1. Introduction

Compared with traditional shortwave infrared, the extended shortwave infrared (eSWIR) detector (1.7 μm-2.5 μm) has a significant advantage in terms of image quality 1. In a degraded visual environment (smoke, haze, or specific dust), the eSWIR detector can capture targets at a longer distance 2. It is widely used in military, earth sciences, satellite remote sensing, and optical communication systems 3. In addition, the eSWIR spectral imaging capability can also be utilized by NASA for planetary science, primarily to study the Earth’s surface as well as other nearby celestial bodies 4.

To better serve the application fields of eSWIR, a multitude of material systems have been studied. InGaAs based on InP substrate lattice matching is commonly used for 1.7μm detection. In order to expand the detection wavelength, InGaAs need to increase the In component, which leads to lattice mismatch. Therefore, the defects of the material will cause serious degradation of the device performance 5. HgCdTe material has good wavelength tunability and can cover the eSWIR spectral region. However, the difficulty of growing HgCdTe materials (inhomogeneity and low yield), the high cost of the CdZnTe substrate, and the complex device manufacturing process make this solution insufficient for an inexpensive eSWIR detector 6. Type-II superlattice (T2SL) materials have the advantages of strong band-gap adjustment flexibility, high carrier effective mass, and good growth uniformity in large areas 7. InGaAs/GaAsSb T2SL structures can achieve a narrower band gap than InGaAs or GaAsSb. Its lattice-matching growth on the InP substrate can greatly reduce the dislocation in epitaxy 8. R.Sidhu et al. have successfully extended the wavelength of InGaAs/GaAsSb to 2.4 μm 9, and researchers are still trying to expand the wavelength. The M structure based on the InAs/GaSb/AlSb material system has greater carrier effective mass and greater band gap tuning freedom 10. A p-i-n homogeneous focal plane array imager based on InAs/GaSb/AlSb has been proved 1.

In order to improve the performance of the device, it is necessary to suppress the dark current density to enhance the specific detectivity and responsivity of the photodetector. The characteristic of nBn architecture is that its unique electronic barrier is designed to block the dark current without hindering the photocurrent 11. Arash Dehzangi et al. combined the large bandgap electron barrier AlAs0.1Sb0.9/GaSb with InAs/GaSb/AlSb nBn structure to realize an eSWIR detector with low dark current density 12. PBn structure can also create a unipolar barrier, which can successfully block the dark current related to the depletion region. It also has the advantage of very low voltage bias dependence. Jiang et al. adopted the PBn structure to suppress the dark current of the device and improve the quantum efficiency 13. Besides, the pBin structure can also extend the device’s absorption into the visible light spectrum. It utilizes large bandgap AlAs0.1Sb0.9/GaSb materials as window layers and designs the band alignment of this heterointerface to effectively extract photogenerated carriers. Arash Dehzangi et al. demonstrated a visible/extended shortwave infrared detector based on the InAs/AlSb/GaSb T2SL 14. However, the effect of large band gap AlAs0.1Sb0.9/GaSb materials on the photoelectric performance of InAs/GaSb/AlSb T2SL eSWIR devices still lacks detailed investigation.

This paper presents an InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb T2SL eSWIR detector based on a pBin structure with a 100% cutoff wavelength of 1.9 μm. By optimizing the doping concentration of the AlAs0.1Sb0.9/GaSb barrier, the device achieves high performance specific detectivity. The experimental results are consistent with the simulation results. With the increase of the doping concentration of the barrier structure, the dark current and the responsivity of the device also increase. By separating the bulk dark current and surface dark current of the device, we determined that the optimal doping concentration of the barrier is p-type 1×1017 cm−3. The bulk detectivity of the device is maximized to 2.1×1011 cm⋅Hz1/2/W.

