Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

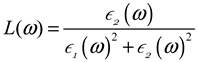

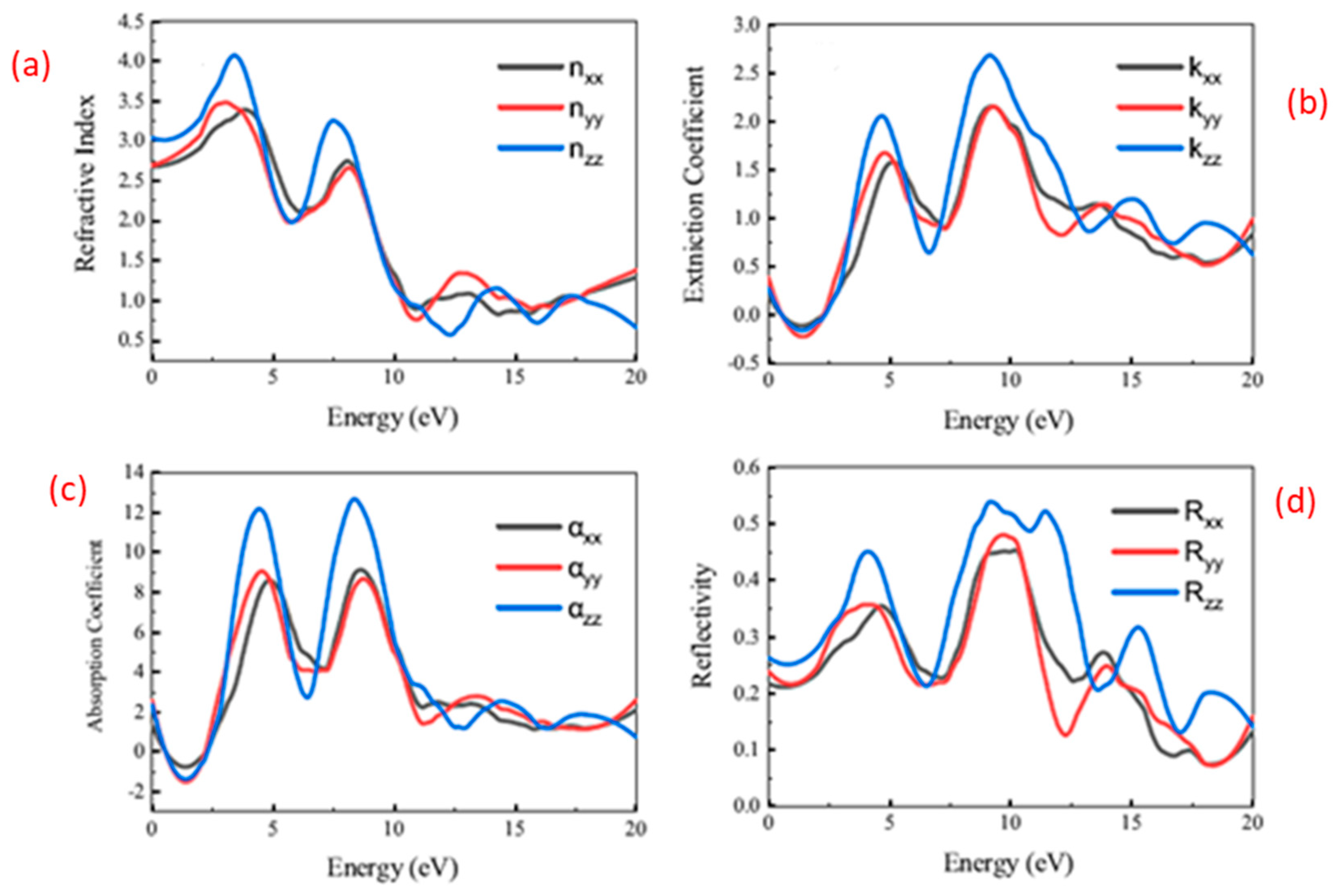

This study investigates the structural, electronic, and optical properties of anisotropic rutile titanium dioxide (TiO2) using density functional theory (DFT). The calculated lattice parameters were found to be a = b = 4.64 ˚A and c = 42.97 ˚A. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) exchange- correlation functional predicted a bandgap of 1.89 eV, in close agreement with experimental results. A detailed analysis of the density of states (DOS) and projected density of states (PDOS) further validated the accuracy of the computed bandgap. The optical properties were examined through the dielectric function, revealing real and imaginary static dielectric constants of 11.85 and 0.13, respectively. Moreover, the absorption and conductivity spectra exhibited promising behavior in the UV-visible range, indicating strong potential for water remediation and photocatalytic applications. Overall, the electronic and optical characteristics of TiO2 suggest its viability as an effective material for environmental and energy-related applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

