1. Introduction

Robotic mapping is a very active and vibrant research field in mobile robotics [

1]. Mapping plays a crucial role in autonomous robot navigation, providing a fundamental understanding of the robot’s environment. It involves creating a representation of the surroundings, which enables the robot to perceive and navigate its environment effectively. There are several key reasons why mapping is vital in autonomous robot navigation, such as -

Environment understanding: Mapping allows the robot to understand its surroundings comprehensively. The robot can identify obstacles, structures, and features within its environment using a map. This information is vital for the robot to plan its movements, avoid collisions, and make informed navigation decisions.

Path planning and optimization: The robot can plan optimal paths from its current location to the desired destination with an accurate map. The map provides valuable information about the environment’s layout, including distances, obstacles, and acces- sible areas. It enables the robot to choose efficient, obstacle-free paths, saving time and energy.

Obstacle avoidance: Mapping assists in obstacle avoidance by identifying potential hazards and obstacles in the robot’s path. A detailed map allows the robot to ana- lyze its planned trajectory and adjust to avoid collisions or navigate obstacles. This capability enhances the safety and reliability of the robot’s navigation.

Localization and positioning: Mapping is closely tied to localization, which determines the robot’s position within the environment. The robot can accurately estimate its location by comparing sensor readings with the known map. Localization is crucial for precise navigation, especially in complex and dynamic environments.

Overall, mapping is an important task for the autonomous navigation of all types of robots, including those used for farming operations. Navigation of ground-based mobile robots in outdoor farm environments generally uses four main types of route planning approaches: sampling-based planners, graph search-based planners, numerical optimization planners, and interpolating curve planners [

2]. Route planning can be deterministic, where the entire path is generated prior to navigation, or sensor-based, where the path is created using real-time sensor feedback. A global optimum can be found in deterministic planning, but the execution depends on the local sensor’s feedback information. Moreover, processing extensive data from sensors would require substantial computational power, limited to small mobile robots. Hence, creating a map before the intended operation is helpful for small robots to devise optimized routes rather than solely relying on local sensor feedback.

The natural outdoor agricultural environment is diverse, and the crop field environment is no exception. Moreover, the agricultural field environment is more complex than a conventional city or urban environment. Row planting is a widespread practice in farming systems. Precision agriculture has flourished through row plantation in recent years to maximize crop production and cost-effectiveness by using different sensors, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) [

3,

4,

5]. The field environment of row crops such as corn, soybean, wheat, or sorghum is complex for autonomous robots traveling through rows. Finding optimum route planning is challenging, including non-deterministic polynomial-time (NP-hard) problems, among others [

6]. Hence, aerial map creation of a particular crop field before any robotic operations would help to assess the field conditions and optimize operations in accordance with the capability of ground robots before starting the operation by ground robots.

Drones are Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), which have received special attention in recent years as a low-cost platform for carrying imaging sensors during the last two decades [

7,

8]. UAVs can gather images in visible, infrared, and thermal regions of the electromagnetic field with very high spatio-temporal resolution [

9]. It is imperative to implement autonomous methods for extracting features from UAV images efficiently and affordably to meet the increasing need for sustainable and precision agriculture (PA) [

10]. Detecting crop rows in UAV images and subsequent automated extraction is crucial for crop management, including rectifying sowing errors, monitoring growth stages, counting seedlings, estimating yields, and facilitating crop harvesting [

11]. Various approaches have been previously employed to identify and extract crop rows from UAV images. The majority of these approaches involve image processing, where RGB or multispectral images are converted into binary representations of vegetation and non-vegetation using color indices and segmentation techniques such as supervised and unsupervised clustering [

12,

13] or image transformation techniques [

7]. Many studies used the Hough transform and its different variations [

11,

14,

15]. Some studies used Fast Fourier transform (FFT) [

16,

17]. Recently, convolutional neural networks (CNN) have also shown promising results [

18,

19,

20].

Drones have one particular advantage: they can be operated high from the ground, allowing them to have a large vision area, and that area can be varied by varying its height while taking pictures. Those are more convenient for gathering data than custom satellite imagery of a particular crop field, and they can collect images multiple times as needed to keep pace with the development of crops’ growth. Cropping operations like weeding, watering, or spraying are performed at different times/stages of crop growth and need different maps for the intended operations. For example, weeding requires a map of weeds that are overgrown in inter-row or intra-row areas of the crop and vary from time to time. When weeds are overgrown to a certain level, it will warrant site-specific weeding; before weeding, a map would be helpful for the operation.

This paper shows a simple way of creating maps for row crop navigation of Unmanned Ground Vehicles (UGV) for agricultural operations using some standard tools. The created map could be used to optimize route plans, calculate robot energy budget, and plan farming operations such as weeding, spraying, etc. A methodology has been proposed to use the created map for autonomous navigation. Moreover, this method has the potential to be integrated with precision agricultural operations such as site-specific application of fertilizer or pesticide by using small robots.

