1. Introduction

Due to the observed climate changes, it is necessary to take care of the environment [

1,

2]. There is a need to adapt the construction industry to changing standards in the field of sustainable development related to the circular economy (CE) [

3,

4], reducing energy consumption [

5,

6,

7,

8] and reducing the carbon footprint [

9]. It is estimated that the construction sector is currently responsible for about 35% of global energy consumption and about 38% of global carbon dioxide (CO

2) emissions [

10]. The production of building materials accounts for about 10% of the above [

11]. Therefore, it is necessary to search for new technological, material and construction solutions [

12,

13,

14]. This can be considered in two aspects: production (carbon footprint, energy consumption, recycling and waste management, etc.) and use (energy consumption when using these products, e.g. building material [

15,

16]). The material that combines both of the above aspects seems to be foamed concrete. It should be noted here that foamed concrete has been known for over 100 years [

17]. However, only recently has foamed concrete developed due to the development of foaming agents and the development of machines for the production of foamed concrete. It is associated with the development in the field of chemistry and technology of machines for the production of building materials, respectively.

Foamed concrete is defined as lightweight concrete, in which the volume content of air voids is at least 20% [

18,

19,

20], produced by the pre-foaming method or in the mixing process [

21,

22,

23]. Foamed concrete (FC) is classified as lightweight concrete with density ranging from 280 to 1800 kg/m

3 [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The thermal conductivity coefficient ranges from about 0.1 to 0.7 W/(m∙K) for foamed concrete with density ranging from 600 to 1600 kg/m

3 [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. The main advantages of foamed concrete are low weight, good insulating properties and relatively good compressive strength [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

The decisive factor for foamed concrete, as well as other cement composites, is cement. The distinguishing factor for foamed concrete is the foaming agent from which the foam is produced. The selection of foaming agents plays a key role in the production of stable foam with good properties [

41,

42,

43,

44], which is the basis for the production of foamed concrete with good properties [

45,

46,

47]. Foaming agents can be divided into: natural agents based on protein, animal or plant origin [

48,

49,

50] and synthetic agents [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55].

Foamed concrete produced on the basis of synthetic foaming agents is less frequently presented in the literature [

56,

57,

58]. This may be related to the problem of their compatibility with other admixtures in the alkaline environment of the cementitious mix, as well as compatibility with the cementitious mix itself [

59,

60]. For this reason, a foaming agent based on natural protein is much more often used to produce foamed concrete [

38,

61,

62]. It is assumed that foam based on natural foaming agents is characterized by greater stability [

59,

63,

64]. This ensures the stability of the porous structure at the hardening stage [

65]. As a result, foamed concrete produced from foaming agents based on natural proteins is characterized by a higher air content, i.e. lower density [

66,

67]. In the literature, it can be found that foamed concrete produced from a natural foaming agent is characterized by higher compressive strength [

59,

68] even by over 60-80% [

19,

63,

69]. However, Sun et al. [

42] obtained about 43% and 11% higher compressive strength for foamed concrete on a synthetic basis compared to foamed concrete on a natural basis, made from plant and animal protein (animal blood), respectively. Falliano et al. [

63] obtained significantly higher compressive strength for foamed concrete with a density of about 400 to 850 kg/m

3, produced on the basis of a protein foaming agent than on the basis of a synthetic foaming agent. This is consistent with the results of the research by Gołaszewski et al. [

70] conducted for foamed concrete with a density lower than 400 kg/m

3. This effect was much more pronounced than that observed by Panesar [

59] for foamed concrete with medium and high density.

Hou et al. [

71] conducted comparative studies for different types of foaming agents. They tested foamed concrete based on cationic surfactant (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide CTAB), anionic surfactant (SDS), hydrolysed animal protein (HP) and non-ionic surfactant (OP-10 emulsifier). However, these studies concern only properties of foamed concrete mix and microstructures of hardened foamed concrete.

Therefore, the aim of this article is to compare the properties of foamed concretes of the same density but produced from different recipes, where the basic difference is the use of foaming agents of different origin (synthetic and organic). The tests were carried out for three target densities of hardened foamed concrete (600, 800 and 1000 kg/m3). The tests were carried out for samples of the same densities, but the samples differ in: 1) components, including synthetic (I) and protein foaming agent (II), 2) method of production: foam generator (I), foamed concrete production machine (II). Density, porosity, and mechanical properties were tested. Moreover, the microstructure of hardened foamed concrete was determined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation and Mix Composition and Production of Foamed Concrete Based on Synthetic Foaming Agent

The following ingredients were used to conduct the study: Portland cement; tap water and synthetic foaming agent. Class of Portland cement according to EN 197-1:2011 [

72] was CEM I 42.5R.

Specimens of foamed concrete with three different densities were produced (see

Table 1). The densities of hardened foamed concrete were about 600, 800 and 1000 kg/m

3 with a tolerance of ±50 kg/m

3, marked as FC600-S, FC800-S and FC1000-S respectively. A commercial liquid polymer admixture with specific gravity of 1.02 g/cm

3 was used as synthetic foaming agent (MEEX, Chrzanów, Poland). The synthetic foaming agent contents were 8.0, 5.0 and 4.0% of cement mass. Based on previous research work by the authors [

53,

54,

55], a constant

weff/c ratio was set at 0.44 for all specimens, where

weff is the water content, including tap water and liquid foaming agent; c is the cement content (Table 3).

