Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of the BH Patients and Control Subjects

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Thoracis Aorta Homogenization

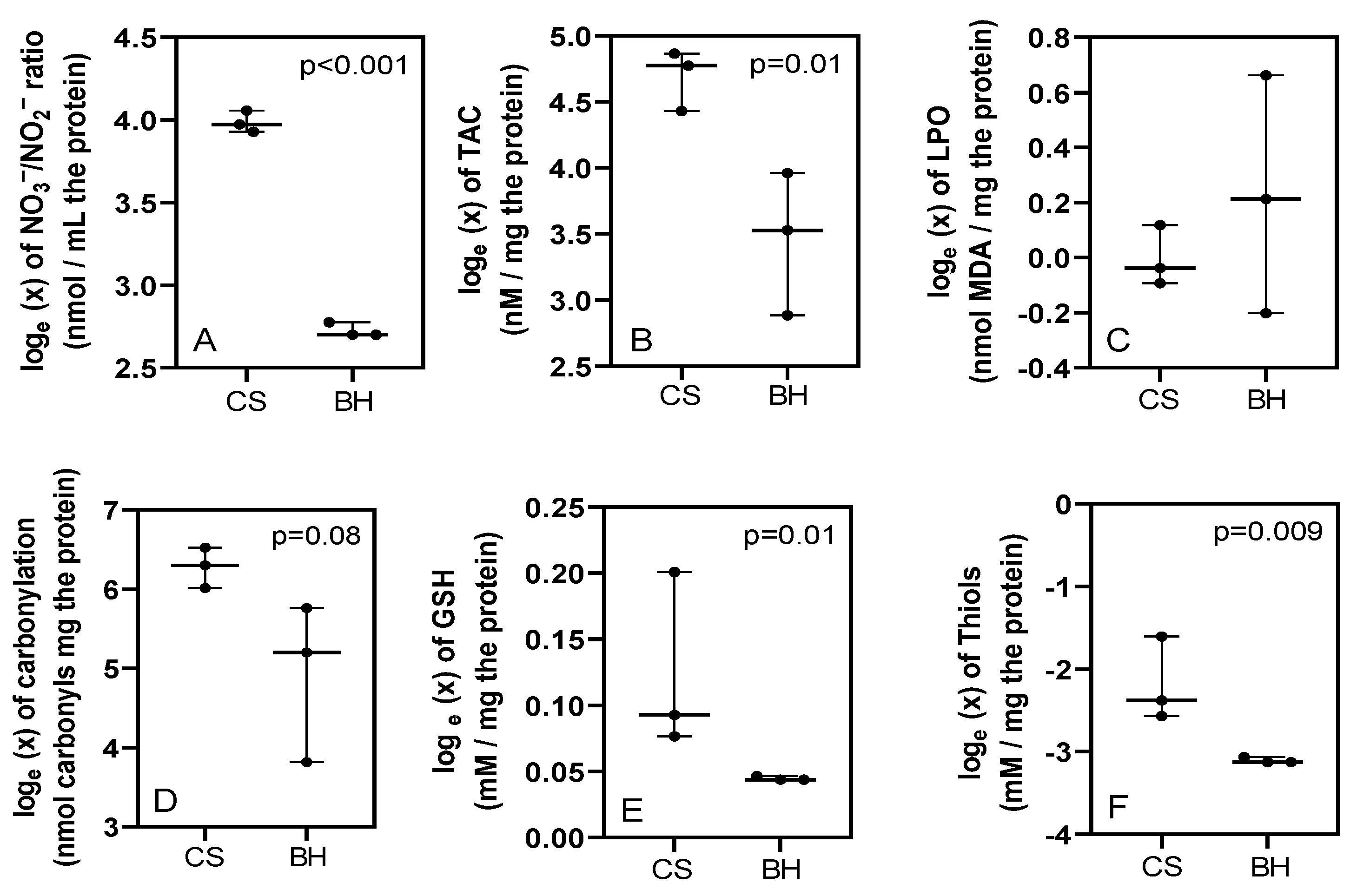

2.3.1. Oxidative Stress Markers

2.3.2. Determination of Malondialdehyde

2.3.3. Evaluation of the Total Antioxidant Capacity

2.3.4. Carbonylation

2.3.5. GSH and Thiols

2.3.6. NO3−/NO2− Ratio Determination

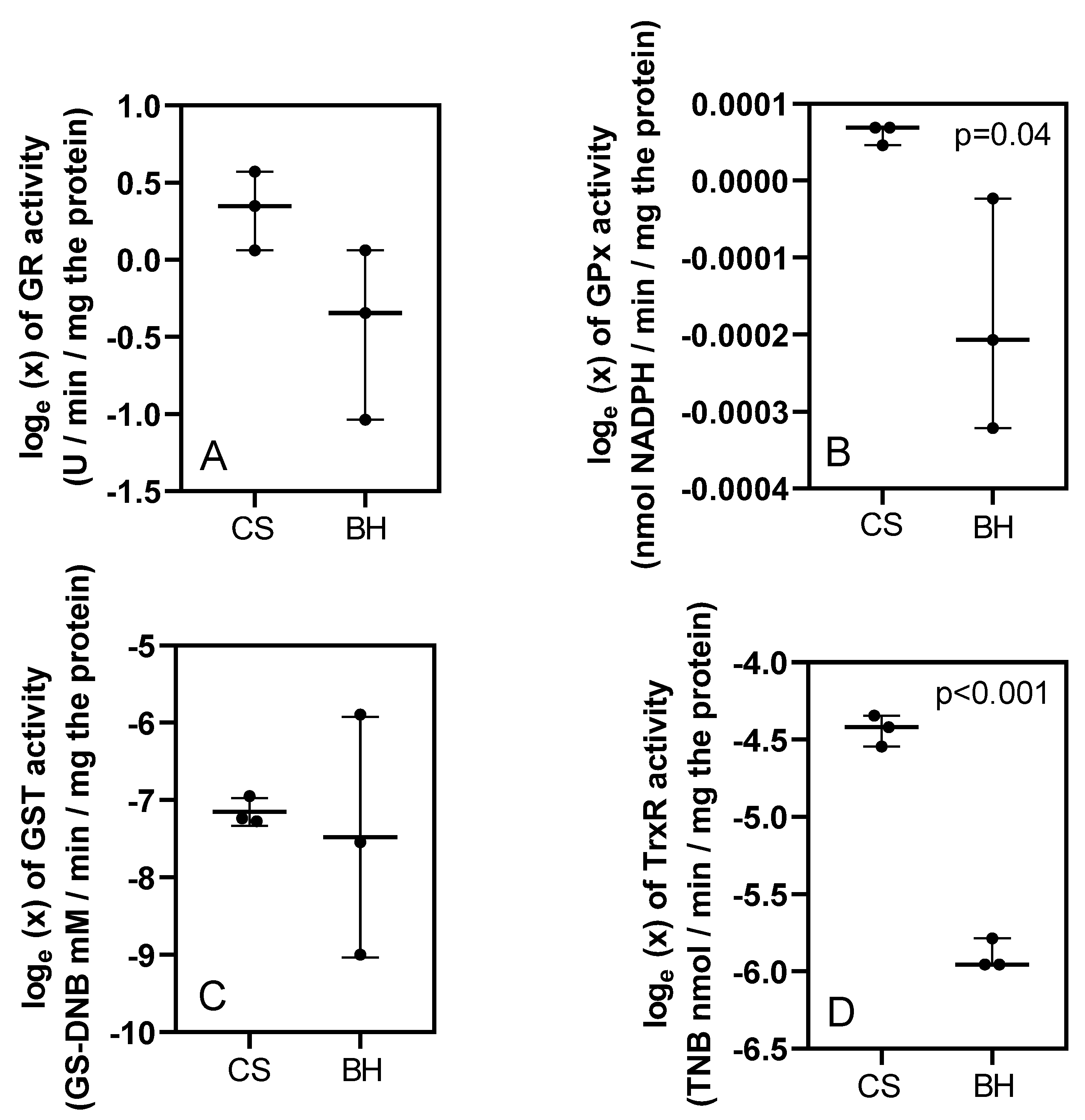

2.3.7. Determinations of Antioxidant Enzymes That Employ GSH as a Substrate

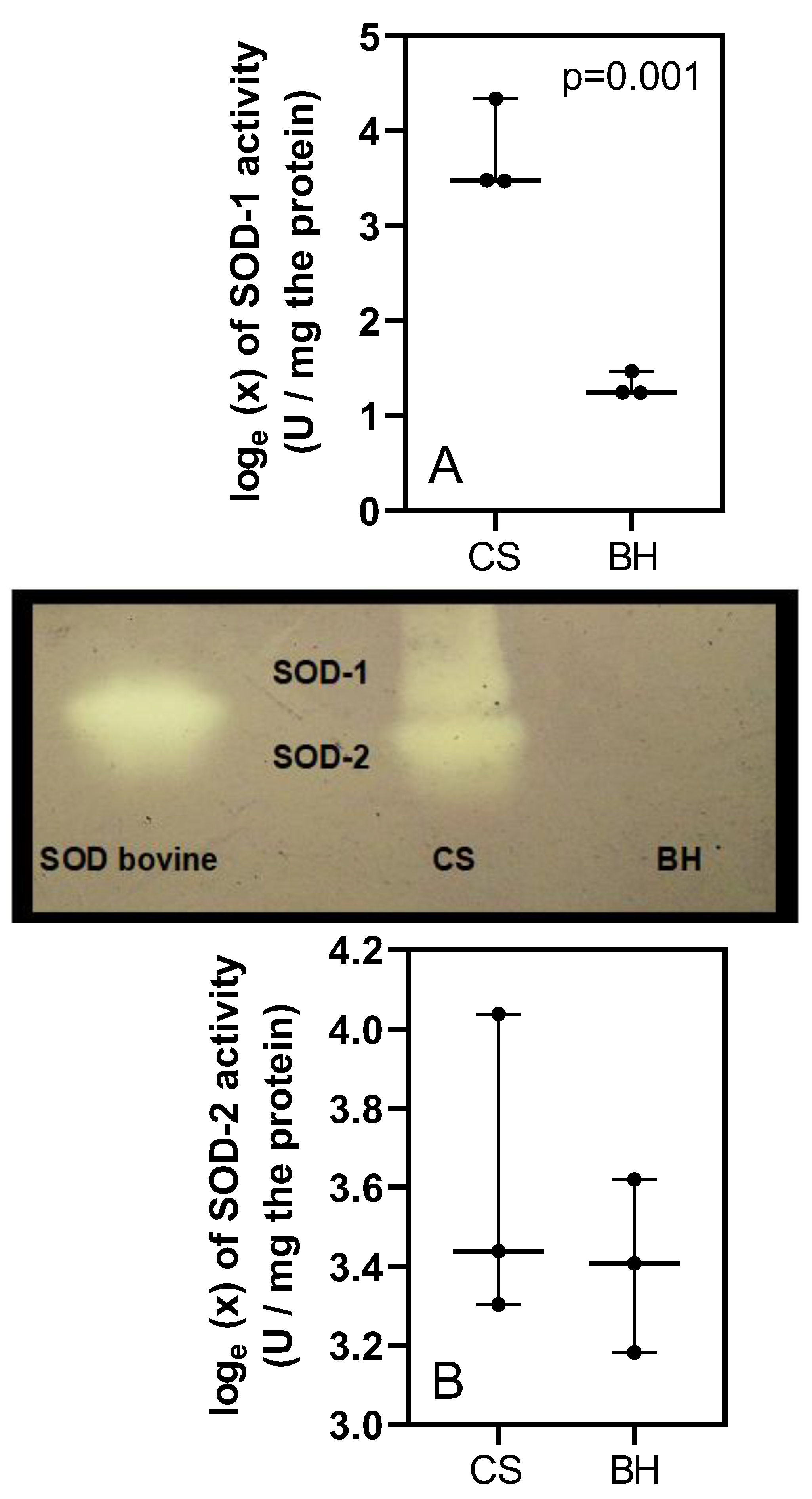

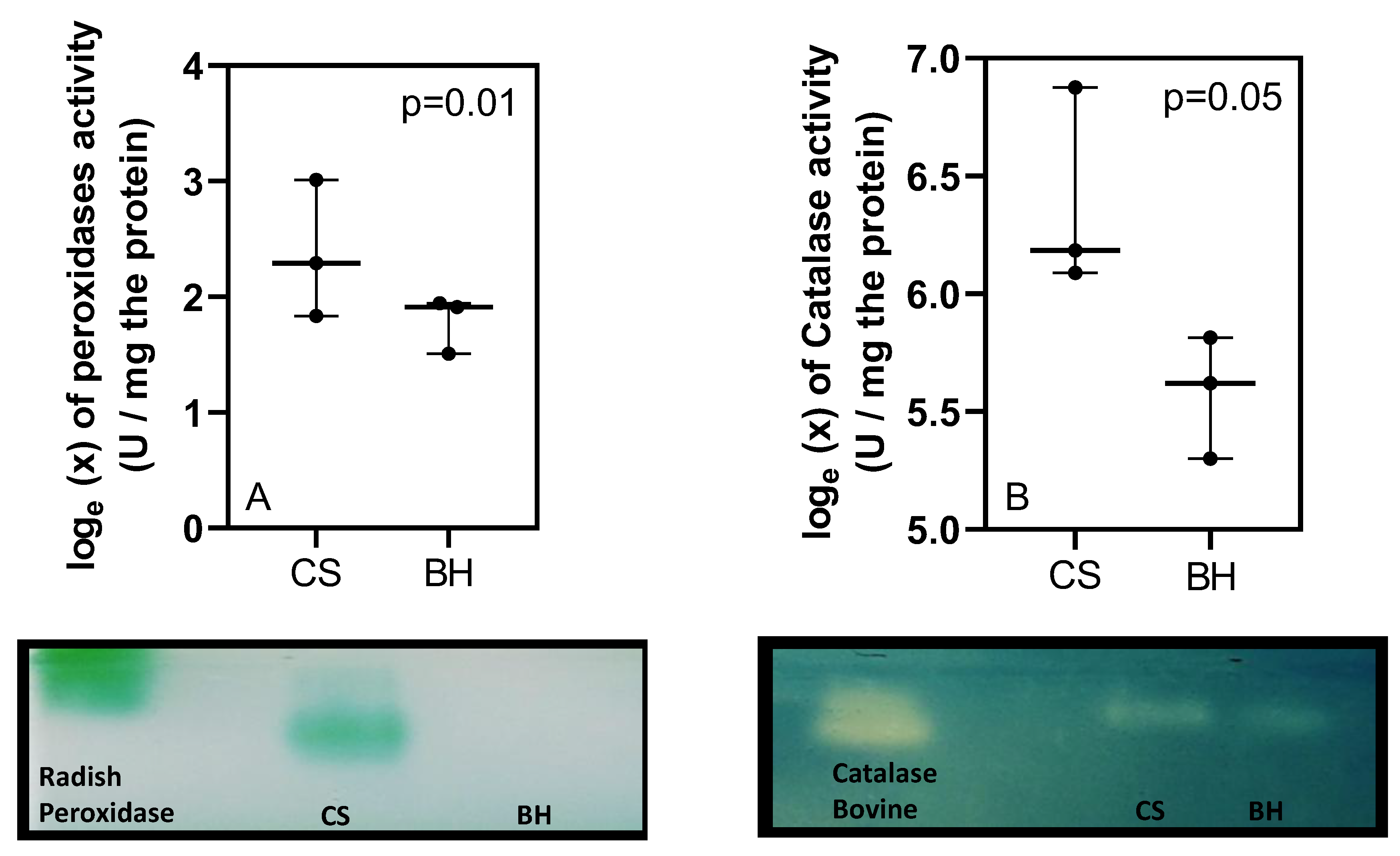

2.3.8. Determinations of Super Oxide Dismutase Isoforms, Catalase and Peroxidases Activities

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Study Limitations

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, A.L.; He, J.Q.; Zeng, L.; Hu, Y.Q.; Wang, M.; Long, J.Y.; Chang, S.H.; Jin, J.Y.; Xiang, R. Case report: Identification of novel <i>fibrillin-2</i> variants impacting disulfide bond and causing congenital contractural arachnodactyly. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1035887. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Qiao, F.; Cheng, Q.; Luo, C.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, P.; Xu, Z. A Novel splice site mutation in the FBN2 Gene in a Chinese family with congenital contractural arachnodactyly. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 2495–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaldone, S.; Ramirez, F. Fibrillin microfibrils in bone physiology. Matrix. Biol. 2016, 52-54, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zodanu, G.K.E.; Hwang, J.H.; Mehta, Z.; Sisniega, C.; Barsegian, A.; Kang, X.; Biniwale, R.; Si, M.S.; Satou, G.M.; Halnon, N.; Grody, W.W.; Van Arsdell, G.S.; Nelson, S.F.; Touma, M. High-throughput genomics identify novel FBN1/2 variants in severe neonatal Marfan syndrome and congenital heart defects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, Z. FBN2 pathogenic variants in congenital contractural arachnodactyly with severe cardiovascular manifestations. Connect. Tissue. Res. 2024, 65, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zúñiga-Muñoz, A.M.; Pérez-Torres, I.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Núñez-Garrido, E.; Velázquez Espejel, R.; Huesca-Gómez, C.; Gamboa-Ávila, R; Soto, M. E. Glutathione system participation in thoracic aneurysms from patients with Marfan syndrome. Vasa. 2017, 46, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Soto, M.E.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Díaz-Diaz, E.; Soria-Castro, E.; Rubio-Ruíz, M.E.; Guarner-Lans, V. Oxidative stress in plasma from patients with Marfan syndrome is modulated by deodorized garlic preliminary findings. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5492127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.E.; Pérez-Torres, I.