2. Design, Growth, and Fabrication

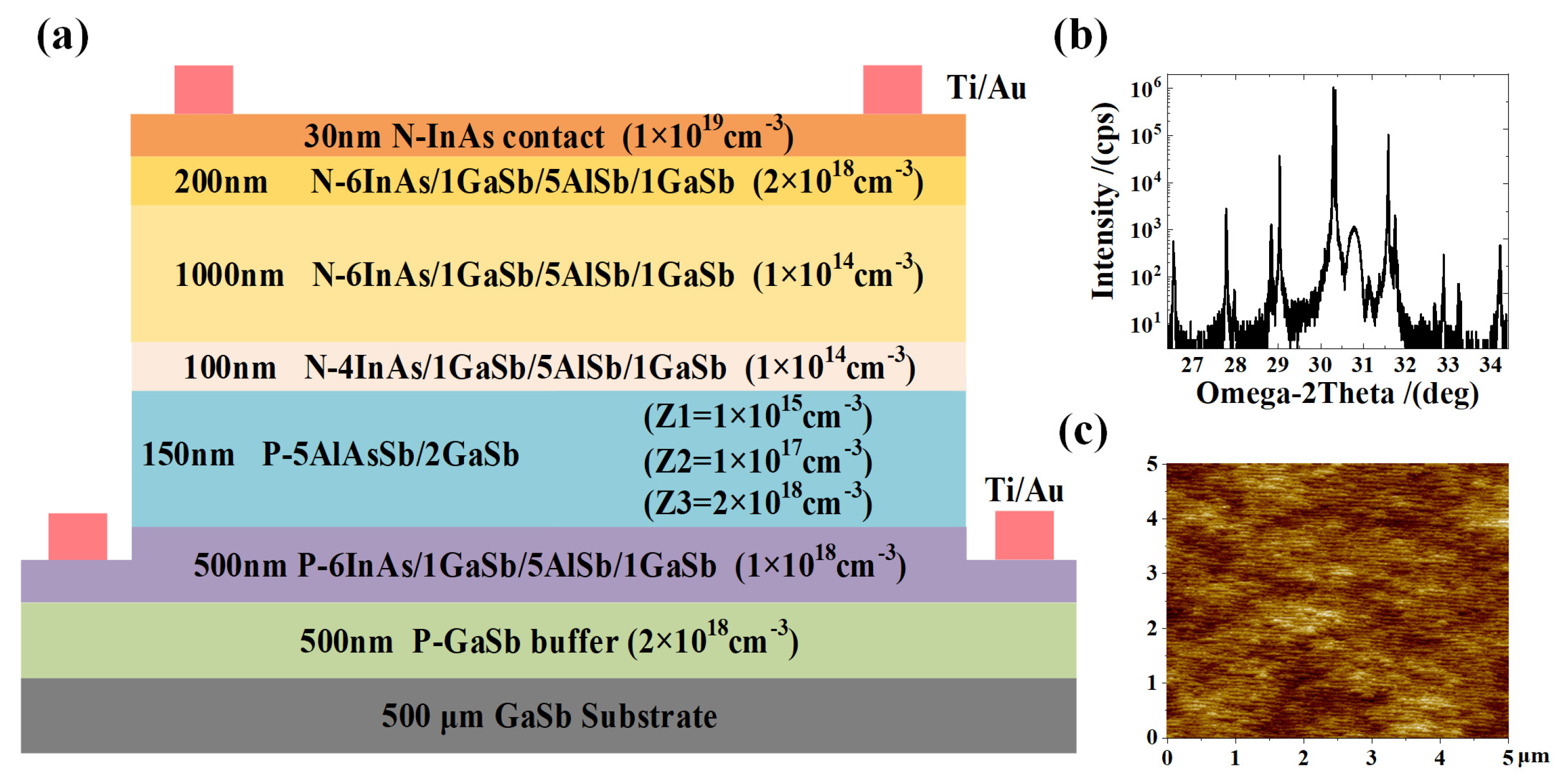

The material was grown on an n-type GaSb (001) substrate by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) system of Komponenten, Germany. As shown in

Figure 1a, it is the designed pBin type eSWIR device structure. Firstly, a 500 nm GaSb buffer layer (p-type 2×10

18 cm

−3) was epitaxially grown on the GaSb substrate. Then, the bottom contact layer is 500 nm 6/1/5/1 mono–layers (MLs) of InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb (p-type 10

18 cm

−3). The second electron barrier layer is 150 nm 5/2 MLs of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb. Due to the difference in the valence band position between the barrier and the absorption region material, the valence band position of the barrier is adjusted by intentional doping. During the experiment, different beryllium (Be) doping source temperatures were used to achieve precise control of the material doping concentration. The doping concentration values corresponding to the temperature of the Be source are precisely calibrated by means of the Hall test. The doping concentrations of Z1, Z2, and Z3 were 1×10

15 cm

-3, 1×10

17 cm

-3, and 2×10

18 cm

-3, respectively. Subsequently, the first electron barrier layer is 100 nm 4/1/5/1 MLs of InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb (undoped, n-type 10

14 cm

-3). The absorption region is 1000 nm 6/1/5/1 MLs of InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb (undoped, n-type 10

14 cm

-3) T2SL material. The top contact layer is 200 nm 6/1/5/1 MLs of InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb (n-type 2×10

18 cm

-3), and the last 30 nm InAs (n-type 10

19 cm

-3) serves as the cap layer of the device.