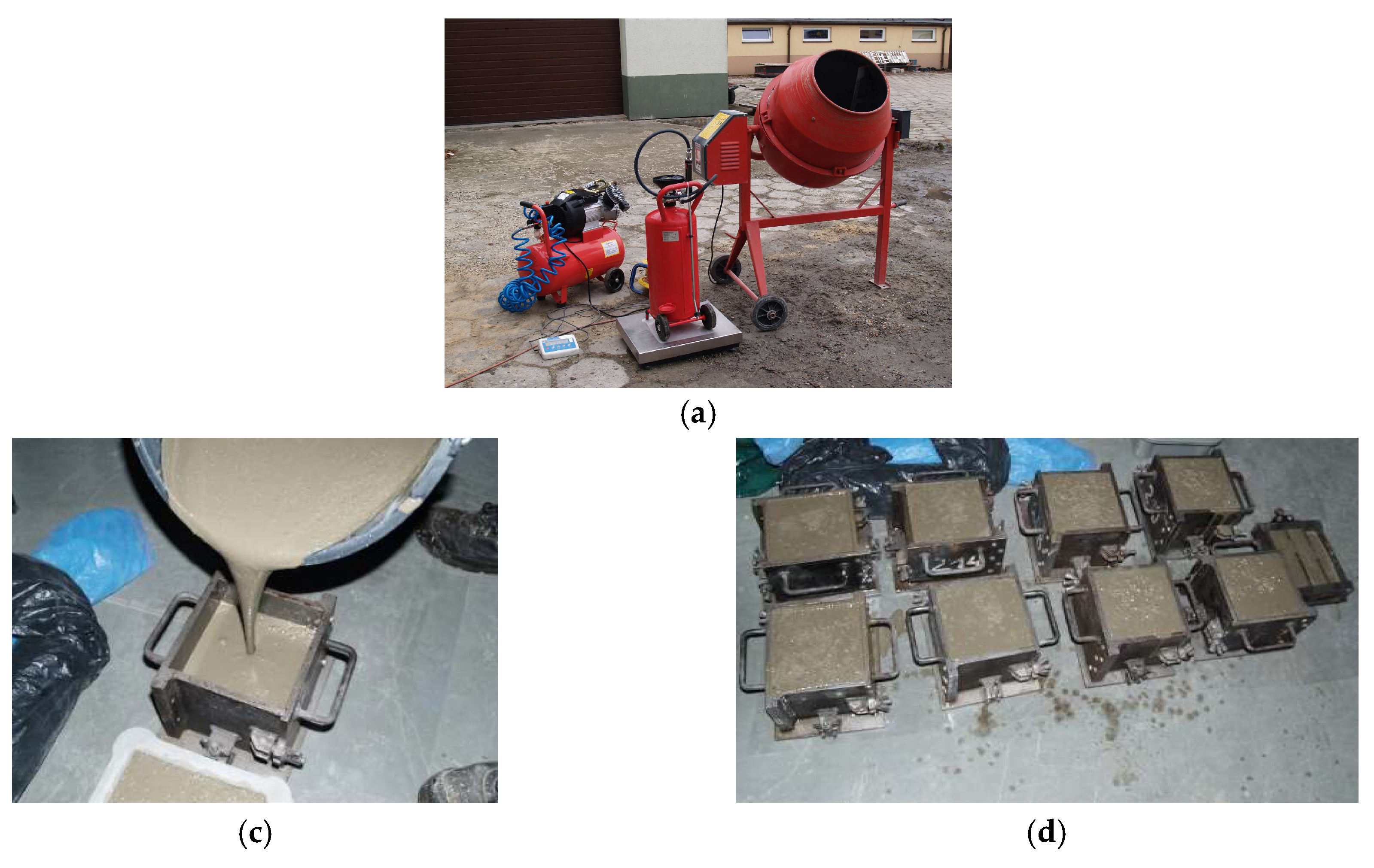

The foamed concrete specimens were prepared according to the pre-foaming method. At first, water and cement were mixed. Next, the foam was added and all components were mixed. In order to make a stable foam with density of 60±3 kg/m

3, the correct amount of liquid polymer agent was pressurized with air at approximately 5 bars using a foam generator (

Figure 1). The foam content was established on the basis of the target dry density of foamed concrete (considering earlier experiments, see

Table 1).

2.2. Specimen Preparation and Mix Composition and Production of Foamed Concrete Based on Protein Foaming Agent

The components of foamed concrete are cement, foaming agent, mixing water, aggregate, mineral additives and admixtures.

The materials used in this study were Portland cement, tap water, sand and protein foaming agent and admixture (superplasticizer recommended by the manufacturer – iwtech Ltd. Slovakia). The industrial Portland cement was CEM I 32.5R, according to EN 197-1:2011 [

72]. It was used commercial foaming agent on the basis of hydrolyzed proteins (iwtech Ltd., Slovakia).

Analogously as before, samples of foamed concrete with three different densities (600, 800 and 1000 kg/m

3 with a tolerance of ±50 kg/m

3, marked as FC600-P, FC800-P and FC1000-P respectively) were produced, see

Table 2.

The foamed concrete mixes were produced by using special mixing machines (

Figure 2). Foamed concrete was produced in two separate processes. At first, fresh mortar was prepared. In this purpose, components of mortar were mixed. The foam with density of 45-85 kg/m

3, was produced in a separate process. The foam is made from a concentrate of a protein foaming agent diluted in clean water in the amount of 2.0 - 4.5%. Next, the foam was added to fresh mortar and all ingredients were mixed at a constant rotational speed. In order to ensure the appropriate quality of foamed concrete, the machine was equipped with systems for automatic dosing of the foamed concrete mix components. The components were dozed by weight (

Figure 2).

2.3. Specimen Preparation

Samples were prepared in steel moulds (

Figure 1b,c) and then covered with foil to protect against water evaporation and to ensure the best bonding conditions. After period of 24 hours in curing room at the temperature of 20 ± 1° C for subsequently, all of the specimens were removed from the moulds and stored for a further 14 days at 20±1°C and 95% humidity. After this time, the foamed concrete samples were stored under ambient conditions (at 20 ± 1° C and 60 ± 10% humidity).

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. General Information

Laboratory tests on samples were carried out after 28 days of curing. The density, porosity, microstructure and compressive strength of the foamed concrete were tested. Due to the relatively short period since the dissemination of foamed concrete, there are no test standards in place in Poland or Slovakia [

74,

75]. Therefore, the test methods for concrete were adopted.

2.4.2. Density

According to the standard EN 12390-7:2019 [

76] the density of foamed concrete samples were measured on 150 mm standard cubes. The samples were examined in their natural state of humidity. Three measured samples for each mix were tested.

2.4.3. Porosity

The porosity of hardened samples of foamed concrete was measured as per PN-EN 1936:2010 [

77]. The three specimens for each mix were measured.

2.4.6. Microstructure

For the purpose of carrying out microstructural tests, smaller samples measuring approximately 20 mm x 20 mm x 10 mm were cut from the centre of the casted elements. These samples were subjected to a procedure of further preparation including drying and immersing in resin under vacuum. The entire grinding and polishing process was then carried out. A detailed description of the sample preparation method is described in an earlier publication [

78]. Microscopic examinations were carried out using a scanning microscope model Sigma 500 VP from ZEISS (Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany). BSD (backscattered electron detector) detector images were collected. Elemental composition analysis and elemental distribution maps were performed using an EDS detector model UltimMax 40 from Oxford Instruments (Oxford Instruments NanoAnalysis, High Wycombe, UK). Samples of the polished sections were sputtered with gold before SEM examinations.

2.4.4. Compressive Strength

Similar to density measurements, compressive strength was tested on 150×150×150 mm specimens according to EN 12390-3:2019 [

79] using a MEGA 6-3000-100 compression machine (FORM + TEST, Riedlingen, Germany) with a maximum load capacity of 3000 kN. The loading rate (0.10±0.05 MPa/s) was assumed according to PN-EN 679:2008 [

80]. Three samples for each mix were tested.