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Soria-Castro, E.; Morales-Marín, A.; E. S.; Martínez-Hernández, H.; Herrera-Alarcón, V.; Guarner-Lans, V. Reduced levels of selenium and thioredoxin reductase in the thoracic aorta could contribute to aneurysm formation in patients with Marfan syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndebele, P. The declaration of Helsinki, 50 years later. JAMA. 2013, 310, 2145–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentall, H.; De Bono, A. A technique for complete replacement of the ascending aorta. Thorax. 1968, 23, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, M.E.; Soria-Castro, E.; Lans, V.G.; Ontiveros, E.M.; Mejía, B.I.; Hernandez, H.J.; García, R.B.; Herrera, V.; Pérez-Torres, I. Analysis of oxidative stress enzymes and structural and functional proteins on human aortic tissue from different aortopathies. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 760694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, M.E.; Manzano-Pech, L.G.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Díaz-Galindo, J.A.; Vásquez, X.; Castrejón-Tellez, V.; Gamboa, R.; Huesca, C.; Fuentevilla-Alvárez, G.; Pérez-Torres, I. ; Oxidant/antioxidant profile in the thoracic aneurysm of patients with the Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5392454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Roque, P.; El-Hafidi, M.; Diaz-Diaz, E.; Baños, G. Association of renal damage and oxidative stress in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Influence