Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

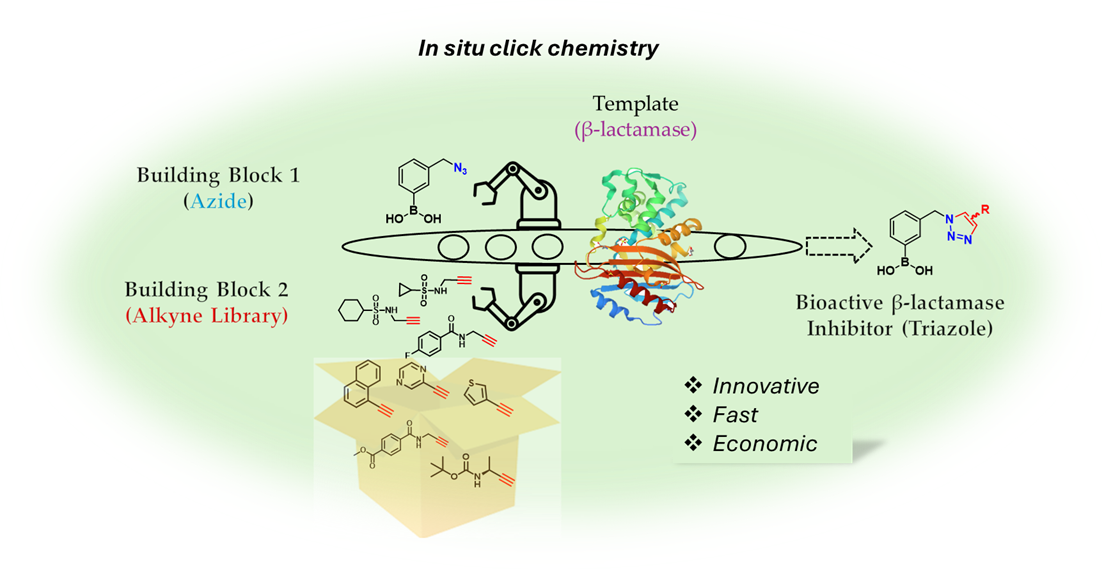

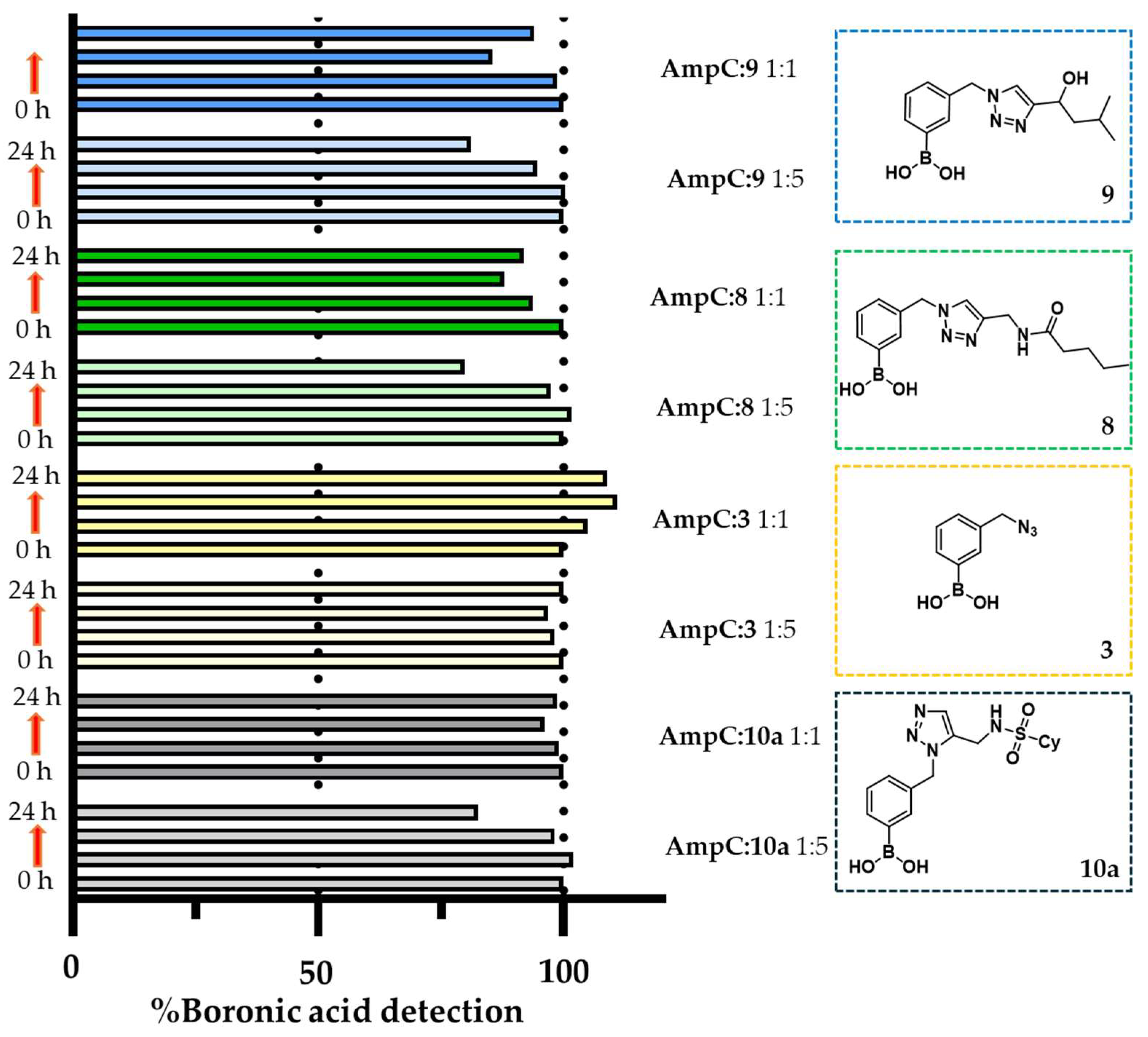

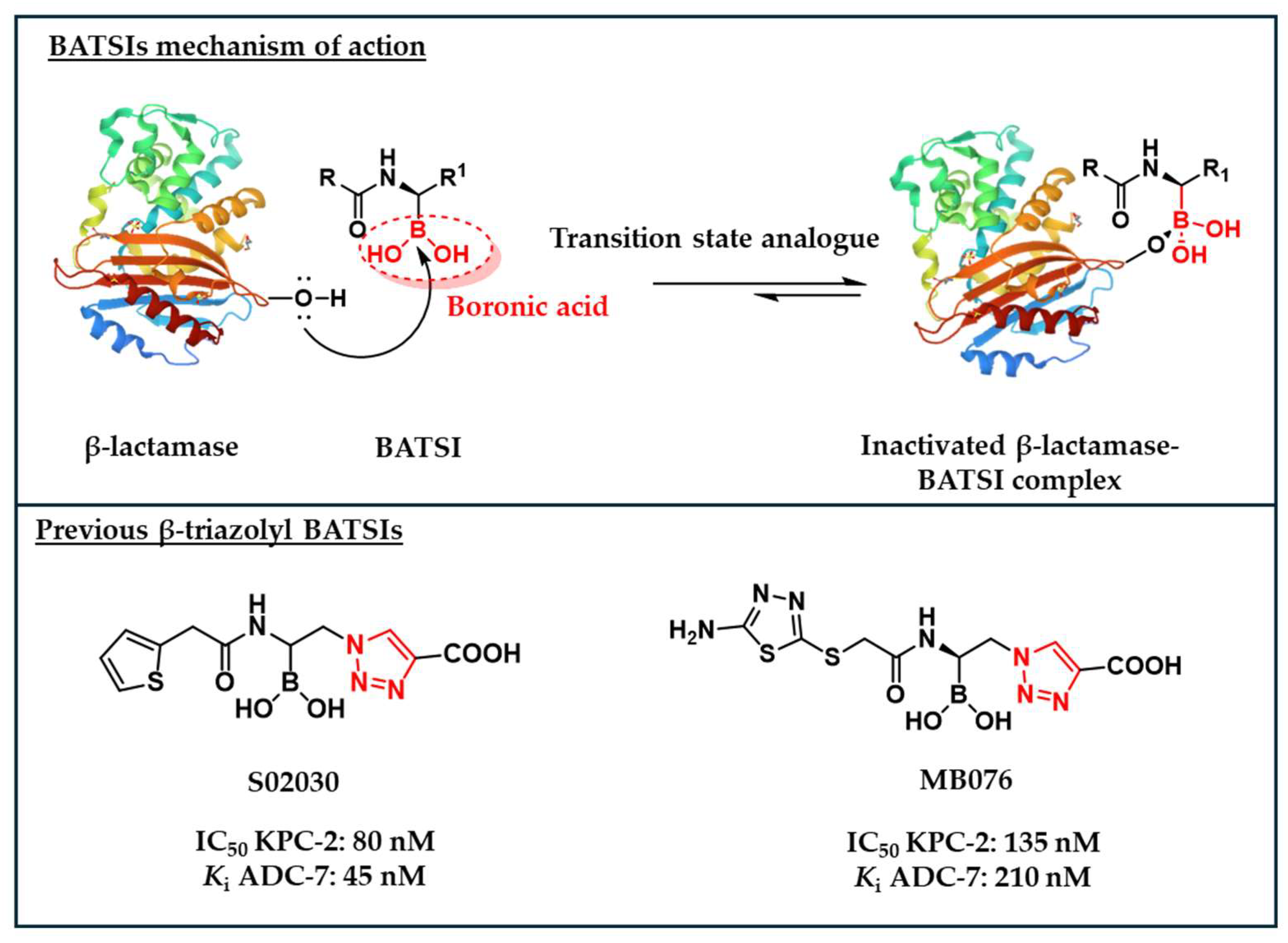

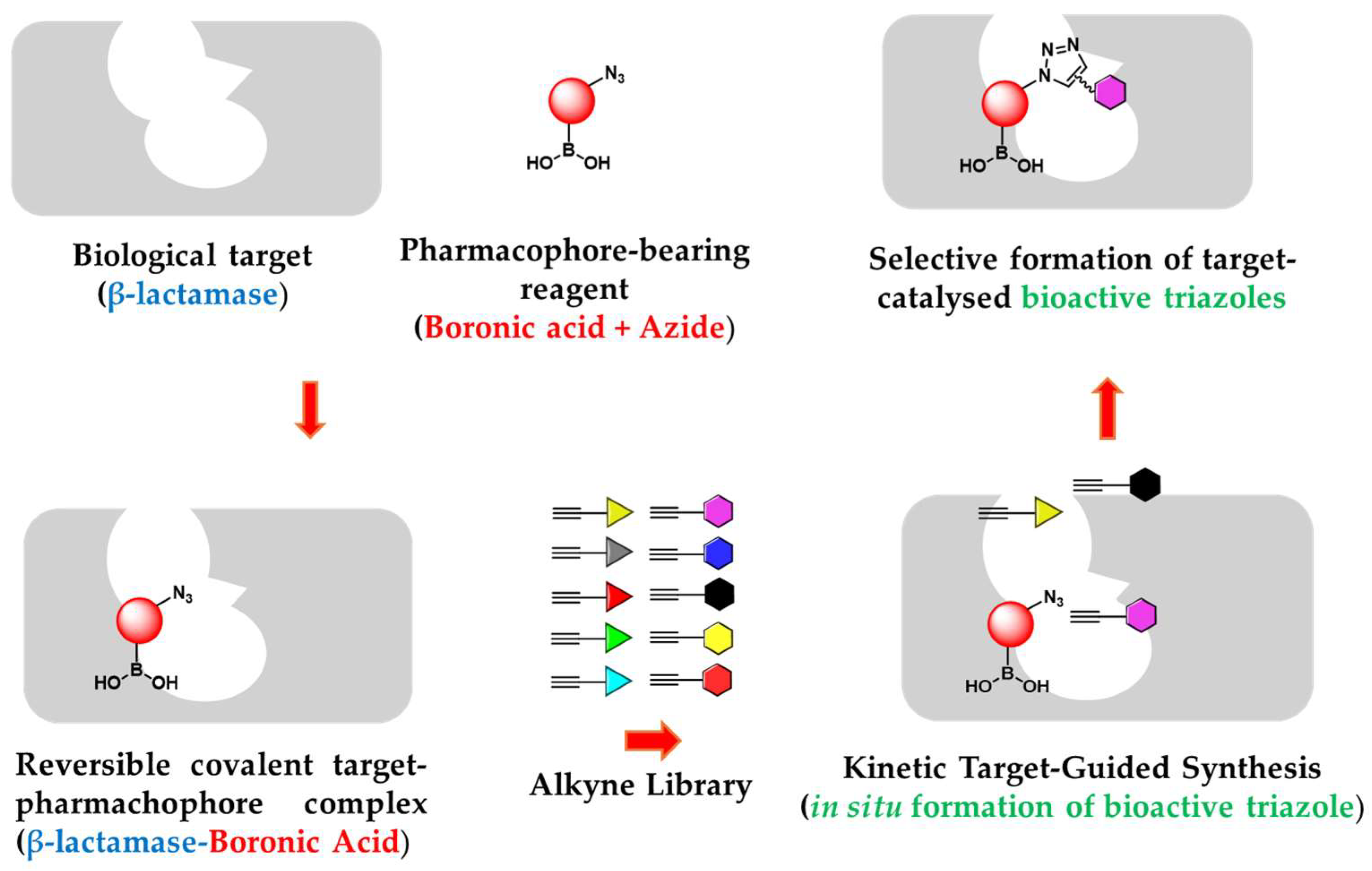

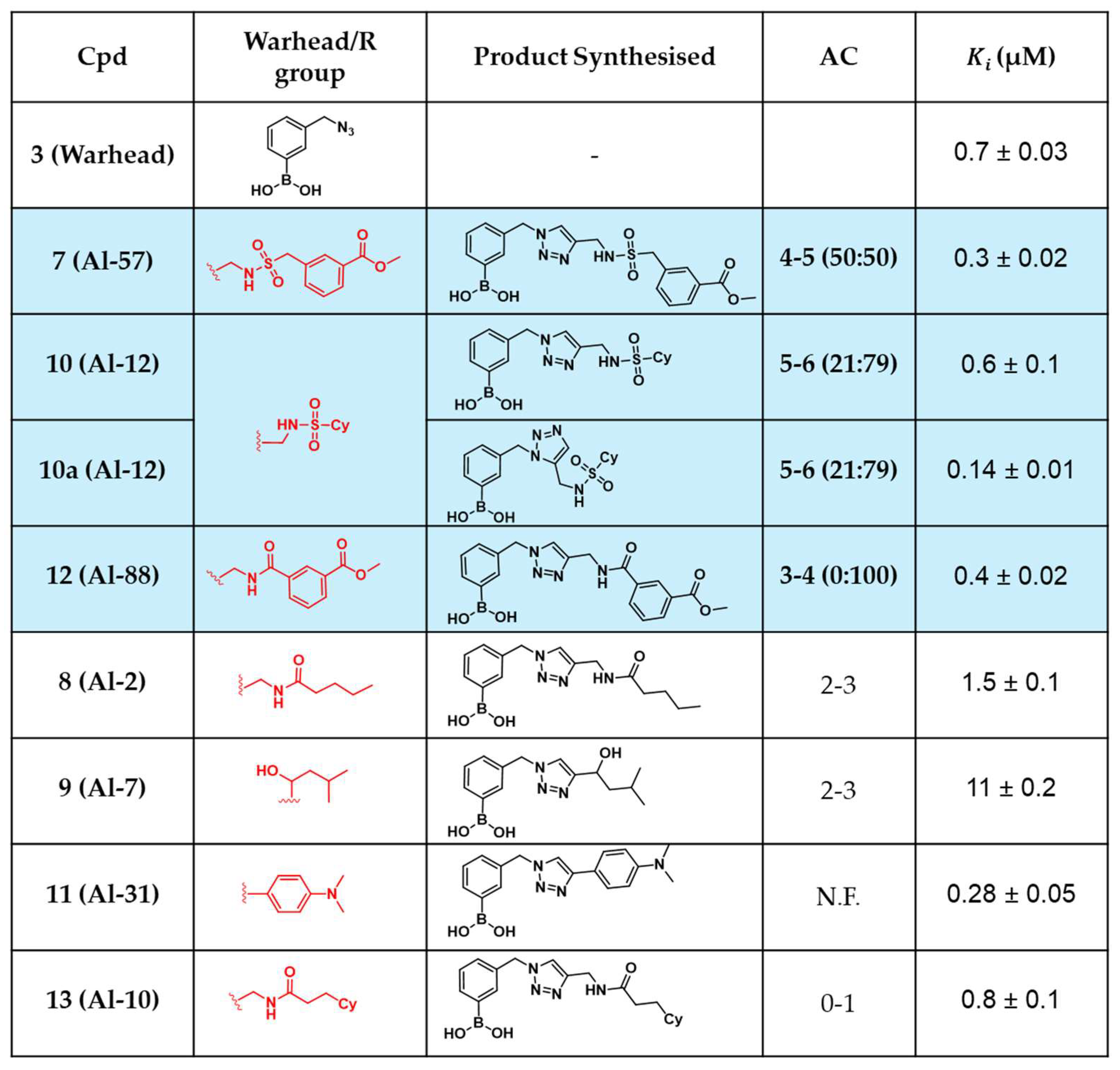

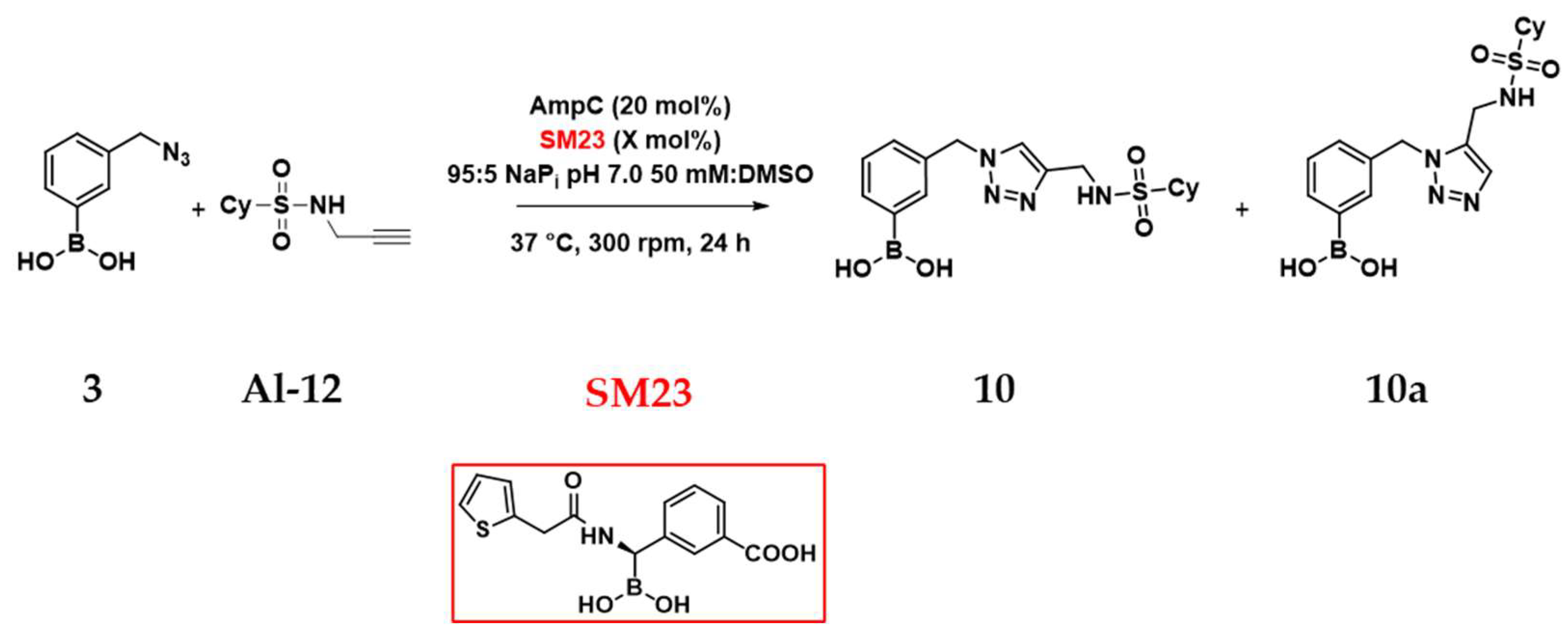

In this study we evaluated in situ click chemistry as platform for discovering boronic acid-based β-lactamase inhibitors (BLIs). Unlike conventional drug discovery approaches requiring multi-step synthesis, protection strategies, and extensive screening, the in situ method can allow the generation and identification of potent β-lactamase inhibitors in a rapid, economic and efficient way. Using KPC-2 (class A carbapenemase) and AmpC (class C cephalosporinase) as templates, we demonstrated their ability to catalyse azide-alkyne cycloaddition, facilitating the formation of triazole-based β-lactamase inhibitors. Initial screening of various β-lactamases and boronic warheads identified compound 3 (3-azidomethylphenyl boronic acid) as the most effective scaffold for Kinetic Target-Guided Synthesis (KTGS). KTGS experiments with AmpC and KPC-2 yielded triazole inhibitors with Ki values as low as 140 nM (compound 10a, AmpC) and 730 nM (compound 5, KPC-2). Competitive inhibition studies confirmed triazole formation within the active site, while LC-MS analysis verified that the reversible covalent interaction of boronic acids did not affect detection of the in situ synthesised product. While KTGS successfully identified potent inhibitors, limitations in amplification coefficients and spatial constraints highlight the need for optimised warhead designs. This study validates KTGS as a promising strategy for BLI discovery and provides insights for further refinement in fighting β-lactamase-mediated antibiotic resistance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