3. Results and Discussion

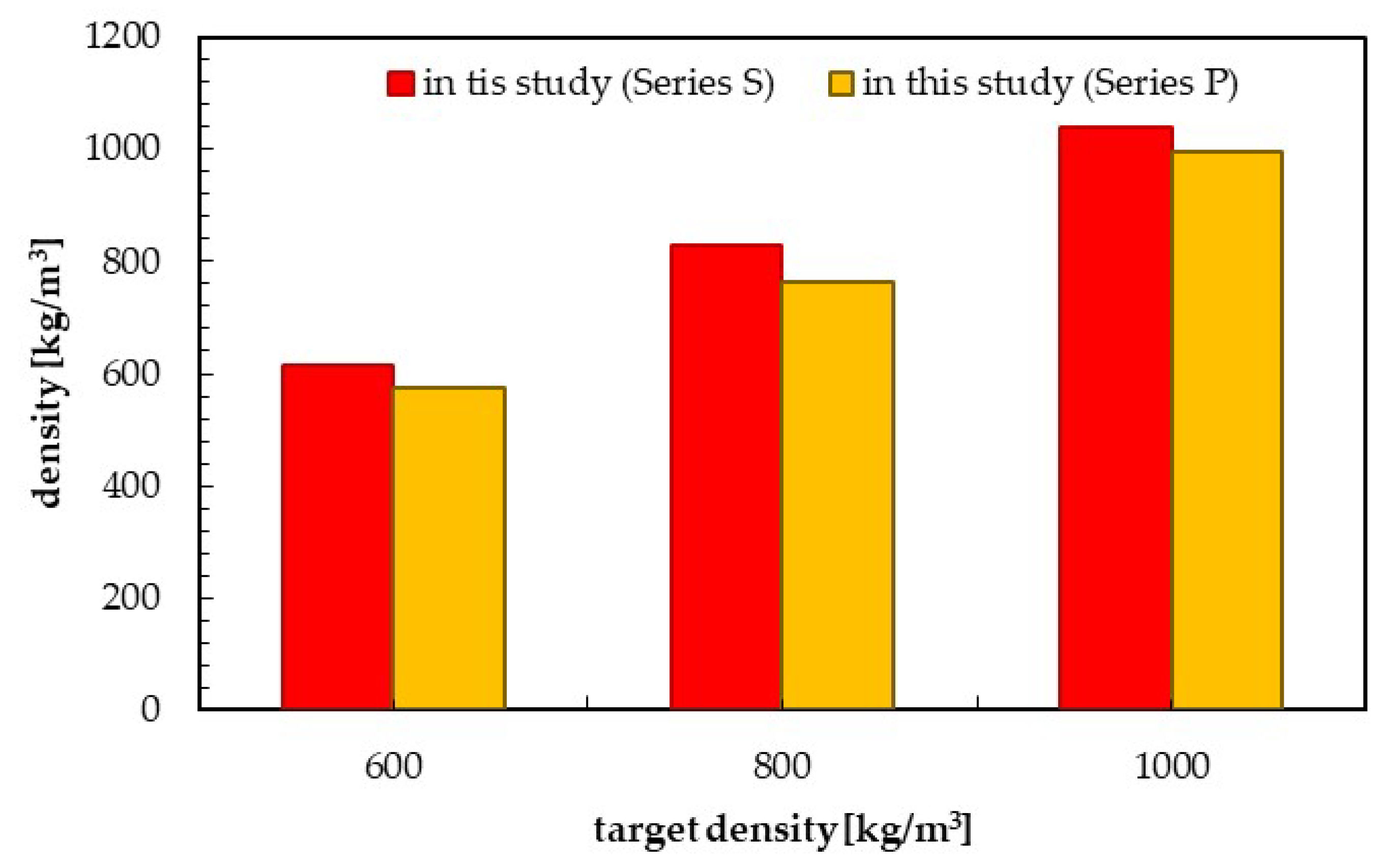

3.1. Density

Figure 3 presents the results of average densities of the hardened foamed concrete produced from different components. Samples produced from a foaming agent of synthetic origin are designated as Series S, and from a protein one - Series P. The difference between the assumed and obtained density is less than 50 kg/m

3 and less than 5%. This proves that the samples were manufactured correctly [

37].

It is interesting that for foamed concrete produced on the basis of a synthetic foaming agent, this difference increases with increasing density, while for a protein foaming agent it decreases (

Table 3). Observations in this direction should be conducted on a larger sample and are not the subject of this research.

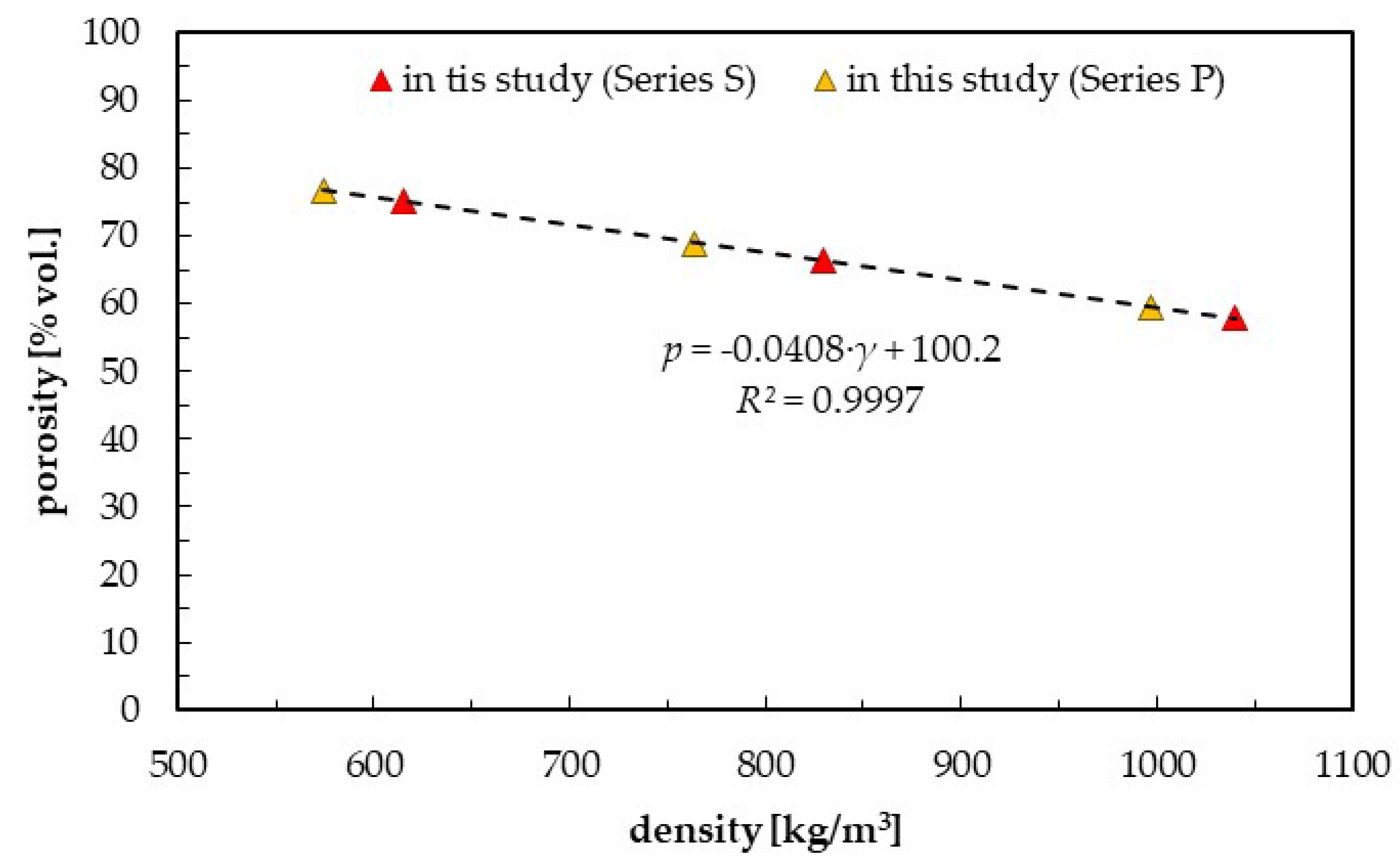

3.2. Porosity

According to the definition, foamed concrete contains more than 20% of the volume of air voids [

81]. For the analyzed samples, 80, 70 and 60% were obtained for foamed concrete with a density of 600, 800 and 1000 kg/m

3, regardless of the composition used, including the origin of the foaming agent. The porosity of foamed concrete decreased with increasing density. However, the obtained porosity values for foamed concrete produced with synthetic and protein foaming agent were very similar, see

Figure 4.

It can be seen that porosity results of foamed concrete were arranged along one line regardless of the type of foaming agent. The dashed line indicated the correlation between the density and porosity of foamed concrete for all results. This was a linear relationship, and Poisson’s ratio was close to 1, which indicated a high consistency of the results.

There are few results of foamed concrete porosity in the literature, and they are determined by different methods. Therefore, it is difficult to compare the obtained results with those of other scientists.

