1. Introduction

Complicated intra-abdominal infections are the second leading cause of sepsis-related mortality and they are a significant challenge for physicians, accounting for nearly 60% of all surgical patients with sepsis. Treatment focuses on effective intra-abdominal source control and appropriate antimicrobial therapy to reduce mortality. However, despite prevention, advancements in diagnosis and treatment, mortality rates remain high, ranging from 20% to 60% [

1].

Intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC), with or without associated candidemia, is caused by overgrowth of

Candida spp. in the abdominal cavity (see

Table 1). Its incidence has increased in recent decades, ranging from 7-70% depending on the main cause (perforation of the upper digestive tract 41%, above the angle of Treitz to those originating in the lower digestive tract 12%). IAC mainly affects critically ill patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, especially those with complex surgical cases or immunocompromised individuals [

2,

3,

4].

Candida spp. is part of the normal endogenous microbiota in 40–50% of humans, with its growth usually controlled by microbiome diversity and host conditions. Patients in intensive care units (ICU) are at the highest risk of invasive candidiasis [

5]. Upon ICU admission, there is a rapid colonization of mucocutaneous surfaces, which increases the risk of candidemia, with a mortality rate of up to 45%. Disruptions caused by surgery, antibiotics, immunosuppression, or intestinal mucosal injuries (e.g. perforation) can lead to

Candida spp. invasion and dissemination in the abdominal cavity [

6].

This review provides updates on key concepts regarding the epidemiology and impact of Candida spp. in the peritoneal cavity, as well as risk factors for managing patients with intra-abdominal complications. Finally, it discusses antifungal treatment strategies based on pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) parameters and antifungal susceptibility to develop an empirical treatment algorithm tailored to clinical realities.

Table 1.

Classification of Intra-abdominal Candidiasis (IAC) Types (modified from reference 8).

Table 1.

Classification of Intra-abdominal Candidiasis (IAC) Types (modified from reference 8).

| Primary Peritonitis |

Peritoneal inflammation associated with the isolation of Candida spp. in the absence of gastrointestinal perforation or any other visceral process that justifies it. |

| Secondary Peritonitis |

Peritoneal infection by Candida spp. because of a pathological process or gastrointestinal perforation. |

| Intra-abdominal Abscess of Gastrointestinal Origin |

Isolation of Candida spp. in a collection of purulent material arising from secondary peritonitis. |

| Secondary Peritonitis of Hepatobiliary or Pancreatic Origin |

Peritoneal infection by Candida spp. resulting from a pathological process of the liver, gallbladder, bile ducts, or pancreas.la vesícula biliar, los conductos biliares o hepáticos, o el páncreas. |

| Intra-abdominal Abscess of Hepatobiliary or Pancreatic Origin |

Abscess with isolation of Candida spp. resulting from a pathological process of the liver, gallbladder, bile ducts, or pancreas. Infected bilomas, pancreatic pseudocysts, or other (peri)pancreatic collections are also classified as abscesses. |

| Infected Pancreatic Necrosis |

Isolation of Candida spp. in non-viable pancreatic tissue as a consequence of pancreatitis. |

| Cholecystitis, Cholangitis |

Isolation of Candida spp. in material from the gallbladder or biliary tract. |

| Recurrent IAC |

Isolation of Candida spp. appearing after the apparent resolution of clinical or radiological findings of an initial infection. |

| Persistent IAC |

Isolation of Candida spp. in a new intra-abdominal sample 48 hours after adequate source control and appropriate antifungal treatment. |

2. Epidemiology

Invasive candidiasis cases are predominantly caused by five

Candida species:

C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and

C. krusei. The most prevalent

Candida species identified in peritoneal cavity samples are

C. albicans, C. glabrata, and

C. tropicalis. However, recent decades have seen a notable epidemiological shift, with an increase in non-albicans

Candida species and the emergence of species demonstrating reduced sensitivity to commonly used antifungal agents. Regarding IAC, Dupont H et al. analysed samples from patients with peritonitis admitted to the ICU, of whom 30.6% had

Candida spp. Peritonitis [

7]. The most frequently isolated species in these cases was

C. albicans (74%), followed by

C. glabrata (17%). Vergidis P et al. identified 163 IAC cases and 161 candidemias among more than 34,000 patients, with a rate of 4.7 episodes per 1,000 admissions. A notable finding, which has gained increased attention, is the co-infection by two

Candida species, observed in 10% of the study participants [

8]. A multicentre study (EUCANDICU), conducted in 23 ICUs across nine European countries, analyzed 570 episodes of invasive candidiasis (7 episodes per 1,000 ICU admissions). Of these cases, 65% were candidemia, 29% were IAC, and 5% were IAC in combination with candidemia. A noteworthy finding of this study is that 43% of cases involved non-albicans

Candida species, with an 8% rate of co-infection by two species [

2].

Of particular note is a relatively new species,

Candida auris, which has become a global health concern. Since it was first identified in Japan (2009), it has spread rapidly to more than 35 countries [

9]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has classified

C. auris as a critical priority pathogen on its fungal priority list. The significance of

C. auris lies in its high resistance to antifungal agents, which severely limits therapeutic options. In addition, the challenges associated with its laboratory identification, combined with its ease of transmission, provide ideal conditions for epidemic outbreaks. Furthermore,

C. auris can persist in the environment for weeks, and the lack of effective decolonization methods makes controlling it spread a major challenge. As is evident, the epidemiology of both candidemia and IAC has shifted towards non-albicans

Candida species. The reasons for this shift are thought to be linked to the increasing use of azoles for "prophylactic" purposes, as well as the rise in gastrointestinal pathology among older patients with more comorbidities. These findings should be carefully considered when determining the empirical treatment for these patients.

3. Risk Factors

As outlined in various publications by different authors, there are different risk factors associated with the likelihood of invasive candidiasis [

1,

2,

6].

Table 2 presents the most common risk factors. Prior colonization, especially multifocal colonization, is a crucial factor that should be assessed in critically ill patients, as it plays a key role in diagnosing or predicting IAC using various scoring systems. Another vital factor is prior antibiotic treatment, which is considered a significant risk factor for IAC in nearly all studies. It is important to note that approximately 60% of ICU patients receive antibiotic treatment for various reasons [

10], which significantly increases the number of patients at potential risk for IAC. Finally, the widespread overuse of fluconazole for preventive or prophylactic purposes exerts selective pressure not only on

Candida spp. but also markedly contributes to their resistance to azoles.

Research has identified comparable risk factors for IAC. Bassetti et al. published a study on predictive factors for IAC in ICU patients, using a logistic regression analysis from the EUCANDICU study [

11]. The authors observed that recurrent gastrointestinal perforation (OR = 13.9, 95% CI 2.6–72.8), anastomotic leakage (OR = 6.6, 95% CI 1.9–21.9), intra-abdominal drains (OR = 6.5, 95% CI 1.7–25.0), receiving antifungal treatment (OR = 4.2, 95% CI 1.04–17.4), or antibiotic treatment for more than seven days (OR = 3.7, 95% CI 1.3–10.5) were independent predictors. As Bassetti et al. highlighted in another multicentre study involving more than 300 cases of candidemia, intra-abdominal infection increases the risk of developing shock (OR = 2.18, 95% CI 1.04–4.55) [

12].

Finally, Dupont H et al. used a multivariate model to assess whether the presence of

Candida spp. could be predicted in critically ill patients with peritonitis. The authors found that a high gastrointestinal origin (above the Treitz ligament) increased the risk of

Candida isolation by 2.4 times (OR = 2.38), as did antibiotic administration (OR = 2.25) and the presence of shock (OR = 2.45) [

7].

As antibiotic treatment is mandatory in patients with peritonitis, it remains a non-modifiable risk factor. However, it should be specifically considered when deciding whether to initiate antifungal therapy. Furthermore, as will be discussed later, in more than 40% of cases, bacterial and fungal infections coexist, and this association appears to have a significant impact on patient mortality [

13,

14].

