Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

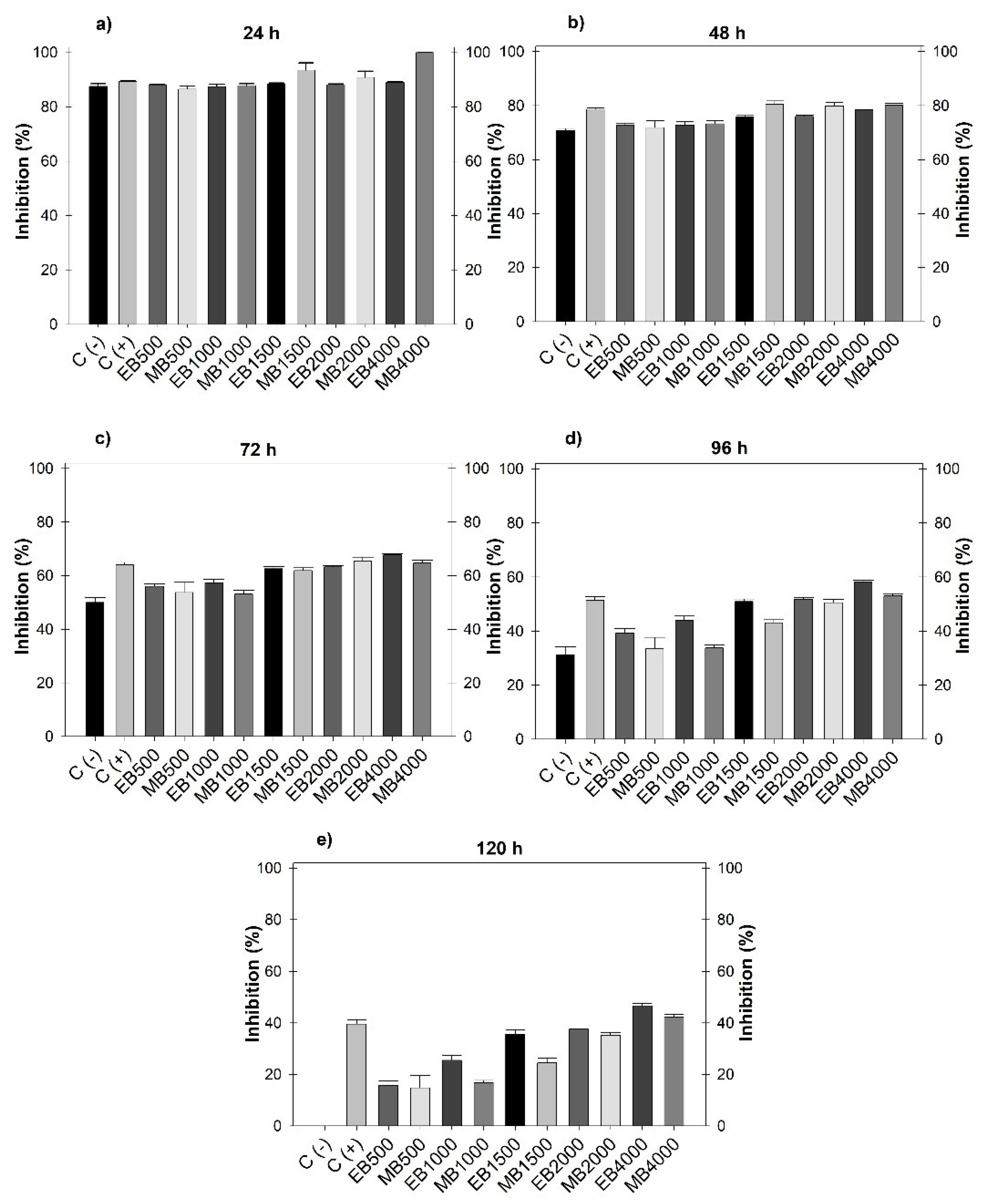

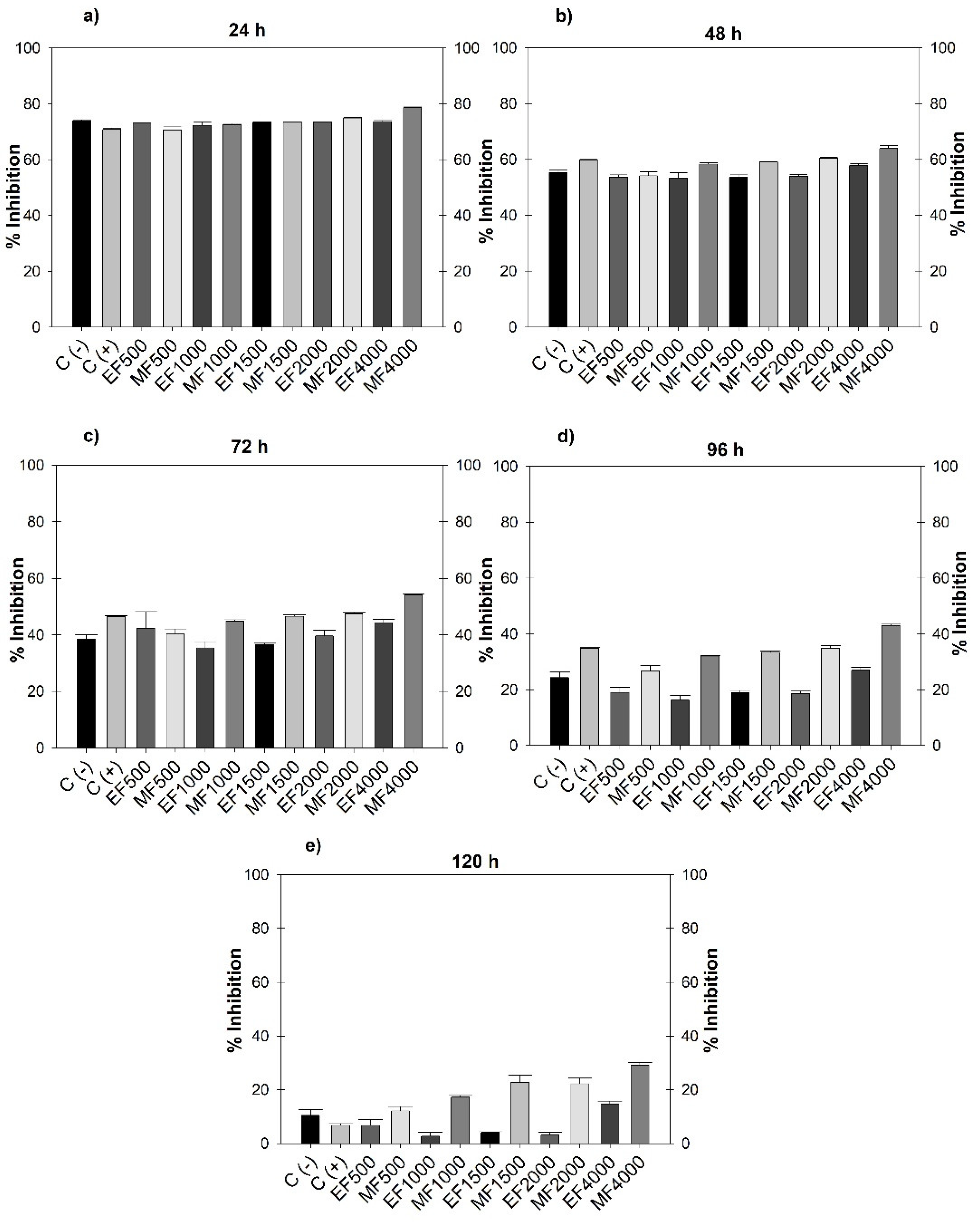

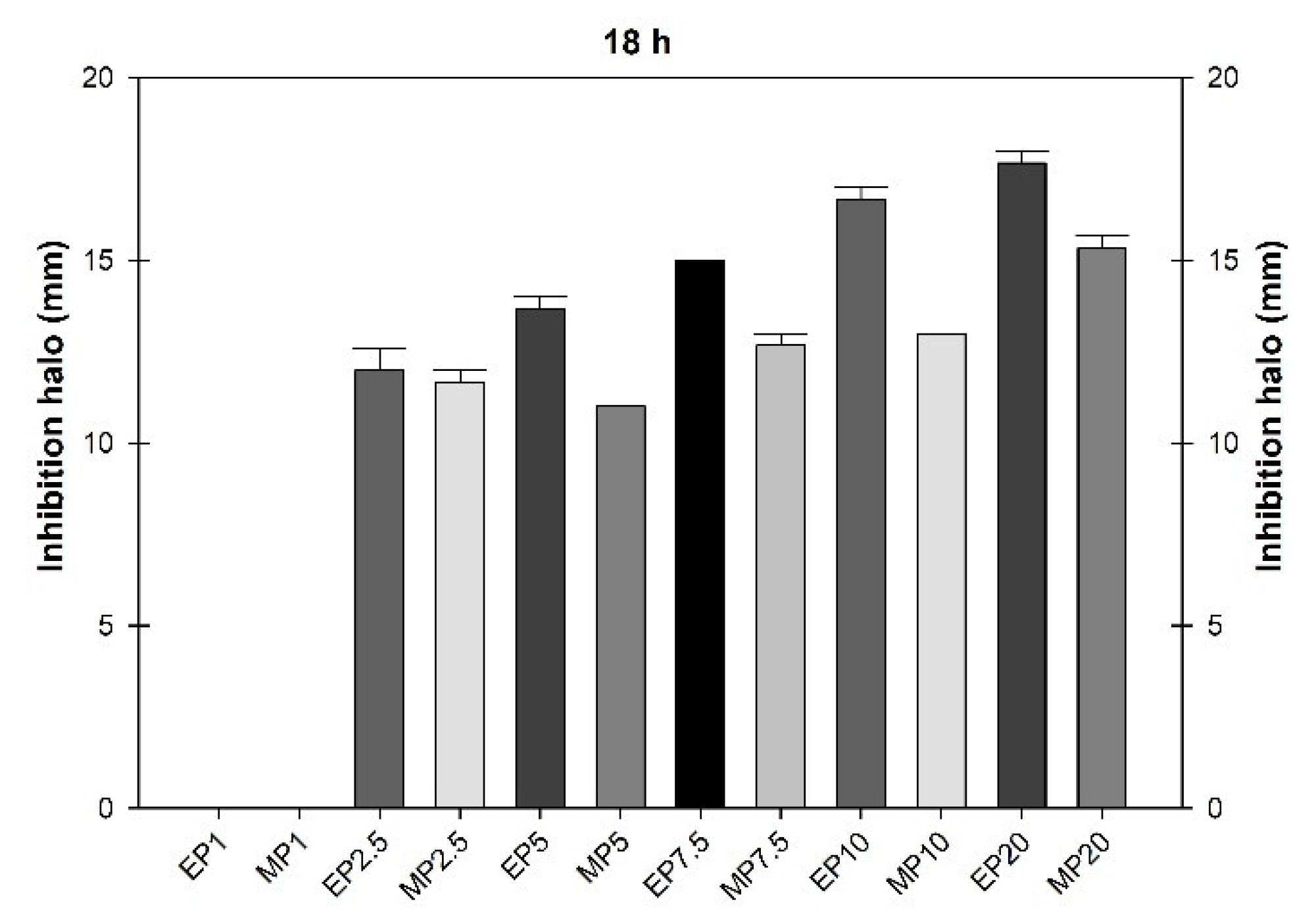

Jatropha dioica Sessé (JD) is a plant from arid and semiarid areas of Mexico, and has been linked to medicinal uses. Due to the current limitation of agrochemicals in agriculture and post-harvest due to environmental effects, health and resistance of phytopathogenic microorganisms, it is presumed that secondary metabolites of J. dioica can act as an alternative biological control. The bactericidal and fungistatic activity of hydroalcoholic extracts (ethanol and methanol) on Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium oxysporum and Pseudomonas syringae from J. dioica roots was evaluated in vitro, considering that the content of total phenols and flavonoids (Folin-Ciocalteu and aluminum chloride method) may have antimicrobial activity. The ethanolic and methanolic extracts have fungistatic biological activity on B. cinerea, with growth inhibition of 42.27 ±1.09 and 46.68 ±0.98% respectively and an IC50 of 5.04 mg mL-1 without significant differences in the use of solvents. In F. oxysporum, inhibition of 14.77 ±1.08 and 