):2494-504.

- Vijayvergiya R, Vadivelu R. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. World J Cardiol. 2015;7(3):134-43.

- Morningstar-Wright L, Czinn SJ, Piazuelo MB, Banerjee A, Godlewska R, Blanchard TG. The TNF-Alpha Inducing Protein is Associated With Gastric Inflammation and Hyperplasia in a Murine Model of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:817237.

- Liu S, Zhang N, Ji X, Yang S, Zhao Z, Li P. Helicobacter pylori CagA promotes gastric cancer immune escape by upregulating SQLE. Cell Death & Disease. 2025;16(1):17.

- Chen L-W, Kuo S-F, Chen C-H, Chien C-H, Lin C-L, Chien R-N. A community-based study on the association between Helicobacter pylori Infection and obesity. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):10746.

- Kamarehei F, Mohammadi Y. The Effect of Helicobacter pylori Infection on Overweight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2022;51(11):2417-24.

- Liu Y, Shuai P, Chen W, Liu Y, Li D. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and metabolic syndrome and its components. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1188487.

- Jeon CY, Haan MN, Cheng C, Clayton ER, Mayeda ER, Miller JW, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with an increased rate of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):520-5.

- Pan W, Zhang H, Wang L, Zhu T, Chen B, Fan J. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and kidney damage in patients with peptic ulcer. Renal Failure. 2019;41(1):1028-34.

- Abo-Amer YE, Sabal A, Ahmed R, Hasan NFE, Refaie R, Mostafa SM, et al. Relationship Between Helicobacter pylori Infection and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) in a Developing Country: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:619-25.

- Aramouni K, Assaf RK, Azar M, Jabbour K, Shaito A, Sahebkar A, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori may predispose to atherosclerosis: role of inflammation and thickening of intima-media of carotid arteries. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1285754.

- Addissouky TA, El Sayed IET, Ali MMA, Wang Y, El Baz A, Elarabany N, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation: elucidating mechanisms of smoking-attributable pathology for therapeutic targeting. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 2024;48(1):16.

- Elghannam MT, Hassanien MH, Ameen YA, Turky EA, Elattar GM, Elray AA, et al. Helicobacter pylori and oral–gut microbiome: clinical implications. Infection. 2024;52(2):289-300.

- Zhang L, Zhao M, Fu X. Gastric microbiota dysbiosis and Helicobacter pylori infection. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1153269.

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1027-31.

- Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101(44):15718-23.

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male 5(N=114; 54.8%) |

Female 5(N=94; 45.2%) |

||||||||||||

| Age | Age | ||||||||||||

| 20-39 (n=36) | 40-59 (n=43) | 60-85 (n=35) | 20-39 (n=35) | 40-59 (n=35) | 60-85 (n=24) | ||||||||

| N | N % | N | N % | N | N % | N | N % | N | N % | N | N % | ||

| Dyslypidemia (m/f: 64.4M, 35.6%F) | no | 34 | 94.4% | 25 | 58.1% 5 |

8 | 22.9% | 33 | 94.3% | 25 | 71.4% 5 |

10 | 41.7% |

| yes | 2 | 5.6% | 18 | 41.9% | 27 | 77.1% | 2 | 5.7% | 10 | 28.6% | 14 | 58.3% | |

|

Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m²) 5(m/f: 47%M, 53%F) |

no | 23 | 63.9% | 35 | 81.4% | 27 | 77.1% | 19 | 54.3% | 23 | 65.7% | 19 | 79.2% |

| yes | 13 | 36.1% 5 |

8 | 18.6% 5 |

8 | 22.9% 5 |

16 | 45.7% 5 |

12 | 34.3% 5 |

5 | 20.8% 5 |

|

|

HTN 5(Mf: 55%M; 45.4F) |

no | 34 | 94.4% | 25 | 58.1% | 2 | 5.7% | 31 | 88.6% | 19 | 54.3% | 0 | 0.0% |

| yes | 2 | 5.6% | 18 | 41.9% | 33 | 94.3% | 4 | 11.4% | 16 | 45.7% | 24 | 100% | |