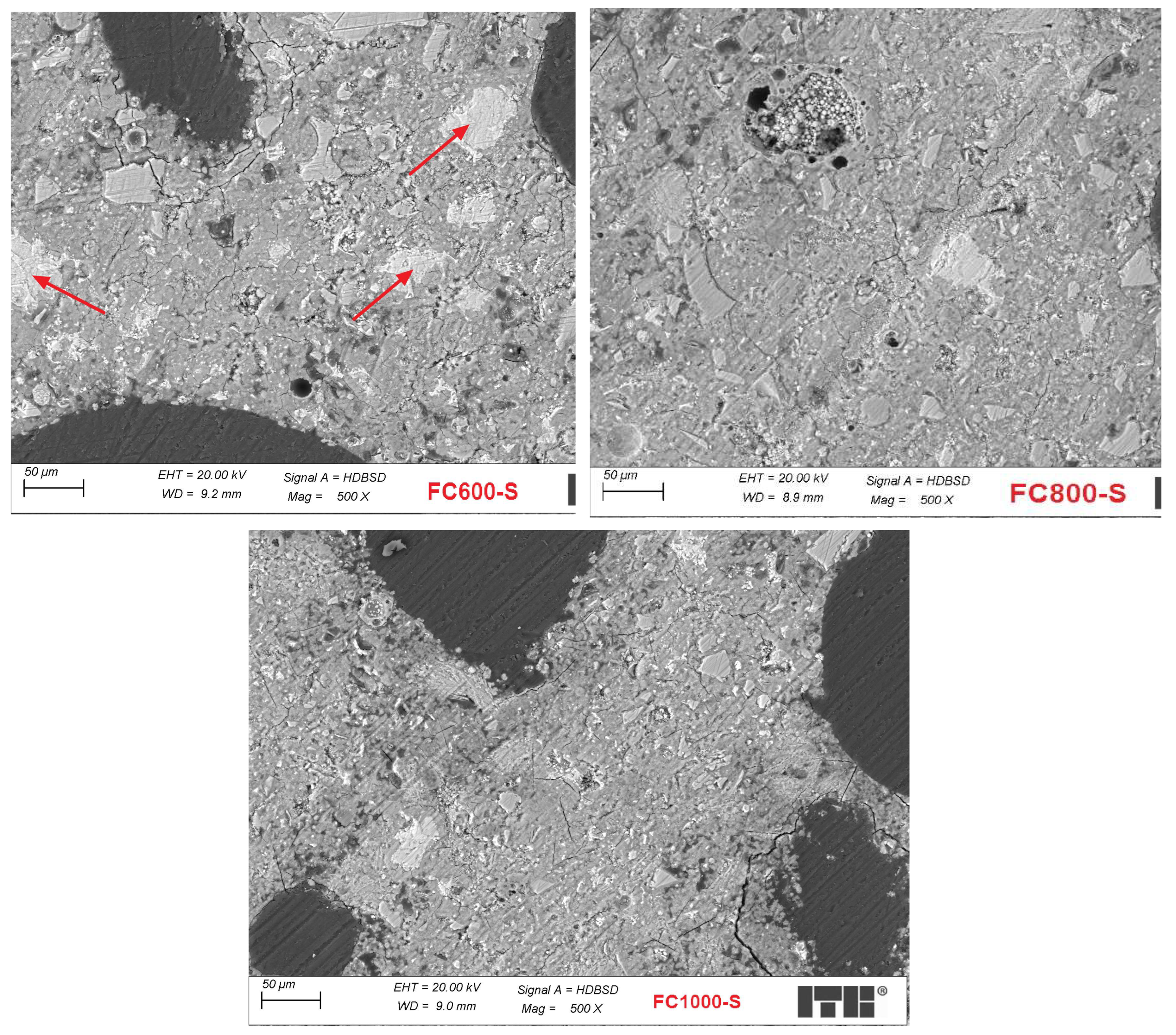

3.3. Microstructure

Figure 5 presents an example of microstructure of FC600-S, FC800-S and FC1000-S samples.

Analysis of microstructure of S-series foamed concrete have shown large amount of air voids, mainly macropores with diameter up to single millimetres. Most from the observed air voids were spherical with well-shaped edges. Some of observed cracks in microstructure were probably related with the sample preparation. With increasing density of foamed concrete number of air voids decreased. In cement grout several grains of clinker relicts were observed. Number of those grains seems to increase with the density of foamed concrete. C-S-H phase in most observed regions was seal and well developed without excessive porosity. Some grains of siliceous fly ash were observed but the quantity of fly ash seems to fulfil the requirements for the composition of CEM I cement (less than 5%).

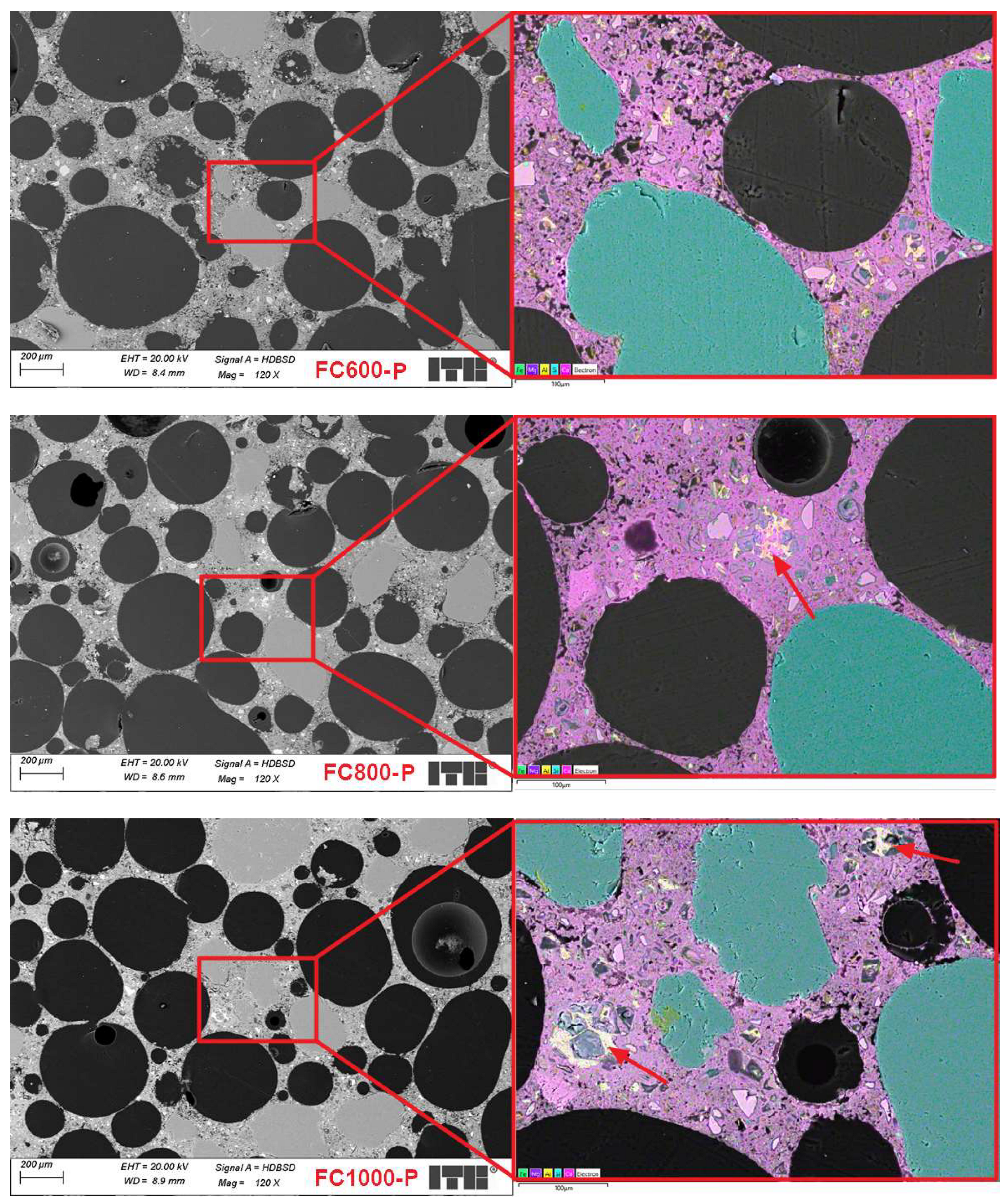

To compare the microstructure of foamed concretes produced with different types of foaming agents, the samples of P-series were also examined.