29.19 ±0.89% was obtained, where the methanolic extract was more efficient generating a stress response to the ethanolic extract. Regarding the bactericidal activity in P. syringae, the inhibition halo was 17.66 ±0.33 and 16.66 ±0.33 mm, showing slight difference when using ethanol. The phenolic content obtained was 8.92 ±0.25 and 12.10 ±0.34 mg EAG g-1 and flavonoids 20.49 ±0.33 and 28.21 ±0.73 mg QE g-1 of dry weight of the sample. The results highlight the importance of reorienting and revaluing J. dioica as an alternative source of metabolites for agricultural and post-harvest formulations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Plant Material and Preparation of the Extract

2.2. Inoculum Preparation

2.3. Preparation of Stock Solution and Fungistatic Activity

2.4. Bactericidal Activity

2.5. Total Phenol Analysis

2.6. Preparation of Gallic Acid Standard and Analysis of Flavonoids

3. Results

3.1. Fungistatic Activity

3.2. Bactericidal Activity

3.3. Total Phenol and Flavonoid Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Díaz Padilla, G.; Sánchez Cohen, I.; Guajardo Panes, R. A.; Ángel Pérez, A. L.; Ruíz Corral, A.; Medina García, G.; Ibarra Castillo, D. Mapeo del índice de aridez y su distribución poblacional en México. Revista Chapingo, Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente. 2011, 17, 267–275 . [Google Scholar]

- Guzzon, F.; Arandia Rios, L.W.; Caviedes Cepeda, G.M.; Céspedes Polo, M.; Chavez Cabrera, A.; Muriel Figueroa, J.; Medina Hoyos, A.E.; Jara Calvo, T.W.; Molnar, T.; Narro León, L.A.; Narro León, T.P.; Mejía Kerguelén, S.L.; Ospina Rojas, J.G.; Vázquez, G.; Preciado Ortiz, R.E.; Zambrano, J.L.; Palacios Rojas, N.; Pixley, K. Conservation and Use of Latin American Maize Diversity: Pillar of Nutrition Security and Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Agronomy. 2021, 11, 1, 172 . [Google Scholar]

- Villavicencio Gutiérrez, E. E.; Cano Pineda, A.; Castillo Quiroz, D.; Hernández Ramos, A.; Martínez Burciaga, O. U. Manejo forestal sustentable de los recursos no maderables en el semidesierto del norte de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales. 2021, 12, 31–63 [Google Scholar] [CroosRef]. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal. Catálogo de recursos forestales maderables y no maderables. Available online: https://www.conafor.gob.mx/biblioteca/Catalogo_de_recursos_forestales_M_y_N.pdf. (accessed on 3 march 2024).

