Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Saguaro Phenology

1.2. North American Monsoon

1.3. Defining Monsoon Onset

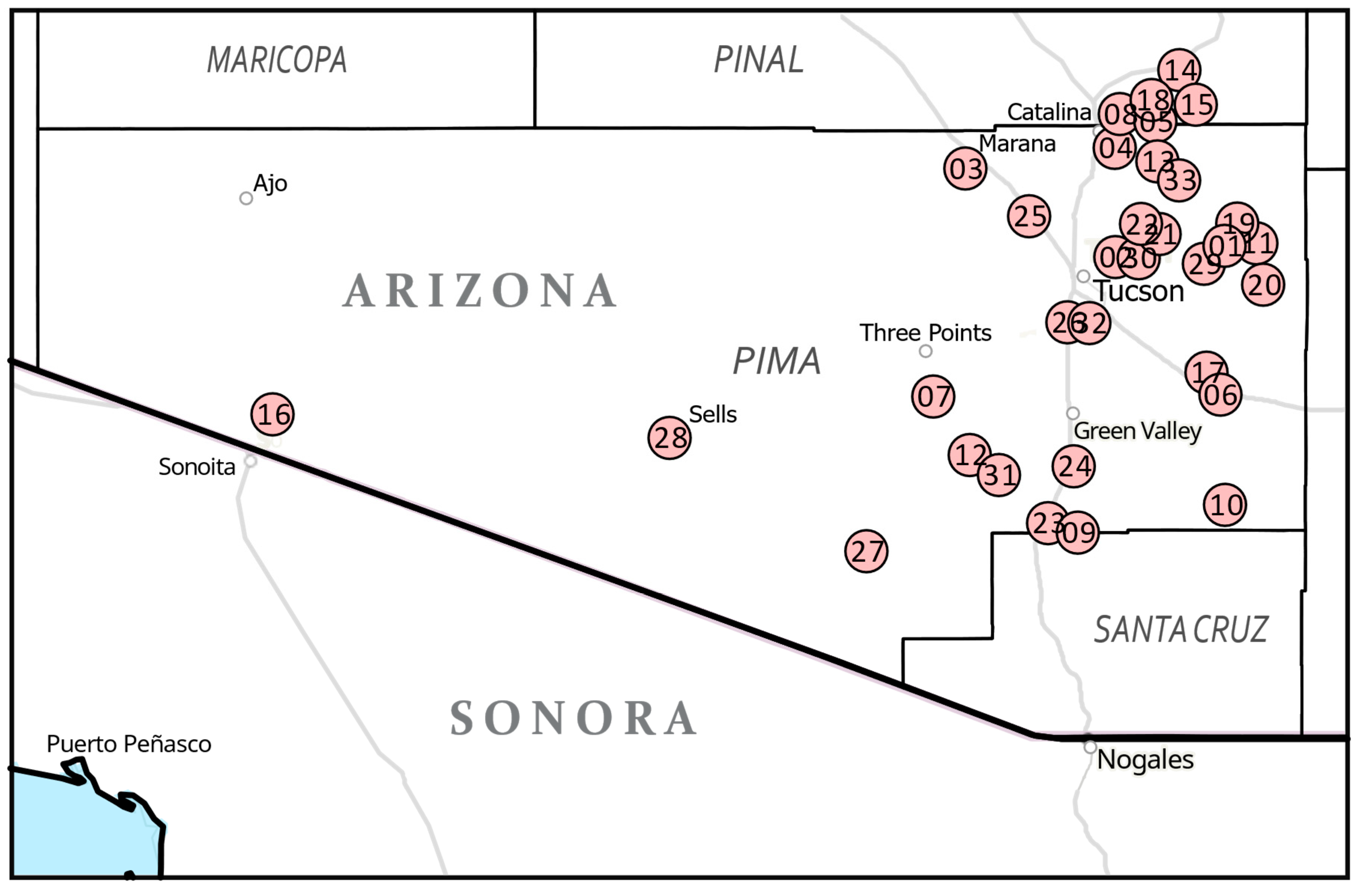

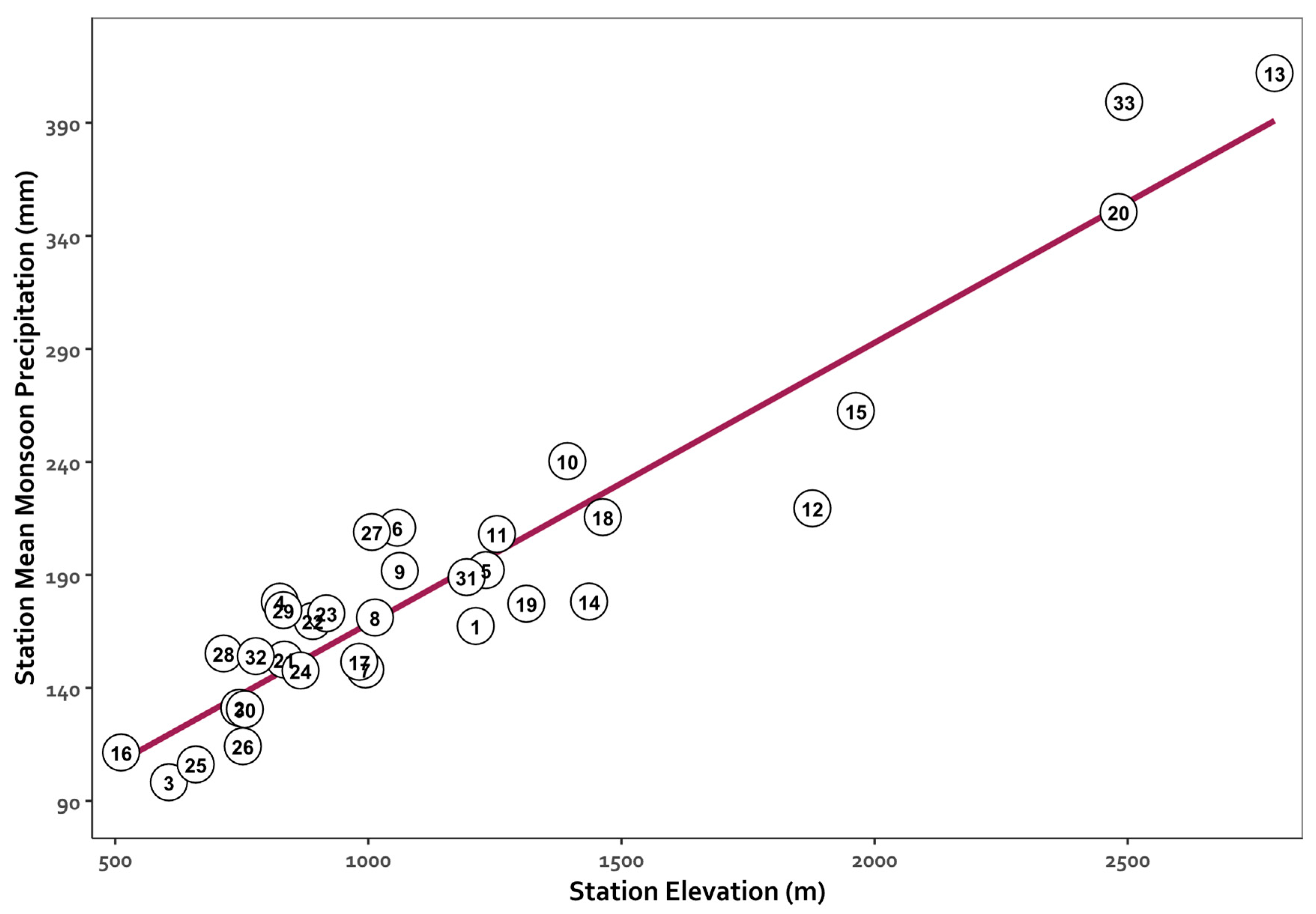

2. Methods

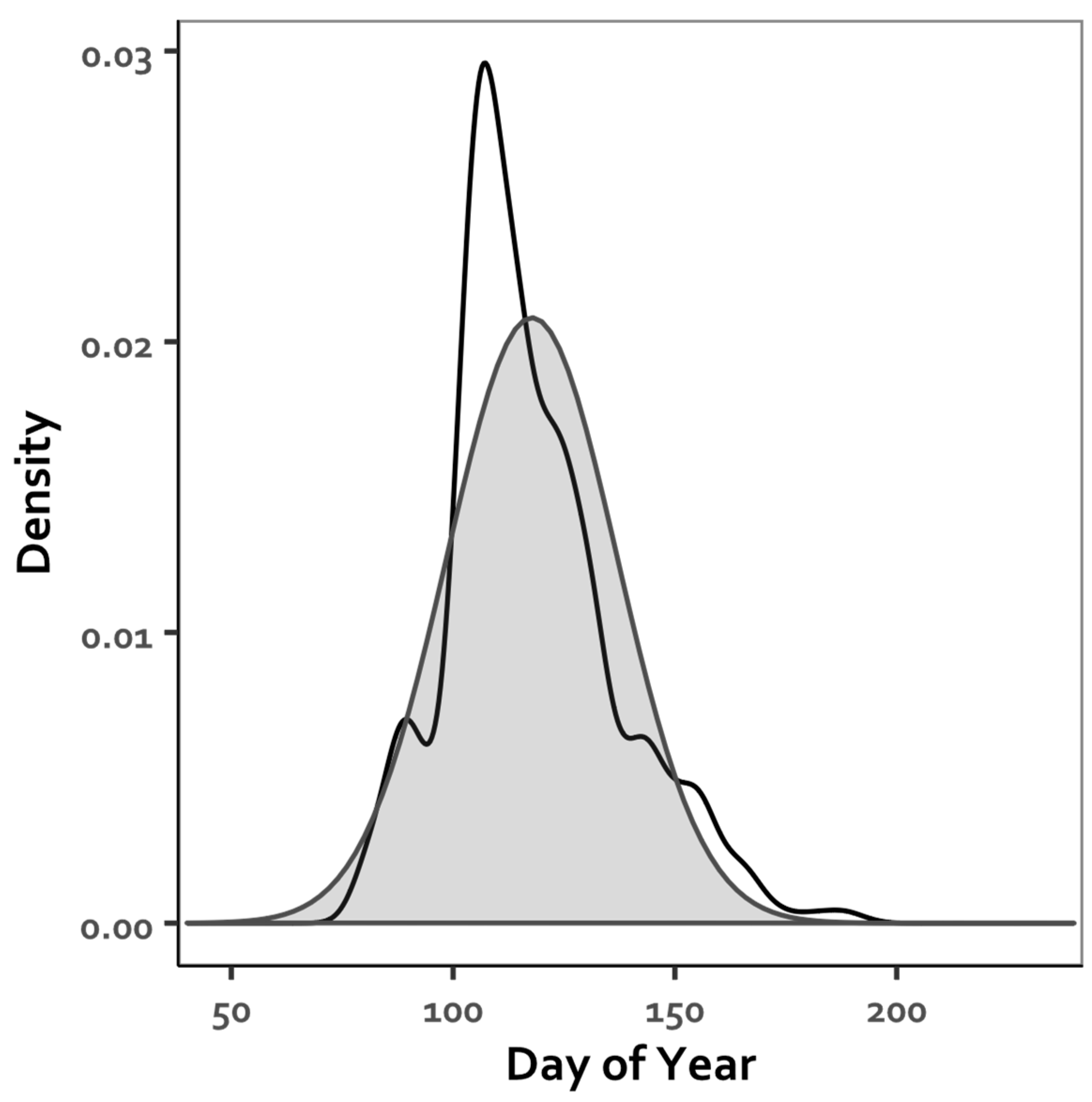

- Day-of-year (DOY onset) of the first one-day rainfall events of ≥10 mm from 1 June -30 Sept., 1990-2022. To mitigate possible calendar bias in our method of determining the day-of year of monsoon onset the dates of monsoon onset were counted from the date of the vernal equinox of that year instead of from the first of the year. The date of the vernal equinoxes was obtained from the seasons calculator at timeanddate.com for Tucson, Arizona [35].

- Total monsoon rainfall (MR, mm, 1 June- 30 Sept.).

- Total annual rainfall (AR, mm).

- Proportion of mean annual station rainfall falling from 1 June – 30 Sept (PAR). Each year value in this vector is calculated as the difference between monsoon rainfall of the year and station mean annual rainfall across years.