Figure 1b,c are high-resolution X-ray diffraction (HRXRD) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of sample Z2, respectively. The HRXRD satellite peak results show that the periodic thicknesses of the absorption region, first barrier region, and second barrier region are approximately 3.85nm, 3.37nm, and 2.07nm, respectively. The stress mismatch between the above superlattice materials and GaSb is within 0.1%, which is consistent with the superlattice design. AFM displays clear atomic steps on the surface of the material, with a Root Mean Square (RMS) roughness of only 0.125nm in the 5×5 μm

2 region. The surface quality of the material is high. Samples Z1 and Z3 have similar lattice quality and surface quality.

The three devices were prepared using the same batch device manufacturing process. The circular mesa was wet-etched with C6H8O7:H3PO4:H2O2:H2O (5 g:2 mL:1 mL:20 mL) solution. The solution has an etching rate of about 150 nm/min and can precisely control the etching depth to the p-type bottom contact layer. These devices have not been passivated. Finally, Ti/Au (10 nm/100 nm) was deposited on the InAs cap layer (n-type) and bottom contact (p-type) using electron beam evaporation for metallization.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Result

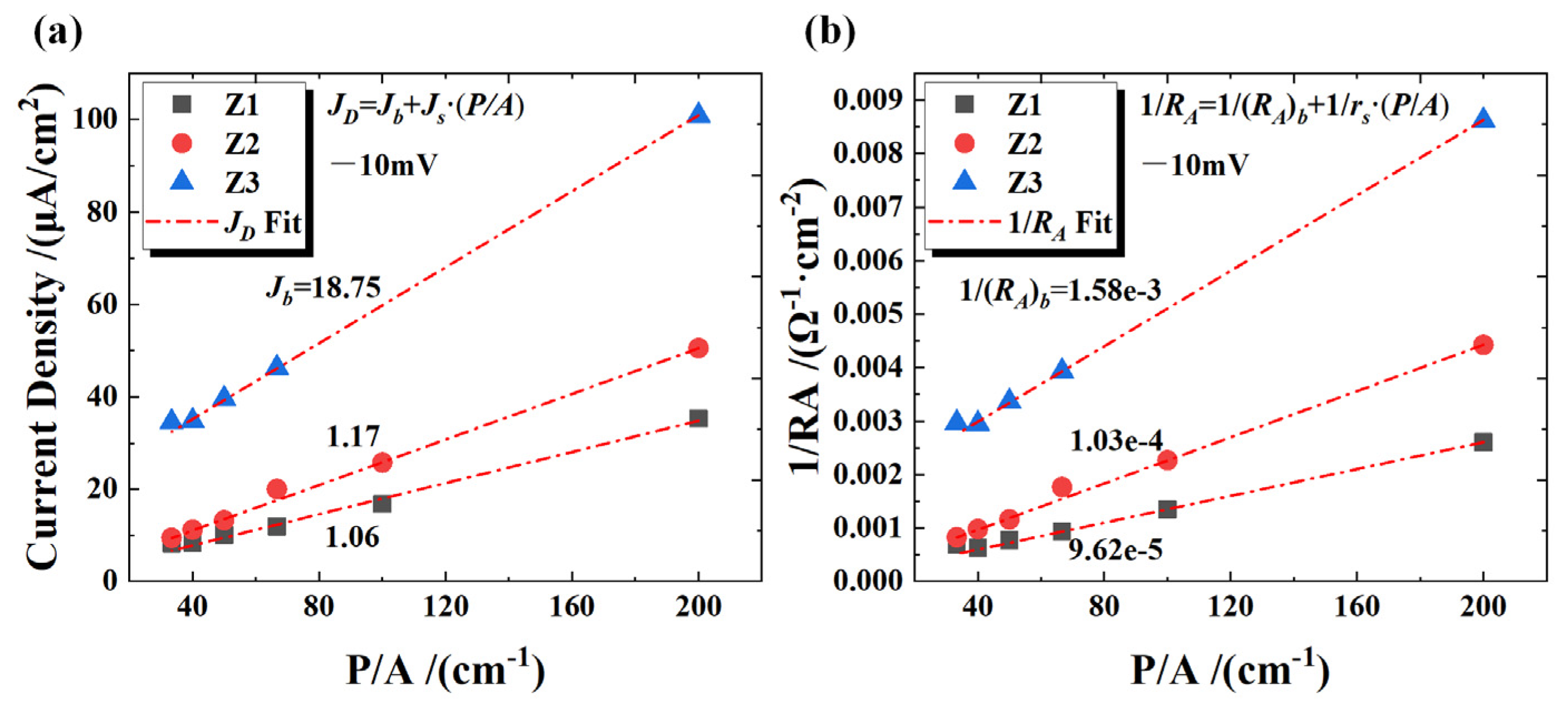

To verify the electrical performance of different devices at 300K, the current and voltage characteristics of devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 were measured. The experiment used a semiconductor analyzer (B1500A) as the voltage source and applied a bias voltage to the device through the probe arm of a low-temperature probe station (CRX-VF). The total dark current of the device includes bulk dark current and surface dark current. In order to investigate the effect of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb barrier on the dark currents of devices Z1, Z2, and Z3, it is necessary to separate the surface dark currents of devices. Therefore, the current-voltage characteristic curves of devices with different sizes are tested. The bulk current density (

Jb) and surface dark current density (

Js) of the device can be separated by the following Equation (15):

where

JD is the total dark current density of the device, P is the mesa perimeter, and A is the mesa area of the device. As shown in

Figure 2a, the

JD (at -10 mV) of devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 were extracted. The

JD of device Z1 is the smallest and the

JD of device Z3 is the largest. Subsequently, Equation (1) was used to fit the

JD of different devices. The fitting results show that the

Jd of the devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 are 1.06×10

-6 A/cm

2, 1.17×10

-6 A/cm

2, and 1.875×10

-5 A/cm

2, respectively. Besides,

JD is also showing an increasing trend. The bulk differential resistance area (

RA)

b of the device is separated in the same way for the bulk detectivity calculation of the device. The fit uses the following Equation (16):

where

RA is the total differential resistance area of the device and

rs is the surface resistivity of the device. The fitting results showed that the 1/(

RA)

b of the devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 were 9.62×10

-5 Ω

-1·cm

-2, 1.03×10

-4 Ω

-1·cm

-2, and 1.58×10

-3 Ω

-1·cm

-2, respectively. The (

RA)

b of the device shows a decreasing trend as the doping concentration of the AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb barrier increases.

