Introduction

Malignant neoplasms are among the leading causes of death worldwide. In individuals aged 45 to 64 years, cancers cause the majority of lethalities[

1]. In Europe, there were about 2.74 million new cases[

2] in 2022 and 1.1 million cancer-related deaths in 2021.[

3] The United States also faced a staggering 1.9 million new cancer diagnoses and over 600,000 cancer-related deaths.[

4,

5] In 2021, Hungary reported approximately 70,000 new cancer cases and 33,000 deaths attributed to cancer.[

6] A recent study projected for men a rise globally in the number of cancer cases from 10.3 million in 2022 to 19 million by 2050 (> 84% increase). Deaths are expected to increase from 5.4 million to 10.5 million (>93% increase), with a more than twofold rise (>117%) projected among men aged 65 and older.[

7]

Despite the dedicated efforts of scientists and the pharmaceutical industry to develop safer and more effective cancer treatments, the global impact remains limited. Between 2000 and 2016, the FDA approved 92 novel cancer drugs for 100 indications based on 127 clinical trials. However, these drugs’ median absolute survival benefit was only 2.4 months.[

8] This stark reality underscores the need for transformative advancements in cancer research and treatment. It prompts a critical reassessment of the current strategy, mainly the decades-long focus on identifying new mutations and targeting elements of signaling pathways. While this approach has dominated cancer research for over 40 years, its overall efficacy in overcoming the disease is now being questioned. The challenge of cancer remains profound, and a definitive solution is yet to be found.

Recently, two comprehensive review papers summarized the outcomes of three decades of research on deuterium (D) and deuterium-depleted water (DDW).[

9,

10] These studies—initiated by a pioneering research published in 1993 that first demonstrated the cell growth inhibiting effect of DDW and proved to be a significant milestone in exploring alternative cancer therapies[

11]—confirmed the anticancer effects of deuterium depletion through multiple independent experiments, elucidating the underlying mechanisms and introducing a novel concept and target for cancer drug development. It has been demonstrated that replacing regular water (of 16 mmol/L D concentration, equivalent to 150 ppm, as found in natural waters) with deuterium-depleted water (3.2 mmol/L D concentration, equivalent to 30 ppm) inhibits cell growth

in vitro and leads to complete tumor regression

in vivo. Conversely, research has also shown that deuterium-enriched water, containing deuterium in 2-4-fold concentrations above natural levels (300–600 ppm), stimulated cell growth.

These findings, combined with earlier results[12-14] indicating a correlation between increased intracellular pH and cell division, suggest a critical role for the Na⁺/H⁺ exchanger in this process. It was supposed that the exchanger, sitting in the cell membrane and activated when a growth hormone binds to its receptors, preferentially transfers the lighter hydrogen isotope (protium), leading to an increased intracellular deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratio. Yeast ATPase was shown to prefer only hydrogen (not deuterium) as a substrate in proton transfer[

15] and in fibroblasts expressing yeast ATPase in their membrane, tumorigenicity, and increased intracellular pH was observed.[

14] This D/H ratio is proposed to act as a key sub-molecular signal for initiating cell growth which is supported by the data that deuterium-enriched media stimulated cell growth.11 Since Warburg’s discovery[

16] it has been well established that a hallmark of most cancer cells is their reliance on anaerobic metabolism, even in the presence of oxygen.[

16,

17] It has been hypothesized that properly functioning mitochondria in healthy cells produce deuterium-depleted metabolic water, which inhibits cell growth by counteracting the increase of the D/H ratio caused by activation of the Na⁺/H⁺ exchanger. When food is metabolized into water and carbon dioxide, the resulting metabolic water is deuterium-depleted, with a degree of depletion depending on the composition of the food. This hypothesis is supported by the dissimilar D concentrations of macronutrients: in proteins 135 ppm, slightly reduced vs. natural waters, significantly reduced, 109 to 118 ppm, in lipids; but about 150 ppm in carbohydrates.[

18] This metabolic water thus helps maintain a lower D/H ratio, acting as a regulatory mechanism to reduce the likelihood of reaching the threshold D/H ratio required to trigger cell growth. Supporting this hypothesis, recent experiments demonstrated that feeding tumor-bearing mice with deuterium-depleted yolk[

18] but with normal water extended their survival, underlining the critical role of mitochondrial activity in controlling the D/H ratio and inhibiting tumor progression. Consequently, in line with Warburg’s idea cancer cells’ uncontrolled growth characteristic likely arises from the inability of their mitochondria to generate deuterium-depleted metabolic water as a consequence of a defunct tricarboxylic acid cycle.[

16]

Evidence on the anticancer potential of deuterium depletion in humans has been obtained in a prospective phase 2 clinical trial involving prostate cancer patients[

19] and retrospective studies on lung[

20], breast cancer[

21], and glioblastoma.[

22] These studies, conducted on well-defined and homogeneous cancer populations in terms of cancer type and stage, revealed that when patients consumed DDW alongside conventional therapy, MST, depending on cancer type, increased three- to seven-fold compared to the historical control. These findings underscore the therapeutic promise of deuterium depletion, positioning it as a groundbreaking mechanism and a promising direction for future cancer research and treatment development.