1.1. Mapping For Robots

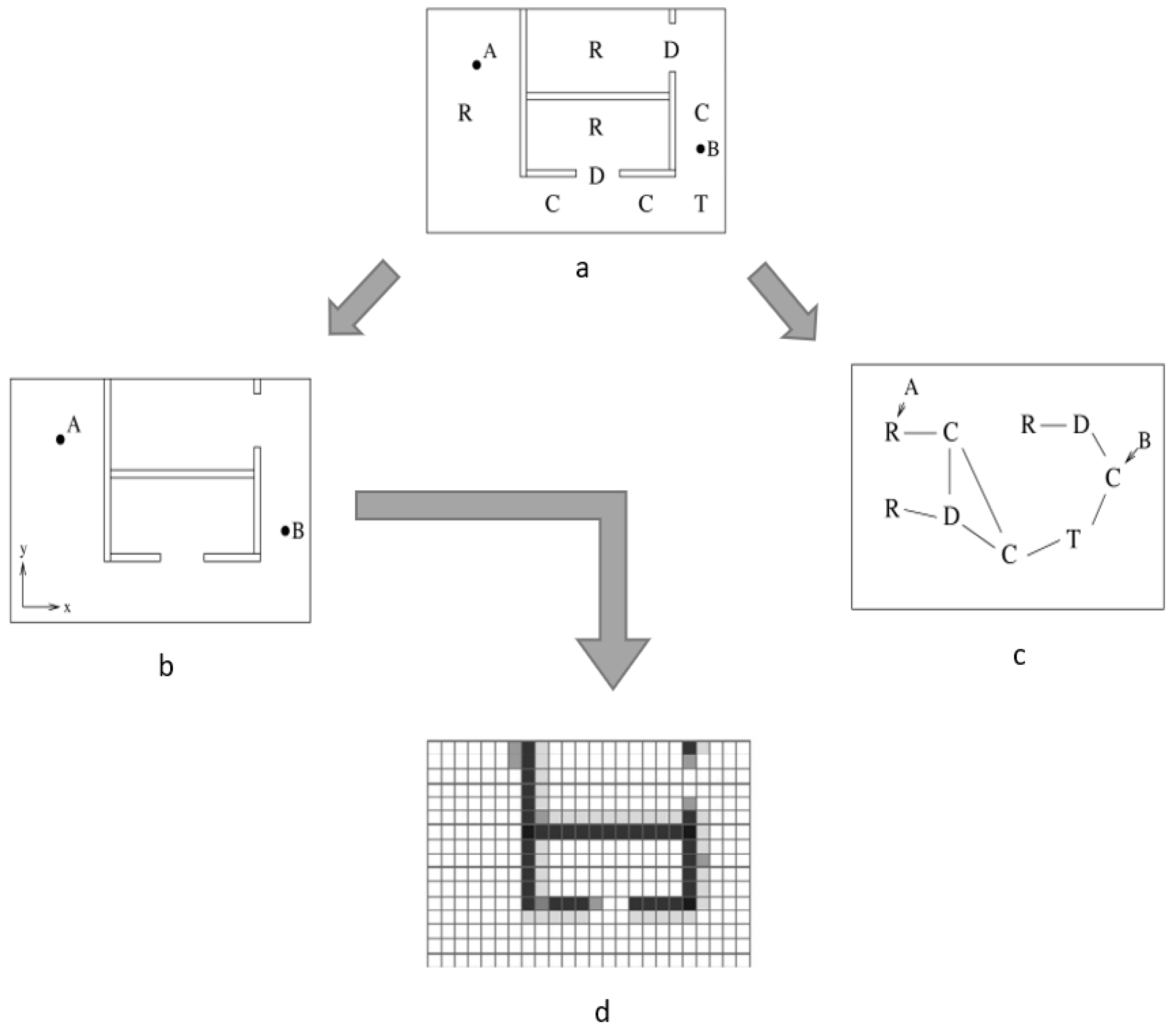

According to IEEE standards [

21] for 2D map representation for mobile robots, there are two main types of maps, namely metric maps and topological maps. A metric map is a type of map that represents the environment in a way that allows the robot to measure distances and locations accurately. It provides a geometric representation of the environment and is typically used for path planning, localization, and obstacle avoidance in mobile robotics. Metric maps provide a geometric representation of the environment, including the positions and shapes of obstacles, walls, landmarks, and other relevant features. This representation is often in terms of coordinates (e.g., x, y, and sometimes z) that allow the robot to measure distances and angles accurately. It is the most common type of map we are familiar with daily, like city maps or maps of a specific area.

Topological map representations can be thought of as structures rooted in graphs, where separate locations act as nodes linked by edges that specify viable routes for traversal. Unique places refer to positions in the environment characterized by sufficient distinctive features, making it relatively simple to determine their precise location. The typical approaches for creating topological maps often stem from using Voronoi diagrams. Topological maps are structurally correct but do not give an idea of whether a path is blocked or occupied.

Occupancy grid is one of the most crucial mapping methods for environmental modeling in mobile robotics [

23]. Occupancy grids portray the environment using gridded cells in two dimensions or voxel-based cells in three dimensions. It is a discrete representation where each cell is assigned a binary or probabilistic value to indicate its occupancy status. A binary occupancy grid uses a simple binary representation (1 for occupied and 0 for unoccupied). In contrast, a probabilistic grid assigns a probability value to each cell, indicating the likelihood of it being occupied or unoccupied. For probabilistic occupancy grid cells, assigned values indicate the confidence level in whether they are occupied or unoccupied. The probabilistic map operates under the usual assumption that the grid cells are unrelated. Occupancy grid maps are beneficial for different kinds of mobile robotic applications as they facilitate localization, path planning, navigation, and obstacle avoidance [

1,

24,

25]. Occupancy maps can be built using laser range finders [

26], sonar sensors [

27,

28] and stereo vision [

29].

Figure 1 shows a representation of these commonly used 2D maps.

For mobile robotics, usually, maps are generated using either SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) or a prebuilt map is loaded into the robot beforehand for autonomous navigation through an environment. SLAM is very useful for any autonomous navigation and is especially suitable for navigation in dynamic environments such as city traffic, supermarkets, or hospitals where humans, pets, and cars move alongside robots and in areas where no GPS signals or signals are obstructed. In addition to that, in city areas, there is a wide range of moving objects like cars, bicycles, trams with varying speeds, or stationary objects like road dividers, road barricades, etc. Therefore, a prebuilt map is not suitable in dynamic environment.In contrast, in agricultural scenarios such as in crop fields or greenhouses, there are very few moving objects compared to city areas; therefore, a prebuilt map is more suitable than a dynamic mapping method like SLAM. Moreover, prebuilt maps are helpful for energy budget calculation for small agricultural robots and optimize route planning to perform specific tasks like crop scouting.

SLAM is suitable for dynamic environment but has one important disadvantage: it is generally reliable in local regions but accumulates errors when mapping larger regions [

30]. Although there are some methods to avoid this error, such as feature matching, sensor scan matching, etc., mapping over a large area is not error-proof. Hence, SLAM is not a good option for mapping vast expansion of crop fields and pre-built map is more beneficial.