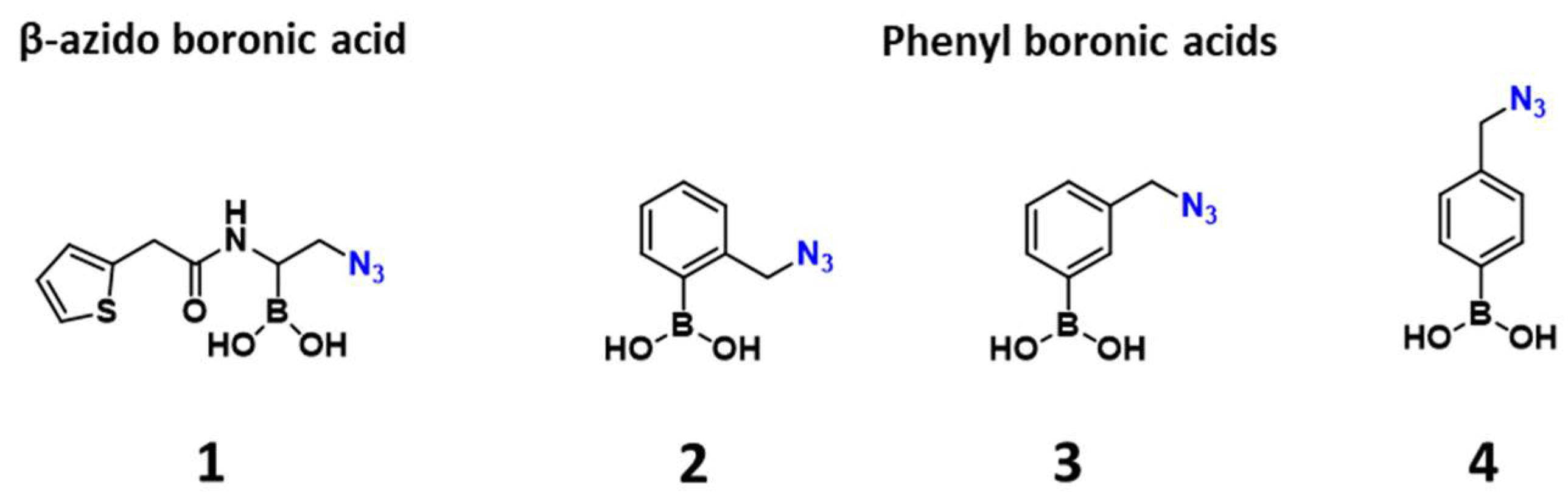

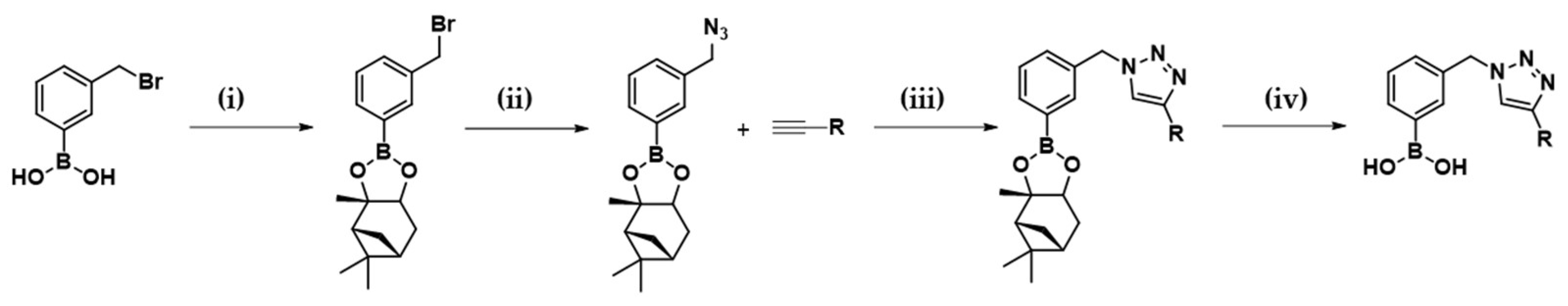

2.1. Design and Synthesis of the Warhead

2.2. Inhibition (%) of the Warheads on Representative BLs

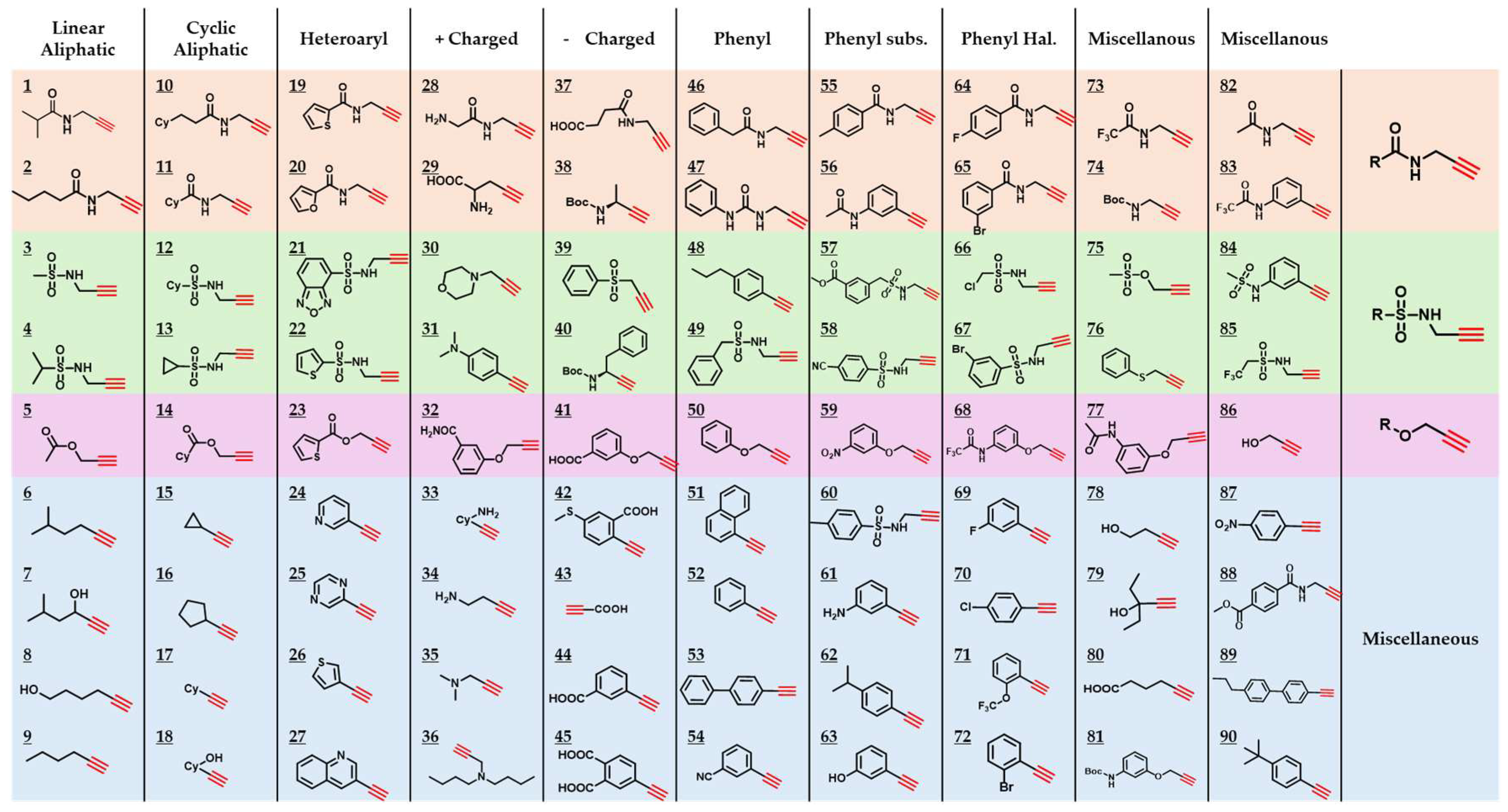

2.3. Generation of a 90-Component Alkyne Library

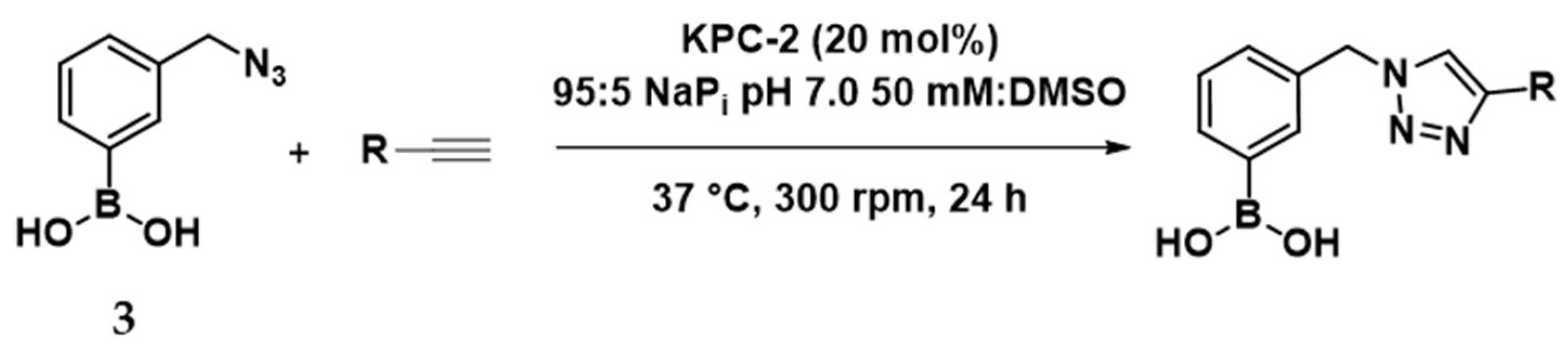

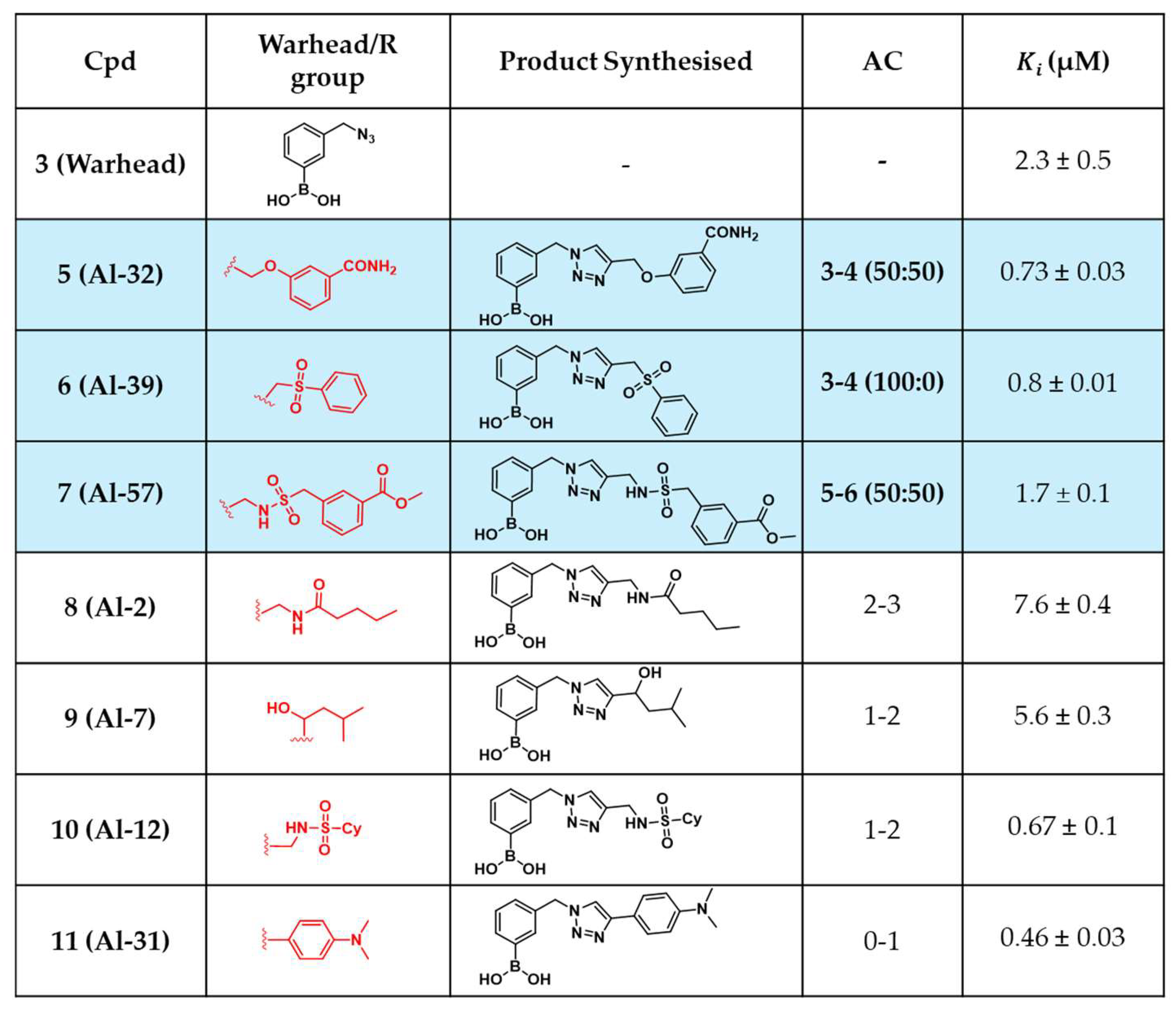

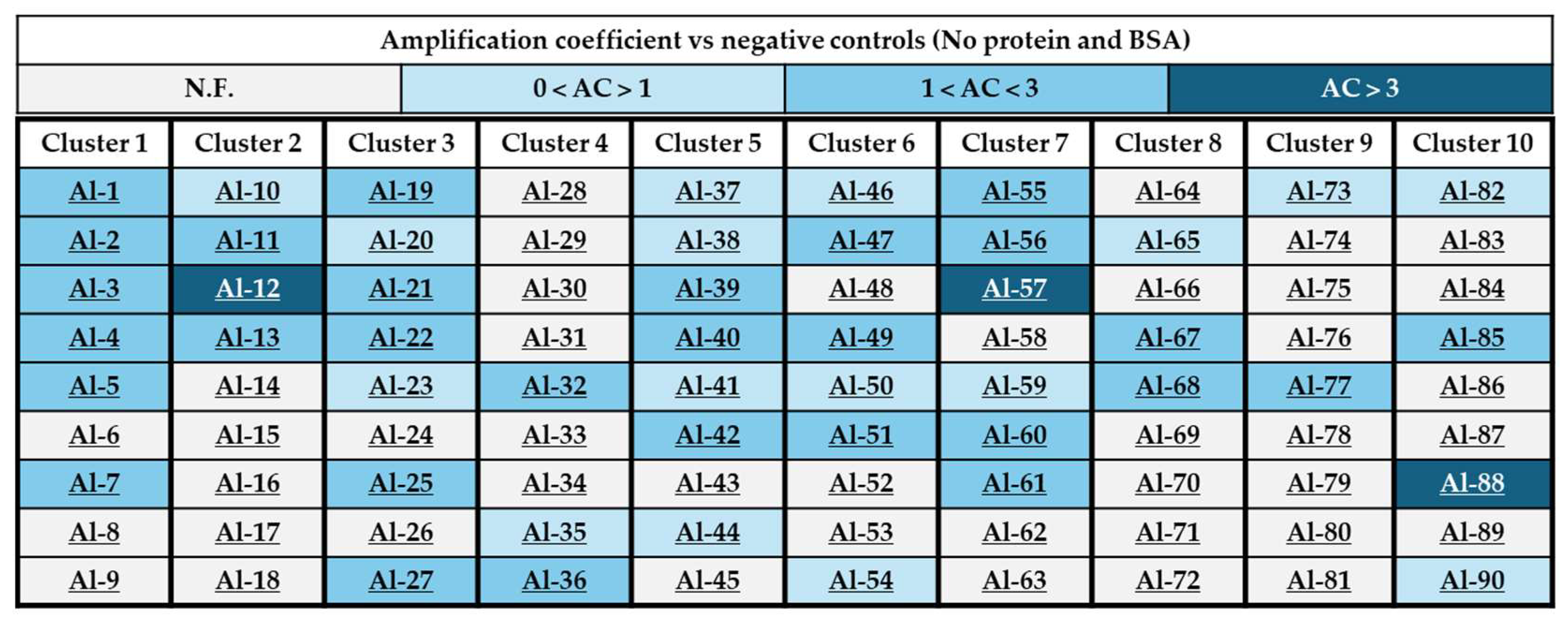

2.4. In Situ Click Chemistry with KPC-2

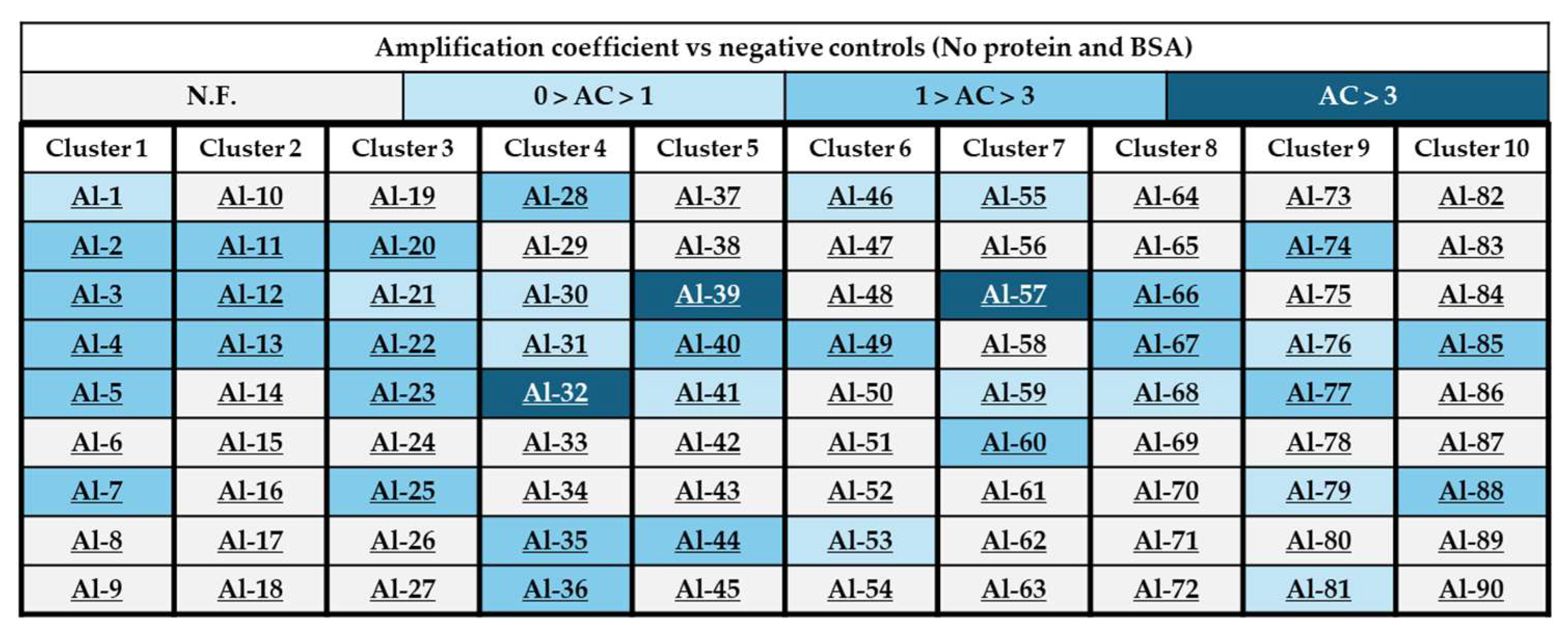

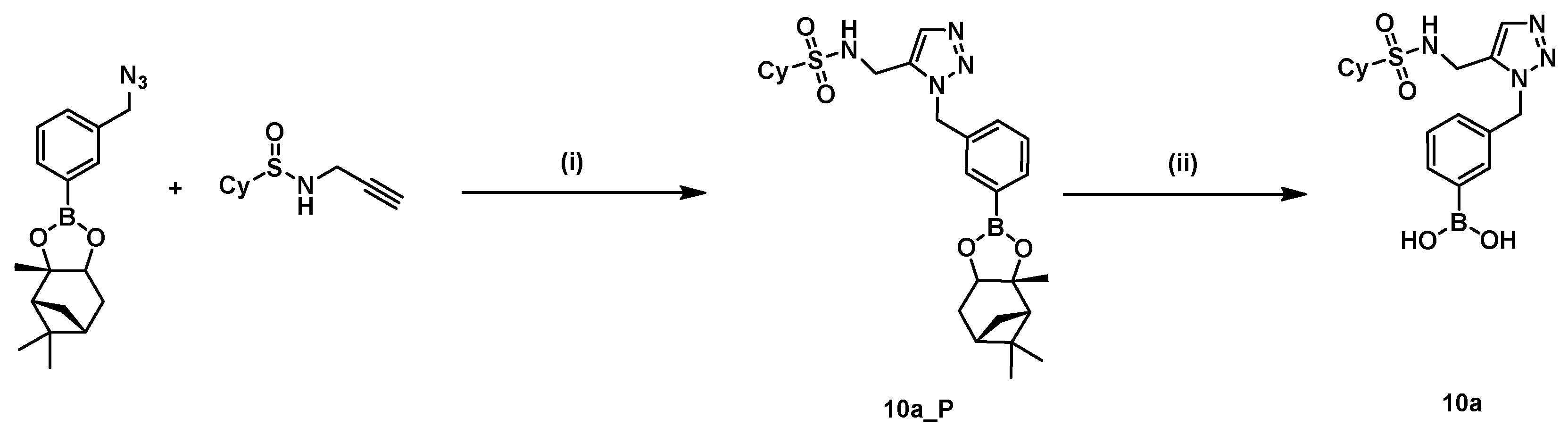

2.5. In Situ Click Chemistry with AmpC

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.2. In Situ Click Chemistry

4.3. Microbiology and Determination of Ki