Cancer drug registration requires conducting prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials. However, the small sample sizes in clinical trials often limit the reliability of the results and conclusions, as they may not accurately reflect the true efficacy and safety of the investigated drug candidates. To address this limitation, collecting and analyzing real-world data is essential for a comprehensive understanding of a drug’s performance, ultimately enabling a more accurate evaluation of its efficacy in cancer treatment.[

23]

Given DDW’s demonstrated safety[

19] and the absence of any dietary requirement for deuterium, drinking water with reduced deuterium content was introduced as a commercial food product in 1994 with approval from the Hungarian food safety organizations. This marked a significant step forward in making DDW accessible for broader use.

Patients consuming DDW voluntarily shared their experiences and outcomes before, during, and after DDW consumption, along with the results of follow-up oncology examination confirming the effectiveness of conventional treatments. This valuable feedback was collected by HYD LLC, and was processed in a comprehensive analysis across various tumor types, the published findings of which contributed to the growing body of evidence supporting DDW’s therapeutic potential.

In 32 years, reliable data have been collected on 2,649 patients (the first enrolled patient started to consume DDW in October 1992, and the last one, in October 2024), forming an ample set of real-world data, the foundation of the present publication. In this study, we focus on data of survival, the primary common descriptor of treatment outcome of any malignant disease.

Evaluation of the fate of cancer patients with and without DDW consumption required a reliable base of comparison. The 2023 Country Cancer Profile: Hungary report by the European Cancer Inequalities Registry was the foundation for conclusions that were subsequently compared with our data and findings. This comparison provided valuable context and insights into Hungary’s broader landscape of cancer care and outcomes.6

