Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

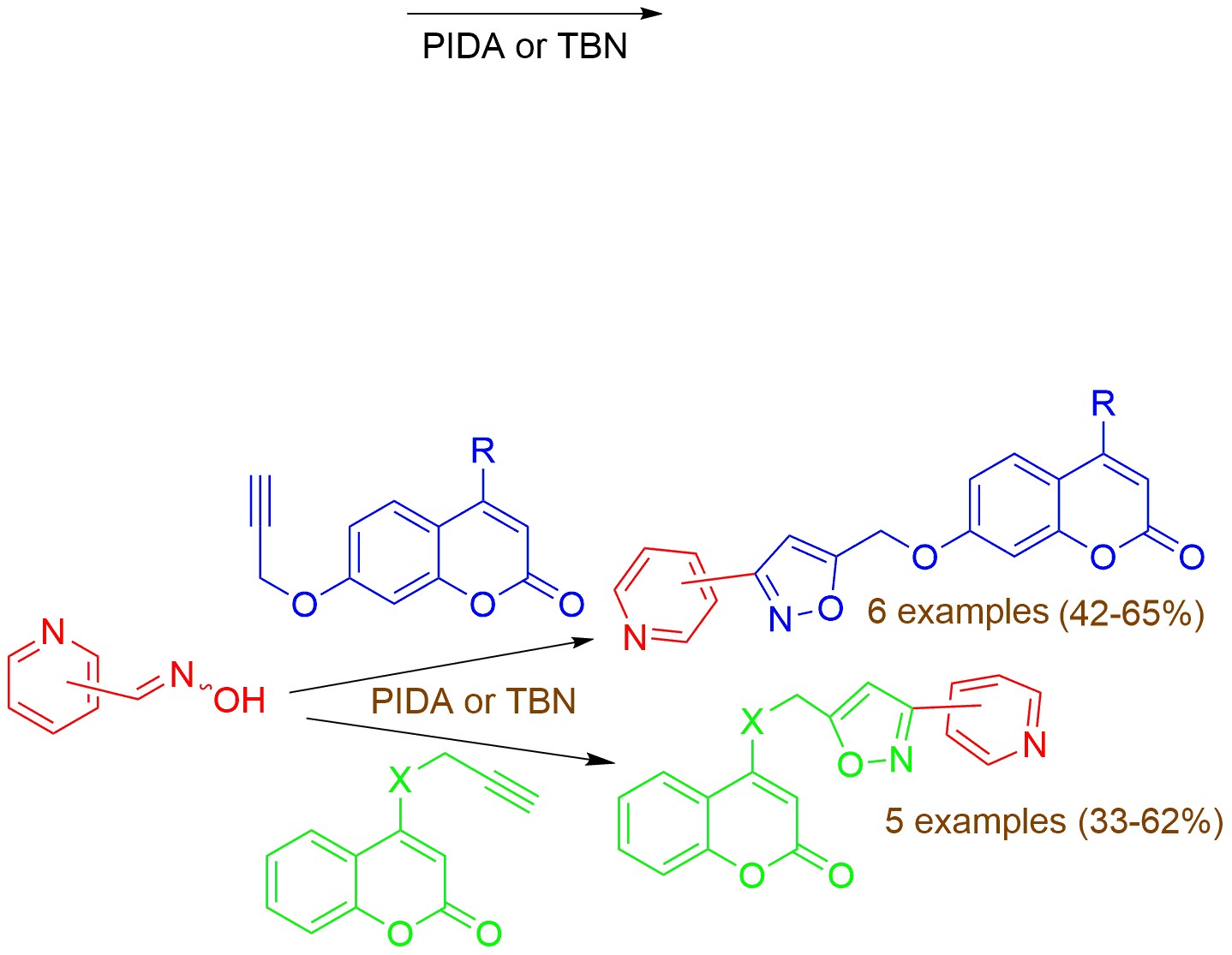

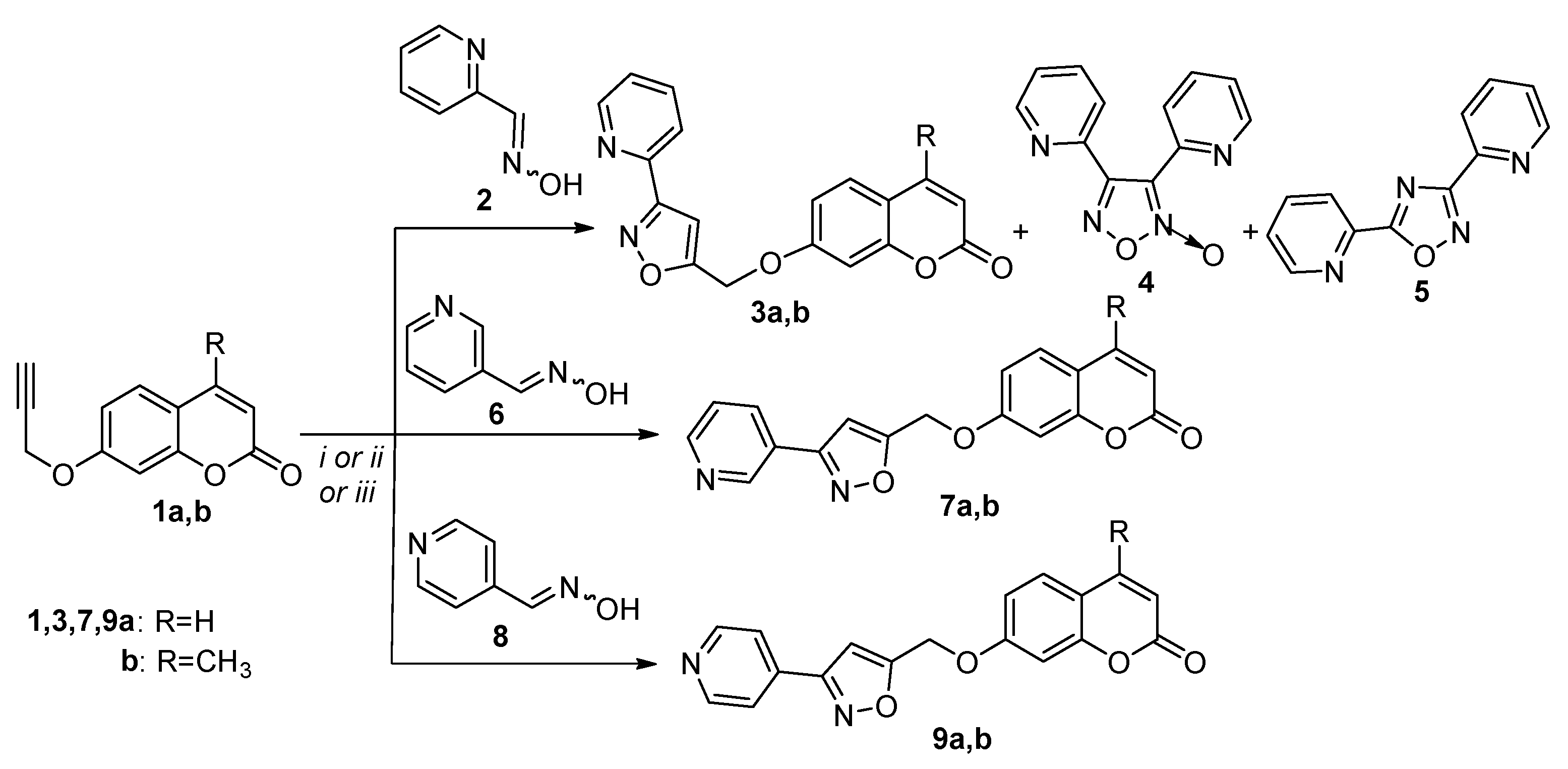

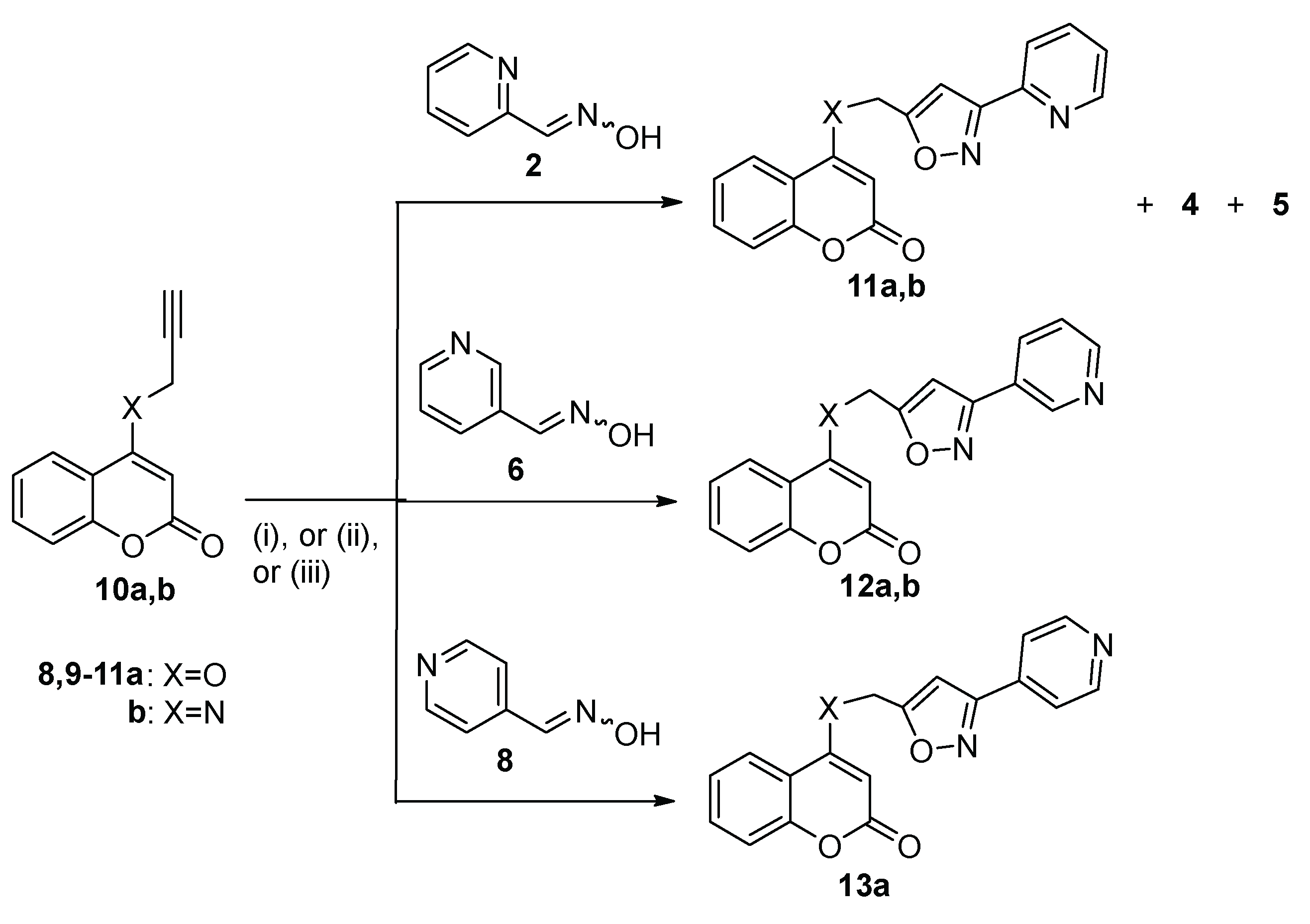

The 1,3 -dipolar cycloaddition reaction of nitrile oxides, prepared in situ from pyridine aldehyde oximes, with propargyloxy- or propargylaminocoumarins afforded the corresponding new 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoles in moderate to good yields. As oxidants for the formation of nitrile oxides utilized (diacetoxyiodo)benzene (PIDA) at room temperature or under microwave irradiation or tert-butyl nitrite (TBN) under reflux. Preliminary in vitro screening tests for some biological activities of the new compounds have been performed. Compounds 12b and 13a are potent LOX inhibitors with IC50 5 μΜ and 10 μΜ, respectively, while hybrids 12b and 13a exhibit moderate to low anticancer activities on Hela, HT-29, and H1437 cancer cells.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.2. Biology

2.3. Biochemistry

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Chemistry

3.2.1. General Procedure of the 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions of Propargyl Coumarins with Pyridine Aldoximes. Synthesis of (3-(pyridin-2-yl)isoxazol-5-yl)methoxy)-2H-chromen-2-one (3a)

3.3. Biological Experiments

3.3.1. Inhibition of Linoleic Acid Peroxidation

3.3.2. Soybean Lipoxygenase Inhibition Study

3.4. Biochemical Experiments

3.4.1. Cell Culture

3.4.2. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| TLC | Thin Layer Chromatography |

References

- Preliminary communications presented at 23th Panhellenic Chemistry Conference, Athens Greece, September, 25-28, 2024.