1.2. Related Work

Thinking of UGV and UAV integration in various tasks is not new and has been described by several studies [

31,

32]. The authors mentioned a framework for collaborative work between ground and aerial autonomous vehicles in the agriculture 4.0 scenarios with its pros and cons [

33]. UAVs have been used to create a map of obstacles and reconstruct the ground map for UGV navigation using the traditional A* algorithm [

34]. Some authors used UAVs to create maps using various image processing methods and developed a custom path-planning algorithm for UGV navigation [

35]. Different procedures have been used to create maps from UAV images that depend on the target type and environment [

7,

35]. There is one important study related to mapping for agricultural purposes in which the authors used UAV for route mapping of orchards [

36]. Some have used UAVs to detect crop rows [

7]. However, no studies have been found so far by the best knowledge of authors that propose UAV-generated maps for crop row navigation by UGV.

2. Methodology

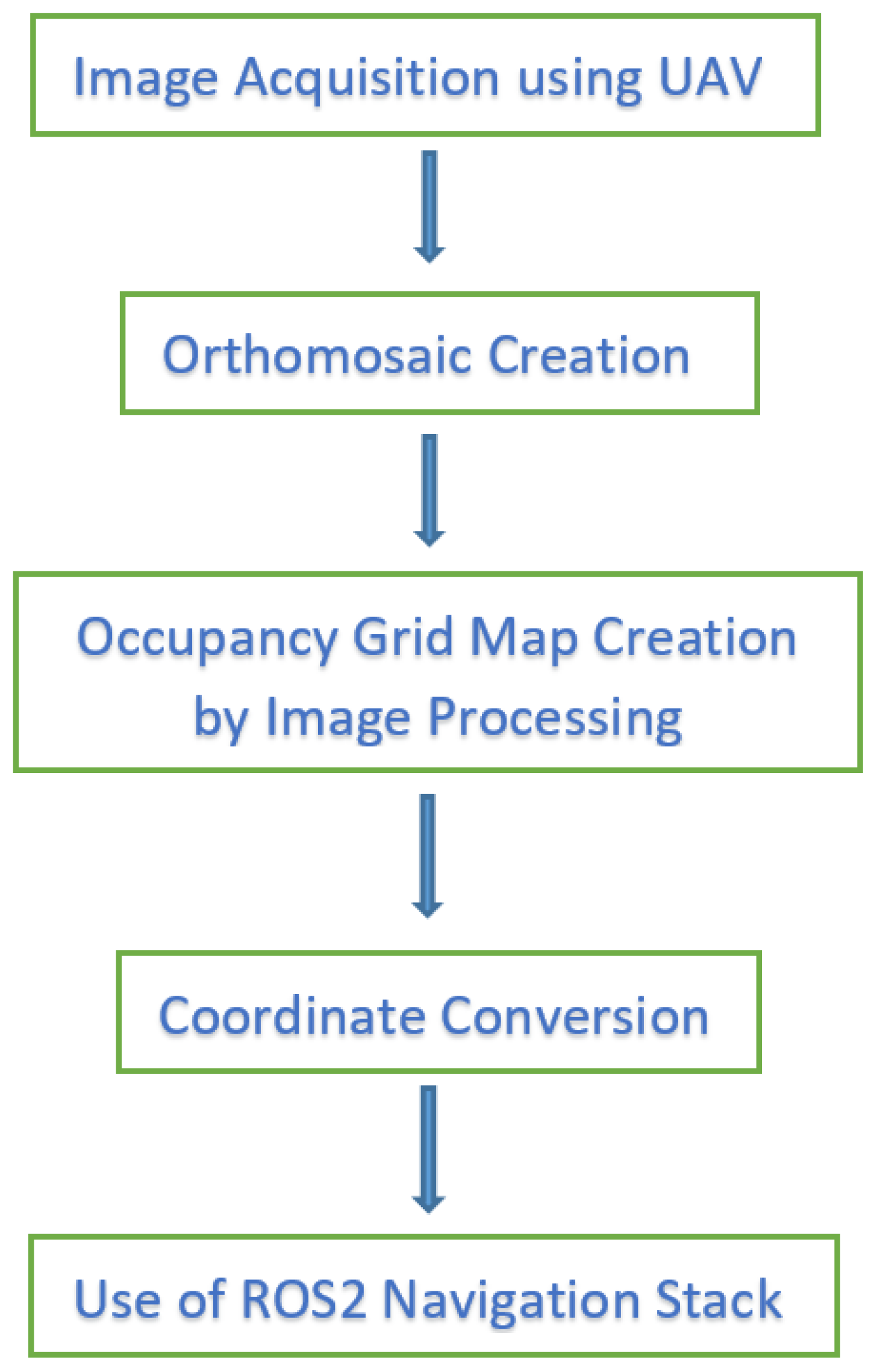

Our methodology for creating and using the map for navigation consists of five steps. A block diagram of those steps is shown in

Figure 2, and details of the each steps are given in the following sections -

Step 1: Image acquisition using UAV

UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) or drones would fly over the crop field through which the robot will perform its intended operation, such as scouting, spraying, or weeding. The flight plan would cover the whole area of the crop field. Mission planning of the UAV could be done using an open-source mission planner like Mission Planner or QGroundControl. Flight parameters like altitude, overlapping of the images, interval of taking pictures, etc., will be selected using the mission planner.

Step 2: Generation of orthomosaic image

Orthomosaic images are typically created by stitching together multiple individual images, such as aerial or satellite images, to create a seamless, orthorectified representation of a larger area. Orthorectification involves correcting the image for distortions caused by terrain variation and sensor characteristics, ensuring that the resulting image has a consistent scale and orientation. Orthomoasic images are essential for accurately measuring areas because images are corrected for perspective views, camera angles, and lens distortion, usually present in images taken using UAVs. Open-source orthomosaic image generation software WebODM or Agisoft (paid) would create an orthomosaic image of the crop field from a series of overlapped images.