- Dávila Rangel, I. E.; Charles Rodríguez, A. V.; López Romero, J. C.; Flores López, M. L. Plants from Arid and Semi-Arid Zones of Mexico Used to Treat Respiratory Diseases: A Review. Plants. 2024, 13, 6 . [Google Scholar]

- Llauradó Maury, G.; Méndez Rodríguez, D.; Hendrix, S.; Escalona Arranz, J. C.; Fung Boix, Y.; Ochoa Pacheco, A.; García Díaz, J.; Morris Quevedo, H. J.; Ferrer Dubois, A.; Isaac Aleman, I.; Beenaerts, N.; Méndez Santos, I. E.; Orberá Ratón, T.; Cos, P.; Cuypers, A. Antioxidants in Plants: A Valorization Potential Emphasizing the Need for the Conservation of Plant Biodiversity in Cuba. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 11,1048 [CrossRef] [PubMed]. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Calderas, J. M.; Palacio Núñez, J.; Sanchez Rojas, G.; Martinez Montoya, J.F.; Olmos Oropeza, G.; Clemente Sanchez, F. Distribución y abundancia de Jatropha dioica en el centro-norte de México. Agrociencia. 2019, 53, 3, 433–446 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Moreno, A.; García Garza, R.; Pedroza Escobar, D.; Soto Domínguez, A.; Flores Loyola, E.; Castillo Maldonado, I.; Keita, H.; Núñez, I.; Delgadillo Guzmán, D. Antioxidant Effect of Jatropha dioica Extract on Immunoreactivity of Claudin 2 in the Kidney of Rats with Induced Diabetes. Natural Product Communications. 2023, 18, 3 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Espino, D. I.; Zamora Perez, A. L.; Zúñiga González, G. M.; Gutiérrez Hernández, R.; Morales Velazquez, G.; Lazald Ramos, B. P. Genotoxic and cytotoxic evaluation of Jatropha dioica Sessé ex Cerv. by the micronucleus test in mouse peripheral blood. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2020, 86, 260–264 . [Google Scholar]

- Rani, L.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S.; Grewal, A. S.; Srivastav, A. L.; Kaushal, J. An extensive review on the consequences of chemical pesticides on human health and environment. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 283.

- Jabłońska Trypuć, A.; Wydro, U.; Wołejko, E.; Makuła, M.; Krętowski, R.; Naumowicz, M.; Sokołowska, G.; Serra Majem, L.; Cechowska Pasko, M.; Łozowicka, B.; Kaczyński, P.; Wiater, J. Selected Fungicides as Potential EDC Estrogenic Micropollutants in the Environment. Molecules. 2023, 28, 21, 7437 . [Google Scholar]

- Herrera González, J. A.; Bautista Baños, S.; Salazar García, S.; Gutiérrez Martínez, P. Manejo Postcosecha aguacate Situación actual del manejo poscosecha y de enfermedades fungosas del aguacate ‘Hass’ para exportación. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2020, 11, 7, 1647–1660 . [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Henríquez, L.; Alfaro Aguilar, K.; Ugalde Álvarez, J.; Vega Fernández, L.; Montes de Oca Vásquez, G.; Vega Baudrit, J. R. Green Synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles from plant extracts and their possible applications as antimicrobial agents in the Agricultural area. Nanomaterials. 2020, 10, 9, 1763 . [Google Scholar]

- López Sánchez, A.; Luque Badillo, A.C.; Orozco Nunnelly, D.; Alencastro Larios, N.S.; Ruiz Gómez, J.A.; García Cayuela, T.; Gradilla Hernández, M.S. Food loss in the agricultural sector of a developing country: Transitioning to a more sustainable approach. The case of Jalisco, Mexico. Environmental Challenges. 2021, 5, 100327 . [Google Scholar]

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura. Available online: https://www.fao.org/home/es (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Chandrasekaran, I.; Geetha, P. Postharvest technology and value addition of tomatoes. Food Science Research Journal. 2020, 11, 2, 217–229 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Savary, S.; Ficke, A.; Aubertot, J.N.; Hollier, C. Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security. Food Security. 2012, 4, 519–537 . [Google Scholar]

- Różewicz, M.; Wyzińska, M.; Grabiński, J. The most important fungal diseases of cereals, problems and possible solutions. Agronomy. 2021, 11, 4 . [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, T.; Brião Muniz, M. F.; Spolaor Fantinel, V.; Harakava, R.; Mengue Rolim, J. Characterization and pathogenicity of Fusarium oxysporum associated with Carya illinoinensis seedlings. Floresta e Ambiente. 2020, 27, 2 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Velarde Félix, S.; Garzón Tiznado, J. A.; Hernández Verdugo, S.; López Orona, C. A.; Retes Manjarrez, J. E. Occurrence of Fusarium oxysporum causing wilt on pepper in Mexico. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology. 2018, 40, 2, 238–247 . [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, P. E.; Toussoun, T. A.; Marasas, W. F. O. Fusarium Species: An Illustrated Manual for Identification, 1rd edition; Pennsylvania State University Press. 1983.

