Submitted:

02 August 2023

Posted:

04 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

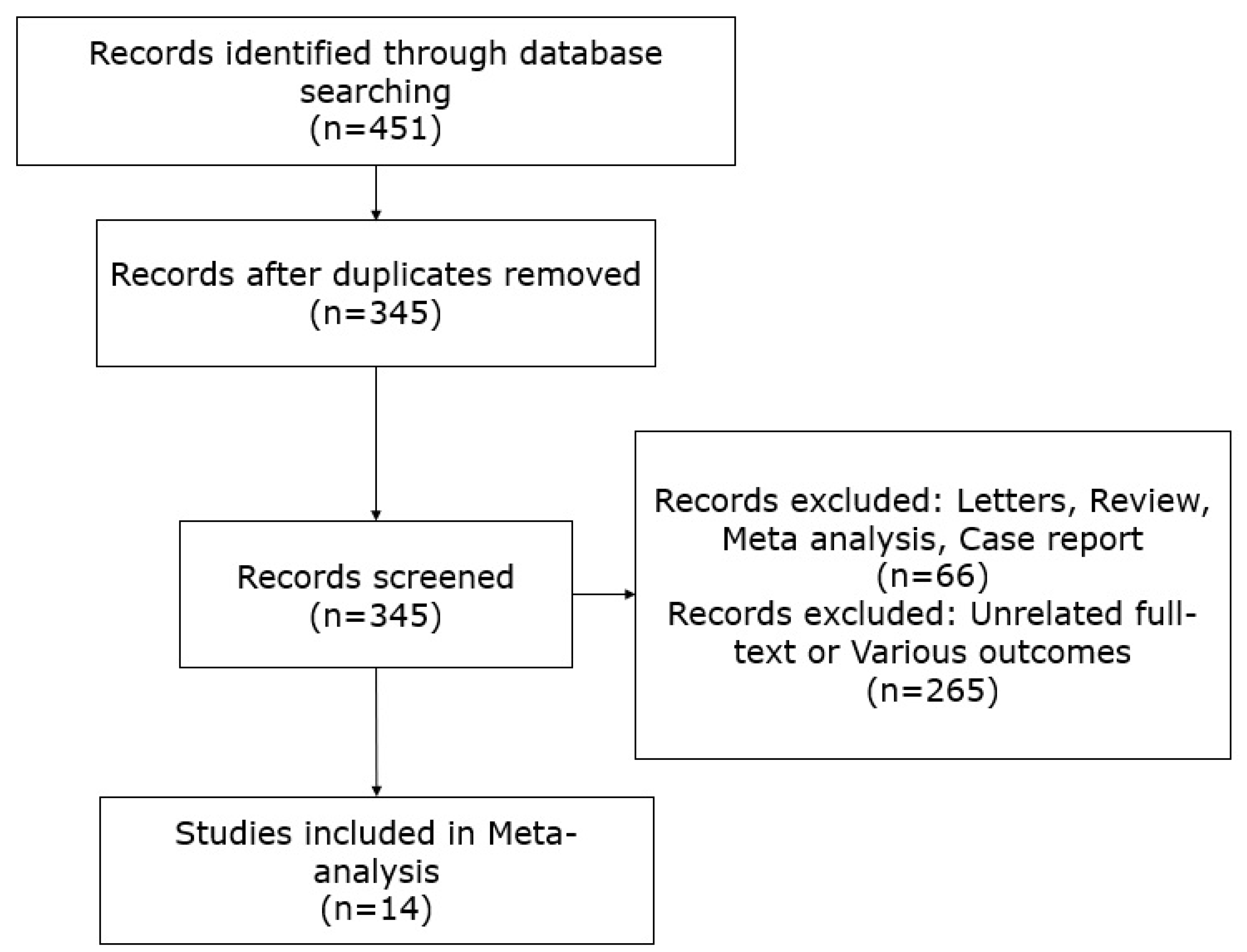

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

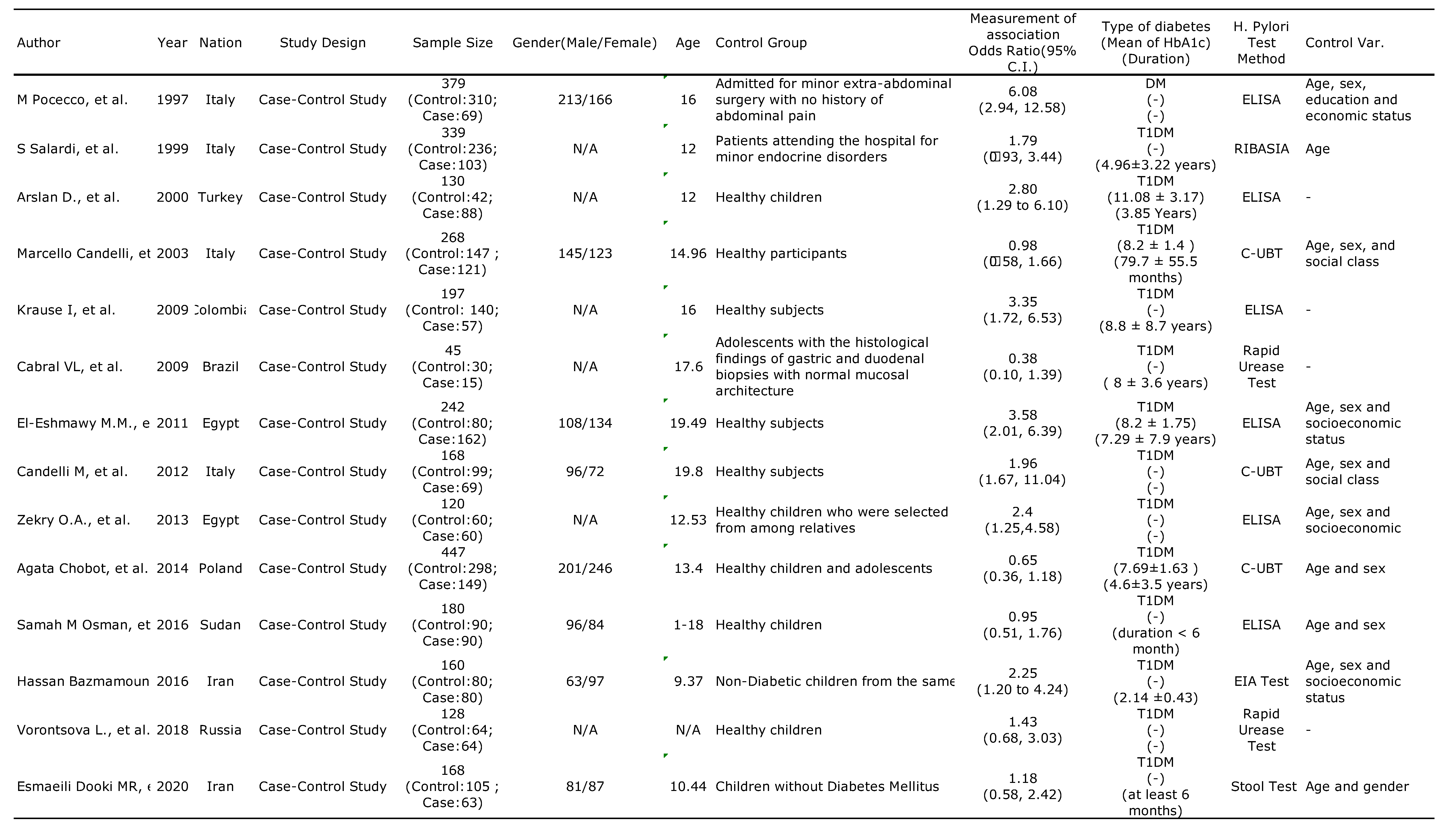

3.1. Characteristics and Methodologies of the Included Studies

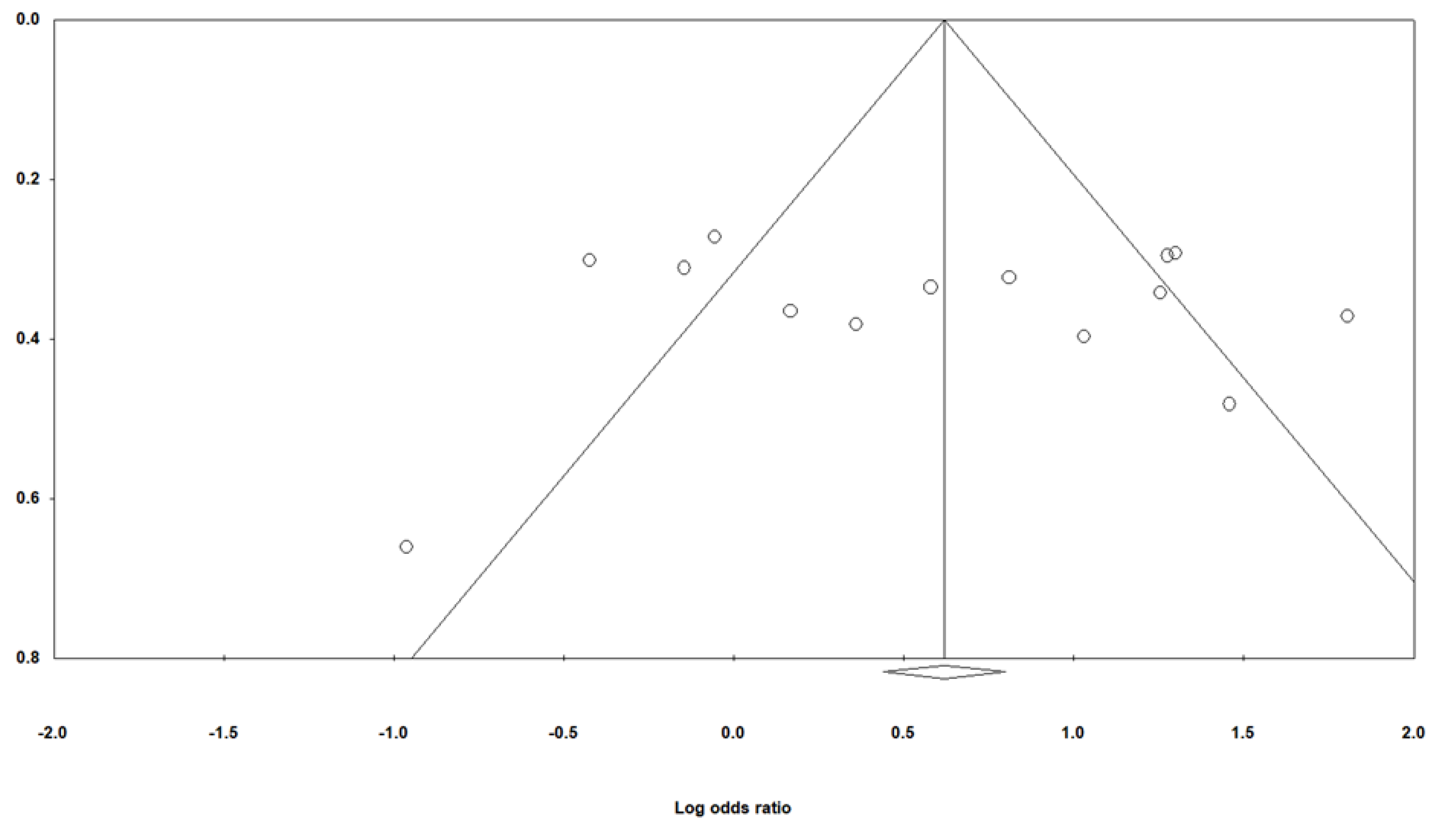

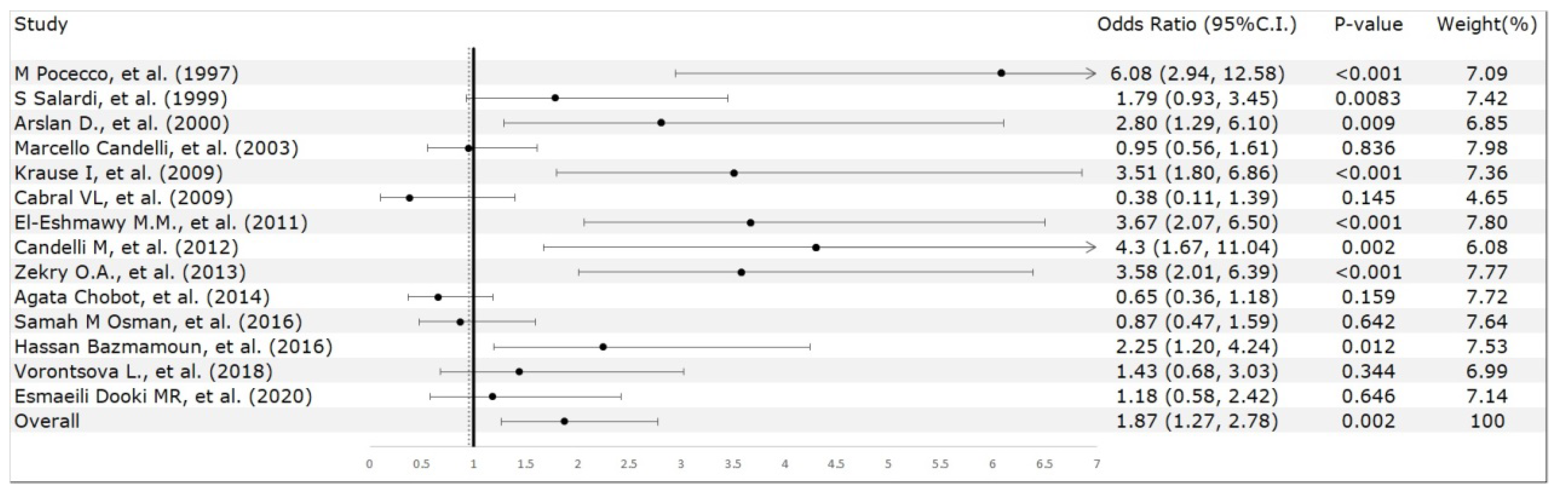

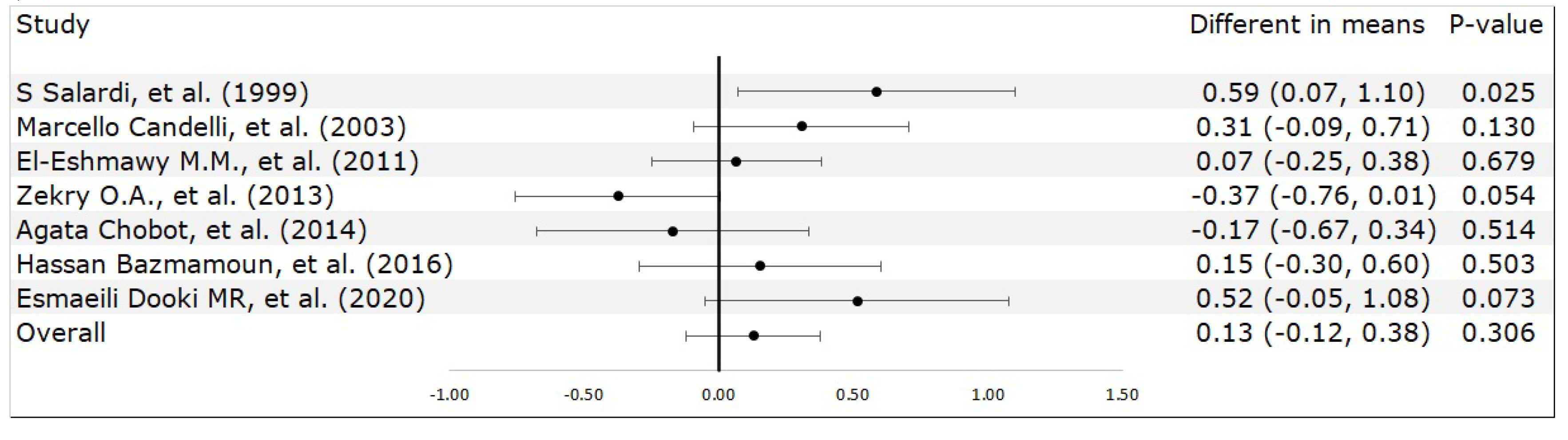

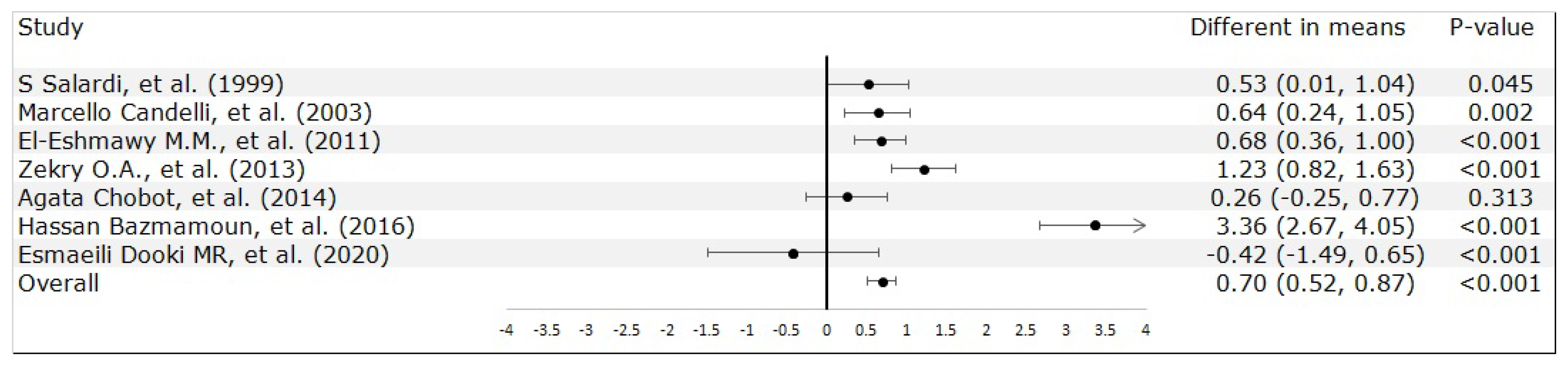

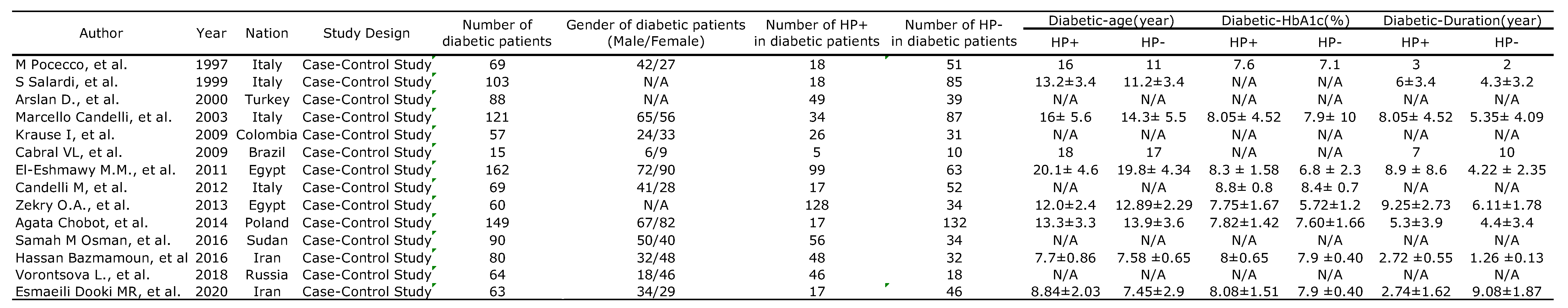

3.2. Meta-Analysis Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buzzetti, R.; Zampetti, S.; Maddaloni, E. Adult-onset autoimmune diabetes: current knowledge and implications for management. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2017, 13, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harjutsalo, V.; Sjöberg, L.; Tuomilehto, J. Time trends in the incidence of type 1 diabetes in Finnish children: a cohort study. Lancet 2008, 371, 1777–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvonen, M.; Viik-Kajander, M.; Moltchanova, E.; Libman, I.; LaPorte, R.; Tuomilehto, J. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (DiaMond) Project Group. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes mondiale (DiaMond) project Group. Diabetes care 2000, 23, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songini, M.; Mannu, C.; Targhetta, C.; Bruno, G. Type 1 diabetes in Sardinia: facts and hypotheses in the context of worldwide epidemiological data. Acta diabetologica 2017, 54, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ferranti, S.D.; de Boer, I.H.; Fonseca, V.; Fox, C.S.; Golden, S.H.; Lavie, C.J.; Magge, S.N.; Marx, N.; McGuire, D.K.; Orchard, T.J.; et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Circulation 2014, 130, 1110–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Michels, A.W. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2014, 383, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McColl, K.E. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. The New England journal of medicine 2010, 362, 1597–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoder, G.; Muhammad, J.S.; Mahmoud, I.; Soliman, S.S.M.; Burucoa, C. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and its associated factors among healthy asymptomatic residents in the United Arab Emirates. Pathogens 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burucoa, C.; Axon, A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, F.; Rayner-Hartley, E.; Byrne, M.F. Extraintestinal manifestations of Helicobacter pylori: a concise review. World journal of gastroenterology 2014, 20, 11950–11961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Zavos, C.; Deretzi, G. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and insulin resistance: a systematic review. Helicobacter 2011, 16, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaira, U.; Gatta, L.; Ricci, C.; D’Anna, L.; Iglioli, M.M. Helicobacter pylori: diseases, tests and treatment. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver 2001, 33, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouitcheu Mabeku, L.B.; Noundjeu Ngamga, M.L.; Leundji, H. Helicobacter pylori infection, a risk factor for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a hospital-based cross-sectional study among dyspeptic patients in Douala-Cameroon. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansori, K.; Moradi, Y.; Naderpour, S.; Rashti, R.; Moghaddam, A.B.; Saed, L.; Mohammadi, H. Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. BMC gastroenterology 2020, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M.C.; Wang, S.S.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Kuo, F.C.; Soon, M.S.; Wu, D.C. Helicobacter pylori infection associated with high HbA1c and type 2 diabetes. European journal of clinical investigation 2013, 43, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, N.; Lim, S.H.; Noh, G.; Kim, K.W.; Park, J.; Jo, H.; Yoon, H.; Shin, C.M.; et al. Long-term effect of the eradication of Helicobacter pylori on the hemoglobin A1c in type 2 diabetes or prediabetes patients. The Korean journal of internal medicine 2022, 37, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Xing, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ma, H. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and glycated hemoglobin A in diabetes: A meta-analysis. Journal of diabetes research 2019, 2019, 3705264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluf, S.; Salgado, J.V.; Cysne, D.N.; Camelo, D.M.F.; Nascimento, J.R.; Maluf, B.V.T.; Silva, L.D.M.; Belfort, M.R.C.; Silva, L.A.; Guerra, R.N.M.; et al. Increased glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection are associated with the grading of chronic gastritis. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luis, D.A.; de la Calle, H.; Roy, G.; de Argila, C.M.; Valdezate, S.; Canton, R.; Boixeda, D. Helicobacter pylori infection and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes research and clinical practice 1998, 39, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Higgins, J.P. Meta-analysis and subgroups. Prevention science: the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research 2013, 14, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Eshmawy, M.M.; El-Hawary, A.K.; Abdel Gawad, S.S.; El-Baiomy, A.A. Helicobacter pylori infection might be responsible for the interconnection between type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis. Diabetology and metabolic syndrome 2011, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zekry, O.A.; Abd Elwahid, H.A. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and autoimmune thyroiditis. The journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association 2013, 88, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salardi, S.; Cacciari, E.; Menegatti, M.; Landi, F.; Mazzanti, L.; Stella, F.A.; Pirazzoli, P.; Vaira, D. Helicobacter pylori and type 1 diabetes mellitus in children. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 1999, 28, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toporowska-Kowalska, E.; Wasowska-Królikowska, K.; Szadkowska, A.; Bodalski, J. [Helicobacter pylori infection and its metabolic consequences in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus]. Medycyna wieku rozwojowego 2007, 11, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Candelli, M.; Rigante, D.; Marietti, G.; Nista, E.C.; Crea, F.; Bartolozzi, F.; Schiavino, A.; Pignataro, G.; Silveri, N.G.; Gasbarrini, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Helicobacter pylori, gastrointestinal symptoms, and metabolic control in young type 1 diabetes mellitus patients. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree, J.E. Role of cytokines in pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced mucosal damage. Digestive diseases and sciences 1998, 43, 46S–55S. [Google Scholar]