Step 3: Generation of occupancy grid map

An occupancy grid map would be created for autonomous robot navigation through crop rows that divide the robot’s operating environment into a grid of cells. Each cell of the grid represents a specific area or region of the environment, and its occupancy status indicates whether the corresponding region is occupied by an obstacle (like a pivot rut or big stone) or is free space to move. To create an occupancy grid map, image processing techniques should be used to convert RGB or multispectral images into binary images where vegetative and non-vegetative areas are separated through some established methods to create an occupancy grid map (binary map) from images. The binary map is then converted to .pgm format, which is used in the Robot Operating System (ROS) for storing occupancy grid maps.

Step 4: Conversion of coordinates

After map generation, it is important to convert the GPS coordinates to actual distance because it is required to measure the traversable path for the robot. GPS coordinates, usually given in latitude/longitude format, need to be converted to cartesian coordinates by the UTM coordinate conversion method. UTM stands for Universal Transverse Mercator, a global coordinate system used to represent locations on the earth’s surface. It is based on a two-dimensional cartesian coordinate system, which makes it easier to perform accurate distance and angle calculations for relatively small areas on the ground. As the generated map is for ground robot navigation, it is very convenient to use UTM coordinates. UTM coordinates are widely used in cartography, surveying, and navigation. It divides the earth’s surface into multiple zones, each spanning 6 degrees longitude. The zones are numbered from 1 to 60, starting at the international date line in the Pacific Ocean and moving eastward. The UTM coordinate system utilizes eastings (measured along the east-west direction) and northings (measured along the north-south direction) to represent a location within a specific zone.

Step 5: Use of Nav2 framework of ROS

The generated occupancy grid map in .pgm (Portable Gray Map) format created earlier is fed to Navigation 2 or Nav2 framework [

37]. It is a powerful and flexible navigation stack designed to facilitate autonomous navigation for mobile robots. Nav2 framework is an evolution of the original ROS navigation stack, designed to provide more flexibility, modularity, and robustness for autonomous robot navigation [

38]. Nav2 is built on top of ROS2, the newer and more capable version of ROS, which addresses some of the limitations of ROS1 and adds support for real-time and distributed systems. Nav2 offers improved modularity, making it easier to customize navigation components based on specific robot platforms and environment requirements. It also supports a broader range of sensor inputs such as LiDAR, RADAR, sonar, depth images, etc., making it more adaptable to robotic systems. It uses modern techniques like Adaptive Monte Carlo localization (AMCL) based on particle filter for localization in a static map. It has another important feature - behavior trees (BT), which can be conveniently used for complex decision-making processes for multi-mobile robots [

39]. Behavior trees are better and more convenient than finite state machines (FSM) for decision-making in complex scenarios [

40]. To complete the navigable area’s coverage, open navigation’s “Nav2 Complete Coverage”. package of Nav2 could be used. This package is an extension of the “Fields2Cover” package [

41], which is a package for coverage path planning (CPP) problems. CPP is especially important for autonomous agricultural vehicles.

3. A Case Study

A small case study was conducted to test the validity of our method. Two popular row crops at two different locations were picked up for the study: one is corn, and another is soybean.

Location 1:

This study was conducted on four-acre corn fields at the Kansas Research Valley experiment field, Silver Lake, Kansas, USA, during 2020 and 2021. The experiment field had Eudora Silt Loam soil type. The growth stage was V12 and row spacing was 30 inches. Corn was planted in a row direction from west to east.

Location 2:

This study was conducted on seventeen-acre soybean fields at the Clay Center, Kansas, USA, during summer 2022. The experiment field had Silt Loam soil type. The growth stage was R4 and row spacing was 30 inches. Soybeans were planted in a row direction from south to north.

3.1. Map Creation

The navigational map creation process consists of two parts: orthomosaic image creation from a series of drone images and occupancy grid creation from that created orthomosaic image. The description of the two processes is as follows -

3.1.1. Orthomosaic Image Creation

A quadcopter, Matrice 100 (Shenzhen DJI Sciences and Technologies Ltd.), was used to collect aerial imagery. It has a payload capacity of 1 kg with a maximum flight time of 40 minutes. RGB (red, green, and blue) or true color images were collected using a Sony Alpha 5100, which has a CMOS sensor with an effective pixel density of 24 megapixels. For taking photographs, the UAV was flown at 50 m altitude with a speed of 3 m/s, which provided a ground sampling distance of 1.5 cm/pixel. Multiple flights were conducted throughout the study, but only flights representing the clear sky days and good-quality images were considered for analysis.

The UAV was flown on autopilot mode guided by a fixed route of waypoints, commonly known as a flight mission, generated using the mission planner. Forward and side overlaps between images were kept at 85 percent to meet image stitching requirements and smoothly develop orthomosaics. As recommended by the mission planner, the camera was triggered after 1 second depending on flying altitude and image overlap. Since the UAV was not directly compatible with the mission planner, a web-based platform (Litchi, VC Technology Ltd) was used to transfer missions from the mission planner to the UAV. Images were geotagged using the integrated module within the camera. Flights were conducted around solar noon since shadows on the side of plants before and after solar noon can cause errors in imagery. Captured images were stitched into orthomosaics following standard workflow from Metashape Professional by Agisoft (Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia). Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) corrected GPS coordinates of 16 ground control points (GCPs), distributed evenly throughout the field, were measured using Topcon GR-5 (Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) GNSS receivers with centimeter-level positioning accuracy. These coordinates were then used in Agisoft to provide images and orthomosaics with very high positioning accuracy. Before generating orthomosaics, images were calibrated to account for lighting conditions during the acquisition period. For this calibration, images taken before and after the UAV flight of a calibration panel (provided by the camera manufacturer) were used in Agisoft. For each flight date, the final product used from Agisoft was multispectral orthomosaics with cm-level positioning accuracy. Any raster-based mathematical operations were performed using the Raster calculator tool of ArcMap 10.6.1 (ArcGIS, ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA).