- Ahmed, F.; Sipes, B.; Alvarez, A. Postharvest diseases of tomato and natural products for disease management. African Journal of Agricultural. 2017, 12, 9, 684–691 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Romanazzi, G.; Feliziani, E. Botrytis cinerea (Gray Mold). In Postharvest Decay; Bautista Baños, S. Elsevier: Yautepec Morelos, México, 2014; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, L.; Yong, C.; Zhanquan, Z.; Boqiang, L.; Guozheng, Q.; Shiping, T. Pathogenic mechanisms and control strategies of Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest decay in fruits and vegetables. Food Quality and Safety. 2018, 2, 3, 111–119 . [Google Scholar]

- Preston, G. M. Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato: The right pathogen, of the right plant, at the right time. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2001, 1, 5, 263–275 . [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J. R.; Messéan, A.; Morris, C. E. Insights into epidemiology and control of diseases of annual plants caused by the Pseudomonas syringae species complex. Journal of General Plant Pathology. 2015, 81, 5, 331–350 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B.; Tudzynski, B.; Tudzynski, P.; Van Kan, J. Botrytis cinerea: The cause of grey mould disease. Molecular Plant Pathology. 2007, 8, 5, 561–580 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, A.; Manoharachary, C. Future challenges in crop protection against fungal pathogens; Springer: New York, NY, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jasso, D.; Salas Méndez, E.; Rodríguez García, R.; Hernández Castillo, F. D.; Díaz Jiménez, M. L. V.; Sáenz Galindo, A., González Morales, S.; Flores López, M. L.; Villarreal Quintanilla, J. A.; Peña Ramos, F. M.; Carrillo Lomelí, D. A. Antifungal activity in vitro of ethanol and aqueous extracts of leaves and branches of Flourensia spp. Against postharvest fungi. Industrial Crops and Products. 2017, 107, 499-508.

- Villa, P.; Alfonso, I.; Rivero, M.J.; González, G. Evaluación de cepas de Bacillus subtilis bioantagonistas de hongos fitopatógenos del género Fusarium. ICIDCA, sobre los derivados de la caña de azúcar. 2007, XLI, 1, 52-56.

- Comisión Nacional del Agua. Precipitación y temperatura actual diaria. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conagua (accessed on 24 march 2023).

- Al Sa’ady, A.T. Antibacterial screening for five local medicinal plants against nosocomial pathogens: Klebsiella pneumoniae and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur Asian Journal of BioScienses. 2020, 14, 553–559 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Belmares, Y.; Rivas Morales, C.; Viveros Valdez, E.; De la Cruz Galicia, M.; Carranza Rosales, P. Antimicrobial and citotoxic activities from Jatropha dioica roots. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020, 17, 5, 748–750 . [Google Scholar]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S. K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2016, 6, 2, 71–79 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuyal, N.; Kumar, P.; Raturi, P. P.; Rajbhandary, S. Total Phenolic, Flavonoid Contents, and Antioxidant Activities of Fruit, Seed, and Bark Extracts of Zanthoxylum armatum DC. The Scientific World Journal. 2020, 1.

- Ramírez Moreno, E.; Morales, P.; Cortes Sanchez, M.; Carvalho, A. M.; Ferreira, I. Nutritional and antioxidant properties of pulp and seeds of two xoconostle cultivars (Opuntia joconostle F. A.C. Weber ex Diguet and Opuntia matudae Scheinvar) of high consumption in Mexico. Food research International, 2012, 46, 1, 279–285 . [Google Scholar]

- Siti Fairuz, Y.; Farah Farhanah, H.; Mahmud Tengku, M.; Norhayu, A.; Siti Zaharah, S.; Faizab Abu, K.; Siti Izera, I. Antifungal Activity and phytochemical screening of Vernonia amygdalina extract against Botrytis cinerea causing gray mold disease on tomato fruits. Biology. 2020, 9, 286 . [Google Scholar]

- Nechita, A.; Filimon, R.; Filimon, R.; Colibaba, L.; Gherghel, D.; Damian, D.; Pașa, R.; Cotea, V. In vitro Antifungal Activity of a new bioproduct obtained from grape seed proanthocyanidins on Botrytis cinerea mycelium and spores. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2019, 47, 2, 418–425 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dėnė, L.; Valiuškaitė, A. Sensitivity of Botrytis cinerea isolates complex to plant extracts. Molecules. 2021, 26, 15, 4595 . [Google Scholar]

- Dellavalle, P. D.; Cabrera, A.; Alem, D.; Larrañaga, P.; Ferreira, F.; Dalla Riza, M. Antifungal activity of medicinal plant extracts against phytopathogenic fungus Alternaria spp. Chilean Journal of Agricultural research. 2011, 71, 231–239 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Moreno, A.; Serrano Gallardo, L. B.; Barragán Ledezma, L. E.; Quintanar Escorza, M. A.; Arellano Pérez, D.; Delgadillo Guzmán, D. Determinación de los compuestos polifenólicos en extractos de Jatropha dioica y su capacidad antioxidante. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Farmacéuticas. 2016, 47, 4, 42–48 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Topolovec Pintaric, S. Plant Diseases: Current Threats and Management Trends; Intech Open: Zagreb, Croacia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tarun Kumar, P.; Kamlesh, S.; Ramsingh, K.; Seema,U.; Rajendra, J.; Ravishankar, C. Phytochemical screening and determination of phenolics and flavonoids in Dillenia pentagyna using UV–vis and FTIR spectroscopy. Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy.2020, 242, 10.

