Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rat Groups

2.2. Preparation of the HSL Infusion

2.3. Systolic Blood Pressure Measurement and Urine Collection

2.4. Quantification of Renal Function

2.5. Isolated and Perfused Kidney

2.6. Anatomical Changes in the Kidney by Histological Process

2.7. Determination of Polyphenols, Total Flavonoids and Anthocyanins in HSL infusion

2.8. Determination of Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant System Markers

2.8.1. NO3–/ NO2– Ratio

2.8.2. GSH/GSSG Ratio

2.8.3. Determination of Total Thiol Groups

2.8.4. Total Antioxidant Capacity

2.8.5. Superoxide Anion Detection

2.9. Markers of the Enzymatic Antioxidant System

2.9.1. GST, GPx, GR and TrxR Enzymes Activities

2.9.2. SOD Isoforms, CAT and Peroxidases Activities

2.9.3. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Activity (G6PD)

2.10. Nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NrF2)

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Guaranteed Analysis

3.2. General Characteristics and Markers of Kidney Function

3.3. Markers of the Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant System

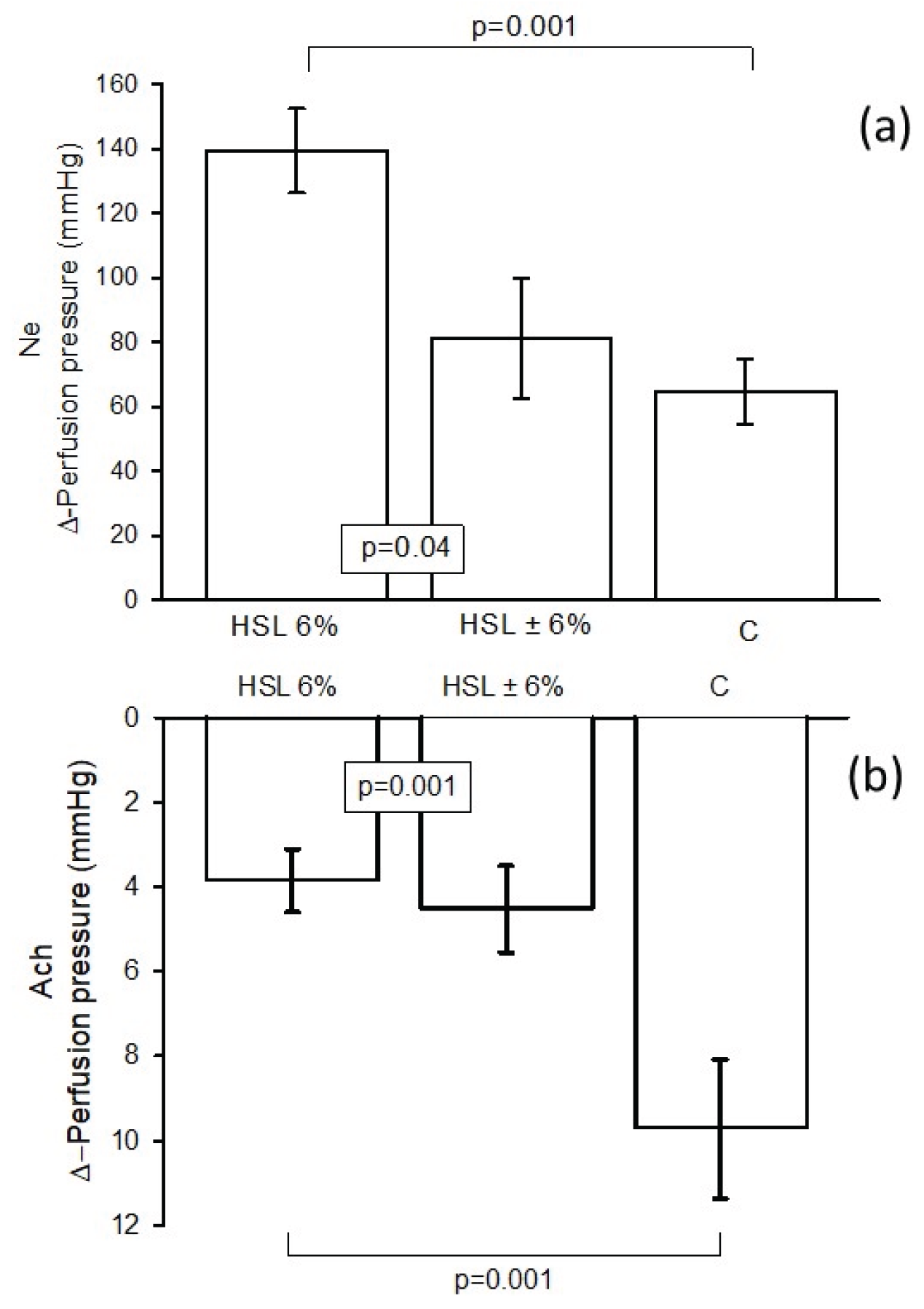

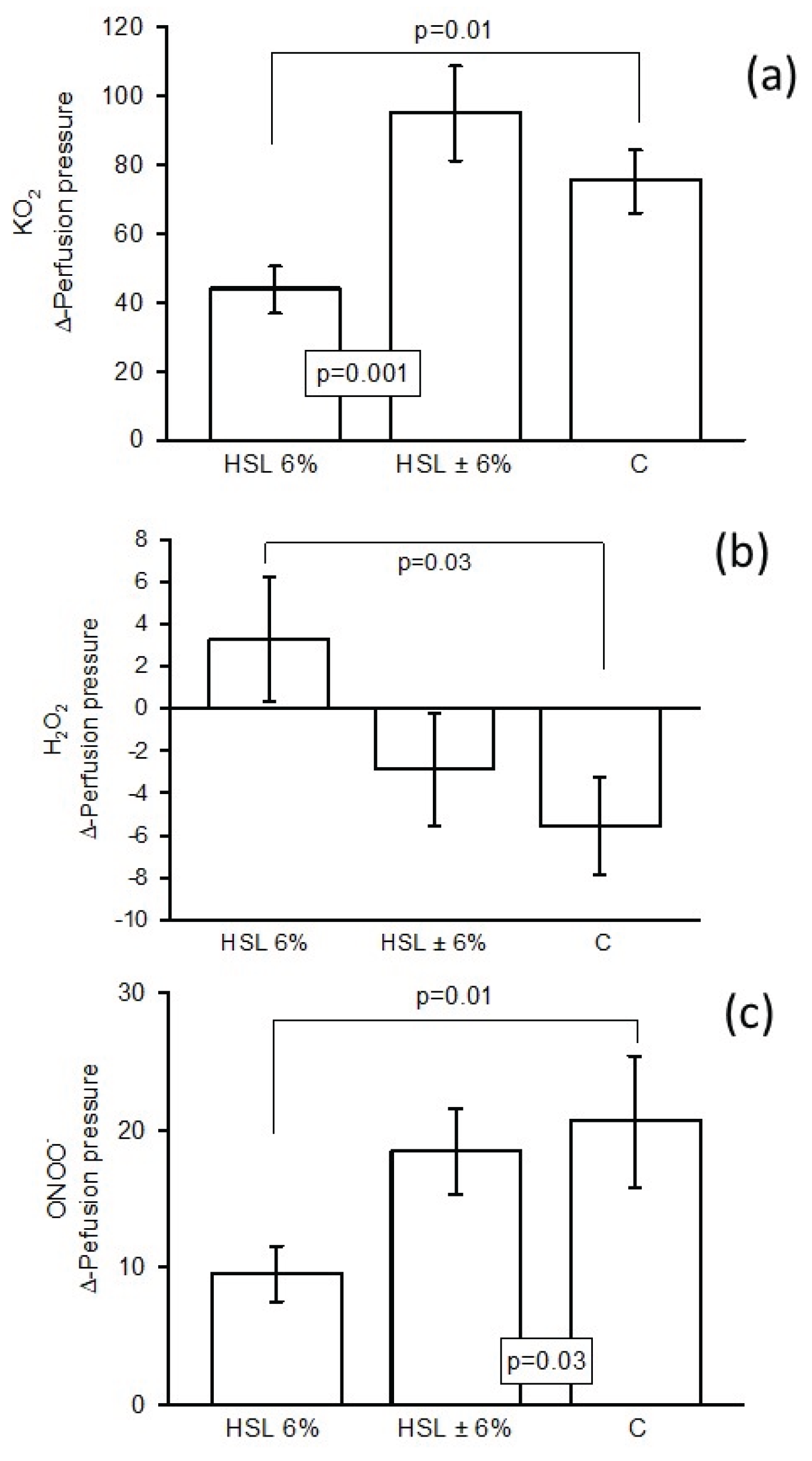

3.4. Changes in Δ-PP in the Kidney

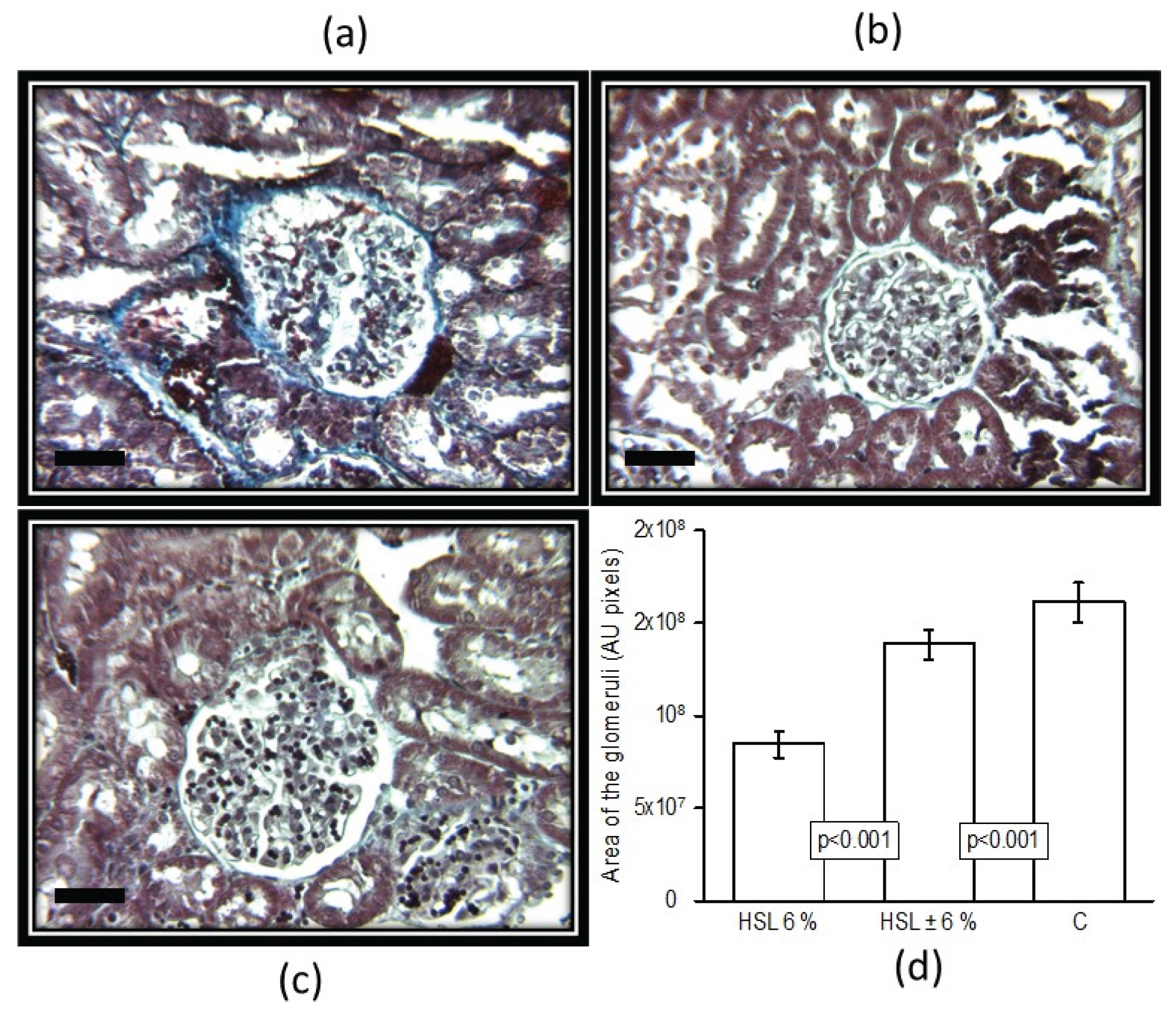

3.5. Anatomical Changes the Kidney

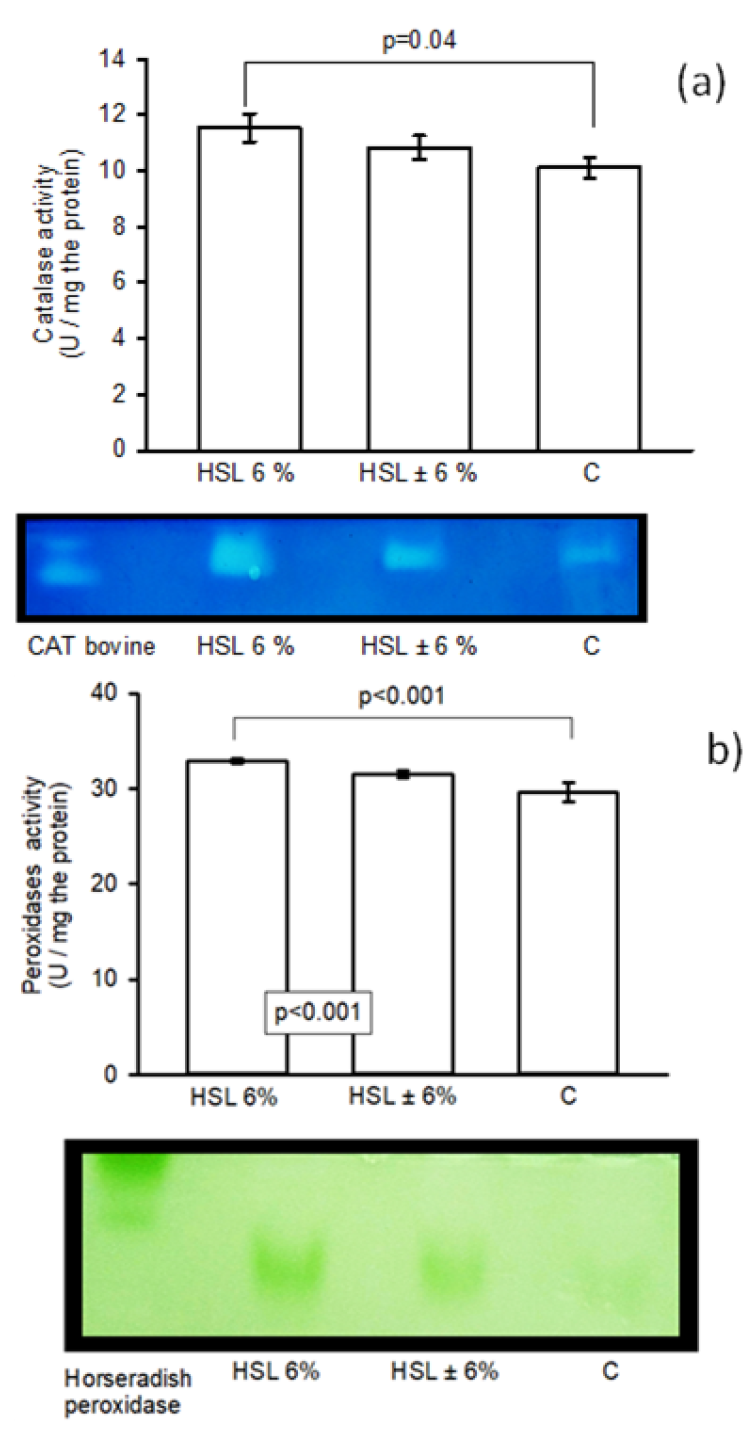

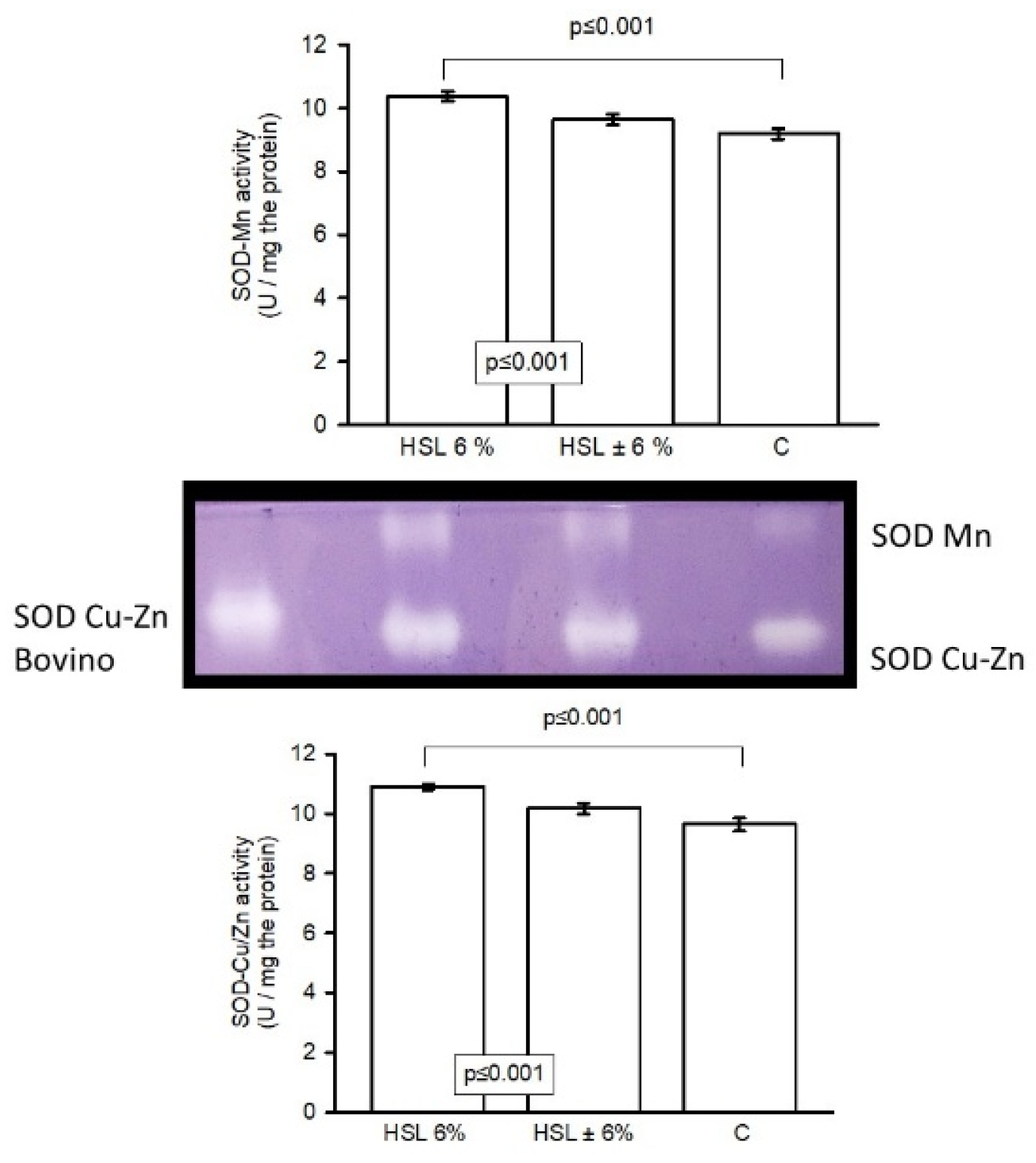