3. Results & Discussion

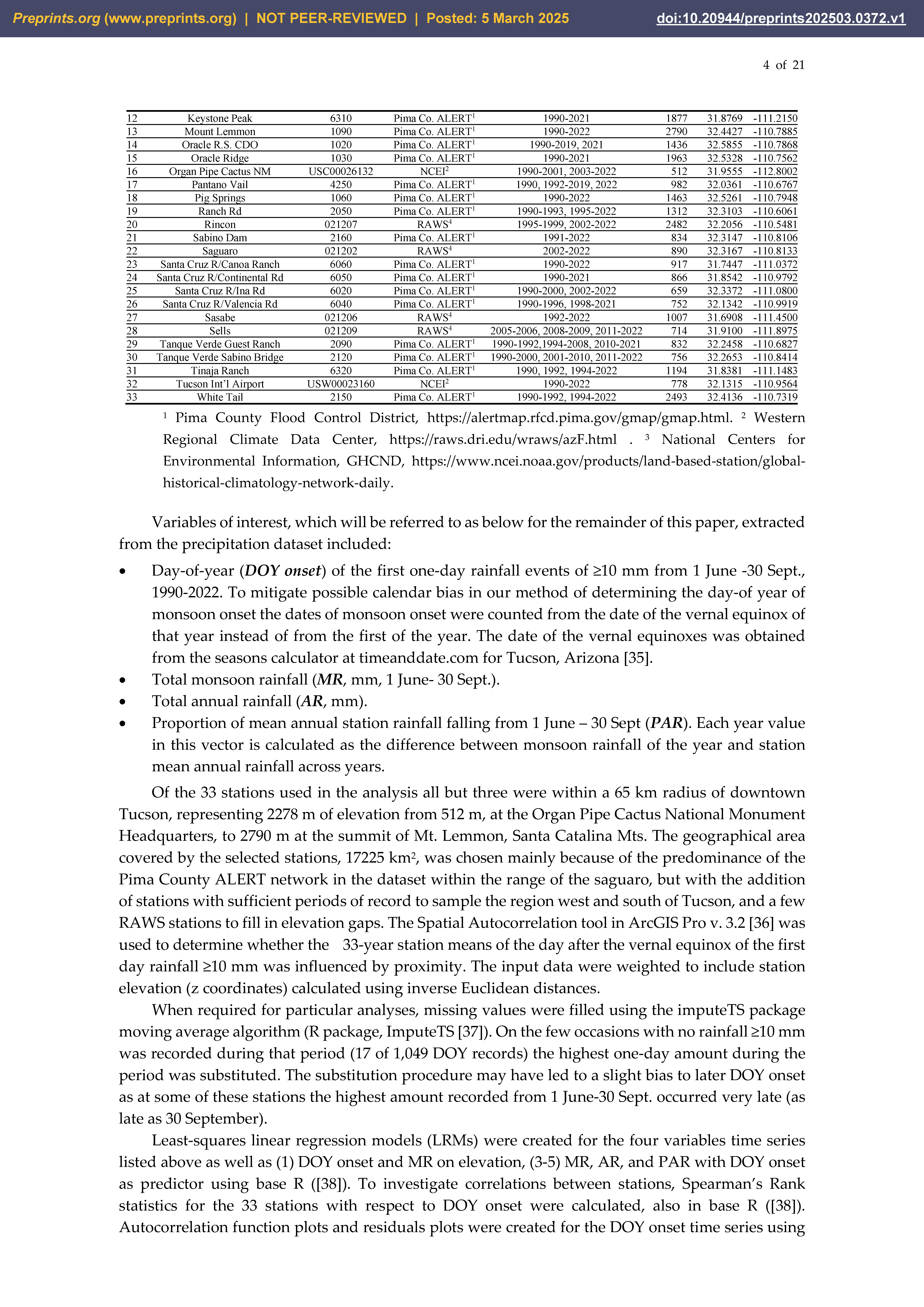

3.1. Effect of Elevation on DOY Onset & Precipitation

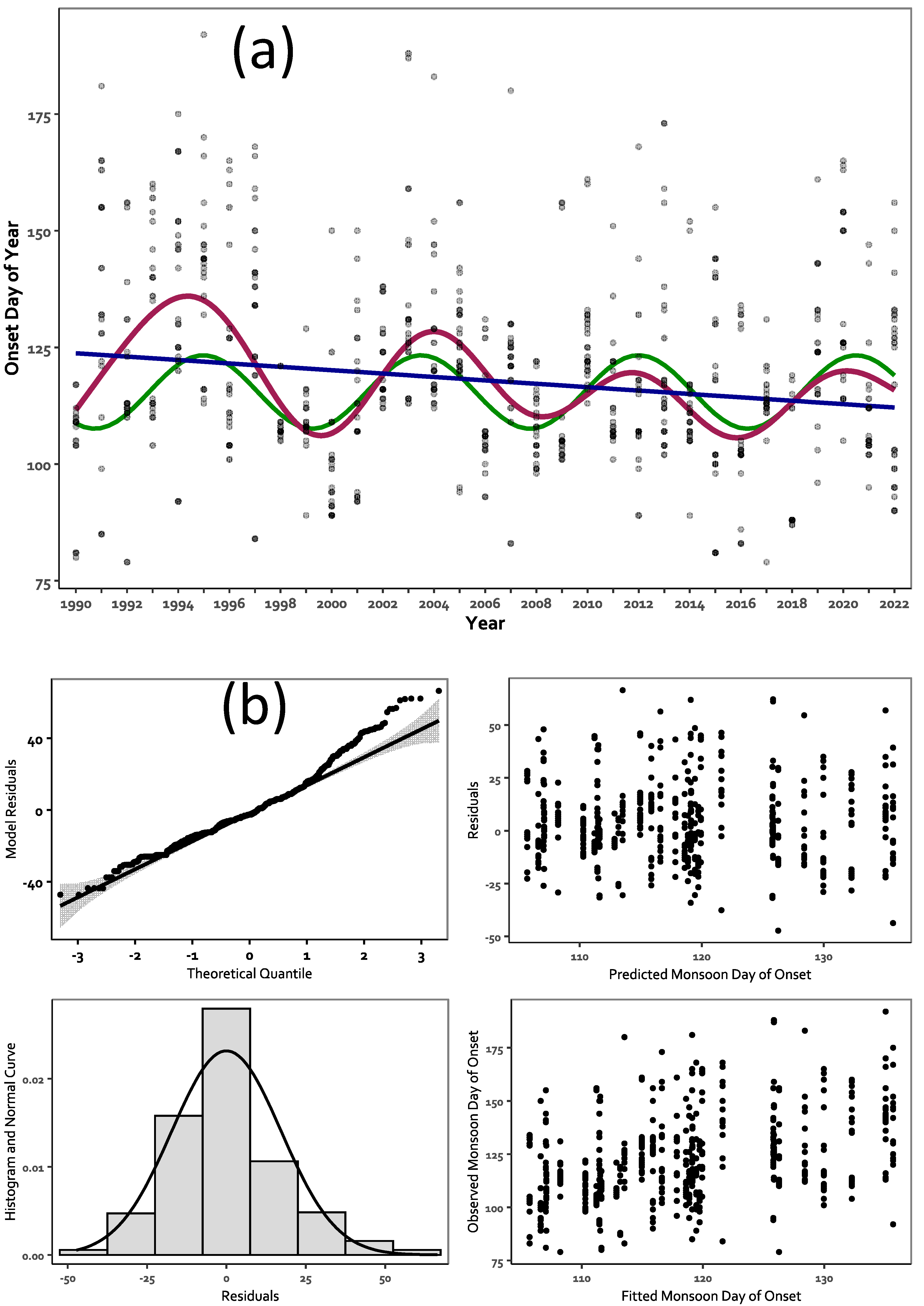

3.2. Monsoon Day-of-Year Onset

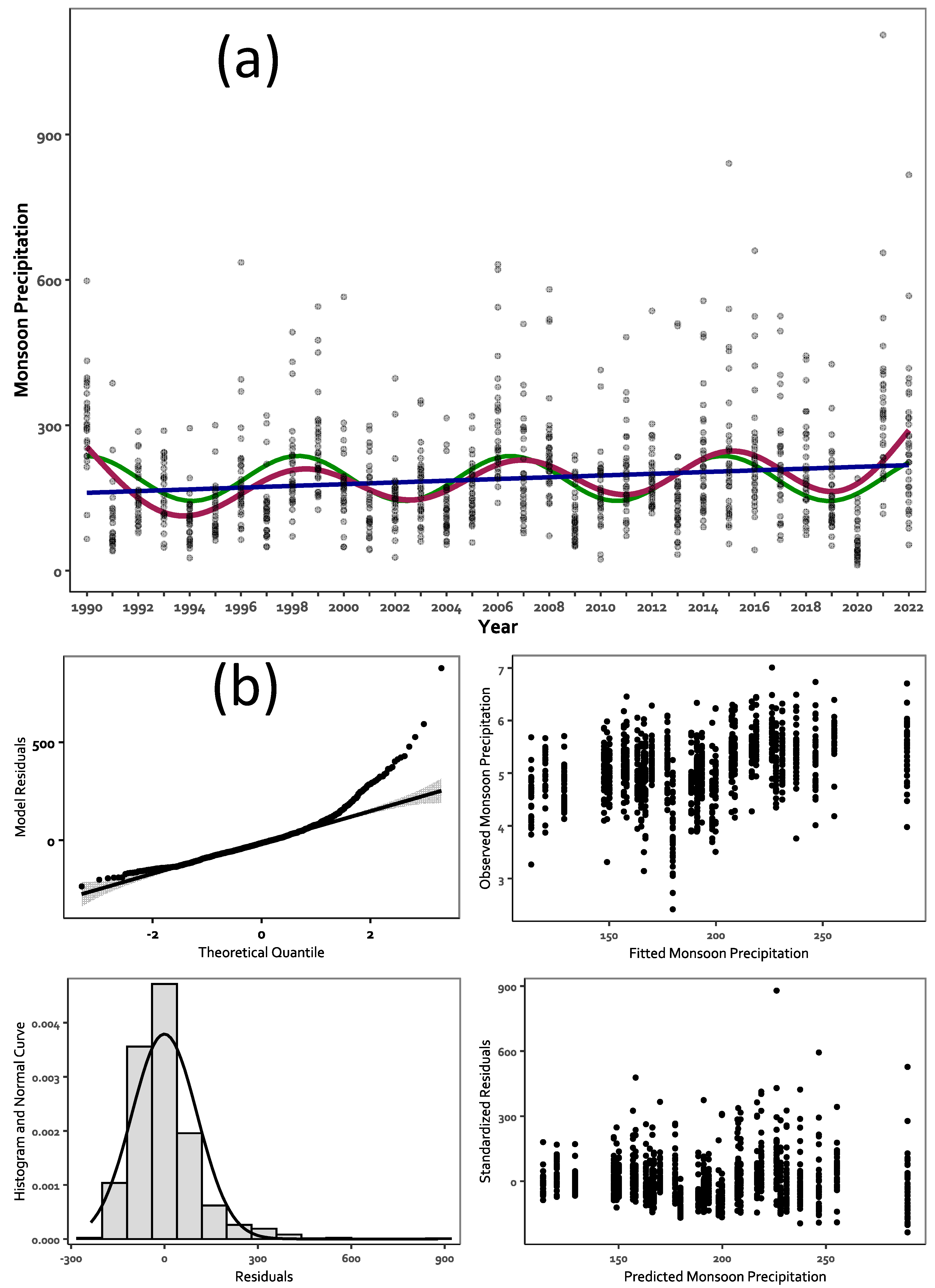

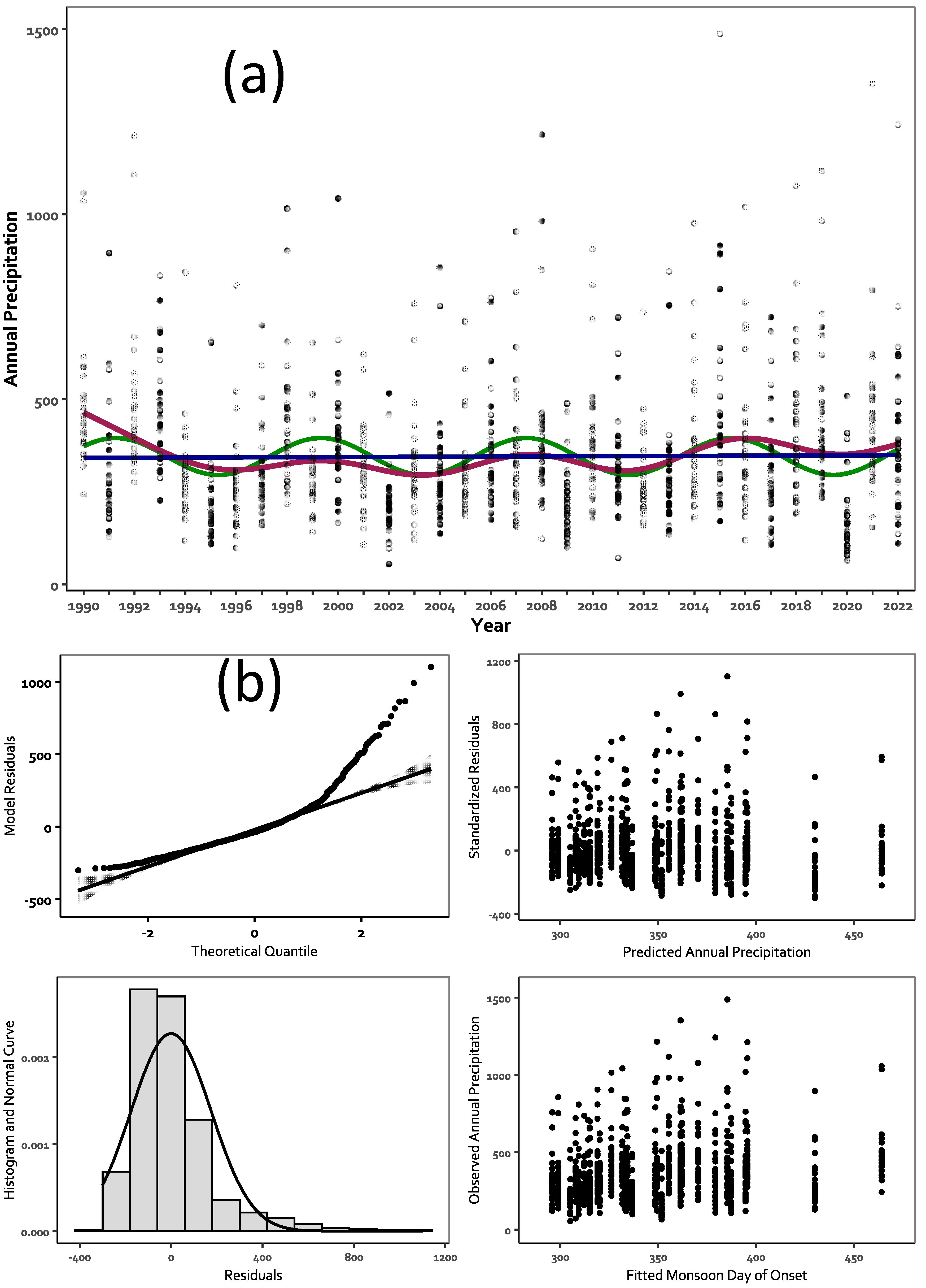

3.3. GAMs, LRMs, and SRMs

3.4. Previous Research

3.5. Saguaro Phenology

| Reference | Aim of study | Onset identifier(s) | Geography | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | Huntington [55] | Describe monsoon climate of Ariz., New Mex. | Change in wind direction from westerly to southerly. | Ariz., New Mex. |

| 1955 | Bryson and Lowry [68] | Map shift in dominant air masses signaling monsoon season. | Sharp changes in Raininess Index. | Ariz. |

| 1973 | Brenner [27] | Describe antecedent monsoon climate of Ariz., investigate possible GoC connection. | Changes in several surface observations. | Ariz. |

| 1993 | Douglas, et al. [58] | Describe synoptic climatology Mex., U.S. monsoon, identify moisture source(s). | Rainfall amounts and wind shifts. | Mex., SW U.S. |

| 1997 | Higgins, et al. [59] | Diagnose atmospheric conditions preceding monsoon onset. | Precip. index magnitude & duration, ⫹0.5 mm day⫺1 for 3 days. | Ariz., western New Mex. |

| 1998 | Higgins, et al. [60] | Extend earlier work, diagnose variability of Mex.-U.S. summer precip. | Precip. index magnitude & duration, ⫹0.5 mm day⫺1 for 3 days. | Ariz., western New Mex. |

| 1999 | Higgins, et al. [61] | Extend earlier work, identify factors influencing variability. | Varies by region; precip. index magnitude & duration, ⫹0.5-2 mm day⫺1 for 3-5 days. | Ariz., western New Mex., SW Mex. |