- Elmusa, S.; Elmusa, M.; Elmusa, B.; Kasimogullari, R. Coumarins: Chemical Synthesis, Properties and Applications. Duzce University J. Sci. Techn. 2025, 13, 131–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citarella, A.; Vittorio, S.; Dank, C.; Ielo, L. Syntheses, reactivity, and biological applications of coumarins. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1362992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Peña, L.; Matos, M.J.; López, E. Recent Advances in Biologically Active Coumarins from Marine Sources: Synthesis and Evaluation. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Morales, V.; Villasana-Ruíz, A.P.; Garza-Veloz, I.; González-Delgado, S.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. Therapeutic Effects of Coumarins with Different Substitution Patterns. Molecules 2023, 28, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A.; Matos, M.J.; Uriarte, E.; Santana, L. Trending Topics on Coumarin and Its Derivatives in 2020. Molecules 2021, 26, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain,M. I.; Syed, Q.A.; Khattak, M.N.K.; Hafez, B.; Reigosa, M.J.; El-Keblawy, A. Natural Product Coumarins: Biological and Pharmacological Perspectives. Biologia 2019, 74, 863–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.J.; Santana, L.; Uriarte, E.; Abreu, O.A.; Molina, E.; Yord, E.G. Coumarins—An Important Class of Phytochemicals. In Phytochemicals—Isolation, Characterisation and Role in Human Health; Rao, V., Rao, L., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2015; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- O’Kennedy, R.; Thornes, R.D. Coumarins: Biology, Applications and Mode of Action; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sharapov, A.D.; Fatykhov, R.F.; Khalymbadzha, I.A.; Zyryanov, G.V.; Chupakhin, O.N.; Tsurkan, M.V. Plant Coumarins with Anti-HIV Activity: Isolation and Mechanisms of Action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqib, M.; Khatoon, S.; Ali, M.; Sajid, S.; Assiri, M. A.; Ahamad, S.; Saquib, M.; Hussain, M. K. Exploring the anticancer potential and mechanisms of action of natural coumarins and isocoumarins. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 282, 117088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshibl, H.M.; Al-Abdullah, E.S.; Haiba, M.E.; Alkahtani, H.M.; Awad, G.E.A.; Mahmoud, A.H.; Ibrahim, B.M.M.; Bari, A.; Villinger, A. Synthesis and Evaluation of New Coumarin Derivatives as Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fylaktakidou, K.C.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.J.; Litinas, K.E.; Nicolaides, D.N. Natural and synthetic coumarin derivatives with anti-inflammatory/antioxidant activities. Curr. Pharm. Design 2004, 10, 3813–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Mageed, M. M. A.; Ezzat, M. A. F.; Moussa, S. A.; Abdel-Aziz, H. A.; Elmasry, G. F. Rational design, synthesis and computational studies of multi-targeted anti-Alzheimer’s agents integrating coumarin scaffold. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 154, 108024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, K.; shima, K.; Korogi, S.; Kotematsu, N.; Morinaga, O. Locomotor-reducing, sedative and antidepressant-likeeffects of confectionary flavours coumarin and vanillin. Biol. Phar. Bull. 2024, 47, 1768–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, C. R.; Sahoo, J.; Mahapatra, M.; Lenka, D.; Sahu, P. K.; Dehury, B.; Padhy, R. N. Paidesetty, S. K. Coumarin derivatives as promising antibacterial agent(s). Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keri, R. S.; Budagumpi, S.; Balappa Somappa, S. Synthetic and natural coumarins as potent anticonvulsant agents: a review with structure–activity relationship. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2022, 47, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.S.; Kongot, M.; Kumar, A. Coumarin hybrid derivatives as promising leads to treat tuberculosis: Recent developments and critical aspects of structural design to exhibit anti-tubercular activity. Tuberculosis 2021, 127, 102050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperkiewicz, K.; Ponczek, M.B.; Owczarek, J.; Guga, P.; Budzisz, E. Antagonists of Vitamin K—Popular Coumarin Drugs and New Synthetic and Natural Coumarin Derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, S. N.; Damavandi, M. S.; Sadeghi, P.; Nazifi, Z.; Salari-Jazi, A.; Massah, A. R. Synthesis of some novel coumarin isoxazole sulfonamide, 3D-QSAR studies, and antibacterial evaluation. Scient. Rep. 2021, 11, 20088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.; Ahmed, N.; Alsharif. M. A.; Alahmdi, M. I.; Mukhtar, S. PhI(OAc)2-Mediated One-Pot Synthgesis and their antibacterial activity of flavone and coumarin based isoxazoles under mild reaction conditions. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 1872–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, K. R. A.; Abdelgawad, M. A.; Elshemy, H. A. H.; Kahk, N. M.; El Amir, D. M. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2017, 14, 773–781.