of gender. Free. Rad. Res. 2009, 43, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerschaut, I.; De Coninck, S.; Steyaert, W.; Barnicoat, A.; Bayat, A.; Benedicenti, F.; Berland, S.; Blair, E.M.; Breckpot, J.; de Burca, A.; Destrée, A.; García-Miñaúr, S.; Green, A.J.; Hanna, B.C.; Keymolen, K.; Koopmans, M.; Lederer, D.; Lees, M.; Longman, C.; Lynch, S.A.; Male, A.M.; McKenzie, F.; Migeotte, I.; Mihci, E.; Nur, B.; Petit, F.; Piard, J.; Plasschaert, F.S.; Rauch, A.; Ribaï, P.; Pacheco, I.S.; Stanzial, F.; Stolte-Dijkstra, I.; Valenzuela, I.; Varghese, V.; Vasudevan, P.C.; Wakeling, E.; Wallgren-Pettersson, C.; Coucke, P.; De Paepe, A.; De Wolf, D.; Symoens, S.; Callewaert, B. A clinical scoring system for congenital contractural arachnodactyly. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.A.; Putnam, E.A.; Carmical, S.G.; Kaitila, I.; Steinmann, B.; Child, A.; Danesino, C.; Metcalfe, K.; Berry, S.A.; Chen, E.; Delorme, C.V.; Thong, M.K.; Ades. L.C.; Milewicz, D.M. Ten novel FBN2 mutations in congenital contractural arachnodactyly: delineation of the molecular pathogenesis and clinical phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 2002, 19, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phokaew, C.; Sittiwangkul, R.; Suphapeetiporn, K.; Shotelersuk, V. Double heterozygous variants in FBN1 and FBN2 in a Thai woman with Marfan and Beals syndromes. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 63, 103982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Martínez, C.; Lamas, O.; Mataró, M.J.; Robledo-Carmona, J.; Sánchez-Espín, G.; Moreno-Santos, I.; Carrasco-Chinchilla, F.; Gallego, P.; Such-Martínez, M.; de Teresa, E.; Jiménez-Navarro, M.; Fernández, B. Fibrillin 2 is upregulated in the ascending aorta of patients with bicuspid aortic valve. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 51, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.E.; Wheller, J.J. Cardiac defects in a patient with congenital contractural arachnodactyly. South. Med. J. 1985, 78, 742–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, N, Morita H, Fujita D, Inuzuka R, Taniguchi Y, Imai Y, Hirata Y, Komuro I. Congenital contractural arachnodactyly complicated with aortic dilatation and dissection: Case report and review of literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2015, 167A, 2382–2387. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Li, R.; Huang, S.; Sun, M.; Liu, J.; Niu, Y.; Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, M.; Li, X.; Xuan, Gao. ; Yuan, Gao. A novel splicing mutation in the FBN2 gene in a family with congenital contractural arachnodactyly. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Deslee, G. Woods, J.C. Moore, C.M. Liu, L. Conradi, S.H. Milne, M. Gierada, D.S. Pierce, J. Patterson, A.; Lewit, R.A.; Battaile, J.T.; Holtzman, M.J.; Hogg, J.C.; Pierce, R.A. Elastin expression in very severe human COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