3.6. Enzyme Activity of the Enzymatic Antioxidant System in Native Polyacrylamide Gels

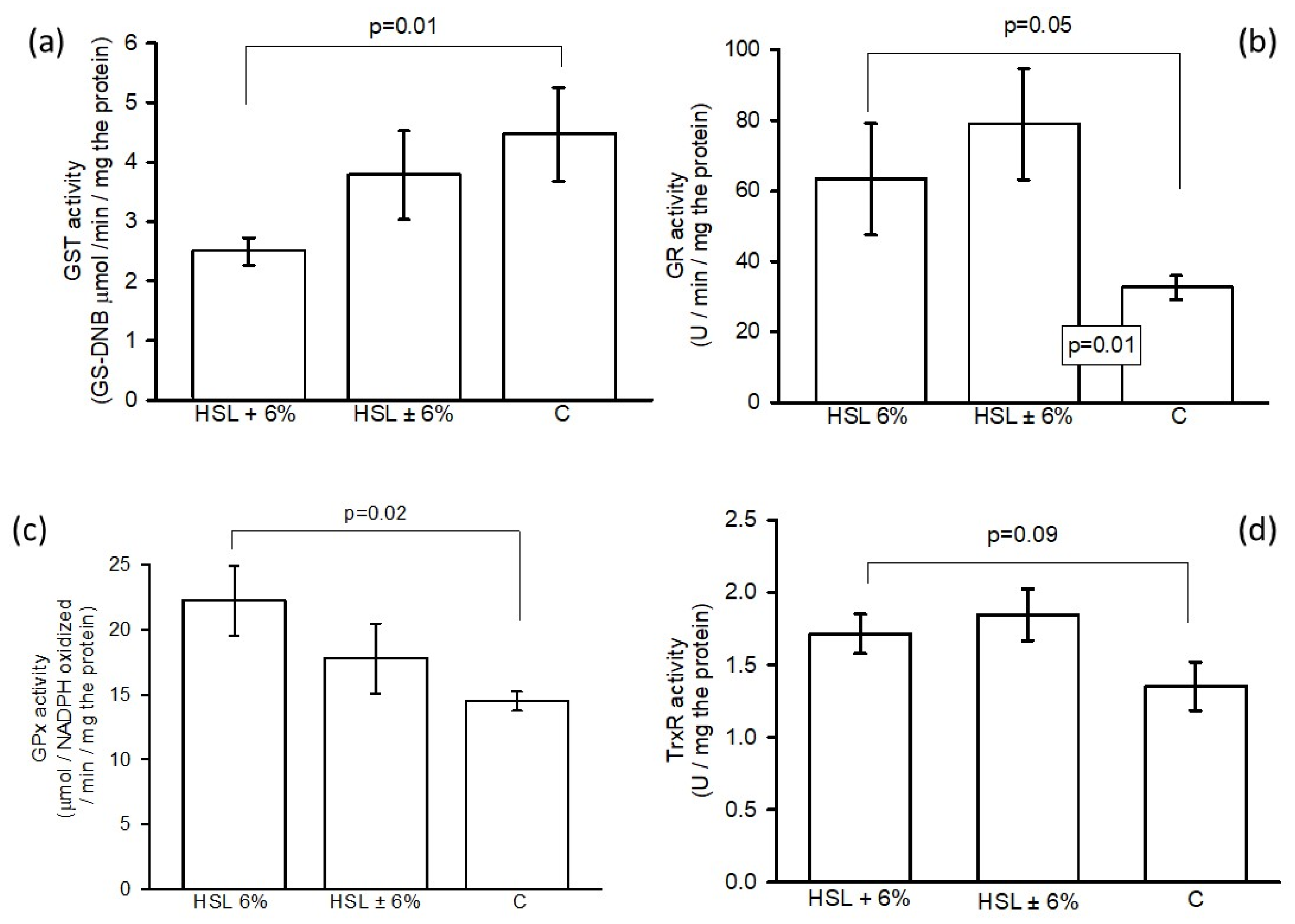

3.7. Activity of GSH-Using Enzymes in the Enzymatic Antioxidant System by Spectrophotometry

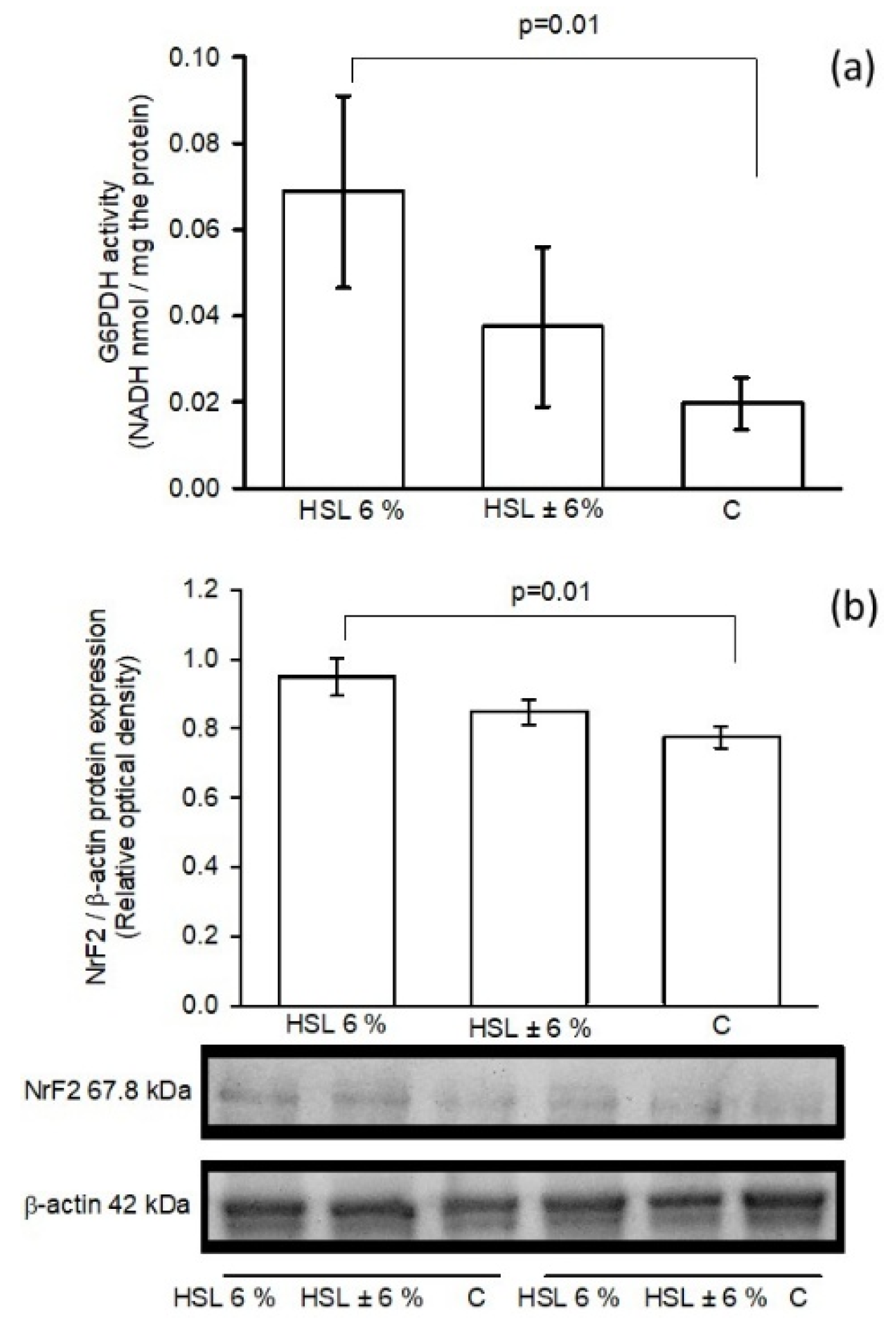

3.8. G6PD Activity and NrF2expression

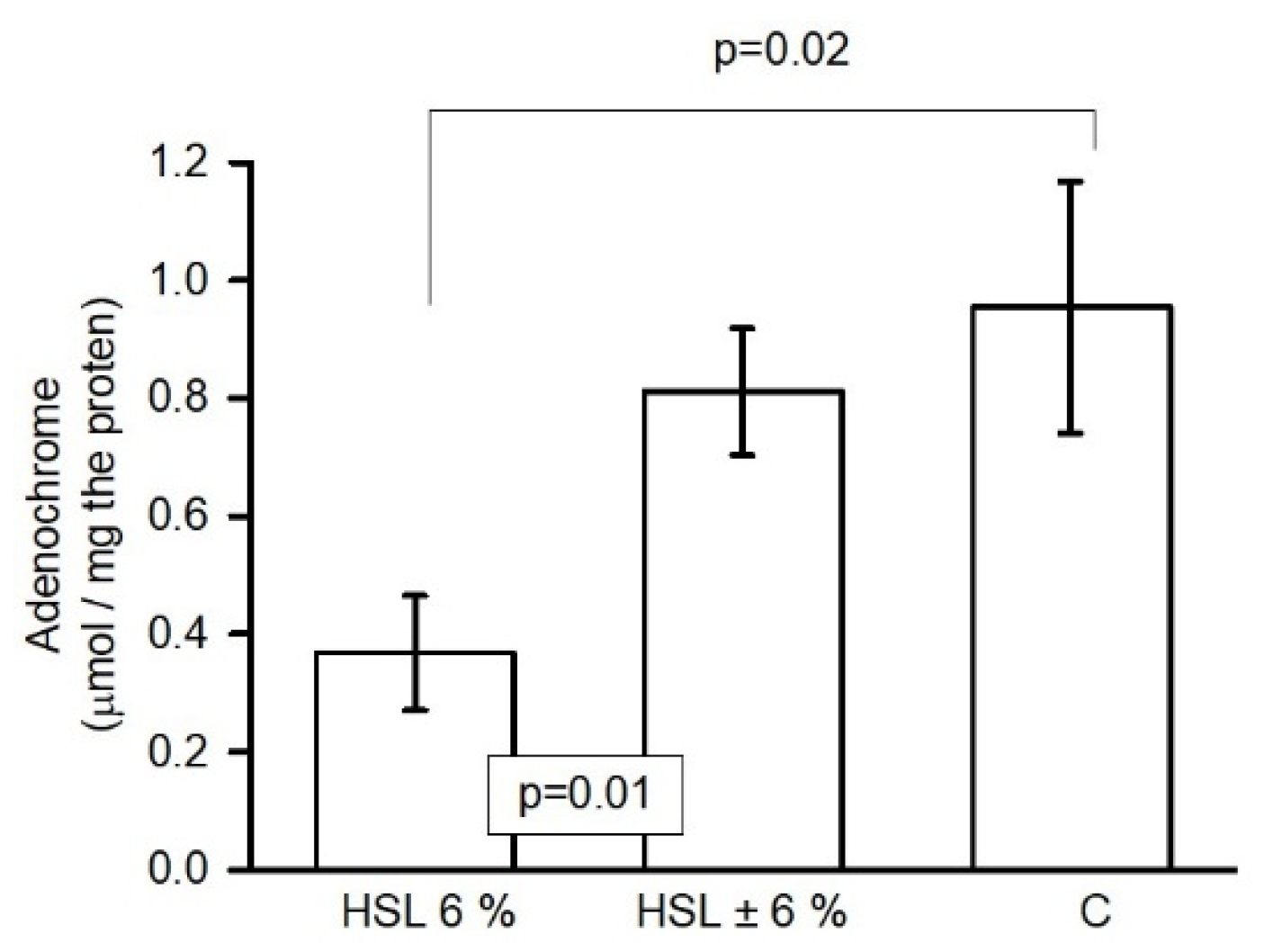

3.9. O2– Anion Quantification

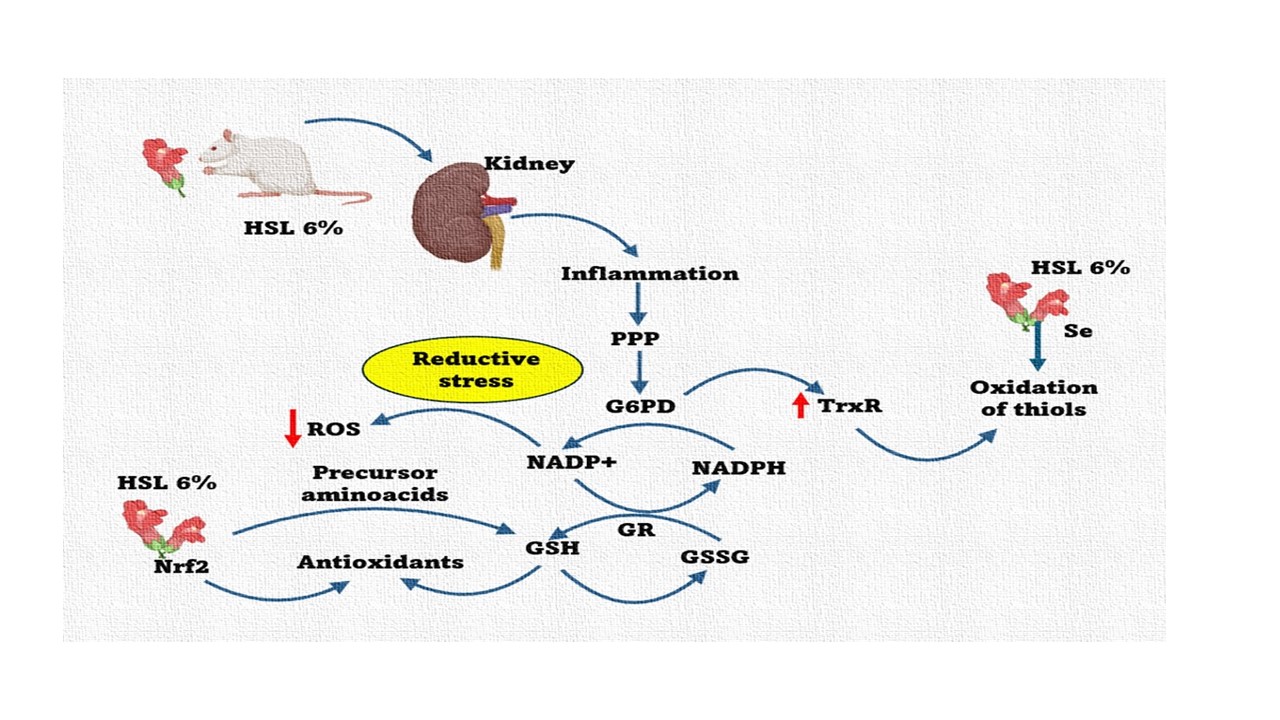

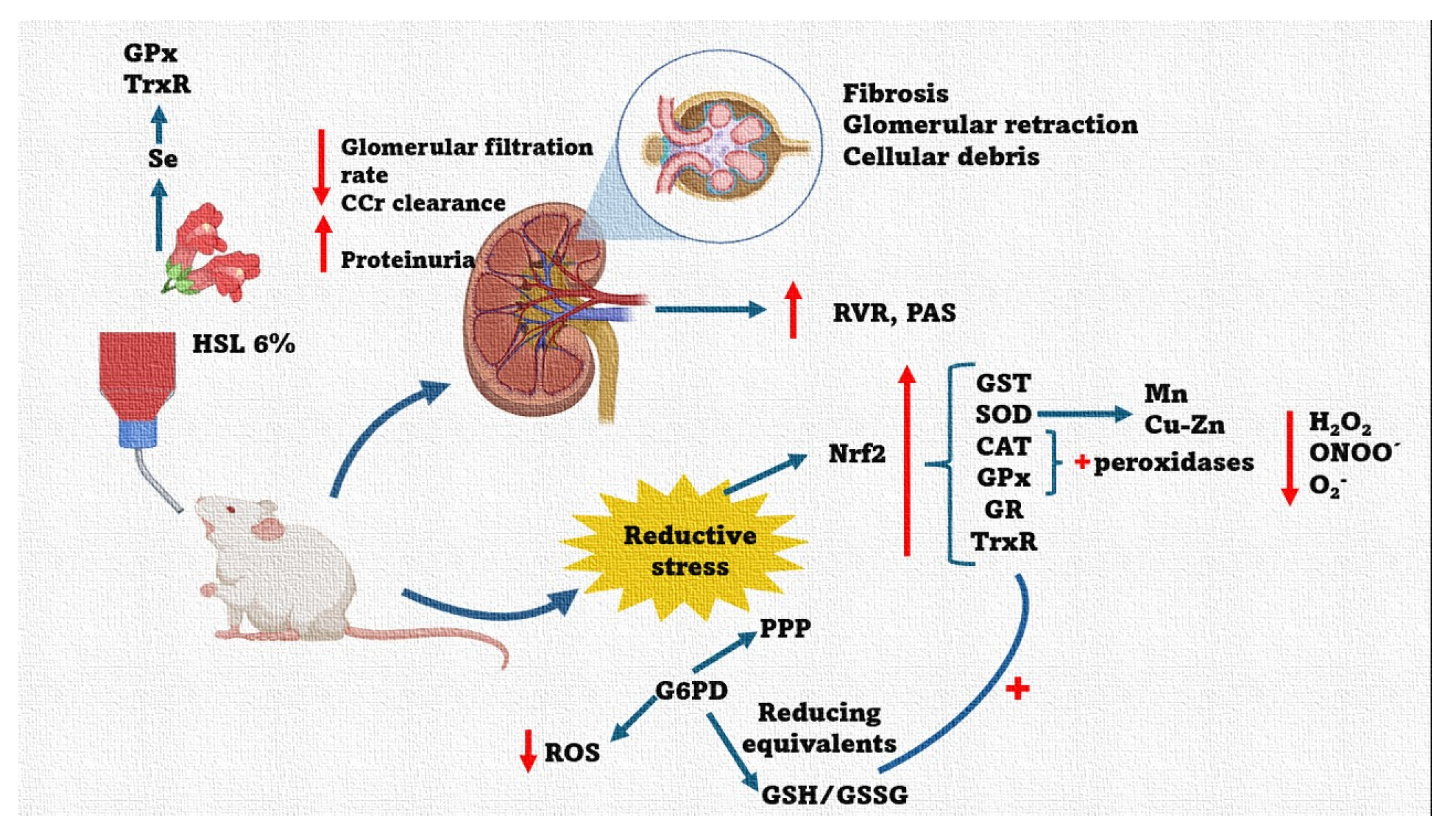

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| OS | Oxidative stress |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| O2– | Super oxide radical |

| O2 | Molecular oxygen |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| ONOO– | peroxynitrite |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| OH– | hydroxyl radical |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| RS | Reductive Stress |

| NADPH+ | reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADP+, | oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NAD | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| G6PD | glucose-6- dehydrogenase |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2 |

| SOD | super oxide dismutase |

| GST | glutathione-s-transferase |

| GR | Glutathione reductase |

| Cu-Zn | copper-zinc |

| Mn | manganese |

| TrxR | thioredoxin reductase |

| HSL | Hibiscus sabdariffa Linnaeus |

| Ne | norepinephrine |

| Ach | acetylcholine |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| SCr | serum creatinine |