- Perdichizzi, G.; Bottari, M.; Pallio, S.; Fera, M.T.; Carbone, M.; Barresi, G. Gastric infection by Helicobacter pylori and antral gastritis in hyperglycemic obese and in diabetic subjects. The new microbiologica 1996, 19, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Lv, Z. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with diabetes mellitus and diabetic nephropathy: a meta-analysis of 39 studies involving more than 20,000 participants. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases 2013, 45, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili Dooki, M.R.; Alijanpour Aghamaleki, M.; Noushiravani, N.; Hosseini, S.R.; Moslemi, L.; Hajiahmadi, M.; Pournasrollah, M. Helicobacter pylori infection and type 1 diabetes mellitus in children. Journal of diabetes and metabolic disorders 2020, 19, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk, O.; Canturk, Z.; Cetinarslan, B.; Ercin, C.; Hulagu, S.; Canturk, N.Z. Prevalence and comparisons of five different diagnostic methods for Helicobacter pylori in diabetic patients. Endocrine research 2001, 27, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, J.C.; Day, C.; Bailey, C.J.; Samuel, A.; Chusney, G.D.; Garland, H.O.; Hamilton, K.; Balment, R.J. Plasma sialic acid in animal models of diabetes mellitus: evidence for modulation of sialic acid concentrations by insulin deficiency. Life sciences 1995, 57, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkonen, K.H.; Ringner, M.; Ljungh, A.; Wadström, T. High-affinity binding of laminin by Helicobacter pylori: evidence for a lectin-like interaction. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology 1993, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, A.D.; Manson, J.E.; Rifai, N.; Buring, J.E.; Ridker, P.M. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2001, 286, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bener, A.; Micallef, R.; Afifi, M.; Derbala, M.; Al-Mulla, H.M.; Usmani, M.A. Association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Helicobacter pylori infection. The Turkish journal of gastroenterology: the official journal of Turkish Society of Gastroenterology 2007, 18, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manco, M.; Putignani, L.; Bottazzo, G.F. Gut microbiota, lipopolysaccharides, and innate immunity in the pathogenesis of obesity and cardiovascular risk. Endocrine reviews 2010, 31, 817–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, S.; Ma, Y.; Jin, C.; Lv, J.; Tong, M.; Wang, B.; Li, L.; Ning, Y. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and diabetes: A cross-sectional study in China. Journal of diabetes research 2020, 2020, 7201379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, M.; Lin, Y.; Kikuchi, S. Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2019, 1149, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).