- Rongai, D.; Pulcini, P.; Pesce, B.; Milano, F. Antifungal activity of some botanical extracts on Fusarium oxysporum. Open Life Sciences. 2015, 10, 409–416 . [Google Scholar]

- Frérot, B.; Leppik, E.; Groot, A. T.; Unbehend, M.; Holopainen, J. K. Chemical signatures in plant insect interactions. In Advances in Botanical Research; Sauvion, N.; Thiéry, D. Calatayud. Academic Press; Italia, Francia, 2017; 81, pp. 139-177.

- Cotoras, M.; Mendoza, L.; Muñoz, A.; Yáñez, K.; Castro, P.; Aguirre, M. Fungitoxicity against Botrytis cinerea of a flavonoid isolated from Pseudognaphalium robustum. Molecules. 2011, 16, 5 . [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo Salinas, L. S. Actividad antifúngica de Sechium compositum contra Botrytis cinerea y Colletotrichum gloeosporioides en condiciones in vitro. 2019.

- Gutiérrez Tlahque, J.; Aguirre Mancilla, C. L.; López Palestina, C.; Sánchez Fernández, R. E.; Hernández Fuentes, A. D.; Torres Valencia, J.M. Constituents, antioxidant and antifungal properties of Jatropha dioica var. dioica. Natural product communications. 2019, 14, 5 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar, N.; Perveen, A. Solvent polarity effects on extraction yield, phenolic content, and antioxidant properties of Malvaceae family seeds: A comparative study. New Zealand Journal of Botany. 2024, 1-11.

- Tucuch Pérez, M. A.; Arredondo Valdés, R.; Hernández Castillo, F. D. Antifungal activity of phytochemical compounds of extracts from Mexican semi desert plants against Fusarium oxysporum from tomato by microdilution in plate method. Nova Scientia. 2020, 12, 25 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Jae Ki, Y., Kap Hee, R.; Jeong Hyun, K.; Sung Sunk, L.; Young Joon, A. Fungicidal activity of oriental medicinal plant extracts against plant pathogenic fungi. Applied Biological Chemistry. 1998, 41, 8, 600-604.

- Al Rahmah, A. N.; Mostafa, A. A.; Abdel Megeed, A.; Yakout, S. M.; Husssein, S. A. Fungicidal activities of certain methanolic plant extracts against tomato phytopathogenic fungi. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2013, 7, 6, 517–524 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Arcusa, R.; Villaño, D.; Marhuenda, J.; Cano, M.; Cerdà, B.; Zafrilla, P. Potential role of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) in the prevention of neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2022, 9.

- Saleem, A.; Afzal, M.; Naveed, M.; Makhdoom, S. I.; Mazhar, M.; Aziz, T.; Khan, A. A.; Kamal, Z.; Shahzad, M.; Alharbi, M.; Alshammari, A. HPLC, FTIR and GC-MS analyses of Thymus vulgaris phytochemicals executing in vitro and in vivo biological activities and effects on COX-1, COX-2 and gastric cancer genes computationally. Molecules. 2022, 27, 23 . [Google Scholar]

- Sanches Silva, A.; Tewari, D.; Sureda, A.; Suntar, I.; Belwal, T.; Battino, M.; Nabavi, S. M.; Nabavi, S. F. The evidence of health benefits and food applications of Thymus vulgaris L. Trends In Food Science & Technology. 2021, 117, 218–227 . [Google Scholar]

- Villota Burbano, J. E.; Vazquez Ochoa, O. Y. Evaluación in vitro del extracto etanólico de hojas de borraja (Borago officinalis) contra la actividad fungistática. Agronomía Costarricense. 2021, 45, 2, 9–27 . [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, N.; Almaguer, G.; Vázquez Alvarado, P.; Figueroa, A.; Zúñiga, C.; Hernández Ceruelos, A. Análisis fitoquímico de Jatropha dioica y determinación de su efecto antioxidante y quimioprotector sobre el potencial genotóxico de ciclofosfamida, daunorrubicina y metilmetanosulfonato evaluado mediante el ensayo cometa. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas. 2014, 13, 5, 437–457 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas Hernández, J. A. Efecto de la esterilización sobre compuestos bioactivos de los extractos del fruto xoconostle ulapa (opuntia oligacantha) y de la planta sangre de drago (jatropha dioica sessé ex cerv.) con posible aplicación antimicrobiana en productos bucales. Doctoral thesis, Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, Pachuca, Hidalgo, 2019.