Table 2.

Risk factors for invasive candidiasis in non-neutropenic adults, children, and neonates.

Table 2.

Risk factors for invasive candidiasis in non-neutropenic adults, children, and neonates.

| Adults |

| 1.- Multifocal colonization |

| 2.- Use of antibiotics |

| 3.- Use of antifungals |

| 4.- Renal failure |

| 5.- Severe pancreatitis |

| 6.- Prolonged ICU stay |

| 7.- High disease severity |

| 8.- Hemodyalisis |

| 9.- Presence of a central venous catheter |

| 10.- Mechanical ventilation |

| 11.- Abdominal surgical procedures |

| 12.- Use of corticosteroids |

| 13.- Parenteral nutrition |

| 14.- Diabetes |

| Newborn and Children |

| 1.- Prematurity |

| 2.- Low birth weight |

| 3.- Low APGAR score (American Pediatric Gross Assessment) |

| 4.- Congenital disease |

4. Diagnosis

The isolation of

Candida spp. in blood (candidemia) or other sterile body fluids is a clear criterion for infection. However, the diagnostic significance of its isolation in respiratory samples (which has no significance except in immunocompromised patients) or in samples obtained by puncture/surgery (especially those obtained from abdominal drains, which are potentially contaminated) remains a subject of controversy. The initial diagnostic approach involves the identification of patients with the previously mentioned risk factors. Secondly, it is essential to obtain intra or perioperative samples (fluid or tissue), as well as any other clinically relevant samples. Surveillance cultures also play an important role in diagnosis by demonstrating multiple colonization (

Table 3). Additionally, predictive scores (see Table 4) can be applied to patients with more than two weeks of ICU stay, allowing us to assess the risk probability of invasive candidiasis. Thirdly, serological determinations of different biomarkers are also considered.

The gold standard for diagnosing invasive candidiasis is blood culture, although this method has significant limitations. Its sensitivity ranges from 50% to 75%, and the time required from sample collection to fungal identification is at least 48-72 hours. This is particularly problematic because yeast replication is often slower than bacterial replication, leading to delayed blood culture positivity. Once a blood culture has returned a positive result, further identification is required. [

15,

16]

Table 3.

Different diagnostic techniques for invasive candidiasis.

Table 3.

Different diagnostic techniques for invasive candidiasis.

| Methods |

Coments |

| Detection of Mannan Antigen (M-Ag) and Anti-Mannan Antibody (M-Ac) |

The combined detection of antigen and antibody is recommended for all patients suspected of invasive candidiasis. It has a high negative predictive value of 85-95%. |

| Detection and quantification of anti-mycelial or anti-germ tube antibodies (CAGTA) |

This technique has a sensitivity of 84.4% and a specificity of 94.7% for diagnosing invasive candidiasis when antibody titers exceed 1:160. Additionally, it may help distinguish between transient or catheter-related candidemia (CAGTA–) and deep-seated infection-associated candidemia (CAGTA+). |

| Determination of 1,3-ß-D-glucan |

1,3-ß-D-glucan is a fungal cell wall component released during infection. It is a nonspecific biomarker and does not identify the causative species. It has demonstrated usefulness in diagnosing invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients, with a high negative predictive value (>90%), making it valuable for ruling out infection or discontinuing antifungal treatment. |

| In situ hybridization PNA-FISH Yeast Traffic Light |

This technique uses species-specific peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes that hybridize in situ with the target DNA of various Candida species, producing fluorescence in different colors. It also allows the identification of fluconazole-sensitive species, facilitating treatment adjustments and potential de-escalation. It is a simple and rapid technique with a sensitivity of 92-100% and a specificity of 95-100%. |

| Mass spectrometry with soft ionization (MALDI-TOF) |

This technique is performed on a positive blood culture. It identifies bacteria and fungi through proteomic analysis, allowing accurate identification of fungal isolates in solid culture media in less than 30 minutes. |

| Detection of nucleic acids via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) |

This technique enables the detection of bacterial DNA and certain Candida species in blood or sterile fluids using real-time multiplex PCR or microarrays. The limitation is that it requires a positive blood culture, but it allows rapid detection (1 hour) and resistance gene determination, which can help tailor treatment. |

| T2 Rm (Candida panel) |

This technique detects Candida spp. using magnetic resonance within 3-5 hours. Its advantage is that it is performed on whole blood without incubation and can detect low yeast concentrations (1-3 CFU/mL). |

Table 4.

Predictive Scales for Invasive Candidiasis Used in Clinical Practice.

Table 4.

Predictive Scales for Invasive Candidiasis Used in Clinical Practice.

| Scale |

Variables |

Cutoff point |

Sensitivity/Specificity |

Comments |

| Pittet Colonization Index |

Ratio of the number of colonized sites to the number of cultured sites. |

> 0,5 |

100% / 69% |

In surgical patients, it requires quantitative cultures from all sites, which increases cost and microbiology processing time. |

| Corrected Pittet Colonization Index |

Ratio of the number of sites with high colonization (>10^5 CFU) to the number of cultured sites |

> 0,4 |

100% / 100% |

Similar to the previous index. |

|

Candida score |

Multifocal colonization (1 point)

Abdominal surgery (1 point)

Parenteral nutrition (1 point)

Severe sepsis – Shock (2 points) |

> 3 |

77% /66% |

More practical for ICU patients with >7 days of stay. Note that within the cutoff point of 3, multifocal colonization is mandatory. |

| Nebraska Rule |

Stay >4 days in ICU +

|

2,45 |

84% / 60% |

More complex to implement as it requires performing a regression calculation with coefficients of the different risk factors. |

4.1. Biomarkers for Diagnosing Invasive Candidiasis

León C et al. evaluated the usefulness of different biomarkers in critically ill patients with intra-abdominal pathology, both individually and in combination. The study’s key findings included the positive results for 1,3-ß-D-glucan (BDG) and anti-mycelial or anti-germ tube antibodies (CAGTA) in a single sample, or at least one of them in two consecutive samples, was identified as the most effective strategy for diagnosing invasive candidiasis (IC). In contrast, the individual or combined positivity of C-PCR, mannan antigen (M-Ag), and anti-mannan antibody (M-Ac) was found to have minimal value in distinguishing IC from colonization. The authors concluded that BDG is the most suitable biomarker for diagnosing IC in critically ill patients with acute abdominal complications. Its diagnostic performance is enhanced when combined with CAGTA [

17]. However, it should be noted that other studies have not consistently replicated these findings.

Currently, most researchers agree that, among all biomarkers, BDG is the most widely implemented in daily practice. Rather than using it solely for diagnosing invasive candidiasis, it is often recommended for stopping or withdrawing antifungal treatment in patients with a high suspicion of infection, given its high negative predictive value.

4.2. Predictive Scores for Invasive Candidiasis

Several researchers have attempted to develop the most effective predictive scores to assess the risk of invasive candidiasis in patients with risk factors. Table 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the main predictive scores, their characteristics, and limitations. One of the earliest predictive scales was the Pittet colonization index [

18], which was designed for surgical patients. While it is a useful tool, it requires quantitative cultures, which can put a strain on microbiology services. This study demonstrated that a corrected colonization index greater than 0.4 had a up to 100% positive and negative predictive value. León C et al. conducted a prospective study involving 1,720 critically ill patients with an ICU stay of over 7 days, leading to the development of the "

Candida score" or "Sevilla Score". A score greater than 2.5 was able to predict

Candida infection with 81% sensitivity and 74% specificity [

19]. This score was validated in a subsequent prospective study of 1,107 critically ill, non-neutropenic patients, confirming that a

Candida score ≥3 was useful for distinguishing infection. Its diagnostic accuracy was superior to the Pittet colonization index. It is important to highlight that prior colonization by

Candida spp. is a mandatory criterion for a

Candida score >3 [

20].