| 2002 | Mitchell, et al. [62] | Onset & evolution of monsoon rainfall related to GOC SSTs. | Varies by region; precip. index magnitude & duration, ⫹0.5-2 mm day⫺1 for 3-5 days.. | GoC, Ariz., New Mex. |

| 2004 | Ellis, et al. [56] | Develop regional criteria for monsoon onset. | Mean daily dew-point threshold 12.2º or 12.8º for 3 days. | SW U.S. |

| 2007 | Grantz, et al. [69] | NAM timing, rainfall amount, large-scale trends drivers. | Percentile of monsoon precip. threshold. | Ariz., New Mex. |

| 2008 | Liebmann, et al. [53] | Monsoon onset dates Mex. & U.S. climatology variability, season length, rate, SST topography influences. | Anomalous rainfall accumulation. | Mex., SW U.S. |

| 2009 | Turrent and Cavazos [63] | Clarify monsoon forcing with land-sea thermal flux and influence on onset. | First 5-day period mean core region precip. >1 mm. | NW Mex. |

| 2011 | Crimmins, et al. [70] | Relate summer flowering onset to monsoon climatological events. | 3-day mean daily dewpoint threshold at TUS. | Finger Rock Canyon, Pima Co., Ariz. |

| 2012 | Arias, et al. [64] | Determine multidecadal variations in monsoon seasonality & strength. | Pentad after which the rain rate > than annual mean rain rate in 6 of 8 preceding pentads and after which rain rate > than annual mean in 6 of 8 pentads. | NW Mex. |

| 2015 | Arias, et al. [25] | Investigate climate dynamics influencing variability of NAM and SAM. | Pentad after which the rain rate > than annual mean rain rate in 6 of 8 preceding pentads and after which rain rate > than annual mean in 6 of 8 pentads. | North America, South America |

| 2017 | Meyer and Jin [54] | Correct regional and global models for projected future climate effects on monsoon dynamics. | First occurrence after 1 May with three consecutive days with at least 0.5 mm day−1. | SW U.S., Mex. |

| 2021 | García-Franco, et al. [57] | Introduce new onset identifier. | Wavelet transform (maximum sum of wavelet coefficients) on precip. time series. | Mex., India |

| 2021 | Fonseca-Hernandez, et al. [65] | Analyze mixing mechanisms responsible for temporal and spatial variations of GoC boundary layer during NAM onset. | First day first sequence of five consecutive days mean precip. rate =/> 2 mm/day. | NW Mex. |

| 2021 | Ashfaq, et al. [26] | Construct regional climate model of monsoon change with increased greenhouse gas forcing. | Pentad after minimum seasonality of precip. value, similar to Bombardi and Carvalho [74]. | Global monsoon domains |

| 2024 | Duan, et al. [67] | Identify and analyze NAM extreme events. | First 1 mm/day for 5 days after 1 June. | GoC and surrounding lands |

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest declaration

Funding

References

- Conn, J.; Snyder-Conn, E. The relationship of the rock outcrop microhabitat to germination, water relations, and phenology of Erythrina flabelliformis (Fabaceae) in southern Arizona. Southwestern Naturalist 1981, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J. E.; Dimmitt, M. A. Flowering phenology of six woody plants in the northern Sonoran Desert. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 1994, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, E.; Búrquez, A. Effects of Plant Size and Weather on the Flowering Phenology of the Organ Pipe Cactus (Stenocereus thurberi). Annals of Botany 2008, 102, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisogni, A.; De Manincor, N.; Bertelsen, C. D.; Rafferty, N. E. Long-term changes in flowering synchrony reflect climatic changes across an elevational gradient. Ecography 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J. E.; Turner, R. M. The influence of climatic variability on local population dynamics of Cercidium microphyllum (foothill paloverde). Oecologia 2002, 130, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachmann, L. J.; Wiens, J. F.; Franklin, K.; Crausbay, S. D.; Landau, V. A.; Munson, S. M. Dominant Sonoran Desert Plant Species Have Divergent Phenological Responses to Climate Change. Madroño, 2021; 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, J. J.; Peachey, W. D.; Gerst, K. L. A decade of flowering phenology of the keystone saguaro cactus (<i>Carnegiea gigantea</i>). American Journal of Botany 2019, 106, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J. E. Environmental determinants of flowering date in the columnar cactus Carnegiea gigantea in the northern Sonoran Desert. Madrono 1996, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, T.; Swann, D.; Sotelo, G.; Perkins, N. Is the timing of saguaro flowering changing? Using citizen science to understand changes in saguaro phenology. Western National Parks Association, Tucson, Arizona: 2021; p 12.

- Steenbergh, W. F.; Lowe, C. H. Ecology of the Saguaro: II, Reproduction, Germination, Establishment, Growth, and Survival of the Young Plant: Warren F. Steenbergh & Charles H. Lowe; Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1977.

- Bowers, J. E. Regeneration of triangle-leaf bursage (Ambrosia deltoidea: Asteraceae): germination behavior and persistent seed bank. The Southwestern Naturalist 2002, 47, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J. E. New evidence for persistent or transient seed banks in three Sonoran Desert cacti. The Southwestern Naturalist 2005, 50, 482–487. [Google Scholar]

- Stella, J. C.; Battles, J. J.; Orr, B. K.; Mcbride, J. R. Synchrony of Seed Dispersal, Hydrology and Local Climate in a Semi-arid River Reach in California. Ecosystems 2006, 9, 1200–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, T. M.; Bertelsen, C. D.; Crimmins, M. A. Within-season flowering interruptions are common in the water-limited Sky Islands. International Journal of Biometeorology 2014, 58, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S. E.; Pendleton, B. K. Evolutionary drivers of mast-seeding in a long-lived desert shrub. American Journal of Botany 2015, 102, 1666–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevéy, J. S.; Vitasse, Y.; Fu, Y. Editorial: Experimental Manipulations to Predict Future Plant Phenology. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, C.; Higgins, W.; Amador, J.; Ambrizzi, T.; Garreaud, R.; Gochis, D.; Gutzler, D.; Lettenmaier, D.; Marengo, J.; Mechoso, C. R.; et al. Toward a Unified View of the American Monsoon Systems. Journal of Climate 2006, 19, 4977–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, S. The monsoon system: Land–sea breeze or the ITCZ? Journal of Earth System Science 2018, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M.; Voigt, A.; Boos, W. R.; Braconnot, P.; Hargreaves, J. C.; Harrison, S. P.; Kang, S. M.; Mapes, B. E.; Scheff, J.; Schumacher, C.; et al. Global energetics and local physics as drivers of past, present and future monsoons. Nature Geoscience 2018, 11, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geen, R.; Bordoni, S.; Battisti, D. S.; Hui, K. Monsoons, ITCZs, and the Concept of the Global Monsoon. Reviews of Geophysics 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ding, Q. Global monsoon: Dominant mode of annual variation in the tropics. Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans, 2008; 44, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, W.; Gochis, D. Synthesis of Results from the North American Monsoon Experiment (NAME) Process Study. Journal of Climate 2007, 20, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.; Higgins, R. W. Relationships between Sea Surface Temperatures in the Gulf of California and Surge Events. Journal of Climate 2008, 21, 4312–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidema, P.; Fairall, C.; Hartten, L. M.; Hare, J. E.; Wolfe, D. On Air–Sea Interaction at the Mouth of the Gulf of California. Journal of Climate 2007, 20, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, P. A.; Fu, R.; Vera, C.; Rojas, M. A correlated shortening of the North and South American monsoon seasons in the past few decades. Climate Dynamics, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Cavazos, T.; Reboita, M. S.; Torres-Alavez, J. A.; Im, E.-S.; Olusegun, C. F.; Alves, L.; Key, K.; Adeniyi, M. O.; Tall, M. Robust late twenty-first century shift in the regional monsoons in RegCM-CORDEX simulations. Climate Dynamics 2021, 57, 1463–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, I. S. A surge of maritime tropical air--Gulf of California to the southwestern United States; US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration …, 1973.