- Pérez Pérez, J. U.; Guerra Ramírez, D.; Reyes Trejo, B.; Cuevas Sánchez, J. A.; Guerra Ramírez, P. ; Actividad antimicrobiana in vitro de extractos de Jatropha dioica Seseé contra bacterias fitopatógenas de tomate. Polibotánica. 2020, 49, 125–133 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizi, H.; Tahan, V.; Kariman, K. In vitro antibacterial activity of essential oils from Carum copticum and Ziziphora clinopodioides plants against the phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. Syringae. Plant Biosystems - An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology. 2022, 157, 2, 487–492 . [Google Scholar]

- Mougou, I.; Boughalleb, N. Biocontrol of Pseudomonas syringae pv. Syringae affecting citrus orchards in Tunisia by using indigenous Bacillus spp. And garlic extract. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control. 2018, 28, 60.

- Lidiková, J.; Čeryová, N.; Tomáš, T.; Musilová, J.; Vollmannová, A.; Kushvara, M. Garlic (Allium sativum L.): Characterization of bioactive compounds and related health benefits. On herbs and spices; Ivanišová, E.; Slovaquia, Europa, 2023, pp. 280.

- Lu, M.; Pan, J.; Hu, Y.; Ding, L.; Li, Y.; Cui, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C. Advances in the study of vascular related protective effect of garlic (Allium sativum) extract and compounds. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2024, 124, 109531 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez Martínez, F. J.; Barrajón Catalán, E.; Herranz López, M.; Micol, V. Antibacterial plant compounds, extracts and essential oils: An updated review on their effects and putative mechanisms of action. Phytomedicine: International Journal of Phytotherapy and Phytopharmacology. 2021, 90, 153626 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotulong, V.; Wonggo, D.; Montolalau, L. Phytochemical content, total phenols, and antioxidant activity of mangrove sonneratia albaYoung leaf through different extraction methods and solvents. International Journal of ChemTech Research. 2018, 11, 11 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, L.; Hesham, S.; Khalifa, S. A. M.; Mohammadhosseini, M.; Sarker, S. D. Ruta essential oils: Composition and bioactivities. Molecules. 2021, 26, 16 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Najiyah, H. W.N.; Narul Najiha, A.I.; Woon Kuo, H.; Azliana Abu, B. S.; Noor Soffalina, S. S.; Wan Aida, W. M.; Hafeedza Abdul, R. Effects of different drying methods and solvents on biological activities of Curcuma aeruginosa leaves extract. Sains Malaysiana. 2021, 50, 8, 2207–2218 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Las Heras, R.; Heredia, A.; Castelló, M. L.; Andrés, A. Influence of drying method and extraction variables on the antioxidant properties of persimmon leaves. Food Bioscience. 2014, 6, 1–8 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Machado, A. C.; Torres León, C.; Castillo Maldonado, I.; Delgadillo Guzmán, D.; Hernández Morales, C.; Flores Loyola, E.; Marszalek, J. E.; Balagurusamy, N.; Vega Menchaca, M.; Ascacio Valdés, J. A.; Pedroza Escobar, D.; Ramírez Moreno, A. Content of polyphenolic compounds, flavonoids, antioxidant activity and antibacterial activity of Jatropha dioica hydroalcoholic extracts against Streptococcus mutans. International Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2023, 58, 12 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda Ledesma, N. E.; Aguilar Zárate, P.; Bautista Hernández, I.; Rojas, R.; Robledo Jiménez, C. L.; Martínez Ávila, G. C. G. The optimization of ultrasound assisted extraction for bioactive compounds from Flourensia cernua and Jatropha dioica and the evaluation of their functional properties. Horticulturae. 2024, 10, 7 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibuye, B.; Singh, S. I.; Chimuka, L.; Maseka, K. K. A review of modern and conventional extraction techniques and their applications for extracting phytochemicals from plants. Scientific African. 2023, 19.

- Osorio Tobón, J. F. Recent advances and comparisons of conventional and alternative extraction techniques of phenolic compounds. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2020, 57, 12 . [Google Scholar]

- Chetoui, I.; Messaoud, C.; Boussaid, M.; Zaouali, Y. Antioxidant activity, total phenolic and flavonoid content variation among Tunisian natural populations of Rhus tripartita (Ucria) Grande and Rhus pentaphylla Desf. Industrial Crops and Products. 2013, 51.

- Pandey, G.; Khatoon, S.; Pandey, M. M.; Rawat, A. K. S. Altitudinal variation of berberine, total phenolics and flavonoid content in Thalictrum foliolosum and their correlation with antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine. 2018, 9, 3 . [Google Scholar]

- Rieger, G.; Müller, M.; Guttenberger, H.; Bucar, F. Influence of altitudinal variation on the content of phenolic compounds in wild populations of Calluna vulgaris, Sambucus nigra, and Vaccinium myrtillus. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2008, 56, 19 . [Google Scholar]