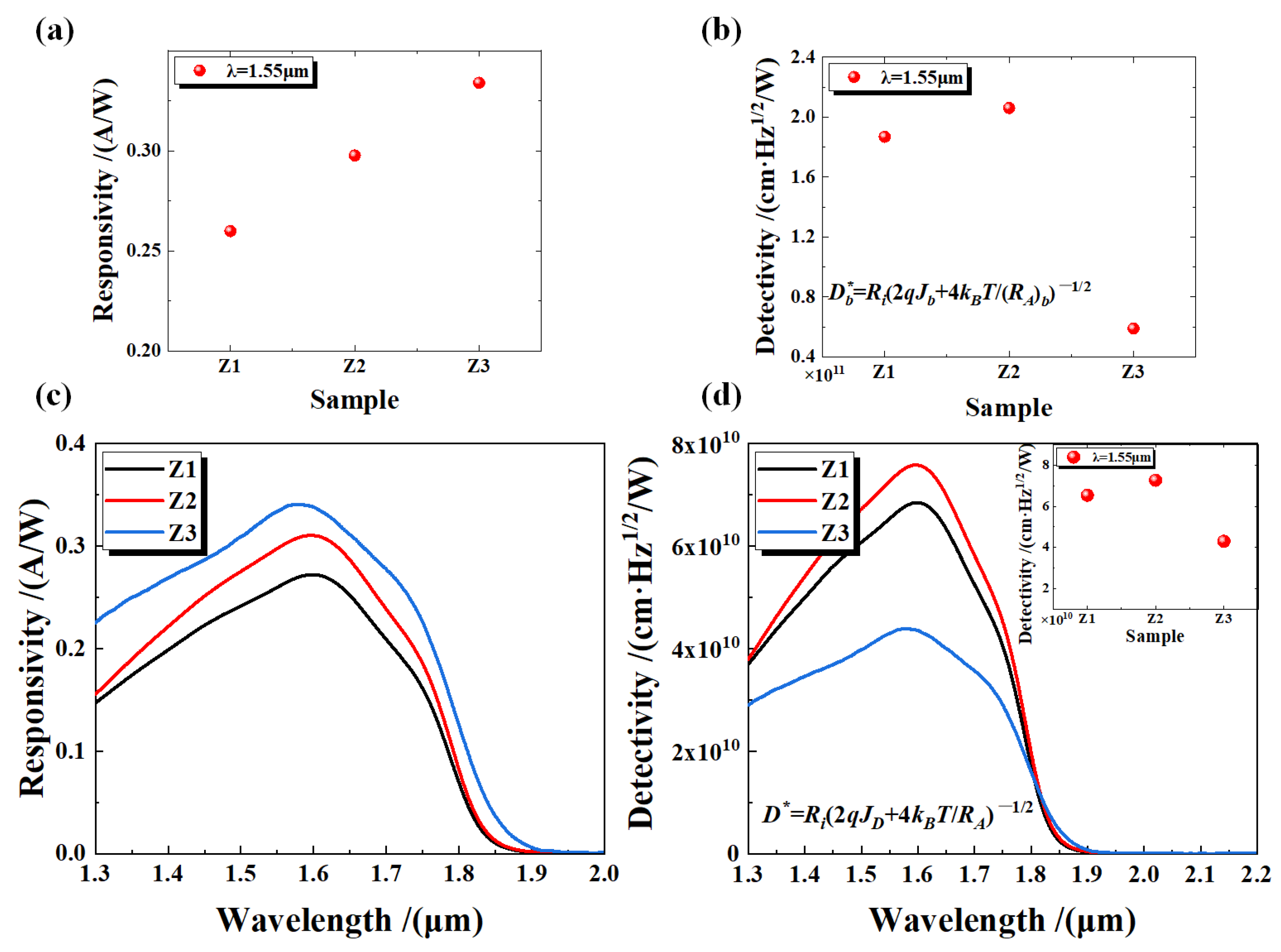

To verify whether there are differences in the optical properties of different devices under the condition of 300K, we conducted spectral response tests on devices Z1, Z2, and Z3. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Bruker FTIR VERTEX 80/80v) was used to measure the spectral response of the device. By setting the sensitivity of the current amplifier (SR570) to 200 μA/V, the optical signal received by the device is amplified, and then the spectral information is obtained through the digital-to-analog converter. Finally, the device responsivity is measured using a calibrated 1273K blackbody source. As shown in

Figure 3a, the responsivity of the devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 at a wavelength of 1.55 μm is 0.26 A/W, 0.30 A/W, and 0.33 A/W, respectively. Furthermore, the spectral response test results show that the 100% cutoff wavelength of all three devices is about 1.9 μm. Then, the spectral response curves are normalized by using the responsivity at 1.55 μm to obtain the responsivity across the full wavelength range (

Figure 3c). Therefore, the device responsivity increases with the increase of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb doping concentration. This phenomenon shows the same variation trend as the

Jd of the device. Although the device Z3 has a high responsivity, it also has a large

Jd. To further evaluate the comprehensive performance of devices Z1, Z2, and Z3, we neglected the

Js component of the devices and calculated their bulk detectivity

using

Jd and (

RA)

b. The calculation formula is as follows:

where

Ri is the device responsivity, q is the fundamental charge,

kB is the Boltzmann constant, and

T is the device operating temperature (at 300K).

Figure 3b shows that the

of devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 are 1.8 × 10