3. Results and Discussion

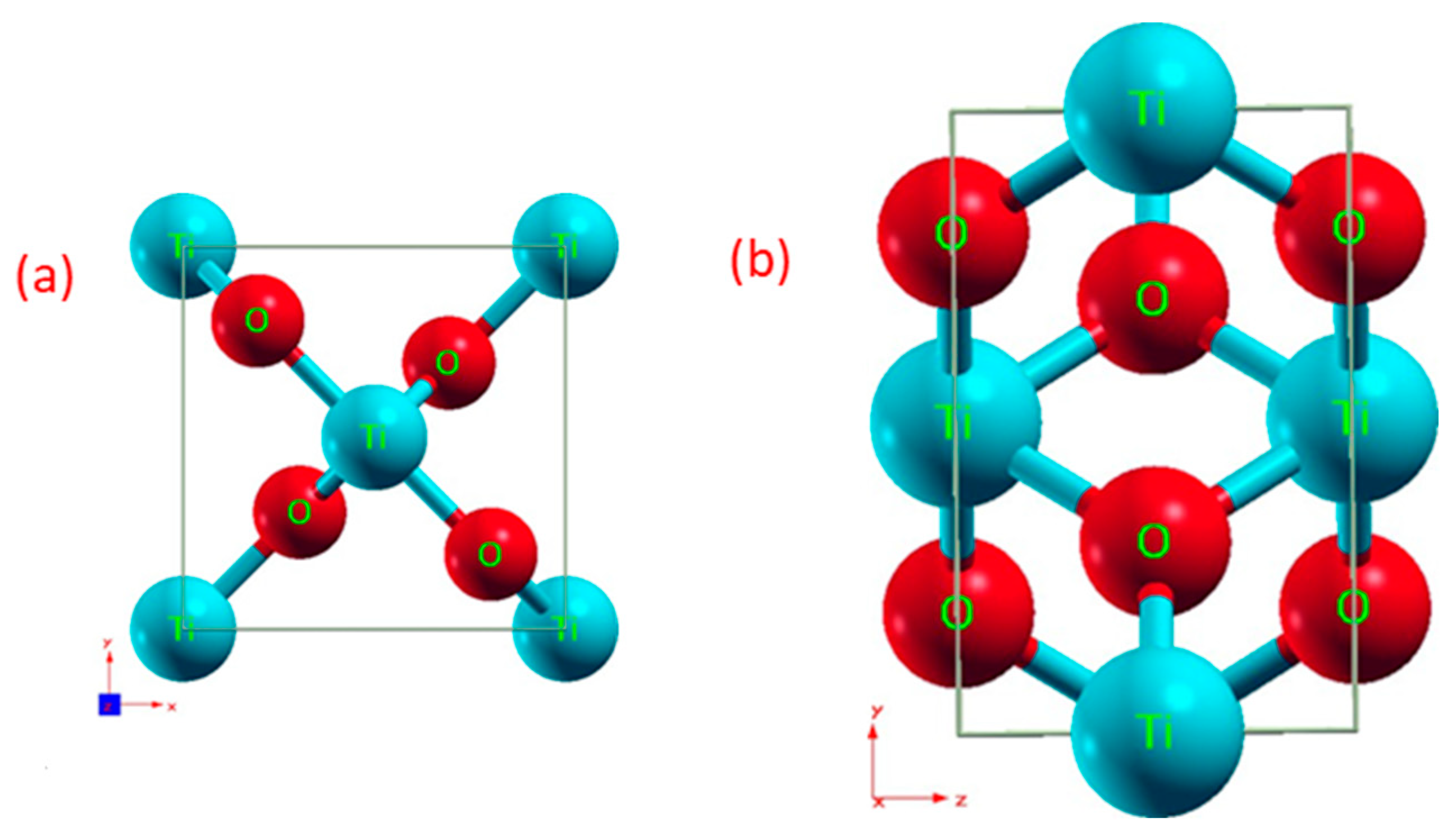

3.1. Crystal Structure

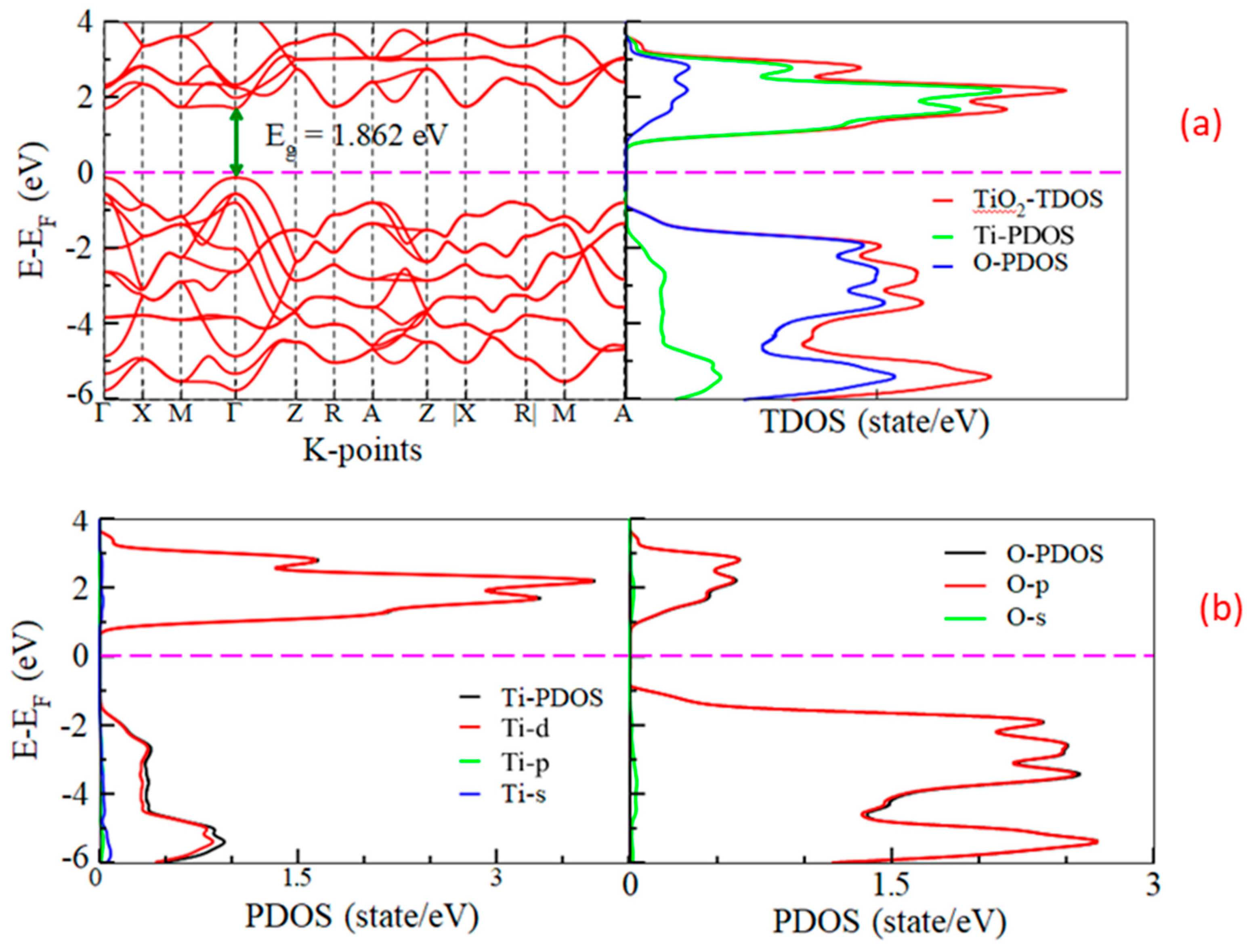

3.2. Band Gaps and Density of States

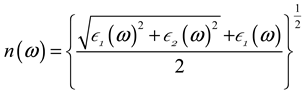

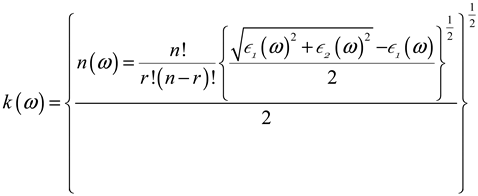

3.3. Optical Characteristics

4. Conclusions

References

- M.A. Gatou, A. Syrrakou, N. Lagopati, E. A. Pavlatou, Photocatalytic TiO2-based nanostructures as a promising material for diverse environ- mental applications: a review, Reactions 5 (2024) 135–194. [CrossRef]

- N. H. S. Suhaimi, R. Azhar, N. S. Adzis, M. A. M. Ishak, M. Z. Ramli, M. Y. Hamzah, K. Ismail, W. I. Nawawi, Recent updates on TiO2-based materials for various photocatalytic applications in environmental reme- diation and energy production, Desalination and Water Treatment (2024) 100976. [CrossRef]

- K. Fukuda, I. Fujii, R. Kitoh, I. Awai, Molecular dynamics study of the TiO2 (rutile) and TiO2-ZrO2 systems, Acta Crystallographica Section B: Structural Science 49 (1993) 781–783.