As discussed later, different authors have implemented these scales to enable early treatment, observing a decrease in the incidence of invasive candidiasis, though often not significant, with no impact on mortality. From our perspective, patients with a prolonged ICU stay, risk factors, and a Candida score >3 should be considered to have a high suspicion of invasive candidiasis (provided multifocal colonization is present) and should begin antifungal treatment early. In these patients, with a high pre-test probability of invasive candidiasis, and if available, it would be appropriate to implement molecular diagnostic techniques or biomarker determination (BDG) to refine the diagnosis and avoid the overuse of antifungals.

5. Mortality

The mortality rate for invasive candidiasis is high, ranging from 40% to 60% according to various authors [

3,

6,

21]. The mortality rate for transient candidemia (e.g., secondary to catheter use) is significantly lower than that for candidemia caused by a deep focus (e.g., endocarditis, intra-abdominal infections). Researchers have explored the impact of early antifungal treatment (see below) and have not observed a favorable effect on mortality in patients with invasive candidiasis. It is crucial to consider three key factors in the pathogenesis of this condition to understand its high mortality. Firstly, a high fungal load may be a result of broad-spectrum antibiotic use, especially anti-anaerobic antimicrobials. This elevated load or colonization facilitates the translocation of the yeast from the gastrointestinal tract in patients who commonly suffer from prolonged ileus and severe intestinal microcirculation alterations. Secondly, the disruption of the integrity of both the cutaneous-mucosal barrier (candidemia) and the gastrointestinal tract (intra-abdominal candidiasis) must be considered, whether due to spontaneous perforations or prolonged use of drains or chronic inflammatory processes (e.g. pancreatitis). Finally, the third element is the dysfunction of immunity that every critically ill, non-neutropenic patient experiences, leading to dissemination to deep tissues [

23]. In this context, it is important to note that tertiary peritonitis has a poor prognosis beyond treatment due to immune dysfunction in the peritoneum, which hinders the resolution of the infectious process.

Despite acknowledging these factors, the positive impact of appropriate antifungal treatment is indisputable. In the initial study by Morrel L et al., early treatment (within 12 hours) was associated with a significant reduction in mortality (12%) compared to late treatment (>12 hours), which had a 30% mortality rate in patients with candidemia (24). This finding has been replicated by other researchers [

24,

25]. In their multivariate analysis, Morrel L et al. found that treatment delay was associated with twice the risk of death (OR=2.06). In the same study, prior antibiotic administration was found to be associated with a higher mortality (OR=4.06). Garey K et al. found that fluconazole treatment in patients with candidemia was associated with lower mortality (15%) when administered on day 1 (mortality 23%), day 2 (mortality 37%), or day 3 (mortality 42%) after blood culture. These authors reported a 1.5 higher risk of mortality (OR=1.52) for each day of treatment delay [

25]. Finally, Zilberberg MD et al. reported a higher mortality rate (28.9%, p=0.056) in patients with candidemia who received inappropriate treatment. It is noteworthy that in this study, mortality was 0% in patients with appropriate treatment [

26].

In an observational, prospective, multicentre study in critically ill patients with community-acquired intra-abdominal infection, the isolation of

Candida spp. in peritoneal samples was closely associated with mortality [

27]. Despite the introduction of new antifungals, such as echinocandins in the early 2000s, mortality in IAC remains above 50%. The shift in IAC etiology towards non-albicans species is partly responsible for this high mortality, along with increased empirical inappropriate treatment due to high resistance to commonly used antifungals. Of particular concern is the emergence of

C. auris, the first fungal pathogen classified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an urgent public health threat due to its association with extremely high mortality rates and the potential to develop resistance to all current antifungals.

Shorr A et al. [

28] and Vardakas KZ et al. [

29] conducted two meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials assessing prophylaxis with azoles in surgical ICU patients. These analyses concluded that there was a reduction in the incidence of fungal infections, although with no impact on mortality. Conversely, a meta-analysis encompassing 12 studies conducted on non-neutropenic critically ill patients determined that azole prophylaxis led to a reduction in mortality (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59-0.97) and the incidence of invasive fungal infection (RR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.31-0.68)(28,29).

At this stage in the review, we may feel uncertain, given the observed association between the administration of antibiotics and the presence of Candida spp., as well as the previously documented link between prior antibiotic use and higher mortality, particularly in cases of IAC. Consequently, the question arises as to whether it is advisable to administer antibiotics to patients with peritonitis. The answer is clear: in peritonitis, antibiotics should be administered, but we must bear in mind that this need acts as a predisposing condition for the added or coexisting fungal infection. Consequently, we will undertake an active search for fungal infection in these patients, utilizing the available resources to initiate treatment promptly. However, we must also consider that a strategy of generalized early treatment can lead to the excessive use of antifungal medication and the possible increase in resistance to azoles or to infections caused by non-albicans species.

6. Treatment

The management of complicated intra-abdominal infection is a complex scenario where other conditions, beyond antifungal treatment, play a significant role. The patient’s specific conditions, as well as early and proper control of the source of infection, are key factors in determining the outcome for these patients. Once the source of infection has been addressed, the role of antifungal therapy becomes crucial.

Several authors have used different definitions for treatments related to possible or probable Candida spp. infection in their studies. This variability complicates comparisons and limits the strength of conclusions. Therefore, in this review, we will apply the definitions presented in the 2019 guidelines of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/European Society of Infections working group (30):

1) “Prophylaxis” is antifungal treatment given without clear evidence of infection to critically ill patients at high risk of invasive candidiasis due to intrinsic factors (e.g. immunosuppression) or hospitalization-related factors (e.g, septic shock, abdominal surgery, prolonged ICU stay, broad-spectrum antibiotics);

2) “Pre-emptive therapy” is antifungal treatment of critically ill patients at high risk of invasive candidiasis guided by fungal biomarkers or risk assessment scores associated with multifocal colonization;

3) “Empirical therapy” is antifungal treatment of critically ill patients with signs and symptoms of infection (e.g., persistent fever of unknown origin) who have specific risk factors for invasive candidiasis, regardless of biomarker results; and finally,

4) “Targeted therapy” is antifungal treatment based on microbiological findings confirming the presence of Candida spp. and its susceptibility to different antifungal agents.

To ensure optimal treatment efficacy and minimize the risk of re-resistance, it is essential that the antifungal agent reach adequate concentrations at the site of infection, which in this case could be intraperitoneal. It is important to emphasize that there is limited and often conflicting information on intra-abdominal antifungal concentrations in critically ill patients with peritonitis [

31]. It is important to recognize the limitations of extrapolating data from blood concentrations to intraperitoneal levels. The central compartment, which includes the bloodstream, provides a convenient method for monitoring drug levels and assessing pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) behavior to optimize drug efficacy.

However, it is well established that patients in critical condition exhibit significant variability in drug PK due to several factors. These include a marked increase in drug distribution volume and elevated renal clearance, particularly during the initial phases of critical illness [

32]. These PK alterations primarily impact hydrophilic drugs, such as echinocandins, which are the first-line treatment recommended by various international guidelines. If the dosage of these drugs is not properly adjusted, often requiring dose escalation or loading doses, the resulting drug concentrations may fall below the levels needed to act against pathogens with reduced susceptibility, thus promoting the emergence of so-called "resistant mutants"[

33]. In cases of intra-abdominal infections, the diffusion of drugs into the peritoneal cavity is further hindered by poor penetration, as well as the presence of surgical drains (often high-output or frequently flushed). Additional factors that can impact the ability to achieve adequate drug concentrations include high body weight (over 100kg), low albumin levels common among critically ill patients, and the frequent use of intermittent or continuous renal replacement therapies [

34].