| CCr | creatinine clearance |

| UCr | urinary creatinine |

| KO2 | potassium superoxide |

| PP | perfusion pressure |

| TAC | total antioxidant capacity |

| RVR | renal vascular resistance |

| PPP | pentose phosphate pathway |

| NO3–/NO2– | Nitrates and nitrites |

References

- Singh, S. Oxidative stress and sarcomeric proteins. Cir. Res. 2013, 112, 393–405. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, F.; Charles, A.; Schlagowski, A.; Bouitbir, J.; Bonifacio, A.; Piguard, F.; Krähenbühl, S.; Geny, B.; Zoll, J. Reductive stress impairs myoblast’s mitochondrial function and triggers mitochondrial hormesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015, 7, 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favier, A. Oxidative stress in human diseases. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2006, 64, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: a concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox. Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Soto, M.E.; Castrejón-Tellez, V.; Rubio-Ruiz, M.E.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Guarner-Lans, V. ; Oxidative, reductive, and nitrosative stress effects on epigenetics and on posttranslational modification of enzymes in cardiometabolic diseases. Oxid Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 8819719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Castrejón-Téllez, V.; Soto, M.E.; Rubio-Ruiz, M.E.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Guarner-Lans, V. Oxidative stress, plant natural antioxidants, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverne, Y.; Bogers, A.; Duncker, B.; Merkus, D. Reactive oxygen species and the cardiovascular system. Oxid Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhar, M.; Stamler, J. A central role for S-nitrosylation in apoptosis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2005, 7, 645–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, S.; Kang, S.; Jeong, W.; Chang, T.; Yang, K.; Woo, H. Intracellular messenger function of hydrogen peroxide and its regulation by peroxiredoxins. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2005, 17, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grune, T. Oxidants and antioxidative defense. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2002, 2, 61–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filaire, E.; Toumi, H. Reactive oxygen species and exercise on bone metabolism: friend or enemy? Joint. Bone. Spine. 2012, 79, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Rubio-Ruíz, M.E.; Soto, M.E.; Guarner-Lans, V. Nitrosative stress and Its association with cardiometabolic disorders. Molecules. 2020, 25, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Rubio-Ruiz, M.E. Reductive stress in inflammation-associated diseases and the pro-oxidant effect of antioxidant agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Limphong, P.; Pieper, J.; Liu, Q.; Rodesch, C.; Christians, E.; Benjamin, I. Glutathione-dependent reductive stress triggers mitochondrial oxidation and cytotoxicity. FASEB. J. 2012, 26, 1442–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, S.; Sun, H.; Liu, B.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.X. Recent findings in the regulation of G6PD and its role in diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 932154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, I.; Giambanco, I.; Minelli, A.; Donato, R. Nrf2 -Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. BBA. Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, Y.; Choi, B. Molecular and chemical regulation of the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Molecules. 1007. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Kathleen, K.; Shao-yu, C. Nrf2-Mediated transcripcional induction of antioxidant response in mouse embryos exposed to ethanol in vivo: Implications for the prevention of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2008, 10, 2023–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World. Allergy. Organ. J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohé, R.; Maiorino, M. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1830, 3289–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, V.; Carvalho, V. The thioredoxin system as a target for mercury compounds. Biochim. Biophys. acta. Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 129255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J. and Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 7: 2014; 66, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arnér, E. Focus on mammalian thioredoxin reductases-Important selenoproteins with versatile functions. Biochim. biophys acta. Gen. Subj. 2009, 1790, 495–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameritsch, P.; Singer, M.; Nuernbergk, C.; Rios, N.; Reyes, A.; Schmidt, K.; Kirsch, J.; Schneider, H.; Muller, S.; Pogoda, K.; Cui, R.; Kirchner, T.; Wit, C.; Lange-Sperandio, B.; Pohl, U.; Conrad, M.; Radi, R.; Beck, H. The mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase system (TrxR2) in vascular endothelium controls peroxynitrite levels and tissue integrity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021, 118, e1921828118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vararattanavech, A.; Ketterman, A.J. Multiplerolesof glutathionebinding-siteresiduesof glutathione s-transferase. Protein. Pept. Lett. 2003, 10, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deponte, M. Glutathione catalysis and the reaction mechanisms of glutathione-dependent enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1830, 3217–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, P.J. Peroxidases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2000, 129, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of catalase in oxidative stress- and age-associated degenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 9613090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosz, G. Non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity assays. Limitations of use in biomedicine. Free. Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisik, M.; Alisik, T.; Nacir, B.; Neselioglu, S.; Genc-Isik, I.; Koyuncu, P.; Erel, O. Erythrocyte reduced/oxidized glutathione and serum thiol/disulfide homeostasis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Biochem. 2021, 94, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitka, O.; Skalickova, S.; Gumulec, J.; Masarik, M.; Adam, V.; Hubalek, J.; Trnkova, L.; Kruseova, J.; Eckschlager, T.; Kizek, R. Redox status expressed as GSH:GSSG ratio as a marker for oxidative stress in paediatric tumour patients. OncoL. lett. 2012, 4, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMartino, A.; Kim-Shapiro, D.; Patel, R.; Gladwin, M. Nitrite and nitrate chemical biology and signaling. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltz, P.; Escobar, D.; Botero, A.; Zuckerbraun, B. Nitrate/Nitrite as critical mediators to limit oxidative injury and inflammation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2015, 23, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baños, G.; Pérez-Torres, I.; El Hafidi, M. Medicinal agents in the metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents. Med. Chem. 2008, 6, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Ruiz-Ramírez, A.; Baños, G.; El-Hafidi, M. Hibiscus sabdariffa Linnaeus (Malvaceae), curcumin and resveratrol as alternative medicinal agents against metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents. Med. Chem. 2013, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanou, A.; Konate, K.; Dakuyo, R.; Kabore, K.; Sama, H.; Dicko, M.H. Hibiscus sabdariffa: Genetic variability, seasonality and their impact on nutritional and antioxidant properties. PLoS. One. 2022, 17, e0261924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletajew, S.; Antoniewicz, A.A.; Borówka, A. Kidneyr emoval: the past, presence, and perspectives: a historical review. Urol. J. 2010, 7, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Kishi, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Ichimura, T.; Brooks, C.R. In Human reconstructed kidney models. In Vitro. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2021, 57, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Hohl, M.; Elliot, A.D.; Lau, D.H.; Mahfoud, F.; Esler, M.D.; Sander, P.; Böhm, M. Modulation of renal sympathetic innervation: recent insights beyond blood pressure control. Clin Auton Res. 2018, 28, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sata, Y.; Head, G.A.; Denton, K.; May, C.N.; Schlaich, M.P. Role of Sympathetic Nervous System and Its Modulation in Renal Hypertension. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Guarner, V.; El Hafidi, M.; Baños, G. ; Baños, G. Sex hormones, metabolic syndrome and kidney. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 1694–705. [Google Scholar]