Figure 6 presents examples of microstructure of foamed concretes from P-series.

Microstructural analysis of the foamed concrete samples from P-series showed the presence of numerous air voids in all samples, mostly spherical with diameters ranging from tens of micrometres to a few millimetres. Number of air voids decreased during the increase of concretes density. The C-S-H phase was porous in most areas, only the areas surrounding the clinker relics were more compact and tight. Foamed concretes from P-series with higher density had their microstructure more seal and enriched with calcium, however it was still more porous than those observed in S-series. Diameters of cement clinker relicts were mostly larger than those observed in S-series. In concretes with higher density increase of content of fine, siliceous aggregates with diameter less than 0.5 mm were observed. Grains of fine aggregates were mostly well bounded to the cement matrix. Few grains of blast furnace slag with varying degrees of hydration were observed in the cement grout, but their number seems to fulfil the requirements for CEM I cement (less than 5%).

Comparison between microstructure of foamed concretes produced with different types of foaming agents relating to the similar densities have not shown significant differences with the number of air voids, their shape and distribution. C-S-H phase in P-series foamed concrete relating to the S-series was more porous and contained larger grains of clinker relict grains. Differences in grouts microstructure might be related with the higher water-cement ratio and lower content of cement in P-series. Larger grains of clinker are a consequence of lower specific surface area of cement 32.5 class relating to the 42.5 in S-series. Spotted differences in microstructure between both series of foamed concrete might be the cause of lower mechanical properties of P-series relating to the S-series.

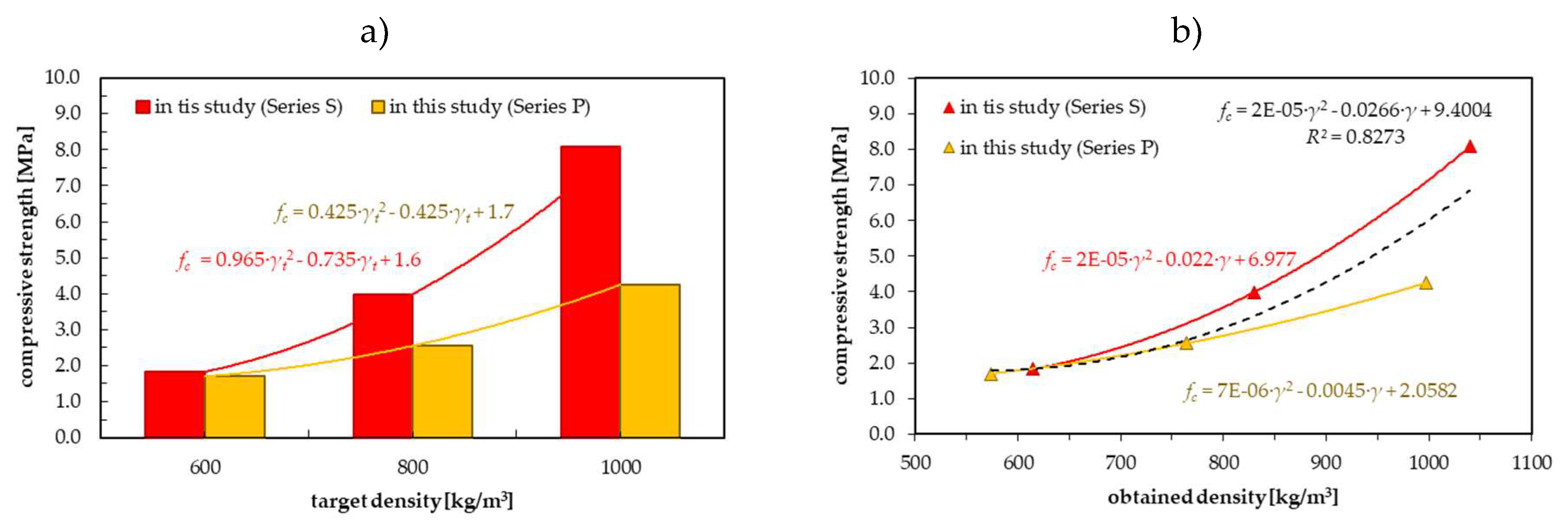

3.4. Compressive Strength

The results of compressive strength of foamed concrete for three assumed density was presented in

Figure 7a. It was observed that with increase in density, compressive strength also increased regardless of the origin of the foaming agent [

24,

56]. However, the compressive strength values are different. Therefore, compressive strength is directly related with density, what was found in previous studies [

53,

54,

55,

82] and by other scientists [

56], but this correlation is different for different compositions, including different types of foaming agent (

Figure 7b). The dashed line indicates the correlation made when all compressive strength results are relative regardless of the composition of the foamed concrete mix. The Poisson’s ratio is 0.91, which indicates a high degree of agreement between the fit.

The obtained results of compressive strength were consistent with the results of other scientists, e.g. Castillo-Lara et al. [

83] for foamed concrete with density of 706±8 kg/m

3 obtained 1.42±0.05 MPa. Conversely, She et al. [

52] for foamed concrete with 800 kg/m

3 obtained 3.61 MPa. From the referenced research results it can be observed that the obtained compressive strength values were higher for foamed concrete produced using synthetic foaming agent than protein foaming agent. For foamed concrete with a density of 600, 800 and 1000 kg/m3, the compressive strength was lower by about 10, 40 and 50%, respectively, for foamed concrete produced using an organic foaming agent. Similar results were obtained by Sun et al. [

42]. They demonstrated that approximately 43% and 11% higher compressive strength was obtained for foamed concrete based on a synthetic foaming agent compared to foamed concrete based on a natural foaming agent made from plant and animal protein (animal blood), respectively. This is due to the good structure of the foam (homogeneity of the bubbles) and its properties [

74]. Furthermore the synthetic foaming agent contains a stabiliser, such as nanoparticles, which may accumulate at the interface of the air bubbles [

52] to prevent collapsing. High stability and strength of the foam will be beneficial to maintaining the foam structure in the cement paste [

84], thus, resulting in higher compressive strength [

52].