- Carleton, A. Synoptic and satellite aspects of the southwestern US summer ‘monsoon’. International Journal of Climatology 1985, 5, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombardi, R. J.; Moron, V.; Goodnight, J. S. Detection, variability, and predictability of monsoon onset and withdrawal dates: A review. International Journal of Climatology 2020, 40, 641–667. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J. E.; Turner, R. M.; Burgess, T. L. Temporal and spatial patterns in emergence and early survival of perennial plants in the Sonoran Desert. Plant Ecology (formerly Vegetatio) 2004, 172, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pima County Regional Flood Control District. PCRFCD ALERT Google Data Display Map, 2023.

- Global Historical Climatology Network - Daily (GHCN-Daily), Version 3. NOAA National Climatic Data Center. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/cdo-web/search?datasetid=GHCND (accessed 9/23/2023).

- Menne, M. J.; Durre, I.; Vose, R. S.; Gleason, B. E.; Houston, T. G. An Overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network-Daily Database. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 2012, 29, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAWS USA Climate Archive. Western Regional Climate Center. https://raws.dri.edu/wraws/ (accessed 9/23/2023).

- Thorsen, S. Solstices & Equinoxes for Tucson (1990-2022). 2024. https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/seasons.html?n=393 (accessed 2023 9/23/2023).

- ESRI. Spatial Autocorrelation Tool, ArcGIS Pro 3.2. Environmental Systems Research Institute, 2023. https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/spatial-autocorrelation.htm (accessed 2023 9/23/2023).

- Moritz, S.; Bartz-Beielstein, T. imputeTS: Time Series Missing Value Imputation in R. The R Journal 2017, 9, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 9/23/2023).

- Hyndman, R.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Bergmeir, C.; Caceres, G.; Chhay, L.; O'Hara-Wild, M.; Petropoulos, F.; Razbash, S.; Wang, E.; Yasmeen, F. forecast: Forecasting functions for time series and linear models; 2024. https://pkg.robjhyndman.com/forecast/.

- Pohlert, T. trend: Non-Parametric Trend Tests and Change-Point Detection; 2023. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=trend.

- Wood, S. N. Generalized Additive Models. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Underwood, F. M. Describing long-term trends in precipitation using generalized additive models. Journal of hydrology.

- Haruna, A.; Blanchet, J.; Favre, A.-C. Performance-based comparison of regionalization methods to improve the at-site estimates of daily precipitation. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2022, 26, 2797–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. N. Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2011, 73, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mathworks, I. Symbolic Math Toolbox; 2024. https://www.mathworks.com/help/symbolic/.

- Sheppard, P. R.; Comrie, A. C.; Packin, G. D.; Angersbach, K.; Hughes, M. K. The climate of the US Southwest. Climate Research 2002, 21, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Mahoney, K. M.; Neiman, P. J.; Moore, B. J.; Alexander, M.; Ralph, F. M. The Landfall and Inland Penetration of a Flood-Producing Atmospheric River in Arizona. Part II: Sensitivity of Modeled Precipitation to Terrain Height and Atmospheric River Orientation. Journal of Hydrometeorology 2014, 15, 1954–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, M.; Collins, S.; Gutzler, D.; Moore, D. Regional trends and local variability in monsoon precipitation in the northern Chihuahuan Desert, USA. Journal of Arid Environments 2014, 103, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gochis, D. J.; Jimenez, A.; Watts, C. J.; Garatuza-Payan, J.; Shuttleworth, W. J. Analysis of 2002 and 2003 Warm-Season Precipitation from the North American Monsoon Experiment Event Rain Gauge Network. Monthly Weather Review 2004, 132, 2938–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremichael, M.; Vivoni, E. R.; Watts, C. J.; Rodríguez, J. C. Submesoscale Spatiotemporal Variability of North American Monsoon Rainfall over Complex Terrain. Journal of Climate 2007, 20, 1751–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaro, G.; Vivoni, E. R.; Gochis, D. J.; Watts, C. J.; Rodriguez, J. C. Temporal Downscaling and Statistical Analysis of Rainfall across a Topographic Transect in Northwest Mexico. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2014, 53, 910–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J. E. Variability of precipitation in an arid region: A survey of characteristics for Arizona; Institute of Atmospheric Physics, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ), 1956.

- Liebmann, B.; Bladé, I.; Bond, N. A.; Gochis, D.; Allured, D.; Bates, G. T. Characteristics of North American Summertime Rainfall with Emphasis on the Monsoon. Journal of Climate 2008, 21, 1277–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. D. D.; Jin, J. The response of future projections of the North American monsoon when combining dynamical downscaling and bias correction of CCSM4 output. Climate Dynamics, 2017; 49, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, E. The climatic factor as illustrated in arid America; Carnegie institution of Washington, 1914.

- Ellis, A. W.; Saffell, E. M.; Hawkins, T. W. A method for defining monsoon onset and demise in the southwestern USA. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2004, 24, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Franco, J. L.; Gray, L. J.; Osprey, S. The American monsoon system in HadGEM3 and UKESM1. Weather and Climate Dynamics 2020, 1, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. W.; Maddox, R. A.; Howard, K.; Reyes, S. The mexican monsoon. Journal of Climate 1993, 6, 1665–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X. Influence of the North American monsoon system on the US summer precipitation regime. Journal of climate 1997, 10, 2600–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; Mo, K.; Yao, Y. Interannual variability of the US summer precipitation regime with emphasis on the southwestern monsoon. Journal of Climate 1998, 11, 2582–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R. W.; Chen, Y.; Douglas, A. V. Interannual variability of the North American Warm Season Precipitation Regime. Journal of Climate 1999, 12, 653–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. L.; Ivanova, D.; Rabin, R.; Brown, T. J.; Redmond, K. Gulf of California sea surface temperatures and the North American monsoon: Mechanistic implications from observations. Journal of Climate 2002, 15, 2261–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrent, C.; Cavazos, T. Role of the land-sea thermal contrast in the interannual modulation of the North American Monsoon. Geophysical Research Letters 2009, 36, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, P. A.; Fu, R.; Mo, K. C. Decadal Variation of Rainfall Seasonality in the North American Monsoon Region and Its Potential Causes. Journal of Climate 2012, 25, 4258–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Hernandez, M.; Turrent, C.; Mayor, Y. G.; Tereshchenko, I. Using Observational and Reanalysis Data to Explore the Southern Gulf of California Boundary Layer During the North American Monsoon Onset. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 2021; 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, A. M.; Carpenter, D. A.; Weser, P. J. Mechanisms of interannual variability of the southwest United States summer rainfall maximum. Journal of Climate 1990, 3, 999–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, S.; Ullrich, P.; Boos, W. R. Meteorological Drivers of North American Monsoon Extreme Precipitation Events. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. [CrossRef]