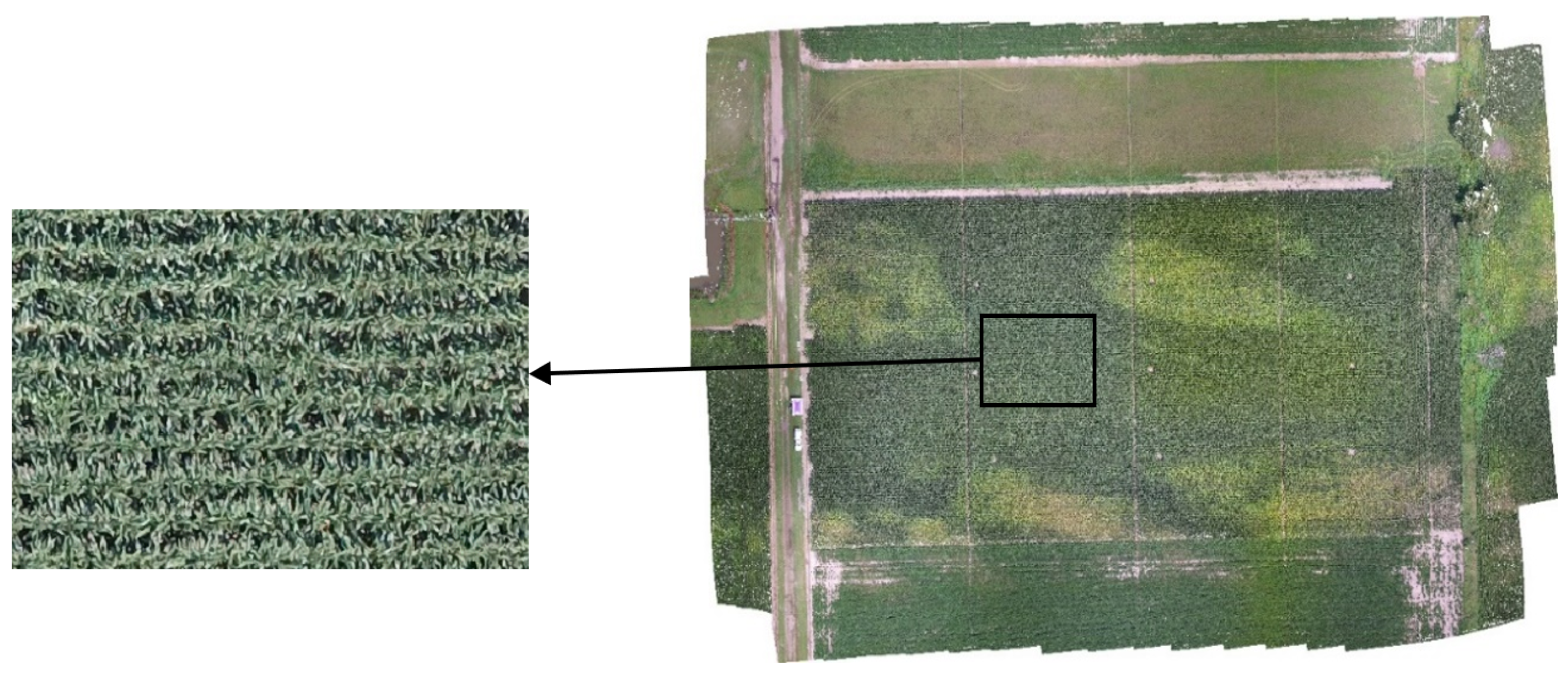

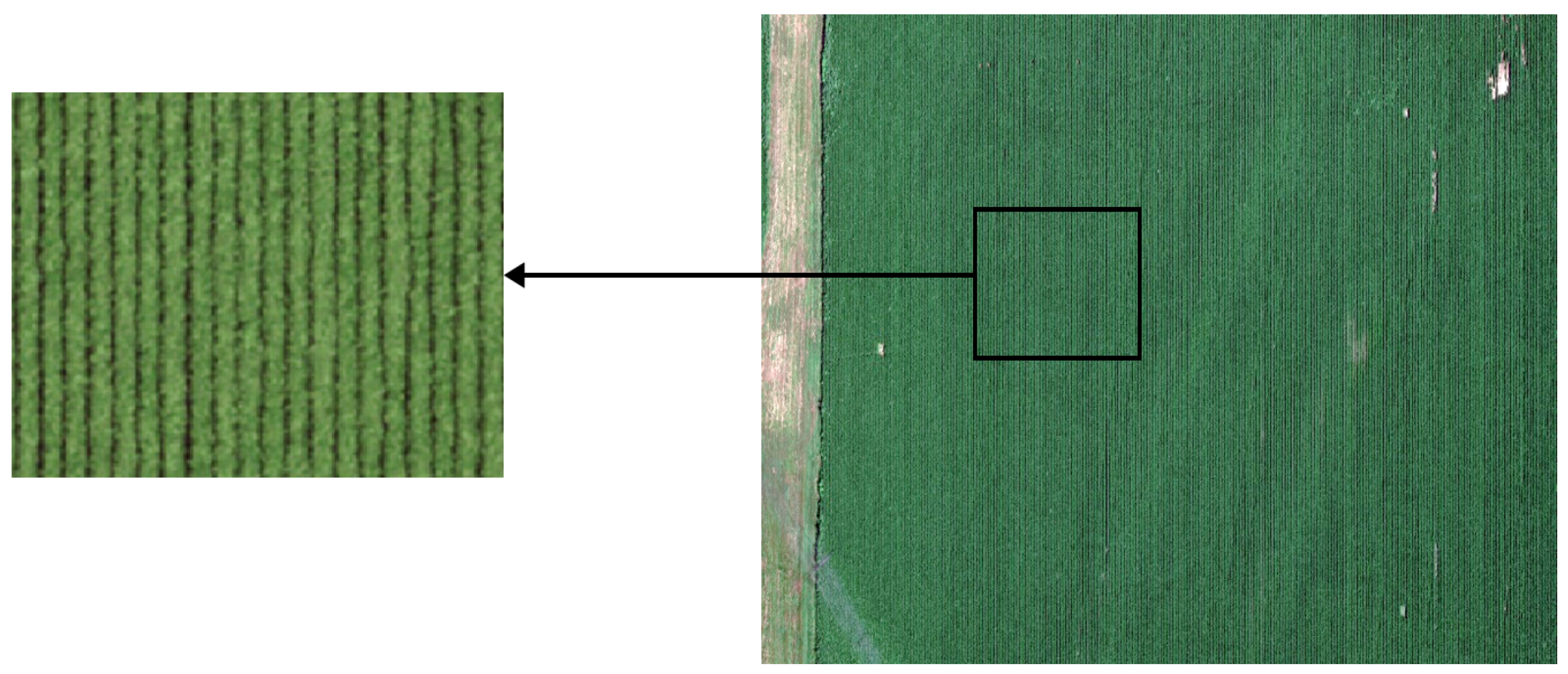

The created orthomosaic images of the corn and soybean field and zoomed-in view of the associated rows are shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively. The figures show that the canopy is very dense, and the leaves of plants between adjacent rows heavily cover the inter-row spaces with random patterns, as in the case of corn. In contrast, the soybean’s canopy is not dense like corn, and inter-row space is discernible with much better clarity than the corn field.

3.1.2. Occupancy Grid Creation

Image processing was used to create a binary map that can be used as an occupancy grid map for the autonomous navigation of robots. The image segmenter app of Matlab R2023a was used to do all the processing tasks. The following image processing operations (with default options) were used to extract the crop rows –

Two thresholding (global and adaptive) operations.

Morphological operations (dilation, erosion, opening, and closing) with different structuring elements (disc, diamond, and square).

After thresholding and converting to binary images with the app, the RGB images turn into images that could be used as occupancy grid maps that can be fed into the ROS navigation stack for the robot’s autonomous navigation.

4. Results And Discussion

The segmentation method shows promising results for soybeans when the crop rows are visibly well-defined with no significant overlap, as shown in

Figure 5. However, in the case of corn, when leaves overlap most of the rows, segmentation fails to efficiently differentiate rows (see

Figure 6) unlike soybeans. The two figures also show that global thresholding yields better result than the adaptive threshold in soybeans, whereas the adaptive threshold shows a slightly better result than the global threshold in corn. After segmentation, morphological operations (dilation, erosion, opening, and closing) with different structuring elements (disc, diamond, and square) were applied but the processes did not significantly improve the segmentation results and not worthy to mention.

The reasons behind the output differences in global and adaptive thresholding lie in the fact that global thresholding sets the threshold value based on the histogram of the entire image’s pixel intensity distribution. In contrast, adaptive thresholding calculates a threshold value for each small image region, allowing each region to have a distinct threshold value. Therefore, when a row is distinctive, global thresholding shows promising results. When a row is not distinguishable, adaptive thresholding shows better results as the threshold value is calculated based on local intensity variations.

This proposed method shows the feasibility of extracting crop rows for mapping purposes except in the case when the crop canopy covers most inter-row spaces. In the scenarios of complete coverage, conventional segmentation algorithms are insufficient to extract the navigable spaces. However, when the canopy doesn’t cover the inter-row spaces, this simple method works well, as shown in the case of soybeans. Although this method has not been tested in the early stages of crops, it is logical