11 cm·Hz

1/2/W, 2.1 × 10

11 cm·Hz

1/2/W, and 5.9 × 10

10 cm·Hz

1/2/W, respectively. The

of the device shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. Device Z2 exhibits the best comprehensive performance and has an improvement of 256% compared to device Z3. In addition, we also calculated the specific detectivity

17,18 of devices Z1, Z2, and Z3 (with a diameter of 1200 μm) under full spectrum. As shown in

Figure 3d, device Z2 has the highest specific detectivity (its dark current density is 9.48×10⁻⁶ A/cm² at a bias of -10 mV), and the peak specific detectivity is 7.59×10¹⁰ cm·Hz¹/²/W at 1.6 μm. Device Z2 has improved by approximately 73% compared to device Z3.

Table 1 shows the performance comparison between device Z2 and other eSWIR detectors. The specific detectivity of our device has certain advantages compared to other detectors.

3.2. Simulation and Discussion

Aiming at the problem that the doping concentration of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb changes the current of the device, we use simulation tools to further explain the experimental results. In this study, the performance of semiconductor devices was numerically simulated using Technology Computer Aided Design (TCAD) models 20, including mobility models (parallel electric field-dependent model), recombination models (Shockley-Read-Hall recombination model, Auger recombination model, and optical recombination model), and carrier statistics models (Fermi-Dirac statistics model). The properties of superlattice materials were calculated by weighted average of InAs, GaSb, AlSb and AlAs compounds 21. These include conduction band density (

Nc), valence band density (

Nv), electron mobility (mun), hole mobility (mup), and dielectric constant. Moreover, the bandgap energy of superlattice materials is calculated using the 8kp model 22.