- A. Thilagam, D. Simpson, A. Gerson, A first-principles study of the dielectric properties of TiO polymorphs, Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 23 (2010) 025901. [CrossRef]

- Thilagam, A., Simpson, D.J. and Gerson, A.R., 2010. A first-principles study of the dielectric properties of TiO2 polymorphs. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 23(2), p.025901. [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K., Fujii, I., Kitoh, R. and Awai, I., 1993. Molecular dynamics study of the TiO2 (rutile) and TiO2-ZrO2 systems. Structural Science, 49 (4), pp.781-783.

- Gatou, M.A., Syrrakou, A., Lagopati, N. and Pavlatou, E.A., 2024. Photocatalytic TiO2-based nanostructures as a promising material for diverse environmental applications: a review. Reactions, 5(1), pp.135-194. [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, N.H.S., Azhar, R., Adzis, N.S., Ishak, M.A.M., Ramli, M.Z., Hamzah, M.Y., Ismail, K. and Nawawi, W.I., 2025. Recent updates on TiO2-based materials for various photocatalytic applications in environmental remediation and energy production. Desalination and Water Treatment, 321, p.100976. [CrossRef]

- Dong, J. and Drabold, D.A., 1998. Atomistic structure of band-tail states in amorphous silicon. Physical review letters, 80(9), p.1928. [CrossRef]

- Valencia S, Marn J M, Restrepo G. Study of the bandgap of synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles using the sol-gel method and a hydrothermal treatment. Open Mater. Sci. 2010; 4: 9. [CrossRef]

- Cai B, Drabold D A. Properties of amorphous GaN from first-principles simulations. Phy. Rev. B 2011; 84: 075216. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J., 2008. Physics of amorphous conducting oxides. Journal of non-crystalline solids, 354(19-25), pp.2791-2795. [CrossRef]

- Manzini I, Antanioli G, Bersani D, Lottici P P, Gnappi G, and Montonero A, X-ray absorption spectroscopy study of crystallization processes in sol-gel-derived TiO2. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1995; 519:192. [CrossRef]

- Shao G. Electronic structures of manganese-doped rutile TiO2 from first principles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008; 112:18677. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C., Ghosez, P. and Gonze, X., 1994. Lattice dynamics and dielectric properties of incipient ferroelectric TiO2 rutile. Physical Review B, 50(18), p.13379.

- Lide, D.R. ed., 2004. CRC handbook of chemistry and physics (Vol. 85). CRC press.

- Perdew, J.P., Burke, K. and Ernzerhof, M., 1996. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Physical review letters, 77(18), p.3865. [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P., Baroni, S., Bonini, N., Calandra, M., Car, R., Cavazzoni, C., Ceresoli, D., Chiarotti, G.L., Cococcioni, M., Dabo, I. and Dal Corso, A., 2009. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantumsimulations of materials. Journal of physics: Condensed matter, 21(39), p.395502.

- Matsui, M. and Akaogi, M., 1991. Molecular dynamics simulation of the structural and physical properties of the four polymorphs of TiO2. Molecular Simulation, 6(4-6), pp.239-244. [CrossRef]

- Nowotny J. Titanium dioxide-based semiconductors for solar-driven environmentally friendly applications: impact of point defects on performance; Energy Environ. Sci. 2008; 2:565. [CrossRef]

- Ollis D F, Al-Ekabi H.Photocatalytic purification and treatment of water and air. Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands 1993.

- Gratzel M. Mesoporous oxide junctions and nanostructured solar cells. Curr.Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 1999; 4:314. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y Q, Chen S G, Tang X H, Palchik O, Zaban A, Koltypin Y, Gedanken A. mesoporous titanium dioxide: sono-chemical synthesis and application in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2001; 11:521.

- Rahman M, MacElroy D, Dowling D P. Influence of the physical, structural and chemical properties on the photoresponse property of magnetron sputtered TiO2 for the application of water splitting. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2011; 11, 8642. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).