Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

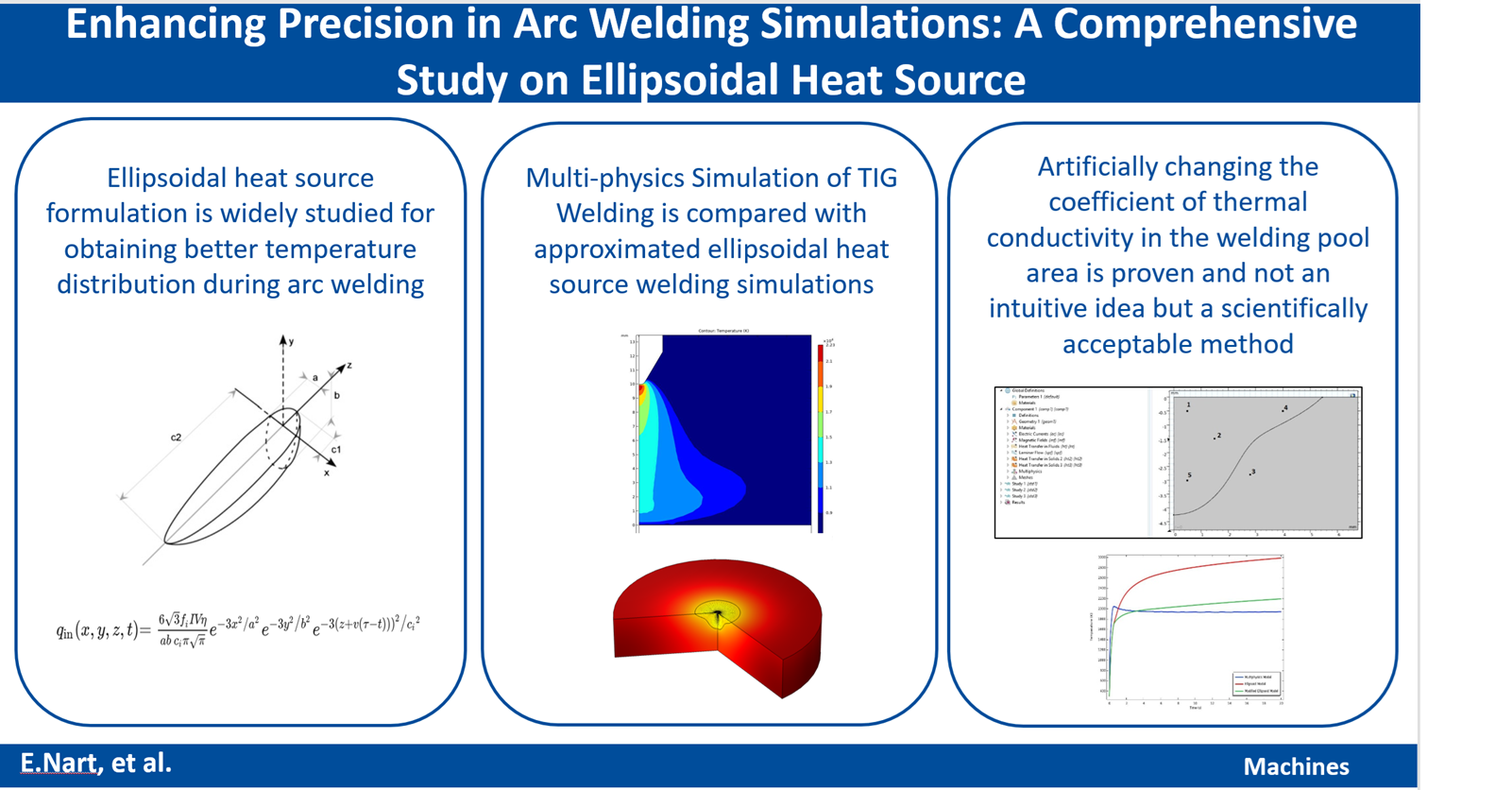

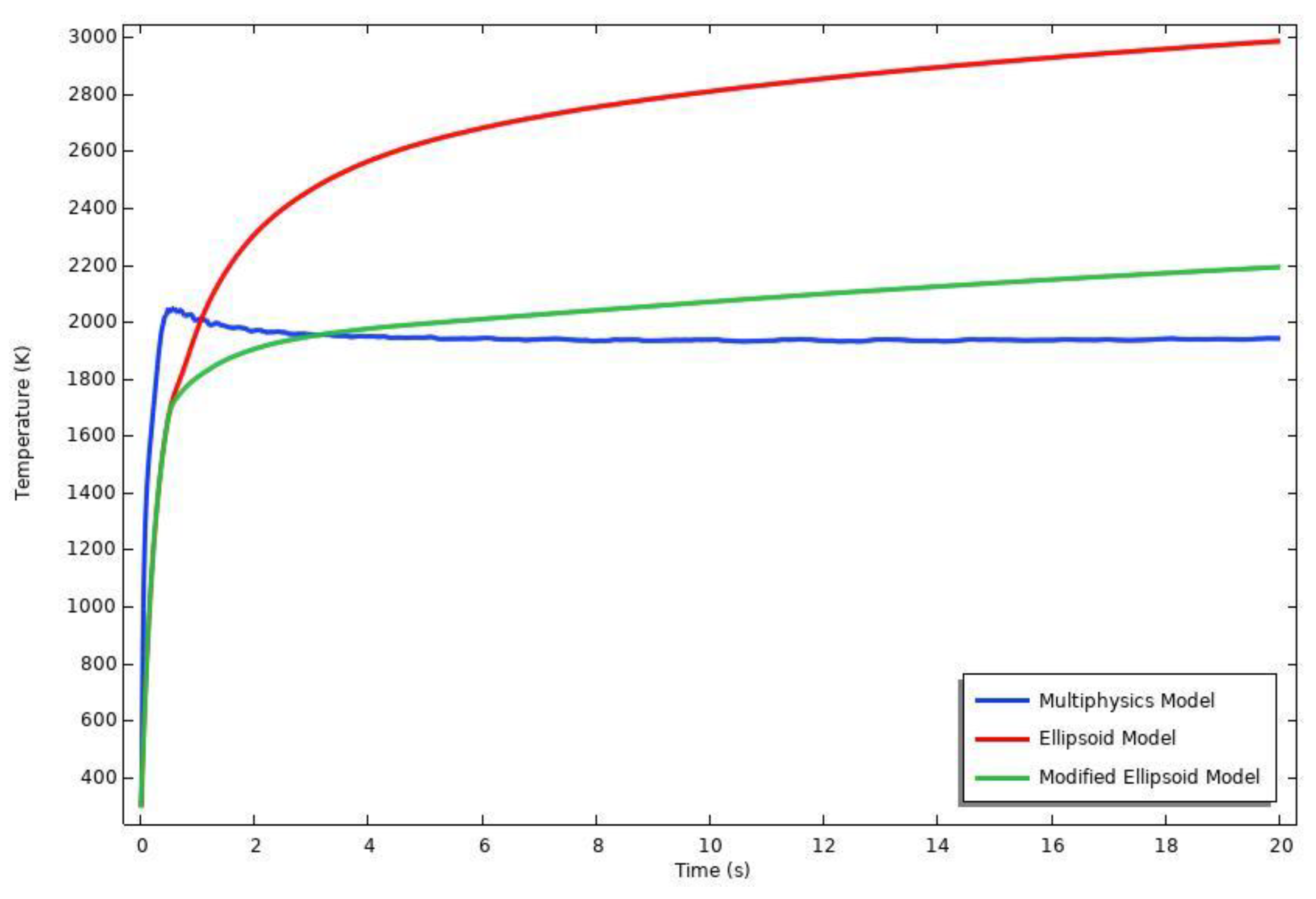

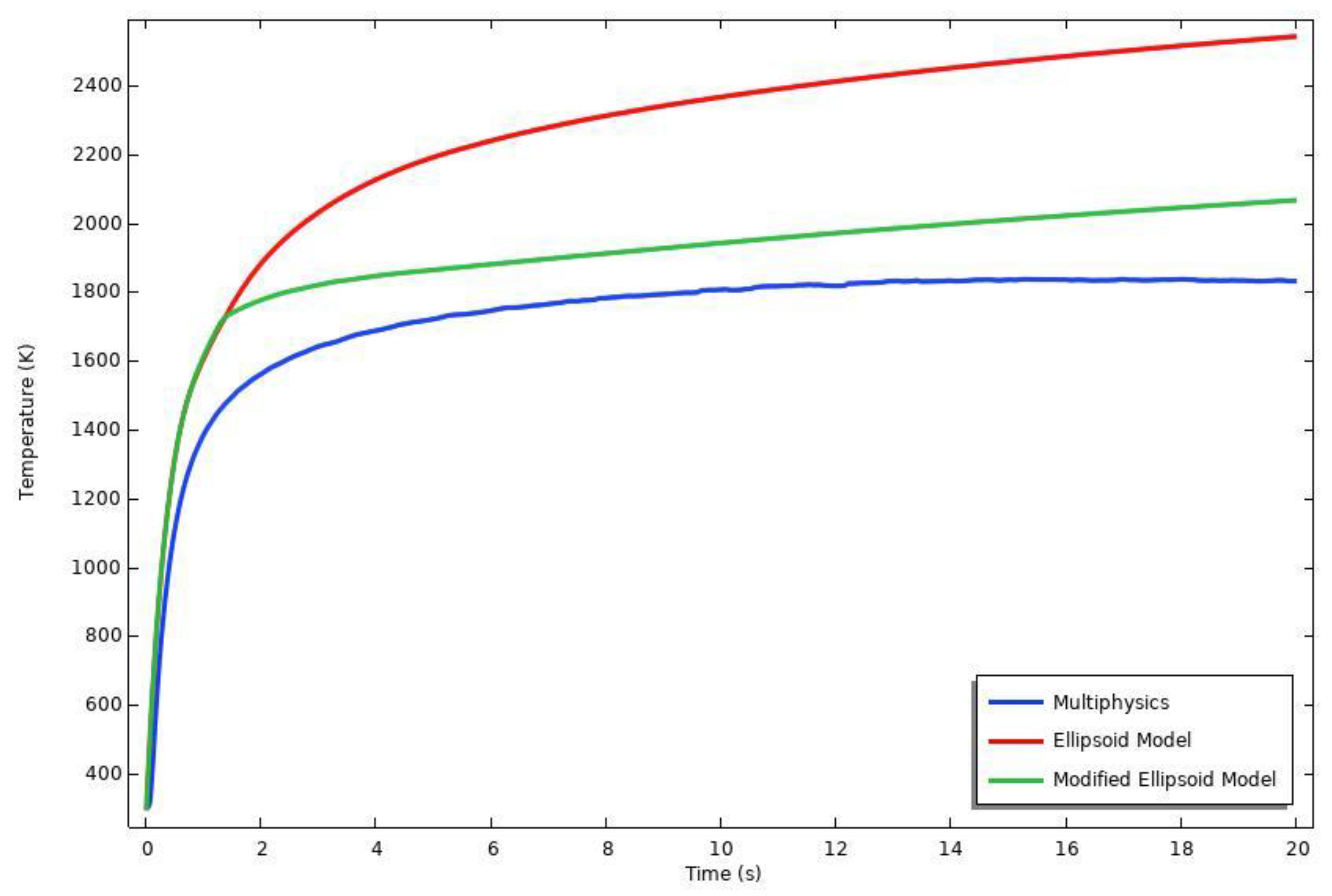

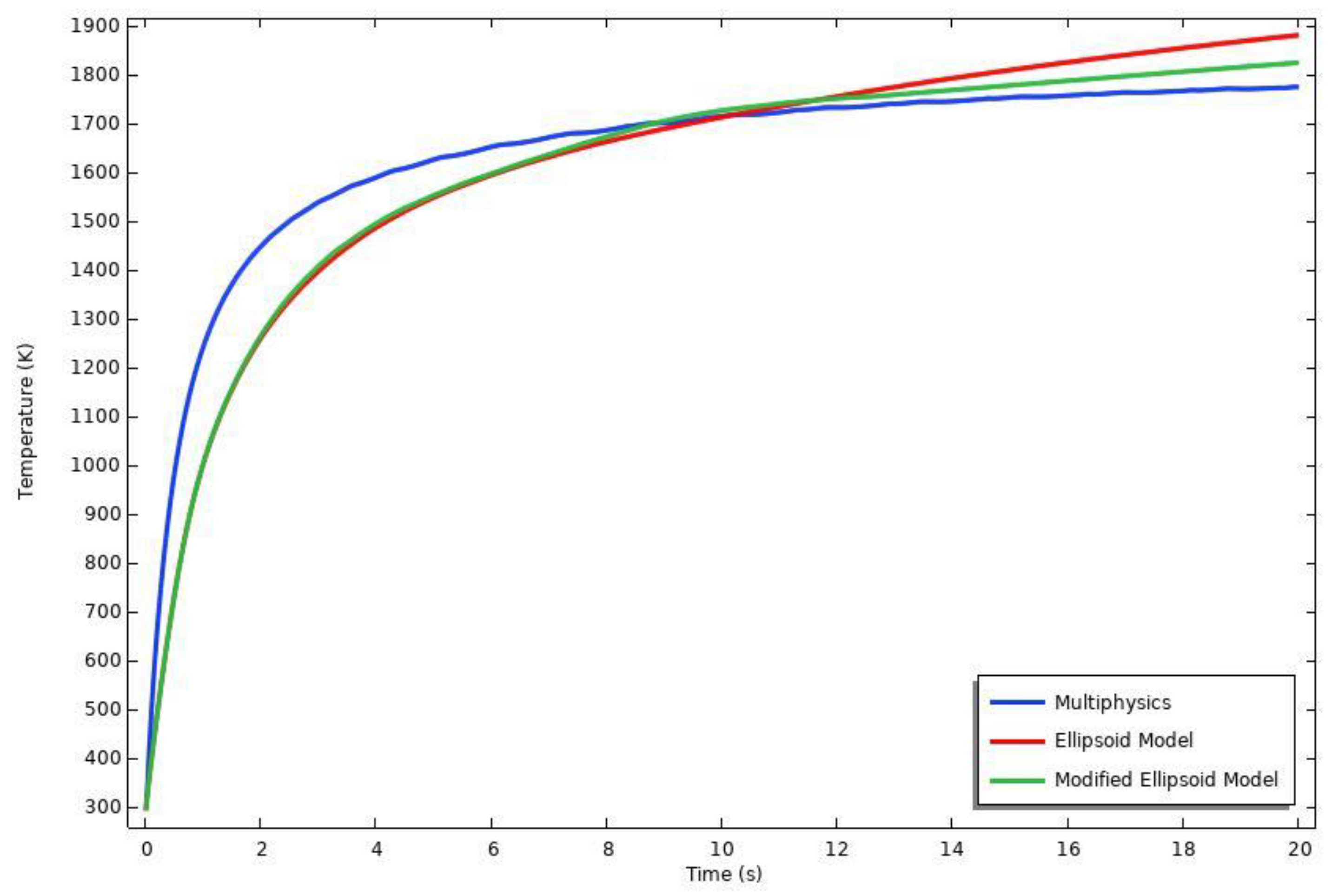

Arc welding is a complex multi-physics process, and its finite element simulation requires significant computational resources to determine temperature distributions in engineering problems accurately. Engineers and researchers aim to achieve reliable results from finite element analysis while minimizing computational costs. This research extensively studies the application of conventional ellipsoidal heat source formulation to obtain improved temperature distribution during arc welding for practical applications. Approximated ellipsoidal heat source model, which artificially modifies the coefficient of thermal conductivity in the welding pool area to simulate stirring effects, (Modified Ellipsoidal Model) is shown to be scientifically valid by comparing its results with those of Comsol's multi-physics arc welding models. The results show that, in comparison to the conventional ellipsoidal model, the temperature distributions obtained using the modified ellipsoidal model closely approach those from multi-physics simulations. In particular, the temperature history in the middle of the weld pool significantly changes and approaches the multiphysics solutions. Additionally, several points near the heat-affected zone were analyzed, and both ellipsoidal methods produced similar temperature histories until the metal melted. After melting, the modified ellipsoidal method gradually aligns more closely with the multiphysics solution. Additionally, both ellipsoidal methods produce similar temperature histories at points within the heat-affected zone.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Formulation and Governing Equations