Table 2 shows the partial parameter values (at 300K) of 6/1/5/1 MLs of InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb, 4/1/5/1 MLs of InAs/GaSb/AlSb/GaSb, and 5/2 MLs of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb superlattice materials. The model was solved by Newton and Gummel combinatorial iterative method.

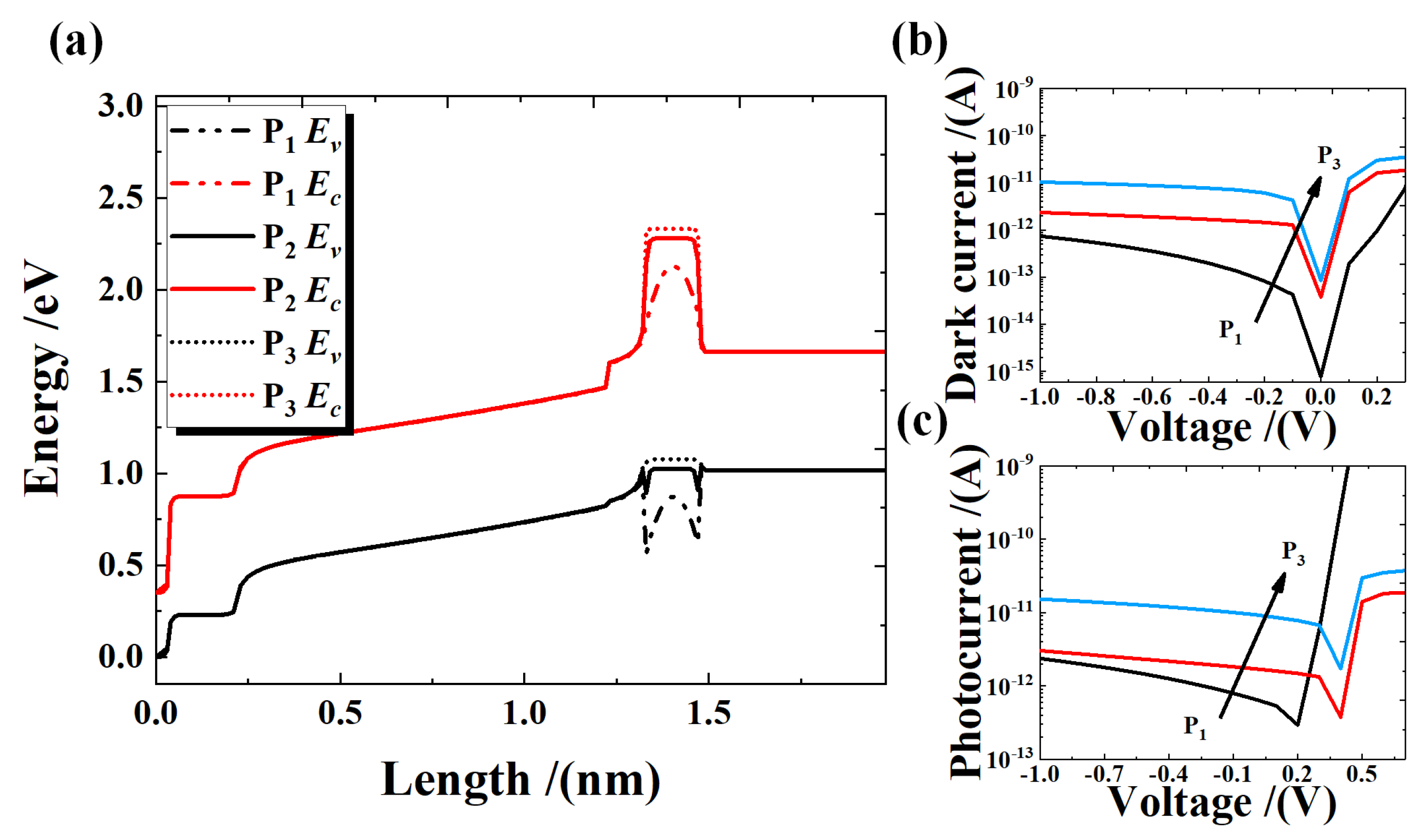

We simulated the effects of AlAs₀.₁Sb₀.₉/GaSb with varying doping concentrations on the optoelectronic performance of the devices. The InAs material at the top of the device is taken as the origin, and the opposite direction of material epitaxy is taken as the positive direction to establish the coordinate system. The conduction and valence bands of the material (at -10 mV) are shown in