| β-lactamase | Buffer | Substrate | KM substrate | [Substrate] | [β-lactamase] |

| KPC-2 | NaPi1 | NCF3 | 10 ± 1 μM | 50 μM | 1 nM |

| CTX-M-15 | NaPi | NCF | 35 ± 1 μM | 25 μM | 2.5 nM |

| KPC-53 | NaPi | NCF | 106 ± 2 μM | 100 μM | 30 nM |

| SHV-12 | NaPi | NCF | 50 ± 3 μM | 25 μM | 7 nM |

| NDM-1 | HEPES2 | MPM4 | 80 ± 1 μM | 100 μM | 4.5 nM |

| VIM-1 | HEPES | MPM | 130 ± 4 μM | 150 μM | 22 nM |

| IMP-1 | HEPES | MPM | 30 ± 1 μM | 80 μM | 13 nM |

| AmpC | NaPi | NCF | 118 ± 2 μM | 142 μM | 14 nM |

| ADC-25 | NaPi | NCF | 120 ± 3 μM | 24 μM | 3 nM |

| CMY-2 | NaPi | NCF | 8 ± 1 μM | 24 μM | 2.5 nM |

| OXA-24 | NaPi | NCF | 29 ± 1 μM | 142 μM | 4 nM |

| OXA-48 | NaPi | IMI5 | 13 ± 1 μM | 50 μM | 75 nM |

| 1 NaPi 50 mM pH 7.0; 2 HEPES 20 mM pH 7.0+ 20 μM Zn. 3 NCF = Nitrocefin; 4 MPM = Meropenem; 5 IMI = Imipenem. | |||||

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tang, S.S.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; Hsu, L.Y. Mechanisms of β-lactam antimicrobial resistance and epidemiology of major community- and healthcare-associated multidrug-resistant bacteria. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2014, 78, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.M.; Silva, B.N.M.d.; Barbosa, G.; Barreiro, E.J. β-lactam antibiotics: An overview from a medicinal chemistry perspective. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 208, 112829. [Google Scholar]