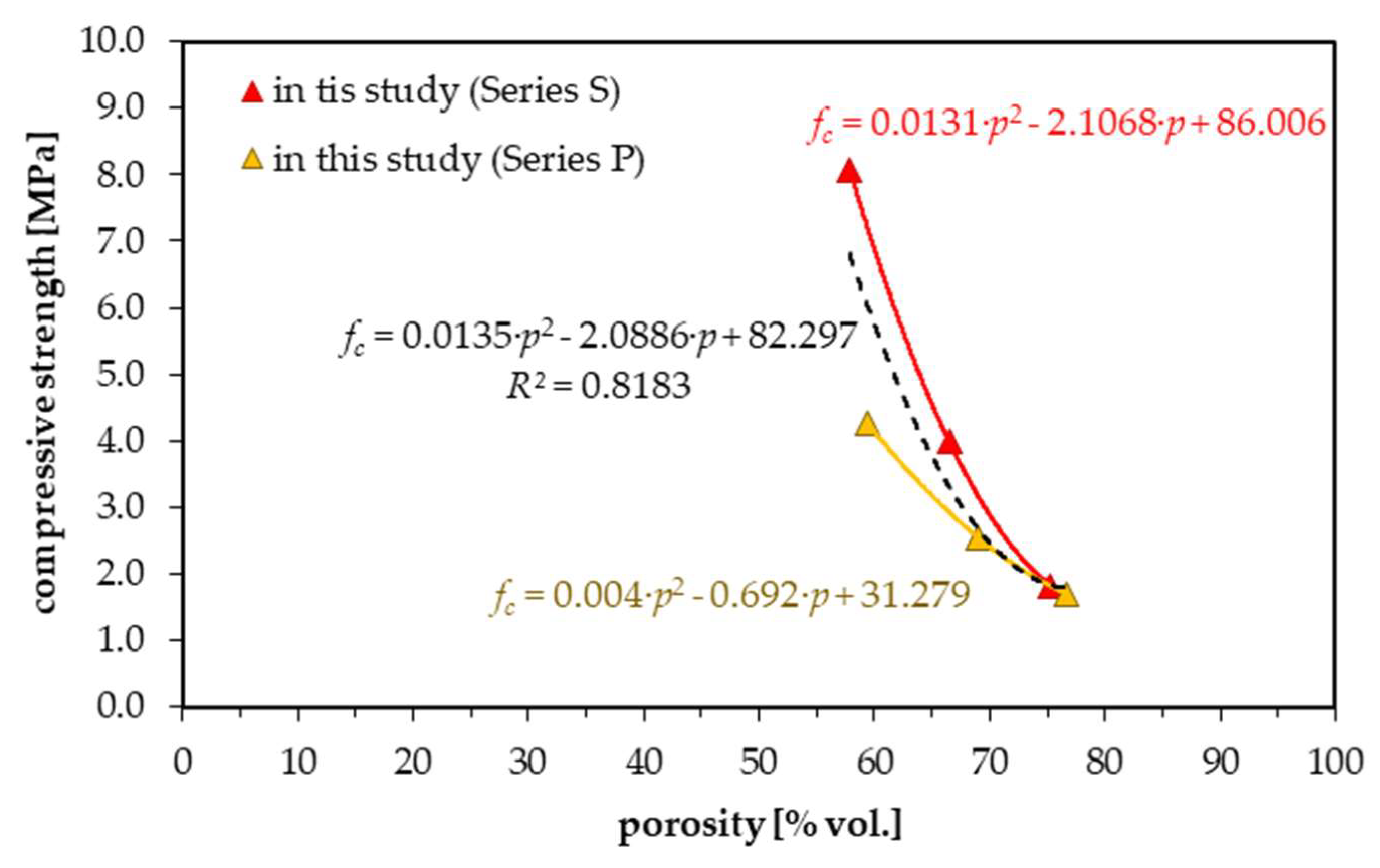

It is important, however, that the higher the density, the greater the difference between compressive strengths. Therefore, in the next step, the subject of analysis was the relationship between compressive strength and porosity. The results were shown in

Figure 8.

It can be observed that for the same porosity, the difference between the compressive strengths of foamed concrete made of different foaming agents is significant at lower porosity. At higher porosity (about 80%), the compressive strengths are comparable. Relating this to density, we have for higher density foamed concrete (800 and 1000 kg/m

3) with the same pore content (

Figure 8), higher compressive strengths were obtained for foamed concrete based on a synthetic foaming agent compared to foamed concrete based on a protein foaming agent. On the other hand, for lower density foamed concrete (600 kg/m

3) with the same pore content (

Figure 8), the compressive strengths are comparable (they do not depend on the composition and type of foaming agent). Thus, at higher densities of foamed concrete, its compressive strength is determined by the cement matrix, and at lower densities by the air void content. It should be noted here that these samples differed in the type of foaming agent but also in composition, particularly the cement used. In the first case, cement class CEM I 42.5R (FC-S samples) was used, in the second case cement class CEM I 32.5 (FC-P samples), which explains the significantly lower compressive strength obtained. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that directly illustrates the cause of the brittle behaviour of foamed concrete specimens with higher density, which has been described earlier and by other scientists, e.g. Castillo-Lara et al. [

53,

83].

5. Conclusions

The aim of the study was to assess the properties of foamed concrete made of a synthetic and protein foaming agent. Foamed concrete with a target density of 600, 800 and 1000 kg/m3 was analyzed. Based on the results of this experimental investigation, the following key conclusions can be drawn:

The density of hardened foamed concrete was obtained with a tolerance of ±50 kg/m3 and 5%.

The porosity was comparable for both foamed concretes, regardless of the type of foaming agent used. This indicates the possibility of obtaining the same microstructure and micro porosity regardless of the composition and origin of the foaming agent used.

The lower the density of foamed concrete, the higher the porosity. This relationship is linear.

Microstructure investigations of both series of foamed concretes have shown their similarity in air voids size, shape and distribution comparing the same density class. However the porosity of cement grout and C-S-H phase were different. In P-series the C-S-H phase was more porous, and cement paste contained larger grains of clinker relicts. Observed differences were caused mainly due to the lower content of cement, higher water-cement ratio and lower class of cement in P-series. Those differences might explain observed differences in mechanical properties between both series.

The differences between the compressive strengths of foamed concrete made of different foaming agents were significant at lower porosity. At higher porosity (about 80%), the compressive strengths were comparable.

For foamed concrete with higher density and with the same pore content, higher compressive strengths were obtained for foamed concrete based on a cement CEM I 42.5R and synthetic foaming agent compared to foamed concrete based on a cement CEM I 32.5 and protein foaming agent. For foamed concrete with lower density and with the same pore content, the compressive strengths are comparable (they do not depend on the composition and type of foaming agent).

For foamed concrete with higher densities, the compressive strength is determined by the cement matrix, and for foamed concrete with lower densities by the air void content. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study that directly illustrates such a statement.

In the analyzed case, the lower strength resulted from the lower strength of the cement matrix, because CEM I 32.5 cement was used to produce the FC-P samples, and CEM I 42.5R Portland cement was used to produce the FC-S samples. Also, FC-P samples had lower cement content and higher water-cement ratio what might be a cause of observed lower mechanical properties.

As part of future research, it is planned to develop a quantitative correlation between the class of cement used and the strength of foamed concrete with different air void contents. This will be particularly important when using low-emission cements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and M.D.; methodology, M.K, F.Ch., D.S. and A.K.; software, M.K.; validation, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K. and M.D.; investigation, M.K, F.Ch., D.S. and A.K.; resources, M.K. and M.D.; data curation, M.K., M.D. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., F.Ch. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and M.D.; visualization, M.K. and F.Ch.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results presented in this article are effects of the scientific internship at the Faculty of Civil Engineering at the University of Žilina, carried out within the Student and Academic Staff Exchange Program in Bilateral Cooperation – Outgoing Offer – Academic Year 2021/2022, financed by the NAWA (National Agency for Academic Exchange), agreement No. PPN/BIL/2020/1/00318/U/01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

SEM studies were carried out using a scanning electron microscope purchased from a special-purpose subsidy from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education for the implementation of an investment related to the scientific activities of the ITB (6967/IA/SN/2019) and the research project VEGA No. 1/0752/24 “Research of composite foamed concrete-based panels for applications in traffic construction”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zięba, Z., Dąbrowska, J., Marschalko, M., Pinto, J., Mrówczyńska, M., Leśniak, A., Petrovski, A., Kazak, J.K. Built environment challenges due to climate change. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth and Environ. Scie. 2020, 609, 012061. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C-L., Wang, Y., Qin, G., Zuo, P-B. Correction of the Temperature Effect of Muon Counts Observed at the Guangzhou Station. Res. Astron. Astroph. 2023, 23, 025010. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (CE). Closing the Loop - an EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. COM (2015) 614., Brussels, Belgium: 2015.