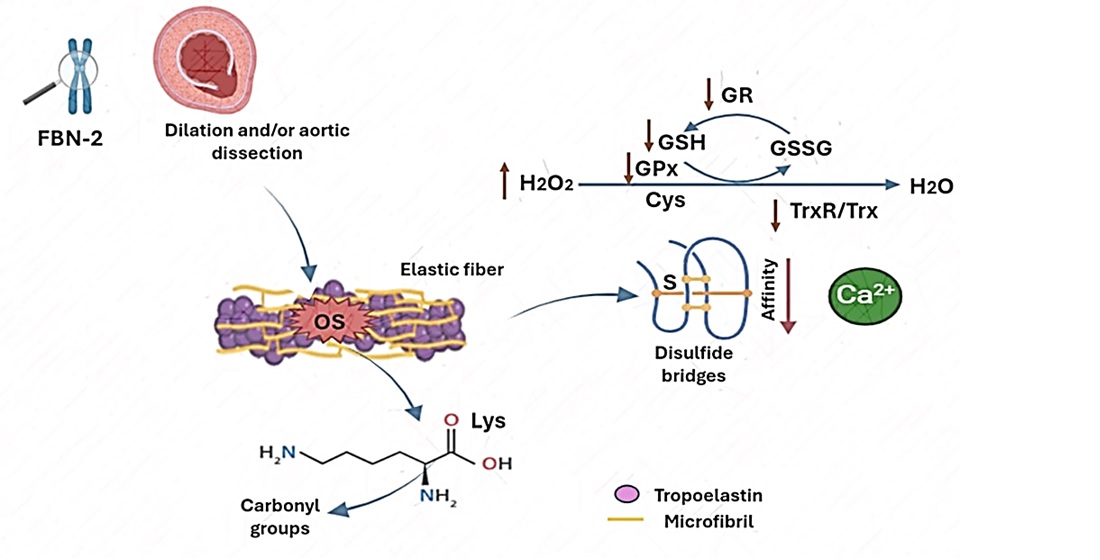

- Ramirez, F.; Sakai, L.Y. Biogenesis and function of fibrillin assemblies. Cell. Tissue. Res. 2010, 339, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, D.P.; Gambee, J.E.; Ono, R.N.; Bachinger, H.P.; Sakai, L.Y. Initial steps in assembly of microfibrils. Formation of disulfide-cross-linked multimers containing fibrillin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, A.K.; Knott, V.; Werner, J.M.; Cardy, C.M.; Campbell, I.D.; Handford, P.A. Solution structure of a pair of calcium-binding epidermal growth factor-like domains: implications for the Marfan syndrome and other genetic disorders. Cell. 1996, 85, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupakhin, E.; Krasavin, M. Thioredoxin reductase inhibitors: Updated patent review (2017–present). Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 31, 745–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Holmgren, A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 66, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, J.; Schneider, H.; Pagel, J.I.; Rehberg, M.; Singer, M.; Hellfritsch, J.; Chillo, O.; Schubert, K.M.; Qiu, J.; Pogoda, k. , Kameritsch, P.; Uhl, B.; Pircher, J.; Deindl, E.; Müller, S.; Kirchner, T.; Pohl, U.; Conrad, M.; Beck. H.; Endothelial dysfunction, and a prothrombotic, proinflammatory phenotype is caused by loss of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase in endothelium. Arterioscler. Throm. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, L.Y.; Keene, D.R.; Engvall, E. Fibrillin, a new 350-kD glycoprotein, is a component of extracellular microfibrils. J. Cell. Biol. 1986, 103, 2499–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talot, T.; Conconi, M. T.; Di Liddo, R. Structural and functional failure of fibrillin-1 in human diseases (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 41, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Lubos, E.; Loscalzo, J.; Handy, D.E. Glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Ant. Red. Sig. 2011, 15, 1957–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.E.; Iturriaga-Hernández, A.V.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Zuñiga-Muñoz, A.; Aranda-Fraustro, A.; Velázquez-Espejel, R.; Pérez-Torres, I. Participation of oleic acid in the formation of the aortic aneurysm in Marfan syndrome patients. Prost. Other. Lipid. Mediat. 2016, 123, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, F.P.; Raman, A.V.; Reeves, M.A.; Berry, M.J. Regulation and function of selenoproteins in human disease. Biochem. J. 2009, 422, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degendorfer, G.; Chuang, C.Y.; Mariotti, M.; Hammer, A.; Hoefler, G.; Hägglund, P.; Malle, E.; Wise, S.G.; Davies, M.J. Exposure of tropoelastin to peroxynitrous acid gives high yields of nitrated tyrosine residues, di-tyrosine cross-links and altered protein structure and function. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 15, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, K.; Broekelmann, T.J.; Miao, M.; Keeley, F.W.; Starcher, B.C.; Pierce, R.A.; Mecham, R.P.; Adair-Kirk, T.L. Oxidative and nitrosative modifications of tropoelastin prevent elastic fiber assembly in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37396–37404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.C. Regulation of glutathione synthesis. Mol. Aspects. Med. 2009, 30, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deponte, M. Glutathione catalysis and the reaction mechanisms of glutathione-dependent enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1830, 3217–3266. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, A. Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 17205–17208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, GM, Moore T, Le A, et al. Degree of glutathione deficiency and redox imbalance depend on subtype of mitochondrial disease and clinical status. PLoS. One. 2014, 9, e100001. [Google Scholar]