- BenGershom, E. Screening for albuminuria: A case for estimation of albumin in urine. Clin Chem. 1975, 21, 1795–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, N.J. The Bradford method for protein quantitation Methods. Mol. Biol. 1994, 32, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Z.; Tang, M.; Wu, J. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food. Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.; Wrolstad, R. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the Ph Differential Method: collaborative study. J. AOAC. Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikas, D. Analysis of nitrite and nitrate in biological fluids by assays based on the Griess reaction: Appraisal of the Griess reaction in the L-arginine/nitric oxide area of research. J. Chromatogr. B. Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci. 2007, 851, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griess, J. Patents Relating to Chemistry:213,563. And 213,564 Coloring matters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1879, 1879, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Kode, A.; Biswas, S. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 6, 3159–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, O.; Neselioglu, S. A novel and automated assay for thiol/disulphide homeostasis. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 47, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Soto, M.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Díaz-Díaz, E.; Soria-Castro, E.; Rubio-Ruíz, M.; Guarner-Lans, V. Oxidative stress in plasma from patients with Marfan syndrome is modulated by deodorized garlic. Preliminary findings. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5492127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.M.; Silva, R.; Ferreira, L.M.; Branco, P.S.; Carvalho, F.; Bastos, M.L.; Carvalho, R.A.; Carvalho, M.; Remião, F. Oxidation process of adrenaline in freshly isolated rat cardiomyocytes: formation of adrenochrome, quinoproteins, and GSH adduct. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Loscalzo, J. Metabolic responses to reductive stress. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2020, 32, 1330–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedeek, M.; Nasrallah, R.; Touyz, R.M.; Hébert, R.L. NADPH Oxidases, Reactive Oxygen Species, and the Kidney: Friend and Foe. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenov, M.; Lubomirov, L.; Grisk, O.; Avtanski, D.; Mitrokhin, V.; Sazdova, I.; Keremidarska-Markova, M.; Danailova, Y.; Nikolaev, G.; Konakchieva, R.; Gagov, H. Oxidative stress, reductive stress and antioxidants in vascular pathogenesis and aging. Antioxidants. (Basel). 2023, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; El Hafidi, M.; Pavón, N.; Infante, O.; Avila-Casado, M.C.; Baños, G. Effect of gonadectomy on the metabolism of arachidonic acid in isolated kidney of a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2010, 59, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Pech, L.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Elena Soto, M.; Díaz-Díaz, E.; Pérez-Torres, I. Alteration of the aortic vascular reactivity associated to excessive consumption of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linnaeus: Preliminary findings. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e20020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Pech, L.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Soto, M.E.; Díaz-Díaz, E.; Caballero-Chacón, S.; Díaz-Torres, R.; Rodríguez-Fierros, F.L.; Pérez-Torres, I. Excessive Consumption Hibiscus sabdariffa L. Increases inflammation and blood pressure in male wistar rats via high antioxidant capacity: The preliminary findings. Cells. 2022, 11, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nlandu, K.S.; Dizin, E.; Sossauer, G.; Szanto, I.; Martin, P.Y.; Feraille, E.; Krause, K.H. de Seigneux, S.J. NADPH-oxidase 4 protects against kidney fibrosis during chronic renal injury. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 23, 1967–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. Responses to reductive stress in the cardiovascular system. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 109, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretón, R.; Lamas, S. Hydrogen peroxide signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Redox. Biol. 2014, 2, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touyz, R.; Ríos, F.; Lopes, R.; Neves, K.; Camargo, L. Montezano, A. Oxidative stress: a unifying paradigm in hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kaufman, R.J. The impact of the unfolded protein response on human disease. J. Cell. Biol. 2012, 197, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gago, B.; Lundberg, J.O.; Barbosa, R.M.; Laranjinha, J. Red wine-dependent reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide in the stomach. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacenza, L.; Zeida, A.; Trujillo, M.; Radi, R. The superoxide radical switch in the biology of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1881–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nose F, Ichikawa T, Fujiwara M, Okayasu I. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 expression in lymphocytic thyroiditis and thyroid tumors: significant correlation with inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002, 117, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Soto, M.E.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Soria-Castro, E. The possible role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in the SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cells. 2022, 11, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, C.; Romacho, T.; Azcutia, V.; Villalobos, L.; Fernández, E.; Bolaños, J.; Moncada, S; Sánchez-Ferrer, C. Inflammation, glucose, and vascular cell damage: the role of the pentose phosphate pathway. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2016, 15, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, T.; Raji, H.; Adeleye, A.; Adigun, N.; Giwa, O.; Ojewuji, O.; Oladiji, A. Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx palliates insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and oxidative rout in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome rats. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2016, 96, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrick, M.; Didion, S.; Lynch, C.; Dayal, S.; Lentz, S.; Faraci, F. Role of hydrogen peroxide and the impact of the glutathione peroxidase-1 in regulation of cerebral tone vascular. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2009, 29, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P. Selenium accumulation by plants. Ann. Bot. 2016, 117, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, S.; Dharmaraj, S. Selenium and selenoproteins: it’s role in regulation of inflammation. Inflammopharmacology. 2020, 28, 667–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Holmgren, A. Glutathione and glutaredoxin act as a backup of human thioredoxin reductase 1 to reduce thioredoxin 1 preventing cell death by aurothioglucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 38210–38219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajka-Kuzniak, V.; Szaefer, H.; Baer-Dubowska, W. Hepatic and extrahepatic expression of glutathione S-transferase isozymes in mice and its modulation by naturally occurring phenolic acids. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 25, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayeshi, R.; Mutingwende, I.; Mavengere, W.; Masiyanise, V.; Mukanganyama, S. The inhibition of human glutathione S- transferases activity by plant polyphenolic compounds ellagic acid and curcumin. Food. Chem. To.

- Terada, A.; Yoshida, M.; Seko, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshida, K.; Nakada, M.; Nakada, K.; Echizen, H.; Ogata, H.; Rikihisa, T. Active oxygen species generation and cellular damage by additives of parenteral preparations: Selenium and sulfhydril compounds. Nutr. J. 1999, 15, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, J.P.; Cramer, C.J. Direct examination of H2O2 activation by a heme peroxidase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7802–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, E.; Buch, T.; Hermann-Josef, G. Myeloperoxidase in kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisa-Alvarez, A.; Soto, M.; Guarner-Lans, V.; Camarena-Alejo, G.; Franco-Granillo, J.; Martínez-Rodríguez, E.; Gamboa, R.; Manzano, L.; Pérez-Torres, I. Usefulness of antioxidants as adjuvant therapy for septic shock: A randomized clinical trial. Medicina. 2020, 56, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Dalton, T.P.; Nebert, D.W.; Shertzer, H.G. Glutathione redox state regulates mitochondrial reactive oxygen production. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 25305–25312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. Responses to Reductive Stress in the Cardiovascular System Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 109, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | HSL 6% | HSL ± 6% | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking water (mL/24 h) | 13.4 ± 1.3** | 29.8 ± 2.7 | 25.4 ± 2.6 |

| Weight of the right kidney (g) | 1.2 ± 0.05 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | 1.2 ± 0.03 |

| Urine (mL/24 h) | 7.7 ± 0.8* | 21.1 ± 1.8 | 18.7 ± 4.5 |

| CCr (mL/min) | 0.05 ± 0.015** | 0.93 ± 0.29* | 1.61 ± 0.86 |

| Albuminuria (mg/mL) | 2.12 ± 0.30** | 0.98 ± 0.17 | 1.38 ± 0.26 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 145.2 ± 4.4** | 126.6 ± 2.1* | 118.7 ± 2.2 |

| Body weight (g) | 351.7 ± 17.0 | 341.0 ± 6.3 | 324.6 ± 6.9 |

| Variables (mg the protein) | HSL 6% | HSL ± 6% | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSH/GSSG ratio (μM) | 0.024 ± 0.003* | 0.023 ± 0.002† | 0.016 ± 0.002 |

| TAC (nM) | 148.3 ± 21.9** | 136.6 ± 12.2* | 100.9 ± 8.4† |

| NO3–/NO2– ratio (nM) | 0.19 ± 0.01** | 0.06 ± 0.02** | 0.04 ± 0.01† |

| Thiols (μM) | 74.6 ± 35.8** | 120.2 ± 10.5** | 142.4 ± 30.6† |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).