Figure 4a. This includes a 30 nm InAs cap layer (n-type 1×10¹⁹ cm⁻³), a 200 nm top contact layer (n-type 2×10¹⁸ cm⁻³) serving as a photogenerated hole carrier extractor, a 1000 nm absorption region (unintentionally doped, n-type 1×10¹⁴ cm⁻³) for generating photogenerated carriers, a 100 nm first electron barrier region (unintentionally doped, n-type 1×10¹⁴ cm⁻³), a 150 nm second electron barrier region (p-type: P

1 = 1×10¹⁵ cm⁻³, P

2 = 1×10¹⁷ cm⁻³, P

3 = 2×10¹⁸ cm⁻³), and a 500 nm bottom contact layer (p-type 1×10¹⁸ cm⁻³) acting as a photogenerated electron extractor.

Figure 4a shows that the first and second electron barriers with a wide band gap in the device structure can reduce the partial generation-recombination dark current. The second electron barrier can also block the passage of thermally excited electrons 4. The valence band maximum energy

Ev and the conduction band minimum energy

Ec both shift up as the doping concentration of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb increases.

Figure 4b shows the simulation data of dark current under different bias voltages. The results indicate that the dark current of the device increases with the rising p-type doping concentration in AlAs₀.₁Sb₀.₉/GaSb. This may be caused by the high hole concentration of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb. Under thermal excitation, holes pass through the first electron barrier region to reach the top contact layer, resulting in a larger dark current. Besides, at the illumination of 1.55μm, we can simulate the photocurrent data in

Figure 4c. Under -10 mV bias, the photocurrent increases with the increase of AlAs

0.1Sb

0.9/GaSb doping concentration. In the absorption region, photogenerated carriers (holes and electrons) are generated under optical excitation, with the top contact layer extracting electrons and the bottom contact layer extracting holes. Due to the upward shift of the

Ev in the AlAs₀.₁Sb₀.₉/GaSb barrier, the photocurrent increases as the bottom contact layer extracts more photogenerated hole carriers. Therefore, the simulation data demonstrate that the variation trends of photocurrent and dark current align with the experimental data.

4. Conclusion

In summary, an InAs/GaSb/AlSb T2SL photodetector based on the optimization of the AlAs0.1Sb0.9/GaSb barrier has been designed. Both experimental and simulated studies employed device structures with three different p-type doping concentrations in the AlAs₀.₁Sb₀.₉/GaSb barrier. The results consistently demonstrate that the current increases with elevated p-type doping concentrations in the barrier. Therefore, we evaluated the device performance by comparing bulk detectivity . The optimized eSWIR detector achieved a peak specific detectivity D∗ of 7.59×1010 cm·Hz1/2/W at 1.6 μm, representing a ~73% improvement. Additionally, the detector exhibits a 100% cutoff wavelength of 1.9 μm at 300 K, with a dark current density of 9.48×10−6 A/cm2 under a -10 mV bias. This work provides a design strategy for advanced eSWIR device architectures and enables the fabrication of high-performance eSWIR imagers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z., L.L., Y.F. and J.O.; methodology, J.Y.; software, W.C.; validation, J.Y., L.L. and W.C.; formal analysis, L.Z., Y.F. and J.O.; investigation, L.L.; resources, L.Z., Y.F. and J.O.; data curation, J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.Y., L.L., and W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Sub project (2022YFF0705801); National Natural Science Foundation of China (62205029); Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (2022QNRC001).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hoang, A. M.; Chen, G.; Haddadi, A.; Abdollahi Pour, S.; Razeghi, M., Demonstration of shortwavelength infrared photodiodes based on type-II InAs/GaSb/AlSb superlattices. Applied Physics Letters, 2012, 100 (21), 211101. [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, W.; Joshua, F.; Patrick, L.; Orges, F.; Rich, P.; David, B.; Ronald, D. In Target discrimination in the extended SWIR (eSWIR) band (2-2.5µm) compared to Vis, NIR, and SWIR in degraded visual environments, Proc.SPIE, 2022; p 1210606. 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.-c., NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sensing of Environment 1996, 58 (3), 257-266. [CrossRef]