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

| Age at the time of diagnosis | 29 | 53 | 25 |

| Age (current post surgery and intervention) | 30 | 66 | 36 |

| Gender | Man | Man | Man |

| Ghent criteria > 2 is required for classification | |||

|

No | No | No |

| Aortic root dilation (mm) | 41 | 31 | 19 |

| Sinus of Valsalva dilation (mm) | 91 | 52 | 27 |

| Sino tubular junction dilation (mm) | 90 | 38 | 24.7 |

| Ascending aorta dilation (mm) | 46 | 37 | 28 |

| Abdominal Aorta | Without dilation | 33 | 36 |

|

yes | yes | yes |

|

No | No | No |

| Systemic score | |||

| Facials | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Steinberg and Walker Murdock sign | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Pectus carinatum | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Pectus excavatum or asymmetry of the thorax | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hollow foot | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Normal or flat foot | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Pneumothorax | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dural ectasia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Acetabular protrusion | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| US/UL Reduction or stroke/height ratio | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild scoliosis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thoracolumbar scoliosis or kyphosis | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Reduction of elbow extension | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin with stretch marks | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Myopia> 3 diopters | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mitral valve prolapses | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total systemic score | 5 | 6 | 4 |

|

No | No | No |

|

No | No | No |

| 1 = 2, aortic dilatation | 2 = 2, aortic dilatation | 2 = aortic dilatation and in his mother | |

| Clinical suspicion of the BH syndrome by score system | |||

| Appearance of ear helix | Wrinkled (3) | Wrinkled (3) | Elf (3) |

| Highly arched palate | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Retrognathia | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Joint contractures | Hands and feet (3) | Hands and feet (3) | Hands and feet (3) |

| Arachnodactyly | no | no | Yes (3) |

| dolichostenomelia | Yes (2) | Yes (2) | no |

| Pectus deformity | Yes (2) | no | no |

| Kyphoscoliosis | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | no |

| Mutation FBN-2 | No done | No done | Positive |

| Total score system | 13 | 11 | 11+ mutation |

| BH case | Sex | Age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Man | 30 | House painter by occupation. At the age of 28 he began to have dyspnea and chest tightness. He was evaluated by a cardiologist for recurrent oppressive chest pain, and was sent for evaluation to our center. On admission, at 29 years, he reported chest tightness. The echocardiographic study showed that he had aortic insufficiency, dilated left cavities, and decreased systolic function. The computed tomography also found severe destroxone convex scoliosis, aneurysm in the aortic root and ascending aorta. At the age of 30, he underwent Bentall and De Bono surgery. He was evaluated for suspected MFS; the only positive Ghent criterion was aortic dilation. He is currently alive, with 9 years of evolution. LVEF of 58%. |

| 2 | Man | 66 | A farmer, who began to have dyspnea when he was 53 years old and sought medical attention 6 years later. He was found to have a marfanoid habitus, aortic insufficiency attributed to aortic dilatation. A CT scan showed dilatation of the aortic root in the sinuses of Valsalva of 52 mm and an abdominal aortic aneurysm of 33 mm. He only met one of the Ghent criteria (aortic dilatation) and only met 6 of the systemic score. He had no other antecedents. His clinical characteristics showed a deep high-arched epicanthus palate, wrinkled ears, severe scoliosis and pectus carinatum. He underwent surgery using the Bentall and De bono technique. He is currently 66 years old and is stable. LVEF 62%. |