- Docquier, J.-D.; Mangani, S. An update on β-lactamase inhibitor discovery and development. Drug Resistance Updates 2018, 36, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Liao, X.; Ding, T.; Ahn, J. Role of β-Lactamase Inhibitors as Potentiators in Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Targeting Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munita Jose, M.; Arias Cesar, A. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiology Spectrum 2016, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, E.M.; Trampari, E.; Siasat, P.; Gaya, M.S.; Alav, I.; Webber, M.A.; Blair, J.M.A. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance revisited. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 280–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.G.; Barlow, M. Revised Ambler classification of β-lactamases. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2005, 55, 1050–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Tooke, C.L.; Hinchliffe, P.; Bragginton, E.C.; Colenso, C.K.; Hirvonen, V.H.A.; Takebayashi, Y.; Spencer, J. β-Lactamases and β-Lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. Journal of Molecular Biology 2019, 431, 3472–3500. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, K.; Jacoby George, A. Updated Functional Classification of β-Lactamases. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2010, 54, 969–976. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, B.G.; Barlow, M. Evolution of the serine β-lactamases: past, present and future. Drug Resistance Updates 2004, 7, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford Patricia, A. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in the 21st Century: Characterization, Epidemiology, and Detection of This Important Resistance Threat. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2001, 14, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, M.; Simner, P.J.; Bradford, P.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: an update on their characteristics, epidemiology and detection. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance 2021, 3, dlab092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammoudi Halat, D.; Ayoub Moubareck, C. The Current Burden of Carbapenemases: Review of Significant Properties and Dissemination among Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenic, B.; Plecko, V.; Sardelic, S.; Uzunovic, S.; Torkar, K.G. Carbapenemases in Gram-Negative Bacteria: Laboratory Detection and Clinical Significance. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Codjoe, F.S.; Donkor, E.S. Carbapenem Resistance: A Review. Medical Sciences 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, K.; Bradford, P.A. Interplay between β-lactamases and new β-lactamase inhibitors. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2019, 17, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, E.; Romagnoli, C.; Vahabi, R.; Taracila, M.A.; Bonomo, R.A.; Prati, F. Click Chemistry in Lead Optimization of Boronic Acids as β-Lactamase Inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 58, 5445–5458. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, E.; Romagnoli, C.; Powers, R.A.; Taracila, M.A.; Bouza, A.A.; Swanson, H.C.; Smolen, K.A.; Fini, F.; Wallar, B.J.; Bonomo, R.A.; et al. Inhibition of Acinetobacter-Derived Cephalosporinase: Exploring the Carboxylate Recognition Site Using Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitors. ACS Infectious Diseases 2018, 4, 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, T.; Furukawa, N.; Caselli, E.; Prati, F.; Taracila, M.A.; Bethel, C.R.; Ishii, Y.; Shimizu-Ibuka, A.; Bonomo, R.A. Insights Into the Inhibition of MOX-1 β-Lactamase by S02030, a Boronic Acid Transition State Inhibitor. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, L.J.; Taracila, M.A.; Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Bethel, C.R.; Caselli, E.; Romagnoli, C.; Winkler, M.L.; Spellberg, B.; Prati, F.; Bonomo, R.A. Boronic Acid Transition State Inhibitors Active against KPC and Other Class A β-Lactamases: Structure-Activity Relationships as a Guide to Inhibitor Design. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 60 60, 1751–1759.

- Winkler, M.L.; Rodkey, E.A.; Taracila, M.A.; Drawz, S.M.; Bethel, C.R.; Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Smith, K.M.; Xu, Y.; Dwulit-Smith, J.R.; Romagnoli, C.; et al. Design and Exploration of Novel Boronic Acid Inhibitors Reveals Important Interactions with a Clavulanic Acid-Resistant Sulfhydryl-Variable (SHV) β-Lactamase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 56, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamrick Jodie, C.; Docquier, J.-D.; Uehara, T.; Myers Cullen, L.; Six David, A.; Chatwin Cassandra, L.; John Kaitlyn, J.; Vernacchio Salvador, F.; Cusick Susan, M.; Trout Robert, E.L.; et al. VNRX-5133 (Taniborbactam), a Broad-Spectrum Inhibitor of Serine- and Metallo-β-Lactamases, Restores Activity of Cefepime in Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2020, 64, 10.1128–aac.01963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajnc, A.; Brem, J.; Hinchliffe, P.; Calvopiña, K.; Panduwawala, T.D.; Lang, P.A.; Kamps, J.J.A.G.; Tyrrell, J.M.; Widlake, E.; Saward, B.G.; et al. Bicyclic Boronate VNRX-5133 Inhibits Metallo- and Serine-β-Lactamases. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 62, 8544–8556. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Trout, R.E.L.; Chu, G.-H.; McGarry, D.; Jackson, R.W.; Hamrick, J.C.; Daigle, D.M.; Cusick, S.M.; Pozzi, C.; De Luca, F.; et al. Discovery of Taniborbactam (VNRX-5133): A Broad-Spectrum Serine- and Metallo-β-lactamase Inhibitor for Carbapenem-Resistant Bacterial Infections. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 63, 2789–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenlehner Florian, M.; Gasink Leanne, B.; McGovern Paul, C.; Moeck, G.; McLeroth, P.; Dorr, M.; Dane, A.; Henkel, T. Cefepime–Taniborbactam in Complicated Urinary Tract Infection. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, 611–622. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker, S.J.; Reddy, K.R.; Lomovskaya, O.; Griffith, D.C.; Rubio-Aparicio, D.; Nelson, K.; Tsivkovski, R.; Sun, D.; Sabet, M.; Tarazi, Z.; et al. Discovery of Cyclic Boronic Acid QPX7728, an Ultrabroad-Spectrum Inhibitor of Serine and Metallo-β-lactamases. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 63, 7491–7507. [Google Scholar]

- Tsivkovski, R.; Totrov, M.; Lomovskaya, O. Biochemical Characterization of QPX7728, a New Ultrabroad-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Inhibitor of Serine and Metallo-Beta-Lactamases. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 64 64, e00130-00120. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.M.C.; Consol, P.; Chen, Y. Drug Discovery in the Field of β-Lactams: An Academic Perspective. Antibiotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.A.; Caselli, E.; Focia, P.J.; Prati, F.; Shoichet, B.K. Structures of Ceftazidime and Its Transition-State Analogue in Complex with AmpC β-Lactamase: Implications for Resistance Mutations and Inhibitor Design. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 9207–9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drawz, S.M.; Babic, M.; Bethel, C.R.; Taracila, M.; Distler, A.M.; Ori, C.; Caselli, E.; Prati, F.; Bonomo, R.A. Inhibition of the Class C β-Lactamase from Acinetobacter spp.: Insights into Effective Inhibitor Design. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 329–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, W.; Sampson Jared, M.; Ori, C.; Prati, F.; Drawz Sarah, M.; Bethel Christopher, R.; Bonomo Robert, A.; van den Akker, F. Novel Insights into the Mode of Inhibition of Class A SHV-1 β-Lactamases Revealed by Boronic Acid Transition State Inhibitors. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2011, 55, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eidam, O.; Romagnoli, C.; Caselli, E.; Babaoglu, K.; Pohlhaus, D.T.; Karpiak, J.; Bonnet, R.; Shoichet, B.K.; Prati, F. Design, Synthesis, Crystal Structures, and Antimicrobial Activity of Sulfonamide Boronic Acids as β-Lactamase Inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2010, 53, 7852–7863. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, E.; Fini, F.; Introvigne, M.L.; Stucchi, M.; Taracila, M.A.; Fish, E.R.; Smolen, K.A.; Rather, P.N.; Powers, R.A.; Wallar, B.J.; et al. 1,2,3-Triazolylmethaneboronate: A Structure Activity Relationship Study of a Class of β-Lactamase Inhibitors against Acinetobacter baumannii Cephalosporinase. ACS Infectious Diseases 2020, 6, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introvigne, M.L.; Taracila, M.A.; Prati, F.; Caselli, E.; Bonomo, R.A. α-Triazolylboronic Acids: A Promising Scaffold for Effective Inhibitors of KPCs. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 1283–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.A.; June, C.M.; Fernando, M.C.; Fish, E.R.; Maurer, O.L.; Baumann, R.M.; Beardsley, T.J.; Taracila, M.A.; Rudin, S.D.; Hujer, K.M.; et al. Synthesis of a Novel Boronic Acid Transition State Inhibitor, MB076: A Heterocyclic Triazole Effectively Inhibits Acinetobacter-Derived Cephalosporinase Variants with an Expanded-Substrate Spectrum. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 66, 8510–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.Q.; Krishnan, N.P.; Rojas, L.J.; Prati, F.; Caselli, E.; Romagnoli, C.; Bonomo, R.A.; van den Akker, F. Crystal Structures of KPC-2 and SHV-1 β-Lactamases in Complex with the Boronic Acid Transition State Analog S02030. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 60 60, 1760–1766.