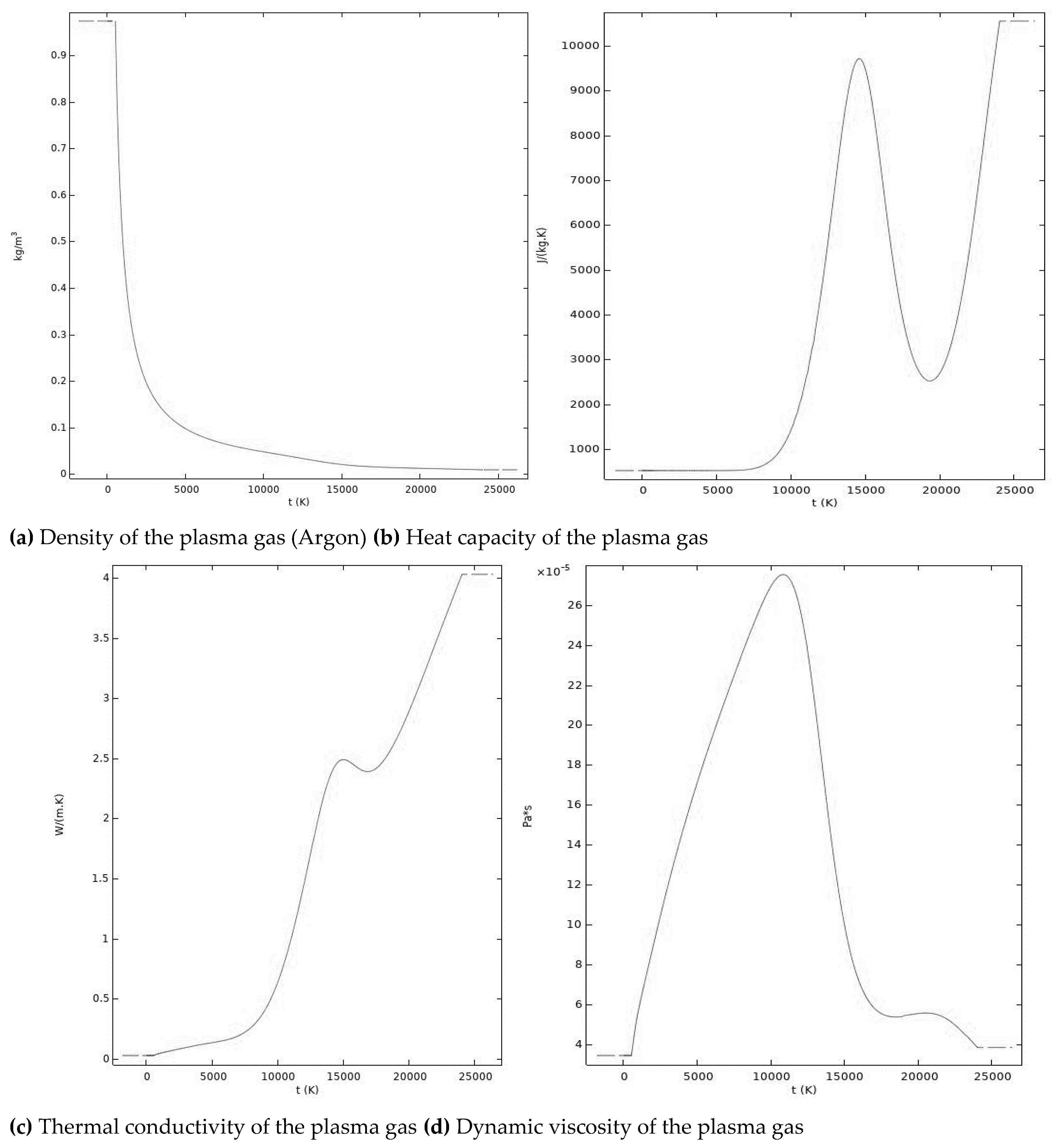

2.1. Equation for Thermal Plasma Modeling

- The arc is in Local thermodynamics equilibrium (LTE)

- Axisymmetric Spot GTA welding is assumed

- Pure argon is used and the metal vapors are not considered.

- Gas plasma is incompressible and the flow is laminar.

- Boussinesq approximation is not assumed in plasma.

Electrode and Anode Surfaces

2.2. Equation for Weld Pool Modeling

- Axisymmetric Spot GTA welding is assumed

- Metal flow in weld pool is laminar.

- The surface tension coefficient is dependent on both temperature and sulfur content.

- The latent heat of fusion is also taken into account.

- Boussinesq approximation is assumed in weld pool.