It is essential to consider all these factors when selecting the most appropriate antifungal treatment for each patient’s specific condition.

Three classes of drugs (azoles, echinocandins, and polyenes) make up the available therapeutic arsenal for treating candidiasis and IAC. As previously mentioned, Candida albicans remains the most frequently isolated species. However, the frequent presence of non-albicans species and the emergence of resistance to azoles and echinocandins make empirical treatment a significant challenge that must be addressed on a daily basis (see Table 4).

Table 4.

In vitro susceptibility of available antifungals (++ Adequate effect; -/+ Possible resistance; -- Resistance. L-AMB: liposomal amphotericin B).

Table 4.

In vitro susceptibility of available antifungals (++ Adequate effect; -/+ Possible resistance; -- Resistance. L-AMB: liposomal amphotericin B).

| Fungal species |

L-AMB |

Fluconazole |

Voriconazole |

Isavuconazole |

Equinocandins |

| Candida albicans |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

| Candida parapsilosis |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

+ |

| Candida tropicalis |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

++ |

| Candida glabrata |

++ |

-/+ |

-/+ |

-/+ |

-/+ |

| Candida krusei |

++ |

-- |

-- |

-- |

++ |

| Candida auris |

+ |

-- |

-- |

++ |

+ |

6.1. Azoles

Azoles are a class of antifungal agents that disrupt ergosterol biosynthesis in the fungal membrane by inhibiting 14-α-sterol demethylase, a microsomal cytochrome (CYP). These compounds are categorized into two main groups: imidazoles (e.g. clotrimazole, miconazole, ketoconazole) and triazoles (e.g. fluconazole, voriconazole, isavuconazole). Systemic triazoles are metabolized more slowly and have fewer effects on human sterol synthesis compared to imidazoles. All azoles undergo hepatic metabolism through different cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, albeit with varying intensities, leading to numerous drug interactions that must be carefully considered.

6.1.1. Fluconazole

The primary mechanism of action of fluconazole consists of the inhibition of fungal cytochrome P-450 by blocking 14-alpha-lanosterol demethylation, a key step in the biosynthesis of fungal ergosterol, and a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4. A direct relationship has been observed between the dose, the MIC (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) and clinical efficacy.

In addition to multiple observed drug interactions, there is a risk of increasing plasma concentrations of other compounds metabolized by CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 when co-administered with fluconazole (such as anticoagulants, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, carbamazepine, calcium channel blockers, fentanyl, sirolimus, tacrolimus, losartan, phenytoin, prednisone, etc.). Due to its long half-life, fluconazole continues to inhibit enzymes for four to five days after discontinuation [

35]. Fluconazole can be administered orally (with good bioavailability, though not widely recommended in critically ill patients) or intravenously. It is important to note that food intake does not affect oral absorption. Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) are reached between 0.5 and 1.5 hours post-dose and are proportional to the administered dose. Steady-state levels are achieved within 4 to 5 days after multiple once-daily doses. A loading dose of 200 mg on day 1, which is twice the usual daily dose, increases plasma levels to 90% of steady-state concentrations by day 2, making this a recommended strategy for critically ill patients. The volume of distribution (VD) is 40 L, with low protein binding (10%). This means that while a large proportion of the drug remains free to exert its action, its renal elimination is significantly increased in hyper-filtering patients or those undergoing renal replacement therapies, requiring reconsideration of its use in such patients. Fluconazole distributes widely, achieving high concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), lungs, skin, cornea, and urine. The recommended loading dose is 800 mg (400 mg every 12 hours) on the first day, followed by 400 mg/day. Maintenance doses may vary depending on patient conditions [

36,

37].

6.1.2. Voriconazole

The primary mechanism of action of voriconazole is the inhibition of 14-alpha-lanosterol demethylation, which is mediated by fungal cytochrome P-450. This is a key step in the process of fungal ergosterol biosynthesis. The accumulation of 14-alpha-methyl sterols is associated with the subsequent loss of ergosterol in the fungal cell membrane [

38]. Voriconazole can be administered orally (though rarely in critically ill patients) or intravenously. Its pharmacokinetics are nonlinear due to metabolic saturation, meaning that a disproportionate rise in plasma concentrations is seen with increases in dose. Administering a loading dose helps to achieve plasma concentrations close to steady-state within the first 24 hours, making this a particularly important strategy for critically ill patients. The oral bioavailability of voriconazole is 96%, however, it is influenced by CYP3A4 activity and a transporter protein, as well as by high-fat meals, which reduce Cmax and AUC (area under the curve). Voriconazole distributes widely, with a volume of distribution of 4.6 L/kg. Voriconazole has a plasma protein binding of 58%, and it reaches effective concentrations in the CSF, lungs, brain, liver, kidneys, and spleen. As previously mentioned, voriconazole is metabolized by, and also inhibits, cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4. The presence of inhibitors or inducers of these isoenzymes can result in alterations to voriconazole plasma concentrations. Voriconazole can also increase plasma concentrations of substances metabolized through these CYP450 enzymes, particularly those processed by CYP3A4, as it is a potent inhibitor of this enzyme.

This means that voriconazole exhibits significant inter-individual variability, requiring plasma drug level monitoring to ensure therapeutic effectiveness. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP enzymes (such as those found in 15-20% of the Asian population) slow drug elimination, increasing the risk of toxicity. While these polymorphisms are less prevalent in Caucasian populations (with a frequency of less than 5%), some patients exhibit rapid metabolization, which can complicate the achievement of adequate drug levels [

37].

6.1.3. Isavuconazole

Isavuconazole is a fungicide that exerts its effects by blocking ergosterol synthesis, a key component of the fungal cell membrane. This is achieved through the inhibition of cytochrome P450-dependent lanosterol 14-alpha-demethylase. This results in an accumulation of methylated sterol precursors and a reduction in ergosterol within the fungal membrane, weakening its structure and function.

Isavuconazole is administered as a prodrug that is rapidly hydrolyzed in plasma to its active form. It can be administered orally (with high bioavailability but rarely used in critically ill patients) or intravenously. Its pharmacokinetics are linear, with Cmax and AUC values proportional to the administered dose, and drug accumulation occurs with multiple dosing. Isavuconazole distributes extensively, with a high VD (>400 L). It has strong protein binding (>99%) and achieves adequate concentrations in CSF, lungs, ascitic fluid, and the eye. The drug is metabolized in the liver via CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT). While it interacts with various drugs, isavuconazole has a better safety profile than voriconazole. The drug is slowly eliminated from the body, with a half-life of 84-117 hours, likely due to its high protein binding and large distribution volume. Reduced susceptibility to triazole antifungals has been associated with mutations in the fungal CYP51A and CYP51B genes, which encode the 14-alpha-demethylase enzyme involved in ergosterol biosynthesis.

Fungal strains with in vitro susceptibility to isavuconazole have been reported, but cross-resistance with voriconazole and other triazole antifungals cannot be ruled out. The recommended regimen for isavuconazole is a loading dose of 200 mg every 8 hours for the first 48 hours (total of 6 doses), followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg once daily, starting 12-24 hours after the last loading dose. As isavuconazole does not require therapeutic drug monitoring, it is considered the most appropriate option for critically ill patients [

37,

39].