- Czarnecki, L.: Sustainable building products – beautiful idea, civilisation necessity or thermodynamic imperative. Mat. Bud. 2022, 1, 64-67. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-P., Cheng, X.-M. Energy consumption, carbon emissions, and economic growth in China. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68(10), 2706-2712. [CrossRef]

- Lapinskienė, G., Peleckis, K., Slavinskaite, N. Energy consumption, economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union countries. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18(6), 1082-1097. [CrossRef]

- Sterpu, M., Soava, G., Mehedintu, A. Impact of Economic Growth and Energy Consumption on Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Testing Environmental Curves Hypotheses on EU Countries. Sustain. 2018, 10, 3327. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (CE). Energy Roadmap 2050 Impact Assessment and Scenario Analysis. Brussels, Belgium: 2011. https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/roadmap2050_ia_20120430_ en_0.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Arouri, M.E.H., Youssef, A.B., M’henni, H., Rault, Ch. Energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions in Middle East and North African countries. Energy Pol. 2012, 45, 342-349. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector 2020.

- IEA. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2019, Paris:2019. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-status-report-for-buildings-and-construction-2019 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Zhong, X., Hu, M., Deetman, S., Steubing, B., Lin, H., Hernandez, G., Harpprecht, C., Zhang, C., Tukker, A., Behrens, P. Global greenhouse gas emissions from residental and commercial building materials and mitigation strategies to 2060. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6126. [CrossRef]

- Wall, S. CE Marking of Construction Products – Evolution of the European Approach to Harmonisation of Construction Products in the Light of Environmental, Sustainability Aspects. Sustain. 2021, 13(11), 6396. [CrossRef]

- Furtak, K. Contemporary challenges of science and technology – selected reflections. Cem. Lime Concr. 2021, 26(5), 413-430. [CrossRef]

- Heim, D. Isothermal storage of solar energy in building construction. Renew. En. 2010, 35(4), 788-796. [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejuk, H., Marks, W. Optimization of shape and functional structure of buildings as well as heat source utilization. Basic theory. Build. Environ. 2002, 37(12), 1379-1383. [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R., McCarthy, A. Preliminary views on the potential of foamed concrete as a structural material. Mag. Concr. Res.2005, 57(1), 21-31. [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, K., Nambiar, E.K., Ranjani, G.I.S. A classification of studies on properties of foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 388–396. [CrossRef]

- Dhir, R.K.; Newlands, M.D.; McCarthy A. Use of foamed concrete in construction. Proceedings of International Conference on the Use of Foamed Concrete in Construction. Dundee: University of Dundee, Scotland, 5 July 2005, London: Thomas Telford Ltd 2005.

- Hilal, A.A., Thom, N.H., Dawson, A.R. On entrained pore size distribution of foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 227–233. [CrossRef]

- Alonge, O.R., Mahyuddin, R. Experimental production of sustainable lightweight foamed concrete. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 994–1005. [CrossRef]

- Hajimohammadi, A., Ngo, T., Mendis, P. Enhancing the strength of pre-made foams for foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 87, 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Proshin A.P., et al. Unautoclaved foam concrete and its construction adapted to regional conditions, [in:] Dhir, R.K.; Newlands, M.D., McCarthy A. (eds.) Use of foamed concrete in construction. Proceedings of International Conference on the Use of Foamed Concrete in Construction. Dundee: University of Dundee, Scotland, 5 July 2005, London: Thomas Telford Ltd. 2005, pp. 113–120.

- Nambiar, E.K., Ramamurthy, K. Air-void characterization of foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Raj, A., Sathyan, D., Mini, K.M. Physical and functional characteristics of foam concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 221, 787–799. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Wang, X., Wang, L., Li, Y. Foam concrete: A state-of-the-art and state-of-the-practice review. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 6153602. [CrossRef]

- Silva N., et al. Foam concrete-aerogel composite for thermal insulation in lightweight sandwich facade elements, [in:] Concrete 2015: Proceedings of the 27th Biennial National Conference of the Concrete Institute of Australia in conjunction with the 69th RILEM Week “Construction Innovations, Research into Practice”, Institute of Australia, 30.08–02.09.2015, Melbourne, Australia, p. 1355-1362.

- Xianjun, T., Weizhong, C., Yingge, H., Xu, W. Experimental study of ultralight (<300 kg/m3) foamed concrete. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 514759. [CrossRef]

- Jones M.R., McCarthy A. (2005), Behaviour and assessment of foamed concrete for construction applications, [in:] Dhir R.K., Newlands M.D., McCarthy A. (eds.): Use of foamed concrete in construction. Proceedings of International Conference on the Use of Foamed Concrete in Construction. University of Dundee, Scotland, 5 July 2005, London: Thomas Telford Ltd. 2005, p. 61–88.

- Jones M.R., McCarthy A. Heat of hydration in foamed concrete: Effect of mix constituents and plastic density, Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36(6), 1032-1041. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Zahari, N., et al. Foamed concrete: potential application in thermal insulation, [in:] Proceedings of Malaysian Technical Universities Conference on Engineering and Technology (MUCEET), MS Garden, Kuantan, Pahang, Malaysia, 2009.

- She W., Zhang Y., Jones M.R. Three-dimensional numerical modeling and simulation of the thermal properties of foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 421–431. [CrossRef]

- Vinith Kumar, N., Arunkumar, C., Srinivasa Senthil, S. Experimental Study on Mechanical and Thermal Behavior of Foamed. Mater. Tod.: Proc. 2018, 5(2), Part 3, 8753-8760. [CrossRef]

- Shang X., Qu N., Li J. Development and Functional Characteristics of Novel Foam Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 324, 126666. [CrossRef]

- Park S.B., Yoon E.S., Lee B.I. (1999), Effects of processing and materials variations on mechanical properties of lightweight cement composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29(2), 193–200. [CrossRef]

- Giannakou, A., Jones M.R. (2002), Potential of foamed concrete to enhance the thermal performance of low-rise dwellings [in:] Innovations and Developments in Concrete Materials and Construction: Proceedings of the International Conference Held at the University of Dundee, Scotland, UK on 9–11 September 2002. London: Thomas Telford Publishing, 2002.

- Bindiganavile V., Hoseini M. Foamed concrete, [in:] Mindess S. (ed.): Developments in the formulation and reinforcement of concrete. 1st ed., Sawston: Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2008, pp. 231-255.