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.-B.; Sui, L.-L.; Luan, T. Natural products-isoxazole hybrids: A review of developments in medicinal chemistry. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Hu, J.; Bao, N.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Sun, J. Design, synthesis and cytotoxic activities of scopoletin-isoxazole and scopoletin-pyrazole hybrids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2017, 27, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, G. X.; Niu, C.; Mamat, N.; Aisa, H. A. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of novel coumarin derivatives containing isoxazole moieties on melanin synthesis in B16 cells and inhibition on bacteria. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett, 2017, 27, 26674–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Kumari, P.; Pstel, N. B. Synthesis and biological evaluation of coumarin based isoxazoles, pyrimidinethiones and pyrimidin-2-ones. Arab J. Chem. 2017, 10, S3990–S4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayane, M.; Rahmouni, A.; Daami-Remadi, M.; Mansour, M. B.; Romdhane, A.; Jannet, H. B. Design and synthesis of antimicrobial, anticoagulantand anticholinesterase hybrid molecules from 4-umbelliferone. J. Enz. Inh. Med. Chem. 2016, 31, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koley, M. Han, J.; Soloshonok, V. A.; Mojumder, S.; Javahershenas, R.; Makarem, A.; Latest developments in coumarin-based anticancer agents: mechanism of action and structure-activity relationship studies. RSC Med. Chem 2024, 15, 10–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorababu, A. Coumarin-heterocycle framework: A privileged approach in promising anticancer drug design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2021, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, I.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. Hybrids of coumarin derivatives as potent and multifunctional bioactive agents: A review. Med. Chem. 2020, 16, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.; Poyraz, S.; Ersatir, M. Recent advances on biologically active coumarin-based hybrid compounds. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 617–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashidhara, K. V.; Modukuri, R. K.; Choudhary, D.; Rao, K. B.; Kumar, M.; Khedgikar, V.; Trivedi, R. Synthesis and evaluation of new coumarin-pyridine hybrids with promising anti-osteoporotic activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 70, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Aroosh, A.; Islam, A.; Kalsoom, S.; Ahmad, F.; Hameed, S.; Abbasi, S. W.; Yasinzai, M.; Naseer, M. M. Novel coumarin-isatin hybrids as potent antileishmanial agents: Synthesis, in silico and in vitro evaluations. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 110, 104816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chanda, K. An overview on metal-free synthetic routes to isoxazoles: the privileged scaffold. RSC Adv., 2021, 11, 32680–32705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subi, S.; Rose, S. V.; Reji, T. F. A. F. Synthesis, Characterization, DFT-study, molecular Modelling, and Biological evaluation of Novel 4-Aryl-3-(pyridine-3-yl)isoxazole Hybrids as Potent Anticancer Agents with Inhibitory Effect on Scin Cancer. Asian J. Chem. 2021, 33, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, D. X.; Dung, V. C. Recent progress in the synthesis of isoxazoles. Curr. Org. Chem. 2021, 25, 2938–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J. K.; Denton, T. T.; Cerny, M. A.; Zhang, X.; Johnson, E. F.; Cashman, J. R. Synthetic Inhibitors of Cytochtome P-450 2A6: Inhibitory activity, Difference spectra, Mechanism of Inhibition, and Protein Cocrystallization. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6987–7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisgen, R. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition. Past and Future. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1963, 2, 565–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugst, M.; Reissig, H.-U. The Huisgen reaction: Milestones of the 1,3-Cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 12293–12307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R. K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, V.; Dey, A.; Patlolla, R. R.; Burra, A. G.; Khatravath, M. PIDA Mediated synthesis of benzopyranoisoxazoles via an intramolecular nitrile oxide cycloaddition (INOC): Application to the synthesis of 4H-chromeno[4,3-c]isoxazol-4-ones. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2023, 12, e202300410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, J.; Sydney, S.; Rajapaske, H.; Saffiddine, M.; Reyes, V.; Denton, R. W. A facile synthesis of some bioactive isooxazoline dicarboxylic acids via microwave-assisted 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. Reactions 2024, 5, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cheng, H.; Khan, S.; Xiao, G.; Rong, l.; Bai, C. Development of coumarine derivatives as potent anti-filovirus entry inhibitors targeting viral glycoprotein. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 204, 112595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lan, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, M.; Liu, B.F.; Zhang, G. Synthesis and evaluation of new coumarin derivatives as potential atypical antipsychotics. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 74, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Shin, S.; Park, K.C.; Jeong, E.; Park, J.H. Synthesis and in vitro assay of new triazole linked decursinol derivatives showing inhibitory activity against cholinesterase for Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 2016, 60, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, L.; Kumar, P.S.V.; Onkar, P.; Srinivas, L.; Pydisetty, Y.; Chandramouli, G.V.P. Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of dihydro-6H-chromeno[4,3-b]isoxazolo [4,5-e]pyridine derivatives as potent antidiabetic agents. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2017, 43, 5433–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, S.; Borah, P.; Bhujan, P. J. Intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions in the synthesis of complex annelated quinolines, α-carbolines and coumarins. Mol. Divers. 2012, 16, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallitsakis,M. G.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. J.; Litinas, K. E. Synthesis of purine homo-N-nucleosides modified with coumarins as free radicals scavengers. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 765–775. [CrossRef]