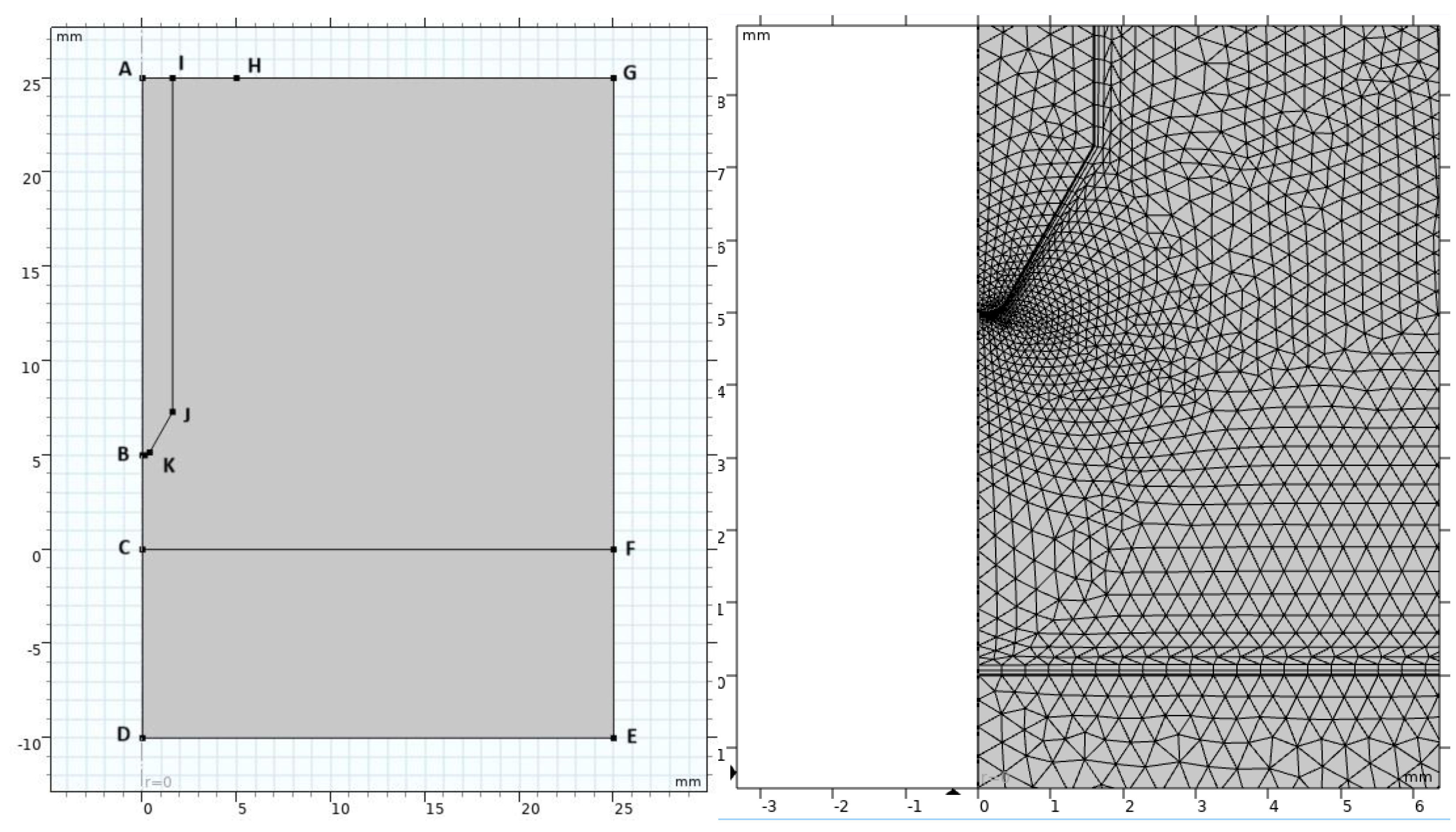

3. Computational Domain and Initial Conditions

3.1. The Free Surface Deformation

3.2. The Liquid/Surface Interface

3.3. Initial Conditions in Arc Plasma Region

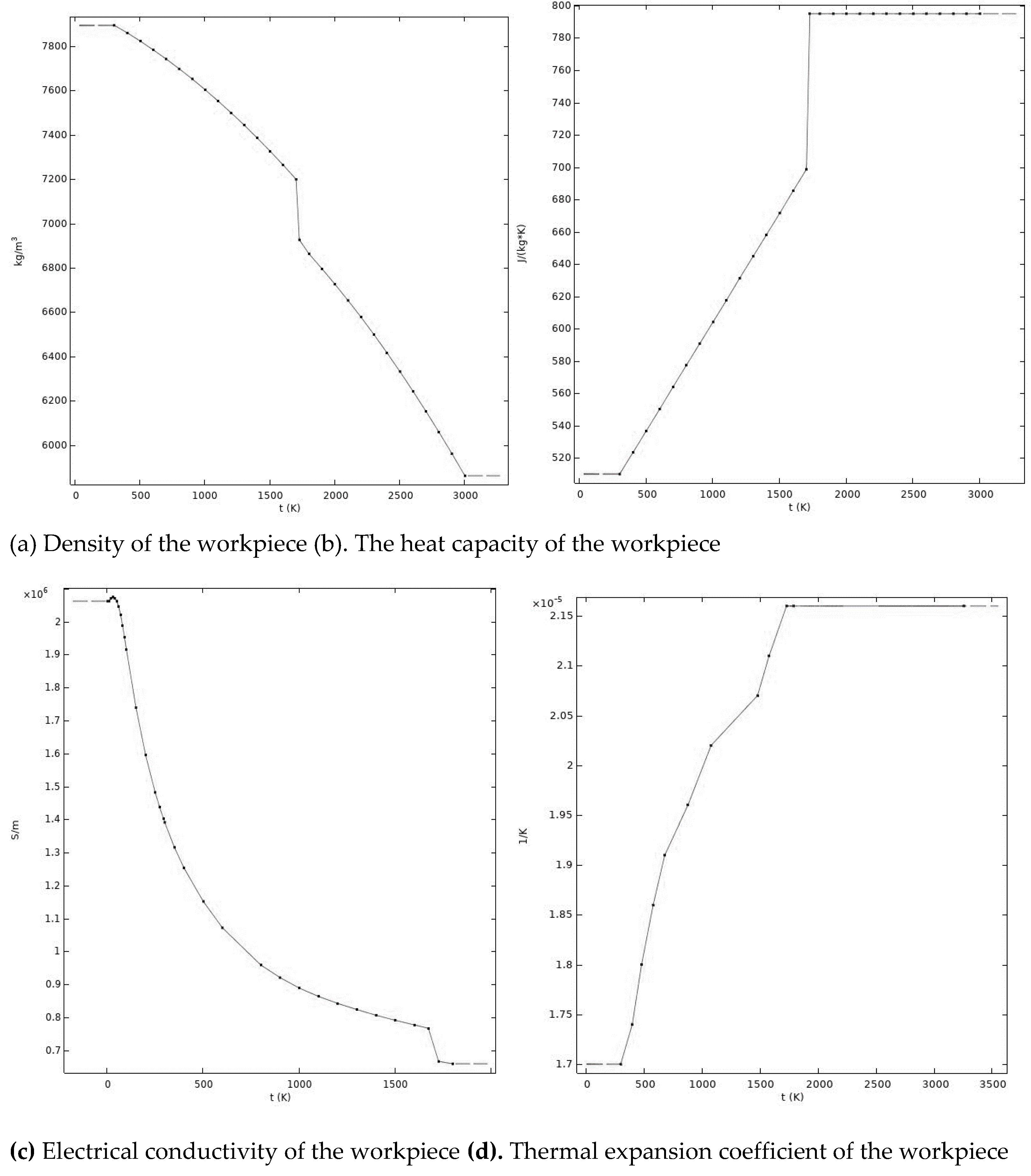

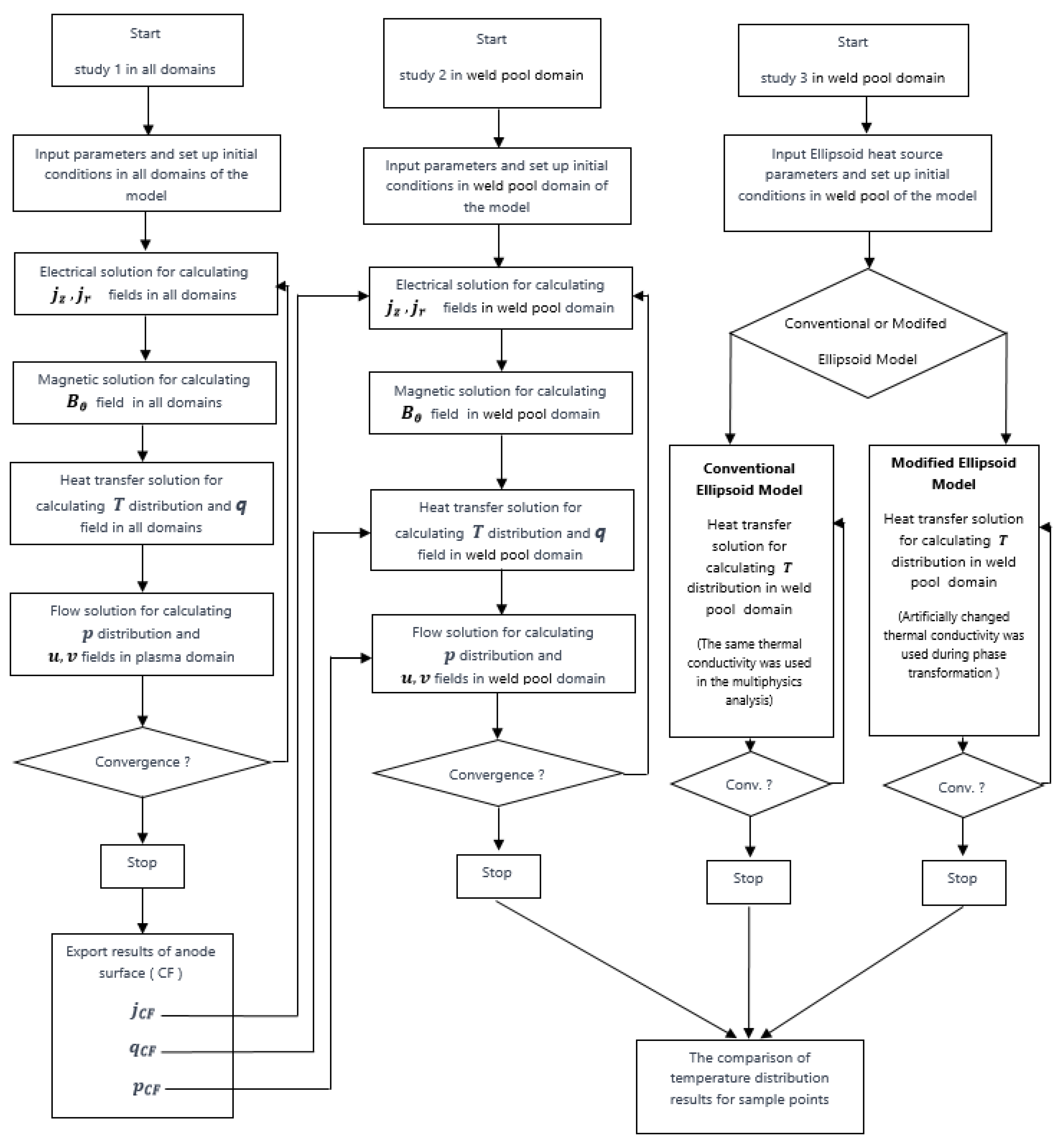

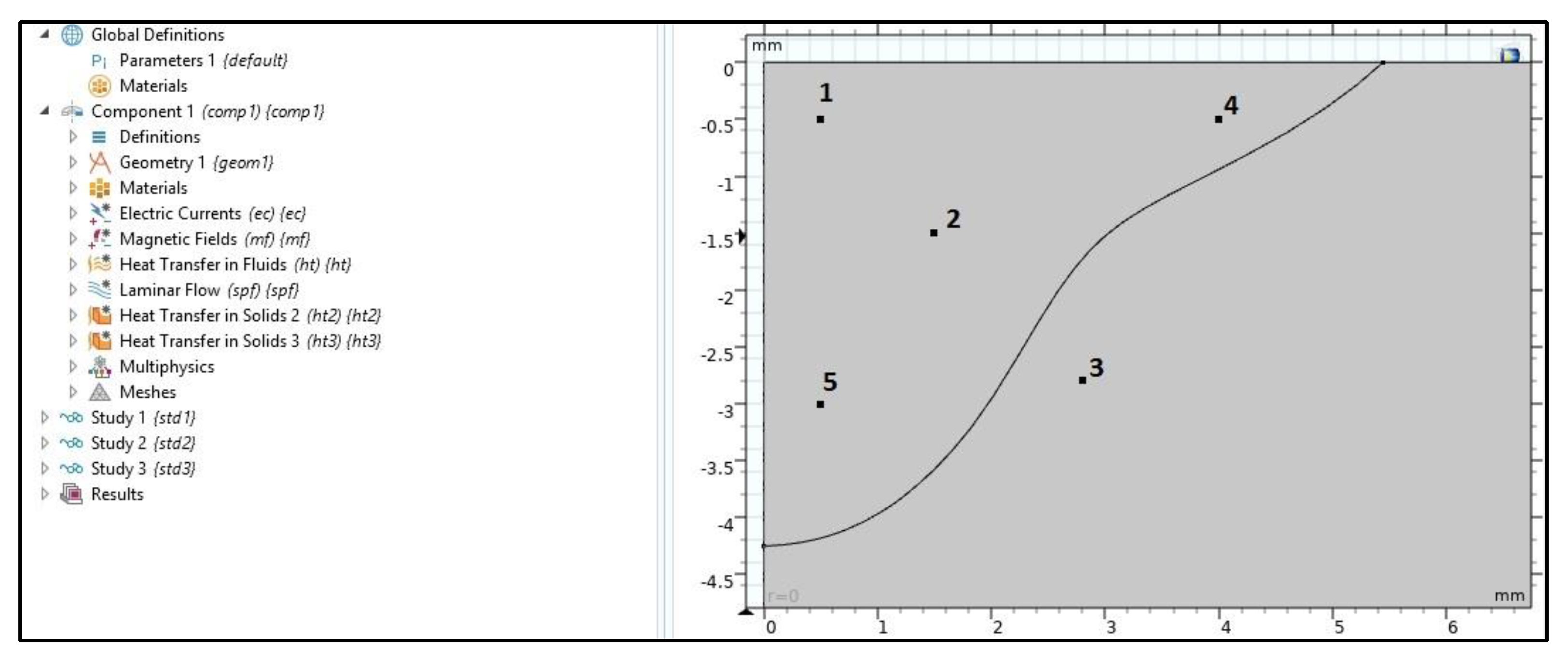

4. Implementation in Comsol

5. Results and Discussion