- Bryson, R. A.; Lowry, W. P. Synoptic Climatology of the Arizona Summer Precipitation Singularity *, #. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 1955, 36, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantz, K.; Rajagopalan, B.; Clark, M.; Zagona, E. Seasonal Shifts in the North American Monsoon. Journal of Climate 2007, 20, 1923–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, T. M.; Crimmins, M. A.; Bertelsen, C. D. Onset of summer flowering in a ‘Sky Island’ is driven by monsoon moisture. New Phytologist 2011, 191, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drezner, T. D. How long does the giant saguaro live? Life, death and reproduction in the desert. Journal of Arid Environments 2014, 104, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, F.; Benito, B.; Rodriguez, M. Á. M.; Gray, C. Potential changes in the distribution of Carnegiea gigantea under future scenarios. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5623. [Google Scholar]

- Félix-Burruel, R. E.; Larios, E.; González, E. J.; Búrquez, A. Episodic recruitment in the saguaro cactus is driven by multidecadal periodicities. Ecology 2021, 102, e03458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombardi, R. J.; Carvalho, L. M. V. IPCC global coupled model simulations of the South America monsoon system. Climate Dynamics 2009, 33, 893–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Station Name | Station ID | Network | Period of Record Used | Elev. (m) | Latitude | Longitude | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alamo Tank | 2080 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2022 | 1212 | 32.2797 | -110.6350 |

| 2 | Alamo Wash/Glenn St | 2370 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2008, 2010-2021 | 745 | 32.2587 | -110.8841 |

| 3 | Avra Valley Air Park/Santa Cruz R | 6110 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2000, 2002-2022 | 606 | 32.4290 | -111.2251 |

| 4 | Catalina State Park | 1070 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1991-2021 | 825 | 32.4235 | -110.9161 |

| 5 | Cherry Tank | 1050 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2021 | 1232 | 32.5181 | -110.8370 |

| 6 | Davidson Canyon | 4310 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2022 | 1057 | 31.9936 | -110.6451 |

| 7 | Diamond Bell Ranch | 6410 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-1999, 2001-2022 | 994 | 31.9897 | -111.2972 |

| 8 | Dodge Tank | 1040 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2020 | 1013 | 32.5119 | -110.8642 |

| 9 | Elephant Head | 6350 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2022 | 1062 | 31.7250 | -110.9678 |

| 10 | Empire | 021205 | RAWS4 | 1990-2011, 2013-2016, 2018-2022 | 1393 | 31.7806 | -110.6347 |

| 11 | Italian Trap | 2030 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990, 1992-2022 | 1254 | 32.2853 | -110.5636 |

| 12 | Keystone Peak | 6310 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2021 | 1877 | 31.8769 | -111.2150 |

| 13 | Mount Lemmon | 1090 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2022 | 2790 | 32.4427 | -110.7885 |

| 14 | Oracle R.S. CDO | 1020 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2019, 2021 | 1436 | 32.5855 | -110.7868 |

| 15 | Oracle Ridge | 1030 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2021 | 1963 | 32.5328 | -110.7562 |

| 16 | Organ Pipe Cactus NM | USC00026132 | NCEI2 | 1990-2001, 2003-2022 | 512 | 31.9555 | -112.8002 |

| 17 | Pantano Vail | 4250 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990, 1992-2019, 2022 | 982 | 32.0361 | -110.6767 |

| 18 | Pig Springs | 1060 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2022 | 1463 | 32.5261 | -110.7948 |

| 19 | Ranch Rd | 2050 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-1993, 1995-2022 | 1312 | 32.3103 | -110.6061 |

| 20 | Rincon | 021207 | RAWS4 | 1995-1999, 2002-2022 | 2482 | 32.2056 | -110.5481 |

| 21 | Sabino Dam | 2160 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1991-2022 | 834 | 32.3147 | -110.8106 |

| 22 | Saguaro | 021202 | RAWS4 | 2002-2022 | 890 | 32.3167 | -110.8133 |

| 23 | Santa Cruz R/Canoa Ranch | 6060 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2022 | 917 | 31.7447 | -111.0372 |

| 24 | Santa Cruz R/Continental Rd | 6050 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2021 | 866 | 31.8542 | -110.9792 |

| 25 | Santa Cruz R/Ina Rd | 6020 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2000, 2002-2022 | 659 | 32.3372 | -111.0800 |

| 26 | Santa Cruz R/Valencia Rd | 6040 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-1996, 1998-2021 | 752 | 32.1342 | -110.9919 |

| 27 | Sasabe | 021206 | RAWS4 | 1992-2022 | 1007 | 31.6908 | -111.4500 |

| 28 | Sells | 021209 | RAWS4 | 2005-2006, 2008-2009, 2011-2022 | 714 | 31.9100 | -111.8975 |

| 29 | Tanque Verde Guest Ranch | 2090 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-1992,1994-2008, 2010-2021 | 832 | 32.2458 | -110.6827 |

| 30 | Tanque Verde Sabino Bridge | 2120 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-2000, 2001-2010, 2011-2022 | 756 | 32.2653 | -110.8414 |

| 31 | Tinaja Ranch | 6320 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990, 1992, 1994-2022 | 1194 | 31.8381 | -111.1483 |

| 32 | Tucson Int’l Airport | USW00023160 | NCEI2 | 1990-2022 | 778 | 32.1315 | -110.9564 |

| 33 | White Tail | 2150 | Pima Co. ALERT1 | 1990-1992, 1994-2022 | 2493 | 32.4136 | -110.7319 |

| Station | DOY onset | Monsoon Rainfall (MR, mm) | Annual Rainfall (AR, mm) | Monsoon Proportion of Annual Rainfall (PAR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alamo Tank | 117.58 | 167.40 | 345.44 | 0.48 |