- Neumann, S.; Biewend, M.; Rana, S.; Binder, W.H. The CuAAC: Principles, Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysts, and Novel Developments and Applications. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2020, 41, 1900359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, X.; Bai, R. Click chemistry-aided drug discovery: A retrospective and prospective outlook. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 264, 116037. [Google Scholar]

- Bosc, D.; Camberlein, V.; Gealageas, R.; Castillo-Aguilera, O.; Deprez, B.; Deprez-Poulain, R. Kinetic Target-Guided Synthesis: Reaching the Age of Maturity. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 63, 3817–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Kaur, J.; Wuest, M.; Wuest, F. In situ click chemistry generation of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, M.; Muldoon, J.; Lin, Y.-C.; Silverman, S.M.; Lindstrom, W.; Olson, A.J.; Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B.; Elder, J.H.; et al. Inhibitors of HIV-1 Protease by Using In Situ Click Chemistry. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2006, 45, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirose, T.; Sunazuka, T.; Sugawara, A.; Endo, A.; Iguchi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Ui, H.; Shiomi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Sharpless, K.B.; et al. Chitinase inhibitors: extraction of the active framework from natural argifin and use of in situ click chemistry. The Journal of Antibiotics 2009, 62, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grimster, N.P.; Stump, B.; Fotsing, J.R.; Weide, T.; Talley, T.T.; Yamauchi, J.G.; Nemecz, Á.; Kim, C.; Ho, K.-Y.; Sharpless, K.B.; et al. Generation of Candidate Ligands for Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors via in situ Click Chemistry with a Soluble Acetylcholine Binding Protein Template. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2012, 134, 6732–6740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tieu, W.; Soares da Costa, T.P.; Yap, M.Y.; Keeling, K.L.; Wilce, M.C.J.; Wallace, J.C.; Booker, G.W.; Polyak, S.W.; Abell, A.D. Optimising in situ click chemistry: the screening and identification of biotin protein ligase inhibitors. Chemical Science 2013, 4, 3533–3537. [Google Scholar]

- Camberlein, V.; Fléau, C.; Sierocki, P.; Li, L.; Gealageas, R.; Bosc, D.; Guillaume, V.; Warenghem, S.; Leroux, F.; Rosell, M.; et al. Discovery of the First Selective Nanomolar Inhibitors of ERAP2 by Kinetic Target-Guided Synthesis. Angewandte Chemie (International ed. in English) 2022, 61, e202203560. [Google Scholar]

- Parvatkar, P.T.; Wagner, A.; Manetsch, R. Biocompatible reactions: advances in kinetic target-guided synthesis. Trends in Chemistry 2023, 5, 657–671. [Google Scholar]

- Millward, S.W.; Agnew, H.D.; Lai, B.; Lee, S.S.; Lim, J.; Nag, A.; Pitram, S.; Rohde, R.; Heath, J.R. In situ click chemistry: from small molecule discovery to synthetic antibodies. Integrative Biology 2013, 5, 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Oueis, E.; Sabot, C.; Renard, P.-Y. New insights into the kinetic target-guided synthesis of protein ligands. Chemical Communications 2015, 51, 12158–12169. [Google Scholar]

- Manetsch, R.; Krasiński, A.; Radić, Z.; Raushel, J.; Taylor, P.; Sharpless, K.B.; Kolb, H.C. In Situ Click Chemistry: Enzyme Inhibitors Made to Their Own Specifications. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2004, 126, 12809–12818. [Google Scholar]

- Krasiński, A.; Radić, Z.; Manetsch, R.; Raushel, J.; Taylor, P.; Sharpless, K.B.; Kolb, H.C. In Situ Selection of Lead Compounds by Click Chemistry: Target-Guided Optimization of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2005, 127, 6686–6692. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, W.G.; Green, L.G.; Grynszpan, F.; Radić, Z.; Carlier, P.R.; Taylor, P.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B. Click Chemistry In Situ: Acetylcholinesterase as a Reaction Vessel for the Selective Assembly of a Femtomolar Inhibitor from an Array of Building Blocks. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2002, 41, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Unver, M.Y.; Gierse, R.M.; Ritchie, H.; Hirsch, A.K.H. Druggability Assessment of Targets Used in Kinetic Target-Guided Synthesis. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 61, 9395–9409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gladysz, R.; Vrijdag, J.; Van Rompaey, D.; Lambeir, A.-M.; Augustyns, K.; De Winter, H.; Van der Veken, P. Efforts towards an On-Target Version of the Groebke–Blackburn–Bienaymé (GBB) Reaction for Discovery of Druglike Urokinase (uPA) Inhibitors. Chemistry – A European Journal 2019, 25, 12380–12393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morandi, S.; Morandi, F.; Caselli, E.; Shoichet, B.K.; Prati, F. Structure-based optimization of cephalothin-analogue boronic acids as β-lactamase inhibitors. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2008, 16, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Stapleton, P.; Haider, S.; Healy, J. Boronic acid inhibitors of the class A β-lactamase KPC-2. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 26, 2921–2927. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Stapleton, P.; Xavier-Junior, F.H.; Schatzlein, A.; Haider, S.; Healy, J.; Wells, G. Triazole-substituted phenylboronic acids as tunable lead inhibitors of KPC-2 antibiotic resistance. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 240, 114571. [Google Scholar]

- Deprez-Poulain, R.; Hennuyer, N.; Bosc, D.; Liang, W.G.; Enée, E.; Marechal, X.; Charton, J.; Totobenazara, J.; Berte, G.; Jahklal, J.; et al. Catalytic site inhibition of insulin-degrading enzyme by a small molecule induces glucose intolerance in mice. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 8250. [Google Scholar]

- Kassu, M.; Parvatkar, P.T.; Milanes, J.; Monaghan, N.P.; Kim, C.; Dowgiallo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Asakawa, A.H.; Huang, L.; Wagner, A.; et al. Shotgun Kinetic Target-Guided Synthesis Approach Enables the Discovery of Small-Molecule Inhibitors against Pathogenic Free-Living Amoeba Glucokinases. ACS Infectious Diseases 2023, 9, 2190–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Nacheva, K.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Kassu, M.; Flanigan, D.; Monastyrskyi, A.; Iyamu, I.D.; Doi, K.; Barber, M.; Namelikonda, N.; Tipton, J.D.; et al. Going beyond Binary: Rapid Identification of Protein–Protein Interaction Modulators Using a Multifragment Kinetic Target-Guided Synthesis Approach. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 66, 5196–5207. [Google Scholar]

- Morandi, F.; Caselli, E.; Morandi, S.; Focia, P.J.; Blázquez, J.; Shoichet, B.K.; Prati, F. Nanomolar Inhibitors of AmpC β-Lactamase. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2003, 125, 685–695. [Google Scholar]

- Krajnc, A.; Lang, P.A.; Panduwawala, T.D.; Brem, J.; Schofield, C.J. Will morphing boron-based inhibitors beat the β-lactamases? Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2019, 50, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, K.B.; Manetsch, R. In situ click chemistry: a powerful means for lead discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2006, 1, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Copeland, R.A. Enzymes. A pratical Introduction to structure, mechanism and data analysis second ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Meester, F.; Joris, B.; Reckinger, G.; Bellefroid-Bourguignon, C.; Frère, J.-M.; Waley, S.G. Automated analysis of enzyme inactivation phenomena: Application to β-lactamases and DD-peptidases. Biochemical Pharmacology 1987, 36, 2393–2403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Entry | β-lactamase1 | Class | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 | KPC-22 | A | 35 | 76 | 72 |

| 2 | CTX-M-15 | 0 | 42 | 22 | |

| 3 | KPC-53 | 54 | 65 | 55 | |

| 4 | SHV-12 | 14 | 38 | 48 | |

| 5 | NDM-1 | B | 23 | 20 | 24 |

| 6 | VIM-1 | 23 | 24 | 33 | |

| 7 | IMP-1 | 12 | 11 | 22 | |

| 8 | AmpC2 | C | 57 | 100 | 81 |

| 9 | ADC-25 | 27 | 67 | 46 | |

| 10 | CMY-2 | 19 | 79 | 67 | |

| 11 | OXA-24 | D | 20 | 24 | 26 |

| 12 | OXA-48 | <1 | 2 | <1 |

| Entry* | Enzyme | %SM23 | Regioselectivity (10:10a) | AC 10/10a |

| 1 | None | - | 50:50 | - |

| 2 | BSA (20 mol%) | - | 60:40 | - |

| 3 | AmpC (20 mol%) | - | 21:79 | 5-6 |

| 4 | AmpC (20 mol%) | 1 mol% | 0:100 | 1-2 |

| 5 | AmpC (20 mol%) | 20 mol% | 50:50 | 0-1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).