- Kallitsakis, M. G.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. J.; Peperidou, A.; Litinas, K. E. Synthesis of 4-hydroxy-3-[(E)-2-(6-substituted-9H-purin-9-yl)vinyl]coumarins as lipoxygenase inhibitors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallitsakis, M. G.; Yanez, M.; Soriano, E.; Marco-Contelles, J.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. J.; Litinas, K. E. Purine Homo-N-Nucleoside+Coumarin Hybrids as Pleiotropic Agents for the Potential Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douka, M. D.; Sigala, I. M.; Nikolakaki, E.; Prousis, K. C.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D. J.; Litinas, K. E. Cu-Catalyzed synthesis of coumarin-1,2,3-triazole hybrids connected with quinoline or pyridine framework. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wei, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, X.; Lei, K.; Zhou, M. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking studies of phenylpropanoid derivatives as potent ant-hepatitis B virus agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 95, 473–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiova, I.; Kovackova, S.; Kois, P. Synthesis of coumarin-nucleoside conjugates via Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, R. H.; Wakefield, B. J. J. Org. Chem. 1960, 25, 546–551. [CrossRef]

- Stephens, C.E.; Arafa, R. K. 3,5-Diarylisoxazoles: Individualized three-step synthesis and isomer determination using 13C NMR or Mass Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outirite, M.; Lebrini, M.; Lagrenee, M.; Bentiss, F. New one step synthesis of 3,5-disubstituted 1,2,4-oxadiazoles. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2007, 44, 1529–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touaux, B.; Texier-Boullet, F.; Hamelin, J. Synthesis of oximes, conversion to nitrile oxides and their subsequent 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions under microwave irradiation and solvent-free reaction conditions. Heteroatom Chem. 1998, 9, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedus, A.; Cwik, A.; Hell, Z.; Horvath, Z.; Esek, A.; Uszoki, M. Green Chem. 2002, 4, 618–620. [CrossRef]