to assume that the process will yield better results when crops are in the early stages of development. It is expected that the very early emerging stage might not be optimum because, at this stage, the physical shape of crops changes too rapidly, and canopy coverage changes accordingly, ultimately dictating the interrow distances. The optimum picture-taking time mainly depends on the intended purposes (e.g., weeding, spraying) and the duration of the map usage by robots. When there is a significant change in the physical size of crops, it is always better to update the map just before the robot’s operation.

5. Use Of The Generated Map

The generated map can be used for different robotic operation tasks like -

Coverage path planning (CPP): Coverage path planning, or CPP is a crucial aspect of autonomous robot navigation and refers to the process of generating a path or trajectory for a robot to traverse in order to cover an entire area or region of interest. The primary objective of coverage path planning is to ensure that the robot can systematically explore and survey the target environment efficiently and effectively, minimizing redundant or unnecessary movements. Several algorithms are used for coverage path planning, such as grid-based methods [

42], cell decomposition methods [

43] , Voronoi-based methods [

44], potential field methods [

45], and sampling-based methods [

46]. However, all the methods need to find the navigable area for the robot first; hence, this kind of map would be indispensable.

Energy budget calculation: Autonomous mobile robots operating alone or in fleets need to know their energy consumption before starting operations to calculate when to go to the nearest stations for manual refueling or recharge their batteries (in the case of electric vehicles). Moreover, estimating the energy budget is very important when selecting the installation location for charging stations.

Global path planning: Global path planning is a fundamental aspect of autonomous mobile robot navigation. It involves finding a high-level path from the robot’s initial position to the goal location, considering the overall environment and the robot’s capabilities. This path is typically represented as a series of waypoints, or key poses the robot must follow to reach its destination. The global path is planned before the robot starts moving, and it provides a general roadmap for the entire navigation task. The environment is usually represented as a map, either in a grid-based format or using continuous representations like occupancy grids or point clouds. The map contains information about obstacles, free spaces, and other relevant features. Various algorithms are used to compute the global path and these algorithms find the shortest or most optimal path from the starting point to the goal, considering the map’s obstacles and terrain. Global path planning may consider high-level constraints, such as avoiding specific areas (e.g., pivot ruts), considering different terrain types, or optimizing for specific criteria like energy consumption or time. Once the global path is generated, the robot follows it until it encounters local obstacles or deviations from the planned trajectory.