- Chen, B.; Liu, N. A novel lightweight concrete-fabrication and its thermal and mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 691-698. [CrossRef]

- Amran M.Y.H, et al. Design Efficiency, Characteristics, and Utilization of Reinforced Foamed Concrete: A Review. Crystals 2020, 10, 948. [CrossRef]

- Priyatham, B.P.R.V.S., Lakshmayya, M.T.S., Chaitanya, D.V.S.R.K. Review on performance and sustainability of foam concrete, Mater. Tod.: Proc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pokorska-Silva, I., Kadela, M., Fedorowicz, L. A reliable numerical model for assessing the thermal behavior of a dome building. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101706. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C., Zhu, Y., Guo, J., Zhang, Y., Sun, G. Effects of foaming agent type on the workability, drying shrinkage, frost resistance and pore distribution of foamed concrete, Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 186, 833-839. [CrossRef]

- Samson, G., A. Phelipot-Mardelé, and C. Lanos, Thermal and mechanical properties of gypsum-cement foam concrete: effects of surfactant. Europ. J. Environ. Civ. Eng.2017, 21(12), 1502-1521. [CrossRef]

- Behnia, S., et al., Nonlinear transitions of a spherical cavitation bubble. Chaos, Solit.&Fract. 2009, 41(2), 818-828. [CrossRef]

- https://www.izolacje.com.pl/artykul/sciany-stropy/182794,pianobeton-material-termoizolacyjny-czy-konstrukcyjny (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Mydin, M.A.O, Noordin, N.M. Mechanical, Thermal and Functional Properties of Green Lightweight Foamcrete. Anal. Univ. “Eftimie Murgu” J. 2012, 19(1), 153-164. https://anale-ing.uem.ro/2012/18.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Narayanan, N., Ramamurthy K. Structure and properties of aerated concrete; a review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 321-329. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.S., I.S.R. Gandhi, and S. Khwairakpam, State-of-the-Art Review on the Characteristics of Surfactants and Foam from Foam Concrete Perspective. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. A 2018, 99, 391–405. [CrossRef]

- Selija K., Gandhi I.S.R.: Comprehensive investigation into the effect of the newly developed natural foaming agents and water to solids ratio on foam concrete behaviour. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 58, 105042. [CrossRef]

- Izvolt, L.; Dobes, P.; Drusa, M.; Kadela, M.; Holesova, M. Experimental and Numerical Verification of the Railway Track Substructure with Innovative Thermal Insulation Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 160. [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; Rattanasak, U. Shrinkage behavior of structural foam lightweight concrete containing glycol compounds and fly ash. Mater. Design 2011, 32, 723-727. [CrossRef]

- She, W.; Du, Y.; Miao, Ch.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Application of organic- and nanoparticle-modified foams in foamed concrete: Reinforcement and stabilization mechanisms. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 106, 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Kadela, M.; Kukiełka, A. Fracture energy of foamed concrete based on three-point bending test on notched beams. Proc. Eng. 2015, 108, 349-354. [CrossRef]

- Kadela M., Kukiełka A., Małek M. (2020), Characteristics of lightweight concrete based on a synthetic polymer foaming agent, Materials, vol. 13, no. 21, 4979. [CrossRef]

- Kadela M., Kukiełka A.: Influence of foaming agent content in fresh concrete on elasticity modulus of hard foam concrete [in:] Brittle Matrix Composites 11 - Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Brittle Matrix Composites BMC 2015, Warsaw: WIL PW, 2015, 11, 489-496.

- Amran, Y.H.M., Farzadnia, N., Ali, A.A.A. Properties and applications of foamed concrete: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 990-1005. [CrossRef]

- Kearsley, E.P. Just foamed concrete – an overview. Specialist techniques and materials for construction [in:] Proceedings of the International Conference “Creating with Concrete”, Dundee: University of Dundee, 1999, pp. 8–10.

- Nambiar, E.K.K., Ramamurthy, K. Sorption characteristics of foam concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37(9), 1341-1347. [CrossRef]

- Panesar, D.K., Cellular concrete properties and the effect of synthetic and protein foaming agents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 44, 575-584. [CrossRef]

- Feneuil, B., et al. Stability criterion for fresh cement foams. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 125, 105865. [CrossRef]

- Amran, Y.H.M.; Rashid, R. S.M.; Hejazi, F.; Safiee, N.A; Ali, A.A.A. Response of precast foamed concrete sandwich panels to flexural loading. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 7, 143-158. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Lu, Z.; Niu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang Y. Study on the preparation and properties of high-porosity foamed concretes based on ordinary Portland cement. Mater. Design 2016, 92, 949-959. [CrossRef]

- Falliano, D.; De Domenico, D.; Ricciardi, G.; Gugliandolo, E. Experimental investigation on the compressive strength of foamed concrete: Effect of curing conditions, cement type, foaming agent and dry density. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 735-749. [CrossRef]

- Falliano, D., Restuccia, L., Gugliandolo, E. A simple optimized foam generator and a study on peculiar aspects concerning foams and foamed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 268, 121101. [CrossRef]

- Beningfield N., Gaimster R., Griffin P. Investigation into the air void characteristics of foamed concrete [in:] Dhir, R.K.; Newlands, M.D., McCarthy A. (eds.) Use of foamed concrete in construction. Proceedings of International Conference on the Use of Foamed Concrete in Construction. Dundee: University of Dundee, Scotland, 5 July 2005, London: Thomas Telford Ltd. 2005, pp. 51-60.

- ACI523.1R-06 Guide for Cast-in Place Low Density Cellular Concrete. ACI Committee 523.

- Tikalsky, P.J., Pospisil, J., MacDonald, W. A method for assessment of freeze-thaw resistance of preformed foam cellular concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 889-893. [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M. and M. Tantray. Comparative study on the performance of protein and synthetic-based foaming agents used in foamed concrete. Cas. Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 14, p. e00524. [CrossRef]

- Gołaszewski, J., Klemczak, B., Smolana, A., Gołaszewska, M., Cygan, G., Mankel, C., Peralta, I., Röser, F., Koenders, E.A.B. Effect of the type of foaming agent on the properties of ultra-low-density foam concrete. Mat. Bud. 2022, 7, 43-45. [CrossRef]

- Gołaszewski, J.; Klemczak, B.; Smolana, A.; Gołaszewska, M.; Cygan, G.; Mankel, C.; Peralta, I.; Röser, F.; Koenders, E.A.B. Effect of Foaming Agent, Binder and Density on the Compressive Strength and Thermal Conductivity of Ultra-Light Foam Concrete. Buildings 2022, 12, 1176. [CrossRef]

- Hou L., Li J., Lu Z., Niu Y. Influence of foaming agent on cement and foam concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122399. [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1:2011 Cement - Part 1: Composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- https://www.iwtecheurope.com/en (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Yu, W., Liang, X., Ni, F. M-W., Oyeyi, A. G., Tighe, S. Characteristics of Lightweight Cellular Concrete and Effects on Mechanical Properties. Materials 2020, 13(12), 2678. [CrossRef]

- Ni, F.M.-W., Oyeyi, A.G., Tighe, S. The potential use of lightweight cellular concrete in pavement application: a review. Intern. J. Pavem. Res. Technol.2020, 13, 686-696. [CrossRef]

- EN 12390-7:2019 Testing hardened concrete - Part 7: Density of hardened concrete. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- PN-EN 1936:2010 Natural stone test methods - Determination of real density and apparent density, and of total and open porosity. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2010.

- Chyliński, F. Microstructural Assessment of Pozzolanic Activity of Ilmenite Mud Waste Compared to Fly Ash in Cement Composites. Materials 2024, 17, 2483. [CrossRef]

- EN 12390-3:2019 Testing hardened concrete - Part 3: Compressive strength of test specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- PN-EN 679:2008 Determination of the compressive strength of autoclaved aerated concrete. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2008.

- Van Deijk, S. Foam concrete, Concr.1991, 25(5), 49–54.

- Kozłowski, M.; Kadela, M. Mechanical Characterization of Lightweight Foamed Concrete. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 6801258. [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Lara, J.F., et al. Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Reinforced Foamed Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 3060. [CrossRef]

- Gonzenbach, U.T.; Studart, A.R.; Tervoort, E.; Gauckler, L.J. Stabilization of foams with inorganic colloidal particles. Langmuir2006, 22(26), 10983–10988. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).