- Pooja; Aggarval, S. ; Tiwari, A. K.; Kumar, V.; Pratap, R.; Singh, G.; Mishra, A. K. Novel pyridinium oximes: synthesis molecular docking and in vitro reactivation studies. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 23471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C. P.; Srimannarayana, G. Claisen rearrangement of 4-propargyloxycoumarins: Formation of 2H, 5H-pyrano[3,2-c][1]benzopyran-5-ones. Synthetic Commun. 1990, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. A.; Tan, Y. T. Efficient synthesis of pyrido[3,2-c]coumarins via silver nitrate catalyzed cycloisomerization and application to the first synthesis of polyneomarline C. Synthesis 2019, 51, 4611–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, T.S.; Hadjipavlou-Litina, D.J.; Litinas, K.E. . Synthesis Through Three-Component Reactions Catalyzed by FeCl3 of Fused Pyridocoumarins as Inhibitors of Lipid Peroxidation. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2014, 51, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, I.; Tsamis, K. I.; Gousia, A.; Alexiou, G.; Voulgaris, S.; Giannakouros, T.; Kyritsis, A. P.; Nikolakaki, E. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 8699–8707. [CrossRef]

| Entry | Oxime | Propagylcoumarin | Method[a] | Temperature | Time | Products (% yield) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1a | A | r. t. | 1 h | 3a (60), 4 (20) |

| 2 | 2 | 1a | B | 120°C | 1 h | 3a (48), 4 (16), 5 (9) |

| 3 | 2 | 1a | C | Reflux | 18 h | 3a (34), 5 (32) |

| 4 | 2 | 1b | A | r. t. | 15 h | 3b (65), 4 (17) |

| 5 | 2 | 1b | B | 120°C | 1 h | 3b (43), 4 (17), 5 (11) |

| 6 | 2 | 1b | C | Reflux | 18 h | 3b (44), 4 (15), 5 (13) |

| 7 | 6 | 1a | C | Reflux | 18 h | 7a (61) |

| 8 | 6 | 1b | C | Reflux | 18 h | 7b (53) |

| 9 | 8 | 1a | A[b] | Reflux | 2 d | 9a (24) |

| 10 | 8 | 1a | C | Reflux | 18 h | 9a (42) |

| 11 | 8 | 1b | C | Reflux | 18 h | 9b (45) |

| 12 | 2 | 10a | B | 100°C | 1 h | 11a (44), 4 (27) |

| 13 | 2 | 10a | C | Reflux | 18 h | 11a (62), 4 (5), 5 (11) |

| 14 | 2 | 10b | B | 100°C | 2 h | 11b (55) |

| 15 | 6 | 10a | A[b] | Reflux | 2 d | 12a (30) |

| 16 | 6 | 10a | C | Reflux | 18 h | 12a (33) |

| 17 | 6 | 10b | C | Reflux | 18 h | 12b (56) |

| 18 | 8 | 10a | A[b] | Reflux | 2 d | 13a (55) |

| 19 | 8 | 10a | C | Reflux | 18 h | 13a (40) |

|

Entry |

Compoundsa | Clog P b | LOX (%)/IC50 µM |

ILPO (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3a | 2.27 | no | 66 |

| 2 | 3b | 2.77 | no | 0.6 |

| 3 | 7a | 2.27 | 10 µM | 42 |

| 4 | 7b | 2.27 | no | 2 |

| 5 | 9a | 2.77 | 38 | 83.6 |

| 6 | 9b | 2.77 | no | 86.6 |

| 7 | 11a | 2.27 | no | 86 |

| 8 | 11b | 1.95 | no | 66 |

| 9 | 12a | 2.01 | 10 | 72 |

| 10 | 12b | 1.95 | 18 | 90.4 |

| 11 | 13a | 2.01 | 5 µM | 44.6 |

| 12 | NDGA | 0.45 μΜ | ||

| 13 | Trolox | 93 |

| EC50 (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Compound | HeLa | HT-29 | H1437 |

| 1 | 7a | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 2 | 9a | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 3 | 12b | 38.1 | 96.5 | 47.3 |

| 4 | 13a | 44.2 | 65.8 | 74.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).