| 3 | Man | 36 | A financial stockbroker who practices at Parco. At the age of 25, on a trip to Israel, he presented acute abdominal pain that radiated to the pelvic cavity. A CT scan showed an abdominal aneurysm, and was treated with an endoprosthesis. He was evaluated for suspected MFS. The only relevant history was the death of his mother due to aortic rupture, but she died without a diagnosis. The patient only met one Ghent criterion (aortic dilatation) and was positive for mutation in the FBN-2 gene. The patient's clinical data included epicanthus, elf ears, CCA in the hands and feet, and a diagnosis of BH syndrome was concluded. Six years later, he presented a right femoral iliac dissection that was treated with an endoprosthesis. It was complicated by compartment syndrome treated with fasciotomy and finally had to be resolved with supracondylar amputation. Currently, his evolution is stable. LVEF 64% without aortic dilatation in the thorax. |

| CS | Sex | Age | Description |

| 1 | Man | 72 | Foreign farmer with no significant degenerative or cardiovascular history in 2014. At the age of 72 years, he began to have intense dominant pain, with straining and tenesmus. An ultrasound was performed in a private hospital, which showed an abdominal aneurysm. He was referred to our Institute and a CT scan was performed, which showed a ruptured infrarenal abdominal aneurysm with hemoperitoneum (Crawford-IV). Emergency surgery was performed. An 18 x 30 mm aortic graft was placed. The patient is alive and has a postoperative evolution of 10 years and two months. |

| 2 | Man | 52 | Foreign farmer with a history of arterial hypertension of 10 years of evolution dyslipidemia, alcoholism and positive smoking. His condition began at the age of 52. In 2015, after his work- day, he had intense precordial pain 7/10. In his place of origin, they performed a computed tomography that showed aortic dilatation and dissection. He was sent to our Institute and the MRI showed aortic dissection Stanford IIIB De DeBakey. Aortic dilatation of the descending thoracic abdominal aorta of 75 mm. The left ventricle showed concentric hypertrophy. Surgery was performed with aortic-thoracic abdominal replacement with revascularization of abdominal trunks. He died 24 hours later with refractory metabolic acidosis and acute kidney injury III. |

| 3 | Woman | 48 | Woman in housework occupation. In 2011 at the age of 40 she had dyspnea and was studied by a cardiologist who diagnosed her with significant aortic insufficiency and proposed aortic valve replacement. However, the patient postponed the surgery proposal. In 2016 the dyspnea had increased, she was found to have severe aortic insufficiency and a computed tomography found a bivalve aorta, dilation of the ascending aorta. Bentall and Bono surgery were performed. Current surgical survival is 8 years 4 months. |

| BH (n=3, median and min -max range) |

CS (n=3, median and min -max range) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38 (30–66) | 52 (48–72) |

| BMI (weight/height2) | 25 (19–27) | 31 (30–34) |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||

| DM | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) |

| SAH | 0 (0) | 2 (66.0) |

| Dyslipidemia | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Smoking | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Alcoholism | 0 (0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Serum biochemicals | ||

| Leukocytes (103/µL) | 6 (4.7–6.8) | 6.8 (0.9–9.0) |

| Lymphocytes (103/µL) | 1.9 (1.9–2) | 1.9 (1.6–2.2) |

| Neutrophils (103/µL) | 3.3 (2.2–4) | 5.9 (4.4–7.1) |

| Platelets (103/µL) | 194 (191–316) | 268 (158–307) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 15.9 (15.7–16.1)* | 11.4 (10.1–13.2) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 91 (90–100)* | 107 (80–264) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.80 (0.75–0.88)* | 0.83 (0.70–1.5) |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15.6 (11-4–20.6) | 17.3 (10.3–21.7) |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.4 (5.8–6.6) | 8.1 (6.2–8.4) |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.3 (4–4.7)* | 3.6 (2.4–3.6) |

| CT (mg/dL) | 181 (167–188) | 124 (98–146) |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 120 (114–120) | 81 (54–95) |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 41 (34–49) | 29 (16–34) |

| TG (mg/dL) | 104 (92–218) | 92 (80–127) |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.58 (0.30–0.75)* | 81 (6.5–143) |

| General characteristics of the aorta (mm) | ||

| Aortic ring | 31 (21–41) | 25 (24–30) |

| Valsalva sinuses | 52 (28–91)* | 46 (30–48) |

| Sino tubular junction | 38 (27–90)* | 38 (28–56) |

| Ascending aorta | 37 (29–46) | 30 (30–82) |

| Descending aorta | 33 (21–33)* | 50 (26–54) |

| Mitral Regurgitation (%) | 50 (30–60) | 54 (52–55) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).