Methods

Patients

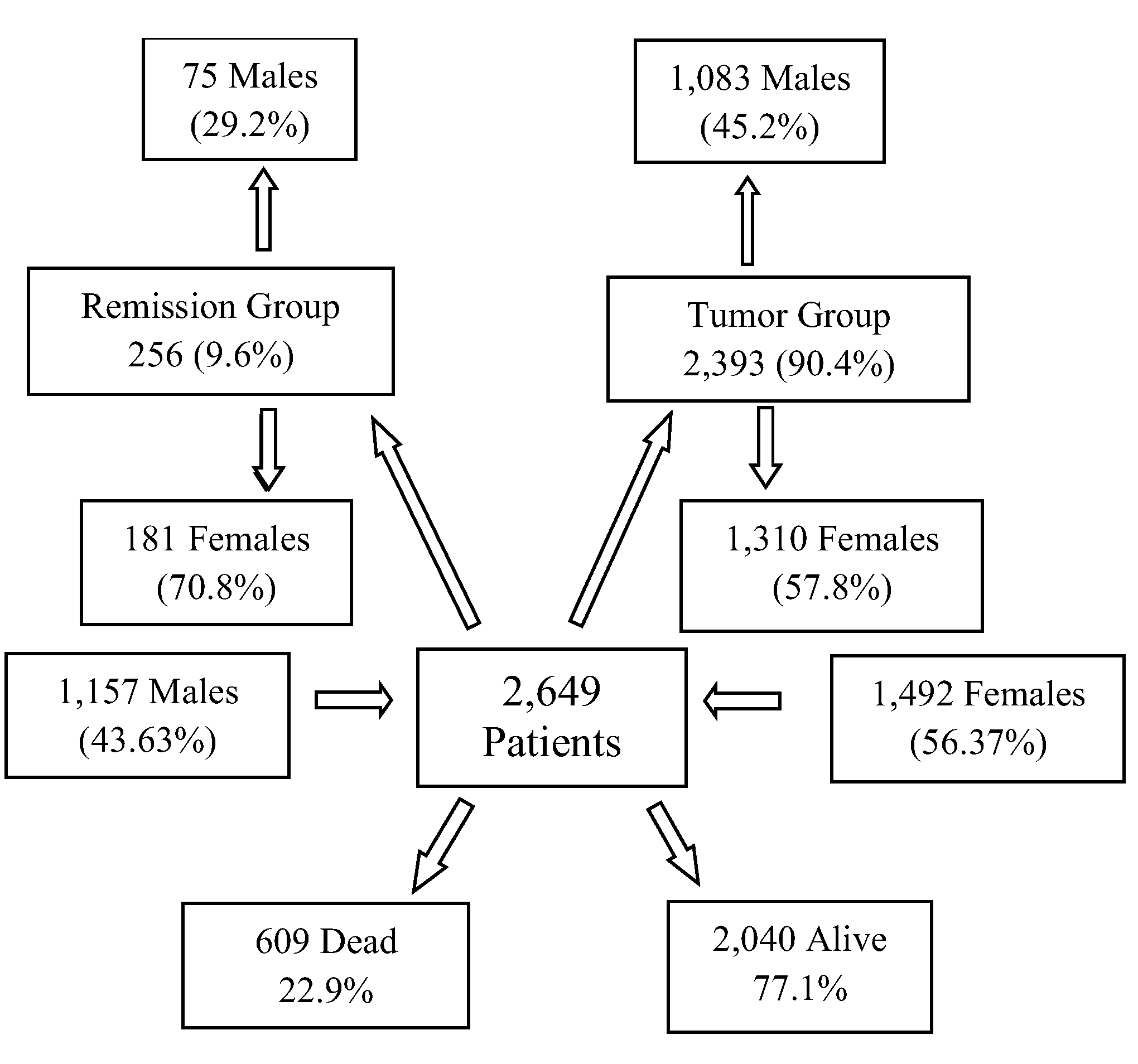

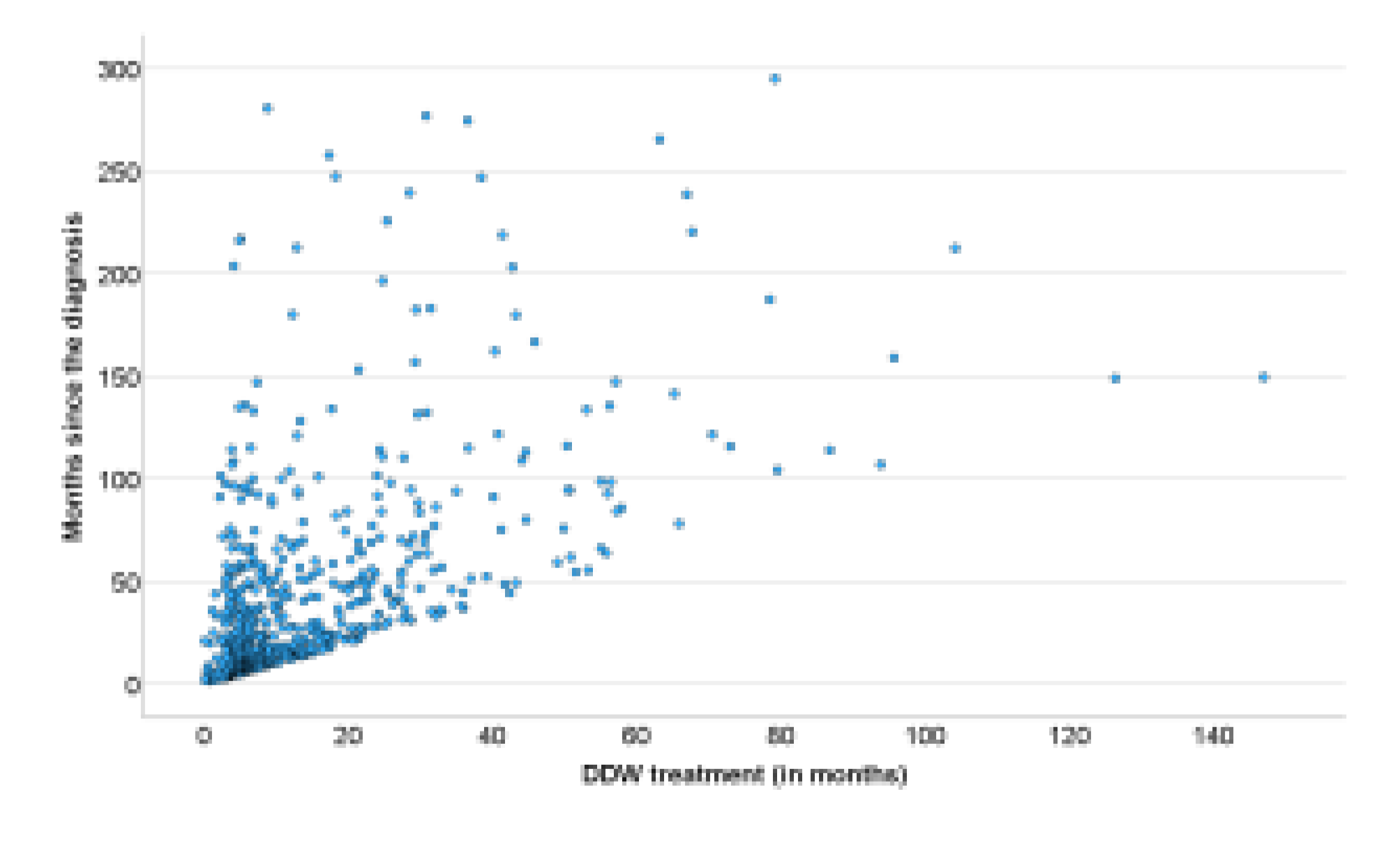

The evaluated cancer population encompasses a diverse range of malignancies, including various organs of origin, distinct pathological backgrounds, different stages, and diverse treatment protocols. The final database included 2,649 patients (

Figure 1), comprising 43.67% males (1,157) and 56.33% females (1,492). The average age of the overall population was 55.63 years (median: 58 years). Among males, the average age was 56.3 years (median: 60 years), while for females, it was 55.1 years (median: 56 years). The average body weight across the population was 69.6 kg (median: 70), with males averaging 76.1 kg (median: 76 kg) and females averaging 64.7 kg (median: 64 kg).