Obstacle avoidance: The robot could use the map to detect obstacles such as pivot ruts, large boulders/rocks, or big ditches on its path. By comparing the planned trajectory with the occupancy status of grid cells along the path, the robot can identify potential obstacles or collisions and adjust its route to avoid them. Global planning algorithms use map information to generate safe, smooth-motion trajectories that avoid obstacles/collisions.

6. Limitations And Future Work

The height of the flight was 50 meters from the ground, usually used for precision agricultural purposes. However, lower height might give better results, which has not been tested here. Therefore, there is room for optimizing height to extract the best quality row information for the map creation. We did not optimize windspeed, cloud cover conditions, temperature, etc., while taking pictures by UAV which are important for taking crisp images. We used only RGB images without any color model conversion. Other bands, like the red edge band or infrared band, might give better segmentation results for the map creation. We used a simple and straightforward way to create a binary map from orthomosaic image rather than lengthy, complex or custom-developed algorithms. Custom algorithms or machine learning techniques might give better results for occupancy grid creation from UAV imagery. But they were not tested here because we aimed to keep the process very simple and quick.

7. Conclusions

Mapping is an essential task for autonomous agricultural robots. A predefined map is helpful for global or coverage path planning. Acquiring current imagery of crop fields using satellites for map creation is either difficult or expensive whereas image gathering using UAVs is convenient and cheap. Moreover, custom cameras can be easily attached, which is impossible in satellite imagery. UAV height can be easily controlled for desired coverage or image resolution. As crop density varies from crop to crop and from time to time, updating the map several times during the growing period is required, and using UAVs is an excellent option for this task. This study shows a simple methodology with which maps can be created using UAVs and utilized for row crop navigation by UGVs. We did a small case study to show the suitability of the map creation method, and there is scope for improvement of the procedures, such as optimization of UAV’s height with map coverage, proper timing of flight operation to extract best quality row information, and robust algorithm development. This work paves the ground for map generation for autonomous navigation of agricultural robots through crop rows.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. ; methodology, H.M.; software, H.M., M.G., J.E.A; formal analysis, H.M.; investigation, H.M.; resources, H.M., M.G., J.E.A ; data curation, H.M., M.G., J.E.A; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.,M.G.; writing—review and editing, H.M.; visualization, H.M.; supervision, D.F.; project administration, D.F.; funding acquisition, D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA-USDA).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMCL |

Adaptive Monte Carlo localization |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Networks |

| CPP |

Coverage Path Planning |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier Transform |

| GIS |

Geographic Information Systems |

| GNSS |

Global Navigation Satellite Systems |

| IEEE |

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| ROS |

Robot Operating System |

| SLAM |

Simultaneous localization and mapping |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UGV |

Unmanned Ground Vehicles |

References

- Thrun, S.; Burgard, W.; Fox, D. A probabilistic approach to concurrent mapping and localization for mobile robots. Autonomous Robots 1998, 5, 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- González, D.; Pérez, J.; Milanés, V.; Nashashibi, F. A Review of Motion Planning Techniques for Automated Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2016, 17, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbers, R.; Adamchuk, V.I. Precision agriculture and food security. Science 2010, 327, 828–831, Publisher: American Association for the Advancement of Science. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Zhang, L. Detection Algorithm for Crop Multi-Centerlines Based on Machine Vision. Transactions of the ASABE 2008, 51, 1089–1097, Place: St. Joseph, MI Publisher: ASABE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.P.; Soto, I.; Eory, V.; Beck, B.; Balafoutis, A.; Sánchez, B.; Vangeyte, J.; Fountas, S.; van der Wal, T.; Gómez-Barbero, M. Exploring the adoption of precision agricultural technologies: A cross regional study of EU farmers. Land use policy 2019, 80, 163–174, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani, F.; Seyyedabbasi, A.; Nematzadeh, S.; Candan, F.; Çevik, T.; Anka, F.A.; Randazzo, G.; Lanza, S.; Muzirafuti, A. Adaptive metaheuristic-based methods for autonomous robot path planning: Sustainable agricultural applications. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 943, Publisher: Mdpi. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein, M.; Khedr, M.; El-Sheimy, N. Crop row detection procedure using low-cost UAV imagery system. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2019, 42, 349–356, Publisher: Copernicus Publications Göttingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS Journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2014, 92, 79–97, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Ludovisi, R.; Tauro, F.; Salvati, R.; Khoury, S.; Mugnozza Scarascia, G.; Harfouche, A. UAV-based thermal imaging for high-throughput field phenotyping of black poplar response to drought. Frontiers in plant science 2017, 8, 252873, Publisher: Frontiers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pádua, L.; Adão, T.; Hruška, J.; Sousa, J.J.; Peres, E.; Morais, R.; Sousa, A. Very high resolution aerial data to support multi-temporal precision agriculture information management. Procedia computer science 2017, 121, 407–414, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, G.A.; Abdala, D.D.; Escarpinati, M.C. Plantation Rows Identification by Means of Image Tiling and Hough Transform. In Proceedings of the VISIGRAPP (4: VISAPP); 2018; pp. 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Louargant, M.; Jones, G.; Faroux, R.; Paoli, J.N.; Maillot, T.; Gée, C.; Villette, S. Unsupervised classification algorithm for early weed detection in row-crops by combining spatial and spectral information. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 761, Publisher: MDPI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabatel, G.; Delenne, C.; Deshayes, M. A non-supervised approach using Gabor filters for vine-plot detection in aerial images. Computers and electronics in Agriculture 2008, 62, 159–168, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.; Qi, L. Crop-row detection algorithm based on Random Hough Transformation. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2011, 54, 1016–1020, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Vidović, I.; Cupec, R.; Hocenski, Ž. Crop row detection by global energy minimization. Pattern Recognition 2016, 55, 68–86, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delenne, C.; Durrieu, S.; Rabatel, G.; Deshayes, M. A Local Fourier Transform approach for vine plot extraction from aerial images. Object-Based Image Analysis: Spatial Concepts for Knowledge-Driven Remote Sensing Applications 2008, pp. 443–456. Publisher: Springer. Publisher: Springer.

