This theoretical study focuses on the advanced development of kinematic and dynamic principles in analytical mechanics, specifically concerning higher-order acceleration energies and their applications in complex mechanical systems.

The approach is based on rigorous mathematical models and matrix formulations to extend existing theories. This section outlines the theoretical framework, mathematical tools, and key equations employed in formulating higher-order dynamics for rigid and multibody systems, providing the foundation for the later analysis of dynamic behaviors under complex motion conditions.

2.1. Position and Orientation Parameters of Solid Body

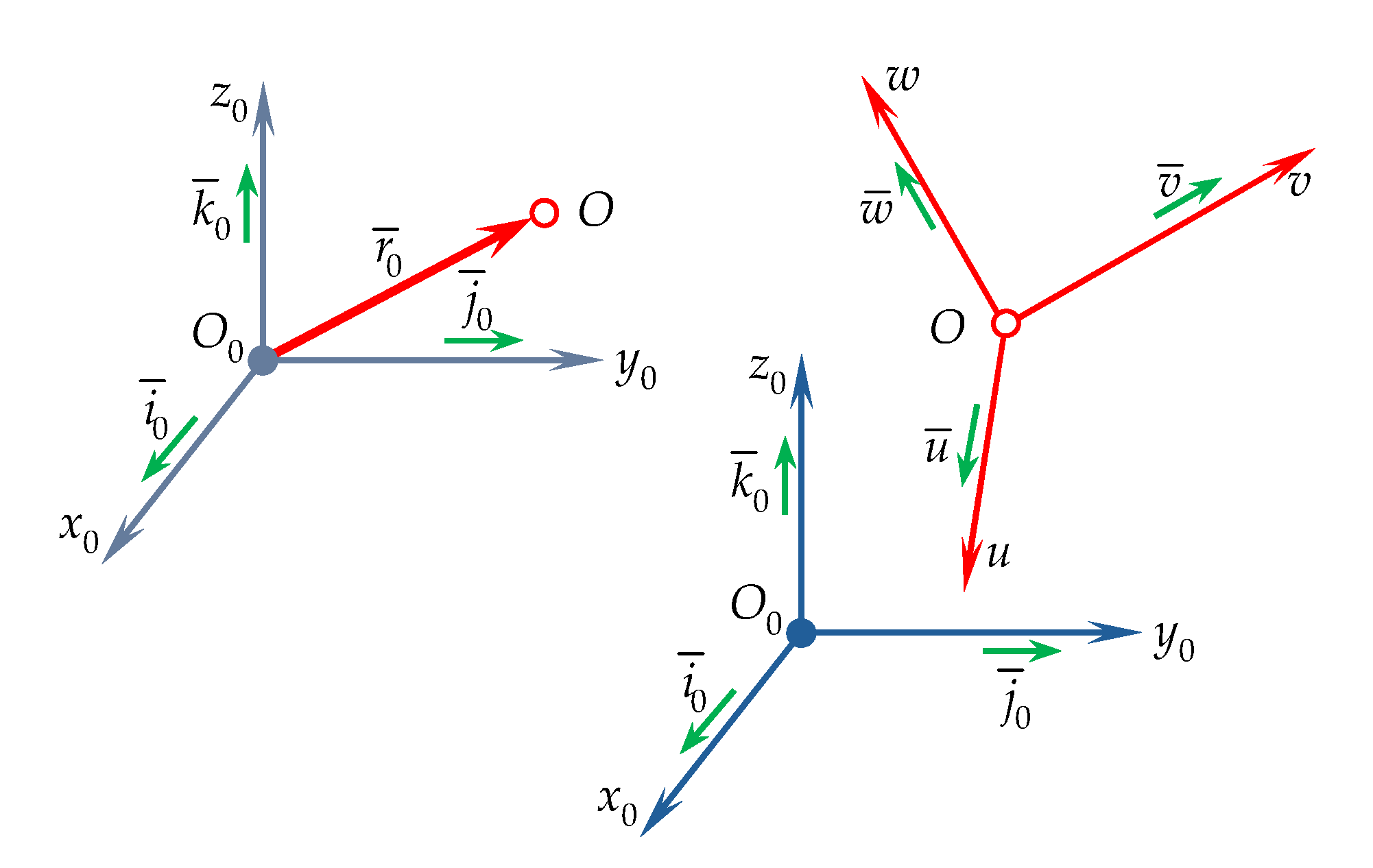

The solid body is a physical form of matter’s existence in the material universe. Consequently, the solid body is considered a material continuum. Based on this property to achieve an exact geometric solution, the solid body is decomposed into an infinite number of elementary particles, each with an infinitesimal mass and a continuous distribution throughout its geometric form. If the distances between the elementary particles are kept constant, the solid body will be characterized as a rigid solid (S). When density is consistently supported within the rigid structure, a homogeneous rigid solid is obtained. If the integration limits around the entire geometric contour are well-defined, the homogeneous body will have a simple or regular geometric shape. In this case, geometric and mass integrals are applied. Before conducting the mechanical study (static, kinematic, and dynamic modeling), it is essential to show the geometric state of the rigid body at each moment of its movement in Cartesian space. To this end, the geometric state of the simplest mechanical model, the material point, is studied first (

Figure 1). Based on research from [

4,

5,

6], the following notations are introduced:

In expression (1), the coordinates and axes of the Cartesian reference system are defined; in expression (2), the unit vectors (versors) of the reference system axes are specified, and in expression (3), the angles and direction cosines are defined.

Following

Figure 1, the rigid body is subject to geometric study. For this purpose, two reference systems are considered: the first system, denoted as

, is a fixed reference system, and the second system,

, is a moving reference system, permanently attached to the body, with its origin at point

, an arbitrary point on the rigid body. The reference system

, also represented in the

Figure 1, is a system with its origin at point

, whose orientation remains constant throughout the motion and is identical to that of the fixed reference system,

, meaning

. The geometric state of any point belonging to the rigid body (for example, an arbitrary point

) represents its

position, defined, according to

Figure 1, by the following position vector:

For a free material point, the three linear coordinates defined in (5) are independent and represent the degrees of freedom (d.o.f.). The study then extends to a vector or an axis belonging to the Cartesian reference system (

Figure 1).

This geometric state is referred to as