DDW Production and Its Application for Human Use

Deuterium-depleted water was produced from ordinary water containing the natural concentration of deuterium (150 ppm, equivalent to 16.8 mmol/L). Fractional distillation was employed to reduce the deuterium (D) concentration to 50–25 ppm. This method is based on the differences in the physical properties of normal water (H₂O) and heavy water (D₂O)—specifically, that, in equilibrium with liquid water, steam at the boiling point of normal water contains approximately 2.5% less deuterium. The deuterium content of water was progressively reduced through repeated evaporation, which was performed on an industrial scale in distillation towers, and the distillate was measured. The instrument (Liquid-Water Isotope Analyzer-24d, manufactured by Los Gatos Research Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) uses off-axis integrated cavity output spectroscopy to measure the absolute abundances of D-containing water molecules via laser absorption. The deuterium concentration is given in ppm (with ±1ppm accuracy as stated by the manufacturer).

To prepare the final products (that is, the drinking waters Preventa 125, 105, 85, 65, 45, and 25), DDW was mixed with high-quality spring water to set the required D concentration and replenish minerals removed during distillation. For the latter purpose, a mineral stock solution was also used.

DDW is now commercially available under different brand names in several countries, including the United States of America, Russia, China, Japan, Romania, and Hungary. The production and sales of DDW have been steadily growing worldwide, reaching a yearly amount of approx. 600 tons by 2024.

To maximize the potential efficacy of DDW, patients are advised to consume it exclusively, at a rate of 1.5–2 liters per day, depending on an average body weight of 60–80 kg. For individuals weighing over 80 kg, daily DDW intake should exceed 2 liters. The quantity of DDW consumed should account for 75–80% of the total daily fluid intake, while the remaining 20–25% is expected to come from the water content in food. The optimal D concentration and the duration of consumption depend on various factors, including the type of cancer, its stage, and any ongoing conventional therapy. Generally, it is advisable to begin DDW consumption at either 105 ppm or 85 ppm, as these levels were found to be necessary for efficacy

21. The primary concept behind DDW administration is to achieve a gradual, sustained reduction in the body’s deuterium levels over time, thereby challenging the metabolism of all cancer and healthy cells. To facilitate this, the DDW being consumed should be progressively replaced with another one with 20 ppm lower D concentration than the previous level. The recommended duration for consuming DDW with a specific concentration is typically 2–3 months. However, this can vary depending on factors such as the type of conventional therapy, cancer localization, pathology, and the individual’s response to conventional treatment and DDW consumption.[

24]

Integration of DDW into Conventional Therapies

The use of DDW is not classified as a treatment. Our study was designed to collect data from cancer patients undergoing conventional therapies such as chemotherapy, targeted drug therapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, or surgery while consuming DDW. The oncologists’ treatment protocols remained untouched and no extra patient examinations were conducted. Instead, the information generated during the participating patients’ conventional therapies was provided voluntarily to HYD LLC, which collected and processed it and gave advice to DDW consumption based on the patients’ medical history and the results of follow-up examinations.

A set of detailed protocols was developed for patients suffering from various malignancies in different stages based on insights from over 30 years of follow-up studies. These are specified in the book Deuterium Depletion—A New Way in Curing Cancer and Preserving Health.24 Studies, including a landmark article on lung cancer, further support the value/usefulness of these protocols, underscoring the benefits of DDW consumption.20

Evaluation of Provided Data of the DDW-Consuming Cancer Patients

This population-based observational retrospective study evaluates the data accumulated over 32 years (the first patient was enrolled on October 29th, 1992, and the last one on October 18th, 2024). All patients enrolled in the study were diagnosed with cancer, and while receiving conventional therapy, they also consumed DDW in parallel, as stated above. As previously explained, DDW consumption was the only difference from the overall Hungarian cancer population used as the comparison base. The evaluated patient population was highly heterogeneous regarding tumor types, stages, conventional therapies received, and the duration of DDW consumption. Given this variability, the evaluation of survival data was chosen as the study’s primary endpoint; that is, the survival times of the DDW-consuming patients were compared to the historical control described in the next section to draw meaningful conclusions.