6.2. Echinocandins

6.2.1. Anidulafungin

Anidulafungin is a semi-synthetic echinocandin, a lipopeptide derived from a fermentation product of Aspergillus nidulans that is administered intravenously. It selectively inhibits 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase, preventing the formation of 1,3-β-D-glucan, an essential component of the fungal cell wall [

40]. A very low inter-individual variability in systemic exposure has been observed, and steady-state is reached the day after the loading dose is administered. The half-life is 24 hours, with a volume of distribution (Vd) of 30–50L. Anidulafungin extensively binds (>99%) to human plasma proteins. While it distributes well in the lung, no data is available on its penetration into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Its antifungal action is concentration-dependent, meaning it is associated with AUC/MIC and Cmax/MIC targets, making it crucial to ensure an adequate dose. The standard dose has been associated with a lower AUC0-24 in critically ill patients compared to healthy volunteers. Due to its extensive protein binding, only the free fraction is considered capable of diffusing into the peritoneum, potentially compromising its efficacy. While different studies suggest that peritoneal concentrations would meet the classical efficacy targets defined by an AUC/MIC of 3000 for all

Candida species, a recent study by Gioia F et al. showed that the AUC/3000 results in serum were 0.042, 0.032, and 0.022 for anidulafungin, micafungin, and caspofungin, respectively [

41]. These levels would be adequate for the treatment of

C. albicans (0.03 mg/L), but suboptimal for

C. glabrata, C. krusei, and

C. tropicalis (0.06 mg/L), potentially creating an environment conducive to resistance development.

It has been hypothesized by several authors that IAC may act as a hidden reservoir for echinocandin-resistant

Candida glabrata species.

C. glabrata, which is increasingly present in IAC, exhibits a significant and varied adaptive response to its environment, linked to intrinsic mutations in FKS genes, which encode β-1,3-D-glucan synthase. These mutations result in increased chitin content in the cell wall and paradoxical growth when high doses of echinocandins are administered. Finally, concentrations <2 mg/L lead to the selection of resistant mutants, which emerged rapidly (<48h) in laboratory studies at different echinocandin concentrations. Metabolism occurs in the plasma, with no evidence of hepatic metabolism, making anidulafungin a drug with few interactions. It undergoes slow chemical degradation at physiological temperature and pH, resulting in an open-ring peptide that lacks antifungal activity. Renal elimination is minimal (<10%).A single 200 mg loading dose should be administered on Day 1, followed by a daily maintenance dose of 100 mg [

37,

40,

41,

42].

6.2.2. Rezafungin

Rezafungin is a novel echinocandin that selectively inhibits fungal 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase with inhibition of fungal cell wall synthesis, resulting in rapid and concentration-dependent fungicidal activity in Candida species. It has state-of-the-art pharmacokinetics with remarkable stability, high solubility and an exceptionally long half-life, allowing early exposure to high drug levels. It can therefore be administered intravenously once a week, with a loading dose of 400 mg on day 1, followed by 200 mg on day 8 and once a week thereafter. [

43]. The pharmacokinetic results in the single ascending dose study were consistent with the post-first dose pharmacokinetic results in the multiple ascending dose study for each dose cohort. At all doses investigated in the single ascending dose study, mean maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) values ranged from 2.76 to 22.7 g/ml and the values corresponding to the mean area under the concentration-time curve from time zero to 168 hours (AUC0-168) ranged from 145 to 1160 g-h/ml. Both Cmax and AUC increased in a dose-proportional manner and mean half-life (t1/2) values of 80 h were observed during the first week (up to day 7) of plasma sampling (a longer terminal t1/2 of 125 to 146 h was calculated by incorporating data from later sampling times [days 14 and 21]).[

44]

Rezafungin is rapidly distributed with a volume of distribution similar to that of body water (≈40 l) and binds to 97% of plasma proteins [

45]. Like the other echinocandins, it is not affected by intermittent/continuous renal replacement techniques. Furthermore, it undergoes little or no biotransformation and is mainly excreted in the faeces, with less than 1% of the drug being excreted in the urine [

45], with an average plasma half-life of 127 to 146 hours.

Rezafungin has a broad spectrum of activity against

Candida and

Aspergillus species, including

Candida auris and subsets of fungal strains resistant to other antifungals (echinocandins and azoles), and has demonstrated therapeutic and prophylactic efficacy in animal models of candidiasis, aspergillosis and Pneumocystis pneumonia. Rezafungin has demonstrated safety and tolerability comparable to current echinocandins. In addition, rezafungin has demonstrated chemical and metabolic stability and non-hepatotoxicity compared to anidulafungin [

46,

47] with increased biofilm activity.

In phase III trials, rezafungin has demonstrated non-inferiority to caspofungin for the treatment of invasive candidiasis (ReSTORE trial) [

48] In addition to its weekly dosing, rezafungin offers other potential pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic advantages, such as excellent penetration into anatomically challenging sites, such as intra-abdominal collections, and a potentially lower risk of promoting local resistance. This positions it as a promising option for deep infections, particularly intra-abdominal infections, justifying its commercialization and inclusion as a first-line agent in recent guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis [

49].

6.3. Polyenes

6.3.1. Amphotericin B (AMB)

Liposomal amphotericin B (L-AMB) is a heptane-derived macrolide that contains seven conjugated trans double bonds and 3-amino-3-6-dideoxy-mannose (mycosamine) linked to the main ring via a glycosidic bond. The amphoteric behavior that gives the drug its name is due to the presence of a carboxyl group on the main ring and a primary amino group on mycosamine, which confer aqueous solubility at pH extremes. Its effectiveness as a fungicide or fungistatic depends on the achieved concentration and the specific fungal species. Its mechanism of action involves binding to ergosterol in the fungal membrane, leading to membrane disruption and increased permeability. Its antifungal activity is concentration-dependent, meaning it is related to the plasma concentration (Cmax) over the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), demonstrating a prolonged post-antifungal effect.

L-AMB achieves higher plasma concentrations (Cmax) than AMB and has a longer exposure time (AUC0-24). Following administration, L-AMB reaches steady-state rapidly, generally within the first four days of the same dose. A key feature of L-AMB is its action against biofilm formation, which is directly implicated in IAC [

50]. The pharmacokinetics of L-AMB are largely dependent on the composition and size of the liposomal or lipid complex particles. Large structures, such as the lipid complex (Abelcet), are rapidly absorbed by the mononuclear phagocyte system, whereas smaller liposomes remain in circulation for extended periods. AMB molecules are stabilized by phospholipids and cholesterol within the liposomal bilayer, reducing the level of toxicity to animal cells. The small size of liposomal particles (100 nm or less) ensures that drug levels remain elevated in the bloodstream, reducing distribution to organs, including the kidneys, and contributing to improved safety and reduced nephrotoxicity [

51,52].

The enhanced vascular permeability in critically ill patients has been shown to increase the transfer of L-AMB from the circulation to the lesions, thereby boosting its antifungal activity.In plasma, AMB remains associated with liposomes (97% at 4 hours, 55% at 168 hours) after L-AMB administration. It is assumed that L-AMB does not directly bind to target cells but instead facilitates AMB transfer from the liposomal membrane to the fungal cell membrane, which is critical for antifungal activity.The usual dose is 3–5 mg/kg/day, achieving adequate concentrations in the lungs, ascitic fluid, and muscle tissue. While the drug does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB) efficiently, it is indicated for use in cases of inflammation, potentially in combination with other antifungals. Finally, due to its pharmacokinetics, plasma level monitoring is not required, as its efficacy does not correlate with observed blood levels [53].

