Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Methanolic Extract

2.3. Chitosan Solution

2.4. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity

2.4.1. Radial Growth Kinetics

2.4.2. Cell Viability Test

2.4.3. Cell Integrity Damage Analysis

2.5. Phytotoxicity Bioassay

2.6. Acute Toxicity Test in Artemia salina

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity

3.1.1. Radial Growth Kinetics

3.1.2. Cell Viability Test

3.1.3. Cell Integrity Damage Analysis

3.2. Phytotoxicity Bioassay

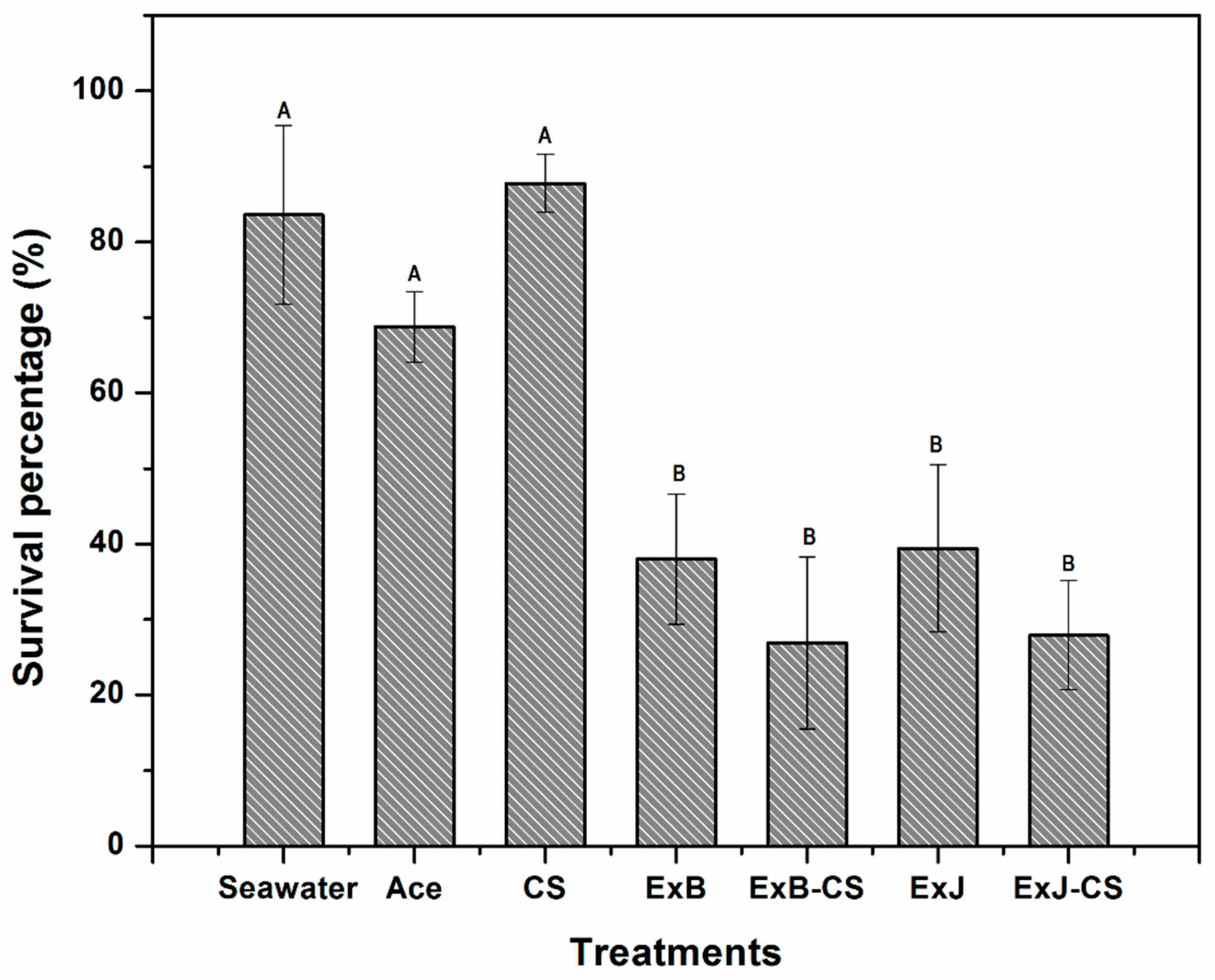

3.3. Acute Toxicity Test in Artemia salina

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, R.A.; Najeeb, S.; Hussain, S.; Li, Y. Bioactive secondary metabolites from Trichoderma spp. against phytopathogenic fungi. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahadevakumar, S.; Sridhar, K.R. Diversity of Pathogenic Fungi in Agricultural Crops. In Plant, Soil and Microbes in Tropical Ecosystems, 1st ed.; Dubey, S.K., Verma, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 101–149. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo-Báez, I.; Álvarez, B.; García, R.S.; León, J.; Sañudo, A.; Allende, R. Situación actual de Colletotrichums spp. en México: Taxonomía, caracterización, patogénesis y control. Rev Mex Fitopatol 2017, 35, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Aragón, D.; Silva-Rojas, H.V.; Guarnaccia, V.; Mora-Aguilera, J.A.; Aranda-Ocampo, S.; Bautista-Martínez, N.; Téliz-Ortíz, D. Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose on avocado fruit in Mexico: Current status. Plant Pathol 2020, 69, 1513–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Estrada, R.S.; Cruz-Lachica, I.; Osuna-García, L.A.; Márquez-Zequera, I. First Report of Papaya (Carica papaya) anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum plurivorum in Mexico. Plant Dis 2020, 104, 589–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinidad-Ángel, E.; Ascencio, F.; Ulloa, J.A.; Ramírez, J.C.; Ragazzo, J.A.; Calderón, M.; Bautista, P.U. Identificación y caracterización de Colletotrichum spp. causante de antracnosis en aguacate de Nayarit, México. Rev Mex Cienc Agric 2017, 8, 3953–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofini, A.; Negrini, F.; Baroncelli, R.; Baraldi, E. Management of post-harvest anthracnose: current approaches and future perspectives. Plants 2022, 11, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, S.; Agha, S.; Jamil, N.; Tabassum, B.; Ahmed, S.; Raheem, A.; Khan, A. Characterization and survival of broad-spectrum biocontrol agents against phytopathogenic fungi. Rev Argent Microbiol 2022, 54, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khetabi, A.; Lahlali, R.; Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Lyousfi, N.; Banani, H.; Askarne, L.; Tahiri, A.; El Ghadraoui, L.; Belmalha, S.; Ait Barka, E. Role of plant extracts and essential oils in fighting against postharvest fruit pathogens and extending fruit shelf life: A review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 120, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznanski, P.; Hameed, A.; Orczyk, W. Chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles: Parameters enhancing antifungal activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras-Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An overview of its properties and applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellis, A.; Guebitz, G.M.; Nyanhongo, G.S. Chitosan: Sources, processing and modification techniques. Gels 2022, 8, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Bi, X.; Dai, Y.; Ren, R. Enhancing mango anthracnose control and quality maintenance through chitosan and iturin A coating. LWT 2024, 198, 115955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.I.G.; Stamford, T.C.M.; Melo, N.F.C.B.; Nunes, I.D.S.; Lima, M.A.B.; Pintado, M.M.E.; Stamford-Arnaud, T.M.; Stamford, N.P.; Stamford, T.L.M. Chitosan–citric acid edible coating to control Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and maintain quality parameters of fresh-cut guava. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 163, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Burgos, E.C.; Cortez-Rocha, M.O.; Cinco-Moroyoqui, F.J.; Robles-Zepeda, R.E.; López-Cervantes, J.; Sánchez-Machado, D.I.; Lares-Villa, F. Antifungal activity in vitro of Baccharis glutinosa and Ambrosia confertiflora extracts on Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus parasiticus and Fusarium verticillioides. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2009, 25, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitimea-Cantúa, G.V.; Rosas-Burgos, E.C.; Cinco-Moroyoqui, F.J.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M.; Cortez-Rocha, M.O.; Gálvez-Ruiz, J.C. In vitro effect of antifungal fractions from the plants Baccharis glutinosa and Jacquinia macrocarpa on chitin and β-1,3-glucan hydrolysis of maize phytopathogenic fungi and on the fungal β-1,3-glucanase and chitinase activities. J Food Saf 2013, 33, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Magdaleno, M.E., Luque-Alcaraz, A.G., Gutiérrez-Martínez, P., Cortez-Rocha, M.O., Burgos-Hernández, A., Lizardi-Mendoza, J., Plascencia-Jatomea, M. Effect of chitosan-pepper tree (Schinus molle) essential oil biocomposites on the growth kinetics, viability and membrane integrity of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Rev Mex Ing Quim 2018, 17, 29–45. [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Espinosa, R.; Delgado, L.; Casals, E.; González, E.; Puntes, V.; Barata, C.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. Acute toxicity of cerium oxide, titanium oxide and iron oxide nanoparticles using standardized tests. Desalination 2011, 269, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Marroquín, L.A.; Martínez-Bolaños, M.; Cruz-Chávez, M.A.; Ariza-Flores, R.; Cruz-López, J.A.; Magaña-Lira, N.; Cruz-de-la-Cruz, L.L.; Ariza-Hernández, F.J. Inhibition of mycelial growth and conidium germination of Colletotrichum sp. for organic and inorganic products. Agro Prod 2022, 15, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghaouth, A.; Arul, J.; Grenier, J.; Asselin, A. Antifungal activity of chitosan on two postharvest pathogens of strawberry fruits. Phytopathology 1992, 82, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sosa, K.; Sánchez-Medina, A.; Álvarez, S.L.; Zacchino, S.; Veitch, N.C.; Simá-Polanco, P.; Peña-Rodríguez, L.M. Antifungal activity of sakurasosaponin from the root extract of Jacquinia flammea. Nat Prod Res 2011, 25, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel-Pérez, J.; Fukusaki, A.; Enciso, N.; Altamirano, C.; Mayanga-Herrera, A.; Marcelo, Á.; Marin-Sánchez, O. Interferencia de pigmentos vegetales al aplicar la técnica XTT a extractos de Buddleja globosa, Senecio tephrosiodes Turcz y Equisetum giganteum. Científica 2016, 13, 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, M.P.; Nozari, R.M.; Santarém, E.R. Herbicidal activity of natural compounds from Baccharis spp. on the germination and seedlings growth of Lactuca sativa and Bidens pilosa. Allelopathy J 2017, 42, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurliana, S.; Fachriza, S.; Hemelda, N.M. Chitosan application for maintaining the growth of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) under drought condition. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Food and Agriculture (ICOFA), Jember, Indonesia, 6–7 November 2021; IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 980, 012013. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Téllez, C.N.; Luque-Alcaraz, A.G.; Núñez-Mexía, S.A.; Cortez-Rocha, M.O.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Rosas-Burgos, E.C.; Rosas-Durazo, A.; Parra-Vergara, N.V.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M. Relationship between the antifungal activity of chitosan–capsaicin nanoparticles and the oxidative stress response on Aspergillus parasiticus. Polymers 2022, 14, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Cortés, A.; Almendariz-Tapia, F.; Gómez-Álvarez, A.; Burgos-Hernández, A.; Luque-Alcaraz, A.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M. Toxicological assessment of cross-linked beads of chitosan-alginate and Aspergillus australensis biomass, with efficiency as biosorbent for copper removal. Polymers 2019, 11, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoopathy, S.; Inbakandan, D.; Thirugnanasambandam, R.; Kumar, C.; Sampath, P.; Bethunaickan, R.; Raguraman, V.; Vijayakumar, G.K. A comparative study on chitosan nanoparticle synthesis methodologies for application in aquaculture through toxicity studies. IET Nanobiotechnol 2021, 15, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Time (h) |