- Dehzangi, A.; McClintock, R.; Haddadi, A.; Wu, D.; Chevallier, R.; Razeghi, M., Type–II superlattices base visible/extended short–wavelength infrared photodetectors with a bandstructure–engineered photo–generated carrier extractor. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9 (1), 5003. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Y.; Oguz, F.; Besikci, C., Extended wavelength SWIR InGaAs focal plane array: Characteristics and limitations. Infrared Physics & Technology, 2015, 70, 134-137. [CrossRef]

- Tennant, W. E.; Cockrum, C. A.; Gilpin, J. B.; Kinch, M. A.; Reine, M. B.; Ruth, R. P., Key issues in HgCdTe-based focal plane arrays: An industry perspective. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures Processing, Measurement, and Phenomena, 1992, 10 (4), 1359-1369. [CrossRef]

- Piquini, P.; Zunger, A.; Magri, R., Pseudopotential calculations of band gaps and band edges of short-period (InAs)n/(GaSb)m superlattices with different substrates, layer orientations, and interfacial bonds. Physical Review B, 2008, 77 (11), 115314. [CrossRef]

- Easley, J.; Martin, C. R.; Ettenberg, M. H.; Phillips, J., InGaAs/GaAsSb Type-II Superlattices for Short-Wavelength Infrared Detection. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2019, 48 (10), 6025-6029. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.; Ning, D.; Campbell, J. C.; Holmes, A. L., A long-wavelength photodiode on InP using lattice-matched GaInAs-GaAsSb type-II quantum wells. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, 2005, 17 (12), 2715-2717. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B. M.; Razeghi, M.; Nathan, V.; Gail, J. B. In Type-II M structure photodiodes: an alternative material design for mid-wave to long wavelength infrared regimes, Proc. SPIE, 2007, 6479, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.-M.; Hoffman, D.; Delaunay, P.-Y.; Razeghi, M., Dark current suppression in type II InAs∕GaSb superlattice long wavelength infrared photodiodes with M-structure barrier. Applied Physics Letters, 2007, 91 (16), 163511. [CrossRef]

- Dehzangi, A.; Haddadi, A.; Chevallier, R.; Zhang, Y.; Razeghi, M., nBn extended short-wavelength infrared focal plane array. Opt. Lett., 2018, 43 (3), 591-594. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chang, F.; Zhou, W.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; Jiang, D.; Hao, H.; Wang, G.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; Niu, Z.-C., High-performance extended short-wavelength infrared PBn photodetectors based on InAs/GaSb/AlSb superlattices. Chinese Physics B, 2023, 32 (3), 038503. [CrossRef]

- Dehzangi, A.; Haddadi, A.; Chevallier, R.; Zhang, Y.; Razeghi, M., Fabrication of 12 µm pixel-pitch 1280 × 1024 extended short wavelength infrared focal plane array using heterojunction type-II superlattice-based photodetectors. Semiconductor Science and Technology, 2019, 34 (3), 03LT01. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. C., Recent Advances in Avalanche Photodiodes. Journal of Lightwave Technology, 2016, 34 (2), 278-285. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lu, L.; Yu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, W.; Feng, Y.; Ren, G.; Zhu, L., Low dark current density extended short-wavelength infrared superlattice photodetector with atomic layer deposited Al2O3 passivation. Appl. Opt., 2023, 62 (30), 7960-7965. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Sun, J.; Jia, Q.; Song, Y.; Jiang, D.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y.; Niu, Z., High performance nBn detectors based on InGaAsSb bulk materials for short wavelength infrared detection. AIP Advances, 2019, 9 (10), 105106. [CrossRef]

- Mark, D. N.; Jerris, F. J.; Terrence, S. L., General noise processes in hybrid infrared focal plane arrays. Optical Engineering, 1991, 30 (11), 1682-1700. doi:doi.org/10.1117/12.55996.

- Xie, R.; Shan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yao, L.; Su, X.; Wu, D.; Hao, H.; Jiang, D.; Wang, G.; Xu, Y.; Ni, H.; Niu, Z., Extended Short-Wave Infrared Barrier Structure Focal Plane Array Based on InGaAs/GaAsSb Type-II Superlattices. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2024, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Maiti, C. K., Introducing Technology Computer-Aided Design (TCAD): Fundamentals, Simulations, and Applications. Jenny Stanford Publishing: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jones. AlxIn1-xAsySb1-y Digital Alloy Avalanche Photodiodes for Low-Noise Applications. University of Virginia, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhu, L.; Lu, L.; Chen, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Fu, Y.; Ou, J. Interface Engineering and Electron-Hole Wave Function Overlap of InAs/AlSb Superlattice Infrared Detectors. Photonics, 2023, 10 (11), 1268. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).