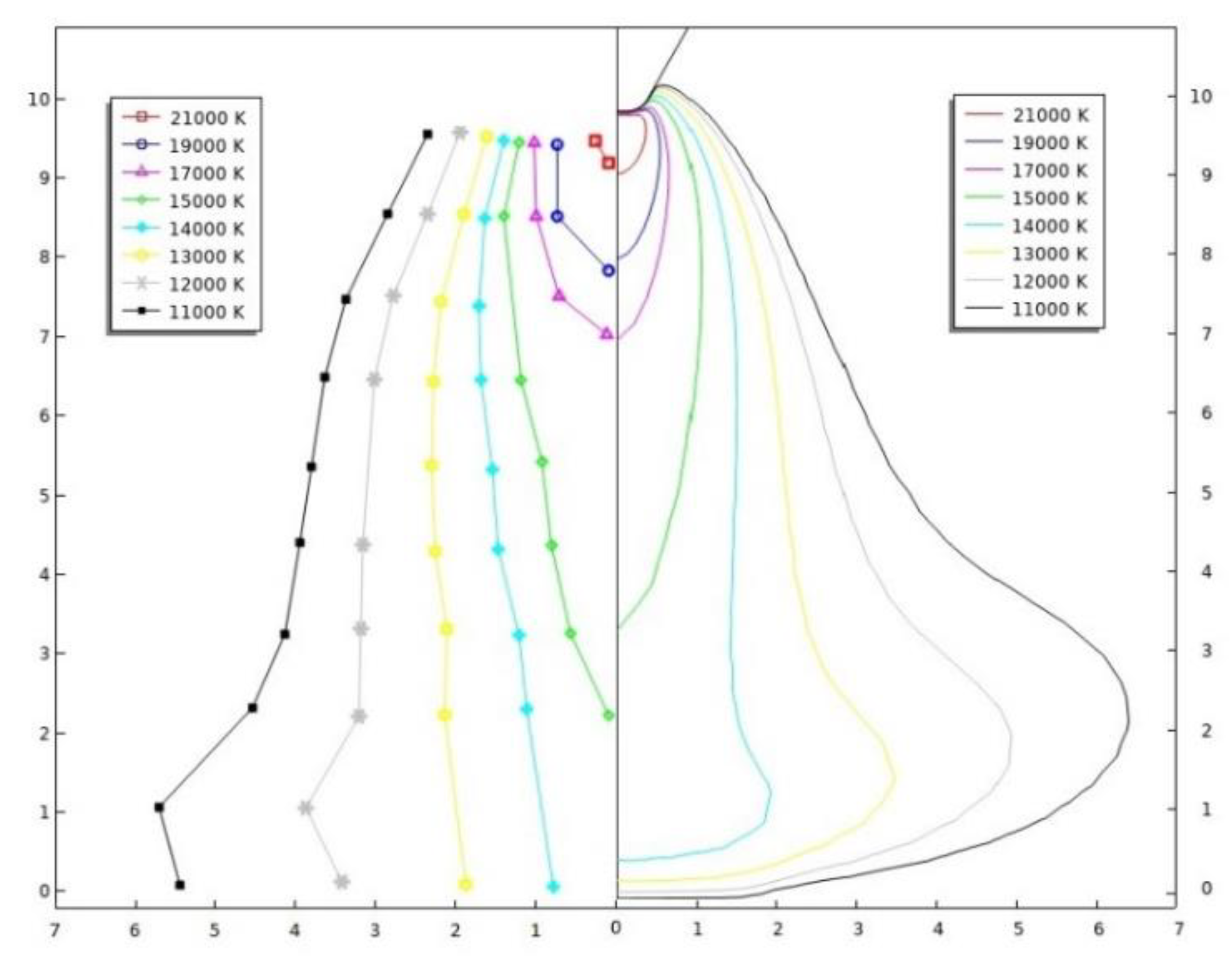

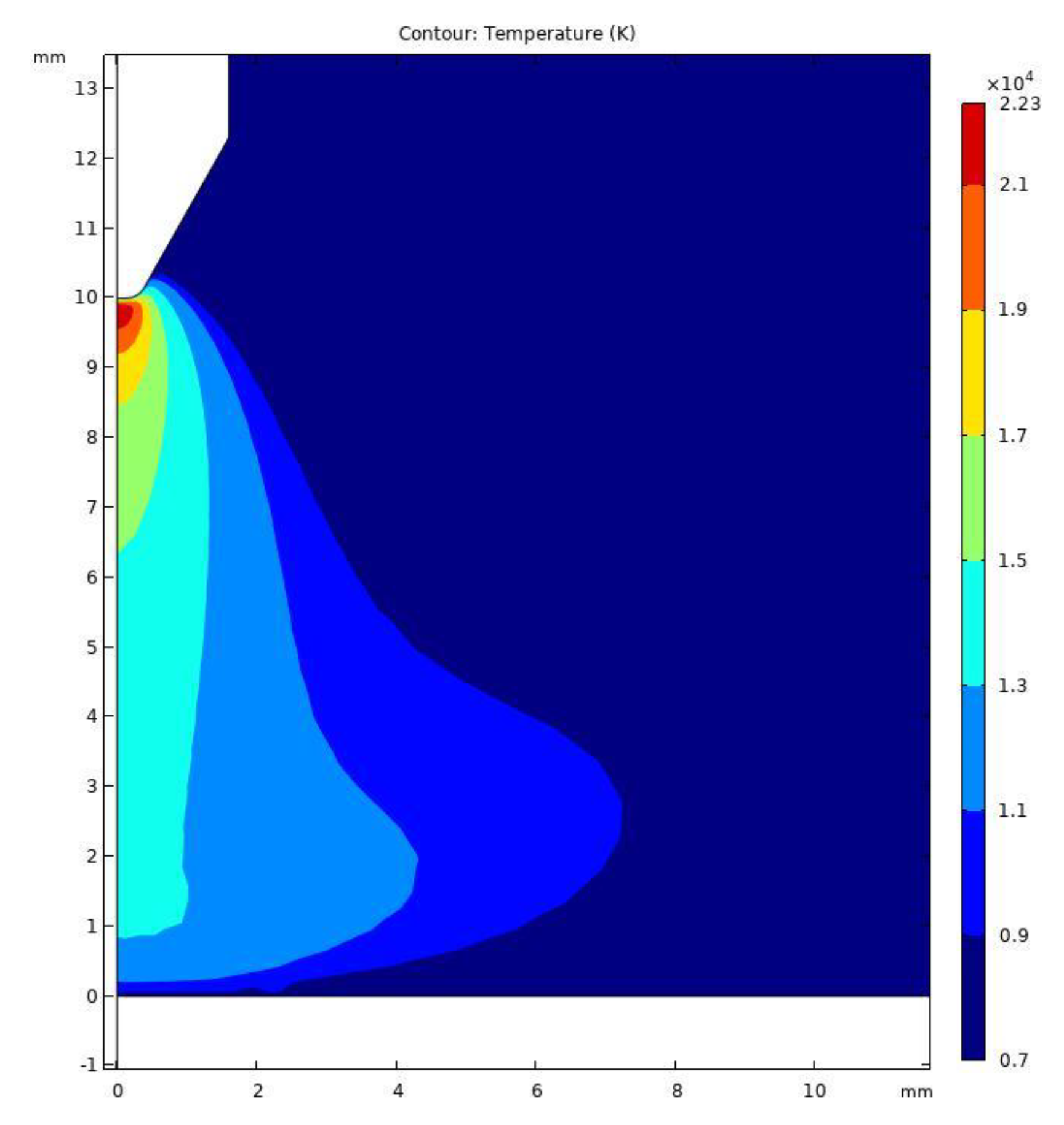

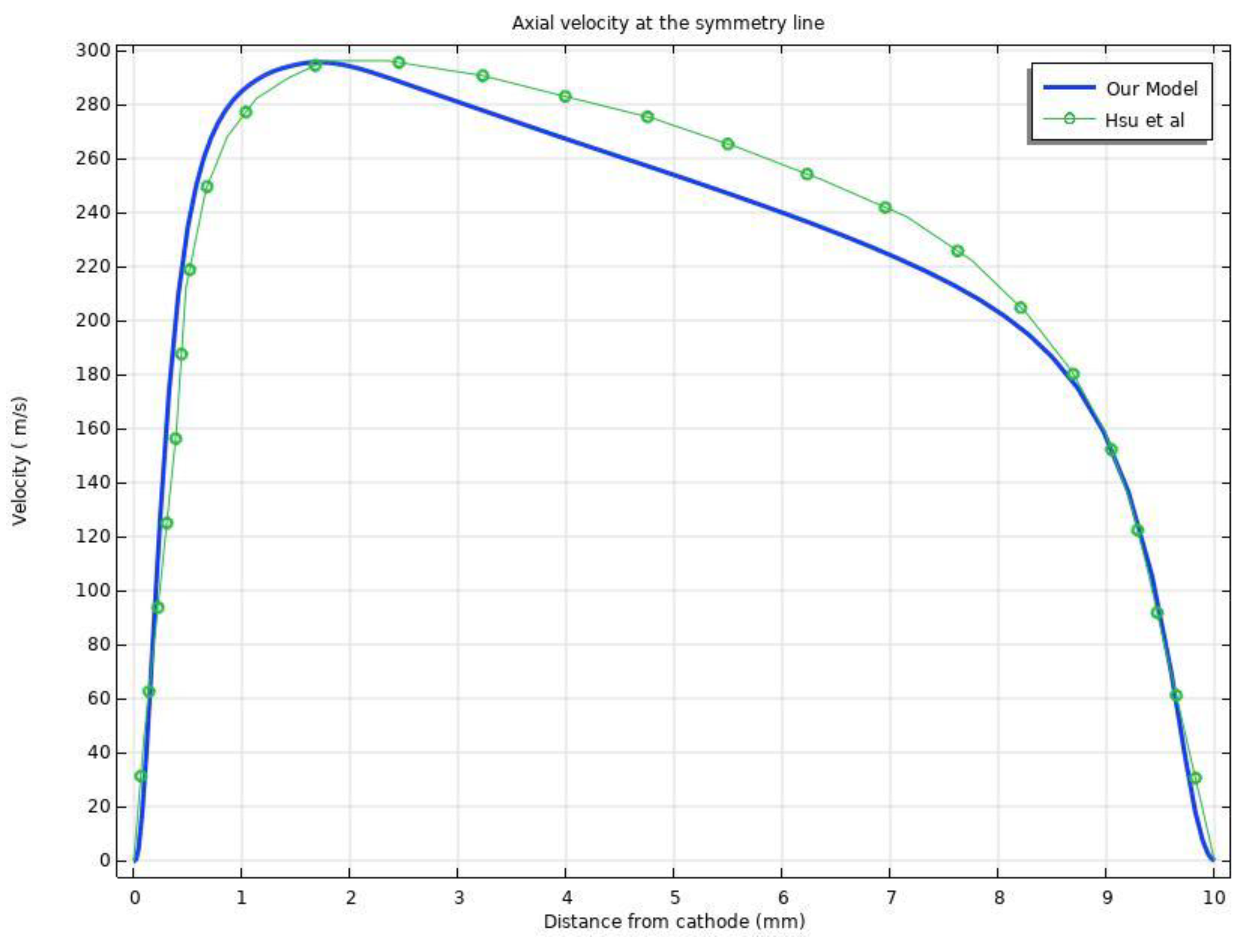

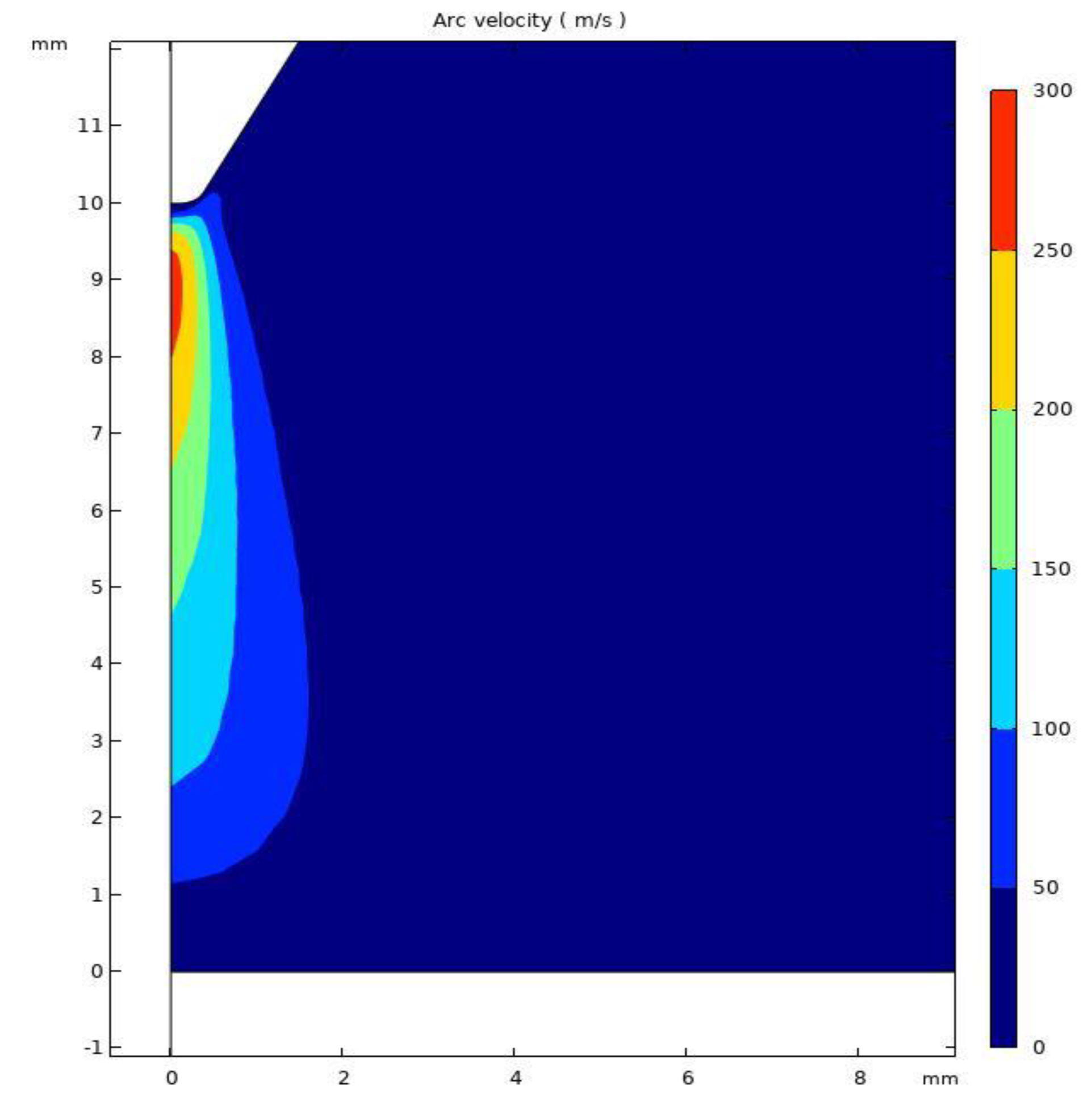

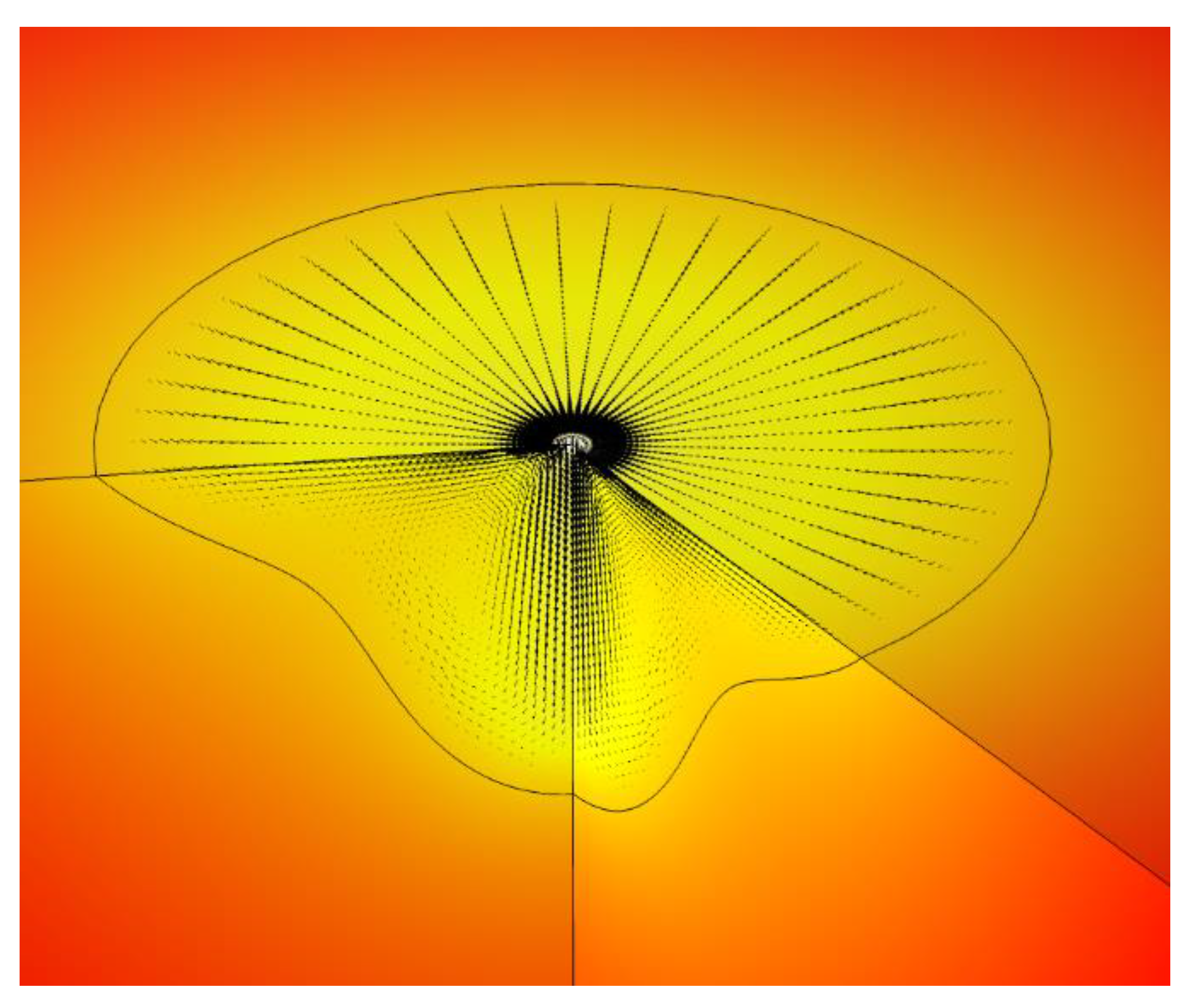

5.1. Plasma Model Results and Validation

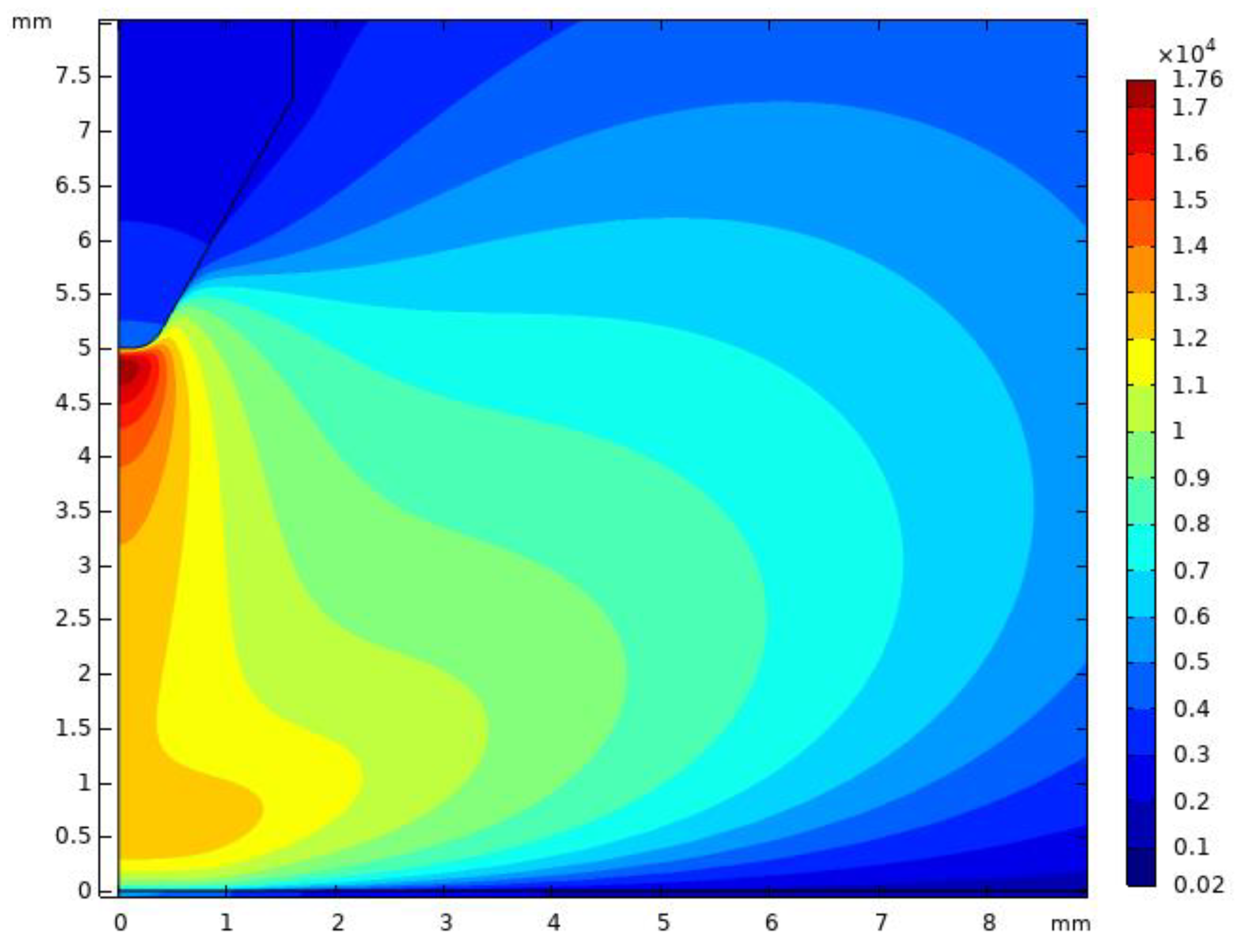

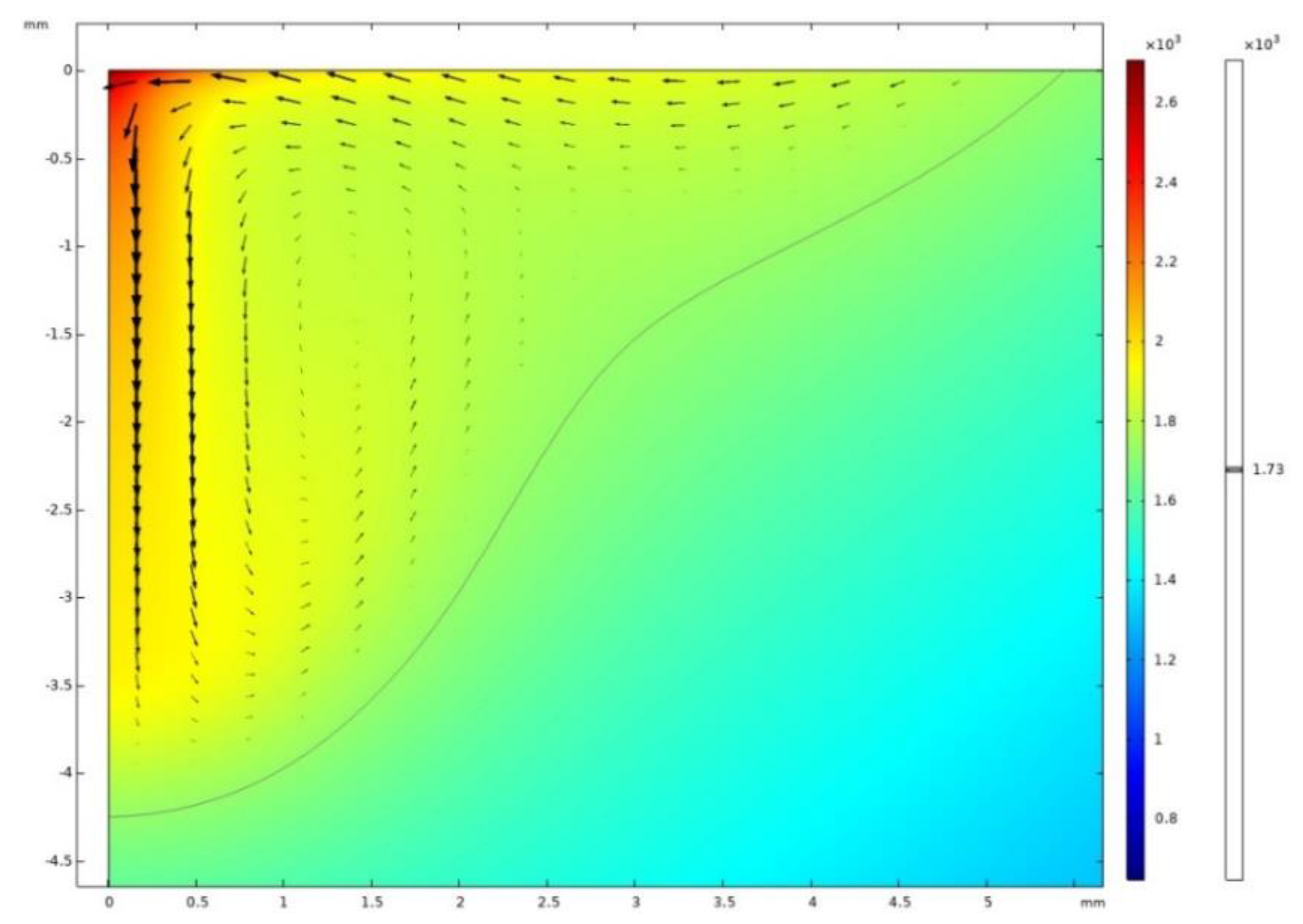

5.2. Weld Pool Results and Validation

5.3. Comparison of Multiphysics, Convensional, and Modified Ellipsoid Models

6. Conclusions

- The temperature distributions obtained show a good approximation between multiphysics and modified application of conventional models with respect to conventional usage of ellipsoidal model.

- Especially in the middle of the pool region, the temperature history significantly changes and approaches to the multiphysics solutions.

- Points inside and near the heat-effected zone in the pool region, both ellipsoidal methods give a similar temperature history until metal melts. After the melting occurs, the modified ellipsoidal method gets closer to the multiphysics solution slowly.

- All implementations of the ellipsoidal method give similar temperature histories for points in the heat-effected zone.