Chitosan (CS) | B. glutinosa (ExB) | J. macrocarpa (ExJ) | |||

| 2 mg/mL | 4 mg/mL | 2 mg/mL | 4 mg/mL | 2 mg/mL | 4 mg/mL | |

| 24 | 100 ± 0.0a | 100 ± 0.0a | 100 ± 0.0a | 100 ± 0.0a | 100 ± 0.0a | 100 ± 0.0a |

| 48 | 60.9 ± 2.7b | 62.4 ± 2.3b | 100 ± 0.0a | 100 ± 0.0a | 43.7 ± 2.3c | 42.1 ± 2.7c |

| 72 | 29.5 ± 0.8d | 47.0 ± 3.7b | 79.6 ± 2.5a | 81.1 ± 1.5a | 45.1 ± 5.9bc | 38.3 ± 1.7c |

| 96 | 26.6 ± 1.4d | 46.3 ± 1.8b | 71.8 ± 0.7a | 72.6 ± 1.8a | 42.3 ± 6.0bc | 33.8 ± 5.6cd |

| 120 | 22.4 ± 1.5d | 42.5 ± 2.6Cb | 63.3 ± 1.5a | 67.2 ± 2.3a | 41.8 ± 3.9b | 33.7 ± 2.6c |

| 144 | 25.7 ± 1.0d | 39.8 ± 11.2c | 62.5 ± 0.8a | 66.8 ± 2.5a | 45.4 ± 1.2b | 38.2 ± 2.3c |

| 168 | 27.6 ± 0.0f | 38.6 ± 0.9e | 63.5 ± 0.6b | 67.6 ± 0.4a | 47.4 ± 0.6c | 43.3 ± 0.4d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).