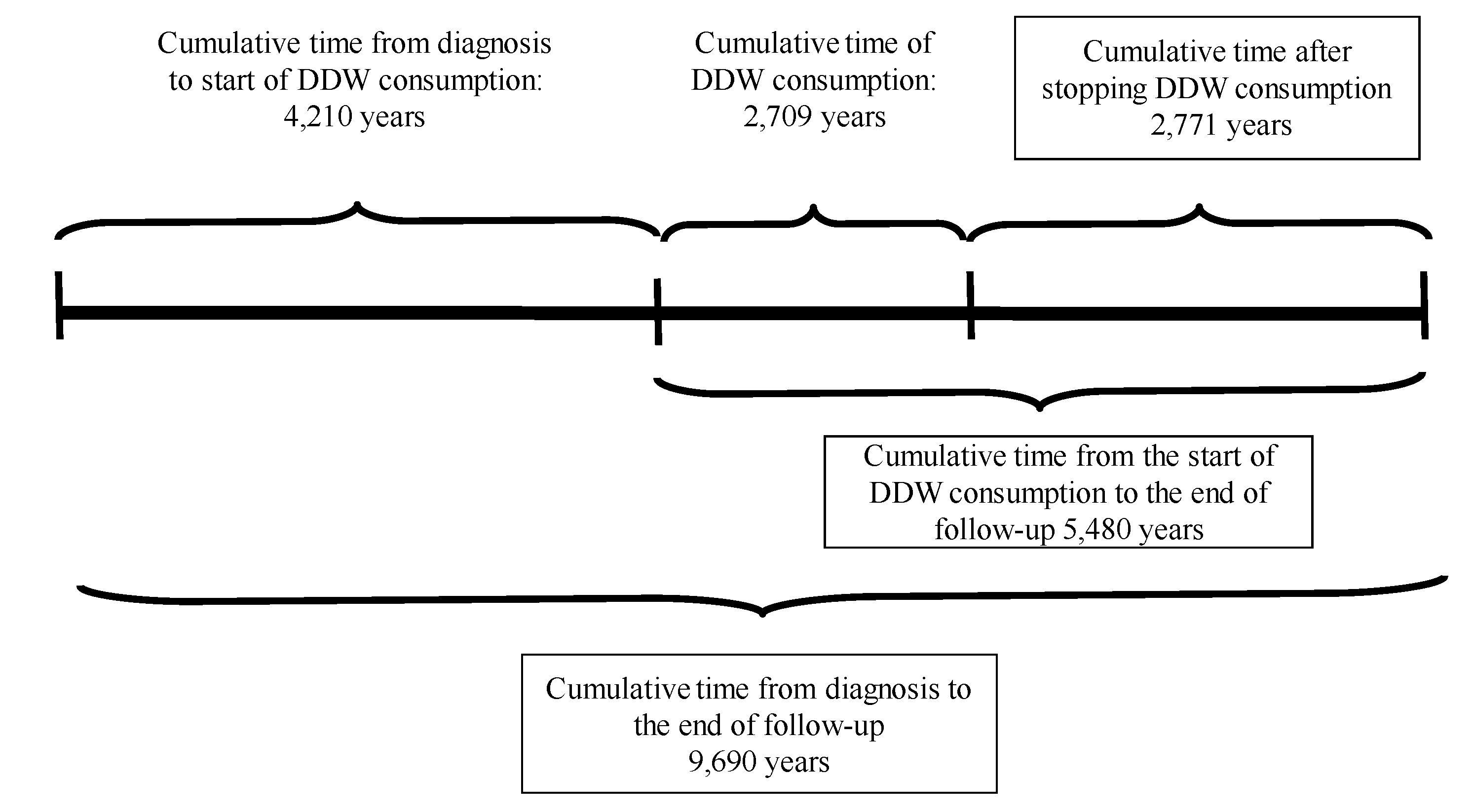

On the participants the following information was available: pseudonymization code, gender, age at the start of DDW consumption, body weight, primary cancer localization, date of diagnosis, date of DDW initiation, staging at the beginning of DDW consumption (remission or active tumor presence), date of DDW consumption ended, date of the last recorded information, and the patient’s status (alive or deceased) at that time. The medical history of patients with DDW consumption was divided, according to the above-mentioned data, into three primary phases, with two additional phases calculated from these (

Figure 2).

Time from Diagnosis to the Start of DDW Consumption: The period between the initial diagnosis and the beginning of DDW treatment.

Duration of DDW Consumption: The total time the patient consumed DDW.

Follow-Up Time After Stopping DDW Consumption: The duration from the cessation of DDW consumption to the end of the follow-up period.

Total Time from Diagnosis to the End of Follow-Up: The combined time spanning from diagnosis to the conclusion of follow-up.

Time from the Start of DDW Consumption to the End of Follow-Up: The interval from the initiation of DDW treatment to the end of the follow-up period.

Endpoints and Assessment

Given the heterogeneity of the enrolled population, survival was selected as the primary endpoint for assessing the efficacy of deuterium depletion. Earlier studies conducted on small, homogeneous cancer subpopulations demonstrated several key findings: prolonged DDW consumption correlated with extended survival, lower deuterium concentrations of DDW were associated with higher response rates, particularly in breast cancer patients[

21], and different tumor types exhibited varying degrees of sensitivity to deuterium depletion, as observed in lung cancer[

20,

25] and glioblastoma multiforme.[

22] These studies, importantly, also proved the validity of the available data and the analysis method. The current study will expand the evaluation to include the entire population, but to ensure robustness and validation, analyses will also focus on specific subgroups. This approach is expected to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between deuterium depletion and cancer progression/regression and to evaluate the potential of integrating deuterium depletion into conventional therapy.

Study Oversight

This study is a population-based observational retrospective analysis based on data collected over 32 years by HYD LLC. Patients consuming deuterium-depleted drinking water (marketed under the brand name Preventa®) already available on the market voluntarily shared their experiences and the results of their follow-up examinations. All patients received standard oncological treatments according to established protocols, and no intervention was made beyond monitoring their DDW consumption.

The data evaluation process involved collaboration with experienced statisticians and leading oncologists to ensure a thorough and validated analysis and interpretation of the results.