- Papoti, V. T.; Xystouris, S.; Papagianni, G.; Tsimidou, M. Z. Total flavonoid content assesment via aluminum complexation reactions. What we really measure?. Italian Journal of Food Science. 2011, 23, 252–258 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, L.; Timalsena, S.; Duwadi, P.; Thapa, R.; Paudel, A.; Parajuli, K. Antioxidant activity and phenol and flavonoid contents of eight medicinal plants from Western Nepal. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2014, 34, 584–590 . [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar Patle, T.; Shrivas, K.; Kurrey, R.; Upadhyay, S.; Jangde, R.; Chauhan, R. Phytochemical screening and determination of phenolics and flavonoids in Dillenia pentagyna using UV–vis and FTIR spectroscopy. Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2020, 242, 10 . [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N. Q.; Nguyen, M. T.; Nguyen, V. T.; Le, V. M.; Trieu, L. H.; Le, X. T.; Khang, T. V.; Giang, N. T. L.; Thach, N. Q.; Hung, T. T. The effects of different extraction conditions on the polyphenol, flavonoids components and antioxidant activity of Polyscias fruticosa roots. Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020, 736, 022067 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Amjad, M. S.; Talaat, A.A; Mizanur, R.; Yousef, H. Determination of total flavonoid content by aluminum chloride assay: A critical evaluation. Food Science and Technology. 2021, 150, 11 . [Google Scholar]

- Raposo, F.; Borja, R.; Gutiérrez González, J. A. A comprehensive and critical review of the unstandardized Folin-Ciocalteu assay to determine the total content of polyphenols: The conundrum of the experimental factors and method validation. Talanta. 2024, 272, 125771 . [Google Scholar]

- Anokwuru, C.P.; Anyasor, G.N.; Ajibaye, O.; Fakoya, O.; Okebugwu, P. Effect of extraction solvents on phenolic, flavonoid and antioxidant activities of three Nigerian medicinal plants. Nature and Science. 2011, 9, 7, 53–61 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R. N.; Wallsgrove, R. M. Secondary metabolites in plant defence mechanisms. New Phytologist. 1994, 127, 4, 617–633 . [Google Scholar]

- Guerra Ramírez, P.; Guerra Ramírez, D.; Zavaleta Mejía, E.; Aranda Ocampo, S.; Nava Díaz, C.; Rojas Martínez, R. I. Extracts of Stevia rebaudiana against Fusarium oxysporum associated with tomato cultivation. Scientia Horticulturae. 2020, 259.

- Kahkashan, A.; Samir, K. B.; Mohd, R. Biochemical evidences of defence response in tomato against Fusarium wilt induced by plant extracts. Plant Pathology Journal. 2012, 11, 2 . [Google Scholar]

- Mani López, E.; Cortés Zavaleta, O.; López-Malo, A. A review of the methods used to determine the target site or the mechanism of action of essential oils and their components against fungi. SN Applied Sciences, 3, 44.

- Hafiz Abdul, R.; Abdur, R.; Aiman, K.; Fahad, A.; Haiying, C.; Lin, L. A comprehensive insight into plant-derived extracts/bioactives: Exploring their antimicrobial mechanisms and potential for high-performance food applications. Food Bioscience. 2024, 59.

- Bajpai, V. K.; Rahman, A.; Dung, N. T.; Huh, M. K.; Kang, S. C. In vitro inhibition of food spoilage and foodborne pathogenic bacteria by essential oil and leaf extracts of Magnolia liliflora Desr. Journal of Food Science. 2008, 73, 6 . [Google Scholar]

- Tereschuk, M.L.; Quarenghi, M.; González, M.; Baigorí, M.D. Antimicrobial activity of isolated flavonoids from argentine Tagetes. Boletín Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas. 2007, 6, 6 [Google Scholar]. [Google Scholar]

- Dahua Gualinga, R. D.; Rivera Barreto, J. L.; Rodríguez Almeida, N. N.; Sancho Aguilera, D. Actividad antimicrobiana, antifúngica y tamizaje fitoquímico de Simira cordifolia. Código Científico Revista De Investigación. 2024, 5, 1 . [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Ortega, L.A.; Valdez Baro, O.; Heredia Bátiz, J.M.; García Estrada, R.S.; Basilio, H.J. ; Control de fitopatógenos con extractos de biomasa de chile y de maíz. TIP Revista Especializada en Ciencias Químico Biológicas. 2023. 26, 1.

- Domínguez Ruvalcaba, J. E.; Calderón Santoyo, M.; González Gutiérrez, K. N.; Ragazzo Sanchez, J. A. Extracto polifenólico de hojas de mango (Mangifera indica L.): Microencapsulación, caracterización fisicoquímica y actividad antifúngica in vivo. Biotecnia. 2024, 26.

| Concentration (µg mL-1) | Extract (mL) | H2O distilled (mL) |

| 500 | 5.8 | 44.2 |

| 1000 | 11.5 | 38.5 |

| 1500 | 17.3 | 32.7 |

| 2000 | 23.1 | 26.9 |

| 4000 | 46.2 | 3.8 |

| Concentration (µg mL-1) | Extracts (µL) | H2O distilled (µL) |

| 1000 | 20 | 980 |

| 2500 | 50 | 950 |

| 5000 | 100 | 900 |

| 7500 | 150 | 850 |

| 10000 | 200 | 800 |

| 20000 | 400 | 600 |

| Solvent | Total phenol content (TPC) mg EAG/g |

Flavonoid content (TFC) mg QE/g |

| Ethanol | 8.92 ±0.25 | 20.49 ±0.33 |

| Methanol | 12.10 ±0.34 | 28.21 ±0.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).