- Delenne, C.; Durrieu, S.; Rabatel, G.; Deshayes, M.; Bailly, J.S.; Lelong, C.; Couteron, P. Textural approaches for vineyard detection and characterization using very high spatial resolution remote sensing data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2008, 29, 1153–1167, Publisher: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen, A.K.; Dyrmann, M.; Karstoft, H.; Jørgensen, R.N.; Gislum, R. Semantic segmentation of mixed crops using deep convolutional neural network. 2016.

- Bah, M.D.; Hafiane, A.; Canals, R. Deep learning with unsupervised data labeling for weed detection in line crops in UAV images. Remote sensing 2018, 10, 1690, Publisher: MDPI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osco, L.P.; De Arruda, M.d.S.; Junior, J.M.; Da Silva, N.B.; Ramos, A.P.M.; Moryia, É.A.S.; Imai, N.N.; Pereira, D.R.; Creste, J.E.; Matsubara, E.T.; et al. A convolutional neural network approach for counting and geolocating citrus-trees in UAV multispectral imagery. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2020, 160, 97–106, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Group, I.R.M.D.R.W.; et al. IEEE Standard for Robot Map Data Representations for Navigation 2015.

- Filliat, D.; Meyer, J.A. Map-based navigation in mobile robots:: I. a review of localization strategies. Cognitive systems research 2003, 4, 243–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortenkamp, D.; Bonasso, R.P.; Murphy, R. Artificial intelligence and mobile robots: Case studies of successful robot systems; MIT Press, 1998.

- Borenstein, J.; Koren, Y.; et al. The vector field histogram-fast obstacle avoidance for mobile robots. IEEE transactions on robotics and automation 1991, 7, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, M.G.; Newman, P.; Clark, S.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F.; Csorba, M. A solution to the simultaneous localization and map building (SLAM) problem. IEEE Transactions on robotics and automation 2001, 17, 229–241. [Google Scholar]

- Thrun, S. Learning metric-topological maps for indoor mobile robot navigation. Artificial intelligence 1998, 99, 21–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, B. A frontier-based approach for autonomous exploration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 1997 IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation CIRA’97.’Towards New Computational Principles for Robotics and Automation’. IEEE; 1997; pp. 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec, H.; Elfes, A. High resolution maps from wide angle sonar. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. 1985 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation. IEEE, 1985, Vol. 2, pp. 116–121.

- Li, Y.; Ruichek, Y. Occupancy grid mapping in urban environments from a moving on-board stereo-vision system. Sensors 2014, 14, 10454–10478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsadik, B.; Karam, S. The simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM)-An overview. Journal of Applied Science and Technology Trends 2021, 2, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cantelli, L.; Mangiameli, M.; Melita, C.D.; Muscato, G. UAV/UGV cooperation for surveying operations in humanitarian demining. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE international symposium on safety, security, and rescue robotics (SSRR). IEEE; 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Minaeian, S.; Liu, J.; Son, Y.J. Vision-based target detection and localization via a team of cooperative UAV and UGVs. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics: Systems 2015, 46, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Mammarella, M.; Comba, L.; Biglia, A.; Dabbene, F.; Gay, P. Cooperation of unmanned systems for agricultural applications: A theoretical framework. Biosystems Engineering 2022, 223, 61–80, Publisher: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, J.; Zenkevich, S.L.; Nazarova, A.V.; Zhai, M. Path planning based on map matching in UAV/UGV collaboration system. International Journal of Intelligent Unmanned Systems 2021, 9, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Deng, G.; Luo, C.; Lin, Q.; Yan, Q.; Ming, Z. A hybrid path planning method in unmanned air/ground vehicle (UAV/UGV) cooperative systems. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2016, 65, 9585–9596, Publisher: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Katikaridis, D.; Moysiadis, V.; Tsolakis, N.; Busato, P.; Kateris, D.; Pearson, S.; Sørensen, C.G.; Bochtis, D. UAV-supported route planning for UGVs in semi-deterministic agricultural environments. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1937, Publisher: MDPI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macenski, S.; Martín, F.; White, R.; Ginés Clavero, J. The Marathon 2: A Navigation System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Macenski, S.; Martín, F.; White, R.; Clavero, J.G. The Marathon 2: A Navigation System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2020; pp. 2718–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovino, M.; Scukins, E.; Styrud, J.; Ögren, P.; Smith, C. A survey of behavior trees in robotics and ai. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2022, 154, 104096. [Google Scholar]

- Iovino, M.; Förster, J.; Falco, P.; Chung, J.J.; Siegwart, R.; Smith, C. On the programming effort required to generate Behavior Trees and Finite State Machines for robotic applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2023; pp. 5807–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mier, G.; Valente, J.; de Bruin, S. Fields2Cover: An Open-Source Coverage Path Planning Library for Unmanned Agricultural Vehicles. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2023, 8, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Zheng, R.; Wei, J.; Guo, D.; Yang, T.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y. Path planning of mobile Robot based on improved ant colony algorithm based on Honeycomb grid. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 5th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC). IEEE, 2021, Vol. 5, pp. 1358–1362.

- Šeda, M. Roadmap methods vs. cell decomposition in robot motion planning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th WSEAS international conference on signal processing, robotics and automation. World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society (WSEAS) Athens, Greece, 2007, pp. 127–132.

- Gomez, C.; Fehr, M.; Millane, A.; Hernandez, A.C.; Nieto, J.; Barber, R.; Siegwart, R. Hybrid topological and 3d dense mapping through autonomous exploration for large indoor environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE; 2020; pp. 9673–9679. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X. Research of path planning for mobile robots based on fuzzy artificial potential field method. Control Engineering of China 2022, 29, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, L.; Koenig, S.; Arras, K.O. RRT-based nonholonomic motion planning using any-angle path biasing. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE; 2016; pp. 2775–2781. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).