Statistical Analysis

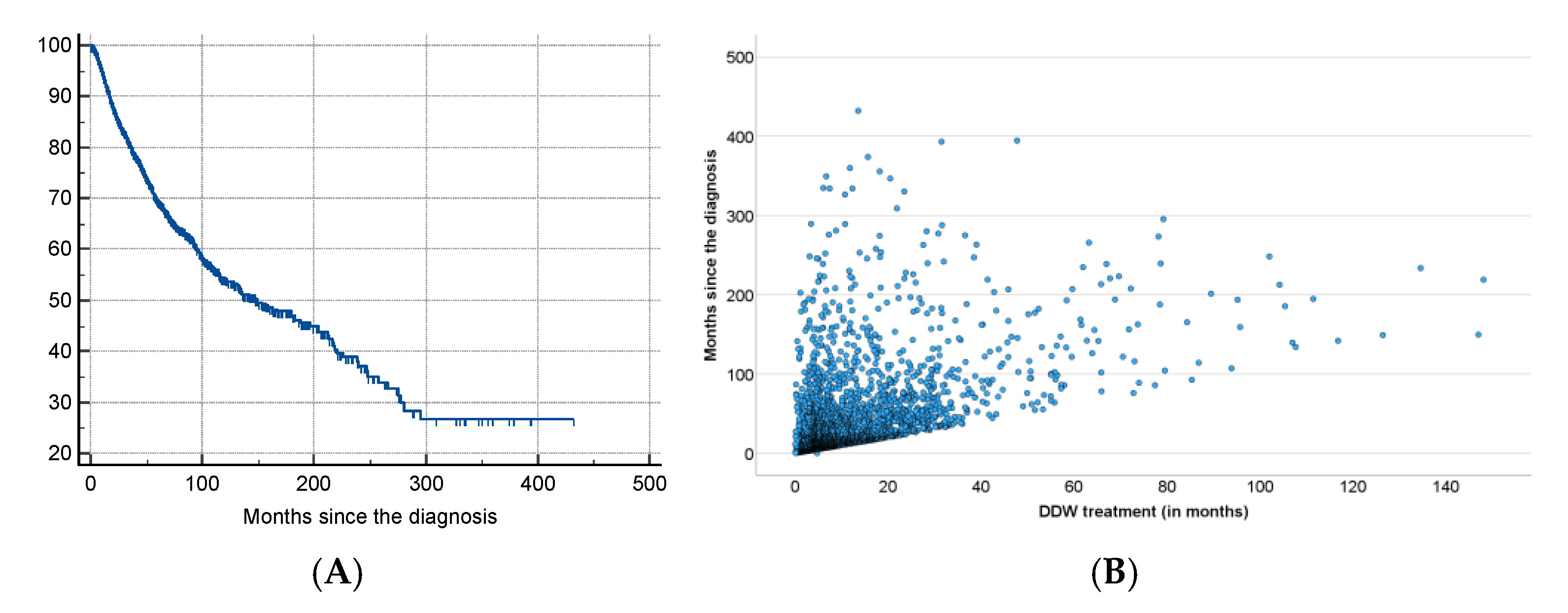

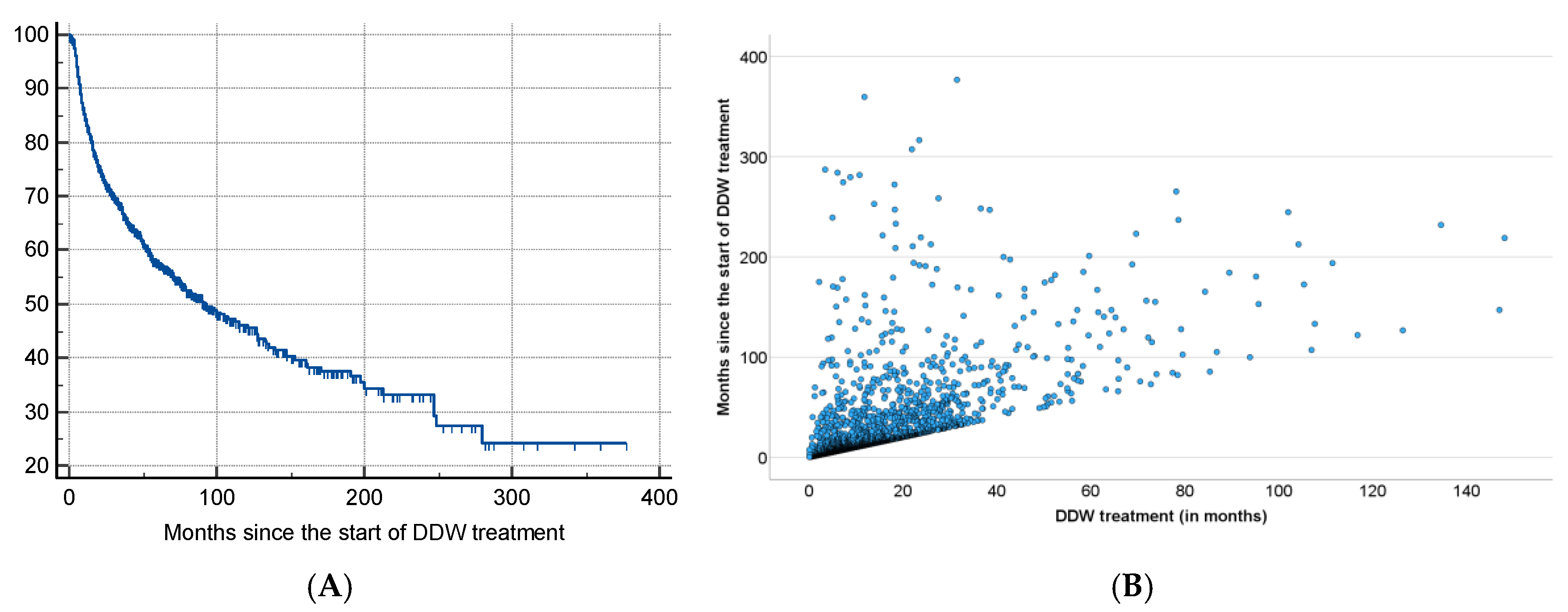

The primary endpoint of the study was survival. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates, and a log-rank test were used to compare groups. The statistical analysis compared the MST value of the 2,649 patients with the historical control data, calculated at 2.4 years. A detailed analysis of the underlying factors behind the given MST value was conducted to minimize the likelihood of potential errors. We examined the factors influencing MST and analyzed and investigated the relationship and interaction between multiple factors. The data in

Table 2 indicates that the average time from diagnosis to the commencement of DDW consumption was 19 months. To accurately assess the efficacy of DDW consumption, the MST was calculated from both the date of diagnosis and the initiation of DDW consumption, as the patients already exhibit prolonged survival from the time of diagnosis before starting DDW. All statistical computations were performed by using the software SPSS v25. The study was performed retrospectively, and all statistical results were declared significant with p < 0.05. For correlation analysis, the Pearson method was used. The calculations were performed by Adware Research Ltd. (Balatonfüred, Hungary).

Discussion

There is no doubt that significant advances have been made in cancer therapy over the past decades. However, prognoses show that current treatments have not led—and are unlikely to lead—to a true breakthrough in oncology.7 The greatest paradox of the prevailing approach is that, despite recognizing the immense complexity of genetic and biochemical processes of the cells, we seek solutions by targeting specific genetic mutations or using single molecules to selectively inhibit or influence isolated processes or, more precisely, the functional proteins responsible for them.

More than forty years ago Albert Szent-Györgyi raised the question of whether harmonic regulation of the rapid and complex biochemical and genetic processes of a cell is (or can be) realized at the molecular level. He assumed that large protein molecules (the typical main targets of drug development) were incapable of regulating these processes, and stated that a sub-molecular regulatory system, based on electrons—very lightweight and mobile elementary particles -, fulfills this role.28 The data obtained with DDW7-10 confirmed that sub-molecular changes, namely, increase or decrease of D/H ratio, significantly impact the processes within the cells.

This cellular effect of altering the D/H ratio by deuterium depletion resulted at a systemic level in a severalfold increase in the median survival time (MST) of cancer patients consuming DDW in the studies referred to above19-22 compared to historical controls. These findings underscore the importance of identifying key parameters for fully harnessing the potential of deuterium depletion when integrating it into conventional cancer therapy.