7. When and How to Treat? The Role of Guidelines

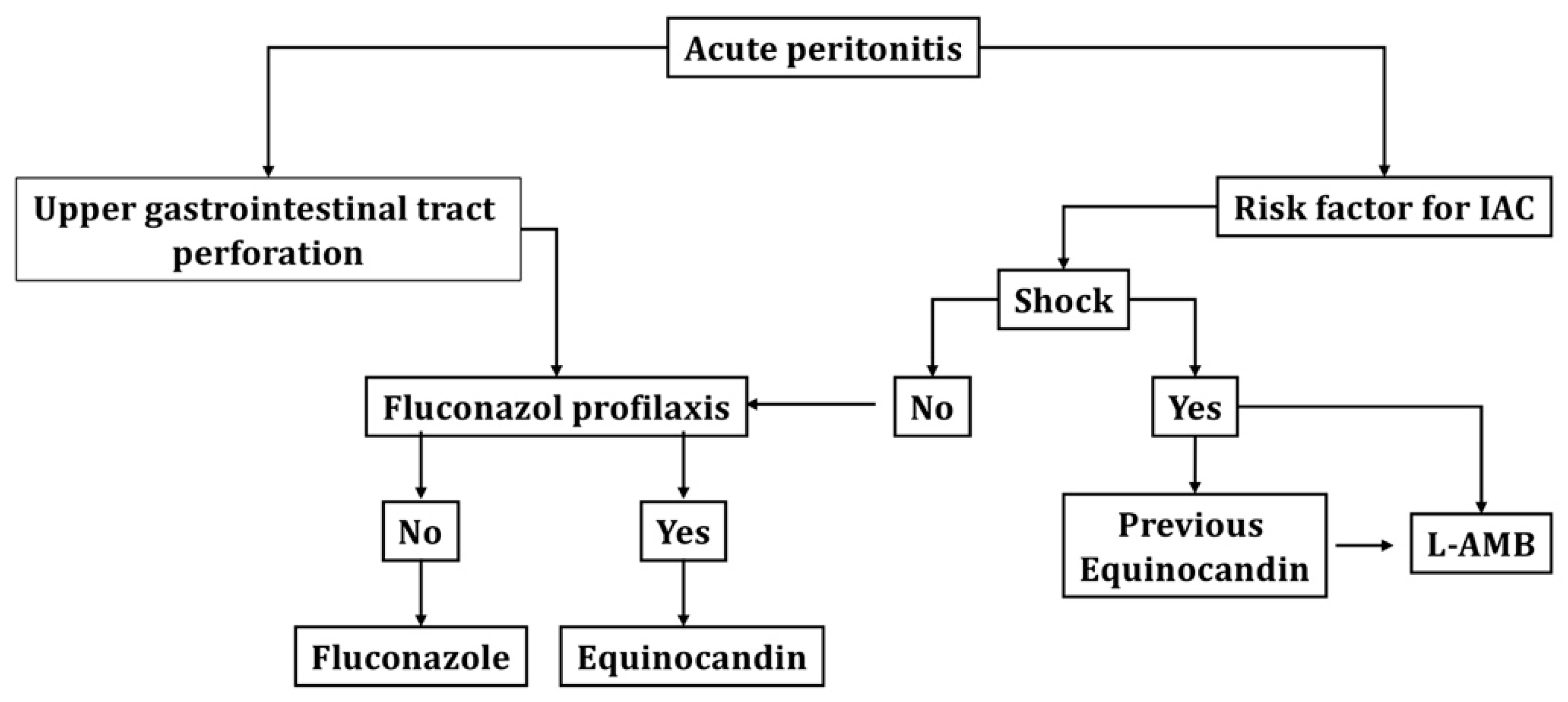

The first question to consider is When should I start empirical treatment for my patient? As previously discussed, the decision to initiate prophylactic, anticipatory, or empirical treatment will depend on the clinical conditions and risk factors of the patient. While most authors advocate against the routine use of antifungal prophylaxis in critically ill patients, we generally support the initiation of prophylactic treatment in patients with peritonitis and perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract (above the Treitz angle), particularly in patients who use antacids and have gastric neoplasms. Conversely, in patients with risk factors and positive biomarkers (BDG), we may initiate anticipatory treatment, though this approach is subject to greater controversy, particularly regarding the cost-effectiveness of biomarkers for diagnosis. Finally, in high-risk patients with fever or shock and an unclear diagnosis, initiating empirical treatment may be a consideration.

The second question pertains to

the most appropriate treatment approach. As outlined in the objectives, the purpose of this review is to provide readers with the tools to understand different aspects of invasive candidiasis and IAC, as well as the PK/PD characteristics of various antifungals. This will empower each physician to develop an empirical treatment protocol for patients at risk of invasive candidiasis/IAC, tailored to the local situation and available resources. However, it is essential to review the international guidelines, which aim to serve as a basis for our local adaptation of treatment. As outlined in

Table 5, the main guidelines provide treatment recommendations. Echinocandins are the most frequently mentioned drugs as first-line treatment for invasive candidiasis, and no specific recommendations are made for IAC, with the same treatment being accepted. However, as discussed previously, especially in cases where

C. glabrata is suspected, this may not be the most suitable option. A recent systematic review has concluded that there are no significant differences in clinical efficacy between treatment with L-AMB, echinocandins, or voriconazole in critically ill patients with invasive candidiasis. Therefore, the authors suggest that these three types of drugs should be considered for first-line treatment, and the definitive drug should be chosen based on the isolated species and the susceptibility profile. The use of L-AMB as first-line treatment is supported by various authors, based on the low likelihood of resistance development, especially in patients with a history of prior azole use. Conversely, fluconazole may not be the optimal choice for empirical treatment in patients at risk of invasive candidiasis or IAC due to the high frequency of resistance observed in non-albicans species. Therefore, as is standard practice with antibiotic treatment, an empirical broad-spectrum treatment should be initiated and then de-escalated once microbiological results confirm the species’ susceptibility to fluconazole.

Finally, in

Figure 1, we propose an algorithm for the treatment of patients with IAC that can serve as a basis for local adaptation, in relation to the epidemiology and particular resources of each unit.

8. Conclusions

Candidemia and intra-abdominal candidiasis are relatively common complications in critically ill patients. Both conditions are associated with significant morbidity and mortality due to several factors, particularly challenges in diagnosis and the increasing development of resistance to antifungal drugs. Early suspicion of these conditions is critical for prompt treatment. Screening for multiple Candida spp. colonization, using prediction scales, measuring various infection biomarkers and recognizing risk factors can facilitate timely and appropriate treatment. Empirical treatment should take into account the patient’s clinical condition, previous antifungal use, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties of available antifungals and local epidemiological susceptibility patterns.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, MMP,AR,RZ,FFGB and IML; methodology, MMP,AR,FFGB ; investigation, MMP,RZ,IML,FFGB, and AR.; writing—original draft preparation, MMP,AR ; writing—review and editing, MMP,RZ,IML,FFGB and AR; funding acquisition, AR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This study was supported with protected research time (AR) by a grant from the Ricardo Barri Casanovas Foundation (FRBC01/2024). The sponsors were not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or report writing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IAC |

Intra-abdominal candidiasis |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Maseda E, Martín-Loeches I, Zaragoza R, Pemán J, Fortún J, Grau S, Aguilar G, Varela M, Borges M, Giménez MJ, Rodríguez A. Critical appraisal beyond clinical guidelines for intraabdominal candidiasis. Crit Care. 2023 Oct 3;27(1):382. PMID: 37789338; PMCID: PMC10546659. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti M, Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, et al. Incidence and outcome of invasive candidiasis in intensive care units (ICUs) in Europe: results of the EUCANDICU project. Critical Care (London, England). 2019 Jun;23(1):219. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-019-2497-3. PMID: 31200780; PMCID: PMC6567430.

- Zaragoza R, Ramírez P, Borges M, Pemán J. Puesta al día en la candidiasis invasora en el paciente crítico no neutropénico [Update on invasive candidiasis in non-neutropenic critically ill adult patients]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016 Jul-Sep;33(3):145-51. Spanish. Epub 2016 Jul 6. PMID: 27395022. [CrossRef]

- Candel FJ, Pazos Pacheco C, Ruiz-Camps I, Maseda E, Sánchez-Benito MR, Montero A, Puig M, Gilsanz F, Aguilar J, Matesanz M. Update on management of invasive candidiasis. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2017 Dec;30(6):397-406. Epub 2017 Nov 6. PMID: 29115366.