orientation (angular state). Orientation (angular state) is defined by using unit vectors. For any unit vector

, assumed to be known in relation to one of the reference systems

or

, the orientation will be defined by means of the direction cosines.

In accordance with linear algebra, the symbol

in expression (6) defines the transpose of the matrix. Considering the second expression in (6), it can be observed that the orientation of any vector or axis is defined by two independent angles. The geometric aspects presented earlier are examined in the context of an orthogonal, right-handed reference system (see

Figure 1,

) relative to the fixed reference system

. In this case, the geometric state is represented by position and orientation. Position is defined by expression (5), while orientation is defined by the rotation matrix [

4,

6,

7]:

The resulting rotation matrix defined by (7) contains the unit vectors of the reference system

relative to the fixed reference system

. The rotation matrix, or direction cosine matrix, describes the orientation of each axis of the moving reference system attached to the rigid body in relation to a fixed reference system. Among the nine direction cosines in the rotation matrix, six mathematical relationships can be proved. Therefore, the orientation of a moving reference system relative to a fixed reference system can be defined by a maximum of three independent parameters, represented by the orientation angles. Consequently, the resulting orientation of a reference system

relative to another reference system,

or

, can be defined by three independent orientation angles (degrees of freedom), according to [

4,

6]:

The angles included in (8) are components of the orientation column matrix

, which geometrically describe dihedral angles between two geometric planes:

Physically, the three angles defined by expression (9) represent a simple rotation around one of the three axes of the Cartesian reference system: .

Based on the research in [

4,

6], combining these three simple rotations results in 12 sets of orientation angles (8). Considering

, the expressions for the three simple rotation matrices are further developed as follows:

The following mathematical representation of the generalized rotation matrix is proposed:

where,

and,

By substituting (13) and (14) into the generalized expression (12), the simple rotation matrices defined in (11) are obtained. The generalized matrix can thus be written as follows:

In expression (15), the symbol

defines the antisymmetric matrix associated with vector (17), while

represents the diagonal matrix, determined as:

The matrix (15) can also be defined by means of the following classical formulation:

According to the research [

4,

5,

8], the three simple rotations defined by (8) can be performed either around the fixed axes or the moving axes, belonging to the

and

/

reference systems. The resulting rotation matrix, denoted

, which expresses the orientation of the

reference system relative to

fixed reference system, is defined by expressions that also include matrix exponentials, as follows:

Using the author’s research on matrix exponentials [

5,

9,

10], the resulting rotation matrix can be expressed in a new form as follows:

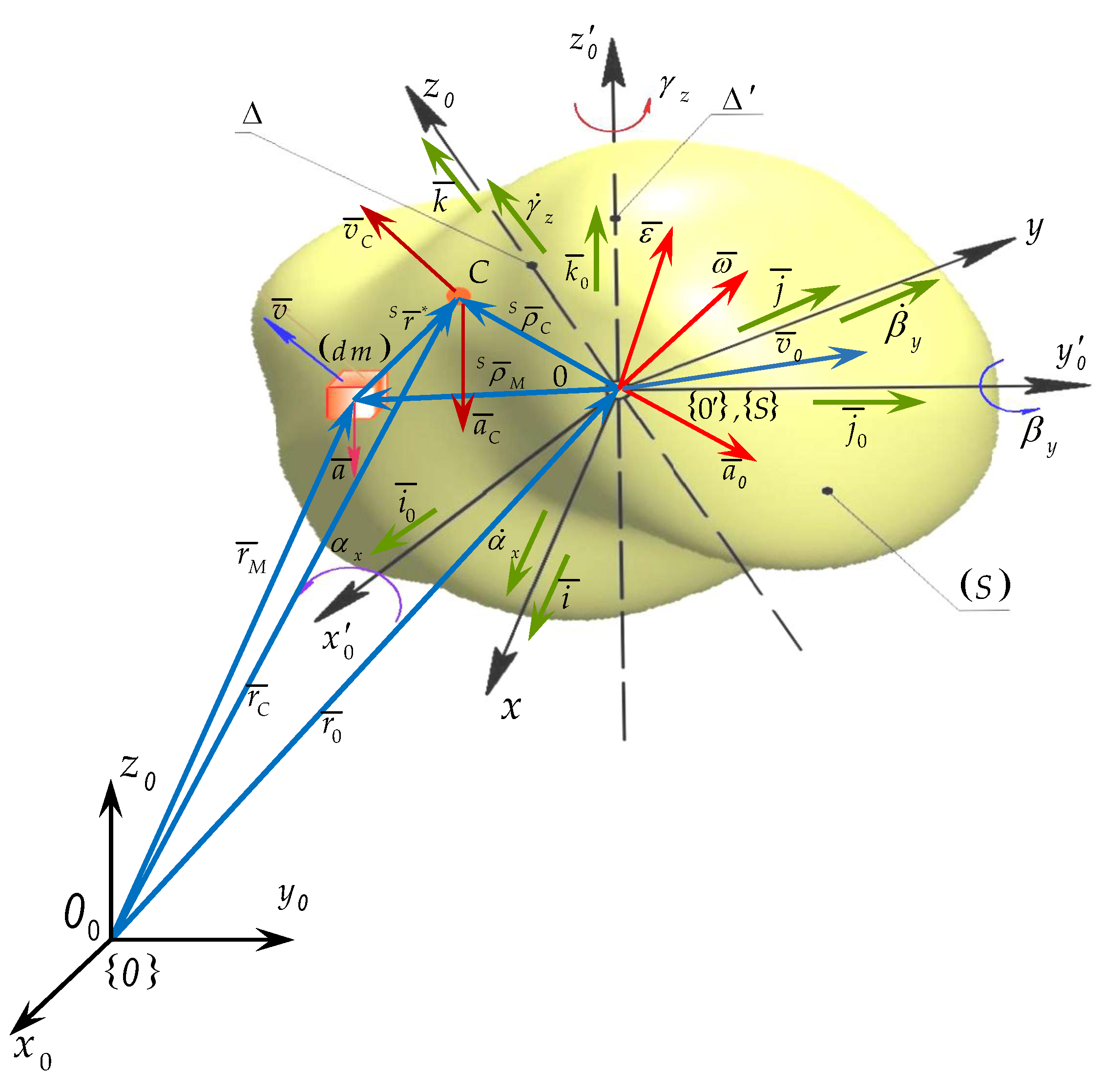

Expressions (5) and (8), presented above, define the position and orientation of a right-handed reference system. These mathematical expressions will be generalized for the case of a rigid body. According to [

5,

6], a rigid body is composed of an infinite number of material particles and an infinite number of geometric axes, parallel and perpendicular to each other, characterized by a continuous distribution throughout the entire volume of the rigid body [

5,

8]. The rigid body also includes an infinite number of sets consisting of three orthogonal geometric planes, continuously distributed throughout its volume. Geometrically, to define a right-handed reference system with its origin at an arbitrary point

belonging to the rigid body, it is sufficient to select a single set composed of three orthogonal planes. According to expression (4) and

Figure 2, this reference system is denoted

. The reference system

is attached to the rigid body. Expressions (5) and (8) define the position and orientation of this system.