|

DM 5(m/f: 54%M; 46%F) |

no | 30 | 83.3% | 13 | 30.2% | 7 | 20.0% | 29 | 82.9% | 9 | 25.7% | 1 | 4.2% |

| yes | 6 | 16.7% | 30 | 69.8% | 28 | 80.0% | 6 | 17.1% | 26 | 74.3% | 23 | 95.8% | |

|

Heart disease 5(m/f: 75%M; 25%F) |

no | 36 | 100% | 42 | 97.7% | 18 | 51.4% | 35 | 100% | 34 | 97.1% | 13 | 54.2% |

| yes | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.3% | 17 | 48.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 11 | 45.8% | |

|

kidney disease 5(m/f: 71.4%M; 29%F) |

no | 36 | 100% | 43 | 100% | 26 | 74.3% | 35 | 100% | 35 | 100.0% | 21 | 87.5% |

| yes | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 25.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 12.5% | |

|

Liver disease 5(m/f: 60%M; 40%F) |

no | 36 | 100% | 43 | 100.0% | 30 | 85.7% | 35 | 100.% | 35 | 100.0% | 22 | 91.7% |

| yes | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 5 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 8.3% | |

| other diseases | no | 35 | 97.2% | 38 | 88.4% | 30 | 85.7% | 27 | 77.1% | 17 | 48.6% | 10 | 41.7% |

| yes | 1 | 2.8% | 5 | 11.6% | 5 | 14.3% | 8 | 22.9% | 18 | 51.4% | 14 | 58.3% | |

| Smoking (94%M) | no | 14 | 38.9% | 29 | 67.4% | 34 | 97.1% | 35 | 100% | 34 | 97.1% | 24 | 100.0% |

| yes | 22 | 61.1% | 14 | 32.6% | 1 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% | |

|

Stool Ag test 5(31.25%; 65/208) 5(mf: 49%; 51%F) |

negative | 24 | 66.7% | 34 | 79.1% | 24 | 68.6% | 23 | 65.7% | 20 | 57.1% | 18 | 75.0% |

| positive | 12 | 33.3% | 9 | 20.9% | 11 | 31.4% | 12 | 34.3% | 15 | 42.9% 5 |

6 | 25.0% | |

| Gender-Specific Associationto Chronic Diseases | Risk of H.pyloriInfection and Association in Chronic Diseases | ||||||

| Odd’s Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | pValue | Odd’s Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | pValue | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.491 | (1.006 | 2.209) | 0.041 | 1.648 | .900 3.017 | .052 |

| Obesity | 1.586 | .872 | 2.882 | .036 | 19.217 | 9.117 40.507 | .000 |

| Hypertension | 1.103 | .586 | 1.751 | .002 | .676 | .373 1.225 | 1.672 |

| DM | 1.102 | .634 | 1.914 | .118 | .819 | .454 1.479 | .437 |

| Kidney diseases | .385 | 0.101 | 1.464 | 2.096 | 1.619 | .494 5.307 | .643 |

| Liver diseases | .474 | .090 | 2.500 | .808 | 3.060 | .665 14.088 | 2.260 |

| Heart diseases | 0.780 | 0.355 | 1.716 | 0.382 | 1.118 | .491 2.546 | .071 |

| Smoking | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.167 | 0.000 | |||

| Other diseases | 1.277 | .654 2.490 | .514a | ||||

| Obesity | Stool Ag test | Total | ||

| negative | positive | |||

| no | Count | 127 | 19 | 146 |

| % within stool Ag test | 88.8% | 29.2% | 70.2% | |

| yes | Count | 16 | 46 | 62 |

| % within stool Ag test | 11.2% | 70.8% | 29.8% | |

| Chi-Square Tests | Value | Asymp. Sig. (2-sided) | Exact Sig. (2-sided) | Exact Sig. (1-sided) |

| Pearson Chi-Square | 75.819a | .000 | ||

| Continuity Correctionb | 72.998 | .000 | ||

| Likelihood Ratio | 74.664 | .000 | ||

| Fisher's Exact Test | .000 | .000 | ||

| Linear-by-Linear Association | 75.454 | .000 | ||

| N of Valid Cases | 208 |

| Risk Estimate | Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Odds Ratio for Obesity (no / yes) | 19.217 | 9.117 | 40.507 |

| For cohort stool Ag test = negative | 3.371 | 2.200 | 5.165 |

| For cohort stool Ag test = positive | .175 | .112 | .274 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).