- Krause R, Halwachs B, Thallinger GG, Klymiuk I, Gorkiewicz G, Hoenigl M, Prattes J, Valentin T, Heidrich K, Buzina W, Salzer HJ, Rabensteiner J, Prüller F, Raggam RB, Meinitzer A, Moissl-Eichinger C, Högenauer C, Quehenberger F, Kashofer K, Zollner-Schwetz I. Characterisation of Candida within the Mycobiome/Microbiome of the Lower Respiratory Tract of ICU Patients. PLoS One. 2016 May 20;11(5):e0155033. PMID: 27206014; PMCID: PMC4874575. [CrossRef]

- Bonomo RA, Chow AW, Edwards MS, Humphries R, Tamma PD, Abrahamian FM, Bessesen M, Dellinger EP, Goldstein E, Hayden MK, Kaye KS, Potoski BA, Rodríguez-Baño J, Sawyer R, Skalweit M, Snydman DR, Pahlke S, Donnelly K, Loveless J. 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America on Complicated Intra-abdominal Infections: Risk Assessment, Diagnostic Imaging, and Microbiological Evaluation in Adults, Children, and Pregnant People. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 4;79(Supplement_3):S81-S87. PMID: 38965057. [CrossRef]

- Dupont H, Paugam-Burtz C, Muller-Serieys C, Fierobe L, Chosidow D, Marmuse JP, Mantz J, Desmonts JM. Predictive factors of mortality due to polymicrobial peritonitis with Candida isolation in peritoneal fluid in critically ill patients. Arch Surg. 2002 Dec;137(12):1341-6; discussion 1347. PMID: 12470095. [CrossRef]

- Vergidis P, Clancy CJ, Shields RK, Park SY, Wildfeuer BN, Simmons RL, Nguyen MH. Intra-Abdominal Candidiasis: The Importance of Early Source Control and Antifungal Treatment. PLoS One. 2016 Apr 28;11(4):e0153247. PMID: 27123857; PMCID: PMC4849645. [CrossRef]

- García CS, Palop NT, Bayona JVM, García MM, Rodríguez DN, Álvarez MB, Serrano MDRG, Cardona CG. Candida auris: report of an outbreak. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020 Jan;38 Suppl 1:39-44. English, Spanish. PMID: 32111364. [CrossRef]

- Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron. (s.f.). ENVIN-HELICS: Estudio Nacional de Vigilancia de Infección Nosocomial en Servicios de Medicina Intensiva. https://hws.vhebron.net/envin-helics/.

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR, Trucchi C, Ansaldi F, Antonelli M, Adamkova V, Alicino C, Almyroudi MP, Atchade E, Azzini AM, Brugnaro P, Carannante N, Peghin M, Berruti M, Carnelutti A, Castaldo N, Corcione S, Cortegiani A, Dimopoulos G, Dubler S, García-Garmendia JL, Girardis M, Cornely OA, Ianniruberto S, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Lebihan C, Luzzati R, Malbrain M, Merelli M, Marques AJ, Martin-Loeches I, Mesini A, Paiva JA, Raineri SM, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Schouten J, Spapen H, Tasioudis P, Timsit JF, Tisa V, Tumbarello M, Van den Berg CHSB, Veber B, Venditti M, Voiriot G, Wauters J, Zappella N, Montravers P; from the Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients (ESGCIP) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID). Risk Factors for Intra-Abdominal Candidiasis in Intensive Care Units: Results from EUCANDICU Study. Infect Dis Ther. 2022 Apr;11(2):827-840. Epub 2022 Feb 19. PMID: 35182353; PMCID: PMC8960530. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti M, Vena A, Bouza E, Peghin M, Muñoz P, Righi E, Pea F, Lackner M, Lass-Flörl C. Antifungal susceptibility testing in Candida, Aspergillus and Cryptococcus infections: are the MICs useful for clinicians? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Aug;26(8):1024-1033. Epub 2020 Feb 29. PMID: 32120042. [CrossRef]

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011 Apr;24(2):247-80. PMID: 21482725; PMCID: PMC3122495. [CrossRef]

- Rawson TM, Antcliffe DB, Wilson RC, Abdolrasouli A, Moore LSP. Management of Bacterial and Fungal Infections in the ICU: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention Recommendations. Infect Drug Resist. 2023 May 4;16:2709-2726. PMID: 37168515; PMCID: PMC10166098. [CrossRef]

- Barantsevich N, Barantsevich E. Diagnosis and Treatment of Invasive Candidiasis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 May 26;11(6):718. PMID: 35740125; PMCID: PMC9219674. [CrossRef]

- Soriano A, Honore PM, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Vidal C, Pagotto A, Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Verweij PE. Invasive candidiasis: current clinical challenges and unmet needs in adult populations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023 Jul 5;78(7):1569-1585. PMID: 37220664; PMCID: PMC10320127. [CrossRef]

- León C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Castro C, Loza A, Zakariya I, Úbeda A, Parra M, Macías D, Tomás JI, Rezusta A, Rodríguez A, Gómez F, Martín-Mazuelos E; Cava Trem Study Group. Contribution of Candida biomarkers and DNA detection for the diagnosis of invasive candidiasis in ICU patients with severe abdominal conditions. Crit Care. 2016 May 16;20(1):149. Erratum in: Crit Care. 2017 May 15;21(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1686-1. PMID: 27181045; PMCID: PMC4867537. [CrossRef]

- Pittet D, Monod M, Suter PM, Frenk E, Auckenthaler R. Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg. 1994 Dec;220(6):751-8. PMID: 7986142; PMCID: PMC1234477. [CrossRef]

- León C, Ruiz-Santana S, Saavedra P, Almirante B, Nolla-Salas J, Alvarez-Lerma F, Garnacho-Montero J, León MA; EPCAN Study Group. A bedside scoring system ("Candida score") for early antifungal treatment in nonneutropenic critically ill patients with Candida colonization. Crit Care Med. 2006 Mar;34(3):730-7. PMID: 16505659. [CrossRef]

- Leroy G, Lambiotte F, Thévenin D, Lemaire C, Parmentier E, Devos P, Leroy O. Evaluation of "Candida score" in critically ill patients: a prospective, multicenter, observational, cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2011 Nov 30;1(1):50. PMID: 22128895; PMCID: PMC3247094. [CrossRef]

- Salmanton-García J, Cornely OA, Stemler J, Barać A, Steinmann J, Siváková A, Akalin EH, Arikan-Akdagli S, Loughlin L, Toscano C, Narayanan M, Rogers B, Willinger B, Akyol D, Roilides E, Lagrou K, Mikulska M, Denis B, Ponscarme D, Scharmann U, Azap A, Lockhart D, Bicanic T, Kron F, Erben N, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Goodman AL, Garcia-Vidal C, Lass-Flörl C, Gangneux JP, Taramasso L, Ruiz M, Schick Y, Van Wijngaerden E, Milacek C, Giacobbe DR, Logan C, Rooney E, Gori A, Akova M, Bassetti M, Hoenigl M, Koehler P. Attributable mortality of candidemia - Results from the ECMM Candida III multinational European Observational Cohort Study. J Infect. 2024 Sep;89(3):106229. Epub 2024 Jul 16. PMID: 39025408. [CrossRef]

- Nolla-Salas J, Sitges-Serra A, León-Gil C, Martínez-González J, León-Regidor MA, Ibáñez-Lucía P, Torres-Rodríguez JM. Candidemia in non-neutropenic critically ill patients: analysis of prognostic factors and assessment of systemic antifungal therapy. Study Group of Fungal Infection in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 1997 Jan;23(1):23-30. PMID: 9037636. [CrossRef]

- Morrell M, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Delaying the empiric treatment of candida bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are obtained: a potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Sep;49(9):3640-5. PMID: 16127033; PMCID: PMC1195428. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti M, Merelli M, Ansaldi F, de Florentiis D, Sartor A, Scarparo C, Callegari A, Righi E. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of candidemia: a five year single centre study. PLoS One. 2015 May 26;10(5):e0127534. PMID: 26010361; PMCID: PMC4444310. [CrossRef]

- Garey KW, Rege M, Pai MP, Mingo DE, Suda KJ, Turpin RS, Bearden DT. Time to initiation of fluconazole therapy impacts mortality in patients with candidemia: a multi-institutional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Jul 1;43(1):25-31. Epub 2006 May 16. PMID: 16758414. [CrossRef]

- Zilberberg MD, Kollef MH, Arnold H, Labelle A, Micek ST, Kothari S, Shorr AF. Inappropriate empiric antifungal therapy for candidemia in the ICU and hospital resource utilization: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010 Jun 3;10:150. PMID: 20525301; PMCID: PMC2890008. [CrossRef]

- Maseda E, Ramírez S, Picatto P, Peláez-Peláez E, García-Bernedo C, Ojeda-Betancur N, et al. Critically ill patients with community-onset intraabdominal infections: influence of healthcare exposure on resistance rates and mortality. PLoS One. 2019 Sep 26;14(9):e0223092.