The results of the present study, based on real-world data of 2,649 patients consuming DDW, showed the possible significant impact of integrating deuterium depletion into conventional oncotherapy, and highlighted both its potentials and limitations. The MST for the patients involved increased to 12.4 years from the time of diagnosis and to 7.6 years from the start of DDW consumption, representing a five- and three-fold increase compared to the 2.4-year MST of the overall Hungarian cancer population. Among the patients with detectable tumors (TG group) MST was 5.8 years from the initiation of DDW consumption. In the RG group (patients in remission when starting deuterium depletion) MST from the start of DDW consumption was 23.2 years.

To find the optimal conditions for integrating DDW into conventional therapy, subgroups within the 2,649 cases were defined based on time parameters (see

Tables 4, 5, 6 and 8), and their MST was analyzed. It was concluded that, to maximize the efficacy of DDW, a life expectancy of not less than 3-4 months at the start of DDW consumption is necessary, the length of DDW consumption should be longer than 90-120 days, and DDW consumption should start not later than 9 months after diagnosis. The evidence for these requirements, MST data for all the subgroups calculated from the start of DDW consumption, are summarized in

Table 9.

The data showed that excluding patients with a short application period (who died within 90–120 days after start of DDW or who consumed DDW for less than 90–120 days) increased the MST from 5.8 years to 6.1–6.5 years. When both criteria were applied, MST for patients who lived longer than 90–120 days and consumed DDW for more than 90–120 days went up to 8.0–8.7 years.

However, the most critical factor, highlighted by the numbers in

Table 9, was the time gap between diagnosis and initiation of DDW consumption. When DDW consumption started within 9 months after diagnosis, the MST rose to 11.3 years (95% CI: 8.4–14.1), but it dropped to 9.6 years (95% CI: 7.2-11.8) starting over a year after diagnosis. When the calculation was restricted to patients who lived longer than 120 days after starting DDW and consumed it for more than 120 days, only a minimal additional increase in MST (to 11.6 years) was observed.

This population, who began to use DDW within 9 months after diagnosis, achieved a nearly 5-fold increase in MST compared to the average Hungarian cancer population, emphasizing the importance of timely and sustained DDW consumption in improving survival outcomes.

With an MST of 11.6 years, Hungary’s annual cancer death toll could drop from 33,000 to approximately 5,000–7,000, potentially saving 26,000–28,000 lives each year. In Europe, the cancer death toll could be reduced by 825,000 to 880,000 lives through the integration of deuterium depletion into conventional therapy. This represents a dramatic improvement for the cancer population, underscoring the potential life-saving impact of integrating DDW consumption into therapy.