| 2 | Alamo Wash below Glenn St | 123.36 | 131.23 | 244.69 | 0.54 |

| 3 | Avra Valley Air Park - Santa Cruz Basin | 128.79 | 98.29 | 199.32 | 0.49 |

| 4 | Catalina State Park | 115.64 | 178.18 | 348.69 | 0.51 |

| 5 | Cherry Spring | 117.85 | 192.16 | 379.87 | 0.51 |

| 6 | Davidson Canyon | 112.42 | 210.89 | 360.39 | 0.59 |

| 7 | Diamond Bell | 119.67 | 148.17 | 249.32 | 0.59 |

| 8 | Dodge Tank | 120.94 | 171.17 | 343.37 | 0.50 |

| 9 | Elephant Head | 112.79 | 191.82 | 306.42 | 0.63 |

| 10 | Empire | 112.19 | 240.36 | 359.13 | 0.67 |

| 11 | Italian Trap | 114.94 | 208.11 | 393.66 | 0.53 |

| 12 | Keystone Peak | 110.21 | 219.48 | 328.28 | 0.67 |

| 13 | Mount Lemmon | 109.21 | 411.99 | 809.18 | 0.51 |

| 14 | Oracle Ranger Stn at Canada del Oro | 119.30 | 178.23 | 356.17 | 0.50 |

| 15 | Oracle Ridge | 111.64 | 262.55 | 480.58 | 0.55 |

| 16 | Organ Pipe Cactus NM | 126.24 | 111.49 | 234.81 | 0.47 |

| 17 | Pantano Vail | 121.55 | 151.58 | 244.53 | 0.62 |

| 18 | Pig Springs | 117.33 | 215.57 | 451.81 | 0.48 |

| 19 | Ranch Road | 117.58 | 177.29 | 360.22 | 0.49 |

| 20 | Rincon | 109.69 | 349.48 | 574.48 | 0.61 |

| 21 | Sabino Dam | 121.47 | 149.06 | 302.59 | 0.49 |

| 22 | Saguaro | 120.19 | 169.61 | 309.14 | 0.55 |

| 23 | Santa Cruz River at Canoa Ranch | 117.42 | 173.03 | 271.15 | 0.64 |

| 24 | Santa Cruz River at Continental Rd | 119.42 | 147.73 | 243.46 | 0.61 |

| 25 | Santa Cruz River at Ina Road | 129.18 | 106.19 | 204.48 | 0.52 |

| 26 | Santa Cruz River at Valencia Road | 126.27 | 114.23 | 208.66 | 0.55 |

| 27 | Sasabe | 112.40 | 210.67 | 334.04 | 0.63 |

| 28 | Sells | 113.45 | 155.26 | 251.99 | 0.62 |

| 29 | Tanque Verde Guest Ranch | 115.91 | 174.43 | 328.58 | 0.53 |

| 30 | Tanque Verde Sabino Bridge | 123.21 | 130.59 | 240.29 | 0.54 |

| 31 | Tinaja Ranch | 115.26 | 189.03 | 310.90 | 0.61 |

| 32 | Tucson Int'l Airport | 121.36 | 154.09 | 273.47 | 0.56 |

| 33 | White Tail | 108.97 | 399.27 | 758.54 | 0.53 |

| Grand Total/Mean | 117.58 | 167.40 | 345.44 | 0.48 |

| Model/Test | Response | Statistic | Value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAM | DOY Onset | Deviance explained | 19.1% | |

| LRM | R2 | 0.032 | <0.001 | |

| SRM | R2 | 0.176 | <0.001 | |

| MK Trend | 0.511 | |||

| GAM | Monsoon Rainfall | Deviance explained | 13.3% | <0.001 |

| LRM | R2 | 0.022 | <0.001 | |

| SRM | R2 | 0.084 | ||

| MK Trend | 0.654 | |||

| GAM | Annual Rainfall | Deviance explained | 5.4% | <0.001 |

| LRM | R2 | <0.001 | 0.830 | |

| SRM | R2 | 0.038 | ||

| MK Trend | 0.861 | |||

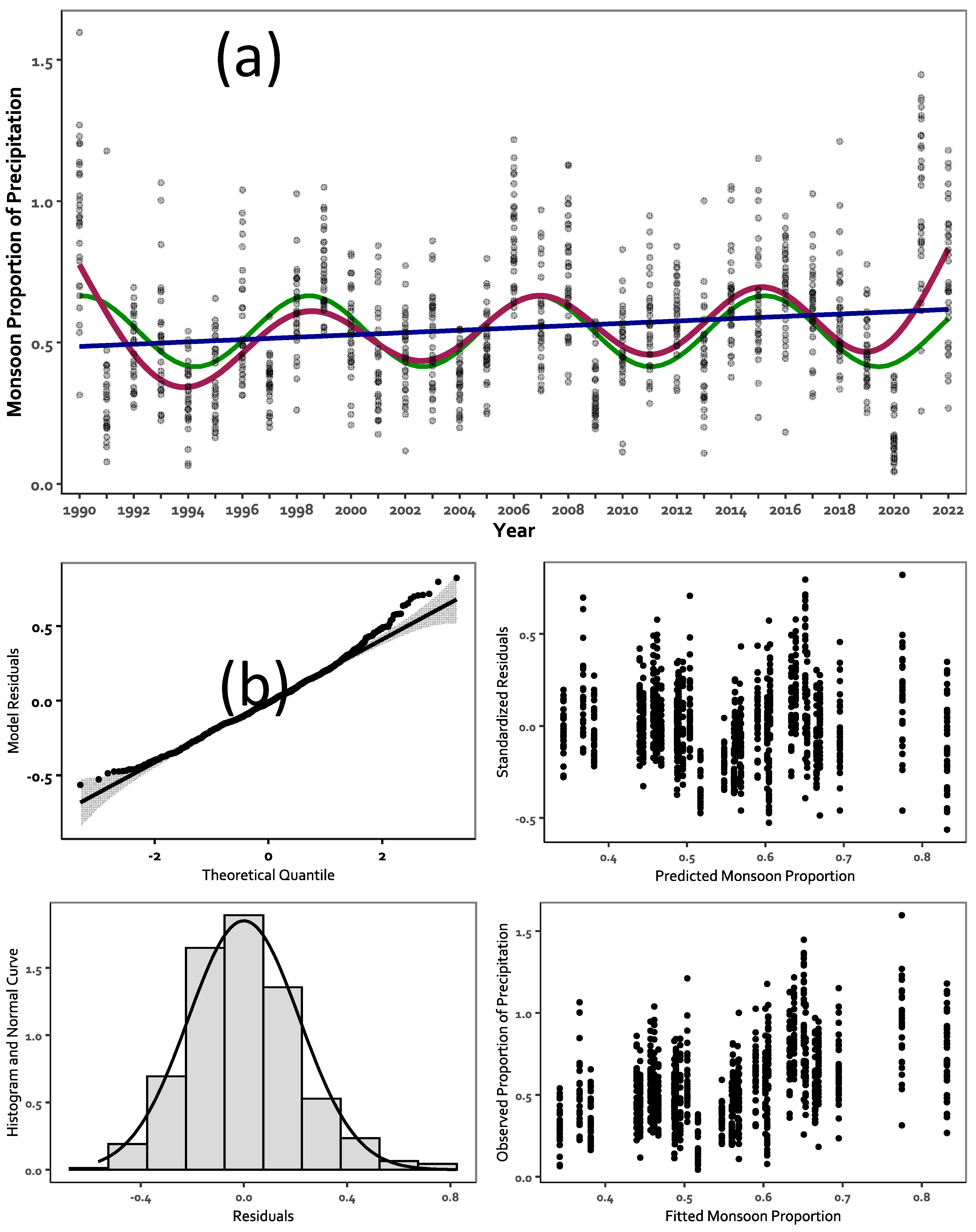

| GAM | Monsoon Rainfall Proportion of Annual | Deviance explained | 21.4% | <0.001 |

| LRM | R2 | 0.025 | <0.001 | |

| SRM | R2 | 0.174 | ||

| MK Trend | 0.052 |

| Variable | Crest | Trough | Amplitude (Crest-Trough) | Period, Mean Crest->Crest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOY onset | 1994/05/09 | 1999/08/07 | 30 days | 3140 days 8.6 years |

| 2004/01/06 | 2008/03/28 | 18 days | ||

| 2011/10/05 | 2015/11/09 | 14 days | ||

| 2020/02/22 | ||||

| MR | 1998/07/06 | 1993/10/11 | 97 mm | 3039 days 8.3 years |

| 2006/12/17 | 2002/08/10 | 82 mm | ||

| 2015/02/25 | 2010/12/05 | 90 mm | ||

| 2018/12/29 | 89.667 | |||

| AR | 1999/05/06 | 1995/12/14 | 39 mm | 3050 days 8.4 years |

| 2007/07/15 | 2003/04/01 | 44 mm | ||

| 2016/01/18 | 2011/04/01 | 43 mm | ||

| 2019/10/05 | ||||

| PAR | 1998/09/14 | 1993/11/03 | 27 pct | 2969 days 8.1 years |

| 2006/12/17 | 2002/08/10 | 23 pct | ||

| 2014/12/17 | 2010/12/29 | 24 pct | ||

| 2018/12/29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).