Since the purpose of this paper is to study advanced dynamics, two material points belonging to the rigid body are considered, satisfying the conditions

and

. The expressions defining the absolute position become time-dependent vector functions [

4,

11], as follows:

Considering expressions (23) and (25), the absolute position equation can be written using matrix exponentials [

6,

9,

10], as follows:

The absolute position equation for any material point belonging to the rigid body can be determined when the position

and the orientation

of the moving system

are known. Analyzing expressions (23) and (24) reveals that the orientation is invariant for all points of the rigid body. Based on these geometric considerations, the body is represented by the reference system

. This system is geometrically defined by six independent parameters or degrees of freedom, included in the symbol:

where

and

is the generalized coordinate,

is an operator that highlights the type of degrees of freedom:

The symbols presented in expression (28) define higher-order generalized variables in the case of rapid motions, where is the order of the time derivative.

In advanced mechanics, instead of expression (8), the following definition is used for the angular orientation vector:

where

is the angular transfer matrix, which is a

matrix defined as a function of the orientation angles, and specified according to the expression below:

The position and orientation of the

moving reference system, relative to any other system, such as the

fixed reference system can be represented in matrix form using transformations based on matrix exponentials:

Expression (32) defines the position vector of the moving system relative to the fixed system , while (34) represents a vector defined as a function of screw parameters (homogeneous coordinates).

The conclusion and defining expressions presented in this introductory section will be applied further in the study of advanced kinematics and dynamics of mechanical systems.

2.2. The Parameters of Advanced Mechanics

Based on the authors’ research, this chapter will present a series of new formulations about advanced kinematic concepts. A rigid body (S) represented in

Figure 2 and undergoing general motion is considered. By applying the first-order absolute derivative to the parametric motion equations, we obtain:

According to [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], the antisymmetric matrix associated to angular vector is:

Finally, expressions for linear velocities and accelerations are obtained in the form:

The absolute position equation, expressed in terms of matrix exponentials results:

In advanced kinematics and dynamics, the higher-order derivatives applied to position vectors and rotation matrices are expressed as follows:

The defining expressions for angular velocities and accelerations can be proved based on matrix exponentials, as follows:

Although the use of matrix exponentials may appear complex, it offers advantages, including the elimination of reference systems, which can impose certain restrictions.

This is evident in the previously presented equations by

, showing that the unit vectors correspond to the initial state of the reference system

. The position of the center of mass is found relative to the reference system

, as:

The position of the mass center relative to

reference system at first, in classical form and then in an exponential form, is presented:

If first and second-order derivatives with respect to time are applied to expression (44) the linear velocity and acceleration of the center of mass are ultimately obtained:

The absolute linear accelerations of higher orders, with respect to mass center, are:

In dynamic modeling, the following expression is applied:

Using the author’s research [

10,

11,

13] on time functions for position and orientation, the following differential properties have been developed in the study of advanced kinematics and dynamics of the rigid body, according to the expressions:

Based on (52) – (54), the expressions for a rigid body are obtained:

where

Expressions (55) and (57) refer to the higher-order linear velocities and accelerations corresponding to the center of mass.

The other expressions, (56) and (58), define the higher-order angular velocities and accelerations specific to the rigid body in general motion.

The above expressions are also extended to multibody systems.

In case of rapid movements, higher order operational and generalized accelerations develop within the mechanical structure (for example serial robot structures). Based on the research from [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], the following expressions are found:

where

represents the order of differentiation with respect to time, the symbol

is the column matrix of higher-order operational accelerations, and

is the column matrix of higher-order generalized accelerations, defined according to:

Based on the mathematical models presented in [

5], the Jacobian matrix can be found using matrix exponentials. Analyzing all input parameters in advanced kinematics reveals that they are functions of the generalized variables (59) - (60) and their time derivatives. Thus, following [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], these can be developed using polynomial interpolation functions.

This paper proposes the following higher-order polynomial functions:

On each trajectory segment

, the number of unknowns is

, and the meaning of the terms contained in (61) is as follows

Determining the unknowns in (63) requires, in accordance with [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], the application of geometric and kinematic constraints:

The results of the polynomial interpolation functions (61) will be substituted into the expressions defining the concepts of advanced kinematics and dynamics. Expressions for input data and higher-order parameters are essential in defining the concepts of advanced dynamics. In this work, these are represented by kinetic energy and higher-order acceleration energies. These concepts will be integrated into dynamic equations characterizing the rapid motions of bodies.