Deuterium depletion constitutes a paradigm-shifting approach by abandoning the focus on single targets within the cell regulation. Gene expression studies indeed demonstrated that altering deuterium concentration had a profound impact on entire cells or organisms.

In humans, 200–300 genes regulate the cell cycle directly, while many additional genes indirectly engage in related signaling pathways and repair mechanisms. Two previous studies[

25,

30] demonstrated that the expression of specific genes associated with tumor development, such as c-Myc and K-Ras, H-Ras, Bcl2, p53, was inhibited in carcinogen-treated mice consuming DDW. This suggests a potential role of intracellular deuterium level in modulating gene expression linked to tumorigenesis, offering promising insights for future research and therapeutic applications.

An elevated D/H ratio seems thus essential for triggering the expression of specific genes associated with tumor development. A recent study[

31] utilizing nanostring technology investigated the expression of 236 cancer-related genes and 536 kinase genes in deuterium-depleted (40 and 80 ppm D), deuterium-enriched (300 ppm), and regular (150 ppm) media. From the total, 124 cancer-related genes and 135 kinase genes (those with expression changes exceeding 30% and a copy number above 30) were evaluated.

Only seven genes exhibited altered expressions (one upregulated and six downregulated) in deuterium-depleted media, but 97.3% of the evaluated genes were upregulated on deuterium enrichment. These findings align with the above-mentioned

in vivo mouse studies, demonstrating that DDW keeps the D concentration at a low level and inhibits its rise to the threshold necessary to trigger the expression of genes induced by carcinogens. Research confirmed that consuming DDW prevents the increase in the D/H ratio, thereby blocking the activation of the entire set of genes involved in cell cycle regulation. In harmony with these results, a cell cycle analysis revealed that DDW caused cell cycle arrest in the G1/S transition, reduced the number of cells in the S phase, and significantly increased the population of cells in the G1 phase.[

32]

DDW reduces the body’s deuterium concentration[

33] effectively mimicking the role of mitochondria in producing deuterium-depleted metabolic water. Studies suggest that lowering deuterium levels impacts cellular metabolism and generates free radicals[

29], demanding rapid and efficient adaptive responses. Healthy cells with fully functional mitochondria and metabolism can successfully manage this metabolic challenge. In contrast, cancer cells, which typically lack such mitochondrial functionality, fail to adapt, leading to apoptosis, necrosis, and observable tumor regression.[

9,

10]

Safety is a primary concern in the case of any novel therapeutic method to be applied in humans. As for deuterium depletion, the consumption of DDW with 25–125 ppm deuterium content has proven to be safe, with no unexpected toxic or harmful effects observed.[

19,

26,

27] In contrast, some beneficial effects beyond tumor growth inhibition were observed. In a Phase 2 clinical trial involving 30 patients with pre or manifest diabetes, significant increase in blood cell counts within the normal range and a reduction in fasting blood glucose levels were observed.[

26] These findings were consistent with observations in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and consuming DDW, where significant blood count deterioration was either absent or delayed. A general improvement in the patients’ physical strength and well-being, associated with DDW consumption, was also repeatedly found. The underlying mechanism is likely the one described in a test with top athletes, where a 44-day regimen of 105 ppm DDW consumption resulted in a delayed increase in lactic acid levels and a reduced anion gap, indicating more efficient mitochondrial function.[

27]

On the other hand, tumor necrosis caused by deuterium depletion was not without some kind of side effects. The most characteristic changes were weakness, drowsiness, increased temperature, fever spikes, intermittently increasing pain, swelling, and softening of the tumor-affected area, minor bleeding in the bladder, stomach, or rectum, brick dust urine, and transient coughing in lung cancer.24 All these side effects were tolerable by the patients and were transient.

In several cases, patients involved in the present study used various supplementary or alternative treatments in parallel with conventional oncotherapy and DDW consumption, and the data suggested a possible negative interaction between deuterium depletion and certain supplementary methods. After a thorough evaluation, several factors were identified that significantly diminished the effectiveness of DDW or rendered it entirely ineffective. These included high doses of antioxidants, such as vitamins A, C, E, and selenium; consumption of Coenzyme Q10 supplements; iron supplementation; intense and prolonged physical exertion; as well as the use of hot tubs and saunas. Understanding these influences can provide critical guidance for optimizing the efficacy of DDW application and highlights the importance of managing patient lifestyles and supplementary treatments during deuterium depletion.

The groundbreaking findings in this study underscore the pivotal role of the D/H ratio in regulating and coordinating millions of molecular processes, including biochemical and genetic functions involved in carcinogenesis. At the eukaryotic level, a sub-molecular regulatory system (SMRS) governs the intricate complexity of life. Utilization of the capacities of DDW enables an intervention in this fundamental regulatory system, opening new avenues for therapeutic applications and a deeper understanding of cellular processes.

Supported by HYD LLC for Cancer Research and Drug Development, Budapest, Hungary

We sincerely thank the patients consuming DDW and their families for voluntarily sharing their experiences and outcomes before, during, and after DDW consumption. Their insights, along with the results of follow-up oncology examinations confirming the effectiveness of conventional treatments, are invaluable.