- Shorr AF, Chung K, Jackson WL, Waterman PE, Kollef MH. Fluconazole prophylaxis in critically ill surgical patients: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2005 Sep;33(9):1928-35; quiz 1936. PMID: 16148461. [CrossRef]

- Vardakas KZ, Samonis G, Michalopoulos A, Soteriades ES, Falagas ME. Antifungal prophylaxis with azoles in high-risk, surgical intensive care unit patients: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2006 Apr;34(4):1216-24. PMID: 16484923. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Loeches I, Antonelli M, Cuenca-Estrella M, Dimopoulos G, Einav S, De Waele JJ, Garnacho-Montero J, Kanj SS, Machado FR, Montravers P, Sakr Y, Sanguinetti M, Timsit JF, Bassetti M. ESICM/ESCMID task force on practical management of invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2019 Jun;45(6):789-805. Epub 2019 Mar 25. PMID: 30911804. [CrossRef]

- Sartelli M, Catena F, Abu-Zidan FM, Ansaloni L, Biffl WL, Boermeester MA, Ceresoli M, Chiara O, Coccolini F, De Waele JJ, Di Saverio S, Eckmann C, Fraga GP, Giannella M, Girardis M, Griffiths EA, Kashuk J, Kirkpatrick AW, Khokha V, Kluger Y, Labricciosa FM, Leppaniemi A, Maier RV, May AK, Malangoni M, Martin-Loeches I, Mazuski J, Montravers P, Peitzman A, Pereira BM, Reis T, Sakakushev B, Sganga G, Soreide K, Sugrue M, Ulrych J, Vincent JL, Viale P, Moore EE. Management of intra-abdominal infections: recommendations by the WSES 2016 consensus conference. World J Emerg Surg. 2017 May 4;12:22. PMID: 28484510; PMCID: PMC5418731. [CrossRef]

- Roger C. Understanding antimicrobial pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients to optimize antimicrobial therapy: A narrative review. J Intensive Med. 2024 Feb 29;4(3):287-298. PMID: 39035618; PMCID: PMC11258509. [CrossRef]

- Theuretzbacher U. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of echinocandins. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004 Nov;23(11):805-12. Epub 2004 Oct 14. PMID: 15490294. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira JP, Neyra JA, Tolwani A. Continuous KRT: A Contemporary Review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023 Feb 1;18(2):256-269. Epub 2022 Aug 18. PMID: 35981873; PMCID: PMC10103212. [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999 Oct;12(4):501-17. PMID: 10515900; PMCID: PMC88922. [CrossRef]

- Grant SM, Clissold SP. Fluconazole. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs. 1990 Jun;39(6):877-916. Erratum in: Drugs 1990 Dec;40(6):862. PMID: 2196167. [CrossRef]

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez JA, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE, Sobel JD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 15;62(4):e1-50. Epub 2015 Dec 16. PMID: 26679628; PMCID: PMC4725385. [CrossRef]

- Greer ND. Voriconazole: the newest triazole antifungal agent. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003 Apr;16(2):241-8. PMID: 16278744; PMCID: PMC1201014. [CrossRef]

- Lewis JS 2nd, Wiederhold NP, Hakki M, Thompson GR 3rd. New Perspectives on Antimicrobial Agents: Isavuconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2022 Sep 20;66(9):e0017722. Epub 2022 Aug 15. PMID: 35969068; PMCID: PMC9487460. [CrossRef]

- Gioia F, Gomez-Lopez A, Alvarez ME, Gomez-García de la Pedrosa E, Martín-Davila P, Cuenca-Estrella M, Moreno S, Fortun J. Pharmacokinetics of echinocandins in suspected candida peritonitis: A potential risk for resistance. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Dec;101:24-28. Epub 2020 Sep 13. PMID: 32937195. [CrossRef]

- Hall RG 2nd, Liu S, Putnam WC, Kallem R, Gumbo T, Pai MP. Optimizing anidulafungin exposure across a wide adult body size range. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023 Nov 15;67(11):e0082023. Epub 2023 Oct 18. PMID: 37850741; PMCID: PMC10649049. [CrossRef]

- Sganga G, Wang M, Capparella MR, Tawadrous M, Yan JL, Aram JA, Montravers P. Evaluation of anidulafungin in the treatment of intra-abdominal candidiasis: a pooled analysis of patient-level data from 5 prospective studies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019 Oct;38(10):1849-1856. Epub 2019 Jul 6. PMID: 31280481; PMCID: PMC6778589. [CrossRef]

- Ham YY, Lewis JS 2nd, Thompson GR 3rd. Rezafungin: a novel antifungal for the treatment of invasive candidiasis. Future Microbiol. 2021 Jan;16(1):27-36. PMID: 33438477. [CrossRef]

- Bassetti M, Stewart A, Bartalucci C, Vena A, Giacobbe DR, Roberts J. Rezafungin acetate for the treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis: a pharmacokinetic evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2025 Jan-Feb;21(2):125-132. Epub 2024 Nov 18. PMID: 39552377. [CrossRef]

- Beredaki M-I, Arendrup MC, Pournaras S, Meletiadis J. Comparative pharmacodynamics and dose optimization of liposomal amphotericin B against Candida species in an in vitropharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2024 Aug 7;68(8):e0022524. Epub 2024 Jul 3. PMID: 38958455; PMCID: PMC11304708. [CrossRef]

- Azanza Perea JR. Anfotericina B liposomal: farmacología clínica, farmacocinética y farmacodinamia [Liposomal amphotericin B: Clinical pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2021 Apr-Jun;38(2):52-55. Spanish. Epub 2021 May 13. PMID: 33992527. [CrossRef]

- Maertens, J.; Marchetti, O.; Herbrecht, R.; Cornely,O.A.; Flückiger, U.; Frêre, P.; Gachot, B.; et al. European guidelines for antifungal management in leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: summary of the ECIL 3—2009 Update. Bone Marrow Transplant 46, 709–718 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2016; 62 (4): e1–e50. [CrossRef]

- A Cornely, O.A.; Bassetti, M.; Calandra, T.; Garbino, J.; Kullberg, B.J.; Lortholary, O.; Meersseman, W. et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect . 2012; 18( Suppl 7):19-37. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Loeches, I.; Antonelli, M.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Dimopoulos, G.; Einav, S.; Jan J De Waele, J.J. et al. ESICM/ESCMID task force on practical management of invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med 2019 ;45(6):789-805. Epub 2019 Mar 25. [CrossRef]

- Cornely, O.A.; Sprute, R.; Bassetti, M.; Chen, S.C-A.; Groll, A.H.; Kurzai, O. et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of candidiasis: an initiative of the ECMM in cooperation with ISHAM and ASM. Lancet Infect Dis 2025 Published Online February 13, 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).