Acknowledgments

References

- Udea, Y.; Yamakawa, T. Analysis of Thermal Elastic-Plastic Stress and Strain During Welding. Trans. Jpn. Weld. Soc. 1971, 2, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, T.T.; Paradis, A.; Masson, J.C. A Simple Method for Evaluating the 3D Welding Effects on the Stiffened Panel Assemblies in Shipbuilding, 3th Int. Conf. on Marine Tech. III 1999, 485–530. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, D. The Theory of Moving Sources of Heat and Its Application to Metal Treatments. Trans ASME, 1946, 68, 849–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelic, V.; Tanbakuchi, R.; Uyehara, O.A; Myers, P.S. Experimental and Computed Temperature Histories in Gas Tungsten Arc Welding of Thin Plates, Weld J. Res Suppl. 1969, 48, 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Goldak, J. ; Chakravarti, A; Bibby M. A New Finite Element Model for Welding Heat Sources. Metallurgical Transactions B 1984, 15, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollár, D. Numerical Modelling on the Influence of Repair Welding During Manufacturing on Residual Stresses and Distortions of T-Joints. Results in Eng. 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, O.; Anthony, J.L; Olabi, A.G. Influence of Girth Welding Material on Thermal and Residual Stress Fields in Welded Lined Pipes. International Journal of Pressure Vessels and Piping 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nart, E.; Celik, Y. A Practical Approach for Simulating Submerged Arc Welding Process Using FE Method. Journal of Const. Steel Research 2013, 84, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Ushio, M.; Tanaka, M. Analysis of the TIG Welding Arc Behavior. Computational Materials Science 1997, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.C.; Etemadi, K.; Pfender, E. Study of the Free-Burning High-Intensity Argon Arc. Journal of Applied Physics 1983, 54, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Lowke, J.J. An Introduction to Physical Phenomena in Arc Welding Processes. Welding International 2004, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Lowke, J.J. Predictions of weld pool profiles using plasma physics. Journal of Physics D-Applied Physics 2007, 40, R1–R23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredia, A. Multiphysics Modeling and Numerical Simulation of GTA Weld Pools, Ph.D. Dissertation in Ecole Polytechnique 2011, France. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L. S. ; C., Wang, L.; Chuansong, W. An Easy-To-Use Multi-Physical Model to Predict Weld Pool Geometry in Keyhole Plasma Arc Welding. Results in Engineering 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Debroy, T.; McNallan, M.T. , Surface Tension of Binary Metal Surface Active Solute Systems Under Conditions Relevant to Welding Metallurgy. Metallurgical Transactions B 1988, 19B, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushio, M. and Wu, C.S. Mathematical Modeling of Three-Dimensional Heat and Fluid Flow in a Moving Gas Metal Arc Weld Pool. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B-Process Metallurgy and Materials Processing Science 1997, 28, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowke, J.J. A Unified Theory of Arcs and their Electrodes. Le Journal de Physique IV, France 1997, 7, C4-283–C4-294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COMSOL Plasma Module User’s Guide, pp. 324, www.comsol.com.

- Mishra, S. , Lienert, T. J., Johnson, M.Q. and Debroy, T. An Experimental and Theoretical Study of Gas Tungsten Arc Welding of Stainless Steel Plates with Different Sulfur Concentrations. Acta Materialia 2008, 56, 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, D. , Voller, V.R. and Reid, K.J. Enthalpy-Porosity Technique for Modeling Convection-Diffusion Phase Change : Application to the Melting of Pure metal. Numerical Heat Transfer 1988, 13, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. , Terasaki, H., Ushio, M. and Lowke, J.J. Numerical Study of a Free-Burning Argon Arc with Anode Melting, Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 2003, 23. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Lowke.. Simple theory of free-burning arcs. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics 1979, 12, 1873. [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Property | Value/Unite |

|---|---|---|

| Constant in surface tension gradient | 4.3 e-4 N m-1 K-1 | |

| Surface tension of pure metal at the melting point | 1.943 N m-1 | |

| Melting temperature of anode metal | 1723 K | |

| Gas constant | 8314.3 J kg-1 mol-1 K-1 | |

| Surface access at saturation | 1.3e-8 kg mol m-2 | |

| Constant related to the entropy of segregation | 3.18e-3 | |

| Standard heat of adsorption | -1.662e8 J kg-1 mol-1 | |

| Activity of the surface active species ( wt pct sulfur) | 0.022 |

| Symbol | Description | Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| z,r | The axial, radial coordinate | m |

| vr,vz | Radial and axial velocity | m s-1 |

| t | Time | s |

| ρ | Density | kg m-3 |

| p | Pressure | N m-2 |

| pCF | Arc pressure of the anode surface | N m-2 |

| μ | Viscosity | kg m-1 s-1 |

| FVr,FVz | Axial and radial volumetric forces | N m-3 |

| ρ0 | Gas density in the arc plasma domain | kg m-3 |

| jr,jz | Axial, radial current density | A m-2 |

| jCF | Current density of the anode surface | A m-2 |

| j0 | Welding current density | A m-2 |

| g | Acceleration of gravity | m s-2 |

| Bθ | Azimuthal magnetic flux density | Wb m-2 |

| Ar,Az | Radial and axial Magnetic vector potential | Wb m-2 |

| μ0 | Magnetic permeability of vacuum | H m-1 |

| φ | Potential | V |

| σ | Electric conductivity | S m-1 |

| T | Temperature | K |

| cp | Heat capacity | J kg-1 K-1 |

| k | Thermal conductivity | W m-1 K-1 |

| Sv | Volumetric heat source | W m-3 |

| q | Heat flux density | W m-2 |

| qCF | Heat flux density of the anode surface | W m-2 |

| E | Electric field | V m-1 |

| kB | Boltzmann's constant | J K-1 |

| Qrad | Radiation loss | W m-3 |

| e | Electronic charge | C |

| FElectrode | Additional energy flux of the cathode | W m-2 |

| FAnode | Additional energy flux of the anode | W m-2 |

| ε | The emissivity of the surface | |

| α | Stefan-Boltzmann constant | W m-2 K-4 |

| ϕK | The work function of the cathode | V |

| ϕA | The work function of the anode | V |

| ϕeff | The effective work function of the cathode | V |

| je | Electron current density | A m-2 |

| ji | Ion current density | A m-2 |

| jR | Richardson-Dushman current density | A m-2 |

| Vi | The ionization potential of the plasma | V |

| AR | Richarson’s constant | A m-2K-2 |

| β | Thermal expansion coefficient of molten metal | K-1 |

| ρm | Molten metal density in the weld pool | kg m-3 |

| dγ/dT | Surface tension gradient | N m-1 K-1 |

| γ | Surface tension coefficient | N m-1 |

| Aγ | Constant in surface tension gradient | N m-1 K-1 |

| Surface tension of pure metal at the melting point | N m-1 | |

| Tm | Melting temperature of anode metal | K |

| Rg | Gas constant | J kg-1 mol-1 K-1 |

| Γs | Surface access at saturation | kg mol m-2 |

| k1 | Constant related to entropy of segregation | |

| ΔH0 | Standard heat of adsorption | J kg-1 mol-1 |

| ai | Activity of the surface active species ( wt pct sulfur) | |

| K | Equilibrium constant for segregation | |

| cpeq | Equivalent specific heat for phase change | J kg-1 K-1 |

| Lf | Latent heat for fusion | J kg-1 K-1 |

| fL | Liquid fraction | |

| Ts,TL | Solidus and liquidus temperature of metal | K |

| μL | The viscosity of liquid metal | kg m-1 s-1 |

| μS | Viscosity of solid metal | kg m-1 s-1 |

| Model Type | Ssss Sub-Dicipline |

Boundary Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma Physics Model | Electric Currents |

AD : Axial Symmetry ( = 0), DE : Graund (φ = 0), EF,FG,GI : Electric Insulation (n.J = 0), AI :Normal Current Density (−n.J = J0) |

| Magnetic Fields |

AD : Axial Symmetry B = 0, AG,GE,ED : Magnetic Insulation (n x A = 0) | |

| Heat Transfer |

AD : Axial Symmetry ( = 0), DE,EF : Convective Heat Flux (q0 = h.(Text – T)) AG,GF : Temperature (T = 300 K), BKJI : Boundary Heat Source (Eq.11) CF : Boundary Heat Source (Eq.15) |

|

| Fluid Flow |

AC : Axial Symmetry ( = 0, vr = 0), CF, BKJI : Wall (vr = 0, vz = 0) IH: inlet (vz = −Uargon), HG,GF : Open Boundary |

|

|

MHD ( Magneto-Hydrodynamics) Model |

Electric Currents |

DC : Axial Symmetry ( = 0), DE : Graund (φ = 0) , EF: Electric Insulation (n.J = 0) CF : Normal Current Density obtained from the study 1 (−n.J = JCF) |

| Magnetic Fields |

CD : Axial Symmetry (B = 0), DE,EF,FC : Magnetic Insulation (n x A = 0) | |

| Heat Transfer |

DC : Axial Symmetry ( = 0), DE,EF : Convective Heat Flux (q0 = h.(Text – T)) CF : Boundary Heat Source obtained from the study 1 (−n.q = qCF) |

|

| Fluid Flow |

DC : Axial Symmetry ( = 0, vr = 0), DE,EF : Wall (vr = 0, vz = 0) CF : Boundary stress obtained from the study 1 arc pressure (−n.p = pCF) |

|

| Ellipsoid Heat Source Model | Heat Transfer |

DC : Axial Symmetry ( = 0), DE,EF : Convective Heat Flux (q0 = h.(Text – T)) CF : Radiation loss Note: Ellipsoid Volumetric Heat Source was applied to the welding pool geometry |

| Property | Value/Unite |

|---|---|

| Coefficient of thermal expansion | 4.5e-6 K-1 |

| Density | 19350 kg m-3 |

| Heat capacity | 132 J kg-1 K-1 |

| Thermal conductivity | 175 W m-1 K-1 |

| Electrical conductivity | 20e6 S/m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).